Abstract

With the increasing number of deep-buried tunnel constructions in China, the possibility of rockburst hazard during tunnel construction in high-stress, hard rock environments also rises. The stress inversion method is initially employed to determine the stress characteristics along the tunnel axis to provide the basis for predicting rockburst hazards. Then, utilizing widely recognized stress criteria and newly proposed energy criteria, the risk of tunnel rockburst hazard is predicted from macroscopic and microscopic perspectives. The results indicated that: (1) The discrepancy between stress inversion and borehole measurement data is generally within 13%, confirming the feasibility of obtaining the in-situ stress distribution characteristics of the tunnel site through stress inversion. (2) From the macro perspective, the predictive accuracies for the left and right tubes in assessing the level of rockburst hazard in the Ping’an Tunnel are 70.6% and 68.7%, respectively. The accuracy of the rockburst hazard level prediction presented in this study is approximately 70%, achieving a high reliability level. (3) From the microscopic perspective, based on the energy criterion of rockburst hazard and the energy evolution of the surrounding rock during the construction process of the Ping’an Tunnel, the specific locations where rockburst hazard can occur on the tunnel face are analyzed. This provides a vital reference for the prevention and control of rockburst hazard.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rockburst refers to a dynamic instability hazard caused by the sudden release of elastic strain energy accumulated in hard and brittle surrounding rocks after the excavation of underground engineering under high-ground stress conditions1,2,3. In recent years, as the depth of underground engineering construction has increased, accidents in hard rock tunnels under high-ground stress conditions have occurred more frequently, causing significant harm to the safety of construction personnel and equipment4,5. Therefore, based on the characteristics of the rockburst hazard, predicting high-ground stress rockburst hazard is an essential area of research in rockburst tunnel engineering.

Many researchers have conducted extensive studies on the prediction of rockburst hazard and have achieved significant results. Regarding prediction methods, the technology can be categorized into four main types: index criterion method, numerical index method, mathematical model method, and field test method. The index criterion mainly comprises the stress criterion6,7,8,9, the rockburst tendency criterion10,11,12, and the comprehensive criterion13,14,15. The indicator criterion method can be utilized to assess rockburst tendency hazard along the entire tunnel. Based on the statistical analysis of numerous rockburst cases, the stress criterion is simple to implement and has gained widespread acceptance in practical engineering due to its reliability. The numerical index rule primarily relies on energy indicators, such as energy density16, local energy release rate17, and rockburst energy release rate18. The energy changes of rocks during tunnel excavation can be calculated using finite element and discrete element software, the location of rocks with high energy around the tunnel can be identified, and the probability of rock burst disasters in the rocks can be predicted by the value of accumulated energy in the rocks. In addition, with advances in artificial intelligence, machine learning has introduced a novel approach to predicting rockburst tendencies. It utilizes black box models to illustrate the highly complex nonlinear relationship between rockburst and its influencing factors, with machine learning extensively employed for this purpose. The methods mainly include artificial neural networks19,20,21, support vector machines22,23, fuzzy mathematics methods24,25, and cloud modeling methods26,27. However, the prediction accuracy of artificial neural networks and support vector machine methods depends on the size and credibility of the training set, necessitating abundant training samples and entailing high execution difficulty and cost. In addition, fuzzy mathematical methods and cloud modeling methods are prone to subjective interference in assignment, with a certain degree of arbitrariness, making it challenging to maintain high accuracy consistently.

The on-site monitoring method predominantly focuses on microseismic monitoring. This technology can accurately predict and warn of imminent rockburst hazard by collecting and analyzing elastic wave signals during rock fracture processes and has become a pivotal means of on-site rockburst hazard prediction27,28,29,30,31. However, microseismic monitoring technology can only predict imminent rockburst hazard and cannot provide advance judgments on the risk of rockburst hazard during the design phase. Technology is essentially the result of the accumulation of rockburst energy, and a more effective prevention and control strategy involves predicting rockburst hazard through earlier prediction methods, then designing or adjusting support plans to prevent the large-scale release of rockburst energy, achieving more effective prevention and control of rockburst hazard.

In the design stage, only the indicator and numerical simulation methods are widely used and considered highly accurate for predicting rockburst disasters. Based on the size of the prediction scope, the prediction methods for rockburst disasters during the design stage can be classified into macro and micro levels. At the macro level, evaluating rockburst disasters along the tunnel alignment provides an estimate of the approximate mileage of potential rockburst occurrences, facilitates the preliminary determination of the tunnel excavation and support design scheme, and allows for calculating construction costs. At the micro level, evaluating rockburst disasters enables the prediction of specific locations of rockburst occurrences, such as at the sidewall or arch top. The micro-level prediction serves as a supplement to the macro-level evaluation. Therefore, both levels of rockburst prediction methods should be utilized to enhance the accuracy of rockburst disaster prediction.

Both methods require the acquisition of stress data from the tunnel’s surrounding rock and its mechanical properties. The mechanical properties of rock and soil are relatively easy to obtain through geological prospecting data and rock mechanical experiments, whereas the geological stress state along the tunnel axis is more complex. Currently, the most reliable method for obtaining ground stress is field measurement. However, conducting field measurements throughout the tunnel is impractical due to time, location, and cost constraints for deep-buried and super-long tunnels. Therefore, employing effective calculation and analysis methods based on limited measurement data is necessary to derive a more accurate stress field for the tunnel site area, providing a basis for predicting and preventing rock burst hazards32.

