Abstract

To explore the potential role of serum calcium levels at admission in the expansion of acute traumatic intracerebral hematoma (tICH) and to construct a novel nomogram to predict tICH expansion. In this multicenter retrospective study, 640 and 237 patients were included in the training and validation datasets, respectively. Risk factors for acute tICH expansion were selected by logistic regression analysis. Causal mediation and interaction analysis were used to explore the relationship between serum calcium promotion of tICH expansion and inflammatory response. Receiver operating characteristic, calibration and clinical decision curves were applied to estimate the performance of multivariate models. Low serum calcium level was strongly associated with acute tICH expansion in patients with brain contusion. There was no significant interaction of hypocalcemia across multiple subgroups including sex, age, and coagulation dysfunction. 24.5% of the mechanisms by which hypocalcemia promotes acute tICH expansion can be explained by an inflammatory response. The addition of serum calcium made the modified model (serum calcium plus basic model) more accurate than basic model with subdural hematoma, multihematoma fuzzy sign, time to baseline CT, level on Glasgow Coma Scale score, platelet count, baseline tICH volume ≥ 5 mL, and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio. Low serum calcium level is a novel risk factor for acute tICH expansion, the mechanism of which may be mediated in part through the response of immune cell. The online dynamic nomogram provides a user-friendly tool for the prediction of acute tICH expansion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI), a major public health concern, is one of the leading causes of death and disability worldwide1. Approximately 44% of TBI patients have cerebral contusions, and 16%–75% of cerebral contusions have been reported to show hematoma progression on subsequent imaging2,3. Acute traumatic intraparenchymal hematoma (tICH) expansion is an early event following cerebral contusion, a serious and potentially life-threatening brain injury. Recognizing hematoma progression in hemorrhagic cerebral contusion is especially important because early detection and prompt treatment is associated with a reduced risk of complications and poorer outcomes4,5. Despite extensive research surrounding acute tICH, it remains an ongoing challenge to accurately predict the expansion of acute tICH1.

Currently, head computed tomography (CT) scans are the most commonly used method to assess primary hematoma volume and hematoma expansion. Baseline hematoma volume has been reported as a risk factor for hematoma enlargement6. The hematoma calculation method reported in many studies is calculated by 3D volume rendering. However, many hospitals currently still use the ABC/2 formula to calculate hematoma volume, which is much less accurate than that calculated by 3D volume rendering4. This limitation may result in less accurate measurement of primary hematoma volume, which in turn may affect the prediction of tICH hematoma expansion. In addition, some morphological indicators of hematoma on cranial CT images (e.g., multihematoma fuzzy sign) have been reported to have predictive value for hematoma enlargement, but the reliability and application value need to be confirmed by more studies7. Other predictors of tICH expansion, such as age8,9, coagulation dysfunction10, glucose levels11, and initial blood pressure12,13, also have limitations and need to be used in conjunction with other factors. Early identification of high-risk patients or early intervention to prevent the development of hematoma expansion is of great clinical and social importance to improve prognosis and improve the long-term survival of patients with TBI. Therefore, the identification of valuable risk factors for acute tICH expansion and the establishment of an accurate predictive model for acute tICH expansion is one of the current priorities in TBI research.

Abnormal serum calcium levels may reflect an imbalance in calcium homeostasis in the central nervous system, contributing to acute adverse progression. In recent studies, serum calcium levels that affect the progression of hematoma in patients with intracerebral hematoma have also been reported in hemorrhagic stroke, showing that serum calcium levels are negatively correlated with the amount of ICH, and associated with increased mortality and risk of progressive cerebral hemorrhaging14,15,16. In addition, serum calcium has been widely reported as a valuable prognostic marker in stroke17,18,19. Recently, studies have shown that hypocalcaemia on admission is associated with poor prognosis in patients with TBI20,21. However, the relationship between serum calcium and tICH expansion remains poorly understood. Given the heterogeneity of TBI, the mechanism by which low serum calcium affects hematoma progression is likely to be more complex than that of spontaneous ICH.

