Abstract

Figs are delectable, beneficial, nutritious, and seasonal; nevertheless, they deteriorate quickly, making processing the optimal method for preservation. Drying figs is the most practical and efficient way to preserve them. Paste is another possibility. The present study emphasizes the nutritional value of two fig pastes, as well as their antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Ghoudane (GD) and Chetoui (CH) fig pastes are high in sugars, fiber, minerals, and antioxidants, making them nutritious. The HPLC-UV-MS/MS analysis identified bioactive compounds of the two fig pastes under investigation. The CH paste was found mainly to contain gallic acid, quercetin, 3’-methyl ether, and neochlorogenic acid. Similarly, the GD paste notably comprises catechin, 3’-methyl ether, and neochlorogenic acid. GD paste has more polyphenols (374.6 ± 4.57 mg GAE/100 g) and flavonoids (102.5 ± 2.16 mg QE/100 g) than CH paste. The GD paste was shown a strong antioxidant, as shown by its DPPH IC50 value of 5.62 ± 0.02 mg/mL and TAC value of 80.16 ± 0.83 µg AAE /mg extract. Also, it revealed a strong correlation between the contents of bioactive polyphenols and flavonoids and their antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Furthermore, hydroethanol fig paste extracts have shown high antibacterial and fungal activity. In silico analysis showed that the bioactive chemicals in both pastes demonstrated different levels of inhibition against the targeted proteins. The quercetin 3-methyl ether demonstrated the highest efficacy in blocking NADPH oxidase, with a glide gscore of -6.307 K/mol. On the other hand, neochlorogenic acid exhibited the highest efficacy in inhibiting the activity of two enzymes: diphosphate kinase from Staphylococcus aureus (-10.493 kcal/mol) and β-ketoacyl-[acyl carrier protein] synthase from Escherichia coli (-7.357 kcal/mol). Catechin is highly potent in inhibiting the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans by targeting sterol 14-α demethylase (CYP51) with a glide gscore of -7.638 kcal/mol. The fig paste is an important source of nutrients and biologically active substances that can be used in several fields, such as food and phytopharmaceuticals. This confirms the importance of the fig paste process as a way of increasing the value of the fig fruit, enhancing its utility, and thereby increasing its reputation and appreciation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The fig (Ficus carica L.) fruit is typically consumed locally fresh or in dried, canned, or preserved form. Dried figs, including those that are unfit for human consumption, can be used as animal feed1,2. Several countries import dried figs or paste. Turkey and the United States are the leading exporters of dried figs and paste1,2. Plants’ ability to create a wide range of natural chemicals is one of their most unique characteristics. Secondary metabolites, which may not have evident physiological functions, are valuable chemicals used in disciplines such as pharmaceuticals and the agri-food industry3. Most of the figs produced are consumed in their fresh form. Therefore, it is crucial to select cultivars that have the desired qualities for consuming fresh fruit, such as an adequate fruity taste, an ideal balance between sweetness and acidity, and an excellent ability to withstand post-harvest conditions4. Based on data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), dried figs have the highest nutrient score among all dried fruits due to their significant contribution of vitamins and minerals. Fig is rich in iron, proteins, calories, and fiber. It has higher calcium content than milk. The fig has a nutritional value of 11, while the date, raisin, and apple have nutritive indices of 6, 8, and 9, respectively5. Polyphenols are secondary metabolites that are mostly found in plant tissues. They are produced through the shikimic acid and phenylpropanoid pathways6. These polyhydroxy phytochemicals are aromatic molecules that have at least one phenol group in their structure. They are the most common secondary metabolites found in plants, with over 8000 known structures7. Phenolic substances are categorized into different subclasses, such as flavonoids, phenolic acids, coumarins, curcuminoids, quinones, tannins, lignans, and stilbenes, based on their chemical structures6.

The pulp and peels of various fig cultivars contain several bioactive compounds, including ferulic acid, 3-O- and neochlorogenic acids, quercetin-3-O-glucoside, quercetin-3-O-rutinoside, psoralen, bergaptenn, gallic acid, syringic acid, catechin, epicatechin, luteolin, 6 C-hexose-8 C-pentose, and apigenin-rutinoside. These antioxidants have important pharmacological and health effects8,9,10. Polyphenolics have recently received a lot of attention in the scientific world, prompting various investigations on these compounds. According to research, ingesting beverages and foods high in phenolic content can reduce the risk of heart disease by acting as antioxidants against low-density lipoprotein11. Figs were found to have a high total lipid content compared to other fruits such as apples, grapes, and citrus fruits. This can be explained by the fact that figs contain a large number of small, oil-rich seeds12. One of the attractive parts of the whole fig, which influences both its nutritional value and health effects, is its seeds. The inner part of the fig is a white skin containing a seed mass bound by jelly-like flesh13. Fig seeds vary greatly in size, being large, medium, small, or minute, and their number ranges from 30 to 1600 per fruit13,14. There are many edible seeds in a fig, and they are usually hollow unless they have been pollinated. The characteristic nutty flavor of dried figs comes from the seeds. Nowadays, fig seeds can be used as a source of edible oil and lubricant13. The less studied part of the fig fruit is the seed, which contains oil, fatty acids, phenolic, and antioxidant properties15,16. Fig seeds contain yellow-colored oil ranging from 21.5 to 28.5%. Fig seed oil is also rich in nutrients such as carbohydrates, calcium (Ca), potassium (K), and phosphorus (P). In addition, they have higher amounts of unsaturated fatty acids such as alpha-linolenic acid (26.3%), linoleic acid (24.2%), and oleic acid (19.6%) as determined by gas chromatography/mass spectrophotometry (GC/MS) analysis compared to saturated fatty acids such as palmitic acid ranging from 8.54 to 9.05% and stearic acid ranging from 2.59–3.3%15. The antioxidant capacity was 140.1 mg/TE/100 g. It also contains 314.6 mg/100 g of γ-tocopherol15. This fig seed oil could be used as a supplement in the treatment of diseases such as cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disorders, and diabetes. As fig seeds are too small to chew or eat, they cannot be used as a beneficial food source. They are indigestible and are usually eliminated from the body in the feces17.

The bioactivities of polyphenolics have been the subject of substantial scientific inquiry. These studies have revealed a wide spectrum of polyphenolic properties, including antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antiproliferative activity18. Researchers and food manufacturers are increasingly interested in the antioxidant capabilities of phenolics and their possible involvement in preventing numerous disorders related to oxidative stress7. The trend of investigating natural sources of antioxidants has gained traction, especially due to the removal of synthetic antioxidants in food applications. Recently, nutritionists have focused on studying the nutritional and physiological advantages of polyphenols. They have acknowledged that polyphenols can affect oxidative stability, color, bitterness, odor, astringency, and flavor6. Scientists have extensively studied natural antioxidant molecules because of their promise in treating conditions related to oxidative stress. Furthermore, their biological qualities, specifically their antimicrobial qualities, make them valuable assets in the food business19. The incorporation of chemical structures from different medications into plant derivatives provides a valid explanation for the evident resurgence in the application of plant-based medicine. Traditional medicine is the predominant healthcare approach utilized by 80% of the global population in Africa. The majority of conventional medicines utilize plant extracts or their active constituents20. The rise of germ resistance to current antibiotics, along with the negative impacts of modern medications and the limited availability of antibiotics in the pipeline, has emphasized the significance of discovering novel antimicrobial medications. As a result, scientists have shifted their focus toward studying the antimicrobial characteristics of medicinal plants21,22.

Chetoui and ghoudane fig varieties have been selected in eastern Morocco because of their extensive distribution and commercial value. These two local fig varieties belong to the common fig type, and the chetoui (CH) variety is a uniferous fig tree that produces solely parthenocarpic autumn figs, which are also known as “karmos.” In contrast, the ghoudane (GD) variety has biferous characteristics, producing parthenocarpic flower figs known as “Bakor” in the spring and parthenocarpic “karmos” figs throughout the autumn. From an agri-food standpoint, as a summer fruit, these two fresh figs have an excellent taste; they are sought after and appreciated by consumers not only because of their outstanding quality but also because of their favorable pomological parameters. The autumn fig skin color of CH is green with purple spots (Fig. 1), while GD is black (Fig. 2); these two varieties can be enjoyed fresh or dried23.

In eastern Morocco, the fig tree is an important fruit tree. The annual “Aghbal fig festival” in Ahfir, the region’s main fig producer, is a celebration of the fruit. This event recognizes the economic and socio-cultural importance of the fig tree and its products. As drying ovens are not readily available in the eastern region of Morocco, farmers and the general public often rely on the sun to dry CH and GD figs. The second option is the production of fig paste. Both initiatives have the same goal: to increase the opportunity to enjoy the benefits of this prized fruit, to manage the market for fresh figs, and to maximize economic benefits. Figs are widely consumed fresh in the eastern region of Morocco, largely due to their high nutritional value, appealing flavor, and relatively short shelf life. Furthermore, it is important to emphasize the importance of using the fig paste conversion process in order to appreciate and adapt the offering of this blessed fruit in this region.