In addition, data from uniaxial compression experiments are generally utilized to analyze the tendency of rockburst disasters from an energy perspective. The typical criteria for this are listed in Table 133,34,35,36,37,38,39,40, and their basic principles are based on analyzing the energy required for rock failure in the experiment. However, the energy required for rock failure in uniaxial compression experiments differs significantly from the energy required for rock failure during actual rockburst disasters. On the one hand, when a rockburst disaster occurs, the rock is in a high-stress state, and the strength and mechanical properties of the rock vary greatly under this high-stress state. The energy absorbed by the rock is also inconsistent with that in uniaxial experiment. On the other hand, the occurrence of rockburst disasters is a process of instantaneous unloading, where the stress in one direction of the rock rapidly decreases to zero. The damage caused by instantaneous unloading is inevitably significantly different from that caused by slow loading. Therefore, certain shortcomings exist in using uniaxial compression experiments to analyze the energy conditions under which rockburst disasters occur. Considering the conditions of rockburst disasters, this study develops a well-designed experimental plan to simulate the rock instability process during rockburst hazards in laboratory settings, allowing for determining the rock’s ultimate energy storage under instantaneous unloading conditions. This provides a basis for identifying the specific locations of support structure hazards in numerical experiments.

Based on the Ping’an Tunnel of Chenglan Railway, the stress distribution characteristics along the tunnel axis were obtained using local in-situ stress measurement data. Combined with relevant criteria, this enabled an approximate prediction of the location and severity of the rockburst hazard. In addition, considering the characteristic of inducing rockburst hazard through the rapid unloading of confining pressure, a tunnel rockburst energy criterion based on unloading confining pressure experiments was proposed. The potential locations of tunnel rockburst hazard were predicted using this criterion. Rockburst hazard prediction was performed at both macro and micro levels using the abovementioned methods. The accuracy of the rockburst hazard assessment was then verified based on actual rockburst events observed on-site. These research findings can further optimize the design and construction support strategies for rockburst tunnels, which are crucial in preventing and controlling tunnel rockburst hazard.

Project overview

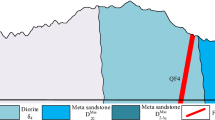

The Chenglan Railway begins in Chengdu, passing through Mao County, Songpan, and Jiuzhaigou County before reaching Lanzhou. The entire route rises from the Chengdu Plain, at an altitude of 500 m, to the eastern edge of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, at 3400 m. The Ping’an Tunnel is the most critical control project on this route, with a total length of 28,428 m, located in Mao County, Sichuan Province. The Ping’an Tunnel employs a double-hole scheme, with the left tube tunnel totaling 7550 m. Based on the Chinese rock mass grade system, this includes sections with II and III-grade surrounding rock, totaling 16,230 m, and sections with IV-grade surrounding rock, totaling 4648 m. The right tube tunnel has a total length of 7166 m, including sections with II and III grade surrounding rock, totaling 16,465 m, and sections with V grade surrounding rock, totaling 4797 m (The description of the Chinese rock mass grades is listed in Table 2). The geographic location and tunnel shape information are shown in Fig. 1.

Based on geological survey data, the maximum burial depth of the tunnel reaches 1720 m. The preliminary geological survey revealed that the surrounding rock mainly consists of sandstone and limestone. Mechanical experiments on rocks extracted from drilling indicated that the rock has a high compressive strength, with the maximum compressive strength measured at 127.7 MPa (It was obtained through uniaxial testing of rock samples obtained from hydraulic fracturing and geological drilling experiments). Simultaneously, based on the relationship between burial depth and geostress, it can be predicted that the in-situ stress value in some tunnel areas is high. The maximum principal stress of the tunnel is estimated to exceed 40 MPa (The extremely high ground stress value near the maximum burial depth of the tunnel). Considering the partial overlap between high-stress and hard rock areas, the stress conditions and rock properties required for rockburst disasters can be simultaneously met. Therefore, the risk of rockburst hazard during tunnel construction in certain sections is high.

Inversion analysis of the initial in-situ stress field of the Ping’an tunnel

In-situ stress test by hydraulic fracturing

The in-situ stress data were measured by two borehole hydraulic fracturing methods at the Ping’an tunnel mileage DK160 + 100 right 10 m (DZ-TP-9) and DK171 + 550 left 8 m (DZ-TP-10) to utilize in-situ stress field inversion technology and obtain the original rock in-situ stress field state of the Ping’an tunnel. These measurements are the basis for the in-situ stress inversion work. The depth of the two boreholes is approximately 781.0 m, the test hole diameter is 91.0 mm, and hydraulic fracturing stress measurement was conducted 6 times between 545.0 and 760.0 m of the borehole position. The in-situ stress results and measurement positions of the hydraulic fracturing method are shown in Table 3; Fig. 2. The stress σ2 generated by the self-weight of the rock mass is considered the intermediate principal stress.

From the data in Table 3, it can be observed that the maximum horizontal principal stress value of the in-situ stress measured in the in hydraulic fracturing experiments ranges from 15.30 to 21.13 MPa (σ1), the minimum horizontal principal stress (σ3) ranges between 10.13 and 13.95 MPa, and the vertical stress (σ2) ranges between 12.98 and 18.23 MPa. Based on the burial depth of the tunnel construction area, the maximum and minimum horizontal principal stress values at the borehole measurement point reach approximately 20 and 14 MPa, respectively. Overall, the three-way principal stress value of the tunnel follows the law of σ1 > σ2 > σ3, and the characteristics of the in-situ stress are primarily horizontal structural stress. The measured in-situ stress data show that the tectonic in-situ stress in this area is relatively high. Considering that the tunnel will pass through a significant number of hard rock strata, the risk of rockburst hazard during tunnel construction in the high-stress, high-stressed strong rock sections is high.

Inversion analysis of three-dimensional initial in-situ stress field of Ping’an tunnel

Many factors influence the in-situ stress field, such as fault, lithology, and bulk density, and the relationships between these factors are complex, making it difficult to quantitatively and accurately characterize them with mathematical formulas. There are currently numerous methods for stress inversion41,42,43,44,45,46. However, the multiple linear regression method identifies potential patterns from the complex distribution characteristics of the in-situ stress field, allowing for accurate reproduction of the macroscopic in-situ stress field of the tunnel. Given the complexity of the in-situ stress field, existing research indicates that the initial in-situ stress field results obtained through the multiple linear regression method are relatively reasonable and reliable, making the multiple linear regression inversion method the most widely used in in-situ stress inversion analysis46,47. Therefore, the multiple linear regression inversion method was utilized for the in-situ stress field of the Ping’an tunnel, and the process is as follows. Based on mountain elevation data from the selected range and using data coupling technology between CAD and Rhinoceros software, a corresponding three-dimensional model of the mountain of Ping’an Tunnel is established. Then, the 3D model is imported into numerical simulation software (Abaqus 2024), and boundary conditions are then applied to simulate the influence of various factors on the formation of the in-situ stress field, as outlined below:

-

(1)

Model establishment and parameter selection.

The total length of the Ping’an Tunnel is 28.428 km, with an axial model length of 28.428 km, a lateral width of 5000 m, 909,270 nodes, and 606,873 elements, as depicted in Fig. 3. The elastic constitutive model was used in the calculation, and the formation conditions were simplified to a certain extent. Due to the inability to accurately obtain the strength characteristics of all surrounding rocks along the tunnel axis direction, the values of rock mass mechanical parameters were comprehensively determined by geological exploration data and laboratory test results, as detailed in Table 4.

-

(2)

Determine the boundary conditions.

Based on previous research findings, self-weight and tectonic stress are the primary factors influencing the stress field of the original rock. Therefore, based on the previously established numerical model, multiple stress fields were applied to the model. The stress data from the corresponding measurement points under each stress field condition were extracted and used as the basis for multiple linear regression. Figure 4 illustrates the application of the boundary cases for the self-weight stress field and the tectonic stress field during the numerical calculation process. The specific application methods are as follows:

-

Self-weight stress field.

Based on the rock parameters in Table 4, gravity was applied along the Y direction in numerical simulation, and normal displacement constraints were applied to the side and bottom surfaces, as illustrated in Fig. 4a.

-

Tectonic stress field in the X and Y directions.

The X and Z distributions of the numerical model were subjected to a uniform load perpendicular to the surface, while normal displacement constraints were applied to the other sides and bottom surfaces, as shown in Fig. 4b and c.

-

XOZ shear stress field.

Based on the principles of elastic mechanics, in order to generate a pure shear stress field inside the rock mass, boundary displacements in the directions shown in Fig. 4d can be applied on the four sides of the model, and the displacement values applied by the short side and the long side are different. The ratio of boundary displacements applied by the short side to the long side equals the ratio of the long side to the short side at the bottom of the model48. Therefore, equivalent shear stress was simulated utilizing boundary displacements to the four sides of the model, with a displacement of 0.005 m on the X plane (front and back) and a displacement of 0.028428 m on the Y plane (left and right).

Based on the numerical analysis, the calculation results of the self-weight stress field in the Y direction, the uniform load boundary in the X direction, the uniform load boundary in the Z direction, and the XOZ plane displacement boundary of the Ping’an Tunnel were obtained, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

-

(3)

Regression inversion of the initial in-situ stress field.

The tunnel stress field is the result of the combined action of multiple influencing factors. Assuming that there are P variables that affect the distribution of the initial stress field, recorded as x1, x2, …, xp, then the quantitative relationship between the initial stress field and the variables x1, x2, …, xp can be classified as a multiple regression analysis problem. According to the multiple regression inversion method, the regression calculation value of the initial stress field is used as the dependent variable \({\widehat {\sigma }}_{k}\), and the stress value \({\sigma _{{k}}^{i}}\) calculated as a function of each influencing factor is used as the independent variable. The form of the regression equation is shown in Eq. (1)

where k is the observation point number, \({\widehat {\sigma }}_{k}\) is the regression calculation value of the kth observation point, Li is the multivariate retrospective coefficient of the corresponding independent variable, \({\sigma _{{k}}^{i}}\) is the single-column matrix of computed values for the corresponding stress components, and i is the number of operating conditions (i = 1, 2, …, n).

Based on the principle of multiple linear regression, there is a set of Li such that the residual value is minimized, resulting in a more accurate stress inversion when the residuals are smaller. The equation for solving this group of Li is indicated in Eq. (2). Since the coordinate system used in the numerical analysis differs from the system used in borehole measurements, based on the theory of elastic mechanics, it was necessary to convert the coordinates of the measured in-situ stress data to perform multivariate linear analysis, as shown in Eq. (3).

where \({\sigma _{ij}}\) and \({\widehat {\sigma }_{i^{\prime}j^{\prime}}}\) are the stress components in the old and new coordinate systems; \({a_{i^{\prime}i}}\) and \({a_{j^{\prime}j}}\) are the conversion factors.

After performing the coordinate transformation using Eq. (3), the regression coefficient Li was solved based on Eq. (2). A significance test was then conducted to analyze the accuracy of the regression. If the accuracy meets the required standards, the stress field data in Fig. 5 and the regression coefficient Li can be utilized to invert the original rock in-situ stress field for the entire tunnel site area.

After the coordinate transformation using Eq. (4), the initial in-situ stress field regression function for the Ping’an Tunnel engineering area is obtained based on the following equation:

where \({\sigma _{Ping{\prime }an}}\) is the stress field regression value; \({\sigma _X}\), \({\sigma _Y}\), \({\sigma _Z}\), and \({\sigma _{XOZ}}\) are the stress fields in Fig. 5, respectively.

After determining the in-situ stress field of the original rock using multiple linear regression, the in-situ stress data at the borehole (DZ-TP-10) measuring point were recalculated using the multiple linear regression equation to test its accuracy.

These results are listed in Table 5; Fig. 6. Table 5 shows that the relative error between the measured and regression values up to 12%, and the relative error between the DZ-TP-9 stress inversion data and the measured value from the undisplayed borehole DZ-TP-9 up to 13%. This indicates that the stress inversion was accurate and credible. The approximate mileage and specific locations of potential rockburst hazard can be predicted, and the level of rockburst hazard can be classified based on the inversion data and the criteria for rockburst hazard.

Rockburst hazard mileage prediction technology based on the stress intensity ratio

Prediction theory and outcomes

The rock burst prediction method based on the strength-stress ratio is one of the many methods for predicting rock burst disasters at a macro level. Although many advanced methods, such as neural networks and fuzzy mathematics, have emerged at the macro level for predicting rock burst disasters, they require many samples to ensure the accuracy of the prediction results. In addition, the quality of the samples significantly impacts the accuracy of the prediction results, making it impossible to raise and apply these methods. However, the rock burst disaster prediction method based on the strength-stress ratio considers the two most important factors, rock strength and geostress, that affect the occurrence of rock burst disasters. This prediction method is concise and highly accurate. Therefore, the rockburst prediction method based on the strength-stress ratio is widely used in predicting rockburst disasters, and its prediction results are widely recognized. Therefore, this method is selected for predicting rockburst hazard, and the selected rock strength-stress ratio criterion is shown in Eq. (5):

In addition, applying this method is difficult to obtain geostress data, so the stress inversion method is introduced in the macro prediction of rockburst disasters. Using this method can effectively make up for the defect. Based on the elastic mechanics formula, \({\sigma _{xx}}\) and \({\sigma _{yy}}\) at the tunnel axis position are obtained through stress inversion in the previous chapter, and the maximum principal stress \({\sigma _1}\) at a certain point was determined relying on the elastic mechanics Eq. (6).

The calculated maximum principal stress data along the tunnel axis are depicted in Fig. 7 (measuring points at 100 m intervals).

Figure 7 indicates that due to the significant fluctuation in the tunnel’s buried depth, the difference between the highest and lowest points is approximately 1700 m. This caused the principal stress of the tunnel to fluctuate considerably along the tunnel axis. The maximum value of the principal stress is located at 9300 m from the tunnel entrance, with a value of 45.5 MPa. The principal stress distribution along the tunnel axis indicated that because most of the tunnel construction area is deeply buried, the in-situ stress of the original rock was high during tunnel construction. Compared to the strength of the surrounding rock, the construction period is prone to frequent tunnel rockburst hazard.

Figure 8 depicts the rock strength-stress ratio at the tunnel axis position obtained by combining with the data in Table 4. It demonstrates that the strength-stress ratio of the rock is high near the entrance and exit of the tunnel, while the strength-stress ratio is low in the middle of the tunnel. This is due to the relatively shallow burial depth at the tunnel entrance and exit and the relatively deep burial in the middle section. The risk of rockburst occurrence is determined using Eq. (5), as shown in Fig. 9. The risk of rockburst in the tunnel is relatively high. The area without rockburst is 4000 m, accounting for 14.1%; the slight rockburst area is 4500 m, accounting for 15.8%; the moderate rockburst area is 7900 m, accounting for 27.8%; and the substantial rockburst area is 12,000 m, accounting for 42.3%. The combined moderate and strong rockburst sections are estimated to total 20 km, accounting for over 70.1% of the length, indicating an extremely high risk of rockburst hazard.

Analysis of the accuracy of tunnel rockburst hazard mileage prediction

The accuracy of the method described in this study was assessed by comparing it to the actual occurrence of rockburst hazard during tunnel construction to further validate the prediction results of tunnel rockburst hazard mileage based on the strength-stress ratio and stress inversion. Based on relevant research results and recommendations from on-site construction engineers, a rockburst intensity classification index using the observed dynamic rockburst phenomena was established, as listed in Table 6. During the construction of the Ping’an Tunnel, the rockburst hazard in the left and right tubes were recorded based on Table 6 and compared to the prediction results. The findings are listed in Tables 7 and 8. In the statistical process, because the impact of slight rockburst on tunnel construction was minimal and the phenomenon was less, only moderate and strong rockburst occurrences were primarily counted during the construction process.

Tables 7 and 8 indicate that 33 medium-scale and above rockburst hazard occurred during the construction of the Ping’an Tunnel. From the perspective of predicting the possibility of rockburst hazard, the actual locations of rockburst occurrences are within the prediction range. In terms of predicting the occurrence of rockburst hazard, 17 rockbursts occurred in the left tube, with the accuracy of the rockburst hazard level being correct 12 times, resulting in a prediction accuracy of 70.6%. Similarly, 16 rockbursts occurred in the right tube, with 11 accurate predictions, giving a prediction accuracy of 68.7%. The accuracy of the prediction of rockburst hazard levels proposed in this study is about 70%, reaching a high level of credibility. This method is considered to provide a valuable reference for predicting rockburst hazard. In addition, the total mileage of rockburst hazard in the Ping’an Tunnel reaches 3923 m, of which the mileage in the left tube of the tunnel is 1820 m, and in the right tube, it is 2103 m. Therefore, the rockburst hazard can be predicted in advance, and the location and intensity of the rockburst hazard can be clarified. This enables targeted measures to be taken during the design stage, minimizing the impact of rockburst hazard on tunnel construction.

Prediction of rockburst hazard location of tunnel structure based on energy theory

Rockburst energy prediction theory and laboratory experiments

The mileage and intensity of rockburst hazard are accurately predicted using the research methods proposed above. However, the occurrence of rockburst energy in the tunnel structure and surrounding rock is difficult to detect, making it challenging to predict the detailed location of rockburst hazard during construction. This issue significantly interferes with efficient and economic prevention and control of rockburst hazard.

Based on the law of conservation of energy, when a rock is subjected to external forces, the work done by the external forces will be converted into the energy acts on rocks. When the external force is small, all the work done by the external force is converted into the elastic strain energy of the rock, i.e., the rock only undergoes elastic deformation without failure. When the external force is large, and the energy input into the rock exceeds the maximum elastic strain energy that can be stored, the rock will transition from an elastic state to a plastic failure state. The same applies to rockburst hazard, only when the energy input inside the rock exceeds its ultimate strain energy, will the rockburst hazard occur. This is the theoretical basis for the energy criterion.

From an energy perspective, the sudden unloading of rock confining pressure releases a large amount of energy accumulated in the rock, which causes a rockburst hazard. The energy of rockburst hazard primarily originates from two sources. The first source of energy comes from the rock before it is exposed. Before excavation affects it, the rock within a specific depth range on the tunnel surface experiences high-ground stress, forming substantial confining pressure. With tunnel excavation, the rock surrounding a certain tunnel area undergoes stress redistribution and transfer, causing an increase in the maximum principal stress. Under these pressures, the rock is compressed, generating internal strain energy. The second energy source arises from the exposure of energy storage rock due to excavation. When the stress on the exposed rock surface quickly drops to zero (in the experiment, this is considered as the confining pressure of the specimen dropping to zero), stress in other directions remains (in the experiment, axial compression is still present). Significant deformation occurs under the influence of stress in other directions and the accumulated strain energy within the rock, potentially leading to destruction and ejection, which constitutes the process of rockburst. The direction of the exposed rock surface is generally perpendicular to the maximum principal stress, and during the unloading process, the maximum principal stress continues to act on the rock, contributing to the second source of strain energy responsible for rockburst hazard.

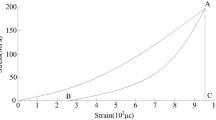

A rockburst energy criterion was proposed based on the energy sources during rockburst hazard, derived from rapid unloading experiments of confining pressure. This experiment was conducted using three-axis experimental equipment, as depicted in Fig. 10. The early stage of the experiment is consistent with the conventional three-axis experiment. After installing the specimen, confining pressure is applied. The key feature of the experiment is the stage following the application of confining pressure, as depicted in Fig. 11. After confining pressure loading is complete, stage 1 involves loading axial pressure to 80% of the peak compressive strength (A triaxial compression test should be conducted prior to the unloading confining pressure experiment, and the peak compressive strength should be measured through a triaxial test under the same confining pressure conditions). This step aims to simulate the stress concentration phenomenon caused by excavation disturbance during a rockburst. The purpose of loading axial pressure to 80% of the failure pressure is to simulate the ultimate stress state of the rock as much as possible before the occurrence of a rockburst hazard. The 20% reduction in axial pressure is to avoid specimen failure from excessive axial pressure loading. Stage 2 is the pressure maintenance phase, which simulates the energy storage and deformation of the surrounding rock under confining pressure and concentrated stress. Stage 3 is the unloading stage of confining pressure, where the confining pressure of the specimen is rapidly reduced to zero within 1–2 s. At this point, the specimen experiences significant radial expansion and axial compression, with the axial load still applying energy to the surrounding rock. This stage simulates the rapid unloading of rock-confining pressure caused by excavation. Stages 1–3 represent energy input phases, while stage 4 is the energy output phase. Therefore, the energy required for rockburst hazard triggered by sudden stress changes is the sum of the first three stages. When the accumulated energy in the surrounding rock exceeds the total energy input, the probability of a tunnel rockburst hazard is high.

Then, a rock mechanics experiment is conducted using rock samples taken from the position of D8K163 + 495 on the left tube of Ping’an Tunnel. The burial depth is relatively large, and based on the stress inversion results, the confining pressure of the rocks in this area is approximately 30 MPa. Two sets of experiments are then conducted. First, a conventional triaxial experiment is performed to determine the ultimate compressive strength of the rock under the confining pressure of 30 MPa. The experimental results are presented in Fig. 12, showing that the peak compressive strength is around 254 MPa. Then, the confining pressure load-unloading experiment described in this study is conducted, and the results are depicted in Fig. 13.

The calculation method for the energy storage limit is derived from the approach proposed in the study, yielding an energy storage limit of 0.8105 MJ/m3 for the rock. Based on the research results from the literature 49,50,51 the evaluation index Umix for rockburst induced by transient unloading is classified to represent the intensity of rockburst in the actual project.

where U is the actual stored energy of the rock mass, which can be obtained by finite element numerical calculation and tracking the change in elastic strain energy in each element; Ulim is the energy storage limit of the surrounding rock induced by transient unloading in the unconfined pressure test, which was measured to be 0.8105 MJ/m³ based on the experiment.

Numerical model for predicting the energy of surrounding rock in rockburst tunnels

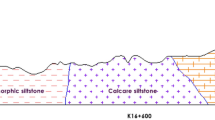

Based on the actual construction of the Ping’an Tunnel, a numerical simulation model was established, as shown in Fig. 14. Considering the relatively stable mechanical properties of the surrounding rock and support material (Sprayed concrete) within a small range, and the surrounding rock and support material was simplified to homogeneous material in the numerical software Abaqus 2024, the rock and soil mass and support material model adopts an elastic ideal plastic model considering the Mohr-Coulomb yield criterion. The size of the 3D calculation model was 200 × 60 × 200 m, and the surrounding rock in the model was simulated using hexahedral elements. The numerical calculation model was divided into 74,620 elements, as shown in Fig. 14. Based on the rock samples collected on-site and the results of indoor experiments, the calculation parameters of the model in the numerical simulation are detailed in Table 9. The stress situation of a typical rockburst tunnel section (YD8K168 + 050) was selected. Based on the stress inversion results, the corresponding confining pressure was applied to the boundary surface to simulate the in-situ stress field. The Ping’an Tunnel was constructed using the double-hole method, where the left tube was excavated first. The tunnel adopted full-section excavation, with an excavation footage of 2 m. The distance between the left and right holes was 30 m, and the left tube was 60 m ahead of the right tube, consistent with the construction method at the site. After the tunnel excavation was completed, the energy change in the surrounding rock is depicted in Fig. 15. The energy shown in Fig. 15 is strain energy, and numerical simulation software can calculate the strain energy U of each element based on its stress state and mechanical parameters. The calculation formula is shown in Eq. (8).

During the calculation process, energy monitoring points were set up at different locations in the tunnel to quantify the relative risk of rockburst hazard in various parts of the tunnel and facilitate analysis. The energy density of each part during the tunnel excavation is illustrated in Fig. 16.

Figure 16 indicates that the energy at the tunnel face is the most concentrated, primarily at the arch waist and side wall. The maximum value at the side wall is 0.3906 MJ/m3, while the maximum value at the arch waist is 0.3857 MJ/m3. The energy of a rock mass in the middle of the tunnel face initially increases, then gradually decreases and eventually stabilizes. The maximum energy density at the tunnel face is 6 m away from the excavation face, with a value of 0.2885 MJ/m2. The energy of the vault section reaches a maximum of 0.2051 MJ/m3 before decreasing. These data indicate that the possibility of rockburst is highest at the side wall and arch waist during excavation. Due to the considerable compressive stress during excavation, the continuous input of energy at the side wall is the primary cause of the rockburst. The placement of stress relief holes at these locations during excavation facilitates the early release of energy from the tunnel face, reducing the likelihood of a rockburst. In addition, after the occurrence of rockburst accidents, it is recommended to immediately use sprayed concrete to provide specific support to the rock mass to reduce the probability of a second rockburst disaster occurring at that location. The rockburst hazard level can be predicted based on the rockburst hazard prediction criteria revealed in Fig. 16 and Eq. (8). The rockburst hazard that occurred in the tunnel is shown in Fig. 17.

Table 10 Lists the actual situation and prediction results of the rockburst hazard at the tunnel site. It indicates that the rockburst prediction method discussed in this study is generally consistent with the occurrence of rockburst hazard in the field, demonstrating the accuracy and effectiveness of the prediction method.

Conclusions and discussion

The maximum principal stress distribution characteristics along the tunnel axis are determined through stress inversion based on the in-situ stress data obtained from the hydraulic fracturing of the Ping’an Tunnel of Chenglan Railway. The location and grade of rockburst hazard are predicted using the strength-stress ratio and energy criterion. In addition, the accuracy is assessed by comparing it with the rockburst hazard observed at the engineering site. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

The stress inversion method can relatively accurately obtain the initial stress field of deep-buried high-ground stress tunnels. The discrepancy between stress inversion and borehole measurement data is generally within 13% in this study, which means that stress inversion can be utilized to obtain the initial stress field data of the tunnel and apply it to subsequent research.

-

(2)

The prediction results of rock burst level based on the combination of geostress field and strength stress ratio indicate that the risk of rockburst hazard in the tunnels is relatively high. The moderate rockburst area is 7900 m, accounting for 27.8%, while the strong rockburst area is 12,000 m, accounting for 42.3%. The moderate and strong rockburst sections are expected to cover 20 km, representing more than 70.1% of the total length, indicating an extremely high risk of rockburst hazard and a significant impact on tunnel construction.

-

(3)

The on-site recording of rockburst disasters confirms the effectiveness of the prediction method proposed in this study for rockburst disasters from the macro perspective. On the one hand, the actual occurrences of rockburst hazard all fall within the predicted range. On the other hand, the overall accuracy of the rockburst hazard prediction proposed in this study is approximately 70%, reflecting a high confidence level. The predicted results can further optimize the design and construction support of rockburst-prone tunnels and play a crucial role in preventing and controlling tunnel rockburst hazards.

-

(4)

From a microscopic perspective, based on the characteristics of rock burst disasters caused by instantaneous unloading and energy sources, a rockburst energy criterion is proposed, derived from rapid unloading experiments of confining pressure. The location of rock burst disasters in tunnel structures is predicted through indoor experiments, numerical simulations, and energy criteria. The location of the on-site rock burst disaster is entirely consistent with the predicted results, further validating the accuracy of this method.

-

(5)

Based on stress inversion, indoor experiments, and energy criteria, this study predicts rockburst disasters from both macro and micro perspectives. It has significant guiding significance for the design and construction of rockburst tunnels. However, due to limitations in computing power, the stress inversion model established in the study is simplified to a certain extent. In the future, the stress model can still be refined when established to obtain more accurate and detailed geostress field data. The new method proposed in the study for predicting the location of rockburst disasters from an energy perspective still needs to be validated with more case data to confirm its feasibility and facilitate its promotion and application.

Data availability

The curve data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

He, M., Cheng, T., Qiao, Y. & Li, H. A review of rockburst: experiments, theories, and simulations. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 5, 1312–1253 (2023).

Zhou, J., Zhang, Y., Li, C., He, H. & Li, X. Rockburst prediction and prevention in underground space excavation. Underground Space. 14, 70–98 (2024).

Hu, J. et al. Rockburst hazard control using the excavation compensation method (ECM): a case study in the Qinling water conveyance tunnel. Engineering. 34, 154–163 (2024).

Wu, A., Sun, Y., Sen, G., Shen, H. & Yang, B. Characteristics of rockburst and its mining technology in mines. J. Central S. Uni. Technol. 9, 255–259 (2002).

Liu, X. et al. A new rockburst criterion of stress-strength ratio considering stress distribution of surrounding rock. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82, 1 (2023).

Russenes, B. Analysis of Rock Spalling for Tunnels in Steep Valley Sides (Norwegian Institute of Technology, Trondheim, 1974).

Barton, N., Lien, R. & Lunde, J. Engineering classification of rock masses for the design of tunnel support. Rock Mech. 6, 189–236 (1974).

Hoek, E. & Brown, E. Underground Excavation in Rock (The Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, London, 1980).

Małkowski, P. & Niedbalski, Z. A comprehensive geomechanical method for the assessment of rockburst hazards in underground mining. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 30, 345–355 (2020).

Wang, Y., Li, W., Li, Q., Xu, Y. & Tan, G. Comprehensive evaluation method of fuzzy mathematics for rock burst prediction. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 17, 493–501 (1998).

Kidybiński, A. Bursting liability indices of coal. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 18, 295–304 (1981).

Zhang, Z., Gao, F. & Shang, X. Rock burst proneness prediction by acoustic emission test during rock deformation. J. Central South Univ. 21, 373–380 (2014).

Goodman, R. Introduction to Rock Mechanics (John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1980).

Chen, G., Zhang, J., Tang, W., Li, T. & Zhang, G. A new criterion of rock burst proneness based on residual energy release rate index. J. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 16, 5004–5026 (2024).

Li, P. et al. Research progress of rockburst prediction and early warning in hard rock underground engineering. J. China Coal Soc. 44, 447–465 (2019).

Qiao, L., Dong, J., Liu, J. & Chen, L. Review on the study progress of rockburst mechanism and prediction in underground metal mines in China. Metal Min. 2023, 14–28 (2023).

Basnet, P., Mahtab, S. & Jin, A. A comprehensive review of intelligent machine learning based predicting methods in long-term and short-term rock burst prediction. Tunnel. Underground Space Technol. 142, (2023).

Wiles, T. Correlation Between Local Energy Release Density Observed Bursting Conditions at Creighton Mine (Mines Research, Sudbury, Canada, 1998).

Cook, N., Hoek, E., Pretoriu, J., Ortlepp, W. & Salamon, M. Rock mechanics applied to study of rockbursts. 66, 435–528 (1966).

Zhou, J., Zhang, Y., Li, C., He, H. & Li, X. Rockburst prediction and prevention in underground space excavation. Underground Space. 14, 70–98 (2024).

Su, S., Gao, T., Zhu, Y., Fang, X. & Fan, T. Rockburst Prediction via Multiscale Graph Convolutional Neural Network. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 1–19 (2024).

Zhang, J. Exploration on coal mining-induced rockburst prediction using Internet of things and deep neural network. J. Supercomput. 78, 13988–14008 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Rockburst prediction based on the KPCA-APSO-SVM model and its engineering application. Shock Vibr. 2021, 7968730 (2021).

Yin, X. et al. Strength of stacking technique of ensemble learning in rockburst prediction with imbalanced data: comparison of eight single and ensemble models. Nat. Resour. Res. 30, 1795–1815 (2021).

Wang, P., Wei, Q., Wang, J. & Zhao, G. Risk assessment of railway tunnel construction based on grey fuzzy linguistic theory. J. Railway Eng. Soc. 39, 106–112 (2023).

Yin, X. et al. Intelligent early warning for underground engineering rockburst disaster: an improved multi-attribute group decision-making model based on fuzzy theory. J. Basic Sci. Eng. 30, 374–395 (2022).

Liu, R., Ye, Y., Hu, N., Chen, H. & Wang, X. Classified prediction model of rockburst using rough sets-normal cloud. Neural Comput. Appl. 31, 8185–8193 (2019).

Long, G. et al. Probability prediction method for rockburst intensity based on rough set and multidimensional cloud model uncertainty reasoning. Environ. Earth Sci. 83, 1–21 (2024).

Feng, G. et al. Microseismic characteristics of rockburst development in deep TBM tunnels with alternating soft-hard strata and application to rockburst warning: a case study of the Neelum-Jhelum hydropower project. Tunnel. Underground Space Technol. 122, (2022).

Liu, F., Tang, C., Zhang, Y. & Ma, T. Rockburst and microseismicity characteristics in the Qinling water conveyance tunnel of the Hanjiang-to-Weihe River Diversion Project. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 148, (2021).

Yu, Y. et al. Time fractal behavior of microseismic events for different intensities of immediate rock bursts. Int. J. Geomech. 18, 6018016 (2018).

He, B., Wang, B., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Jin, Z. A review of rockburst: insights from engineering sites to theoretical investigations. J. Central South Univ. 31, 2607–2643 (2024).

Singh, S. The influence of rock properties on the occurrence and control of rockbursts. Min. Sci. Technol. 5, 11–18 (1987).

Tan, Y. Discussion on energy impact index of rock bursting rock. Hydrogeol. Eng. 19, 10–12 (1992).

Wang, J. & Park, H. Comprehensive prediction of rockburst based on analysis of strain energy in rocks. Tunnel. Underground Space Technol. 16, 49–57 (2001).

Tajdus, A., Cieslik, J. & Tajdus, K. Rockburst hazard assessment in bedded rock mass: laboratory tests of rock samples and numerical calculations. Arch. Min. Sci. 59, 591–608 (2014).

Gong, F., Yan, J. & Li, X. A new criterion of rock burst proneness based on the linear energy storage law and the residual elastic energy index. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 37, 1993–2014 (2018).

Gong, F., Yan, J., Li, X. & Luo, S. A peak-strength strain energy storage index for rock burst proneness of rock materials. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 117, 76–89 (2019).

Zhu, F., Pan, C. & Guo, R. New rock burst index effective impact-energy index. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 19, 83–84 (2002).

Tang, L., Pan, C. & Wang, W. Surplus energy index for analysing rock burst proneness. J. Central South Univ. Sci. Technol. 33, 129–132 (2002).

Feng, X. et al. Monitoring, warning, and control of rockburst in deep metal mines. Engineering. 3, 538–545 (2017).

Wang, C., Gao, G., Yang, S., Yao, R. & Huang, L. State Analysis and Estimation of In-situ Stress along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway Based on Tectonic Stress Zoning in Western China. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 38, 2242–2253 (2019).

Jiang, Q., Feng, X., Chen, J., Zhang, C. & Huang, S. Nonlinear inversion of three-dimensional in-situ stress field in Jinping II hydropower station site. Rock Soil Mech. 29, 3003–3010 (2008).

Meng, W. et al. Two-stage back analysis of initial geostress field in rockburst area based on lateral pressure coefficient. Rock Soil Mech. 39, 4191–4200 (2018).

Tang, H., Li, T., Meng, L., Wang, D. & Wang, M. In-situ stress field inversion analysis of Erlangshan deep buried tunnel of Sichuan-Tibet Railway. Railway Eng. 55, 65–69 (2015).

Shi, C., Wang, J., Chen, C., Wang, H. & Hu, W. Application of multiple linear regression method in in-situ stress field inversion of a tunnel. Yangtze River 46, 47–50+64 (2015).

Wang, Q., Ju, N., Huang, J., Du, L. & Zhang, C. Inversion analysis of initial in-situ stress field of Sangzhuling extra-long tunnel. Sci. Technol. Eng. 16, 137–143 (2016).

Fei, W. et al. Inversion of initial in-situ stress field of underground plant of Fengning pumped storage power station. Yangtze River 51, 112–116 (2020).

Zhang, Q., Zhong, Z. & Gong, B. Application of boundary displacement to generate pure shear stress and back analysis. J. Changjiang River Sci. Res. 17, 34–36 (2000).

Chen, W., Lv, S., Guo, X. & Qiao, C. Research on unloading confining pressure tests and rockburst criterion based on energy theory. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 28, 1530–1540 (2009).

Zhang, J. & Fu, B. Rockburst and its criteria and control. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 27, 2034–2042 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52378414).

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52378414).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by H.L., manuscript review and editing were performed by Y.Y., L.T. and Z.Z. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Yang, Y., Zhang, Z. et al. Prediction and classification technology of rockburst hazard in deep buried and high in-situ stress tunnel. Sci Rep 15, 9633 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93351-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93351-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effect of Anchor Plate on Prestressed Anchor Cable Performance in Soft Rock Tunnels

Geotechnical and Geological Engineering (2025)