Abstract

This study aims to develop a composite hydrogel consisting of nano silver (Ag) and graphene oxide (GO) for use as a skin wound dressing. We prepared nanosilver/graphene oxide composite hydrogels by incorporating nanosilver and graphene oxide into kaolin-reinforced, gelatin-based hydrogels. Tests were conducted on the hydrogel’s water vapor permeability, mechanical properties, infrared warming performance and bacteriostatic properties under infrared light. The results indicated that kaolin enhanced the water vapor permeability and mechanical properties of the gelatin-based hydrogels. Moreover, the maximum fracture stress and strain of the hydrogel were elevated to 51.16 kPa and 1152.78% by GO, respectively. Furthermore, the modified Ag/GO hydrogels exhibited superior photothermal conversion and infrared bacteriostatic properties. This research offers valuable insights for the clinical repair of wounds and the design of new skin wound dressings, making these materials promising for such applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The skin, the largest organ of the human body, plays a critical role in regulating temperature and water balance, sensing external stimuli, protecting internal tissues and organs from damage, and resisting microbial invasion1,2. However, skin can be damaged by burns, impacts and other accidents. Due to the body’s limited capacity for self-repair, skin dressings are essential for promoting wound healing and preventing infection3. An ideal wound dressing should be non-toxic, non-irritating, non-allergenic and possess good swelling properties, air permeability, mechanical strength and excellent antibacterial properties4,5,6. Traditional dressings, such as gauze and bandages, are simple, cost-effective and widely used, but they are limited in function and can damage wounds during changes7. Thus, there is a need to develop new wound dressings.

Hydrogel, a hydrophilic material that is water-soluble, forms a three-dimensional network structure via various crosslinking methods, offering excellent swelling properties and biocompatibility8. Gelatin, a product derived from the hydrolysis of collagen from animal bones, skins and connective tissues, forms the basis of our hydrogels9. Gelatin-based hydrogels demonstrate good mechanical properties and biocompatibility, making them highly suitable for biomedical applications10,11. For example, a self-healing hydrogel was created by combining gelatin with tannic acid, which exhibited remarkable tensile deformation and rapid self-healing capabilities12. Through radiation induction, a composite of silver nitrate, chitosan and gelatin was crosslinked to form a hydrogel with proven antibacterial properties13. Additionally, a hydrogel composed of polyvinyl alcohol, glycerol and gelatin was created through hydrogen bonding self-assembly to mimic the dermis, maintaining excellent toughness and conductivity even at low temperatures and under frost conditions14.

Kaolin, a layered silicate clay mineral, is known for its outstanding surface activity and is commonly used as a nano-filler to interact and cross-link with polymers. When integrated into the gel matrix as inorganic particles, kaolin significantly enhances the mechanical strength of the matrix. Composite dressings involving the crosslinking of kaolin and calcium alginate (CaAlg) film have been developed, exhibiting ultra-high stiffness and enhanced pharmacokinetics15. Kaolin/CaAlg hydrogel composite membranes were prepared by incorporating kaolin into the CaAlg hydrogel matrix, which improved the mechanical properties of the CaAlg membranes16. In another study, kaolin/CaAlg free-standing membranes were produced by adding varying amounts of kaolin to a sodium alginate (NaAlg) casting solution and crosslinking with Ca2+ using urea as a porogen agent, significantly enhancing the mechanical behavior and flux of the resulting membranes17.

GO is a nanomaterial characterized by an extensive specific surface area, high mechanical strength, robust near-infrared light absorption and efficient heat conduction18,19. Additionally, GO’s surface is covered with many hydrophilic groups that can interact with other polymer segments. Compared to graphene, GO disperses more effectively in solutions without aggregating, which is advantageous for combining with hydrogels to enhance their photothermal and mechanical properties20. A degradable nano-composite hydrogel was prepared by incorporating lamellar graphene oxide into a quaternary ammonium salt matrix. This addition improved the biodegradability, flexibility and mechanical strength of the hydrogel, and it demonstrated a strong photothermal absorption effect and antibacterial performance21. Following the introduction of GO into the Fmoc-Pheself-assembling peptide hydrogels, there was a significant improvement in the viscoelastic properties and stiffness of the samples, making the hydrogels more stable and resilient22. Conductive hydrogels were developed by cross-linking gelatin methacryloyl with GO, maintaining mechanical properties at 1.89 ± 0.1 kPa and reaching up to 26.38 ± 2.29 kPa after mineralization23. By employing repeated freezing and thawing processes, GO was integrated into PVA hydrogel, which increased its tensile strength and compressive strength by 131% and 35% respectively, significantly enhancing the mechanical strength without compromising the biocompatibility of PVA24.