Immune cell response is a major feature of tICH following cerebral contusion22. After brain injury, the body can rapidly activate bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) through innervation, and generate monocytes with immune regulatory function in a short time23. When the body is under normal physiological conditions, the infiltration of peripheral immune cells into the brain is mainly limited by the blood-brain barrier (BBB). However, when a cerebral contusion occurs in the head, the BBB is destroyed and peripheral immune cells are able to infiltrate the brain from the periphery, leading to a process of injury24. It has been reported that extracellular fluid in the injured or infected area contains a high concentration of calcium, which may be significantly higher than the calcium concentration in serum, forming a concentration gradient with serum calcium concentration. The seven-transmembrane calcium-sensing receptor on mature monocytes/macrophages responds to this gradient of calcium concentration and leads to immune cell infiltration in the injured area through the damaged BBB25. In this study, a significant decrease in lymphocyte counts was also found in patients with hematoma expansion. In the acute phase expansion of tICH, the potential role of lymphocytes is complex and poorly understood, but low levels of lymphocyte counts suggest an association with spontaneous ICH progression and clinical deterioration26. In other diseases such as COVID-19, hypocalcemia is associated with decreased lymphocyte counts27. MLR reflects the changing balance between innate and adaptive immunity through the ratio of monocytes to lymphocytes, suggesting an indicator of the body’s immune status, which has been shown to have predictive value for acute tICH expansion28. Therefore, it seems reasonable to assume that MLR plays an important role in the impact of hypocalcemia on hematoma expansion.

In this study, we aim to (1) investigate the association of admission serum calcium level and tICH expansion after brain contusion, (2) explore the causal mechanisms behind the influence of serum calcium levels on acute tICH expansion from the perspective of immune cells’ response, and (3) develop and validate an easy-to-use clinical predictive tool, based on several admission characteristics, for acute tICH expansion.

Methods

Patient population and ethics

This retrospective cohort study was conducted in four hospitals between March 1, 2014, and February 1, 2019. The study included consecutive patients with primary TBI at three hospitals (the First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, and the Fuzong Clinical Medical College of Fujian Medical University, China) as the training dataset. Additionally, consecutive patients, between March 1, 2014, and October 1, 2020, with primary TBI at the Affiliated Jieyang Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University were retrospectively included in the external validation cohort.

Patients in all TBI centers were treated according to the Chinese surgical guidelines for management of traumatic brain injury to reduce heterogeneity among multiple centers29. Inclusion criteria were: (1) baseline CT scan showing at least one intraparenchymal hematoma, (2) adult patient (age > 18 years), and (3) having an isolated TBI lesion without severe injury to other regions. Exclusion criteria were: (1) baseline CT scan more than 6 h after brain contusion, (2) no follow-up CT scan within 48 h after baseline CT scan, (3) surgical clearing of hematoma or death before follow-up CT, (4) history of brain tumor or spontaneous ICH, (5) lack of a blood test within 24 h after brain contusion, and (6) used anticoagulants or had coagulopathy related diseases before TBI.

The ethics committees of the four hospitals mentioned above approved this study with an ethical approval number (No. 2020-042). The study has been registered on https://www.researchregistry.com/ and the Research Registry Unique Identifying Number is researchregistry 9420. The work has been reported in line with the STROCSS criteria. As this was a retrospective study, the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College approved the waiver of informed consent. The ethical standards and regulations in the relevant version of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed for all procedures in this study30.

Demographic and clinical variable assessment

Variables were obtained from the hospital’s electronic medical record systems, including sex, age, cause of injury, hypertension, mean arterial pressure (MAP), diabetes mellitus, smoking, drinking, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, and in-hospital death. Venipuncture was performed on admission to collect venous blood samples. Routine blood tests and biochemical tests were conducted to determine platelet count, leukocyte count, lymphocyte count, and monocyte count, serum calcium levels, and blood glucose. Routine coagulation tests were also performed on admission to determine the prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), international normalized ratio (INR), and fibrinogen level21.

