Abstract

The Visceral Obesity Index (VAI) is utilized as a metric employed to assess the distribution of abdominal adipose tissue as well as the functional status of adipose tissue. Nevertheless, the interplay between VAI and persistent pain has yet to be investigated. This cross-sectional analysis investigated the relationship between VAI and persistent pain among 1357 American adults from NHANES data. A logarithmic transformation of VAI was performed to adjust for skewness. Following the adjustment for relevant variables, logistic regression analysis showed a noteworthy association between VAI and chronic pain, suggesting that higher VAI values may be linked to an increased prevalence of persistent pain. Curve fitting analysis revealed a nonlinear correlation, with a breakpoint at a VAI value of 0.18. For VAI values below this threshold, each unit increase was notably correlated with an elevated prevalence of persistent pain, while increases in VAI beyond this threshold did not show a significant impact on chronic pain prevalence. Subgroup analyses indicated that the VAI may serve as a relatively independent risk factor for persistent pain. These findings highlight the possibility of incorporating abdominal adipose modification into pain management approaches and emphasize the critical importance of monitoring visceral fat accumulation to better identify patients more susceptible to chronic pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic pain, generally characterized as pain lasting or recurring for more than three months, is characterized by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as an unpleasant sensory and emotional phenomenon connected to both actual and potential tissue damage. It is classified within the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) as either primary or secondary chronic pain1,2. Due to its prolonged duration and complex pathogenesis, Chronic pain is frequently considered a pathological condition in its own right. Patients with chronic pain frequently adjust their expectations from eliminating pain to managing it, aiming for functional and emotional recovery. Research indicates that one in five adults worldwide suffer from moderate to severe persistent pain, significantly impacting their social and professional life quality and placing a substantial strain on medical systems3,4,5. Consequently, early symptom detection and timely intervention are essential strategies to enable the accurate diagnosis and effective management of persistent pain.

The incidence of obesity on a global scale has risen markedly in recent years, posing an increasing public health challenge. Obesity, distinguished by an atypical or excessive accumulation of fat in adipose tissue, is commonly assessed using the Body Mass Index (BMI), established based on a person’s weight and height measurements6,7. Extensive evidence supports a co-occurrence of obesity and pain, with body fat distribution emerging as a critical factor in chronic pain development8,9,10,11. However, BMI as a measure of obesity has limitations, as its relationship with body fat percentage is nonlinear and varies by gender. Additionally, BMI fails to consider the heterogeneity in fat distribution, particularly the specific health risks associated with visceral fat12,13. Obesity is commonly associated with inflammation of adipose tissue, with visceral fat playing a central role. Severe visceral obesity is frequently linked to low-grade systemic inflammation14. Furthermore, research has identified inflammation of both the peripheral nervous system and central nervous system as key contributors to the pathogenesis of chronic pain15. To address these limitations, Amato et al. created the VAI as an indirect measure of visceral adiposity and overall obesity, thereby reflecting an individual’s metabolic health status16. Earlier studies have demonstrated that VAI is linked to diabetes, high blood pressure, stroke, sarcopenia, atherosclerosis, and vascular calcification17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Nevertheless, the interaction between VAI and chronic pain has yet to be analyzed.

This research, therefore, strives to examine the connection between VAI and persistent pain in adult participants of the 1999–2004 NHANES and to assess VAI as a novel indicator for risk assessment and preliminary diagnosis in individuals with chronic pain.

Methods

Survey description

The authors utilized data from the NHANES, a national population-based cross-sectional study carried out by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) to analyze health and nutrition trends throughout the United States25. NHANES employs a complex, multistage stratified probability sampling method on a biennial cycle to obtain a representative sample of the U.S. population. The NCHS Research Ethics Review Board approved all study protocols, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant or, for those under 16, from a parent or legal guardian. Comprehensive details regarding the NHANES study design and publicly accessible data are available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/. This cross-sectional study was conducted in compliance with the STROBE reporting guidelines26.

