Abstract

The presence of toxic chemicals in sewage has implications for human health but evidence is lacking. The current study aimed to delineate the state of pollution of sewage water in Ukraine before the full-scale Russian invasion in 2022. Ten sampling locations around the country were selected, varying by population and industry level. We used inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) to analyse Aluminium, Cadmium, Copper, Iron, Manganese, Nickel, Lead and Zinc concentrations in the sewage water. Sewage water samples from Kharkiv and Lviv showed 100 to 1000 times higher levels of heavy metals than considered safe. It is shown that samples from high urban and industrial regions have significantly higher levels of pollutants than in other cities. The concentration of metals in water samples collected in the evening was higher than the morning of the same day. Furthermore, there was a marked increase in levels of metals on weekdays compared to weekends. The anomalous increases coincided with peak times of large factory operations/works. Our results have significant implications for authorities responsible for environmental health at regional, national, and international levels, given the implications for water consumers in Ukraine. During the post-war rebuilding, sewage water treatment improvement should be prioritised.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Providing nationwide high-quality water is one of the leading environmental safety challenges for sustainable development. When speaking of Ukraine, its legislation system considers drinking water and sewage water as standalone water supply system with no specific acts related to sewage water or its treatment.

Ukraine has a full set of authorised executive bodies to control the condition of water sources, including control over the quality and quantity of sewage water drained into sewerage. However, only limited and fragmented monitoring data of water quality control including sewage water is available1,2,3 because of the variation between different authority bodies’ procedures. Therefore, it is not clear how regulatory bodies and frameworks interact between authorities, consumers, and sewerage companies to affect the water consumed by end users across the country.

Moreover, research monitoring appears not to have been undertaken for establishing the main anthropogenic impacts on the quantitative and qualitative content of water sources, which facilitates: (a) establishment of the reasons for deviations from environmental goals, (b) clarifications of the scale and consequences of accidental water pollution and (c) an understanding of the sources of risk for failing to achieve the environmental goals identified in the process of diagnostic monitoring before the operational monitoring starts4.

Accordingly1, the current state of the sewage water treatment network in Ukraine may be enhanced in larger urban compared with rural areas, which show low ratios for centralized water supply and sewage water treatment systems (Table 1).

This indicates that a proportion of Ukrainian water consumers could drain polluted water back into the environment with no control over its pollution level. The quality and safety of public drinking water are of utmost importance to population-level human health5. With evidence of pollutants such as Lead (Pb) and Cadmium (Cd) incurring health risks6,7, the uncertain composition of Ukrainian water sources is a concern.

According to the 2022 Ukraine national report on drinking water, the country has about 2,500 water supply and sewerage service companies, with 700 of them providing central services, including 140 companies in cities with a population of less than 100,000 people and 46 companies in big cities with a population of over 100,000.

In total, sewage treatment covers almost 97.5% of total sewage water, with 90.5% of treated wastewater undergoing full biological purification and 3.5% undergoing additional treatment procedures.

As it is very expensive to maintain all indicators at a suitable level, many countries are engaged in step-by-step improvements as permitted by economic and infrastructure factors. However, Ukrainian investment in sewage water has been decreasing over the last 15 years, from 162 million USD in 2007 to 62 million USD in 20198. Thus, recently, the wear level of water supply infrastructure reached more than 50%, with some cases more than 70%1.

The situation declined after February, 24 2022. According to the 2024 Rapid Needs Assessment and Damage Assessment9, between February 2022 and December 2023, the water and wastewater sector in Ukraine suffered losses of about USD 4 billion, with the most significant losses recorded for large physical water and wastewater infrastructure. The financial losses of the sector are estimated at USD 11.6 billion, with 40% of the losses attributed to revenue losses due to reduced water consumption and 30% to increased energy costs.

The overarching aim of the current study was to examine the state of sewage water pollution in all major urban areas (except the Donbass region) of Ukraine.