There has been no previous research in this area on the composition, characteristics, nutritional, and biological components of CH and GD pastes, nor has it examined their antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. This study seeks to illustrate that fig pastes serve as a significant source of nutritional and specific bioactive substances for application in food and phytopharmaceuticals, while also affirming that their utilization can augment the value of fig fruit, so elevating its reputation and esteem. In order to ascertain the nutritional value and benefits of the two fig pastes under consideration, as well as to confirm their similarities or differences, it was necessary to use traditional analytical techniques. In addition to this, HPLC-UV/MS/MS was used to qualitatively define their bioactive components and to evaluate their antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. The in silico method was employed to validate and ascertain the participation of the bioactive components found in the examined fig paste extracts in antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Additionally, it aimed to elucidate the mechanisms by which some of these biologically active substances function in these specific antioxidant and antimicrobial applications.

Materials and methods

Sampling and preparation of fig pastes

The current study focused on the pastes of two dried fig varieties: Chetoui (CH) and Ghoudane (GD), using the local vernacular name given by the farmer to the crop and variety. The identification of the plant was done by the professional botanist, Professor Fennane Mohammed from Scientific Institute in Rabat, Morocco, where a voucher specimen of the plant is deposited at the plant section of Herbarium University Mohammed Premier Oujda (HUMPO 100) Morocco. These adult trees in farmers’ traditional orchards are approximately the same age of twelve years in the four study locations in Aghbal, near the town of Ahfir (Fig. 3).

Fig fruit was inspected and sampled from the most mature, healthy, disease-free basal fruit collected at mid-ripening according to the fig descriptors24. Samples were taken at random, and an attempt was made during collection to remove the influence of exposure by taking the same three fruits from all cardinal points: north, south, east, and west. Samples of 240 fresh figs (twelve fruits per tree and five trees per variety in each location) were collected and immediately taken to the laboratory, mixed, and then rinsed with drinking water to remove contaminants.

The fig fruit is steamed in a thermic fluid steel-jacketed kettle at 100 °C for 20 min to soften the fig fruit. Boiling allows soluble fibers to dissolve. The cooked fruits are ground in a fruit grinder, then we crush them in a fruit pulper and press them until the result is a smooth and homogenous paste. The final product is separated into four 100 g aliquots for each variety, which are then packaged into glass bottles intended for storage at 20 °C.

Process of extracting

The extraction from different pastes was achieved by macerating them in a process called “solid-liquid extraction” using 95% ethanol. After blending 30 g of finely ground fig paste with 300 mL of the extraction solvent, the mixture was soaked in the dark at 20 °C for 24 h with occasional stirring. After passing through a filter paper of Whatman n◦1, the liquid extracts were immediately examined to determine the quantities of the bioactive compounds being studied, as well as their antioxidant characteristics25. In addition, the following parameters are also measured: pH, titratable acidity (expressed as a percentage of citric acid), vitamin C content (measured in mg per 100 g), conductivity (measured in mS. m−1), soluble solids content (measured in °Brix), and total sugar content (expressed as a %). The solvent in the fig paste extract was removed through evaporation at a temperature of 45 °C using a BÜCHI type rotary evaporator under vacuum conditions. This process resulted in the formation of a dried residue, which was then used to investigate the antimicrobial activity. The extraction efficiency (EE) is calculated by the following formula:

EE: Extraction efficiency in %;

Mext: Mass of extract after evaporation of solvent in mg;

Mpm: Mass of initial plant material (dry weight) in mg.

EE = 15.2% for CH paste, while EE = 15.9% for GD paste.

The process parameters (nature and preparation of the material to be extracted, chemical structure of the phenolic compounds, extraction time, solid/liquid ratio, extraction method used, and possible presence of interfering substances.) influence the extraction efficiency. However, the solvent and the temperature generally have the greatest influence on the efficiency of the extraction of bioactive compounds from plant material26. It is generally known that alcohol/water solutions have a better influence on the extractability of phenolic compounds compared to the mono-component solvents. As the phenolic compounds of different plants differ structurally, it is difficult to develop a standardized extraction method that would simultaneously extract all the inherent phenolic compounds26.

Assessment of the physicochemical parameters of fig pastes

Moisture, ash and organic matter of fig paste

The moisture content was measured by subjecting 5 g of fig paste to the drying oven (Daihan Labtech Co., Ltd., MODEL LDO-150 N, Indonesia) in intact capsules for 2 h at a temperature of 103 ± 2 °C. The capsules were subsequently cooled in a desiccator before being weighed, and this procedure was repeated until a stable weight was achieved27.

5 g of the sample were burned for three to 5 h at 550 °C in a muffle furnace (STUARTSCIENTIFIC CO. LTD. FURNACE, Great Britain) to determine the amount of ash or minerals present28. The crucibles were then allowed to cool in a desiccator and weighed repeatedly until a consistent weight was reached. It was said that the finished product was white or greyish-white in color28,29. After calcination, the percentage of total organic matter is determined. Organic matter is responsible for the observed mass loss.

Analysis of fig paste’s pH, titratable acidity, total soluble solids, and conductivity

It should be noted that all of the aforementioned analytical methodologies were executed in triplicate. To measure pH, 5 g of sample were added to 50 mL of distilled water in a beaker. The mixture was cooked in a 70 °C water bath (Memmert D-91126 Schwabach FRG, Germany) for 1 h, stirring occasionally with a spatula30. The mixture was ground in a mortar, and it was ensured that the electrode was immersed in the resulting solution prior to the reading of its pH value. The AFNOR method (NF V O5 − 101, 1970) was utilized to test the titratable acidity, expressed as a % of citric acid. The procedure entailed the titration of a 0.1 N sodium hydroxide solution until the phenolphthalein indicator exhibited a pink coloration for 30 s, thus indicating an increase in pH to 8.123. The quantification of soluble solids content (Brix) was accomplished through the utilization of a digital refractometer (HANNA NUMERIQUE HI 96801-ECHELLE 0–85% BRIX, France)30. The measurement of conductivity was undertaken using a solution comprising 20% solids from the paste figs. Thereafter, the conductivity meter’s electrode was immersed directly into the solution. The resulting reading was obtained immediately from the conductivity meter’s (C833, Consort, Turnhout, Belgium) display31.

Examination of Fig Paste’s macronutritional and vitamin C

These chemical assays were performed in triplicate. Dubois et al.‘s colorimetric method was used to determine the total sugar composition of fig paste32. The Weende method, first published by Henneberg and Stohmann in 1859, was used to determine the crude fiber content. This procedure involved treating the sample with sulfuric acid and potash in that order33. The AFNOR technique (1982) was used to analyze the lipid content, as stated in NF EN ISO 734-1(2000). The Soxhlet device was used to extract hexane from paste fig sample34. While, the Kjeldhal method35was used to measure the protein content. The quantity of ascorbic acid was ascertained through the following procedure. 1 g of the fig paste was combined with 10 mL of oxalic acid (1%) and stirred for 15 min. Thereafter, the mixture was filtered and 3 mL of the filtrate was mixed with 1 mL of 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) (5 mM). Following this, the mixture’s absorbances were measured at 515 nm after 15 s. This procedure enabled the concentrations of ascorbic acid (AA) – expressed in mg of AA per 100 g of dry matter – to be estimated25.

Total polyphenols content determination in the fig paste

The Folin-Ciocalteu (FC) method was used to determine the total polyphenol content (TPC). 100 µL extract is mixed with 500 µL FC reagent and 400 µL of 7.5% (w/v) Na2CO3. The mixture is stirred and incubated in the dark at 20 °C for ten minutes, and then the absorbance is measured at 760 nm. The values are then expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per g of dry fig paste, with the gallic acid calibration curve serving as a reference36. The TPC was calculated by using the calibration curve obtained as y = 4.96 x + 0.29 with R2 = 0.99.

The total flavonoid content determination in the fig paste extracts

The AlCl3 method was employed to determine the total flavonoid content (TFC). To do the test, we mixed 500 µL of each extract with 1500 µL of 95% methanol, 100 µL of 10% (m/v) AlCl3, 100 µL of 1 M sodium acetate, and 2.8 mL of distilled water. For 30 min, the mixture is mixed and incubated in the dark at room temperature. The blank is formed by replacing the extract with 95% methanol, and the absorbance at 415 nm is measured. The results of the quercetin calibration curve are expressed as the quercetin equivalent (QE) in mg per g of dried fig paste37. The TFC was calculated by using the calibration curve obtained as y = 6.21 x + 0.20 with R2 = 0.98.