Study population

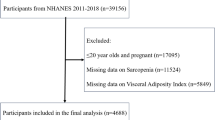

This study utilized data collected during the 1999–2004 cycle of NHANES. Initially, 3,312 participants were recruited for the cohort. Exclusion criteria applied to the following groups: 15,754 participants younger than 20 years, 11,754 individuals who had missing chronic pain data, 2,092 individuals lacking complete data for VAI calculation, and 129 individuals with missing covariate data. After applying these criteria, A sum of 1,357 qualified individuals aged 20 years and above were incorporated into the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Definition of visceral adiposity index and chronic pain

The VAI is a sex-specific measure derived from anthropometric measurements—waist circumference (WC) and BMI—and metabolic parameters—triglycerides (TG) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C)—used to estimate visceral fat levels. VAI was calculated for each participant using the formulas outlined below: for men, VAI = WC / (39.68 + (1.88 * BMI)) * (1.31 / HDL-C) * (TG / 1.03); for women, VAI = WC / (36.58 + (1.89 * BMI)) * (1.52 / HDL-C) * (TG / 0.81) (14). In this study, VAI was treated as a continuous variable, and participants were divided into quartiles based on their VAI values.

Chronic pain is described as pain that persists or reoccurs for a duration exceeding three months27. The identification of patients with persistent pain was conducted using the Miscellaneous Pain Questionnaire (MPQ110). Persistent pain encompasses a broad spectrum of types, including mechanical, musculoskeletal, inflammatory, neoplastic, and neuropathic pain. The pain may affect various anatomical regions, including, but not limited to, the limbs, trunk, head, neck, and face. Participants who indicated a pain duration of “less than one month” or “at least one month but less than three months” were categorized as not experiencing chronic pain. In contrast, those reporting durations of “at least three months but less than one year” or “more than one year” were classified as having chronic pain. Responses marked as “I don’t know” or left unanswered were regarded as missing data.

In this study, VAI was designated as the exposure variable, with chronic pain serving as the outcome variable.

Selection of covariates

This Research included various covariates that could shape the interaction between the VAI and chronic pain, encompassing sociodemographic variables such as age, gender, racial or ethnic background, educational attainment, marital status, household income, lifestyle factors (alcohol consumption and smoking status), and coexisting conditions, including coronary heart disease, heart failure, stroke, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. Race and ethnicity were categorized as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Mexican American, or belonging to another racial group. Education levels were grouped as below 9th grade, 9th to 12th grade, and 12th grade or higher. Household income was categorized by the poverty-to-income ratio (PIR): high (PIR > 3.5), moderate (PIR > 1.3 and ≤ 3.5), and low (PIR ≤ 1.3). Marital status was categorized as married, living independently, or cohabiting with a partner. Smoking status is distinguished between never-smokers, who have smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in life, and smokers, who have smoked at least 100 cigarettes in life. Never drinkers, are defined as those consuming fewer than 12 drinks per year, and drinkers, are defined as those consuming more than 12 drinks per year. BMI was calculated using an individual’s weight and height measurements… Hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, stroke, and heart failure were determined through participants’ self-reported physician diagnoses in the questionnaire. Detailed descriptions of measurement procedures for these variables can be found on the publicly accessible website www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were reported in terms of percentages, whereas continuous variables were summarized using the mean and standard deviation (SD) for data that followed a normal distribution. In contrast, for non-normally distributed data, the median and interquartile range (IQR) were utilized, following NHANES analytical guidelines. The VAI was assessed as both a continuous and categorical variable using IQR to categorize the data. T-tests assessed differences in VAI among groups experiencing chronic pain compared to those without chronic pain. For group comparisons, Chi-square tests were applied to analyze categorical variables, while one-way ANOVA was utilized for continuous variables that were normally distributed. For continuous data that exhibited skewness, the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed. Logistic regression models were constructed to Delve into the interaction between VAI and chronic pain. Model 1 was unadjusted for covariates, while Model 2 accounted for age, sex, and race. Model 3 included further adjustments for additional variables such as marital status, education level, poverty income ratio (PIR), smoking habits, alcohol consumption, as well as medical conditions like hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, and heart failure. Smoothed curve fitting was employed to explore possible nonlinear associations between VAI and persistent pain. Subgroup analyses were conducted to examine the interaction between VAI and chronic pain prevalence within each subgroup, adjusting for all other covariates to isolate particular effects on the VAI-chronic pain relationship. Interaction tests were additionally performed to evaluate the stability of associations across different subgroups. We conducted a further evaluation of the ability of VAI and BMI to detect chronic pain by utilizing ROC analysis and examining the corresponding AUC values. All analyses were conducted using the NHANES-recommended stratification and weighting scheme, with R (version 4.2) and Python (version 3.10.4)28.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