Due to its broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, nano-silver has been extensively utilized in producing skin wound dressings25. Nano-silver and GO were composited to create an effective antimicrobial system through a synergistic effect and introduced into the hydrogel system to enhance the antimicrobial properties of the hydrogel26,27. A novel hydrogel composed of polydopamine, Ag and GO was prepared by chemically cross-linking N-isopropylacrylamide and N,N′-methylene bisacrylamide for use as a wound dressing. Compared with conventional wound dressings, it exhibits excellent antimicrobial properties, high adhesion and strong contraction28.

Compared with traditional dressings, hydrogel wound dressings maintain the wound in an ideal moist environment, continuously absorb tissue fluid, and offer improved properties through structural design and functional integration. Currently, nanomaterials are often incorporated into hydrogel systems to enhance the overall capabilities of the hydrogels. As mentioned earlier, two nanomaterials, GO and nano-silver, have been studied and applied in hydrogels, and several research groups have conducted related studies. However, there are few examples of incorporating the Ag/GO complex into gelatin-based hydrogel. In this study, Ag/GO composite hydrogels were prepared by adding nanosilver and graphene oxide to kaolin-reinforced gelatin-based hydrogels. Among all the raw materials, in addition to gelatin as the base material of the hydrogel, sodium polyacrylate, glycerol and propylene glycol exhibit synergistic water absorption; sodium polyacrylate and polyethylene glycol show synergistic thickening; while kaolin plays a role in enhancing the mechanical properties of the hydrogel; and Ag and GO enable the hydrogel to exhibit significant synergistic photothermal effect and infrared antibacterial properties. The hydrogels were tested for water vapor permeability, mechanical properties, infrared warming performance and infrared bacterial inhibition performance. The purpose of this study is to prepare a skin dressing with excellent antibacterial and mechanical properties and to provide a new approach for clinical treatment and promoting skin wound healing.

Materials and methods

Materials

Glycerol and 1,2-Propylene Glycol were purchased from Tianjin Windship Chemical Reagent Technology Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Sodium Polyacrylate, Nano-Silver Powder (99.5%, 60–120 nm) and Kaolin were obtained from Shanghai McLean Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Polyethylene Glycol was sourced from Chengdu Kelong Chemical Reagent Factory (Chengdu, China). Gelatin was acquired from Yuan Ye Biologicals (Shanghai, China). GO was procured from Qitaihe Tailong Graphene Material Co., Ltd. (Heilongjiang, China). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was purchased from BMD Bioengineering Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Agar powder, Beef paste and Tryptone were supplied by Beijing Auberostar Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

Preparation of gelatin/sodium polyacrylate/kaolin hydrogel

Initially, gelatin was added to deionized water to prepare a 4% gelatin solution, and the mixture was stirred continuously for 4 h at 60 °C. Subsequently, 1 g of sodium polyacrylate, 1.8 mL of glycerol and 3 mL of propylene glycol were combined and ground using a mortar. Then, 0, 0.2, 0.4 and 0.6 g of kaolin were added respectively, and the mixture was stirred until the milky white particles completely dissolved, forming four groups. Next, 3 mL of the 4% gelatin solution was added to the previous mixture and stirred, followed by the addition of 1 mL of polyethylene glycol, which was then stirred continuously for 20 min. Finally, the solution was evenly spread onto a plate with a diameter of 15 cm and a thickness of 0.2 cm, and left to dry at room temperature. This process resulted in the formation of four groups of hydrogels: gelatin/kaolin 0, gelatin/kaolin 0.2, gelatin/kaolin 0.4 and gelatin/kaolin 0.6.

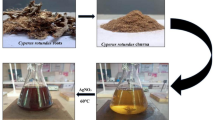

Preparation of nanosilver/graphene oxide hydrogels

The nanosilver/graphene oxide hydrogels were prepared according to the procedure illustrated in Fig. 1. Initially, lamellar graphene oxide (GO, 0.2 g) was ground into a fine powder in a mortar to prepare a graphene aqueous solution at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. This solution was sonicated for 40 min in an ultrasonic apparatus at 900 W and room temperature. Similarly, silver nanopowder (Ag, 0.2 g) was dissolved in water to achieve a silver nanopowder solution at a concentration of 1 mg/mL and sonicated under the same conditions. Finally, the gelatin/sodium polyacrylate/kaolin-0.4 mixture, GO solution and Ag solution were combined to form four groups: gelatin group, gelatin/Ag (0.3 mL Ag), gelatin/GO (0.3 mL GO) and gelatin/Ag/GO (Ag:GO, 0.3 mL:0.3 mL, v/v) (In the early stage of this study, it was found that 0.3 mL of 1 mg/mL aqueous solution of Ag and GO resulted in this hydrogel system presenting the highest mechanical properties and moderate water vapor permeability.).