Imaging acquisition and processing

Axial non-contrast CT images were obtained according to a standardized local protocol at each participant’s institution. The CT images were read and recorded by two neurosurgeons with more than 10 years of experience to ensure the reliability and accuracy of the data. Patient clinical data were kept confidential to them to avoid bias. The location and morphology of the ICH and the presence of epidural hematoma (EDH), subdural hematoma (SDH), subarachnoid hematoma (SAH), and intraventricular hematoma (IVH) were recorded based on baseline CT images. CT images were analyzed using semi-automated computer-assisted volumetric analysis software (General Electric Company, Waukesha, WI, USA) to calculate the hematoma volume of the tICH. In addition, baseline CT time and follow-up CT time were recorded31. When the hematoma occurred in more than one region of the brain, only the region with a hematoma volume greater than 5 ml was recorded. When the volume of the hematoma increased in a region, it was registered as the volume of the hematoma in that region. If there was no hematoma enlargement, the total volume was calculated when multiple intraparenchymal hematomas were detected in the contusion area.

Definitions in this study

Acute tICH expansion was defined as an absolute increase of ≥ 6 mL in the hematoma size or a relative increase of ≥ 33%32,33. This is due to the fact that a 33% change in sphere volume corresponds to a 10% increase in diameter, which is significantly different from what is seen by the naked eye of physicians observing serial CT scans of patients with ICH. GCS scores were classified into three levels: mild TBI (GCS score:13–15), moderate TBI (GCS score: 9–12), and severe TBI (GCS score: 3–8)34. Hypocalcemia was a serum calcium level below 2.10 mmol/L35. Patients were considered to have a coagulation disorder if the APTT was ≥ 36 s, the INR was > 1.2, or the platelet count was < 120 × 109 platelets/L at admission10. To better represent the odds ratio of serum calcium level to acute tICH expansion, the ratio of serum calcium level to the standard deviation of total group calcium level (Ca/Ca.S.D.) was used for the logistic regression analysis21. MLR is the ratio of monocyte count to lymphocyte count.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with the commercially available SPSS software version 26 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA) and R statistical software (version 4.1.0, R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) with appropriate R packages36. Variables were compared in the patients with and without acute tICH expansion. Continuous variables were represented by the means (standard deviations), and categorical variables were represented by numerical values (percentages)36. The chi-square test was applied to categorical data, Student’s t-test to normally distributed variables, and the Mann-Whitney U test to nonparametric data. Missing data in this study were few and completely missing at random. For missing data, multiple imputation was used to generate complete data sets from the data set containing missing values36. All tests of significance in this study were two-tailed, and statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

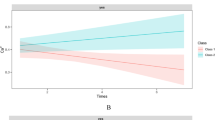

Mediation effect analysis was performed according to the relevant codes in the literature and the “mediation” R package. In the training dataset, we validated the effect of serum calcium levels on acute tICH expansion in each subgroup (including sex, age, GCS, SDH, baseline tICH volume, coagulation function, MLR) on acute tICH expansion by subgroup analysis, and by cross-tabulation analysis of additive models were used to calculate the interactions. Finally, Causal mediation analysis (CMA) was used to investigate whether MLR proportionally mediated the effect of hypocalcemia on acute tICH expansion events. CMA is a method that decomposes the total effect of a variable into direct and indirect effects. In CMA, the average causal mediation effect (ACME) is the average effect transmitted through the mediating variable (M), while the average direct effect (ADE) is the effect through all other pathways other than M37. In this approach, hypocalcemia was assumed to be the exposure factor (X), MLR was assumed to be the mediator (M), and acute tICH expansion was used as the outcome (Y). For the mediation analysis, there were three pathways essential to test (Fig. 4A): pathway-c, where X is associated with Y; pathway-a, where X is associated with M; and pathway-b, where M is associated with Y after adjusting for X. When the associations of all three pathways were confirmed, mediation (indirect effects) can be determined in the fourth step by estimating direct causality (Fig. 4A, pathway-c’). The ACME and the ADE were estimated using a nonparametric 1000 bootstrap method.

Logistic regression analysis was applied to identify potential risk factors for acute tICH expansion. Independent risk factors with P < 0.05 were first selected by univariate regression analysis using a forward selection procedure and then included in a multivariate model. Additionally, in subgroup analysis, logistic regression analysis to investigate the relationship between serum calcium levels and acute tICH expansion in different subgroups, and the interaction test was performed to explore the interaction between subgroup and serum calcium in acute tICH expansion.