Our three main objectives were as follows. Our first objective was to examine the concentration of key metals in ten cities of Ukraine. As well as toxic metals (Pb, Cd), other potentially harmful metals were assessed: Aluminium (Al), Copper (Cu), Iron (Fe), Manganese (Mn), Nickel (Ni), and Zinc (Zn). Secondly, to account for temporal and geographical water consumption differences, we compared morning and evening concentrations of pollutants in sewage water in industrial and non-industrial regions.

Thirdly, it was anticipated that this experimental data could provide signals relating to possible approaches for upgrading sewerage systems in Ukraine, thereby protecting the environment and, ultimately, human health. Given the recent devastating impacts on the water supply system in Ukraine, the current study now serves as a snapshot of the sewage water quality in Ukraine in the pre-war era. However, this provides a vital baseline for the post-war rebuilding.

Materials and methods

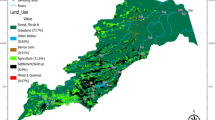

Geographical sampling

Geographically diverse cities were selected from around Ukraine, from West (Uzhhorod, Lviv) to East (Kharkiv, Sumy) and North (Kyiv) to South (Kherson). In total, ten cities were selected for this study, with populations varying from 115,500 in Uzhhorod to 3 million in Kyiv, according to the State Statistics Service of Ukraine data on the population as of January 1, 202210, see Supplementary Figure S1.

Most cities were categorised as small (population < 500,000), with two medium (500,000–1,000,000; Lviv and Zaporizhzhia) and two large (> 1 million; Kharkiv and Kyiv).

To interpret the industry level of the selected locations, we used the State Statistics Service of Ukraine data on the proportion of people working in industry11 [Table 2.2] shown in Supplementary Figure S2.

The ten regions focused on can be divided into high industry level (> 20%; Zaporizhzhia, Kharkiv and Lviv), average industry level (15–20%; Cherkasy, Sumy, Uzhhorod and Kropyvnytskyi) and low industry (< 15%; Ternopil, Kherson and Kyiv).

Sewage sampling

All samples were collected in 2021 between September 29th and October 31st by local water supply agency representatives running sewerage systems.

For each site, a 7-day period without precipitation was ensured before the sampling procedure proceeded due to potential contamination of water samples by rainwater flushes. If rainy weather began in the city where samples were being sequentially collected, a pause was made, and sampling resumed one week after the rain had ended. For each local water supply and sewerage enterprise, the sampling procedure lasted for 7 consecutive days with two samples (morning and evening) per day. Sampling of sewage water was conducted upon its arrival at the treatment facilities (entry collective chamber). Each sample contained 250–500 mL of collected sewage water added with 1 mL of concentrated nitric acid to prevent any unnecessary biochemical reactions from occurring. Sample tubes were then sealed and sent to the State Scientific Institution “Institute for Single Crystals” (Kharkiv, Ukraine) for further analysis. Most locations had a single sewage water system; only Lviv and Kharkiv had two, and thus, both were sampled.

In total, 168 sewage water samples were analysed for Al, Cd, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, Pb and Zn content.

The data of the industrial waste ratio in total wastewater volume as well as the sampling site description along the locations is given in Supplementary Table T1.

A large difference is observed in the urban sewage system involvement in the collection of the industrial wastes among the selected locations. While Kharkiv, Lviv, Zaporizhzhia and Sumy wastewater treatment plants receive a large volume of industrial wastes from 40 to 80%, while other locations receive no more than 30%.

This indicates two approaches to industrial wastewater treatment currently used in Ukraine, either the centralized collection at urban area wastewater treatment plants or the consumer on-site collection and purification. The large volume of industrial wastes in the small Sumy agglomeration is explained by the presence of the big chemical Enterprise “Sumykhimprom”, which produces dozens of hundreds of tons of titanium oxide and other chemicals, and is the one main water consumer in the city.

Analytical methods and instrumentation

Deionised water was obtained from P. Nix. Power II System by Human Corporation (Seoul, Korea), the certain metal certified reference materials (CRM) for calibration were purchased from A.V. Bogatsky Physico-Chemical Institute NASU (Odessa, Ukraine), the concentrated nitric acid was obtained from Merck, KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany).

