Abstract

The track regularity with high accuracy is crucial important to protect the dynamic safety in high speed and heavy haul railways, normally, the inertial measurement unit (IMU)is capable to provide the precise solution for track irregularity measurement. However, to achieve high accuracy, the most existing track irregularity measurement methods seriously depended on the fiber-optic IMU, it is very expensive, also with larger size and weight, while the growing availability of low-cost and small size MEMS-IMU can yield acceptable accuracy for track irregularity by using multiple MEMS-IMUs fusion and particular geometric constraints. For these reasons, this paper proposes an accurate measurement method for track irregularity that combines the multiple MEMS-IMUs and special geometric constraints, which can be obtained noticeable measuring performances compared with fiber-optic IMU. To achieve this, we first construct the geometric constraint models for multiple MEMS-IMUs and establish their optimal installation configuration. Subsequently, an adaptive federal Kalman filter (AFKF) is developed to fuse the multiple local MEMS-IMUs information into the global filter, which can adaptive adjustment each MEMS-IMU sub-filter fusion factor and feedforward factor to obtain the highly estimation accuracy for track irregularity. Finally, the test results from both laboratory and field environment prove that the measurement accuracy of track irregularity using our proposed method are very close to the fiber-optic IMU method, and indicate a significant step forward in the track irregularity with the low-cost and small size MEMS-IMU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Up to now, the high speed and heavy haul railways have been played an important role in China, the track irregularity measuring with high accuracy is significantly important to protect its dynamic safety of railways and the comfort of the passengers. However, due to the train ground-borne vibration and noise, the values of track irregularity will deviate from its normal value after the train run a period of time. Especially, when the track irregularity exceeding the designed alert limit, it will be caused rapid degradation of the rails. In recently years, the commonly used measuring methods for track irregularity are total station-based inspection system and high-precision fiber-optic IMU1,2. The total station-based inspection system utilizes the automated total stations combined with the gauge sensor, also controlled point with integrated positioning system (CPIII) control network to obtain the track geometric parameters information. During the measurement, the total station inspection system will stop at the exact positions to measure the track irregularity and compare with the CPIII control points to ensure its measurement accuracy, after that moving to the next positions to repeat the above processes. Obviously, the measurement modes of stop–go of total station-based inspection system are time-consuming and dramatically hinders measurement speed for track irregularity, leaded to it is unaccepted in track irregularity fast measurement3,4,5.

To simultaneously improve the measurement efficiency and accuracy for track irregularity, the fiber-optic IMU combined with global navigation satellite system (GNSS) have given rise to great interests in the track irregularity inspection. Generally, the GNSS combined fiber-optic IMU can achieve high measurement accuracy through decreasing the accumulated errors of fiber-optic IMU assisting with GNSS. Therefore, the combining method of fiber-optic IMU and GNSS can effectively improve the measurement accuracy and efficiency at the same time. Nowadays, many researchers have focused on this area, for example: Chen et al.6 developed a track inspection system adopting GNSS combined fiber-optic IMU integration as the main equipment and reaching millimeter level relative accuracy. Updates of the GNSS position and velocity in the vehicle frame were used to build the measurement model in the filter. Chen7 also illustrated the error prorogation process. Employing a simplified INS error equation, the transfer function between the error source and the track deviation was obtained, and the simulated response of the main error source was revealed. Instead of using GNSS Real-Time Kinematic (RTK). Zhu et al.8 developed a GNSS/INS/TS integrated irregularity measurement method using to the attitude-inferred track irregularity measurement. Zhu et al.9 also developed an attitude measurement approach using double-differenced GNSS and INS integration to detect deformation in railway track irregularity measurement.

Although the fiber-optic IMU can obtain the higher accuracy for track irregularity, while the fiber-optic IMU is usually very expensive, also with larger size and weight, led to a drop in the track irregularity measurement applications. With the improvement of manufacturing level, the cost and size of MEMS-IMU can be reduced at the same time. Whereas comparing with the fiber-optic IMU, the decrease in the cost of MEMS-IMU will be also resulted in drop in the measurement accuracy. In consideration of the small size and low-cost of MEMS-IMU, it is allowed to integrating multiple MEMS-IMUs into a system to improve the system overall measurement accuracy10,11,12. Moreover, comparing with a single MEMS-IMU configuration, the multiple MEMS-IMUs integration could improve the system overall performances at the follows aspects. First of all, the fault and spurious measurements of single MEMS-IMU may be detected and isolated, which could improve the robustness and accuracy of the system. Subsequently, the intrinsic noise of multiple MEMS-IMUs can be effectively induced according to the special geometric constraint13,14,15.

