Abstract

To investigate the prospective association of frailty status, especially the early stage, with the long-term risk of Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in a large prospective cohort. We included participants who were free of GERD and cancer at baseline and use of aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) from the UK Biobank (UKB). Frailty status was assessed using Fried phenotype including five items (weight loss, exhaustion, low grip strength, low physical activity, slow walking pace) and classified as non-frail, pre-frail, and frail. The outcome was incident GERD. The frailty status was assessed using Cox proportional hazard model. Among 327,965 participants (mean age 56.6 years) at baseline, 151,689 (46.3%) were pre-frail and 14,288 (4.4%) were frail. During a median of 13.5-years of follow-up, 31,027 (9.5%) participants developed GERD. Compared with non-frail participants, pre-frail (hazard ratios [HR] = 1.21, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.18–1.24) and frail (HR = 1.60, 95% CI 1.52–1.68) participants had significantly higher risks of GERD. Among the five indicators of frailty, exhaustion demonstrated the strongest association with the risk of GERD (HR = 1.42, 95% CI 1.38–1.47). Subgroup analysis showed strong associations among younger (< 60 years), female, high-educated, unemployed participants, and those who had BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 (all P for interaction < 0.05). Frailty, especially pre-frail, which is potentially reversible, was associated with higher risk of GERD in middle-aged and older individuals. The findings underscore the importance of integrating routine frailty assessments and interventions, especially at the early stage, to improve digestive health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a chronic disorder, characterized by reflux of stomach contents causing troublesome symptoms or complications1. The typical symptoms include heartburn, regurgitation, and chest pain. The estimated prevalence of GERD is 13.3% of the population worldwide and 15.4% in North America2,3. The incidence rate in the UK has also reached 5 per 1000 people4. Due to the chronic nature of GERD and the side effects associated with long-term use of conventional medications, this disorder exerts a substantial economic burden and impact on quality of life5. Given the rapidly aging population and increased lifespan, the number of older adults with GERD is rising, with a prevalence of 14.0% in people aged < 50 years old and 17.3% in those ≥ 50 years suggesting a remarkable rise in symptom prevalence with increasing age2.

Frailty is a major public health problem for an aging society, defined as a state of decreased reserve and resistance to stressors, characterized by a functional decline in multiple systems, and may be improved with targeted intervention6,7. In the cardiovascular system, frailty may lead to a significant decrease in the innate immune system, T cell activity, antibody production, and increased oxidative stress in mitochondrial activity, resulting in elevated levels of serum inflammation. High inflammatory levels and frailty can increase mortality, morbidity, hospitalization rate, disability, and co-morbidity onset of cardiovascular disease8. In addition, frailty may reduce the immune defense of the intestine, affect intestinal permeability, and accelerate the risk of digestive system diseases9,10. Frailty and pre-frailty are associated with an increased risk of digestive disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)11,12, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)13, gastric and colorectal cancer14,15. Currently, preventions for frailty include frailty screening, case identification, and management16. Regular exercise and physical activity are effective strategies for managing frailty, which can reduce the adverse prognosis and progression of frailty and liver cirrhosis17. Preoperative frailty can have a negative impact on various postoperative outcomes for patients with digestive system tumors. Developing frailty intervention measures can improve the overall condition of digestive system tumor patients during the perioperative and long-term recovery periods18.

The risk factors for GERD, such as aging, smoking, anxiety/depression, low physical activity, relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, decreased esophageal clearance ability, and delayed gastric emptying, are closely related to frailty19,20,21. Moreover, a cross-sectional study reported that a decline in muscle strength, one of the components of frailty, is associated with GERD in the elderly population22. Thus, we hypothesized that frailty is associated with increased risk of GERD. We aim to find frailty factors that are critical in developing a higher risk of GERD. To address these knowledge gaps, we aimed to explore the prospective association between frailty and its items and the risk of GERD in middle-aged and older adults from the UKB (Fig. S1).