Measuring procedure

Metals concentrations in the prepared solutions were measured by means of inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) using iCAP 6300 Duo ICP Spectrometer (Thermo Scientific Corporation, USA). To develop calibration curves, the mixtures with element concentrations of 0.01, 0.1 and 1 mg/L were prepared by the dilution of a respective metal CRM. The operation conditions were as follows: RF Power – 1150 W, plasma carrier gas flow – 14 L/min, auxiliary gas flow – 1 L/min, solution uptake – 1.85 mL/min, nebuliser – glass conical, “Sea Spray” (Glass Expansion, Australia).

Calibration

Calibration parameters from Table 2 show excellent linear dependency between the analytical signal and the concentration of analyte for each studied metal.

The comparison of the regulatory requirements in the EU and Ukraine regarding the content of the target elements in the sewage water is given in Table 3. EU regulations appear stricter than Ukrainian.

Results

To address the discussion of sewage water compliance with regulation requirements hereafter authors use ‘Me: MPC’ indicator on figures, estimated as ratio of found metal concentration to its correspondent MPC value (Table 3), e.g. \(\:Me:MPC=\:\frac{{c\left(metal\right)}_{found}}{MPC\left(metal\right)\:}\). The sample with \(\:Me:MPC\ge\:1\) was recognized not to comply with correspondent regulation.

Zinc, Nickel, Manganese and Copper

These elements are grouped as the main indicators of industry level in the sample region that may affect the total sewage water quality (Fig. 1).

All of the studied samples except from Zaporizhzhia had lower zinc content than the MPC level in Ukraine. Higher Zinc levels were found in cities that were either large non-industrial (Kyiv) or industrial cities of medium or large size (Zaporizhzhia, Kharkiv, Lviv). Levels of Manganese, Nickel and Copper were lower than their MPC level overall (although only Manganese had no samples exceeding the MPC; see Supplementary Table T2). Manganese was highest in Lviv (medium, industrial), followed by Zaporizhzhia (medium, industrial) and Kropyvnytskyi (small, medium industry). Nickel levels were not clearly related to industry or city size, with the highest levels derived from Kharkiv (large, industrial), Zaporizhzhia (medium, industrial) and Uzhhorod (small, medium industry). Copper was highest in Kharkiv and Lviv (both medium-large industrial cities). Overall, the lowest concentrations of these four metals were observed in the Kherson, Cherkasy and Ternopil regions (all low population areas, most with low industry levels).

Compared to stringent EU regulations, the average Zinc concentration was found to exceed the MPC level in Zaporizhzhia, Kharkiv, Lviv, Kyiv, Kropyvnytskyi, and Cherkasy, while Nickel was higher in Zaporizhzhia, Kharkiv, and Uzhhorod. The average Copper concentration was higher than its MPC level in Kharkiv and Lviv.

Compared to the concentrations of metals found in municipal waste water treatment plants in EU countries17,18, found metal levels exceed those in the EU considering there were no samples with metal level below the limit of detection.

Aluminium, Iron

Metals with traditionally higher content compared to those previously mentioned can also be indicators of the water pollution level by heavy industry. The highest Iron level was in Zaporizhzhia (medium size, high industry), which was 4–6 times higher than samples in Kherson or Cherkasy (small; see Fig. 2). Conversely, samples from Ternopil and Uzhhorod show higher Iron levels than can be expected from low-industrial areas.

Only three regions did not have any samples exceeding the Iron MPC (Cherkasy, Kherson, Ternopil), whereas the maximum Kharkiv level exceeded the MPC by almost three times (Supplementary Table T3). Compared to the concentrations of metals found in municipal waste water treatment plants in EU countries17,18, found Aluminium levels all over studied locations exceed a lot of those found in EU while Iron wasn’t even of interest.

Many other Iron concentrations were higher than the MPC, most unexpectedly from Kropyvnytskyi (small, medium industry), which was higher on average than Lviv and Kharkiv (medium/large, and industrial). Levels were particularly low for Kherson and Cherkasy (small, low/medium industry).

All samples had Aluminium content below MPC for sewage water, with the lowest content similar to that of the Kherson and Cherkasy regions.

Compared to strict EU regulations (Fig. 3B), Aluminium was still low for all samples, while average Iron was high only for Zaporizhzhia.