Fourier transforms infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

Dried small block hydrogel samples (approximately 6 × 6 × 6 mm3) along with the reagents used in their preparation were analyzed by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (Bruker Alpha, Karlsruhe, Germany) in the wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm−1. This analysis helped identify the characteristic functional groups and chemical bonds in the samples.

Apparent morphological analysis of hydrogels

In the gelatin group, gelatin/Ag, gelatin/GO and gelatin/Ag/GO groups, the hydrogels were freeze-dried and observed with a field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) (JSM-7100F, Tokyo, Japan) with an accelerating voltage of 10 kV.

Water vapor permeability

The water vapor permeability was calculated by sealing the orifice of a centrifuge tube (1.22 cm2) containing 4.5 mL of deionized water with eight sets of samples (n = 6). The centrifuge tube was placed in a drying oven at 37 °C, and the mass reduction was measured to calculate the evaporated mass of deionized water. Finally, the water vapor transmittance (WVTR) was calculated using Eq. (1), where WLOSS is the reduced mass of deionized water, A is the orifice area and T is the time.The method of measurement is defined or adapted from the ASTM (formerly American Society for Testing and Materials) standard: ASTM E96.

Mechanical property

The mechanical properties of the eight hydrogel sample groups (rectangular shape, 40 mm length, 8 mm width and 0.5 mm thickness) were measured using a universal mechanical tester (Dynamic and Static Fatigue Tester Instron 5544, Dongguan, China) at a speed of 40 mm/min at ambient temperature (n = 6). The initial length, width and thickness of the samples were recorded as l0, w0 and t0, respectively.

After the measurements, data was recorded. The maximum tensile strain, tensile Young’s modulus and maximum tensile stress of the material were represented in Eqs. (2), (3) and (4), respectively. Experimental method is defined or adapted from ASTM standard: ASTM F2458-05.

Photothermal effects in vitro

In the groups of gelatin group, gelatin/Ag, gelatin/GO and gelatin/Ag/GO, four sets of hydrogel samples were soaked in 100 μL of PBS and irradiated with a 0.01 W 808 nm NIR laser (BWT, Beijing, China) for 300 s. The temperature changes were recorded using a thermal imaging camera.

Infrared bacterial inhibition performance

Initially, solid (0.12 g beef paste, 0.4 g tryptone, 0.2 g NaCl, 0.8 g agar and 40 mL deionized water) and liquid (agar-free) media were prepared. Bacteria were then added to the liquid media to create a bacterial suspension (testing Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus). Subsequently, bacterial density was measured by dilution, and the concentration was adjusted to 5 × 103 CFU/mL.

In the groups of gelatin, gelatin/Ag, gelatin/GO and gelatin/Ag/GO, we investigated whether silver in the hydrogel system could notably enhance bacterial inhibition: 0.018–0.0185 g of each hydrogel was taken and soaked in 350 μL of the bacterial suspension for each group. The samples were then incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Post incubation, 100 μL of the extract was plated on solid medium, and the number of colonies was counted after 20 h (n = 3).

Further exploration determined if GO could enhance the infrared bacteriostatic properties of the hydrogels:

Each hydrogel was immersed in liquid media for 30 min and then shaped into discs 6 mm in diameter. These discs were then soaked with 100 μL of bacterial suspension and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. Following this, the samples were irradiated with 808 nm near-infrared light (0.01 W, duration 5 min) while temperature changes were monitored. The irradiated suspension was diluted fivefold, and 50 μL was spread on solid media. The number of colonies was observed after 20 h (n = 3).

Statistical methods

Experimental values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, with graphs generated using Origin software. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with SPSS statistical software to determine differences between groups. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Hydrogel formation (gelatin/kaolin 0, gelatin/kaolin 0.2, gelatin/kaolin 0.4 and gelatin/kaolin 0.6)

The four groups of hydrogels gelled within 5 days. The hydrogels became viscous and non-flowing, as depicted in Fig. 2a. The color of the hydrogel samples progressively tended towards opalescence with increasing amounts of kaolin, and a slight increase in viscosity was observed.