Methods

Study participants

The UK Biobank began in 2006 and is a large-scale cohort study with a long-term follow-up and with the recruitment of approximately 500,000 adults in the United Kingdom23. UKB was approved by the North West-Haydock Research Ethics Committee and all participants electronically wrote informed consent at recruitment. All the participants completed baseline questionnaires and underwent physical assessment. More details can be accessed on the official UKB website (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/).

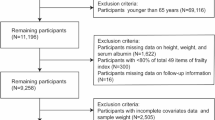

Among 502,018 UKB participants, by excluding these criteria, we were able to obtain a more homogeneous sample population to better evaluate the association between pre-frailty status and GERD. Those with prevalent GERD (n = 36,705) and cancer (n = 39,018) at baseline were excluded (see details in Figure S1). Next, participants with missing data on any of the frailty items (weight loss, n = 8916; exhaustion, n = 12,698; low physical activity, n = 74,882; low grip strength, n = 1807; slow walking pace, n = 212) were also excluded. Finally, 327,965 participants were included (Fig. S1).

Frailty measurements

In our study, we applied the Frailty phenotype (FP), a widely recognized and adopted measurement for physical frailty, proposed by Fried and colleagues24. Handgrip strength was used as an objective measure of weakness, and the other four items (unintentional weight loss, exhaustion, slow gait speed, and low physical activity) were assessed via self-reported questionnaires (see details in Table S1). The FP score ranged from 0 to 5, indicative of frailty severity, with a higher score reflecting greater frailty. Based on previous studies, participants were classified as non-frail (FP score of 0), pre-frail (FP score ≥ 1 and ≤ 2), and frail (FP score ≥ 3)24,25. Briefly, FP was assessed with five items: unintentional weight loss, exhaustion, weakness, slow gait speed, and low physical activity, aligning with prior study conducted within the UKB18. Participants were first asked, "Compared with one year ago, has your weight changed?" Those who responded with "Yes, lost weight" received 1 point for unintentional weight loss; all other responses scored 0 points. Secondly, exhaustion was evaluated by asking participants how often they had felt tired or had little energy over the past two weeks. If a participant reported feeling this way more than half the days or nearly every day, they scored 1 point; otherwise, they scored 0 points. Weakness was measured using grip strength with a Jamar J00105 hydraulic hand dynamometer (Lafayette Instrument). Participants performed one grip assessment for each hand, and the maximal value from either hand was used. For men, scores of ≤ 29 kg for BMI ≤ 24 kg/m2, ≤ 30 kg for BMI 24.1–26 kg/m2, ≤ 30 kg for BMI 26.1–28 kg/m2, and ≤ 32 kg for BMI > 28 kg/m2 resulted in 1 point; for women, scores of ≤ 17 kg for BMI ≤ 23 kg/m2, ≤ 17.3 kg for BMI 23.1–26 kg/m2, ≤ 18 kg for BMI 26.1–29 kg/m2, and ≤ 21 kg for BMI > 29 kg/m2 also resulted in 1 point; otherwise, they scored 0 points. Slow gait speed was assessed by asking participants to describe their usual walking pace. Those who reported a slow pace scored 1 point; all others scored 0 points. Finally, low physical activity was evaluated by asking if participants engaged in any light DIY activities, heavy DIY activities, or strenuous sports in the last four weeks. If a participant reported none or only light activity with a frequency of once per week or less, they scored 1 point; otherwise, they scored 0 points.

Outcomes

The outcome of this study was the incidence of GERD. The UKB documents the onset of a wide range of health outcomes via an inclusive categorization system, drawing from diverse sources: primary care databases, hospital admission records, self-reported medical conditions, and death register records. These outcomes are consistently mapped to ICD-10 classifications and refreshed periodically. The time-to-event was calculated from the baseline to the occurrence of GERD, death, loss to follow-up, or end of follow-up (September 1, 2023), whichever came first. Among the 31,027 incident cases, 2999 cases were from individuals under primary care, 25,900 cases were recorded through hospital admissions data, and 2128 cases were self-reported.