HPLC- UV-MS/MS analysis of fig paste extracts

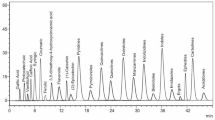

Phenolic compounds were analyzed qualitatively using HPLC-UV-MS/MS analysis with a liquid chromatography system coupled with a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA). We used a Kinetex C18 reversed-phase column (100 × 4.6 mm, 2.6 μm particles) to separate solvent A (0.1% formic acid aqueous solution) and solvent B (methanol), as described in the study of Bouaouda et al. (2023)38: 0–3 min, linear gradient from 5 to 25% B; 3–6 min, at 25% B; 6–9 min, from 25 to 37% B; 9–13 min, at 37% B; 13–18 min, from 37 to 54% B; 18–22 min, at 54% B; 22–26 min, from 54 to 95% B; 26–29 min, at 95% B; 29–29.15 min, going back to initial conditions at 5% B; and re-stabilizing the column from 29.15 min to 31 min to the initial gradient 5% B. Standard was analyzed under the same conditions. The identification of phenolic compounds relied on comparing retention times and mass spectra with those of standards, as well as referencing the NIST-MS/MS library.

Antioxidant activity determination of fig paste extracts

Total antioxidant capacity

The total antioxidant capacity was assessed using the phosphor-molybdenum method, as outlined in the references39,40,41. The standard/extract solution, measuring 0.1 mL, was mixed with a reagent solution containing 0.6 M sulfuric acid, 28 mM sodium phosphate, and 4 mM ammonium molybdate. The mixture was then incubated at a temperature of 95 °C for 90 min. The solution was allowed to cool to the temperature of the surrounding environment, and the level of light absorption at a wavelength of 695 nm was determined. Except for the test sample, the blank solution included all of the reagents. A standard curve was generated utilizing ascorbic acid. The results were expressed in terms of ascorbic acid equivalents (AAE)42.

DPPH radical scavenging assay

To estimate antioxidant activity, the fig paste extract’s DPPH (2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazil) radical scavenging capacity was used. The extract’s IC50 value represents the concentration required to reduce DPPH by 50%. Lower IC50values indicate high scavenging activity. Different concentrations of each extract and ascorbic acid standard were generated. Each concentration of extract or standard was added to 2.5 mL of the prepared DPPH ethanol solution (2 mg DPPH/100 mL ethanol) to make a final volume of 3 mL. After 30 min at 20 °C, absorbance at 515 nm was measured against a control (all reagents except the extract or standard)30. Using the following formula, the DPPH free radical scavenging activity was estimated in percentage (%):

$${\rm [A] (Sample) = [A] (fresh\: or\: dried\: extract\; or\; standard\; at\; different\; concentrations)}$$The IC50 values were found using GraphPad Prism 8 to make a curve of the antioxidant concentration (mg/mL) versus inhibition.

Antimicrobial activity assay of fig paste extracts

Five different microorganisms were employed in this experiment. There were two types of Gram-negative bacteria in the group: Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853); two types of Gram-positive bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923) and Bacillus subtilis subsp. spizizenii (ATCC 6633); and one type of pure fungus, Candida albicans. These microorganisms were cultivated at + 4 °C on Biorad’s Muller-Hinton agar (MH) to facilitate their growth. Every two weeks, the cultures were frequently moved to promote growth and carefully examined for purity. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was used to solubilize the samples. Petri dishes were filled with twenty milliliters of aseptic Mueller Hinton agar (Sigma, Paris, France) and then inoculated with a 200 µL cell solution. Using the McFarland 0.5 procedure, the concentration of the cell suspension was brought down to 106colony-forming units per milliliter (cfu/mL). Six-millimeter filter paper discs, free of bacteria or other microorganisms, were soaked in 20 µL of the extract solution. These discs were then deposited on the agar surface. The plates were kept in an incubator for twenty-four hours at 37 °C. Imipenem (10 µg) and fluconazole (0.6 µg) were used as positive controls by the experimental group. Paper discs containing 20 µL of pure water or DMSO served as the negative controls. Digital calipers were used to measure the inhibitory zones, and to reduce error, the measurements were made three times. A serial dilution method was used to find the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for microbial growth in 96-well microtiter plates43. The exact amount of extract used in the test was found by taking out the solvent from 1 mL of extract, soaking the dry extract in 20% v/v DMSO, and then diluting it by a factor of 10 in Mueller-Hinton broth. 100 µL of the bacterial or fungal solutions and dilutions were then put into microtiter plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Mueller-Hinton broth mixed with 100 µL of bacterial solution made up the positive control. On the other hand, 100 µL of diluent was combined with 100 µL of bacterial-free extract to create the negative control. After 24 h, the turbidity of the positive and negative results was evaluated relative to the control well. Given that a clear well was present, the MIC values were identified as the minimal concentration of the extract (from 16 to 1000 µg/mL) that completely inhibited microbial growth. Three different experiments were run to determine the validity of each extract.

Molecular docking study

The molecular docking analysis was performed using the Maestro 11.5 software from the Schrodinger suite, which is well-known for its ability to optimize lead compounds, perform virtual screening, and provide detailed insights into protein-ligand interactions. The study’s goal was to find out how the chemicals in two fig pastes interact with the active sites of four different target proteins. These proteins are NADPH oxidase, β-ketoacyl-[acyl carrier protein] synthase from Escherichia coli, nucleoside diphosphate kinase from Staphylococcus aureus, and sterol 14-α demethylase (CYP51) from the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. The aim was to evaluate the antioxidant and antibacterial characteristics of the fig pastes. The glide gscore, measured in Kcal/mol, represents the potential energy alteration that occurs when the protein and ligand interact. Consequently, a highly negative score indicates a robust binding, while a less negative or even positive value indicates a weak or nonexistent binding.

Protein preparation

We got the crystal structures of the target proteins from the RCSB database. These are NADPH oxidase (PDB ID: 2CDU), β-ketoacyl-[acyl carrier protein] synthase from Escherichia coli (PDB ID: 1FJ4), nucleoside diphosphate kinase from Staphylococcus aureus (PDB ID: 3Q8U), and sterol 14-α demethylase (CYP51) from Candida albicans(PDB ID: 5FSA). The protein preparation process was carried out using the Protein Preparation Wizard in Maestro 11.5. This involved performing preprocessing, refinement, and reduction processes. Hydrogen atoms were introduced, and hydroxyl groups, water molecules, and amino acids were rearranged to address structural problems such as atom overlap or absence. The proteins were then subjected to minor optimization to improve their architecture44,45.

Ligand preparation

For ligand preparation, the Ligprep tool in Maestro 11.5, which is part of the Schrödinger suite, was used. During this process, 2D structures were turned into 3D ones, hydrogen atoms were added, bond length and angle errors were fixed, and structures were made as small as possible using the OPLS3 force field. The ionization states were modified, and the chirality was maintained during the preparation process46,47.

Receptor grid generation

Receptor grids were created using Glide molecular docking, which used the coordinates of the original ligands to determine the active sites. To investigate possible interaction conformations, the ligands were strategically placed in the protein’s X-ray crystal structure. The method also involved determining sites, borders, rotatable groups, and excluded volumes48,49.

Performing molecular docking

The docking process was performed using the Standard Precision (SP) mode, following the preparation of ligands and proteins and the construction of grids. This model was chosen to evaluate the binding interactions between molecules. Also found were the internal energy, root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), desolation energy, hydrogen bonding, lipophilic interactions, and π-π stacking interactions. The binding energies were given in kcal/mol. This method guarantees a swift and precise examination of the interactions between a ligand and a protein, offering an in-depth understanding of the mechanisms involved in binding50,51.

Statistical analysis

The correlation coefficients 2 for spectrophotometric tests were calculated with the Microsoft Office Excel 2021 software. We used IBM SPSS Statistics V21.0 software to do descriptive statistics, a t-student test or an ANOVA one-way of the studied characteristics at a 5% level of significance, and a bivariate Pearson correlation analysis with a level of significance of P < 0.01.

Results and discussions

Physicochemical assessment of fig pastes

Fig paste’s moisture, dry matter, ash, and organic matter

A t-test (α = 5%) showed no significant difference in moisture and dry matter content between CH and GD pastes (Table 1). However, significant differences were observed in ash and organic matter content.

CH paste contained more moisture than their GD counterparts (25.81 ± 0.13% vs. 25.32 ± 0.45%); these proportions are in line with the standard of untreated dried figs that should not have moisture levels above 26.0%52. Understanding the moisture level of an agricultural product is crucial since it directly impacts the weight of the product but does not contribute to the nutritional value of the animal. While animals do need water, it is crucial to supply them with water directly rather than relying on water content in their food53. The main objective of drying is to extend the shelf life of the product by reducing the moisture content and water activity to inhibit microbial growth and enzymatic activity. However, the slowness of the process, depending on climatic conditions, can lead to various problems, such as the growth and proliferation of microorganisms and the loss of nutritional compounds54.

The dry matter content of the GD paste is higher than that of the CH paste (74.7 ± 0.45% vs. 74.20 ± 0.13%). The essential nutrients required for animal maintenance, growth, pregnancy, and lactation are contained in the dry matter of the feed53.