Two models were developed to predict acute tICH expansions based on multivariate logistic regression: a basic model and a modified model (with the addition of serum calcium to the variables incorporated in the basic model). A nomogram was generated from the modified model in the validation cohort. The method of nomogram generation and application was described in our previous study36.

The discriminative power of the prediction model and nomogram was evaluated in terms of the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), and the difference between various model AUCs was determined using the DeLong test. Calibration curves were plotted with actual and predicted probabilities as described in previous studies36,38. Additionally, decision curve analysis (DCA) was applied to assess the clinical utility of the model39. DCA is a method to evaluate the application value of predictive models in actual clinical decision making. It is achieved by comparing the net benefits of different decision alternatives within a specific threshold range. Here “net benefit” refers to the net effect after taking into account the benefits and losses from false positive and false negative results. The central principle of DCA is to quantify the utility of predictive models at specific clinical decision thresholds and compare them with other decision strategies. To facilitate the application of the prediction model, we upgraded the nomogram to a dynamic nomogram and uploaded it to the shinyapps.io platform (https://dzzhuang.shinyapps.io/tich_expansion/)40,41.

Results

Characteristics of patients with acute tICH

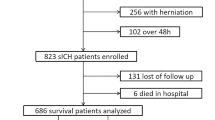

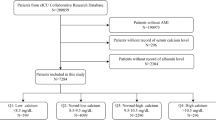

There were 640 patients enrolled in the development database (Fig. 1A), with a mean age of 50 years, of whom 505 (78.9%) were male. Among them, 299 (46.7%) had acute tICH extension. Patients with acute tICH extension had a higher mean age, leukocyte count, and MLR than those without extension. There were no significant differences in sex, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, epidural hematoma, brain atrophy, and location of brain contusion between the two groups. Additionally, they had a larger baseline tICH volume and follow-up tICH volume, a longer PT and APTT, a lower serum calcium level and lymphocyte count, and reduced time to baseline CT scan and baseline CT to follow-up CT scan. Patients with tICH expansion were more likely to have higher motor vehicle-related injuries, in-hospital mortality, IVH, SAH, SDH, large baseline tICH volume, hypocalcemia, and severe or moderate GCS levels compared with patients without hematoma expansion (Table 1).

Flowchart of the patient selection process, including inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients in the training dataset (A) were retrospectively selected from the First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, and the Fuzong Clinical Medical College of Fujian Medical University between March 1, 2014, and February 1, 2019. Patients in the validation dataset (B) were selected from the Affiliated Jieyang Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University between March 1, 2014, and October 1, 2020.

The 237 patients included in the validation dataset had a mean age of 52 years, and 184 (77.6%) were male (Fig. 1B). Of these, 128 (54.0%) had acute tICH expansion. Similar to the training dataset, patients with acute tICH expansion had lower serum calcium levels and a higher frequency of hypocalcemia compared to patients without acute tICH expansion (Table S1).

Admission predictor selection and construction of predictive models for acute tICH expansion

Univariate logistic and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to construct the outcome model for predicting hematoma enlargement in tICH patients. Univariate logistic regression showed that age, Glasgow Coma Scale score, location of contusion, IVH, SAH, SDH, time to baseline CT, baseline tICH volume ≥ 5 mL, multihematoma fuzzy sign, PT, INR, APTT, platelet count, MLR, and serum calcium levels were the independent risk factors of acute tICH expansion (Table S2). These variables were then included in a multivariate regression model, and after adjusting for confounders, the p-values for GCS level (adjusted OR: 1.60, 95% CI: 0.91–2.80, moderate vs. mild; adjusted OR: 1.71, 95% CI: 1.02–2.86, severe vs. mild), SDH (adjusted OR: 2.40, 95% CI: 1.51–3.81), platelet count (adjusted OR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.99-1.00), MLR (adjusted OR: 7.22, 95% CI: 4.20-12.42), multihematoma fuzzy sign (adjusted OR: 7.22, 95% CI: 6.32–24.67), time to baseline CT (adjusted OR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.80–0.97), baseline tICH volume ≥ 5 mL (adjusted OR: 1.87, 95% CI: 1.08–3.22), and serum calcium level (adjusted OR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.42–0.68) remained significant. Finally, two predictive models (basic, and modified models) were conducted (Table 2). Among the two models, the basic model incorporated Glasgow Coma Scale score, SDH, platelet count, MLR, multihematoma fuzzy sign, time to baseline CT and baseline tICH volume ≥ 5 mL, and variables from the basic model and serum calcium level were included in the modified model.