Generally, the low-cost MEMS-IMU can be improved the measurement accuracy of the system through multiple sensors fusion. However, now few researchers focused on integrating multiple IMUs installed with different geometrical configuration to improve the system measurement or navigation accuracy. In the field of multiple MEMS-IMUs navigation, some researches have used the observation-level methods to fuse several MEMS-IMUs outputs into a single virtual MEMS-IMU to improve the system measurement accuracy. For example, Zhu et al.16 mounted two MEMS-IMUs on the two wheels of the train to mitigate the error drift of the onboard MEMS-IMU. However, these approaches are not suitable for our problem because, in our design, the IMUs are distributed in different geometrical configuration on the train to perceive accurate different track irregularity. Otherwise, the ideas of fusing multiple MEMS-IMUs information and taking advantage of their relative geometrical constraints are similar to the dual foot-mounted MEMS-IMUs navigation system. Generally, they are two main methods to implement the relative geometrical constraints between the two MEMS-IMUs on the dual foot navigation system: inequality geometrical constraints and equality geometrical constraints. However, unlike the 2D dual foot-mounted MEMS-IMUs navigation system, the relative positions of the MEMS-IMUs mounted on the train bogie platform or wheels center are layout on 3Ddistribution17,18,19,20. Therefore, we can straightforwardly use the 3D space relationships instead of the 2D relationships to constrain the multiple MEMS-IMUs’ distribution, moreover, the 3D spatial relationship involves much richer information thus it will make the multiple MEMS-IMUs geometrical constraints more reliable and accurate.

For these reasons, we propose a novel method for track irregularity measurement combines the multiple IMUs and special geometric constraints, which is able to obtain noticeable measurement performance compared to the fiber-optic IMU. The mainly contributions of this paper can be summarized as21,22,23,24,25,26:

-

(1)

We construct the 3D geometric constraint models for multiple MEMS-IMUs and establish their optimal installation configuration, which can effectively improve the multiple MEMS-IMUs fusion accuracy for track irregularity measurement.

-

(2)

An AFKF is developed to fuse the multiple local MEMS-IMU information into the global filter, which can adaptive adjustment each MEMS-IMU sub-filters fusion factor and feedforward factor to obtain the highly estimation accuracy for track irregularity.

The organizational structure of this paper is arranged as follows: problem statement for track irregularity measurement is established in Sect. “Problem statement”; the proposed methodology is given in Sect. “Methodology”; Sect. “Experiments” the experimental investigation and result is discussion, followed by the conclusions in Sect. “Conclusions”.

Problem statement

As shown in Fig. 1, the MEMS-IMU is installed on the wheel of train, the measuring equation of track profile irregularity based on IMU can be expressed as:

where \(Y(t)\) and \(Z(t)\) denote the measurement of track irregularity in horizontal and vertical direction; \(a_{my}\) and \(a_{mz}\) represent the accelerometer measurements of MEMS-IMU in horizontal and vertical direction; \(\Delta a_{{g_{y} }}\) and \(\Delta a_{{g_{z} }}\) refer to the accelerometer measuring errors due to the different altitude of gravitational acceleration in horizontal and vertical direction; \(\omega_{my}\) and \(\omega_{mz}\) denote the angular velocity of IMU in horizontal and vertical direction.

Suppose the MEMS-IMU frame is denoted as \(\left\{ I \right\}\) and the globe frame is represented as \(\left\{ G \right\}\), then the measurements equation \(\left\{ {\omega_{m} ,a_{m} } \right\}\) of gyroscope and accelerometer can be expressed as:

where \({}^{I}\omega\) and \({}^{G}a\) denote the angular velocity and linear acceleration of MEMS-IMU in frame \(\left\{ I \right\}\) and \(\left\{ G \right\}\); \({}^{I}R_{G}\) represents the rotation matrix from \(\left\{ G \right\}\) to \(\left\{ I \right\}\); \(b_{g}\), \(b_{a}\) and \(n_{g}\), \(n_{a}\) denote the residual biases and white Gaussian noises of gyroscope and accelerometer; \({}^{G}g\) is the known gravity vector in frame \(\left\{ G \right\}\).