Infrared spectrum (gelatin/kaolin 0, gelatin/kaolin 0.2, gelatin/kaolin 0.4 and gelatin/kaolin 0.6)

Figure 2b displays the infrared spectrum of the raw materials and the four hydrogel samples. The characteristic peaks include: Gelatin: 1626.20 cm−1 (C–O stretching vibration peak) and 1570.79 cm−1 (amide II band: C–N stretching vibration or N–H bending vibration); Sodium polyacrylate: 1457.93 cm−1 (C–O symmetric stretching vibration peak); Glycerol and propylene glycol: 3305.75 cm−1 (peaks of conjugated –OH vibration) and 1041.38 cm−1 (peaks of C–O stretching vibration); Polyethylene glycol: 3453.08 cm−1 (peaks of –OH hydroxyl stretching vibration), 2864.01 cm−1 (peaks of –CH2 methylene symmetric stretching vibration) and 1100.57 cm−1 (peaks of –C–O–C unsymmetric stretching vibration); Kaolin: 1079.51 cm−1 (Si–O stretching vibration peak) and 813.75 cm−1 (Si–O–Mg/Al stretching vibration peak).

The infrared spectrum showed that no new characteristic peaks were produced, indicating that all components were physically mixed.

Water vapor permeability (gelatin/kaolin 0, gelatin/kaolin 0.2, gelatin/kaolin 0.4 and gelatin/k-aolin 0.6)

Figure 3a shows a histogram of the water vapor permeability of four groups of kaolin samples with different masses. When holding the initial volume of deionized water constant, the water vapor transmittance of the hydrogel samples were measured as follows: 5710 ± 291 g/m2/day, 6252 ± 485 g/m2/day, 4249 ± 311 g/m2/day and 3845 ± 197 g/m2/day, respectively, after the same duration. According to studies by other researchers on gelatin-based hydrogels, their water vapor transmission rates ranged from 1832 to 1963 g/m2/day29. The transmission rates observed in this study were significantly higher than those reported in the literature, suggesting that kaolin enhances the air permeability of the samples. However, an ideal wound dressing should control water loss from the wound at an optimal rate to prevent excessive dehydration, typically recommended to be between 1800 and 2300 g/m2/day30. The results from this study significantly exceed this range, indicating a need for improvement in the hydrogel formulation.

Figure 3b presents a curve showing the mass change due to water vapor evaporation from kaolin-loaded samples across four groups. Despite the same initial volume of deionized water, the volume of water in the centrifuge tubes decreased at a consistent rate over time. The decline rates of water in the first and second groups were similar, as were those in the third and fourth groups. With an increase in kaolin mass, the decline rates in the last two groups were lower than in the first two. This phenomenon is likely because gelatin-based hydrogels contain many pore-like structures, and the introduction of kaolin as a shaping filler increases the cross-linking density among the short molecular chains, thereby reducing pore size and affecting water vapor transmission31.

Mechanical property (gelatin/kaolin 0, gelatin/kaolin 0.2, gelatin/kaolin 0.4 and gelatin/kaolin 0.6)

Figure 4a displays a histogram illustrating the tensile Young’s modulus of hydrogel samples loaded with kaolin at masses of 0, 0.2 g, 0.4 g and 0.6 g. The tensile moduli were recorded as 3.04 ± 0.01 kPa, 5.81 ± 0.03 kPa, 6.94 ± 0.03 kPa and 8.36 ± 0.01 kPa, respectively. With increasing kaolin mass, there was a gradual increase in the tensile modulus, indicating improved mechanical properties compared to the gelatin-based hydrogel without kaolin.

Figure 4b is a curve graph showing the tensile stress–strain for hydrogels loaded with 0, 0.2 g, 0.4 g and 0.6 g of kaolin. The maximum tensile strain of the samples reached 750%, and the tensile strength increased progressively with the addition of kaolin. The highest tensile strength was observed in the hydrogel loaded with 0.6 g of kaolin, demonstrating that kaolin loading enhances the tensile strength of the hydrogel.

Combining the results from various tests, the addition of kaolin enhanced the mechanical properties of the hydrogels. By comparing the hydrogel properties of different kaolin qualities, it was found that the gelatin/kaolin 0.4 g sample had a good water vapour permeability along with a significant enhancement in mechanical properties. Therefore, in this study, 0.4 g of kaolin was selected for further experimentation with the next hydrogel formulations.