Low serum calcium is an independent risk factor for acute tICH expansion

Based on the results of univariate logistic regression, an association between serum calcium levels (Ca/Ca.S.D.) and acute tICH expansion was found (Table S2). Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that after adjusting for other independent risk factors for acute tICH expansion, serum calcium levels remained significant (Table 2). Moreover, no significant interactions were found between serum calcium and any of the subgroup variables, including sex, age, GCS level, coagulation, baseline tICH volume, and MLR (Fig. 2).

Assessment of model predictive value

The predictive models were compared using ROC curve analysis. The modified model (AUC: 0.858, 95% CI: 0.829–0.888) exhibited optimal discrimination for acute tICH expansion compared with the models of serum calcium (AUC: 0.694, 95% CI: 0.653–0.735) and the basic model (AUC: 0.833, 95% CI: 0.801–0.866) (Fig. 3A). Moreover, the calcium model had a higher sensitivity (75.78% vs. 72.66%) and specificity (81.90% vs. 80.95%) compared with the basic model. Calibration curves were used to evaluate the performance of these models further. Calibration curves showed that both the basic model and modified model exhibited excellent calibration for patients with tICH (Fig. 3B). In DCA, both basic and modified models had certain clinical practicality with net benefit between threshold probabilities of 30% and 100%, and the modified model seemed to have a higher net benefit compared to the basic model (Fig. 3C). In an external validation dataset, the modified model maintained better discrimination for acute tICH expansion compared with the basic model (AUC: 0.871, 95% CI: 0.827–0.916 vs. AUC: 0.830, 95% CI, 0.779–0.881; P = 0.01) (Fig. 3D). Both the modified model and basic model for acute tICH expansion maintained excellent calibration (Fig. 3E). The DCA results also showed that the modified nomogram showed a superior net clinical benefit in predicting acute tICH expansion (Fig. 3F).

Discrimination, calibration and clinical benefit of models for acute tICH expansion. (A) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed for the basic model (red line), modified model (blue line) and serum calcium (green line) for the prediction of acute tICH expansion in the training cohort. (B) DCA curve of basic and full model predicted acute tICH expansion. The modified model shows a higher net benefit in the training cohort. (C) The consistency of the modified model is better than that of the basic model in the training cohort. (D) ROC curve analysis was performed for the basic model (red line), modified model (blue line), and serum calcium (green line) for the prediction of acute tICH expansion in the validation cohort. (E) DCA curve of basic and full model predicted acute tICH expansion. The modified model shows a higher net benefit in the validation cohort. (F) The consistency of the modified model is better than that of the basic model in the validation cohort.

Altogether, the modified model had better clinical utility in terms of discrimination, calibration, and tICH expansion compared to the basic model and single serum calcium. The subgroup-specific classification performance of the basic model and modified nomogram was validated in different subgroups (comprising sex, age, GCS classification, initial hematoma volume class, MLR level, coagulopathy, hypocalcemia, and SDH) (Table 3). Subgroup-specific classification performance indicated that the modified nomogram seemed to have better discriminatory ability in most subgroups compared to the basic model, and exhibited good performance in terms of sensitivity and specificity (Table 3).

Mediation analysis of MLR between hypocalcemia and acute tICH expansion

In the CMA, it was necessary to test three pathways (Fig. 4A), after which the mediation effect could be determined. First, mediation analysis was used to test the hypothesis that coagulation dysfunction mediates hypocalcemia to acute tICH expansion. The results showed that coagulation did not pass the pathway a (X→M) test. MLR was further found to play a partially mediating role in the effect of hypocalcemia on acute tICH expansion in tICH patients (Fig. 4B). In the unadjusted model, the mediating variable MLR explained 24.5% (95% CI: 13.9–39.0%; P < 0.001) of the effect in acute tICH expansion by hypocalcemia. This mediating effect decreased slightly to 22.2% (95% CI: 11.8–36.0%; P < 0.001) in the adjusted model (Table S3).