A sum of 1,357 participants from the NHANES (1999–2004) cohort was incorporated into this analysis, comprising 45.62% males and 52.38% females, with a mean age of 49.54 years (± 16.95). The Visceral Adiposity Index (VAI) was divided into quartiles, with ranges of 0.27–1.19 (≤ 1.19) for Quartile 1, 1.19–2.02 (≤ 2.02) for Quartile 2, 2.02–3.37 (≤ 3.37) for Quartile 3, and 3.37–69.67 (≤ 69.67) for Quartile 4. Among the participants, 816(60.13%) reported experiencing chronic pain, with a significant trend showing higher rates of chronic pain across increasing VAI quartiles (P = 0.002). Significant variations in age, race, education, marital status, household income, smoking and drinking habits, and prevalence of diabetes and hypertension were observed across VAI quartiles (P < 0.05). Individuals in the higher quartiles of VAI were generally older, had lower income, were more likely to be married, had a history of smoking, were less educated, and exhibited higher rates of hypertension and diabetes in comparison with those in the lowest quartile of VAI. Interestingly, alcohol consumption was associated with lower VAI scores (P < 0.05). However, no statistically significant differences were found among the VAI quartiles regarding gender, heart failure, stroke, or coronary heart disease. (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Visceral adiposity index and chronic pain

To address the asymmetry in the VAI data, a logarithmic transformation was utilized for the VAI variable. Logistic regression analysis was then performed to examine the link between the transformed VAI (Log VAI) and the incidence of chronic pain. Table 2 presents these findings, indicating that elevated Log VAI values are related to an elevated risk of chronic pain. In the unadjusted analysis, a notable positive association was observed between chronic pain incidence and Log VAI (Model 1: OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.05–2.18). Following incremental adjustment for various confounding variables, The Completely adjusted model still indicated a statistically meaningful positive relationship between Log VAI and a higher incidence of chronic pain (Model 3: OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.05–2.18). To further assess this relationship, Log VAI was divided into quartiles. Elevated quartiles of Log VAI were strongly associated with increased chronic pain incidence (p-trend = 0.004), relative to the lowest quartile. This trend remained robust even after controlling for all covariates, with the highest Log VAI quartile showing a significant positive association with persistent pain incidence (OR 1.50, 95%CI 1.08–2.07; p for trend = 0.033), thereby underscoring a robust positive link between Log VAI and persistent pain.

Nonlinear relationship and threshold effect analysis

Using smoothed curve fitting and analysis of threshold effects, we observed a possible nonlinear interaction. Between Log VAI and chronic pain, exhibiting a reversed L-shaped positive relationship (Fig. 2). Table 3 summarizes the analysis of the threshold effect, revealing an inflection point of 0.18 for Log VAI. According to logistic regression analysis, a rise in Log VAI was significantly linked to a higher incidence of chronic pain when Log VAI was below 0.18 (OR 4.78, 95% CI 1.82–12.60). However, when Log VAI exceeded 0.18, this association was no longer statistically meaningful (P = 0.729).