During the measuring of track irregularity, each MEMS-IMU maintains its own state, the following information will be shared include: speed, attitude, and positions with each other and update their own state independently. Normally, the whole system federated Kalman filter model is consisted of multiple MEMS-IMU motion state vector and built in a distributed structure. For the sake of computation efficiency, next we mainly illustrated the continuous-time motion state vector of one MEMS-IMU as Eq. (3), which includes three dimensional position state vectors, three dimensional velocity state vectors, attitude state vectors, the residual bias and scale factor errors of the gyroscope and accelerometer.

where \({}_{I}^{G} \dot{p}(t) = {}_{I}^{G} v(t)\) represents the MEMS-IMU position from frame \(\left\{ I \right\}\) to \(\left\{ G \right\}\); \({}_{I}^{G} \dot{v}(t) = {}_{I}^{G} a_{m} (t)\) denotes the MEMS-IMU velocity from frame \(\left\{ I \right\}\) to \(\left\{ G \right\}\); \(s_{g}\) and \(s_{a}\) refer to the residual scale factor errors of the gyroscope and accelerometer; \({}_{I}^{G} \dot{q}(t)\) is the quaternion rotation matrix from frame \(\left\{ I \right\}\) to \(\left\{ G \right\}\), which can be described as:

where \(\left\lfloor \cdot \right\rfloor\) denotes the skew-symmetric matrix.

According to the Eqs. (2) ~ (4), the output state model of MEMS-IMU can be expressed as:

Methodology

Installation of multiply MEMS-IMUs

Next, we will discuss the representative example of three MEMS-IMUs installation relationships, which also can be easily extended to the examples of multiply MEMS-IMUs. Figure 2 gives the installation relationships of three MEMS-IMUs, and the definition of globe frame \(\left\{ G \right\}\), IMU frame \(\left\{ {I_{1} ,I_{2} ,I_{3} } \right\}\). Generally, Fused the multiply MEMS-IMUs measuring information needs the knowledges of the installing relationships between the MEMS-IMUs. The installation relationship of multiple MEMS-IMUs is also called the geometric constraints, which will be detailed explained in the following:

Geometric constraints of multiple MEMS-IMUs

Normally, the measurement accuracy of track irregularity can be improved through the special geometric configuration of multiple MEMS-IMUs. To build the geometric constraints models of multiple MEMS-IMUs, it is necessary to analyze the geometric relationships among the multiple MEMS-IMUs sensitive axis and the coordinates frame. As shown in Fig. 3a, suppose that the multiple MEMS-IMUs is composed of n MEMS sensors in nonorthogonal way, the measuring state output of ith MEMS-IMU is expressed as:

where \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) denote the angle with the XY plane and Y axis.

According to the Eq. (6), the output equation of multiple MEMS-IMUs is computed as:

The Eq. (7) also can be abbreviated as:

where \(S = \left[ {s_{1} ,s_{2} , \cdots ,s_{n} } \right]^{T}\) denotes the measuring vector of multiple MEMS-IMUs; \({\rm K} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\cos \alpha_{1} \sin \beta_{1} } & {\cos \alpha_{1} \cos \beta_{1} } & {\sin \alpha_{1} } \\ {\cos \alpha_{2} \sin \beta_{2} } & {\cos \alpha_{2} \cos \beta_{2} } & {\sin \alpha_{2} } \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ {\cos \alpha_{n} \sin \beta_{n} } & {\cos \alpha_{n} \cos \beta_{n} } & {\sin \alpha_{n} } \\ \end{array} } \right]\) represents the multiple MEMS-IMUs measurement configuration matrix; \(L = \left[ {l_{x} ,l_{y} ,l_{z} } \right]^{T}\) denotes the angular rate of triaxial axes; \(\Psi = \left[ {\psi_{1} ,\psi_{2} , \cdots ,\psi_{n} } \right]^{T}\) represents the measurement noise of multiple MEMS-IMUs.