Lead, Cadmium

Both are considered toxic, with concerns regarding accumulation and chronic effects on human health and likely linked to high-urban or heavy industry areas19.

Except for the anomaly samples discussed below, Pb and Cd levels correlate with the industry level of the sampling location, as larger cities with heavy industry have higher concentrations of these metals in the sewage water (Fig. 2C,D). Similar to the above, the lowest content for these two metals was found for the Kherson and Cherkasy regions (Supplementary Table T4). Most levels were below their MPC level both for Ukrainian and EU regulations, except for single anomalies from Kharkiv (Cadmium) and Lviv (Lead), however, both metals weren’t detected in a large survey of municipal waste water treatment plants in EU countries18.

Sewage water quality in Ukraine compared to National and EU regulations

Our results show that the quality of sewage water in Ukraine is relatively low, as 7 of 10 studied locations’ samples have contained one or more metals above safe and recommended MPC levels.

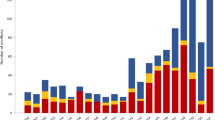

To obtain a wider perspective, we counted observations of metal content exceeding their MPC levels both according to UA and EU regulations, grouped by cities, as shown in Fig. 4B. These grouped values can be recognized as ‘pollution scores’ – the number of times MPC levels were exceeded.

Our data show that only the quality of sewage water samples from the Kherson region complies both with Ukrainian and EU regulations (Fig. 3). However, because of the collapse of the Kakhovka dam in June 2023, the situation for Kherson has changed drastically. Considering the active battle in this region, no study of the consequences of this event on the water quality can presently be conducted in any way.

Regarding Ukrainian regulations, only Kharkiv and Lviv have samples with multiple elements above their MPC levels while other locations have only Iron to be an issue. As an essential nutrient for humans and aquatic organisms, Iron plays a crucial role in oxygen transport, metabolism, and various physiological processes. However, at excessive levels, Iron can build up in the internal organs of aquatic life leading to negative effects on the humans or creatures consuming them. In general, 21 of 1344 observations have triggered warnings.

However, in the case that Ukraine was to adopt strict EU regulations for sewage water quality, the situation would become concerning (Fig. 3).

Compared to EU MPC levels, all studied locations except Kherson have samples with one or more metals that exceed the MPC level. While Kharkiv and Lviv remain the leading locations in terms of the number of pollution observations, Zaporizhzhia and Kyiv follow them closely.

Surprisingly, Zinc and Copper appear most concerning, covering 75% of all warning observations, whereas Iron pollution remains at low levels. Although Zinc is essential for humans and aquatic organisms, playing roles in enzymatic functions and growth, its excessive levels can harm aquatic life and ecosystems. Copper is also an essential trace element for both humans and aquatic organisms, required for various enzymatic functions. However, high levels of Copper can be toxic, particularly to aquatic organisms, and lead to impaired reproduction and growth.

Samples from half of the locations contained excessive levels of Nickel. This pollutant of industry origin can have adverse health effects on humans, particularly respiratory issues and skin sensitization. In aquatic environments, Nickel can impact aquatic organisms and affect sewage water quality.

In total, 170 of 1344 or 12% of observations may trigger warnings if we apply EU regulations.

Samples contained Aluminium below its MPC level, which is required by Ukraine and EU regulations. This metal is not considered essential for human health but is abundant in the environment.

Considering the small sampling size and only partially covered regions, the true situation with sewage water quality in Ukraine is not entirely known.

Anomaly samples

The sample from Kharkiv collected from sewage city source 1 in the evening of October 8th showed an anomalously high concentration of Al, Cd, Cu, Fe and Ni not only compared to the morning sample of the same day but for the whole sample batch of Kharkiv region. The same anomaly was found for the sample from Lviv collected from the KOC-1 city sewage source on the evening of October 6th, with high concentrations for Al, Cu, Fe, Pb, and Zn (Table 4).

Table 4 shows a 100–1000 times increase in Fe, Pb, Ni and Cu content in the evening samples of sewage water compared to the morning ones of the same day.