The ash content of CH fig paste was higher (2.90 ± 0.01%) compared to GD paste (2.39 ± 0.04%). Conversely, GD fig paste had a higher organic matter content of 97.61 ± 0.04%, while CH fig paste had a lower organic matter content of 97.10 ± 0.01%. The variations in ash and organic matter content between both varieties may be attributed to factors such as soil qualities, plant age, geographic origin, climatic circumstances, vegetative cycle, or genetic background55,56. Aljane et al. (2009) found that the differences in the ash results were most likely due to genetic traits rather than that of applied agro-technical measures and ecological growing conditions57.

Fig paste extracts pH, titratable acidity, total soluble solids (Brix), and conductivity

The t-test at 5% significance level (see Table 1) shows that the pH, titratable acidity, and conductivity of the CH and GD pastes are very different. On the other hand, the identical statistical analysis showed no discernible difference between them in terms of soluble solids content (Brix).

The GD paste has a pH of 4.62, which is slightly lower than the pH of 4.71 of the CH paste, indicating a more acidic nature. The reported acidic pH is due to the low water content of the samples, with organic acids being the most common. The pH is an important component in food quality management and a key criterion for the classification of fruit and vegetables as it affects their preservation. Studies have shown that a product with an acidic pH is more resistant to biological and enzymatic changes than one with a neutral pH30.

Titratable acidity quantifies the total amount of acids present in a sample, and it serves as a valuable indicator for estimating the optimal time for harvesting and assessing the fruit’s level of ripeness in terms of sugar content. Typically, the amount of organic acid in food decreases as it matures. The titratable acidity of GD paste was significantly higher than that of CH paste. Acidity influences taste; lower acidity may result in a bland flavor, while excessive acidity can lead to an overly sharp taste58,59.

The Brix content of CH paste was somewhat greater (19.25 ± 0.05) than that of GD (19.18 ± 0.16). Any solid that dissolves in water is referred to as a solubilized solid. This includes carboxylic acids, sugars, proteins, and salts30.

Conductivity measurements give an approximation of the total number of ions in a solution. CH paste had the highest electrical conductivity values (92.65 ± 0.81 mS.m−1), whereas GD had the lowest values (85.08 ± 1.08 mS.m−1). These results are similar to those reported in dried figs from the same varieties in Eastern Morocco (CH: 94.67–95.08 mS.m−1and GD: 81.29–82.2 mS.m−1)30, and in dried fig from Moroccan markets (75.6–95.4 mS.m−1)31.

Fig paste macronutrients and vitamin C content

Based on the t-test conducted at a 5% significance level (refer to Table 1), it is evident that there are significant differences in the total sugars, lipids, crude fiber, and vitamin C content between the CH and GD pastes. However, the same statistical analysis showed no noticeable difference between them regarding protein content.

The total sugar concentration is important for the taste and ripeness of the fruit. It also plays a role in its stability and shelf-life60. In this case, the sugar amount in CH paste is higher (52.45%) compared to GD paste (51.01%). These findings regarding total sugar content are consistent with the study outcomes reported by the Informatics Centre on Food Quality (CIQUAL) and the National Centre for Veterinary and Food Studies (CNEVA) for dried Fig. (48.6–61.6%), and are significantly higher than the results obtained for freshly harvested Fig. (9.5–16.5%)61.

The lipid content of CH paste is higher (1.51 ± 0.43%) compared to GD (1.10 ± 0.025%). The results for lipid content are aligned with those reported by CIQUAL and CNEVA for dried Fig. (0.0–1.7%), and are higher than the values observed for fresh Fig. (0.0–0.5%)61.Lipids are vital biological constituents that provide the requisite energy, fatty acids, and fat-soluble vitamins62. GD paste has a lower protein level (3.25 ± 0.18%) compared to CH paste (3.55 ± 0.08%). These findings on protein levels are in line with the results of the CIQUAL and CNEVA studies on dried Fig. (2.7–4.2%) and are higher than those obtained for fresh Fig. (0.8–1.3%)61. Despite their inferior biological value compared to animal proteins, plant proteins serve vital purposes in human diets, such as enzyme and transporter activities as well as allergen defense agents63.

The crude fiber content of CH paste is lower (5.43 ± 0.24%) than that of GD paste (5.67 ± 0.19%). The levels of crude fiber found in this study are relatively low compared to those reported by CIQUAL and CNEVA for dried Fig. (7.5–16.2%), but higher than those found for fresh Figs. (2–2.8%)61. Plant cell wall complex carbohydrates like cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin are examples of dietary fibers that are indigestible to humans. People who consume a diet high in fiber seem to have a greatly reduced chance of developing cardiovascular disease, stroke, high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, and a few gastrointestinal disorders64.

The GD paste has a vitamin C concentration of 1.01 mg/100 g, while the CH paste has a higher concentration of 1.14 mg/100 g. These results for vitamin C concentration are in line with the results of the CIQUAL and CNEVA studies for dried Figs. (0–5 mg/100 g) and fresh Figs. (1–15 mg/100 g)61. Because of its biological activities in the human body, vitamin C is critical for food quality in many horticulture crops65. Fruit variety, post-harvest handling circumstances, pre-harvest environmental variables (such as sun exposure, cultural practices, maturity, and harvesting method), and genotypic features are some of the many factors that influence the variation in vitamin C content in fruit65,66.

The values having different letters in lines are significantly different according to the t-test (P < 0.05) and (n = 3).

Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of fig paste

Upon examination of the t-test 5% findings for TPC, TFC, and TAC, as well as the ANOVA 5% of the IC50 DPPH radical scavenging test (Table 2), it became apparent that the hydroethanol extracts of CH and GD pastes were not identical.

Ghoudane hydroethanol extract (GDHEE) has the most abundant amount of polyphenols, with a concentration of 374.6 ± 4.57 mg GAE/100 g DW, whereas chetoui hydroethanol extract (CHHEE) has the least amount, with a concentration of 306.4 ± 1.80 mg GAE/100 g DW. The type and concentration of solvent, temperature, time, sample/solvent ratio, number of extractions, and the method used for quantitative measurement are some of the most important influences when evaluating the polyphenol content of a plant extract. The main disadvantage of the colorimetric assay is its limited specificity for the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, which works best with phenolic compounds but also works with carbohydrates and proteins, although to a lesser extent67. Polyphenols are the predominant bioactive compounds found in our diet, with an average intake of 1 g/day. This amount is approximately 10 times higher than the intake of vitamin C68. Secondary metabolites such as polyphenols are widely distributed in plant foods, present not just in fruits and vegetables but also in cereals, legumes, tea, coffee, and chocolate69.

The GDHEE contains more flavonoid content (102.5 ± 2.16 mg of QE/100 g) than CHHEE (81.52 ± 1.37 mg of QE/100 g). Flavonoids are now considered an essential component of many medical, pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and cosmetic goods. This is due to their ability to influence key cellular enzyme function, as well as their anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-mutagenic, and anti-carcinogenic properties70.

The antioxidant activity of the two fig pastes under investigation was assessed using two distinct methodologies (Table 2). Both antioxidant activity evaluations indicated that GDHEE had the highest antioxidant activity compared to the CHHEE.

According to the TAC method, GDHEE had the highest phosphomolybdenum reduction (80.16 ± 0.83 µg AAE/mg extract) compared to CHHEE, which had 73.37 ± 0.96 µg AAE/mg extract. The difference in TAC between the two fig pastes studied is statistically significant according to the t-student test at 5% threshold.

The DPPH IC50 value and the percentage inhibition are inversely related; a lower IC50 value indicates increased antioxidant potency. Based on the DPPH IC50 results in this experiment. The ANOVA shows a significant difference (P < 0.05) between the two hydroethanol paste extracts studied and between them and the standard ascorbic acid.

The values having different letters in lines are significantly different according to the t-test* or One-way ANOVA** Tukey test (P < 0.05) and (n = 3). CHHEE,. Chetoui hydroethanol extract; GDHEE,. Ghoudane hydroethanol extract.

Using DPPH equivalence to measure the antioxidant activity of the extracts in mg/mL, they ranked in this order: the stronger antioxidant is the standard vitamin C (1.5 ± 0.10), followed by GDHEE (5.62 ± 0.02) and finally CHHEE (6.82 ± 0.02).

A bivariate Pearson correlation analysis was performed (Table 3) to investigate the association between antioxidants and their effectiveness in eliminating free radicals. The results showed a significant and positive association (correlation coefficient = 0.978) between total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC). There were also identical, robust negative correlations between TPC or TFC and vitamin C, with correlation coefficients of −0.961. Nevertheless, the results show that it is the polyphenolic and flavonoid components in the hydro-ethanol extracts of the fig pastes studied that is mainly responsible for the antioxidant action to get rid of harmful free radicals. This is evidenced by their strong and negative association with DPPH IC50 (−0.997 for TPC and − 0.987 for TFC). There is also a strong positive association with TAC, with a correlation coefficient of 0.961 for TPC and 0.989 for TFC. On the other hand, there is a significant positive correlation between vitamin C and DPPH IC50 (0.976) and a significant negative correlation between vitamin C and TAC (−0.951). This means that the anti-free radical function of vitamin C is reduced.