Covariates

The covariates in this study included age, sex (female or male), ethnicity (white, non-white), Townsend deprivation index (TDI), occupation (employed and unemployed), education (high, intermediate, low), body mass index (BMI, < 18.5 kg/m2, 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, 25.0–29.9 kg/m2, ≥ 30 kg/m2), smoking status (never, previous, current), alcohol drinking status (never, previous, current), use of aspirin and NSAIDs, history of anxiety, depression, diabetes, hypertension, and upper gastroenterology diseases (UGID). The TDI was calculated based on areas before participants were recruited in the UKB, with a higher TDI indicating a lower level of socioeconomic status26. Education level was defined as high (college or university degree), intermediate (A/AS levels or O levels/GCSEs or equivalent), and low (none of the aforementioned)27. BMI was calculated as measured weight/height2 (kg/m2).

Statistical analysis

The basic characteristics of the study participants were classified by frailty status. Continuous variables were described by mean (standard deviation) and categorical variables by counts (percentages). Continuous variables were compared by analysis of variance, and categorical variables were compared by Chi-Squared test. The differences in cumulative GERD hazards among categories by frailty status were compared through Kaplan–Meier curves. Additionally, the proportional hazards assumption was assessed using Schoenfeld residuals. Cox proportional hazard regression models were applied to calculate the hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) between frailty and incident GERD. For both frailty status (non-frail, pre-frail, frail) and frailty score (continuous variable), two adjustment models were performed: (1) model 1, adjusted for age and sex; (2) model 2, additionally adjusted for TDI, ethnics, occupation, education, smoking status, drinking status, BMI, aspirin use, NSAIDs use, history of anxiety, depression, diabetes, hypertension, and UGID based on model 1. Tests for trend were performed by assigning median frail score values (0, 1, and 3) to each frailty status.

Subgroup analyses were conducted by age (< 60 years or ≥ 60 years), sex (male or female), education (high, intermediate, or low), occupation (employed or unemployed), BMI (< 18.5 kg/m2, 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, 25.0–29.9 kg/m2, ≥ 30 kg/m2). Potential effect modifications were explored by assessing the interaction between items of each stratified variable and frailty status. To test the robustness of the findings, we conducted several additional analyses. First, we repeated the main analysis by excluding participants taking anti-acid drugs at baseline such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) (The identification codes are detailed in Text S1). Second, we excluded participants with prevalent anxiety, depression, diabetes, hypertension, and UGID at baseline, respectively. Third, participants diagnosed with GERD within the first 2 years of follow-up were excluded to minimize the potential reverse causation. Fourth, frailty status was subsequently categorized as non-frail (score: 0–2), frailty (score: 3–5), and then we repeated the main analyses.

All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.1). A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant (two-sided).

Results

Basic characteristics

The characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. A total of 327,965 participants (mean age 56.6 years, 46.9% males) were enrolled in the final analyses. The prevalence of prefrailty and frailty at baseline was 46.3% (151,689/327,965) and 4.4% (14,288/327,965), respectively. Pre-frail and frail participants were more likely to be female, have a lower educational level, unemployed, have a higher level of TDI and BMI, and have a higher proportion of current smoking, prevalent anxiety, depression, diabetes, and UGID compared with the non-frail adults.

Frail status and the risk of GERD

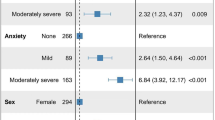

During a mean follow-up of 13.5 years, 31,027 (9.5%) GERD cases were recorded. As shown in Fig. 1, compared with non-frail, participants in pre-frail and frail groups showed a significant risk of GERD (HR = 1.21, 95% CI [1.18–1.24] for pre-frail; HR = 1.60, 95% CI [1.52–1.68] for frail; P for trend < 0.001) after adjustment for age, sex, Townsend deprivation index, ethnics, occupation, education, smoking status, drinking status, BMI, history of anxiety, depression, diabetes, hypertension, and UGID. Each of the five items of frailty showed independent associations with the risk of GERD (HR ranged from 1.10 to 1.43). Specifically, exhaustion (HR = 1.42, 95% CI [1.38, 1.47]) demonstrated the strongest association with GERD incidence, while low physical activity showed the least significant association (HR = 1.10, 95% CI [1.07, 1.13]). Besides, an 18% excess risk was associated with a per 1 frailty score change (HR = 1.18, 95% CI [1.16–1.20]). The higher risk of GERD during follow-up was confirmed by the cumulative hazard curve, adjusted for the aforementioned multiple covariates (Fig. 2).