Infrared spectrum (gelatin group, gelatin/Ag, gelatin/GO and gelatin/Ag/GO)

Figure 5 presents the infrared spectrum of four hydrogel samples: gelatin group, gelatin/Ag, gelatin/GO and gelatin/Ag/GO. In these four hydrogel samples, the characteristic peaks of the raw materials (gelatin, sodium polyacrylate, glycerol, polyethylene glycol, propylene glycol and kaolin) were basically the same as those in 3.2. Moreover, no new characteristic peaks appeared in the infrared spectrum, which indicates that GO and Ag did not have chemical reactions with other raw materials.The characteristic peaks of each raw material were clearly reflected in the infrared spectrum, indicating that the components were well physically mixed.

Apparent morphology (gelatin group, gelatin/Ag, gelatin/GO and gelatin/Ag/GO)

Figure 6 depicts the appearance of the four sets of hydrogel samples, from left to right, gelatin group, gelatin/Ag, gelatin/GO and gelatin/Ag/GO. All hydrogels appeared non-flowing, progressively darker in color, and exhibited a certain level of wetness and viscosity. In addition to this, all samples were snapped out using the same mould, and it can be observed that with the addition of Ag and GO, the hydrogels exhibited different degrees of shrinkage, especially after the addition of GO, the hydrogels became drier. When placed in the room temperature laboratory, all hydrogels were able to remain as in Fig. 6 all the time and maintain a certain degree of wetness.

SEM graphs of the four hydrogels are shown in Fig. 7. From the figure, it can be seen that the apparent morphology of all four hydrogels showed a roughly uniform three-dimensional mesh structure, which further proved the formation of hydrogels. The formation of the mesh may be due to the adhesion of the precursor components of the hydrogels during the stirring preparation process. The addition of nano-Ag and GO did not significantly change the apparent morphology and mesh structure of the hydrogels, and the meshes of all hydrogels were irregular, suggesting that there were no strong interactions between the nano-Ag and GO and the other components of the hydrogels affecting the crosslink density. No obvious particles of nano-Ag and GO were observed in the b-d plots, indicating that both have been completely embedded in the hydrogel matrix.

Water vapor permeability (gelatin group, gelatin/Ag, gelatin/GO and gelatin/Ag/GO)

Figure 8 illustrates a histogram of the water vapor permeability of the four hydrogel samples. The water vapor transmittance of the four hydrogels were 1903 ± 311 g/m2/day, 1898 ± 342 g/m2/day, 2112 ± 382 g/m2/day and 1776 ± 209 g/m2/day, respectively, and there was no statistically significant difference between them, which indicated that the incorporation of Ag and GO did not significantly change the water vapor permeability of the hydrogels. The water vapor transmittance of the four hydrogels was roughly in the range of 1800–2300 g/m2/day30, which is an ideal water vapor permeability for wound dressings.

Mechanical property (gelatin group, gelatin/Ag, gelatin/GO and gelatin/Ag/GO)

Figure 9a shows the tensile Young’s modulus of the four hydrogels, measured as 27.18 ± 7.36 kPa, 23.97 ± 2.83 kPa, 27.58 ± 2.90 kPa and 25.06 ± 1.06 kPa, respectively. There was no statistical difference between the four groups of hydrogels, indicating that Ag and GO did not significantly alter the tensile Young’s modulus of the hydrogels and they all exhibited high mechanical properties.

Figure 9b illustrates the stress–strain line graph of the four hydrogels with the same trend. Compared to the gelatin group, the gelatin/Ag group showed a decrease in both fracture stress and fracture strain. It can be obviously seen that the addition of GO increased the fracture stress along with the fracture strain of the hydrogel, in which the maximum fracture stress reached 51.16 kPa and the maximum fracture strain reached 1152.78%, indicating that GO can slightly enhance the mechanical properties of the present hydrogel system. This also suggested a synergistic effect between GO and kaolin in enhancing the mechanical properties of hydrogels.

The mechanical strength of an ideal wound dressing should match the mechanical properties of human skin, which has a Young’s modulus ranging from 1 to 10 kPa32, and the wound dressing should have a similar Young’s modulus, high tensile strength and fracture strain. The tensile strength, fracture strain and Young’s modulus of common hydrogel wound dressings are in the range of 25–344.5 kPa, 364–2200% and 1.9–36 kPa32,33,34,35,36, respectively, whereas the maximum tensile strength, fracture strain and Young’s modulus of the hydrogel in the present study are 51.16 kPa, 1152.78% and 27.58 kPa, which show a Young’s modulus close to that of human skin, with high mechanical properties relative to common hydrogel wound dressings.