Subgroup analysis

We conducted subgroup analyses and interaction tests considering demographic and lifestyle factors to assess the consistency of the correlation between Log VAI and chronic pain to identify any potential variations across demographic groups (Fig. 3). The link between Log VAI and persistent pain was positive across most subgroups, except among individuals with diabetes, non-drinkers, and participants with lower education levels. This finding reinforces the function of Log VAI as a robust independent risk determinant for chronic pain. Interaction tests indicated no meaningful interactions between Log VAI and gender, education, marital status, age, race, household income, smoking, hypertension, or diabetes (P > 0.05), except for drinking status (P = 0.034).

Comparison of VAI and BMI in predicting chronic pain

We assessed the predictive ability of VAI and BMI concerning the likelihood of chronic pain by calculating the area under the curve (AUC). The results of the ROC analysis are presented in Fig. 4. The ROC analysis revealed that VAI (AUC = 0.626) outperformed BMI (AUC = 0.607) in predicting the risk of chronic pain.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study encompassing a diverse population of US adults, the author identified a notable link between VAI and chronic pain. Elevated VAI levels were consistently linked to a greater prevalence of chronic pain across different demographic groups. When VAI was analyzed as a categorized variable, the prevalence of chronic pain was notably greater in the highest quartile (quartile 4) in comparison to the lowest quartile (quartile 1). Smoothed curve fitting and threshold effect analyses further demonstrated an inverted L-shaped relationship between VAI and persistent pain prevalence, with an observed saturation effect at VAI values above 0.18, where the association ceased to be statistically significant (P = 0.729). The subgroup analyses provided a deeper exploration of the relationship between VAI and chronic pain within diverse population groups. Generally, the findings demonstrated that the direction of this relationship in the subgroups aligned with that observed in the overall study population. Nevertheless, notable deviations were identified among individuals with diabetes, non-drinkers, and those with lower educational attainment. There are multiple factors that may contribute to this observed phenomenon. One possible explanation is that individuals with lower educational attainment might be more prone to engaging in manual labor and may exhibit a higher threshold for pain perception. Additionally, those with limited education often have lower health awareness, which can result in inadequate disease screening and delayed diagnoses. Moreover, it is important to acknowledge that the relatively small sample size of the diabetic population could impact the reliability of these findings, necessitating further investigation to better understand this phenomenon in subsequent studies. It is worth noting that the interaction tests revealed no significant associations between Log VAI and variables such as gender, education level, marital status, age, race, income, smoking habits, hypertension, or diabetes. However, drinking status emerged as an exception, showing a significant interaction. These findings indicate that adopting a healthy lifestyle may effectively decrease the prevalence of chronic pain. Furthermore, to investigate the predictive capability of VAI for chronic pain, we conducted a ROC analysis. The findings revealed that VAI demonstrated superior predictive performance for chronic pain compared to BMI.

Our findings highlight the clinical significance of VAI as a potential risk predictor for persistent pain, enhancing the theoretical understanding of the relationship between visceral adiposity and pain. This provides a foundation for prospective longitudinal studies and offers insights for future treatment strategies. To the best of our understanding, this study is the first to explore the relationship between VAI and chronic pain directly. Preceding studies have established an interrelationship between obesity and persistent pain, often highlighting obesity as a predictor of persistent joint and musculoskeletal pain29,30. However, the limitations of BMI in assessing visceral adiposity often result in paradoxical findings, where some studies fail to demonstrate a straightforward relationship between obesity and pain31,32. Recent studies have demonstrated that VAI offers an advantage over BMI in evaluating obesity and its associated health risks33,34,35. Previous studies have found that obese adults experience an increased prevalence and intensity of pain symptoms, with morbidly obese individuals being four times more susceptible to experiencing persistent pain than their non-obese counterparts36,37. Community-based studies also report strong associations between obesity and various types of pain, such as low back pain, migraines, and abdominal pain38. Further research has demonstrated that chronic pain disproportionately affects women and older adults and is often associated with obesity39. Systematic reviews have likewise found robust associations between obesity and headache, neuropathy, and other forms of chronic pain40,41. Our results align with prior research indicating that VAI serves as a reliable predictor in evaluating chronic pain and demonstrates greater predictive accuracy compared to conventional BMI measures.