Associations between frailty status and the risk of GERD. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; Model 1, adjusted for age and sex; Model 2, additionally adjusted for TDI, ethnics, occupation, education, smoking status, drinking status, BMI, aspirin use, NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) use, history of anxiety, depression, diabetes, hypertension, and upper gastroenterology disease.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

We conducted subgroup analyses by age, sex, education, occupation, and BMI to identify potential effect modifiers (Table 2). The results showed that the associations between frailty and risk of GERD were more pronounced among younger participants (< 60 years), female, unemployed, with high education, and lowest BMI (all P for interaction < 0.05). For instance, among participants aged below 60 years, compared with no-frail, participants in pre-frail and frail group had increased risks of GERD, with HRs of 1.24 (95% CI 1.20–1.29), 1.72 (95% CI 1.60–1.85), respectively (P for trend < 0.001).

Results of sensitivity analysis by frailty status were all consistent with main findings when (1) excluding participants with oral PPI/H2RA or anti-acid therapy on the onset of GERD (Table S2); (2) excluding participants with prevalent anxiety, depression, diabetes, hypertension at baseline (Table S3-S6); (3) excluding participants diagnosed with other UGIDs (esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal stricture, esophageal varices, gastric/stomach ulcers, gastritis/gastric erosions, gastrointestinal bleeding) (Table S7); (4) subsequently categorizing the frailty as non-frail (score: 0 to 2), frail (score: 3 to 5) (Table S8); (5) excluding participants with the onset of GERD within 2 years of follow-up (Table S9).

Discussion

In this large-scale, long-term prospective cohort study, we demonstrated for the first time that both participants with pre-frailty and frailty were associated with higher risks of GERD. Among the five items of frailty, exhaustion showed the strongest association with the risk of GERD. Subgroup analysis showed strong associations among participants < 60 years old, female, unemployed, with high education, and lowest BMI. These findings have emphasized the critical role of frailty in the development of GERD risk and stratifying the populations.

Previous studies had found that frailty increased the risks of adverse health outcomes including falls, disability, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality28,29,30. Considering the potential adverse impact of pre-frailty and frailty on GERD occurrence, screening frailty status may have important implications for the detection, diagnosis, and treatment of GERD. Notably, our findings showed that participants under 60 in the pre-frail or frail condition exhibit a notably elevated risk of GERD, underscoring the heightened significance of frailty screening within this middle-aged demographic. Since frailty status is a modifiable process with transitions among being frail, pre-frail, and non-frail over time, identifying those with pre-frail early may have more profound public health significance for GERD occurrence31. Moreover, our research reveals a significant association between exhaustion and the risk of GERD, highlighting the need to enhance screening for exhaustion and to prioritize the improvement of mental well-being in these individuals to prevent or mitigate the onset of GERD.

Although there has been no comparable data examining frailty status with the risk of GERD yet, studies have investigated the association between frailty items and GERD, supporting our findings22,32,33. A recent cross-sectional analysis of 542 older adults reported an independent and inverse relationship between grip strength with GERD22. Our study also revealed that low grip strength can increase the risk of developing GERD by 20%. Another study from South Korea analyzed 8218 samples and found that sarcopenia was an independent predictor of GERD33, and the causal relationship has been confirmed by a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study32. Drawing upon these findings, we speculate that skeletal muscle attenuation often co-occurs with a corresponding decrease in smooth muscle mass, especially the insufficient strength of the lower esophageal sphincter, which may lead to the reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus. Consequently, among individuals predisposed to GERD, it is imperative to identify those exhibiting skeletal muscle attenuation, which could extend to populations afflicted with frailty, given the close association between frailty and sarcopenia34,35.