Infrared warming performance (gelatin group, gelatin/Ag, gelatin/GO and gelatin/Ag/GO)

As depicted in Fig. 10, the photothermal conversion ability of the gelatin/Ag was slightly higher than that of the gelatin group. In contrast, the addition of GO significantly improved the photothermal conversion ability of the two groups of hydrogels, which corroborates the ability of GO to enhance the photothermal effect of hydrogels20. Among them, the photothermal conversion ability of the gelatin/Ag/GO was significantly higher than that of the gelatin/GO, and we speculate that there is a synergistic photothermal effect between Ag and GO, which will be discussed later.

Infrared bacterial inhibition performance (gelatin group, gelatin/Ag, gelatin/GO and gelatin/Ag/GO)

Initially, we investigated whether Ag could enhance the bacteriostatic properties of the hydrogel. Figure 11 displays the colony counts of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus after 20 h of incubation. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups. Both the gelatin/Ag and gelatin/Ag/GO groups did not exhibit notable bacterial inhibition, suggesting that Ag did not significantly enhance the bacteriostatic performance of the hydrogel in this system. We hypothesize that the limited overall content of Ag37 and its encapsulation within the hydrogel matrix, which may hinder its release38, could be reasons for the observed lack of significant bacteriostatic performance.

Subsequently, we examined whether GO could enhance the infrared bacteriostatic properties of the hydrogels. Figures 12 and 13 present the colony counts of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus, respectively, alongside graphs depicting the infrared warming of the hydrogels. The results clearly show that the gelatin/GO group exhibited significantly improved infrared bacterial inhibition compared to the control group. This indicates that GO indeed enhanced the photothermal performance of the hydrogel39, enabling it to convert light energy into heat more effectively and thereby achieve better bacterial inhibition. The gelatin/Ag/GO group demonstrated even stronger infrared bacterial inhibition, which we speculate is due to a synergistic photothermal effect between the nano-Ag and GO composites40. This synergy likely contributes to stronger photothermal conversion and consequently more effective infrared bacterial inhibition. These findings align with other research on the photothermal antimicrobial applications of GO-Ag nanocomposites41.

Although there was a slight warming of the gelatin/Ag over the gelatin group, it was not enough to kill the bacteria, so it did not show bacteriostatic property, which resulted in no statistical difference between the two groups. From the infrared warming graphs of the hydrogels, it is evident that the gelatin/Ag/GO group reached the highest temperature among all groups, supporting our hypothesis that Ag and GO composites may have a synergistic photothermal effect.

Compared with previous published work, the Ag/GO composite hydrogel in this study exhibited high tensile properties in terms of tensile strength, fracture strain and Young’s modulus32,33,34,35,36, while the composite hydrogel possessed excellent infrared antibacterial properties due to the synergistic effect of nano-Ag and GO41.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed novel composite hydrogels based on gelatin/sodium polyacrylate/kaolin by incorporating nanosilver and GO. Infrared spectroscopy confirmed that the hydrogel successfully incorporated all the raw materials. The addition of kaolin enhanced the water vapor permeability of the gelatin-based hydrogels. Although water vapor permeability decreased with increasing kaolin content, it remained at a high level overall. Moreover, increasing the kaolin content significantly enhanced the tensile mechanical properties of the hydrogels. Selecting 0.4 g of kaolin for subsequent experiments, we found that the inclusion of nano-Ag and GO did not significantly affect the water vapor permeability and tensile Young’s modulus of the hydrogels, but GO elevated the maximum fracture stress and strain of the hydrogels to 51.16 kPa and 1152.78%. Additionally, GO notably improved the photothermal conversion ability of the hydrogel, facilitating more efficient conversion of light energy into heat and thus enhancing bacterial inhibition performance. We also discovered a potential synergistic photothermal effect between nano-Ag and GO, which contributed to stronger infrared bacterial inhibition. In summary, we developed a composite hydrogel with excellent mechanical properties and infrared bacteriostatic properties. From the scientific level, the development of this hydrogel further expands the boundaries of our knowledge of the application potential of hydrogel materials in the biomedical field, and lays a solid foundation for subsequent in-depth research. In terms of practical value, it can be processed into various forms of skin dressings, which can be widely used in clinical wound care, such as the treatment of burns, wounds, chronic ulcers and other wounds, effectively reducing the risk of infection, accelerating the process of wound healing, and alleviating the pain and medical burden of patients. In conclusion, this achievement not only provides a powerful technical support for the research and development of novel antimicrobial skin dressings, but also brings a brand new application idea and solution for the field of wound therapy.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Peng, W. et al. Recent progress of collagen, chitosan, alginate and other hydrogels in skin repair and wound dressing applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 208, 400–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.03.002 (2022).