Nomogram construction

For clinical application, a nomogram for predicting tICH expansion was built on the modified models (Fig. 5). In the nomogram, the sum of the scores of each index for each patient corresponds to the probability of tICH expansion. Finally, the nomogram was upgraded to a dynamic nomogram and uploaded to the shinyapps. io platform at https://dzzhuang.shinyapps.io/tich_expansion/. Users can calculate the probability of tICH expansion for each patient via computer or cell phone (Fig. 6). After the output of the sample is calculated, the results page will show the probability of tICH expansion, 95% confidence interval and the parameters of the model.

Nomogram from the modified model for acute tICH expansion. Points for each parameter are assigned by corresponding values from the point axis to calculate a patient’s risk of acute tICH expansion. The sum of the points is plotted on the total point axis. The patient’s acute tICH expansion probability is the value at the vertical line from the corresponding total points.

Discussion

This multicenter retrospective study examined the relationship between serum calcium levels at admission and acute tICH expansion and explored the possible mechanisms behind it from an inflammatory perspective. Serum calcium levels were significantly lower in patients with acute tICH expansion than in those without expansion, and the frequency of hypocalcemia was higher. Low serum calcium levels on admission are an independent risk factor for acute tICH expansion, and this association occurs in a broad group of tICH patients. CMA results indicate that MLR (an immune cell response index) may partially mediate the effect of hypocalcemia on acute tICH expansion with a mediating contribution of 24.5%. We further developed two predictive models for acute tICH expansion in patients with hemorrhagic cerebral contusion, the basic model and modified model based on the basic model incorporating the variable serum calcium. The modified model showed optimal discrimination, and clinical utility compared with the basic model. Finally, we presented a modified nomogram in external validation. This nomogram maintained excellent performance in both discrimination and calibration in the externally validated dataset and showed a good net benefit for clinical purposes.

In clinical practice, the progression of ICH is a dynamic and complex phenomenon, and its underlying pathophysiology remains unclear. Previous studies suggest that inflammatory response, hypertension and impaired coagulation may be key pathways driving ICH progression10,14. Serum calcium is one of the important physiological indicators in the human body. Firstly, serum calcium levels can affect vascular reactivity. Secondly, serum calcium plays an important role in coagulation cascades. In non-tICH patients, low serum calcium levels on admission indicate a larger baseline hematoma volume, a higher risk of hematoma enlargement, poorer prognosis, and coagulation dysfunction may be the underlying mechanism14,15,42.

In this study, low serum calcium is also a risk factor for hematoma enlargement. Similar to spontaneous ICH, recent reports have suggested that low serum calcium levels may play an important role in hematoma progression in tICH through coagulation dysfunction, with a partial mediating effect of coagulation function explaining 24.4% of the total effect43. In present study, we did not find an interactive effect of serum calcium and coagulation function on acute tICH expansion. However, in contrast to the study of Zhang and colleagues43, we did not find a mediating effect of coagulation function, which may be due to differences in patient selection criteria and outcome definitions. For instance, Zhang and colleagues included patients who had a baseline CT within 8 h of injury and a follow-up CT within 24 h of the baseline CT, whereas this study included patients who had a baseline CT within 6 h after injury and a follow-up CT within 48 h after the baseline CT, and there were also some differences in the definition of outcomes, as our outcome variable, hematoma expansion, did not include features of a new hematoma found at the follow-up CT, whereas this was included in the definition of outcomes in Zhang’s study. Moreover, Zhang’s results were based on a single-center and as such may have sources of bias and variation. Therefore, more relevant studies are needed to verify the mediating role of coagulopathy in hypocalcemia on hematoma progression.