Frailty and GERD share similar pathophysiological mechanisms, such as systemic inflammation, and gut microbiota. Previous studies have demonstrated the upregulation of the proinflammatory cytokines (i.e., TNF-α, IL-1/6) in older adults both with frailty and pre-frailty36,37, which are associated with impaired esophageal mucosal integrity, and may accordingly facilitate the development of GERD38. Besides, age-related gut microbiota changes increase intestinal permeability, resulting in the translocation of microorganisms and harmful substances, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), into the bloodstream39,40. LPS may worsen reflux esophagitis by relaxing the lower esophageal sphincter and slowing gastric emptying, suggesting a complex link between aging, microbiome imbalance, and GERD development41. Nevertheless, further large prospective population-based cohort studies to validate this positive association and elucidate the potential mechanism, especially on onset GERD, are needed.

To date, several feasible interventions aimed at improving core strength have been proven helpful for both prevention and improvement of frailty in older adults, such as exercise, physical therapy, adequate diet, and nutrition interventions42,43. It has been suggested that pre-frailty is a reversible clinical condition if treated in the early stages24. Thus, early, and timely screening and intervention for pre-frailty not only reduce the risk of GERD but also contribute significantly to the effective management and treatment of GERD.

The major novelty of the current study is to highlight the long-term risk of incident GERD associated with pre-frailty and frailty in middle-aged and older adults for the first time, based on the large-scale and well-designed longitudinal cohort. Meanwhile, various sensitivity analyses ensured the robustness of the findings. Several limitations in this study should also be considered. First, given that the status of frailty might be changed during the follow-up period, we were unable to thoroughly explore how shifts in frailty status impact GERD susceptibility. The current assessment of the impact of frailty on GERD may have biases, but it does not alter the conclusion. In the future, if there are multiple rounds of data on frailty assessment, we may explore the impact of frailty changes on GERD occurrence. Second, frail individuals’ heightened healthcare utilization and increased medical testing may lead to an over-representation of GERD diagnoses, leading to detection bias, as compared to the non-frail population. Third, the majority of UKB participants were White, with a higher socioeconomic level, and relatively healthy, which may limit the broad application of our findings to more diverse ethnic and socioeconomic demographics. Fourth, the limitations in the definition of frailty arise from deficiencies in the reporting, such as the use of single questions to assess criteria like weight loss and slowness, which may not fully capture the complexity of the frailty phenotype. However, this methodology is also extensively employed in other research studies44,45,46. Finally, our longitudinal associations do not imply causality, and hence more studies are needed to validate these findings.

Conclusions

In this prospective cohort study of middle-aged and older UKB participants, both pre-frailty and frailty were significantly associated with increased risks of GERD. These findings highlight the importance of frailty status management in the prevention and intervention of GERD. Detecting pre-frailty at an early stage and implementing timely preventions may help to improve the allocation of health care resources and to reduce GERD-related burden.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in UK Biobank at www.ukbiobank.ac.uk, reference number 61856.

Abbreviations

- ACG:

-

American College of Gastroenterology

- AGA:

-

American gastroenterological association

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- FP:

-

Frailty phenotype

- GERD:

-

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- IBS:

-

Irritable bowel syndrome

- H2RAs:

-

Histamine 2 receptor antagonists

- HR:

-

Hazard ratios

- ICD-10:

-

International classification of diseases 10th revision code

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- NSAID:

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- TDI:

-

Townsend deprivation index

- PPI:

-

Proton pump inhibitors

- UGID:

-

Upper gastroenterology diseases

- UKB:

-

UK Biobank

References

Fass, R. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 1207–1216. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp2114026 (2022).

Eusebi, L. H. et al. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: A meta-analysis. Gut 67, 430–440. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313589 (2018).

Tack, J., Becher, A., Mulligan, C. & Johnson, D. A. Systematic review: the burden of disruptive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 35, 1257–1266. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05086.x (2012).

Ronnie, F. et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-021-00287-w (2021).