Luneva, O., Olekhnovich, R. & Uspenskaya, M. Bilayer hydrogels for wound dressing and tissue engineering. Polymers 14, 3135. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14153135 (2022).

Morales-Gonzalez, M. et al. Insights into the design of polyurethane dressings suitable for the stages of skin wound-healing: A systematic review. Polymers 14, 2990. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14152990 (2022).

Dong, R. & Guo, B. Smart wound dressings for wound healing. Nano Today 41, 101290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nantod.2021.101290 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Current progress and outlook of nano-based hydrogel dressings for wound healing. Pharmaceutics 15, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15010068 (2022).

Ghomi, E. R. et al. Wound dressings: Current advances and future directions. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 136, 47738. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.47738 (2019).

Zhang, T., Liu, F. & Tian, W. Advance of new dressings for promoting skin wound healing. J. Biomed. Eng. 36, 1055–1059. https://doi.org/10.7507/1001-5515.201811023 (2019).

Waresindo, W. X. et al. Freeze-thaw hydrogel fabrication method: Basic principles, synthesis parameters, properties and biomedical applications. Mater. Res. Express 10, 024003. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/acb98e (2023).

Rather, J. A. et al. A comprehensive review on gelatin: Understanding impact of the sources, extraction methods and modifications on potential packaging applications. Food Packag. Shelf Life 34, 100945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2022.100945 (2022).

Lei, J. et al. Facile fabrication of biocompatible gelatin-based self-healing hydrogels. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 1, 1350–1358. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsapm.9b00143 (2019).

Andreazza, R. et al. Gelatin-based hydrogels: Potential biomaterials for remediation. Polymers 15, 1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15041026 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Self-healing and highly stretchable gelatin hydrogel for self-powered strain sensor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 1558–1566. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b18646 (2020).

Rajitha, K. et al. Evaluation of anti-corrosion performance of modified gelatin-graphene oxide nanocomposite dispersed in epoxy coating on mild steel in saline media. Colloids Surf. A 587, 124341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2019.124341 (2020).

Chen, H., Ren, X. & Gao, G. Skin-inspired gels with toughness, antifreezing, conductivity and remoldability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 28336–28344. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b11032 (2019).

Voo, W. P. et al. Calcium alginate hydrogel beads with high stiffness and extended dissolution behaviour. Eur. Polym. J. 75, 343–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2015.12.029 (2016).

Bai, T. et al. Kaolin/caalg hydrogel thin membrane with controlled thickness, high mechanical strength and good repetitive adsorption performance for dyes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 4958–4967. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.9b06687 (2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. Removal of dyes and Cd2+ in water by kaolin/calcium alginate filtration membrane. Coatings 9, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings9040218 (2019).

Ma, X. et al. Injectable and self-healable thermoresponsive hybrid hydrogel constructed via surface-modified graphene oxide loading exosomes for synergistic promotion of schwann cells. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 12425–12438. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.3c02125 (2023).

Olad, A. & Hagh, H. B. K. Graphene oxide and amin-modified graphene oxide incorporated chitosan-gelatin scaffolds as promising materials for tissue engineering. Compos. Part B 162, 692–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.01.040 (2019).

Tang, S., Liu, Z. & Xiang, X. Graphene oxide composite hydrogels for wearable devices. Carbon Lett. 32, 1395–1410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42823-022-00402-1 (2022).

Han, J. et al. Degradable go-nanocomposite hydrogels with synergistic photothermal and antibacterial response. Polymer 230, 124018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2021.124018 (2021).

Chronopoulou, L. et al. Biosynthesis and physico-chemical characterization of high performing peptide hydrogels@graphene oxide composites. Colloids Surf. B 207, 111989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.111989 (2021).