Weekday flow

We compared the metal content against the sampling day. Here we found two groups, with some metals having weekly fluctuations and some without. No clear pattern was evident for Iron, Aluminum, Manganese or Zinc (Fig. 4A), although Iron was relatively high on working days compared with the weekend.

Conversely, we noted a similar pattern for Cadmium, Lead, Copper and Nickel (Fig. 4B).

Copper content was higher in Thursday and Friday samples, Nickel was higher on most weekdays, Lead was higher on Wednesdays (although this may have been driven by the anomalous value discussed above), and Cadmium was higher on Fridays. Overall, then, metal concentrations were greater on working days, particularly later in the week. As Friday is the last working day in Ukraine it may be that evening sewage samples contain higher concentrations of the studied metals as a result of unauthorized draining from industrial consumers. However, this is only conjecture.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate some clear areas in need of rectification regarding sewage water systems in Ukraine. First, Ukrainian waste water treatment plants receive effluents with 5–10 higher content of metals than those in EU countries. Second, samples from high urban areas of Ukraine may contain up to 100–1000 times high concentrations of pollutants, thus requiring larger consumption of reagents and leading to the increase of degree equipment wear than it is envisaged.

According to experts, the upgrade of water treatment and sewerage systems in Ukraine requires billions of Euros, including the renovation of water supply networks and sewer systems and the improvement of wastewater treatment quality up to EU standards20. In 2015 the European Investment Bank (EIB) had already started a Ukraine Municipal Infrastructure Programme with a total budget of EUR 800 million to cover the key municipal sectors of district heating, energy efficiency in public buildings, street lighting, water and sanitation and solid waste management.

Updating water regulations to comply with EU’s is another big challenge for Ukraine as its water supply system is both outdated and destroyed by the Russian invasion; upgrades are needed before the implementation of stricter rules.

Under current conditions, Ukraine cannot afford such funding itself as current water tariffs are not sufficient to cover these expenses. The Ukrainian government had already widely recognized the importance and urgency of upgrading the water supply and sewerage companies to pursue the National Target, and the importance of the upgrades to rely highly on applying energy-saving technologies was also considered. In February 2022, right before the Russian invasion, the State Agency of Energy Efficiency and Energy Saving of Ukraine presented the Concept of the State program of energy modernization of water supply and sewerage enterprises to be run in 2022–2027.

In February 2022 the Ukrainian Parliament adopted a State Program “Drinking water of Ukraine for 2022–2026” with about €1 billion funding aimed to decrease the untreated wastewater ratio down to 3%, although the Program had not been fully signed. There were several projects being implemented to re-equip water supply services funded by the World Bank, the EIB, the EBRD, NEFCO with the total amount of $600 million, in addition to other initiatives planned to attract investments.

The Ukrainian Association of Water Supply and Sewerage ‘Ukrvodokanalekologiya’ was likely the only organisation to have not only participated in the development and implementation of modern regulations on drinking water safety and quality, but also conducted the alternative monitoring of wastewater quality to help reveal the issues.

Since initiating this project and undertaking analyses, the situation has changed drastically as of February 24th 2022. During the invasion, the heavy shelling, strikes and missiles destroyed a lot of industry sites country-wide and the water supply infrastructure in the East and South of Ukraine. The collapse of the Kakhovka dam in June 2023 would have a severe impact both on the water supply chain for many regions in Ukraine and the aquatic life itself. Now in discussing the future of water supply networks in Ukraine, we may consider the total renovation approaches rather than system upgrades. This research, however, serves as a baseline regarding the pre-war state of sewage constituents. Our data can be used as a starting point for future longitudinal studies to monitor changes during upcoming months and years.

However, during the post-war rebuilding, we need to prioritise water rebuilding, given that the previously discussed initiatives came to a halt. In addition, EIB has already drafted two Programmes, ‘Ukraine Water Recovery Framework Loan’ and ‘Ukraine Recovery III Framework Loan’21,22 with a total budget of EUR 450 million to support priority investments in the recovery of areas affected by the conflict in Ukraine and the basic infrastructure needs of Internally Displaced Persons. This seems to be only a small step in the long way of rebuilding the Ukrainian water supply system.