Bivariate Pearson correlation analysis with a significance level of P < 0.01. DPPH., DPPH Scavenging assay IC50; TAC., Total Antioxidant Capacity; TPC., Total polyphenol content; TFC., Total flavonoid content; Vit C., Vitamin C.

Fig paste phytochemicals compounds

According to the HPLC-UV-MS/MS analysis (Table 4) of the hydroethanolic extracts of the two fig pastes studied, a variety of phytochemicals such as phenolic acids, flavonoids, and organic acids are present in both paste extracts, although with some compositional differences.

Gallic acid is the main compound detected in the paste extract of CH, whereas catechin is the main compound detected in the paste extract of GD. The two paste extracts have different amounts of ascorbic acid, quercetin 3’-methyl ether, caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, and salicylic acid. The main constituents present in both pastes are quercetin, 3’-methylether, and neochlorogenic acid. Naringin is present exclusively at the GDHEE level, while rutin hydrate and trans-cinnamic acid are present exclusively at the CHHEE level.

The antioxidant potential of F. caricafruits is strongly linked to their phenolic content71. Hyang Dok-Go et al. (2002) showed that quercetin 3-methyl ether effectively prevents neuronal damage caused by H2O2 and xanthine (X)/xanthine oxidase (XO). They found that quercetin 3-methyl ether (QME) was the most neuroprotective compared to the other flavonoids isolated, quercetin and (+)-dihydroquercetin. All three principles significantly inhibited lipid peroxidation and scavenged 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl free radicals72. Luisa Pistelli et al. (2009) found a narrow spectrum of activity against Staphylococcus epidermidis (gram-positive). The MIC values of the extracts ranged from 125 to 850 µg/mL. Quercetin 3-methylether, myricetin 3-O-rhamnoside, and tricetin showed antibacterial activity against the same bacterial strains with MICs ranging from 31 to 250 µg/mL. In time-kill kinetic studies, the flavonoids showed bactericidal activity at concentrations corresponding to four times the MICs73.

Chlorogenic acid and neochlorogenic acid have been shown in various studies to protect the kidneys, fight free radicals, and help with diabetes, cancer, cholinesterase, and inflammation74,75,76,77.

Agnieszka Tajner-Czopek et al. (2020) show that there is a strong correlation between 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid and the antioxidant activity based on the ABTS and the DPPH test results78. Several studies have shown that consumption of caffeoylquinic acids has health benefits such as antiviral, hepatoprotective, and hypoglycemic effects. This is particularly true in the case of the medicinal hydroethanolic plant extract79,80,81.

Ascorbic acid, a potent physiological antioxidant, can restore the body’s levels of α-tocopherol (vitamin E) and other antioxidants. Various oxidative stress-related illnesses, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer, are currently under investigation to determine if they might be prevented or delayed by ascorbic acid. It achieves this by reducing the harmful effects of free radicals through its antioxidant properties. Ascorbic acid has multiple roles, including antioxidant activity, biosynthesis, and enhancement of nonheme iron absorption66,82,83.

Caffeic acid, a phenolic chemical produced by plants, can be found in coffee, wine, tea, and propolis. This phenolic acid and its derivatives have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticarcinogenic properties80. It has been shown to have anticarcinogenic activity against hepatocarcinoma (HCC) in both in vitro and in vivo studies. It also plays a role in plant defense against pests and infections by inhibiting the growth of insects, fungi, and bacteria84.

Researchers found that rutin hydrate, the main phenolic in the fig peel sample, had great antioxidant properties both in vitro and in vivo antioxidant characteristics, among other bioactivities85.

Antimicrobial activity of fig pastes

The efficacy of the hydroethanol extracts obtained from both fig pastes against the investigated microorganisms exhibited diversity (Fig. 4). The results of the ANOVA analysis with Tukey’s post-hoc test, conducted at a significance threshold of 5%, indicated significant differences in antimicrobial effectiveness against the four bacteria and fungi studied between GDHEE and CHHEE, as well as the reference bactericidal drugs imipenem and the fungicidal fluconazole.

Disk diffusion assay results for the investigated paste extracts and reference drugs. E. coli. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922; P. aeruginosa., Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853; S. aureus., Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923; B. subtilis., Bacillus subtilis subsp. Spizizenii ATCC 6633; C. albicans., Candida albican (Clinical isolated); CHHEE,. Chetoui hydroethanol extract; GDHEE,. Ghoudane hydroethanol extract. Inhibition zones including the diameter of the paper disc (6 mm). Each value is represented as mean ± standard deviation, (n = 3). Means followed by a different letter in the same strain are significantly different (ANOVA One-way P < 0.05.

The antimicrobial activity is significantly higher when the inhibition zone, including the 6 mm of the disc diameter, has a diameter of 14 mm or more86. The reference drugs showed a stronger inhibitory effect. The enhanced antimicrobial efficacy of GDHEE, as opposed to CHHEE, can be ascribed to its higher concentration of bioactive components, such as polyphenols, flavonoids, and ascorbic acid. It is worth noting that the extracts from both pastes were highly efficient against Candida albicans, with the CHHEE showing the lowest impact (18.60 ± 0.2 mm) and the GDHEE exhibiting the highest effect (20.40 ± 0.1 mm). Concerning Gram-negative bacteria, GDHEE showed the highest inhibitory effect activity against Escherichia coli (12.60 ± 0.10 mm), followed by CHHEE (12.00 ± 0.20 mm). However, the highest inhibitory was observed by GDHEE (13.80 ± 1.0 mm) against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, while CHHEE demonstrated a smaller inhibition diameter (11.30 ± 0.80 mm). Regarding Gram-positive bacteria, GDHEE exhibited greater inhibitory activity (11.40 ± 0.10 mm) compared to CHHEE (10.00 ± 0.3 mm) against Staphylococcus aureus. Moreover, paste extract inhibited Bacillus subtilis subsp. spizizenii, with the GDHEE exhibiting the highest inhibitory effect (14.00 ± 0.30 mm), followed by the CHHEE (11.20 ± 0.4 mm).

A statistical analysis using the student’s t test, with a significance level of 5%, revealed that GDHEE and CHHEE had significantly different minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Bacillus subtilis subsp. spizizenii. However, there were no significant differences between GDHEE and CHHEE for Escherichia coli and Candida albicans.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC values) in µg/mL for the investigated pastes extracts. E. coli. Escherichia coli ATCC 25,922; P. aeruginosa., Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27,853; S. aureus., Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25,923; B. subtilis., Bacillus subtilis subsp. Spizizenii ATCC 6633; C. albicans., Candida albican (Clinical isolated); CHHEE,. Chetoui hydroethanol extract; GDHEE,. Ghoudane hydroethanol extract. Each MIC value is represented as mean ± standard deviation, (n = 3). Means followed by a different letter in the same strain are significantly different (t-test, P < 0.05).

The MIC value is determined by a complex interaction between the variety, the extraction solvent, the amount of active principle extracted, and the microbial strains that the extract is targeting30. Extracts were categorized as highly active when MICs were below 100 µg/mL, moderately active when values ranged from 100 to 625 µg/mL, and weakly active when values exceeded 625 µg/mL87. The examination of the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) values of the two pastes of extracts from CH and GD (depicted in Fig. 5) demonstrated that hydroethanolic extracts from both varieties displayed the same MIC of 64 µg/mL against Escherichia coli. However, the GDHEE showed a MIC of 32 µg/mL against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, while the CHHEE exhibited a MIC of 64 µg/mL. The GDHEE exhibited a MIC of 128 µg/mL against Staphylococcus aureus, whereas the CHHEE demonstrated a MIC of 256 µg/mL. Bacillus subtilis subsp. spizizenii exhibited higher sensitivity to GDHEE, with a MIC of 128 µg/mL. In contrast, it displayed lower sensitivity to CHHEE, with a MIC of 256 µg/mL. The GDHEE and CHHEE demonstrated a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 32 µg/mL against Candida albicans.

The concentration and content of bioactive compounds and minerals may have contributed to the extracts’ antimicrobial effectiveness against various strains. Certain minerals and bioactive chemicals, such as polyphenols, can interact to boost or decrease antimicrobial activity in plants and extracts, respectively88. Many recent studies have revealed that medicinal mineral compounds work as antimicrobials by interacting synergistically with bioactive components in plant extracts such as Phenolic acids, flavonoids, terpenoids, and others, or by changing pH89. Plants synthesize flavonoids and coumarins as a defensive reaction to microbial diseases. The capacity of these chemicals to engage with extracellular and soluble proteins, as well as bacterial cell walls, might contribute to their reported effectiveness. Moreover, lipophilic flavonoids possess the ability to harm microbial membranes and behave as bioactive compounds that can engage with microbes in many manners, thereby influencing their growth and survival90,91.