According to the Eq. (8), it can be seen that the geometric configuration of multiple MEMS-IMUs can be denoted by the installation matrix \(L\), it is necessary to estimate the optimal values of \(L\). Suppose the ith IMU measurement error can be expressed as:

where \(k_{i}\) refers to the ith row of \({\rm K}\); \(\hat{L}\) represents the estimate value of \(L\).

The objective function for multiple MEMS-IMUs geometric constraints can be constructed as:

According to the estimation criterion of least squares, the partial derivative of Eq. (10) can be calculated as:

By solving (11), the estimated outputs of multiple MEMS-IMUs can be obtained as

Generally, the measurement accuracy of multiple MEMS-IMUs can be enhanced by their geometric configuration, which can be denoted their installation matrix, suppose the estimation error matrix of \(\hat{L}\) is calculated as:

According to the Eq. (8), the Eq. (13) can be rewritten as:

The establishing process for geometric constrain model of multiple MEMS-IMUs requires firstly to estimate the minimum estimating errors for triaxial angular rates or accelerations. Therefore, an estimation equation can be expressed as

The covariance of the estimating errors \(\Omega\) is calculated as:

where \(\sigma\) denotes a predetermined value, also, the relationships between Eq. (15) and Eq. (16) can be expressed as:

where \(tr\left( \cdot \right)\) denotes the trace of matrix. Thus, obtaining the minimum values of the evaluating equation \(f_{e}\) is converted into solute the following function.

As shown in Fig. 3(b), assume \(tr\left( {K^{T} K} \right) = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{n} {\left\| {k_{i} } \right\|^{2} = n}\), and the eigenvalues of \(K^{T} K\) are \(\lambda_{1}\), \(\lambda_{2}\), \(\lambda_{3}\), then the singular value decomposition (SVD) of \(K\) can be expressed as:

With the left singular vector \(U = \left( {u_{1} , \cdots ,u_{n} } \right) \in R^{n}\), the right singular vector \(P = \left( {p_{1} ,p_{2} ,p_{3} } \right) \in R^{3}\), \(\Lambda = \left( {diag(\lambda_{1} ,\lambda_{2} ,\lambda_{3} ),0_{(n - 3) \times 3} } \right) \in R^{n \times 3}\). Then the Eq. (18) can be rewritten as:

Thus, the measuring accuracy of the multiple MEMS-IMUs formed by the optimal geometric configuration is the highest when \(\hat{f}_{e} = \frac{n}{3}I_{3 \times 3}\). Next, we will illustrate the representative geometric configuration for multiple MEMS-IMUs which satisfy the Eq. (20) with the number of MEMS-IMU \(n = 3,6,12\). As shown in Table 1, when the number of multiple MEMS-IMUs is \(n = 3,6,12\), the corresponding geometric configuration can be tetrahedron, hexahedron and dodecahedron, and the optimal geometric constraints will be satisfied the condition of Eq. (20) when their input axes are placed perpendicular to the surface of the corresponding configuration. The optimal configurations of measurement matrix K in each geometric configuration are descripted as (a) ~ (f), it can be seen that the measurement matrix K can provide the best measurement performance when satisfy the conditions \(\min_{K} tr\left( {\left( {K^{T} K} \right)^{ - 1} } \right) = \frac{n}{3}I_{3 \times 3}\), where the circle in (a) ~ (f) denotes the diagonal eigenvalue of \(K^{T} K\) in the same plane. Thus, as the number of MEMS-IMU is satisfied the Eq. (20), the optimal measurement accuracy of multiple MEMS-IMUs can be obtained.

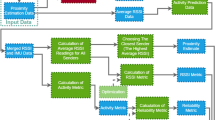

Information fusion of multiple MEMS-IMUs

Normally, the traditional federal Kalman filter (FKF) can be used to fuse the multiple local sensors information into one global system with a fixed filter structure. Whereas, as the local sensors layout is changed and the used filter structure is not adjusted in time, which will lead to the low fusion accuracy and poor fault tolerances during multiple local sensors integration. To solve the above problems, we propose an adaptive filter structure named AFKF as shown in Fig. 4, it mainly includes traditional Kalman Filter, information fusion factor, information feedforward factor. During the process of AFKF, the adaptive feedforward and feedforward factor can give the adaptive control for sub-filters, thereby the estimating accuracy and fault tolerances of AFKF have been improved.

Traditional federated Kalman filtering model

According to the Reference27, suppose the time updating course for each MEMS-IMU filter is proceeded independently, the state equation of the ith MEMS-IMU is expressed as:

where \(Z_{k}^{i}\) denotes the \(m \times 1\) measurement value, \(H_{k}^{i}\) represents the \(m \times n\) measurement matrix; \(X_{k}^{i}\) denotes the \(n \times 1\) state estimate of MEMS-IMU; \(V_{k}^{i}\) represents the measurement noise matrix.

Normally, the traditional FKF concludes a composite master filter and n independent local filters, its implementation steps are expressed as:

Information distribution

The information distribution is referred to estimate the global optimal value \(\hat{X}_{k}^{i}\), error covariance matrix \(P_{k}^{i}\) and system noise covariance matrix \(Q_{k}^{i}\) to each sub-filter through the information sharing factor \(\gamma_{i}\) as:

where the symbol with superscript “g” denotes the global filter; \(\gamma_{i} > 0\) satisfies following information conservation principle: \(\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{n} {(\gamma_{i} )} + \gamma_{m} = 1\).

Time updating

The process of time updating for each MEMS-IMU filter is performed independently, then their own prior predicting state and error covariance matrix can be expressed as:

where \(P_{k - 1}^{i}\) is the posterior error covariance matrix of the ith filter at time k-1.

Measurement updating

The measuring updating refers to the posterior predicting for their states and error covariances. Based on the observation values of prior state estimation and error covariances, the posterior state estimation and error covariances can be written as:

where \(P_{k}^{i}\) refers to the posterior error covariance matrix of the ith filter at time k, \(R_{k}^{i}\) denotes the covariance matrix of \(V_{k}^{i}\); \(H_{k}^{i}\) represents measurement matrix of the ith filter at time k.

Information fusion

According to the Eq. (24), the global optimal estimation for multiple MEMS-IMUs is expressed as:

Adaptive federated Kalman filter

Adaptive feedforward factor

Generally, the traditional FKF global fusion strategy can be acquired through local filter’s combination, while it cannot obtain the feedforward information during the fusion process of multiple local filters. Therefore, we design an adaptive feedforward factor to obtain the feedforward fusion information for each sub-filter. The designed adaptive feedforward factor can be expressed as:

where d denotes a designed constant; \(\Delta \tilde{e}_{k}^{i}\) represents the standardized estimation residuals of ith sub-filter at time k, it can be expressed as:

where \(\Delta \tilde{e}_{k}^{i}\) denotes the residual of ith sub-filter at time k, it also refers s to the errors between the actual values and predicted values;\(H_{k}^{i} P_{k}^{i} (H_{k}^{i} )^{T} + R_{k}^{i}\) represents the error covariance matrix of theoretical values and predicted values.

Based on the Eqs. (25) and (26), The global fusion for multiple MEMS-IMUs can be expressed as:

Adaptive feedback factor

During the fusion process of sub-filter, the global filter requires to feedback the fusion information for each sub-filter. However, the traditional FKF algorithm usually designs the feedback factor as a constant value, which cannot exhibit the accurate performances changing or corresponding sub-filter. For this reason, we design an adaptive feedback distribution factor by using the sub-filters real-time error covariance matrix changed to decrease the influences of improper distribution, which can be computed as:

where \(P_{i,k}\) denotes the posterior error covariance matrix of the ith filter at time k.

Combining with the Eqs. (28) and (29), the final output results of multiple MEMS-IMUs information fusion can be written as:

According to the Eq. (30), in the process of information fusion of multiple MEMS-IMUs, the proposed AFKF with an adaptive feedforward and feedforward factor can effectively improve the estimating accuracy of the state vector \(\hat{X}\) of multiple MEMS-IMUs system in Eq. (3). Then the measurement accuracy of angular and accelerometer \(\left\{ {\omega_{m} ,a_{m} } \right\}\) in Eq. (2) will also be improved by \(\hat{X}\). Thus, combining the Eqs. (1)–(3) and Eq. (30), it can be seen that the output values of track irregularities \(\left( {Y(t),Z(t)} \right)\) can be achieved the highly measurement accuracy in horizontal and vertical direction.