Limitations

The study was limited in our inability to examine drinking water or sewage water quality after treatment. The study would also have been improved by measuring a greater number of samples and/or locations, over a longer period of time.

Sample preparation

The pH value of the received samples varied between 6.5 8.5 (controlled by OHAUS Starter3100 meter) instead of being < 5, as contacted water suppliers were unable to achieve the acidic preservation procedure of wastewater samples. This led to the formation of sludge, mud and other precipitations during the delivery time.

To overcome this problem, the following steps were performed: from each sample 25 ml (15 ml from Kherson location) aliquot was taken and placed in the beaker added with 2 ml of analytical grade nitric acid (60wt.%). The obtained mixture was carefully evaporated to ~ 5 ml using a laboratory hot plate. Further, the beaker content was cooled to an ambient temperature and filtered into a 25 ml volumetric flask using ashless filter paper. The flask was filled up to the volume with deionised water.

Conclusions

The current research data represents a comprehensive study of sewage water pollution levels in Ukraine involving locations throughout the country and is the first attempt to provide a simultaneous comparison of its quality to both Ukrainian and EU regulations.

The study indicates that the quality of sewage water in Ukraine is a cause for concern and the sewage water quality situation worsens when comparing Ukrainian regulations to more stringent EU regulations. While under Ukrainian regulations, a relatively smaller number of observations trigger warnings, adopting EU standards reveals a more widespread issue.

Compared to EU requirements, a significant proportion of samples from various locations in Ukraine have been found to contain one or more metals exceeding safe and recommended maximum permission concentration levels, suggesting that heavy metal pollution is a notable problem in Ukraine’s sewage water systems with no clear evidence of high pollution by widely recognized toxic elements such as Lead or Cadmium. The two major anomalies were from Kharkiv and Lviv showing 100–1000 times increase of metal content in the evening samples of sewage water compared to the morning ones of the same day. Peak operating times of large factories may have coincided with higher metal concentrations towards the end of the working week. Lead and Cadmium levels correlated with the industry level of sampling locations with larger industrial cities having higher concentrations of these metals in the sewage water.

This indicates a necessity of upgrading the Ukrainian sewage water supply system as the spillages of polluted waste waters would negatively impact river and sea basins in Eastern Europe. Although some plans were underway right before the invasion, it is clear that now Ukraine faces a total and national reconstruction of the water supply and sewerage network to provide drinking water to its citizens. In collaborating to do so, Ukrainian and international organisations and experts will require extensive resources and action.

In planning and actioning renovations, when the time comes, our work recommends considerations of these studied pollutants and encourages the implementation of measures including standardised regular monitoring of sewage and drinking water constituents, and prevention of non-permitted industry/waste disposal into sewage or other water sources.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ministry of Infrastructure of Ukraine. National Report on the Quality of Drinking Water and the State of Drinking Water Supply in Ukraine in 2021. https://tinyurl.com/2machbmd (Ministry of Infrastructure of Ukraine, 2022).

Nikolaichuk, V. І., Vakerich, M. М. & Shpontak, J. М. Karpu’k, М. К. The current state of water resources of transcarpathia. Biosyst. Divers. 23, 116–123. https://doi.org/10.15421/011517 (2015).

Nazarov, N., Cook, H. F. & Woodgate, G. Water pollution in Ukraine: the search for possible solutions. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 20, 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/0790062042000206110 (2004).

Sorokovska, S. V. The role and place of monitoring and evaluation in the state policy in the sphere of drinking water supply. Derzhavne Upr. Udoskon. Ta Rozvyt. 354, 0–3. https://doi.org/10.32702/2307-2156-2019.4.101 (2019).

World Health Organization. Nutrients in Drinking Water. WHO, Geneva. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/51499/retrieve (World Health Organization, 2005).

Bouida, L. et al. A review on cadmium and lead contamination: sources, fate, mechanism, health effects and remediation methods. Water 14, 3432. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14213432 (2022).

Schaefer, H. R. et al. A systematic review of adverse health effects associated with oral cadmium exposure. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 134, 105243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2022.105243 (2022).