Dent, J. et al. Accuracy of the diagnosis of GORD by questionnaire, physicians and a trial of proton pump inhibitor treatment: the Diamond Study. Gut 59, 714–721. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2009.200063 (2010).

Fried, L. P. et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 56, M146–M157. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 (2001).

Clegg, A., Young, J., Iliffe, S., Rikkert, M. O. & Rockwood, K. Frailty in elderly people. The Lancet 381, 752–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9 (2013).

Pınar, S., Ferhat, A., Lee, S., Sarah, J. & Ahmet Turan, I. Inflammation, frailty and cardiovascular disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33330-0_7 (2020).

Javier, A., El Mariam, A., Alejandro, Á. B. & Leocadio, R.-M. Physical activity and exercise: Strategies to manage frailty. Redox Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2020.101513 (2020).

Walston, J. et al. Frailty and activation of the inflammation and coagulation systems with and without clinical comorbidities: Results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 162, 2333–2341. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.162.20.2333 (2002).

Zhang, Q. et al. Frailty and pre-frailty with long-term risk of elderly-onset inflammatory bowel disease: A large-scale prospective cohort study. Ann. Epidemiol. 88, 30–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2023.10.006 (2023).

Singh, S. et al. Frailty and risk of serious infections in biologic-treated patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 27, 1626–1633. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izaa327 (2020).

Wu, S. et al. Frailty status and risk of irritable bowel syndrome in middle-aged and older adults: A large-scale prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 56, 101807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101807 (2023).

Liu, F. et al. Associations of physical frailty with incidence and mortality of overall and site-specific cancers: A prospective cohort study from UK biobank. Prev. Med. 177, 107742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2023.107742 (2023).

Mak, J. K. L., Kuja-Halkola, R., Wang, Y., Hägg, S. & Jylhävä, J. Can frailty scores predict the incidence of cancer? Results from two large population-based studies. Geroscience 45, 2051–2064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-023-00783-9 (2023).

Dent, E. et al. Management of frailty: Opportunities, challenges, and future directions. The Lancet 394, 1376–1386. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31785-4 (2019).

Elsheikh, M. et al. Frailty in end-stage liver disease: Understanding pathophysiology, tools for assessment, and strategies for management. World J. Gastroenterol. 29, 6028–6048. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v29.i46.6028 (2023).

Ding, L. et al. Effects of preoperative frailty on outcomes following surgery among patients with digestive system tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 47, 3040–3048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2021.07.019 (2021).

Bisgaard, T. H., Allin, K. H., Keefer, L., Ananthakrishnan, A. N. & Jess, T. Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: Epidemiology, mechanisms and treatment. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 19, 717–726. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-022-00634-6 (2022).

Zamani, M., Alizadeh-Tabari, S., Chan, W. W. & Talley, N. J. Association between anxiety/depression and gastroesophageal reflux: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 118, 2133–2143. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000002411 (2023).

Clarrett, D. M. & Hachem, C. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Mo. Med. 115, 214–218 (2018).

Song, B. K., Brellenthin, A. G., Saavedra, J. M. & Lee, D. C. Associations between muscular strength and gastroesophageal reflux disease in older adults. J. Phys. Act. Health 18, 1207–1214. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2021-0013 (2021).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK biobank: An open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12, e1001779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779 (2015).

Fried, L. P. et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56, M146-156. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146 (2001).

Hanlon, P. et al. Frailty and pre-frailty in middle-aged and older adults and its association with multimorbidity and mortality: A prospective analysis of 493 737 UK Biobank participants. Lancet Public Health 3, e323–e332. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(18)30091-4 (2018).

Chudasama, Y. V. et al. Healthy lifestyle and life expectancy in people with multimorbidity in the UK Biobank: A longitudinal cohort study. PLoS Med. 17, e1003332. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003332 (2020).

Zhang, Y. B. et al. Associations of healthy lifestyle and socioeconomic status with mortality and incident cardiovascular disease: Two prospective cohort studies. Bmj 373, n604. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n604 (2021).