The current study further explores MLR as a mediator and its interaction with hypocalcemia on acute tICH expansion. The results showed that no significant interaction was found between serum calcium and MLR in terms of hematoma enlargement, which implies that the relationship between the variables was additive rather than multiplicative. Through CMA, MLR was found to serve as a partial mediator of the effect of hypocalcemia on acute tICH expansion. This finding highlights the key role played by immune cells’ responses in the development of acute tICH expansion. Serum calcium levels may influence the inflammatory index MLR, which in turn partially mediates the effect of acute tICH expansion. Specifically, MLR accounts for 24.5% of the effect of serum calcium on acute tICH expansion. Understandably, immune cells’ response only partially mediates the effect of serum calcium on acute tICH expansion. This suggests that serum calcium may have additional effects through unrecognized pathways44. Animal studies suggest that in ischemic brain injury, calcium migrate from the serum to affected areas, resulting in a slight increase in extracellular calcium concentration and activation of calcium-sensitive receptors, which in turn initiate anti-apoptotic pathways45,46. Calcium supplementation has also been found to reduce stroke mortality rates in rats47. Furthermore, a decrease in calcium levels may disrupt the adhesiveness and tightness of endothelial cells, thereby affecting the integrity of the BBB and potentially exacerbating bleeding48,49. Overall, our findings provide a new perspective on the role of serum calcium levels in the mechanism of immune cells’ response-induced acute tICH expansion, using MLR as a point of entry. However, this study only proposed hypotheses, and validation and testing about mechanisms can only be realized by further designing experimental protocols or through other studies.

Hematoma expansion is a significant factor contributing to unfavorable outcomes in traumatic brain injury (TBI). Even minor changes in hematoma volume can lead to functional impairment4. Over the years, models have been proposed to predict acute tICH expansion, with recent improvements. In a retrospective cohort study involving 468 cases, a predictive model was developed to anticipate hematoma progression after TBI, using admission indicators such as age, brain contusion, midline shift ≥ 5 mm, platelet count, prothrombin time, D-dimers, glucose, and this model shows a good performance in discrimination (C statistic = 0.864)9. Another retrospective analysis of 107 patients with tICH also created a model to predict hematoma progression by incorporating variables such as age, multiple traumatic intraparenchymal hematoma, SDH, injury severity score, INR, and initial hematoma volume. By incorporating radiomic scores into the model with a machine learning algorithm, the model demonstrated excellent predictive performance (AUC = 0.83)6.

In the present study, we developed a model to predict acute tICH expansion using patient blood indicators, imaging data, demographic characteristics, and clinical variables. Univariate regression analysis showed that variables, such as age, hypertension, contusion location, IVH, SAH, coagulation dysfunction, PT, APTT, and INR, are associated with acute tICH expansion. However, multivariate regression did not confirm these associations and, therefore, are not entered into the modified model/nomogram interpretation. The modified model shows good discriminatory power (AUC = 0.858) and generates a user-friendly nomogram with variables such as SDH, multihematoma fuzzy sign, baseline CT time, MLR, and serum calcium level. The Glasgow Coma Scale level, a baseline tICH volume ≥ 5 ml, and platelet count were not included in the modified model because they did not contribute significantly to predictive performance. The discriminatory power of this nomogram was further validated in different subgroups. In addition, the modified nomogram is based on easily available clinical variables and non-enhanced CT images that can be easily replicated in other trauma centers. More importantly, the nomogram in this study can generate an online calculator through the shinyapps.io platform. Clinicians only need to enter the patient’s data into the corresponding data frame, and the probability of tICH occurrence will be calculated automatically. Doctors do not need to manually calculate the scores of each factor on the nomogram, which greatly improves the efficiency of doctors and the accuracy of results, and is more convenient for clinical promotion.

The management and treatment of hemorrhagic brain contusion is highly individualized. The present study includes a large sample size from multiple centers, external validation design, well-characterized patients with brain contusion, and quantitatively measured pathological and clinical variables to provide a solid foundation for reliable and robust predictive models. Low-risk patients can benefit from avoiding unnecessary intensive monitoring and overtreatment. High-risk patients can benefit from the use of safe and cost-effective treatments, including discontinuation of medications such as anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents50,51, removal of hematomas or decompression to reduce intracranial pressure52, and strict blood pressure control to reduce the risk of further bleeding53. The targeted involvement of latent or other coagulation disorders has prompted attempts to reverse such coagulation disorders, using agents such as recombinant factor VIIa. However, the efficacy of recombinant factor VIIa is controversial54, and Zaaroor et al. suggest that hemostatic therapy after traumatic brain injury may be beneficial for specific subgroups of patients55. Factor VIIa is the second component along with tissue factor that rapidly accelerates blood clotting through an exogenous pathway. Calcium is required for this response, which proceeds by activating factor X to form factor Xa56. Serum calcium levels are associated with increased hematoma, and attention to serum calcium levels may also provide some reference for the use of recombinant factor VIIa.