Cherenkevych, O. Statistical evaluation of efficiency of environmental measures financing in Ukraine. Ef Ekon. 0–2. https://doi.org/10.32702/2307-2105-2020.11.200 (2020).

Rapid, T. & Assessment, D. Third Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099021324115085807/pdf/P1801741bea12c012189ca16d95d8c2556a.pdf (2023).

State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Number of Present Population of Ukraine as of January 1, 2022. https://ukrstat.gov.ua/imf/arhiv/nas/nas2022_e.htm (State Statistics Service of Ukraine, Kyiv, 2022).

State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Labor Force of Ukraine in 2021. State Statistics Service of Ukraine, Kyiv, (2022). https://ukrstat.gov.ua/druk/publicat/kat_u/2022/zb/07/zb_RS_2021.pdf

Ministry of Health of Ukraine. DSanPiN 2.2.4-171-10. State Sanitary Norms and Rules ‘Hygienic Requirements for Drinking Water for Human Consumption’. https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/z0452-10?lang=en#Text (Kyiv, 2010).

European Commission Directive (EU) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2020 on the quality of water intended for human consumption. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019 (1-62). (2020).

Development, M. of R. Rules of Acceptance of Sewage from Enterprises into Municipal and Departmental Sewage Systems of the Settlements of Ukraine, Approved by Order of the Ministry of Regional Development, Construction and Housing and Communal Services of Ukraine No. 316 D. https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/z0056-18?lang=en#Text (Ministry of Regional Development, Kyiv,. 2017).

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Standard statistical classification of surface freshwater quality for the maintenance of aquatic life. In Readings in International Environment Statistics. (United Nations, New York and Geneva, 1994).

European Commission. Commission implementing decision (EU) 2018/1147 establishing best available techniques (BAT) conclusions for waste treatment, under directive 2010/75/EU of the European parliament and of the council. 48–119. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?toc=OJ:L:2018:208:TOC&uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2018.208.01.0038.01.ENG (2018).

Ida, S. & Eva, T. Removal of heavy metals during primary treatment of municipal wastewater and possibilities of enhanced removal: A review. Water (Switzerland) 13, 1121–1147. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13081121 (2021).

Loos, R. et al. EU wide monitoring survey on waste water treatment plant effluents. JRC Sci. Polic. Rep. https://doi.org/10.2788/60663 (2012).

World Health Organization. Safely Managed Drinking Water. World Health Organization (World Health Organization). https://data.unicef.org/resources/safely-managed-drinking-water/ (2017).

Swiss-Ukrainian Project, DESPRO. Water Supply and Sanitation in Ukraine. https://despro.org.ua/library/WSSPolicyPositionPaperDESPRO-EN.pdf (2020).

European Investment Bank. Ukraine Water Recovery FL. https://www.eib.org/en/projects/pipelines/all/20210112 (2023).

European Investment Bank & Ukraine Recovery, F. L. III (2023). https://www.eib.org/en/projects/pipelines/all/20230227 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This article is a collaboration between individuals at King’s College London, the Ukrainian Association of Water Supply and the State Scientific Institution “Institute for Single Crystals”.This study was supported by the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.Authors from Ukraine would like to thank the Armed Forces of Ukraine for their outstanding service and sacrifice that allowed this work to be finished and published.

Funding

This work was sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Project #0119U100727.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AY and DO conceptualised the study and were responsible for funding acquisition. VK and NM were responsible for data curation and acquisition. IS and KB conducted the formal analysis. All authors were involved in data interpretation. All authors were responsible for the study investigation/methodology. IS, MN and BS wrote the original draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscript and gave final approval for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

In the past 3 years, R.S. declares honoraria from Janssen; A.H.Y. has received honoraria for attending advisory boards and presenting lectures for Allergan, Astra Zeneca, Bionomics, COMPASS, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LivaNova, Lundbeck, Servier, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma and Sunovion, and has received consulting fees from Johnson & Johnson and LivaNova. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shcherbakov, I., Bryleva, K., Strawbridge, R. et al. Poor quality of sewage water in Ukraine: a priority in post-war rebuilding. Sci Rep 15, 23296 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93335-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93335-4