In silico antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of fig paste

In silico antioxidant activity assessment

NADPH oxidase (NOX) is an essential enzyme responsible for producing reactive oxygen species (ROS), and its activity is tightly controlled within cells. NADPH oxidase creates reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are very important for fighting infections and letting cells talk to each other. Several respiratory inflammatory diseases and injuries, like asthma, cystic fibrosis, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), are thought to be caused by oxidative stress, which happens when NADPH oxidase makes too many reactive oxygen species (ROS). Inhibiting the function of NADPH oxidase is a very efficient approach to boost antioxidant activity and offer defense against diseases linked to oxidative stress92. NADPH oxidase inhibitors can maintain cellular health and impede disease progression by decreasing reactive oxygen species (ROS), increasing cellular antioxidant systems, and alleviating chronic inflammation. According to our computational analysis (Table 5), quercetin 3-methyl ether, 3, 4-dicaffeoylquinic acid, and rutin hydrate showed the most significant action against NADPH oxidase, with glide gscore values of −6.307, −6.249, and − 5.979 Kcal/mol, respectively. Figure 6A and A’ show that quercetin 3-methyl ether has made two hydrogen bonds with VAL 214 (distance, 2.17 Å) and ASP 179 (distance, 1.66 Å) residues in the active site of NADPH oxidase.

In silico antibacterial activity assessement

The main role of β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase is to produce fatty acids of varying lengths for the organism’s use. These applications involve energy storage and cell membrane creation. Fatty acids possess the capacity to produce a wide range of compounds, including prostaglandins, phospholipids, and vitamins, among other substances93. β-ketoacyl-ACP synthases play a crucial role in the biosynthesis of lipoproteins, phospholipids, and lipopolysaccharides. Because of their numerous vital functions within the body, they have become a central area of concentration for the advancement of antibacterial medications. Bacteria adapt to their environment by altering the composition of their membranes through phospholipid modifications. Hence, obstructing this pathway could function as a critical site for hindering the spread of microorganisms94. Out of the compounds tested for antibacterial effect, neochlorogenic acid, salicylic acid, and gallic acid showed the greatest level of activity against β-ketoacyl-[acyl carrier protein] synthase from Escherichia coli, with glide gscores of −7.357, −6.872, and − 6.755 Kcal/mol, respectively (Table 5). neochlorogenic acid formed three hydrogen bonds with VAL 304 (distance, 1.91 Å), THR 302 (distance, 1.76 Å), and ASN 396 (distance, 2.77 Å) parts in the active site of Escherichia coli β- ketoacyl [acyl carrier protein] synthase (Fig. 7A and A’).

Bacterial diphosphate kinase (Ndk) regulates the cellular levels of nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) by transferring the γ-phosphate group between NTPs and nucleoside diphosphate (NDPs). Aside from its main role in nucleotide metabolism, Ndk also plays a part in protein histidine phosphorylation, DNA cleavage and repair, and gene regulation. Ndk also regulates bacterial adaptive responses. Intracellularly produced non-self-derived molecules, known as ndks, effectively inhibit multiple immune defense mechanisms in the host. These processes encompass phagocytosis, cell apoptosis/necrosis, ROS production, and inflammation. On the other hand, Ndks released by bacteria outside of cells worsens host cell toxicity and inflammatory response. While Ndks from both intra- and extracellular bacteria have diverse effects on host cellular events, their fundamental purpose remains consistent: to create a host environment that is favorable for colonization and spread95. As a result, suppressing Ndk is a successful approach to preventing bacterial development. Furthermore, neochlorogenic acid, gallic acid, and salicylic acid exhibited the most potent effects against Staphylococcus aureus nucleoside diphosphate kinase, as indicated by their glide gscore values of −10.493, −10.050, and − 9.601 kcal/mol, respectively (Table 5). Also, neochlorogenic acid made a single hydrogen bond with residue ASP B: 60 (distance, 2.44 Å) in the active site of Staphylococcus aureus nucleoside diphosphate kinase (see Fig. 8A and A’).

In silico antifungal activity assessment

Lanosterol, or sterol 14α-demethylase, is an enzyme classified as a member of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily. It is associated with the CYP51 family, which is a vital enzyme involved in the formation of sterols in eukaryotes. This enzyme is a key target for anti-fungal azoles and has the potential for antiprotozoan chemotherapy. Although 14α-demethylase is present in other organisms, it is primarily studied in fungi because of its vital role in controlling membrane permeability96. The enzyme CYP51 in fungi is responsible for the degradation of lanosterol, a crucial precursor that is subsequently converted into ergosterol97. This steroid subsequently diffuses throughout the cell, altering the permeability and rigidity of the plasma membrane in a way comparable to cholesterol in animals98. Because ergosterol plays a vital role in fungal membranes, many antifungal medicines have been developed to inhibit the function of 14α-demethylase, thereby disrupting the production of this important molecule98. Another thing is that catechin, chlorogenic acid, and quercetin 3-methyl ether were the most effective antifungal compounds against CYP51 from the harmful fungus Candida albicans. Their respective glide gscores were − 7.638, −7.097, and − 7.07 kcal/mol (Table 5). Also, catechin formed one hydrogen bond and one Pi-Pi stacking with CYP51 from the active site of the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans (Fig. 9A and A’). These bonds were with residues MET 508 (distance, 1.77 Å) and PHE 233 respectively.

Glide gscore mesure the interaction between the boactive compound and the protein targeted in (Kcal/mol).

Conclusion

The nutritional, phytochemical, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of GD and CH fig paste were evaluated to determine their functional dietary potential and health benefits. The photochemistry HPLC-UV-MS/MS analysis of fig paste reveals the presence of bioactive compounds, lending credence to their usage in traditional medicine for a range of ailments. The health advantages of fig extracts have been demonstrated in in vitro and in silico bioactivity investigations. This will greatly benefit the fields of pharmacology and nutraceuticals. The research results show that fig paste contains antimicrobial, antioxidant, and polyphenolic substances such as flavonoids. These findings support the idea that the paste method can be utilized to protect the antioxidants and bioactive chemicals contained in fig fruit. These pastes should be encouraged because they contain antioxidants and can be a healthy substitute for harmful food options. Factors such as fruit variety, food matrix, pH, enzyme presence, and others had an impact on the paste samples’ bioactive composition and antioxidant capacity. It would be highly beneficial to study the bioavailability of bioactive components in fig pastes in comparison to other valorisation techniques such as dried fig, fig coffee, fig jam, and fig vinegar. Fig paste is a versatile food product that satisfies customer demands for a wide range of beneficial components, including physiologically active antioxidants and antimicrobials. Individuals can utilize these kinds of fig fruit in both health and manufacturing products. Fig paste is ideal for desserts, pastries, pancakes, and hot beverages. Traditionally, fig paste is used in fig cookies, energy and health food bars, as well as spreads, sauces, jams, and fruit fillings.

Fig pastes are characterized by ingredients and functional properties that make them suitable for use in the food industry as they provide many health benefits. To maximize the value of these pastes, their use should be carefully considered. However, further research, including in vivo tests, is needed to validate these biological activities. In addition, pharmacological research should be carried out to confirm or optimize efficacy and to investigate side effects. Ficus carica is a plant with a variety of medicinal properties and potential therapeutic applications. In addition, its utilization can provide benefits by ensuring the sustainable management of this resource. Further research on the incorporation of this paste or its extracts into food matrices is recommended to achieve potential benefits.

Data availability

All the data relevant to this study has been added to the manuscript.

References

Storey, W. & Fig. (1975).

Tırkaz, E., Balcı, B. & Aksoy, U. in Advances in Fig Research and Sustainable Production 472–494CABI GB, (2022).

Macheix, J. J., Fleuriet, A. & Jay-Allemand, C. Les composés phénoliques des végétaux: un exemple de métabolites secondaires d’importance économique (PPUR presses polytechniques, 2005).

Stover, E., Aradhya, M., Crisosto, C. & Ferguson, L. in Proceedings of the California Plant and Soil Conference.

Gani, G., Fatima, T., Qadri, T., Beenish Jan, N. & Bashir, O. Phytochemistry and Pharmacological activities of Fig (Ficuscarica): A review. Inter J. Res. Pharm. Pharmaceut Sci. 3, 80–82 (2018).

Mutha, R. E., Tatiya, A. U. & Surana, S. J. Flavonoids as natural phenolic compounds and their role in therapeutics: an overview. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 7, 1–13 (2021).

Alara, O. R., Abdurahman, N. H. & Ukaegbu, C. I. Extraction of phenolic compounds: A review. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 4, 200–214 (2021).

Oliveira, A. P. et al. Ficus carica L.: metabolic and biological screening. Food Chem. Toxicol. 47, 2841–2846 (2009).