Experiments

To demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed method, a series of experiments were conducted in both laboratory and field environments, also the proposed method has been compared with high-precision fiber optical IMU method, which was already use for track irregularity measurement.

Laboratory environmental experiments

As shown in Fig. 5, the laboratory environmental experiments were proceeding on the 6-DOF track irregularity comprehensive test platform, which could simulate different track irregularity conditions and provide the actual displacements in horizontal and vertical direction, its displacement accuracies in horizontal and vertical direction can reach 0.05 mm. In this experiment, two measurement configurations are used to evaluate the performances of track irregularity, which are our proposed multiple MEMS-IMU and single high-precision fiber-optical IMU, and their specifications are given in Table 2.

In the experiments, three MEMS-IMUs were mounted on three different positions of the 6-DOF platform following the designed geometric configuration, and the single fiber-optical IMU was approximately installed on the platform center, also a battery module was used for power supply and a Bluetooth module was applied for time synchronization. Take the left track as an example. Firstly, sinusoidal signal (with amplitude ± 5 mm) of the compound motion attitude is input to the 6-DOF platform to simulate different left track irregularity conditions. Secondly, we used the proposed method and fiber-optical IMU to measure the left track irregularity simultaneously, also the standard deviation (STD) root-mean-square error (RMSE) was commonly applied to evaluate the left track irregularity measuring accuracy, where a smaller RMSE value denotes the higher accuracy. Specifically, the RMSE denotes the sum of the squares of the deviation between the measurement values and true values. The best value then refers to the track irregularity results. Otherwise, to effectively reflect the measurement left track irregularities, we conducted five different left track irregularity measurement experiments, also each track mission would be independently measured four times. The measurement results of left track irregularity in horizontal and vertical direction are given in Table 3.

It can be seen from the Table 3 and Fig. 6 that the maximum, minimum and mean values of RMSE and STD in horizontal direction using our proposed method and single MEMS-IMU are (0.91 mm, 0.76 mm, 0.83 mm)RMSE, (0.69 mm, 0.56 mm, 0.62 mm)STD and (1.42 mm, 1.23 mm, 1.32 mm)RMSE, (1.07 mm, 0.98 mm, 1.02 mm)STD, respectively. While the corresponding measuring results in vertical direction are even better, which are (0.89 mm, 0.75 mm, 0.81 mm)RMSE, (0.65 mm, 0.54 mm, 0.59 mm)STD and (1.39 mm, 1.21 mm, 1.28 mm), (1.05 mm, 0.96 mm, 1.01 mm), respectively. As for the fiber-optical IMU measurement method, the maximum, minimum and mean values of RMSE and SD in horizontal direction are 0.78 mm, 0.63 mm, 0.71 mm and 0.56 mm, 0.44 mm, 0.49 mm, and in vertical direction are0.76 mm, 0.61 mm, 0.68 mm and 0.54 mm, 0.42 mm, 0.47 mm, respectively. Compared with the fiber-optical IMU measurement method, the measuring accuracy of track irregularity based on our proposed method is very close to the fiber-optical IMU method, while has a great improvement contrast to single MEMS-IMU method. Otherwise, compared to using the fiber-optical IMU with expensive, larger size and heavy weight, our proposed method has comparable measurement accuracy yet with low-cost and small size.

Field environmental experiments

To verify the proposed track irregularity measurement method, we also conducted the field test on a circular heavy haul railway with different speeds at China National Railway Test Center. Figure 7 shows the layout of the experimental setup in field environment, which included four MEMS-IMUs (Three MEMS-IMUs used for experimental analysis and one MEMS-IMU served as supplement) were separately installed on the train left and right wheel centers, two MEMS-IMUs were mounted on the centers of front and back bogie platform, also one fiber-optical IMU and the other sensors were fixed on the train cabin. In order to fully verify our proposed method, four independent groups of tests were runed over the same track section.

Take the left track as an example. Since the same track segment was measured four times, the left track irregularity can be denoted as comparing the difference between the four measurements, which are marked as M21, M31, M41, M32, M42 and M43 (for example, M21 represents the difference between M2 and M1, et al.). The comparation results of left track irregularity in horizontal and vertical direction are given in Table 3 (with 60 km/h) and Table 4 (with 100 km/h).

For the train speed with 60 km/h, it can be found in the Table 4 that the maximum, minimum and mean values of RMSE and STD in horizontal direction using our proposed method are 0.56 mm, 0.47 mm, 0.49mmand 0.45 mm, 0.37 mm, 0.41 mm; and in the vertical direction, which are0.55 mm, 0.45 mm, 0.48 mm and 0.44 mm, 0.36 mm, 0.40 mm,respectively.As for the fiber-optical IMU, the corresponding values of maximum, minimum and mean values of RMSE and SD in horizontal direction are 0.47 mm, 0.41 mm, 0.43 mm and 0.39 mm, 0.35 mm, 0.37 mm; and in the vertical direction, which are0.46 mm, 0.40 mm, 0.42 mm and 0.38 mm, 0.34 mm, 0.35 mm,respectively.Similarity, For the train speed with 100 km/h in the Table 5, the MSER and STD maximum, minimum and mean values in horizontal direction using our proposed method are 0.58 mm, 0.48 mm, 0.52mmand 0.47 mm, 0.39 mm, 0.43 mm; and in the vertical direction, which are0.57 mm, 0.47 mm, 0.51 mm and0.46 mm, 0.38 mm, 0.42 mm. As for the fiber-optical IMU, the corresponding values of maximum, minimum and mean values of RMSE and SD in horizontal direction are 0.49 mm, 0.43 mm, 0.45 mm and 0.41 mm, 0.37 mm, 0.39 mm; and in the vertical direction, which are0.48 mm, 0.42 mm, 0.44 mm and 0.40 mm, 0.36 mm, 0.38 mm, respectively.

According to the above mentioned, it also proved that our proposed method is very close to the fiber-optical IMU method in field environments.

Conclusions

In order to address the challenges faced by low-cost MEMS-IMU in providing high-precision track irregularity measurement information, we propose an accurate measurement method for track irregularity that combines the multiple IMUs and geometric constraints, which is able to obtain noticeable performance gain without incurring additional computational cost. To achieve this, we first construct the geometric constraint models for multiple IMUs and establish their optimal installation configuration. Subsequently, an adaptive federal Kalman filter is developed to fuse the multiple local IMUs information into the global filter, which can adaptive adjustment each IMU sub-filters fusion factor and feedforward factor to obtain the highly estimation accuracy for track irregularity.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due [REASON WHY DATA ARE NOT PUBLIC] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, Y., Tang, H., Wang, P., Liu, X. & Chen, R. Multipoint chord reference system for track irregularity: Part I-theory and methodology. Measurement 138, 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2019.01.080 (2019).

Mi, J., Wang, Q., Liu, P. & Han, X. A performance enhancement method for redundant IMU based on neural network and geometric constraint. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 73, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2024.3368485 (2024).

Ji, C. et al. A novel method for the general application of measured load spectra to different high-speed train bogie frames based on virtual track irregularity. Measurement 198, 111369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111369 (2022).

Zhang, M., Xu, X., Chen, Y. & Li, M. A lightweight and accurate localization algorithm using multiple inertial measurement units. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 5(2), 1508–1515. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2020.2969146 (2020).

Niu, X., Wu, Y. & Kuang, J. Wheel-INS: A wheel-mounted MEMS IMU-based dead reckoning system. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 70(10), 9814–9825. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2020.2969146 (2021).

Chen, Q., Niu, X., Zhang, Q. & Cheng, Y. Railway track irregularity measuring by GNSS/INS integration. Navig. J. Inst. Navig. 62(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/navi.78 (2015).

Chen, Q. et al. Semi-analytical assessment of the relative accuracy of the GNSS/INS in railway track irregularity measurements. Satell. Navig. 2, 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43020-021-00057-9 (2021).

Zhu, F., Luo, K. & Zhou, W. Measuring railway track irregularities at high accuracy and efficiency based on GNSS/INS/TS integration. IEEE Sens. J. 22(15), 15334–15344. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2022.3183433 (2022).

Zhu, F. et al. Attitude variometric approach using DGNSS/INS integration to detect deformation in railway track irregularity measuring. J. Geod. 93, 1571–1587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-019-01270-w (2019).

Gao, Z. et al. Railway irregularity measuring using Rauch–Tung–Striebel smoothed multi-sensors fusion system: quad-GNSS PPP, IMU, odometer, and track gauge. GPS Solut. 22, 36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-018-0702-5 (2018).

Wu, Y., Kuang, J. & Niu, X. Wheel-INS2: multiple MEMS IMU-based dead reckoning system with different configurations for wheeled robots. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 24(3), 3064–3077. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2022.3220508 (2023).

Shen, Q., Yang, D., Li, J. & Chang, H. Bias accuracy maintenance under unknown disturbances by multiple homogeneous MEMS gyroscopes fusion. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 70(3), 3178–3187. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2022.3167137 (2023).

Shen, C. et al. Seamless GPS/inertial navigation system based on self-learning square-root cubature kalman filter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 68(1), 499–508. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2020.2967671 (2021).

Libero, Y. & Klein, I. Augmented virtual filter for multiple IMU navigation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 73, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2024.3370767 (2024).

Sahu, N., Babu, P., Kumar, A. & Bahl, R. A novel algorithm for optimal placement of multiple inertial sensors to improve the sensing accuracy. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 68, 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2019.2957639 (2020).

Zhu, M., Yu, F., Xiao, S., Fan, S. & Wang, Z. An improved posteriori variance-covariance components estimation applied to unconventional GPS and multiple low-cost IMUs integration strategy. IEEE Access 7, 136892–136906. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2941996 (2019).

Guo, F. & Wang, P. Measurement and analysis of the longitudinal level irregularity of the track beam in monorail tour-transit systems. Sci. Rep. 12, 19219. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23805-6 (2022).

Larey, A., Akin, E. & Klein, I. Multiple inertial measurement units–an empirical study. IEEE Access 8, 75656–75665. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2988601 (2020).

Sun, X., Yang, F., Shi, J., Ke, Z. & Zhou, Y. On-board detection of longitudinal track irregularity via axle box acceleration in HSR. IEEE Access 9, 14025–14037. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3052099 (2021).

Muñoz, S., Ros, J., Urda, P. & Escalona, J. L. Estimation of lateral track irregularity through kalman filtering techniques. IEEE Access 9, 60010–60025. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3073606 (2021).

Guo, X., Li, C., Luo, Z. & Cao, D. Identification of track irregularities with the multi-sensor acceleration measurements of vehicle dynamic responses. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 62(4), 906–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/00423114.2023.2200193 (2023).

Chen, Q., Zhou, Y., Fang, B., Zhang, Q. & Niu, X. Experimental study on the potential of vehicle’s attitude response to railway track irregularity in precise train localization. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 23(11), 20452–20463. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2022.3174884 (2022).

Niu, X., Wu, Y. & Kuang, J. Wheel-INS: A wheel-mounted MEMS IMU-based dead reckoning system. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 70(10), 9814–9825. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2021.3108008 (2021).

Shen, K., Wang, M., Fu, M., Yang, Y. & Yin, Z. Observability analysis and adaptive information fusion for integrated navigation of unmanned ground vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 67(9), 7659–7668. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2019.2946564 (2020).

Xu, X. et al. An indoor mobile robot positioning algorithm based on adaptive federated kalman filter. IEEE Sens. J. 21(20), 23098–23107. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2021.3106301 (2021).

Huang, H., Zhang, H. & Jiang, L. An optimal fusion method of multiple inertial measurement units based on measurement noise variance estimation. IEEE Sens. J. 23(3), 2693–2706. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2022.3229475 (2023).

Ayabakan, T. & Kerestecioglu, F. Fault tolerant indoor positioning based on federated Kalman filter. J. Signal Process. Syst. 96, 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11265-024-01913-y (2024).

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52278465, 52272427), Science and Technology Research and Development Plan of China Railway (Grant No. N2022G051, K2022T006), and Key Project of China Academy of Railway Sciences (Grant No. 2023YJ024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yan Wang: methodology, program, writing. Shibin Wei: project administration, methodology. Lin Li: investigation, program. Jiyou Fei: investigation, supervision. Fei Yang: data acquisition, experiment. Peng Dai: validation, experiment.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Wei, S., Li, L. et al. Novel method to measure track irregularity based on multiple MEMS-IMU and geometric constraint. Sci Rep 15, 8717 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93151-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93151-w