Si, H. et al. Predictive performance of 7 frailty instruments for short-term disability, falls and hospitalization among Chinese community-dwelling older adults: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 117, 103875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103875 (2021).

Damluji, A. A. et al. Frailty and cardiovascular outcomes in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Eur. Heart J. 42, 3856–3865. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab468 (2021).

Kojima, G., Iliffe, S. & Walters, K. Frailty index as a predictor of mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 47, 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx162 (2018).

Kojima, G., Taniguchi, Y., Iliffe, S., Jivraj, S. & Walters, K. Transitions between frailty states among community-dwelling older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 50, 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2019.01.010 (2019).

Hu, R., Liu, C. & Li, D. A Mendelian randomization analysis identifies causal association between sarcopenia and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Aging (Albany NY) 16, 4723–4735. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.205627 (2024).

Kim, Y. M. et al. Association between skeletal muscle attenuation and gastroesophageal reflux disease: A health check-up cohort study. Sci. Rep. 9, 20102. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56702-6 (2019).

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. & Sayer, A. A. Sarcopenia. Lancet 393, 2636–2646. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31138-9 (2019).

Ye, L. et al. Frailty and sarcopenia: A bibliometric analysis of their association and potential targets for intervention. Ageing Res. Rev. 92, 102111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.102111 (2023).

Van Epps, P. et al. Frailty has a stronger association with inflammation than age in older veterans. Immun. Ageing 13, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12979-016-0082-z (2016).

Soysal, P. et al. Inflammation and frailty in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 31, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2016.08.006 (2016).

Ergun, P., Kipcak, S., Gunel, N. S., Bor, S. & Sozmen, E. Y. Roles of cytokines in pathological and physiological gastroesophageal reflux exposure. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm22186 (2023).

Thevaranjan, N. et al. Age-associated microbial dysbiosis promotes intestinal permeability, systemic inflammation, and macrophage dysfunction. Cell Host Microbe 21, 455-466.e454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2017.03.002 (2017).

Sovran, B. et al. Age-associated impairment of the mucus barrier function is associated with profound changes in microbiota and immunity. Sci. Rep. 9, 1437. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35228-3 (2019).

Yang, L., Francois, F. & Pei, Z. Molecular pathways: Pathogenesis and clinical implications of microbiome alteration in esophagitis and Barrett esophagus. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 2138–2144. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-11-0934 (2012).

Cesari, M. et al. A physical activity intervention to treat the frailty syndrome in older persons-results from the LIFE-P study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 70, 216–222. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glu099 (2015).

Rahi, B. et al. High adherence to a Mediterranean diet and lower risk of frailty among French older adults community-dwellers: Results from the Three-City-Bordeaux Study. Clin. Nutr. 37, 1293–1298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2017.05.020 (2018).

Deng, M. G. et al. Association between frailty and depression: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi3902. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adi3902 (2023).

Jiang, R. et al. Associations of physical frailty with health outcomes and brain structure in 483 033 middle-aged and older adults: a population-based study from the UK Biobank. Lancet Digit. Health 5, e350–e359. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2589-7500(23)00043-2 (2023).

Hanlon, P. et al. Frailty and pre-frailty in middle-aged and older adults and its association with multimorbidity and mortality: A prospective analysis of 493 737 UK Biobank participants. The Lancet Public Health 3, e323–e332. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(18)30091-4 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all adults who participated in the UKB.

Funding

This work was supported by Grants from Zhejiang University School of Public Health Interdisciplinary Research Innovation Team Development Project, Key Laboratory of Intelligent Preventive Medicine of Zhejiang Province [grant numbers 2020E10004], and Zhejiang University Global Partnership Fund. The funders had no role in the study design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZYL designed the study. LP analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study involves human participants and was approved by The UKB and received ethical approval from the North West Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee (REC reference for UK Biobank 11/ NW/0382). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part. All experiments were performed in line with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, L., Li, X., Qi, J. et al. Pre-frailty is associated with higher risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a large prospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 8916 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93114-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93114-1