Vallejo, F., Marín, J. & Tomás-Barberán, F. A. Phenolic compound content of fresh and dried figs (Ficus carica L). Food Chem. 130, 485–492 (2012).

Veberic, R., Colaric, M. & Stampar, F. Phenolic acids and flavonoids of Fig fruit (Ficus carica L.) in the Northern mediterranean region. Food Chem. 106, 153–157 (2008).

Kaur, C. & Kapoor, H. C. Anti-oxidant activity and total phenolic content of some Asian vegetables. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 37, 153–161 (2002).

Naoui, H. et al. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of lipids from Ficus carica L. fruits. Chem. J. Moldova. 18, 92–101 (2023).

Badgujar, S. B., Patel, V. V., Bandivdekar, A. H. & Mahajan, R. T. Traditional uses, phytochemistry and Pharmacology of Ficus carica: A review. Pharm. Biol. 52, 1487–1503 (2014).

Nakilcioğlu-Taş, E. Biochemical characterization of Fig (Ficus carica L.) seeds. J. Agricultural Sci. 25, 232–237 (2019).

Rajendran, E. G. M. G. In Fig (Ficus carica): Production, Processing, and Properties357–368 (Springer, 2023).

Erdoğan, Ü. & Gökçe, E. H. Fig seed oil-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers: evaluation of the protective effects against oxidation. J. Food Process. Preserv. 45, e15835 (2021).

Baygeldi, N., Küçükerdönmez, Ö., Akder, R. N. & Çağındı, Ö. Medicinal and nutritional analysis of Fig (Ficus carica) seed oil; a new gamma Tocopherol and omega-3 source. Progress Nutr. 23, 1–6 (2021).

Kumar, K. & Singh, D. In Dryland Horticulture533–546 (CRC, 2021).

Taviano, M. F. et al. Juniperus oxycedrus L. Subsp. oxycedrus and Juniperus oxycedrus L. Subsp. Macrocarpa (Sibth. & Sm.) ball.berries from Turkey: comparative evaluation of phenolic profile, antioxidant, cytotoxic and antimicrobial activities. Food Chem. Toxicol. 58, 22–29 (2013).

Yuan, H., Ma, Q., Ye, L. & Piao, G. The traditional medicine and modern medicine from natural products. Molecules 21, 559 (2016).

Garnero, J. Les huiles essentielles, leurs obtentions, leurs compositions, leurs analyses et leurs normalisations. Ed. Techniques, Encycl. Med-Nat.(Paris, France) (1991).

Guinoiseau, E. Molécules antibactériennes issues d’huiles essentielles: séparation, identification et mode d’action (Université de Corse, 2010).

Tikent, A. et al. in E3S Web of Conferences. 04008 (EDP Sciences).

IPGRI, C. Descriptors for fig. International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy, and International Centre for Advanced Mediterranean Agronomic Studies, Paris, France 52 (2003).

Tikent, A. et al. Antioxidant potential, antimicrobial activity, polyphenol profile analysis, and cytotoxicity against breast cancer cell lines of hydroethanolic extracts of leaves of (Ficus carica L.) from Eastern Morocco. Front. Chem, 2024. 12, 1505473.

Bucic-Kojic, A. et al. Effect of extraction conditions on the extractability of phenolic compounds from lyophilised Fig fruits (Ficus carica L). Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 61(3), 195–199 (2011).

Nielsen, S. S. Determination of moisture content. Food Anal. Lab. Man., 17–27 (2010).

Harris, G. K. in Nielsen’s Food Analysis 261–271Springer, (2024).

Belguedj, M. (Dossier, (2002).

Tikent, A. et al. The antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of two Sun-Dried Fig varieties (Ficus carica L.) produced in Eastern Morocco and the investigation of Pomological, colorimetric, and phytochemical characteristics for improved valorization. Int. J. Plant. Biology. 14, 845–863 (2023).

Al Askari, G., Kahouadji, A., Khedid, K., Charof, R. & Mennane, Z. Caractérisations physico-chimique et microbiologique de La Figue Sèche prélevée des marchés de Rabat-Salé, Temara et Casablanca. Les Technol. De Laboratoire, 7(26), (2012).

DuBois, M., Gilles, K. A., Hamilton, J. K., Rebers, P. & Smith, F. t. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Analytical chemistry 28, 350–356 (1956).

Lepper, W. Estimation of crude fibre by the Weende method. Landwirtschaftliche Versuchsstation. 117, 125–129 (1933).

Gourchala, F., Ouazouaz, M., Mihoub, F. & Henchiri, C. Compositional analysis and sensory profile of five date varieties grown in South Algeria. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 7, 511–518 (2015).

Kjeldahl, J. Neue methode Zur bestimmung des stickstoffs in organischen Körpern. Z. Für Analytische Chemie. 22, 366–382 (1883).

Velioglu, Y., Mazza, G., Gao, L. & Oomah, B. Antioxidant activity and total phenolics in selected fruits, vegetables, and grain products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 46, 4113–4117 (1998).

Dehpour, A. A., Ebrahimzadeh, M. A., Fazel, N. S. & Mohammad, N. S. Antioxidant activity of the methanol extract of Ferula assafoetida and its essential oil composition. Grasas Y Aceites. 60, 405–412 (2009).

Bouaouda, K. et al. HPLC-UV-MS/MS profiling of phenolics from Euphorbia nicaeensis (All.) leaf and stem and its antioxidant and anti-protein denaturation activities. Progress Microbes Mol. Biology 6(1), 20 (2023).

Chaudhary, S. et al. Evaluation of antioxidant and anticancer activity of extract and fractions of nardostachys Jatamansi DC in breast carcinoma. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 15 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-015-0563-1 (2015).

Taibi, M. et al. Evaluation of antioxidant activity, cytotoxicity, and genotoxicity of Ptychotis verticillata essential oil: towards novel breast Cancer therapeutics. Life 13, 1586 (2023).

Ouahabi, S. et al. Pharmacological properties of chemically characterized extracts from mastic tree: in vitro and in Silico assays. Life 13, 1393 (2023).

Prieto, P., Pineda, M. & Aguilar, M. Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of a phosphomolybdenum complex: specific application to the determination of vitamin E. Anal. Biochem. 269, 337–341 (1999).

Elof, J. A sensitive quick microplate method effect of Usnic acid O N mitotic index in root tips of to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration O F Allium cepa L. Lagascalia. Lagascalia 21, 47–52 (1998).

Tourabi, M. et al. Antioxidant, antimicrobial, and insecticidal properties of chemically characterized essential oils extracted from Mentha longifolia: in vitro and in Silico analysis. Plants 12, 3783 (2023).

Chebaibi, M. et al. Antiviral activities of compounds derived from medicinal plants against SARS-CoV-2 based on molecular Docking of proteases. J. Biology Biomedical Res. 1, 10–30. https://doi.org/10.69998/j2br1 (2024).

El Abdali, Y. et al. Essential oils of Origanum compactum Benth: chemical characterization, in vitro, in Silico, antioxidant, and antibacterial activities. Open. Chem. 21, 20220282 (2023).

Chebaibi, M. et al. Salsoline derivatives, Genistein, semisynthetic derivative of Kojic acid, and naringenin as inhibitors of A42R profilin-like protein of Monkeypox virus: in Silico studies. Front. Chem. 12, 1445606 (2024).

Ouahabi, S. et al. Study of the phytochemical composition, antioxidant properties, and in vitro anti-diabetic efficacy of Gracilaria bursa-pastoris extracts. Mar. Drugs. 21, 372 (2023).

Meryem, M. J., Agour, A., Allali, A., Chebaibi, M. & Bouia, A. Chemical composition, free radicals, pathogenic microbes, α-amylase and α-glucosidase suppressant proprieties of essential oil derived from Moroccan Mentha pulegium: in Silico and in vitro approaches. J. Biology Biomedical Res. 1, 46–61 (2024).

Amrati, F. E. Z. et al. Phenolic composition, wound healing, antinociceptive, and anticancer effects of Caralluma Europaea extracts. Molecules 28, 1780 (2023).

Mssillou, I., Agour, A., Lefrioui, Y. & Chebaibi, M. LC-TOFMS analysis, in vitro and in Silico antioxidant activity on NADPH oxidase, and toxicity assessment of an extract mixture based on Marrubium vulgare L. and Dittrichia viscosa L. J. Biology Biomedical Res. 1, 31–45. https://doi.org/10.69998/j2br2 (2024).

Unies., N. UNECE STANDARD DDP-15 concerning the marketing and control commercial quality of dried Figs. Nations Unies, New York and Genève. (2014). (2014) EDITION.

Massonneau, A. L’alimentation du furet: réalisation d’un guide pratique à destination des propriétaires, (2017).

Villalobos, M. et al. Evaluation of different drying systems as an alternative to sun drying for figs (Ficus carica L). Innovative Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 36, 156–165 (2016).