Gu, Y. et al. Fabrication of gelatin methacryloyl/graphene oxide conductive hydrogel for bone repair. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. E. 34, 2076–2090. https://doi.org/10.1080/09205063.2023.2217063 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. High strength graphene oxide/polyvinyl alcohol composite hydrogels. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 10399–10406. https://doi.org/10.1039/C0JM04043F (2011).

Fan, Z. et al. A novel wound dressing based on ag/graphene polymer hydrogel: Effectively kill bacteria and accelerate wound healing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 3933–3943. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201304202 (2014).

Sivaselvam, S. et al. Rapid one-pot synthesis of PAM-GO-Ag nanocomposite hydrogel by gamma-ray irradiation for remediation of environment pollutants and pathogen inactivation. Chemosphere 275, 130061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130061 (2021).

Yang, S. et al. Microwave synthesis of graphene oxide decorated with silver nanoparticles for slow-release antibacterial hydrogel. Mater. Today Commun. 31, 103663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2022.103663 (2022).

Huang, H. et al. An excellent antibacterial and high self-adhesive hydrogel can promote wound fully healing driven by its shrinkage under NIR. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 129, 112395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2021.112395 (2021).

Jantrawut, P. et al. Fabrication and characterization of low methoxyl pectin/gelatin/carboxymethyl cellulose absorbent hydrogel film for wound dressing applications. Materials 12, 1628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12101628 (2019).

Xu, R. et al. Controlled water vapor transmission rate promotes wound-healing via wound re-epithelialization and contraction enhancement. Sci. Rep. 6, 24596. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24596 (2016).

Mushtaq, F. et al. Preparation, properties and applications of gelatin-based hydrogels (GHs) in the environmental, technological and biomedical sectors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 218, 601–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.07.168 (2022).

Huangfu, Y. et al. Skin-adaptable, long-lasting moisture and temperature-tolerant hydrogel dressings for accelerating burn wound healing without secondary damage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 59695–59707. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c18740 (2021).

Yuyu, E. et al. Multi-functional gleditsia sinensis galactomannan-based hydrogel with highly stretchable, adhesive and antibacterial properties as wound dressing for accelerating wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 283, 137279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.137279 (2024).

Yang, L. et al. One-pot preparation of skin-inspired multifunctional hybrid hydrogel with robust wound healing capacity. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 9, 5855–5870. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.3c00590 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Tunicate cellulose nanocrystal reinforced multifunctional hydrogel with super flexible, fatigue resistant, antifouling and self-adhesive capability for effective wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 277, 134337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134337 (2024).

Lan, G. et al. Highly adhesive antibacterial bioactive composite hydrogels with controllable flexibility and swelling as wound dressing for full-thickness skin healing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 785302. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2021.785302 (2021).

Abdel-Halim, E. S. & Al-Deyab, S. S. Antimicrobial activity of silver/starch/polyacrylamide nanocom-posite. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 68, 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.04.025 (2014).

Tanwar, A., Date, P. & Ottoor, D. ZnO NPs incorporated gelatin grafted polyacrylamide hydrogel nanocomposite for controlled release of ciprofloxacin. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 42, 100413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colcom.2021.100413 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Research progress on the biomedical uses of graphene and its derivatives. New Carbon Mater. 36, 779–791. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1872-5805(21)60073-2 (2021).

Cao, X. et al. BC/GO-Ag composite aerogel with synergistic enhanced photothermal performance for efficient solar water evaporation. Sol. Energy 255, 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2023.03.022 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Photothermal-assisted antibacterial application of graphene oxide-Ag nanocomposites against clinically isolated multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 192019. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.192019 (2020).

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China 12002232, National Natural Science Foundation of China 22278291 and Natural Science Foundation of Shanxi Province 202203021211145.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L., Z.W., S.L. and Y.F.L.; methodology, Y.L., L.W., D.W. and Z.D.; validation, Y.L., L.W., D.W. and Z.D.; formal analysis, Y.L., L.W. and D.W.; investigation, Y.L., L.W. and D.W.; resources, Y.L., Z.W., S.L. and Y.F.L.; data curation, Y.L., L.W. and D.W.; writing-original draft preparation, D.W.; writing-review and editing, Y.L. and D.W.; visualization, Y.L., L.W. and D.W.; supervision, Y.L., L.W. and D.W.; project administration, Y.L., Z.W., S.L. and Y.F.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L. and Y.F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Wang, L., Wen, D. et al. Preparation and characterization of nano-silver/graphene oxide antibacterial skin dressing. Sci Rep 15, 12490 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93310-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93310-z