Several mechanisms may explain the link between VAI and persistent pain, with elevated mechanical loading on weight-bearing joints being one of the most frequently cited factors. Studies have shown that obese individuals experience significantly higher disc pressures when lifting objects, increasing their risk for chronic pain42. Additionally, Obesity is believed to promote a low-grade chronic inflammatory state, with visceral adiposity playing a central role. This inflammatory process may modulate pain through elevated levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), and the accumulation of macrophages in adipose tissue43,44,45,46. The elevated prevalence of depression in both obesity and chronic pain populations also suggests that depression plays a mediating role in this relationship, research suggests that visceral fat levels may serve as a potential link between metabolic disorders and depression and that treating depression could help mitigate the connection between obesity and chronic pain38,47. Lastly, sedentary lifestyle factors are significantly and independently associated with the accumulation of visceral fat and may serve as a common risk factor for both obesity and chronic pain48,49,50. Taken together, these findings suggest that the association between VAI and chronic pain is likely the outcome of various intersecting biological and lifestyle pathways. Future study is necessary to clarify the underlying mechanisms to formulate more effective prevention and therapeutic strategies.

This research possesses several strengths. Firstly, it utilizes nationally representative, population-based sampling data from NHANES, with analyses weighted appropriately to ensure broad applicability. The study’s sample size is both representative and statistically robust. Additionally, we controlled for possible confounding factors and conducted subgroup analyses, which enhanced the reliability of our results. Furthermore, we investigated the nonlinear association between VAI and chronic pain, conducting sensitivity analyses to ensure our findings’ robustness. However, certain limitations should be noted. Owing to the cross-sectional approach, causal relationships between VAI and chronic pain cannot be established. Despite controlling for multiple covariates, residual confounding by unmeasured factors may still influence our results. Additionally, NHANES chronic pain data are limited to 1999–2004, restricting the study’s ability to assess changes over time.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates a notable link between VAI and an increased prevalence of persistent pain among US adults, underscoring the significance of managing visceral fat deposition to identify individuals at heightened risk for persistent pain. Nevertheless, additional large-scale prospective research investigations are required to validate and elucidate these findings.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were utilized in this research, and the data can be accessed at the following link: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

References

Raja, S. N. et al. The revised international association for the study of pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 161, 1976–1982. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939 (2020).

Treede, R. D. et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP classification of chronic pain for the international classification of diseases (ICD-11). Pain 160, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001384 (2019).

Breivik, H., Collett, B., Ventafridda, V., Cohen, R. & Gallacher, D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur. J. Pain. 10, 287–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009 (2006).

Goldberg, D. S. & McGee, S. J. Pain as a global public health priority. BMC Public. Health. 11, 770. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-770 (2011).

Cawley, J. & Meyerhoefer, C. The medical care costs of obesity: an instrumental variables approach. J. Health. Econ. 31, 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.10.003 (2012).

Lavie, C. J., McAuley, P. A., Church, T. S., Milani, R. V. & Blair, S. N. Obesity and cardiovascular diseases: implications regarding fitness, fatness, and severity in the obesity paradox. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63, 1345–1354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.022 (2014).

Stadler, J. T. & Marsche, G. Obesity-Related changes in High-Density lipoprotein metabolism and function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21238985 (2020).

Binvignat, M., Sellam, J., Berenbaum, F. & Felson, D. T. The role of obesity and adipose tissue dysfunction in osteoarthritis pain. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 20, 565–584. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-024-01143-3 (2024).

Liu, Y., Tang, G. & Li, J. Causations between obesity, diabetes, lifestyle factors and the risk of low back pain. Eur. Spine Journal: Official Publication Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deformity Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 33, 525–532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-08069-6 (2024).

Heuch, I., Heuch, I., Hagen, K. & Zwart, J. A. Overweight and obesity as risk factors for chronic low back pain: a new follow-up in the HUNT study. BMC Public. Health. 24, 2618. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-20011-z (2024).

Zhang, D. H., Fan, Y. H., Zhang, Y. Q. & Cao, H. Neuroendocrine and neuroimmune mechanisms underlying comorbidity of pain and obesity. Life Sci. 322, 121669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121669 (2023).

Rothman, K. J. BMI-related errors in the measurement of obesity. International journal of obesity () 32 Suppl 3, S56-59 (2008). (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.87

Okorodudu, D. O. et al. Diagnostic performance of body mass index to identify obesity as defined by body adiposity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of obesity () 34, 791–799 (2010). (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.5

Kolb, H. Obese visceral fat tissue inflammation: from protective to detrimental? BMC Med. 20, 494. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-022-02672-y (2022).

Fang, X. X. et al. Inflammation in pathogenesis of chronic pain: foe and friend. Mol. Pain. 19, 17448069231178176. https://doi.org/10.1177/17448069231178176 (2023).

Amato, M. C. et al. Visceral adiposity index: a reliable indicator of visceral fat function associated with cardiometabolic risk. Diabetes Care. 33, 920–922. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-1825 (2010).

Zhou, H., Li, T., Li, J., Zhuang, X. & Yang, J. The association between visceral adiposity index and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Sci. Rep. 14, 16634. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67430-x (2024).

Fan, Y. et al. Association between visceral adipose index and risk of hypertension in a middle-aged and elderly Chinese population. Nutrition, metabolism, and cardiovascular diseases: NMCD 31, 2358–2365 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2021.04.024

Chen, Q., Zhang, Z., Luo, N. & Qi, Y. Elevated visceral adiposity index is associated with increased stroke prevalence and earlier age at first stroke onset: based on a National cross-sectional study. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 1086936. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1086936 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Association of visceral adiposity index with sarcopenia based on NHANES data. Sci. Rep. 14, 21169. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72218-0 (2024).

Qin, Z. et al. Higher visceral adiposity index is associated with increased likelihood of abdominal aortic calcification. Clin. (Sao Paulo Brazil). 77, 100114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinsp.2022.100114 (2022).

Zhuang, J., Wang, Y., Wang, S., Hu, R. & Wu, Y. Association between visceral adiposity index and infertility in reproductive-aged women in the united States. Sci. Rep. 14, 14230. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64849-0 (2024).

Yang, Q., Wang, X., Li, C. & Wang, X. A cross-sectional study on the relationship between visceral adiposity index and periodontitis in different age groups. Sci. Rep. 13, 5839. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33082-6 (2023).

Yang, X. et al. Association between visceral adiposity index and bowel habits and inflammatory bowel disease: a cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 14, 23923. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73864-0 (2024).

Borrud, L. et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: national youth fitness survey plan, operations, and analysis, 2012. Vital and health statistics. Series 2, Data evaluation and methods research, 1–24 (2014).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet (London England). 370, 1453–1457. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61602-x (2007).

Nicholas, M. et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic primary pain. Pain 160, 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001390 (2019).

Johnson, C. L. et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: analytic guidelines, 1999–2010. Vital and health statistics. Series 2, Data evaluation and methods research, 1–24 (2013).

Malheiros, T. Obesity and its chronic inflammation as pain potentiation factor in rats with osteoarthritis. Cytokine 169, 156284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2023.156284 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Chronic pain and its association with obesity among older adults in China. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 76, 12–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2018.01.009 (2018).

Donini, L. M., Pinto, A., Giusti, A. M., Lenzi, A. & Poggiogalle, E. Obesity or BMI paradox?? Beneath the tip of the iceberg. Front. Nutr. 7, 53. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2020.00053 (2020).

Simati, S., Kokkinos, A., Dalamaga, M. & Argyrakopoulou, G. Obesity paradox: fact or fiction?? Curr. Obes. Rep. 12, 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-023-00497-1 (2023).

Xu, M., Zhou, H., Zhang, R., Pan, Y. & Liu, X. Correlation between visceral adiposity index and erectile dysfunction in American adult males: a cross-sectional study based on NHANES. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1301284. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1301284 (2023).

Qin, Z., Chen, X., Sun, J. & Jiang, L. The association between visceral adiposity index and decreased renal function: A population-based study. Front. Nutr. 10, 1076301. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1076301 (2023).

Kim, B., Kim, G. M. & Oh, S. Use of the visceral adiposity index as an Indicator of chronic kidney disease in older adults: comparison with body mass index. J. Clin. Med. 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216297 (2022).

Hoftun, G. B., Romundstad, P. R. & Rygg, M. Factors associated with adolescent chronic non-specific pain, chronic multisite pain, and chronic pain with high disability: the Young-HUNT study 2008. J. Pain. 13, 874–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2012.06.001 (2012).

Hitt, H. C., McMillen, R. C., Thornton-Neaves, T., Koch, K. & Cosby, A. G. Comorbidity of obesity and pain in a general population: results from the Southern pain prevalence study. J. Pain. 8, 430–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2006.12.003 (2007).

Wright, L. J. et al. Chronic pain, overweight, and obesity: findings from a community-based twin registry. J. Pain. 11, 628–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.004 (2010).

McCarthy, L. H., Bigal, M. E., Katz, M., Derby, C. & Lipton, R. B. Chronic pain and obesity in elderly people: results from the Einstein aging study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 57, 115–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02089.x (2009).

Chai, N. C., Scher, A. I., Moghekar, A., Bond, D. S. & Peterlin, B. L. Obesity and headache: part I–a systematic review of the epidemiology of obesity and headache. Headache 54, 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12296 (2014).

Miscio, G. et al. Obesity and peripheral neuropathy risk: a dangerous liaison. J. Peripheral Nerv. System: JPNS. 10, 354–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1085-9489.2005.00047.x (2005).

Singh, D., Park, W., Hwang, D. & Levy, M. S. Severe obesity effect on low back Biomechanical stress of manual load lifting. Work (Reading Mass). 51, 337–348. https://doi.org/10.3233/wor-141945 (2015).

Ronti, T., Lupattelli, G. & Mannarino, E. The endocrine function of adipose tissue: an update. Clin. Endocrinol. 64, 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02474.x (2006).

Blüher, M. et al. Association of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, interleukin-10 and adiponectin plasma concentrations with measures of obesity, insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism. Experimental and clinical endocrinology & diabetes: official journal. German Soc. Endocrinol. [and] German Diabetes Association. 113, 534–537. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-872851 (2005).

Weisberg, S. P. et al. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Investig. 112, 1796–1808. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci19246 (2003).

Wellen, K. E. & Hotamisligil, G. S. Obesity-induced inflammatory changes in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Investig. 112, 1785–1788. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci20514 (2003).

Liu, H. et al. The association between metabolic score for visceral fat and depression in overweight or obese individuals: evidence from NHANES. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1482003. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1482003 (2024).

Wareham, N. J., van Sluijs, E. M. & Ekelund, U. Physical activity and obesity prevention: a review of the current evidence. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 64, 229–247 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1079/pns2005423

Whitaker, K. M., Pereira, M. A., Jacobs, D. R. Jr., Sidney, S. & Odegaard, A. O. Sedentary behavior, physical activity, and abdominal adipose tissue deposition. Med. Sci. Sports. Exerc. 49, 450–458. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000001112 (2017).

Galmes-Panades, A. M. et al. Lifestyle factors and visceral adipose tissue: results from the PREDIMED-PLUS study. PloS One. 14, e0210726. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210726 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the NHANES database and all participants in the survey for their generosity and willingness to contribute.

Funding

This research was supported by the Youth Scientific Research Fund of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (QDFYQN2023226).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.X: conducted the research and wrote the manuscript. R.S and Y.Z: analyzed the data. W.F: critically revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and endorsed the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, W., Shi, R., Zhu, Y. et al. Association of visceral adiposity index and chronic pain in US adults: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 9135 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93041-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93041-1