Athamena, S. Etude quantitative des flavonoïdes des graines de Cuminum cyminum et les feuilles de Rosmarinus officinalis et l’évaluation de l’activité biologique. Université De Batna, 2, 128, (2009).

Bezzala, A. Essai d’introduction de l’arganier (Argania spinosa (L.) Skeels) dans la zone de M’doukel et évaluation de quelques paramètres de résistance à la sécheresse. Mémoire. Magistère en Sciences Agronomiques. Option: Forêt et conservation des sols. Université El Hadj Lakhdar Faculté des Sciences-Batna. Algérie. 143p (2005).

Aljane, F. & Ferchichi, A. Postharvest chemical properties and mineral contents of some Fig (Ficus carica L.) cultivars in Tunisia. J. Food Agric. Environ. 7, e212 (2009).

Chahidi, B. et al. Utilisation de caractères morphologiques, physiologiques et de marqueurs moléculaires pour l’évaluation de La diversité génétique de Trois cultivars de Clémentinier. C.R. Biol. 331, 1–12 (2008).

Ferhoum, F. Analyses physico chimiques de la propolis locale selon les étages bioclimatiques et les deux races d’abeille locales (Apis mellifica intermissa et Apis mellifica sahariensis), Boumerdés, Université M’hamed Bougara (Faculté des Sciences de L’ingénieur, 2010).

Jiang, L. et al. Noninvasive evaluation of fructose, glucose, and sucrose contents in fig fruits during development using chlorophyll fluorescence and chemometrics. J. Agricultural Sci. Technol. 15, 333–342 (2013).

aliments, C. i. s. l. q. d. & Favier, J.-C. Répertoire général des aliments: Table de composition des fruits exotiques, fruits de cueillette d’Afrique. (Orstom Éditions, (1993).

GAOUAR, N. Etude de la valeur nutritive de la caroube de différentes variétés Algériennes. (2011).

Lacroix, M. Variations qualitatives & quantitatives de l’apport en protéines laitières chez l’animal & l’homme: implications métaboliques, Paris, AgroParisTech, (2008).

Ötles, S. & Ozgoz, S. Health effects of dietary fiber. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Technologia Aliment. 13, 191–202 (2014).

Lee, S. K. & Kader, A. A. Preharvest and postharvest factors influencing vitamin C content of horticultural crops. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 20, 207–220 (2000).

Gershoff, S. N. Vitamin C (ascorbic acid): new roles, new requirements? Nutr. Rev. 51, 313–326 (1993).

Falleh, H. et al. Phenolic composition of Cynara cardunculus L. organs, and their biological activities. C.R. Biol. 331, 372–379 (2008).

Faller, A. & Fialho, E. Polyphenol content and antioxidant capacity in organic and conventional plant foods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 23, 561–568 (2010).

Erdman, J. W. Jr et al. Flavonoids and heart health: proceedings of the ILSI North America flavonoids workshop, May 31–June 1, 2005, Washington, DC1. J. Nutr. 137, 718S–737S (2007).

Pande, G. & Akoh, C. C. Organic acids, antioxidant capacity, phenolic content and lipid characterisation of Georgia-grown underutilized fruit crops. Food Chem. 120, 1067–1075 (2010).

Arvaniti, O. S., Samaras, Y., Gatidou, G., Thomaidis, N. S. & Stasinakis, A. S. Review on fresh and dried figs: chemical analysis and occurrence of phytochemical compounds, antioxidant capacity and health effects. Food Res. Int. 119, 244–267 (2019).

Dok-Go, H. et al. Neuroprotective effects of antioxidative flavonoids, Quercetin,(+)-dihydroquercetin and Quercetin 3-methyl ether, isolated from Opuntia ficus-indica Var. Saboten. Brain Res. 965, 130–136 (2003).

Pistelli, L. et al. Antimicrobial activity of Inga fendleriana extracts and isolated flavonoids. Nat. Prod. Commun. 4, 1934578X0900401214 (2009).

Mawa, S., Husain, K. & Jantan, I. Ficus carica L.(Moraceae): phytochemistry, traditional uses and biological activities. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine (2013). (2013).

Takahashi, T., Okiura, A., Saito, K. & Kohno, M. Identification of phenylpropanoids in Fig (Ficus carica L.) leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62, 10076–10083 (2014).

Belguith-Hadriche, O. et al. HPLC-DAD-QTOF-MS profiling of phenolics from leaf extracts of two Tunisian Fig cultivars: potential as a functional food. Biomed. Pharmacother. 89, 185–193 (2017).

Ammar, S., del Mar Contreras, M., Belguith-Hadrich, O., Segura-Carretero, A. & Bouaziz, M. Assessment of the distribution of phenolic compounds and contribution to the antioxidant activity in Tunisian Fig leaves, fruits, skins and pulps using mass spectrometry-based analysis. Food Funct. 6, 3663–3677 (2015).

Tajner-Czopek, A. et al. Study of antioxidant activity of some medicinal plants having high content of caffeic acid derivatives. Antioxidants 9, 412 (2020).

Csepregi, R. et al. Cytotoxic, antimicrobial, antioxidant properties and effects on cell migration of phenolic compounds of selected Transylvanian medicinal plants. Antioxidants 9, 166 (2020).

Espíndola, K. M. M. et al. Chemical and Pharmacological aspects of caffeic acid and its activity in hepatocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 9, 541 (2019).

Marques, V. & Farah, A. Chlorogenic acids and related compounds in medicinal plants and infusions. Food Chem. 113, 1370–1376 (2009).

Frei, B., England, L. & N Ames, B. Ascorbate is an outstanding antioxidant in human blood plasma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 86, 6377–6381 (1989).

Jacob, R. A. & Sotoudeh, G. Vitamin C function and status in chronic disease. Nutr. Clin. Care. 5, 66–74 (2002).

Tošović, J. Spectroscopic features of caffeic acid: theoretical study. Kragujevac J. Sci., 99–108 (2017).

Gullon, B. et al. A review on extraction, identification and purification methods, biological activities and approaches to enhance its bioavailability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 67, 220–235 (2017).

Philip, K. et al. Antimicrobial activity of some medicinal plants from Malaysia. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 6, 1613 (2009).

Chusri, S., Sinvaraphan, N., Chaipak, P., Luxsananuwong, A. & Voravuthikunchai, S. P. Evaluation of antibacterial activity, phytochemical constituents, and cytotoxicity effects of Thai household ancient remedies. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 20, 909–918 (2014).

Cunningham, T. M., Koehl, J. L., Summers, J. S. & Haydel, S. E. pH-dependent metal ion toxicity influences the antibacterial activity of two natural mineral mixtures. PLoS One. 5, e9456 (2010).

Divakar, D. D. et al. Enhanced antimicrobial activity of naturally derived bioactive molecule Chitosan conjugated silver nanoparticle against dental implant pathogens. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 108, 790–797 (2018).

Tsuchiya, H. et al. Comparative study on the antibacterial activity of phytochemical flavanones against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 50, 27–34 (1996).

Al-Younis, N. & Abdullah, A. Isolation and antibacterial evaluation of plant extracts from some medicinal plants in Kurdistan region. J. Duhok Univ. 12, 250–255 (2009).

Lee, I. T. & Yang, C. M. Role of NADPH oxidase/ros in pro-inflammatory mediators-induced airway and pulmonary diseases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 84, 581–590 (2012).

Witkowski, A., Joshi, A. K. & Smith, S. Mechanism of the β-ketoacyl synthase reaction catalyzed by the animal fatty acid synthase. Biochemistry 41, 10877–10887 (2002).

Zhang, Y. M. & Rock, C. O. Membrane lipid homeostasis in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 222–233 (2008).

Yu, H., Rao, X. & Zhang, K. Nucleoside diphosphate kinase (Ndk): a pleiotropic effector manipulating bacterial virulence and adaptive responses. Microbiol. Res. 205, 125–134 (2017).

Daum, G., Lees, N. D., Bard, M. & Dickson, R. Biochemistry, cell biology and molecular biology of lipids of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14, 1471–1510 (1998).

Lepesheva, G. I. & Waterman, M. R. Sterol 14α-demethylase cytochrome P450 (CYP51), a P450 in all biological kingdoms. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-General Subj. 1770, 467–477 (2007).

Becher, R. & Wirsel, S. G. Fungal cytochrome P450 sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) and Azole resistance in plant and human pathogens. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 95, 825–840 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2025R119), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for funding this work. The invaluable assistance and unwavering support provided by the Laboratory of Agricultural Production Improvement, Biotechnology, and Environment (LAPABE), and in particular the Agri-food, Plant Ecophysiology and Biotechnology team at the Faculty of Science, Mohamed First University, are deeply appreciated. The authors wish to convey their appreciation to the complete staff of the Agri-Food Technologies and Quality Laboratory situated at the “Qualipôle alimentation de Béni-Mellal,” affiliated with the National Institute of Agricultural Research (INRA).

Funding

Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2025R119), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions