Abstract

Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry (PRISm) is a specific subtype of pre-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (pre-COPD). People with PRISm are at risk of progression to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). We developed a model to predict progression in subjects with PRISm. We screened 188 patients whose lung function transitioned from PRISm to COPD and 173 patients with PRISm who remained stable over two years. After excluding 78 patients due to incomplete clinical or laboratory data, a total of 283 patients were included in the final analysis. These patients were randomly divided into a training cohort (227 patients) and a validation cohort (56 patients) at a 8:2 ratio. LASSO regression and multivariate logistic regression were used to identify factors influencing progression. Among the 283 patients, 134 progressed to COPD. The model developed using six variables showed good performance, with areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of 0.87 in the training cohort and 0.79 in the validation cohort. The model demonstrated excellent calibration and was clinically meaningful, as shown by decision curve analysis (DCA) and clinical impact curve (CIC). We developed China’s first prediction model for the progression of lung function from PRISm to COPD in a real-world population. This model is conducive to early identification of high-risk groups of pulmonary function deterioration, so as to provide timely intervention and delay the occurrence and progression of the disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is no doubt that COPD has become one of the major global public problems due to its high morbidity and mortality. It is characterized by persistent (often progressive) airflow limitation and chronic respiratory symptoms caused by airway abnormalities (bronchitis, bronchiolitis) and/or alveolar abnormalities (emphysema) and deserves the attention of people worldwide1,2. COPD is thought to be caused by tobacco smoking, however, in recent years studies have shown that COPD may be caused by impaired lung development3,4.Advancing insights into COPD mechanisms may reveal new strategies for disease prevention and progression control.

Unlike COPD, PRISm is considered to be a non-obstructive pulmonary dysfunction with reduced FEV1and FVC symmetry5,6. PRISm can be categorized into two groups based on the presence or absence of restrictive ventilatory abnormalities (FEV₁/FVC ≥ 0.7 and FVC %pred < 80%): restrictive PRISm and non-restrictive PRISm7,8. Measuring Total Lung Capacity (TLC) helps to more accurately assess the type and severity of pulmonary dysfunction. When TLC is reduced with an FEV₁/FVC ratio ≥ 0.7 and FEV₁ < 80%, it strongly supports the diagnosis of restrictive PRISm. Conversely, if TLC is normal, non-restrictive PRISm may be considered, along with other clinical indicators. Previous studies have shown that non-restrictive PRISm is associated with an increased risk of developing airflow obstruction within 5 years9. Since the term “Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry” was introduced by Wan et al. in 20145, it has been widely cited by researchers, and many large cohort studies have also adopted the criteria of FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.7 and FEV1< 80% predicted for defining PRISm10,11,12.Therefore, in our study, we adopted this definition as well. Recent evidence highlights a high prevalence of undiagnosed COPD, and even when COPD cannot be confirmed by PFT, this population shows signs of declining lung function, with PRISm being one of the subtypes at risk for disease progression and delayed treatment13.Moreover, PRISm is considered as a subtype that owns higher risk of progression to COPD14. A study by Kanetake et al. found that PRISm was an independent risk factor for the development of COPD in the Japanese population (OR 3.75, p< 0.001)15. The Rotterdam and COPD Gene study found that the incidence of transition from PRISm to COPD was significantly higher than in the group with normal lung function12,14.

Previous studies have shown that PRISm is a highly heterogeneous and unstable population characterized by a longitudinal transition to different categories of lung function (reverting to normal lung capacity, development of COPD, persistence of PRISm)10,12,14,16,17. Di He et al. used the English Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSA) cohort, which reported that patients with severe PRISm (both FEV1 and FVC < 80% predicted values, FEV1/FVC ≥ 70%) had increased respiratory symptoms, a higher risk of death, and a greater chance of progressing to COPD than those with mild PRISm (FEV1 < 80% predicted, FEV1/FVC ≥ 70%)17. Park et al.’s research identified that PRISm patients are at risk of developing COPD and should be carefully monitored regardless of lung function, with particular attention to older patients as well as those with wheezing symptoms18. Similar results have been reported in other studies that PRISm subjects have higher mortality and many different lung function trajectories10,17.Therefore, some aspects of PRISm are associated with the deterioration of lung function and development of COPD. However, the incidence of COPD in PRISm patients has been rarely reported. The population-based studies were limited on risk factors for PRISm progression.

It is well known that once pulmonary function deteriorates to COPD, reversal becomes challenging19. Therefore, early identification of PRISm patients who are susceptible to progression to COPD is extremely important. We analyzed clinical features of inpatients progressing from PRISm to COPD, identified progression risk factors, and developed predictive models for early intervention to prevent irreversible lung function decline.

Methods

Study design and population

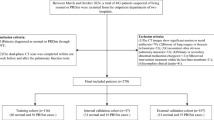

We extracted electronic medical records of 14,534 hospitalized patients who underwent at least two lung function tests at West China Hospital of Sichuan University between January 2012 and July 2020. After excluding 829 patients with incomplete baseline data, 8,561 with normal lung function, and 4,536 with stable COPD, we included 608 eligible patients (435 with COPD/PRISm and 173 with persistent PRISm) in the final analysis. Subsequent screening excluded 247 patients exhibiting unstable pulmonary function (defined as transitions between COPD, normal, or PRISm status during follow-up). 78 patients lacking complete clinical information and laboratory test results were further excluded. The final analysis included 283 patients: 134 showing disease progression and 149 without progression. The original study initially included 283 patients who were randomly divided into a training cohort (N = 227) and a validation cohort (N = 56) in an 8:2 ratio. The exclusion criteria for this study are listed as follows: (a) participants who had only one lung function test and had incomplete or inaccurate baseline clinical information; (b) participants whose lung function were normal and continued unchanged ; (c) patients diagnosed with COPD at baseline and continued unchanged; (d) Patients with unstable pulmonary function, defined as transitions between COPD, normal, or PRISm status during follow-up, including those whose lung function transitioned from COPD to PRISm or normal; (e) participants with incomplete clinical information or lacking detailed laboratory results; The flow chart illustrating the study participants is presented in Fig. 1. We used their data to establish retrospective cohorts and conduct analyses to explore risk factors for PRISm progression. In this study, 35 baseline variables were included in the prediction model as screening variables, and after further screening, the 6 most meaningful variables were eventually used to build the prediction model.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital on October 23, 2023.The ethical approval number for this study is Trial in 2023 (No. 1856). As this study was retrospective and all data were used for anonymous analysis, West China Hospital waived the requirement of informed consent.

Diagnosis of COPD and PRISm

Spirometer parameters, including FVC, FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio were measured by spirometer (Vmax229D, SensorMedics, CA, USA) measurement, as recommended by the American Thoracic Society20.

PRISm refers to non-obstructive pulmonary dysfunction with reduced FEV1 and FVC symmetry, defined as FEV1/FVC ≥ 70% and FEV1< 80% pred by pulmonary function test (PFT)6.

A fixed ratio of FEV1/FVC less than 70% is the standard for airflow restricted spirometry. This standard is simple and independent of reference values and has been used in many clinical trials to diagnose COPD21.

In our study, the diagnosis of COPD was not solely reliant on pre-bronchodilator spirometry (FEV1/FVC < 70%) but was established through a multi-dimensional clinical evaluation by experienced physicians. This included detailed clinical history (chronic dyspnea, cough, smoking/environmental exposures), chest CT findings (emphysema, bronchial wall thickening, or air trapping), and rigorous exclusion of asthma based on the absence of episodic wheezing, atopy, or symptom reversibility, alongside persistent airflow limitation despite inhaled corticosteroid therapy.

Data collection and processing

We gathered baseline data on various symptoms such as cough and dyspnea, demographic factors like sex, age, body mass index, and ethnicity, as well as information on smoking history, family history of respiratory illness, and comorbidities such as respiratory complications, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular issues, psychiatric disorders, chronic renal problems, and funnel chest. Additionally, we obtained lung function indicators including forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1, %pred), the ratio of forced expiratory volume in the first second to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC), and forced vital capacity (FVC, %pred). Furthermore, we collected initial laboratory test results upon admission, encompassing routine blood tests, blood biochemistry, and fibrinogen levels, to explore potential associations with lung function progression. The analysis also incorporated several commonly used ratio measures in clinical practice, including monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet lymphocyte ratio (PLR). All clinical data, including spirometry measurements, were collected during stable disease phases. Patients with acute exacerbations of COPD or worsening comorbidities during the observation period were excluded to minimize the influence of acute inflammatory responses on the analysis. Subsequent data underwent rigorous quality control and processing procedures.

Statistical analysis

We randomly divided participants into a training cohort and a validation cohort in an 8:2 ratio according to a simple randomization procedure. Continuous variables with normal distributions are represented by means and standard deviations, and skewered distributions are represented by medians and interquartile Range (IQR). For Categorical variables are presented in terms of frequency or percentage. Student’s t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum are used for continuous variables and chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables.

We first screened out variables with P values less than 0.05 based on lasso regression analysis, then performed multivariable logistic regression to determine the risk factors for PRISm progression, and finally used these factors to build a prediction model, which was presented in the form of a nomogram. When two-tailed p < 0.05, the results were considered significant. Where appropriate, results were expressed in terms of odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical analyses were performed using software R 4.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).We performed data extraction and analysis using several R packages, including “glmnet”, “metrics”, “rms”, “broom”, “pROC”, “rmda”. After building the model, we draw calibration curves to assess its calibration, employ ROC curves to evaluate its performance, and calculate the area under the curve (AUC, also known as C-statistics). Additionally, Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) and Clinical Impact Curve (CIC) were utilized to evaluate its clinical application value.

Establishment of a nomogram

We constructed a nomogram based on meaningful risk factors selected by lssso regression and multivariable logistic regression. Set different score values according to the different OR values of each factor. Next, based on the score value for each factor, use the corresponding position on the horizontal axis to determine the score for that factor. The scores for each factor are then combined to calculate an overall score, providing a specific probability of PRISm progress.

Results

Baseline demographics of the study participants

Following rigorous inclusion and exclusion criteria, our final analysis comprised 283 patients, including 134 with disease progression and 149 without progression. The baseline demographic characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 shows the clinical and demographic characteristics of patients in the two cohorts. Compared to the progression-free group, patients in the progression group exhibited older age, higher BMI, a higher prevalence of former and current smokers, lower predicted FEV1, lower FEV1/FVC ratio, lower predicted VC, a higher incidence of family history of respiratory disease, respiratory complications, chronic kidney disease, and a higher frequency of CT signs of emphysema. Laboratory tests also revealed significant differences in albumin, glucose, triglycerides, cholesterol, and fibrinogen levels between the two groups. In addition, during the data collection process, we found that the progression-free group showed a higher rate of funnel chest. (P < 0.05, Table 1). It is important to note that the progression-free group included many patients diagnosed with funnel chest, a condition predominantly found in adolescents according to previous studies. Hence, their clinical data may not adequately represent the condition of primarily stable PRISm patients. It is essential to include more representative populations in future studies.

In our comparative analysis of baseline data from the training cohort (N = 227) and validation cohort (N = 56), we observed no statistically significant differences in baseline demography and laboratory tests. Therefore, it is reasonable to use these cohorts as training and validation cohort for the model (Supplementary Table 1).

Feature selection

We utilized a LASSO regression algorithm to conduct feature selection in the training cohort, considering each feature individually. Lasso regression can effectively address the issue of multicollinearity that may arise during modeling. Among all 35 associated characteristic variables, 8 potential predictors were selected. In the LASSO analysis, eight variables with nonzero coefficients were retained (Fig. 2A).The most suitable tuning parameter λ for LASSO regression was determined to be 0.025, corresponding to the minimum value of the partial likelihood binomial deviance (Fig. 2B).

Feature selection by LASSO binary logistic regression model. A LASSO coefficient profiles for clinical features, each coefficient profile plot is produced vs. log (λ) sequence. Eight variables with nonzero coefficients were retained. B Selection of tuning parameter (λ) in the LASSO regression using 10-fold cross-validation via minimum criteria.

Multivariate analyses of risk predictors of lung function progression and create the prediction nomogram model using the training cohort

The eight retained variables were used for multivariable logistic regression analysis. The results of the multivariable logistic analysis for the progression of PRISm in the training cohort are presented in Table 2, and the odds ratios (ORs) for each risk factor, along with a 95% confidence interval, are illustrated using a forest plot (Supplementary Fig. 1). It is evident from the analysis that advanced age (P = 0.024), dyspnea (P = 0.046), comorbidity with respiratory disease (P = 0.005), and higher red blood cell count (P < 0.001) are positively associated with lung function progression. Conversely, patients with higher predicted FEV1 (P = 0.032) and FEV1/FVC ratio (P < 0.001) are at a lower risk of experiencing lung function progression. The nomogram was developed using six variable point scales, each corresponding to a respective variable. The total points were calculated as the sum of the points from these six variables. Finally, we set up a simple nomogram based on the selected risk factors (Fig. 3).

Apparent performance of nomograms to predict PRISm progression

The estimated progress of the nomogram model to predict the progression of PRISm in the training cohort has a good correlation with the actual progress. Our results show that the calibration curve almost coincides with the Y = X line, indicating that the model is well calibrated (Fig. 4).

To assess the accuracy of our model, we performed ROC analyses on patients. The AUCs for discriminating between patients with and without lung function progression were 0.869, and 0.792 in our training and validation cohorts, respectively (Fig. 5). The model’s classification performance was evaluated by assessing its sensitivity and specificity. In the training cohort, the sensitivity of the model was 0.835, while in the validation cohort, it was 0.960. The specificity of the model was 0.771 and 0.613 in the two cohorts, respectively. In addition, DCA results show that nomogram models have good clinical application value. The gray curve shows that all patients received the intervention, the black line shows that no patients received the intervention, and the red curve shows the clinical benefit of our model (Supplementary Fig. 2). CIC showed that the “high risk number” line was relatively close to the “high risk number with event” line, indicating that using this nomogram model to predict PRISm progression has a large clinical net benefit (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Discussion

Considering the high heterogeneity within the PRISm population, characterized by various progression or change trajectories, predicting the lung function progression of patients based on their actual changes has become an urgent issue14. In this study, we developed and validated a personalized predictive nomogram to assess the risk of PRISm progression to COPD, using cost-effective and readily available variables to help clinicians identify patients at higher risk of progression from PRISm to COPD for early intervention to delay irreversible lung function progression. The model demonstrates favorable predictive performance, as evidenced by reliable AUC values. Internal validation and evaluation further confirmed the nomogram’s accuracy in risk prediction.

In defining PRISm, we acknowledge the ongoing variability in diagnostic criteria across studies. While some authors classify PRISm as a condition where FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.7 and FVC < 80% of predicted values22,23,24, others include cases where either FEV1or FVC is below 80% of predicted values17. Notably, many large cohort studies have predominantly adopted the definition of FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.7 and FEV1< 80% of predicted values11,12,25. In our study, we aligned with this widely accepted criterion to ensure consistency and comparability with previous research. However, we recognize that the inclusion of cases with FVC < 80% may provide additional insights into the heterogeneity of PRISm. Future studies should explore the clinical and prognostic implications of differing definitions to establish a more standardized diagnostic framework. Additionally, integrating other functional metrics, such as total lung capacity (TLC) and diffusing capacity (DLCO), may further refine the classification and improve our understanding of PRISm’s underlying mechanisms. In recent years, significant changes have occurred in the interpretation of PFTs. The European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) now recommend using the lower limit of normal (LLN) and Z-scores to define pulmonary abnormalities26,27. These updated criteria improve diagnostic accuracy and reduce misclassification caused by fixed thresholds. In our study, although some analyses still relied on the traditional FEV1/FVC ≥ 70% fixed ratio, we recognize the importance of LLN and Z-scores. Specifically, LLN allows for more precise identification of individuals with preserved FEV1/FVC ratios but impaired lung function, which is particularly relevant in defining PRISm. This approach enhances diagnostic accuracy and provides clearer guidance for early intervention28. Moving forward, we plan to adopt LLN and Z-scores to better classify PRISm patients. We also recommend integrating these updated criteria into clinical practice to improve the diagnostic value of PFTs.

Previous studies have shown that the pattern of lung capacity between COPD and PRISm changes over time29. But it’s worth noting that most of these studies have been conducted in Western populations, what’s more, most previous studies have assessed the prevalence5,30, risk factors31, and prognosis of PRISm10,11,32, but our study is the first retrospective study to predict the progression of PRISm in China. According to the study based on the Japanese population, the rate of progression is varied due to differences in patient background, such as smoking history, age and ethnicity. In Europe and the United States, COPD patients tend to be obese and non-emphysematous, while in East Asia, emphysema and emaciation are more common15. This further explains the necessity of exploring the risk factors of PRISm progression in our country. Our study also identified a subset of COPD patients who regained normal lung function or transitioned to PRISm, consistent with previous findings32. We propose three potential explanations for this phenomenon. First, lifestyle modifications and early interventions may delay or prevent disease progression. Second, the body’s inherent self-regulatory and repair mechanisms could contribute to functional recovery, particularly in patients without severe comorbidities. Third, instrumental variability might account for unstable lung function measurements in borderline cases. These findings highlight the importance of exploring PRISm progression risk factors within the context of China’s unique patient population.

Consistent with previous research, our study shows that the risk of PRISm progressing to COPD increases with age18,33. While age is a non-interventional factor, its significance underscores the importance of monitoring lung function from a young age, engaging in regular health check-ups, and initiating preventive interventions early in life to mitigate the risk of pulmonary function decline. Hye et al.‘s study further affirmed that in the overall sample, age, FVC, FEV1 pred, dyspnea, and wheezing were significant predictors of COPD and among PRISm patients, only age (OR, 1.14; P = 0.002) and wheezing (OR, 4.56; P= 0.04) emerged as significant predictors, which is consistent with our study14. Previous studies have shown a significant association between PRISm and dyspnea, and subjects complaining of dyspnea should be screened for PRISm and followed up on their lung function34. Our data confirm and extend these previous findings and identify additional risk factors for disease progression, enabling early screening of individuals in need of intervention.

At present, physicians often judge airflow limitation based on the decline of FEV1/FVC35. However, although FEV1/FVC is generally within the normal range for most patients with PRISm, our study suggests that a downward trend in this indicator may serve as a risk factor for disease progression. Additionally, patients with seemingly normal FEV1/FVC may not truly represent normal lung function and warrant further attention, confirming findings from previous research36. FEV1pred is a good indicator of moderate and severe airflow limitation. It is used to evaluate the classification and evaluation of the severity of airflow limitation in COPD. Due to its small variability and easy operation, it has been clinically used as a basic item in pulmonary function detection of COPD37. The reduction of FEV1pred was also found to be associated with the progression of pulmonary deterioration38. Our model incorporates this as one of the predictors, aligning with the current guideline recommendation to utilize the predicted percentage of FEV1 for classifying the severity of airflow obstruction. It also suggests that patients should be promptly alerted when a decline in predicted FEV1 is observed. In addition, our study has, for the first time, uncovered the impact of respiratory complications and elevated red blood cell count on the progression of PRISm, and these relationships can be further studied in the future.

There still exist several limitations in our study. First, the comorbidities of each system we collected were not detailed. Second, we lack a specific time interval for pulmonary function deterioration in patients. Third, while our diagnostic approach incorporated comprehensive clinical and imaging criteria to mitigate potential misclassification, the reliance on pre-bronchodilator spirometry remains a limitation. Future studies should adopt standardized post-bronchodilator testing to further reduce diagnostic uncertainty and enhance the validity of COPD phenotyping.Finally, since patients were not followed up regularly, we only included a small sample size of hospitalized patients for retrospective analysis, which may lead to some bias. For example, it is well known that previous/current smoking is a risk factor for worsening lung function, which has been confirmed in many studies29,39, but our model did not include this factor, which is due to the small retrospective sample size and cannot represent the characteristics of the entire population. Future multi - center longitudinal studies should establish external multi - center cohorts for external validation of model performance to identify more risk factors for PRISm progression and enhance the generalizability and reliability of research findings. Furthermore, future research should refine the assessment of comorbidities to explore the individual impact of each comorbidity on disease progression. Regular follow-up of PRISm patients is recommended for understanding the patterns and timing of changes, and early interventions should be implemented. This is the first study in China to predict the progression of PRISm, with a valuable prediction value. The model is well calibrated and the predictions have a strong correlation with the observed outcomes. Physicians can quickly identify PRISm patient who has higher risk of progression according to this simple prediction model.

Conclusion

PRISm is likely to progress to COPD, and older age, dyspnea, lower FEV1 pred, lower FEV1/FVC, respiratory complications and elevated red blood cell count are associated with PRISm progression. Further research is needed to help identify potential risk factors associated with PRISm progression as well as potential treatments and early intervention should be paid attention to in clinical practice to delay further deterioration of lung function.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Abbreviations

- ATS :

-

American Thoracic Society

- AUC:

-

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CIC:

-

Clinical impact curve

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DCA:

-

Decision curve analysis

- DLCO:

-

Diffusing capacity

- ERS:

-

European Respiratory Society

- FEV1 :

-

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- LLN:

-

Lower limit of normal

- NB:

-

Net benefit

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PFT:

-

Pulmonary function test

- Pre-COPD:

-

Pre-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- PRISm:

-

Preserved ratio impaired spirometry

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- TLC:

-

Total lung capacity

References

Celli, B. et al. Definition and nomenclature of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: time for its revision. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 206, 1317–1325 (2022).

GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global and National age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. (2018). Lancet (London, England) 392, 1736–1788 .

Agusti, A. & Faner, R. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease pathogenesis. Clin. Chest. Med. 41, 307–314 (2020).

Lange, P. et al. Lung-Function trajectories leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 111–122 (2015).

Wan, E. S. et al. Epidemiology, genetics, and subtyping of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) in COPDGene. Respir. Res. 15, 89 (2014).

Agustí, A. et al. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease 2023 report: GOLD Executive Summary. Eur. Respir. J. 61 (2023).

Guerra, S. et al. Health-related quality of life and risk factors associated with spirometric restriction. Eur. Respir. J. 49, 1602096 (2017).

Hankinson, J. L., Odencrantz, J. R. & Fedan, K. B. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. Population. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 159, 179–187 (1999).

Miura, S. et al. Preserved ratio impaired spirometry with or without restrictive spirometric abnormality. Sci. Rep. 13, 2988 (2023).

Wan, E. S. et al. Association between preserved ratio impaired spirometry and clinical outcomes in US adults. Jama 326, 2287–2298 (2021).

Higbee, D. H., Granell, R., Davey Smith, G. & Dodd, J. W. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications of preserved ratio impaired spirometry: a UK biobank cohort analysis. Lancet Respiratory Med. 10, 149–157 (2022).

Wijnant, S. R. A. et al. Trajectory and mortality of preserved ratio impaired spirometry: the Rotterdam study. Eur. Respir. J. 55, 1901217 (2020)

Tran, T. V. et al. Prevalence of abnormal spirometry in individuals with a smoking history and no known obstructive lung disease. Respir. Med. 208, 107126 (2023).

Wan, E. S. et al. Longitudinal phenotypes and mortality in preserved ratio impaired spirometry in the COPDGene study. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 198, 1397–1405 (2018).

Kanetake, R., Takamatsu, K., Park, K. & Yokoyama, A. Prevalence and risk factors for COPD in subjects with preserved ratio impaired spirometry. BMJ Open. Respiratory Res. 9, e001298 (2022).

Wan, E. S. et al. Significant spirometric transitions and preserved ratio impaired spirometry among ever smokers. Chest 161, 651–661 (2022).

He, D. et al. Different risks of mortality and longitudinal transition trajectories in new potential subtypes of the preserved ratio impaired spirometry: evidence from the english longitudinal study of aging. Front. Med. 8, 755855 (2021).

Park, H. J. et al. Significant predictors of medically diagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with preserved ratio impaired spirometry: a 3-year cohort study. Respir. Res. 19, 185 (2018).

Barnes, P. J. et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat. Reviews Disease Primers. 1, 15076 (2015).

Graham, B. L. et al. Standardization of spirometry 2019 update. An official American thoracic society and European respiratory society technical statement. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 200, e70–e88 (2019).

Vogelmeier, C. F. et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. GOLD executive summary. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 195, 557–582 (2017).

Mannino, D. M., Buist, A. S., Petty, T. L., Enright, P. L. & Redd, S. C. Lung function and mortality in the united States: data from the first National health and nutrition examination survey follow up study. Thorax 58, 388–393 (2003).

Mannino, D. M., Doherty, D. E. & Sonia Buist, A. Global initiative on obstructive lung disease (GOLD) classification of lung disease and mortality: findings from the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Respir. Med. 100, 115–122 (2006).

Mannino, D. M., Ford, E. S. & Redd, S. C. Obstructive and restrictive lung disease and functional limitation: data from the third National health and nutrition examination. J. Intern. Med. 254, 540–547 (2003).

Mannino, D. M. et al. Restricted spirometry in the burden of lung disease study. Int. J. Tuberculosis Lung Disease: Official J. Int. Union against Tuberculosis Lung Disease. 16, 1405–1411 (2012).

Culver, B. H. et al. Recommendations for a standardized pulmonary function report. An official American thoracic society technical statement. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 196, 1463–1472 (2017).

Stanojevic, S. et al. ERS/ATS technical standard on interpretive strategies for routine lung function tests. Eur. Respir. J. 60, 2101499 (2022).

Cestelli, L., Johannessen, A., Gulsvik, A., Stavem, K. & Nielsen, R. Risk factors, morbidity, and mortality in association with preserved ratio impaired spirometry and restrictive spirometric pattern: clinical relevance of preserved ratio impaired spirometry and restrictive spirometric pattern. Chest 167, 548–560 (2025).

Sood, A. et al. Spirometric variability in smokers: transitions in COPD diagnosis in a five-year longitudinal study. Respir. Res. 17, 147 (2016).

Guerra, S. et al. Morbidity and mortality associated with the restrictive spirometric pattern: a longitudinal study. Thorax 65, 499–504 (2010).

Schwartz, A. et al. Preserved ratio impaired spirometry in a spirometry database. Respir. Care. 66, 58–65 (2021).

Zheng, J. et al. Preserved ratio impaired spirometry in relationship to cardiovascular outcomes: A large prospective cohort study. Chest 163, 610–623 (2023).

Fan, J. et al. Potential pre-COPD indicators in association with COPD development and COPD prediction models in Chinese: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Western Pac. 44, 100984 (2024).

Kogo, M. et al. Longitudinal changes and association of respiratory symptoms with preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm): the Nagahama study. Annals Am. Thorac. Soc. 20, 1578–1586 (2023).

Vaz Fragoso, C. A. et al. Defining chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in older persons. Respir. Med. 103, 1468–1476 (2009).

Bhatt, S. P. et al. Discriminative accuracy of FEV1:FVC thresholds for COPD-Related hospitalization and mortality. Jama 321, 2438–2447 (2019).

Hegewald, M. J., Collingridge, D. S., DeCato, T. W., Jensen, R. L. & Morris, A. H. Airflow obstruction categorization methods and mortality. Annals Am. Thorac. Soc. 15, 920–925 (2018).

Bui, D. S. et al. Childhood predictors of lung function trajectories and future COPD risk: a prospective cohort study from the first to the sixth decade of life. Lancet Respiratory Med. 6, 535–544 (2018).

Parekh, T. M. et al. Factors influencing decline in quality of life in smokers without airflow obstruction: the COPDGene study. Respir. Med. 161, 105820 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We extremely appreciate the all members’ contribution to this study.

Funding

This study was supported by 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University(ZYGD22009 to W Li)and the Science and Technology Project of Sichuan (2022ZDZX0018 to W Li).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: W.M.L. and Y.L.L. Methods: J.X.W. and D.J.G Resources: J.X.W and L.Y. Data collection: J.X.W, H. H. Z , G.Q.W and J.H.X. Data analysis: G.Q.W. and J.X.W. Drafting the manuscript: J.X.W. Editing the manuscript: J.X.W, D.J.G , G.Q.W. and L.Y. Supervision: W.M.L. and Y.L.L. Funding acquisition: W.M.L. and Y.L.L.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The West China Hospital Research Ethics Committee and ethics committees approved the study (2023(1856)), which did not interfere with clinical management. Informed consent (oral or written) was obtained from study participants according to local requirements, except for cases in which a local committee granted a waiver or exemption. We adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, J., Wang, G., Gan, J. et al. Nomogram to predict progression from preserved ratio impaired spirometry to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Sci Rep 15, 10447 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93359-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93359-w