In the future, a multicenter prospective controlled study is warranted to explore the causal relationship among hypocalcemia, MLR, and tICH. Secondly, appropriate animal experiments can be designed to verify the possible mechanism of low calcium promoting tICH through immune cells proposed in this study.

Limitations

The current study has several limitations as follows. First, we used a retrospective design and some patients were not included in our dataset due to various missing clinical data, so this study is subject to selection and information bias inherent in its design. Although this study used multivariate logistic regression analysis to control for confounders, stratified and propensity analyses may be more effective for controlling for confounders and could be used in subsequent studies. Second, ionized calcium or corrected calcium is a better indicator of biological function than serum calcium57. However, there is a lack of data on ionized calcium. Given the good correlation between serum calcium levels and ionized calcium levels, low serum calcium levels may partially reflect abnormal biological function15,58. Further, the hypothesis that low calcium levels mediate the inflammatory response to promote hematoma enlargement, as suggested by the mediating effect analysis in this study, requires further design of clinical studies or experimental validation. Finally, the use of modified nomograms in clinical decision-making should be approached with caution, as it is not intended to replace a surgeon’s clinical assessment of the patient but rather serves as a supplementary tool to aid the surgeon in their evaluation.

Conclusion

Low serum calcium level at admission is associated with acute tICH expansion. The mediator MLR (an index of immune cells’ response) explains 24.4% of the effect of low serum calcium level on acute tICH expansion. The modified nomogram provides an accessible tool to support the individualized treatment and management of patients with hemorrhagic brain contusion.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request fromthe corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy orethical restrictions.

References

Maas, A. I. R. et al. Traumatic brain injury: integrated approaches to improve prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 12 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30371-X (2017).

Volpe, J. J. Injuries of extracranial, cranial, intracranial, spinal cord, and peripheral nervous system structures. Volpe’s Neurol. Newborn. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-42876-7.00036-3 (2018).

Adatia, K., Newcombe, V. F. J. & Menon, D. K. Contusion progression following traumatic brain injury: A review of clinical and radiological predictors, and influence on outcome. Neurocrit. Care. 34 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-020-00994-4 (2021).

Fletcher-Sandersjöö, A. et al. Time course and clinical significance of hematoma expansion in Moderate-to-Severe traumatic brain injury: an observational cohort study. Neurocrit Care. 38 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-022-01609-w (2023).

Kurland, D., Hong, C., Aarabi, B., Gerzanich, V. & Simard, J. M. Hemorrhagic progression of a contusion after traumatic brain injury: A review. J. Neurotrauma. 29 https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2011.2122 (2012).

Shih, Y. J. et al. Prediction of Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage Progression and Neurologic Outcome in Traumatic Brain Injury Patients Using Radiomics Score and Clinical Parameters. Diagnostics 12, (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12071677

Sheng, J. et al. Development and external validation of a novel multihematoma fuzzy sign on computed tomography for predicting traumatic intraparenchymal hematoma expansion. Sci. Rep. 11 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81685-8 (2021).

Oertel, M. et al. Progressive hemorrhage after head trauma: predictors and consequences of the evolving injury. J. Neurosurg. 96 https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2002.96.1.0109 (2002).

Yuan, F. et al. Predicting progressive hemorrhagic injury after traumatic brain injury: derivation and validation of a risk score based on admission characteristics. J. Neurotrauma. 29 https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2011.2233 (2012).

Maegele, M. et al. Coagulopathy and haemorrhagic progression in traumatic brain injury: advances in mechanisms, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Neurol. 16 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30197-7 (2017).

Wan, X. et al. Association of APOE Ε4 with progressive hemorrhagic injury in patients with traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Neurosurg. 133 https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.4.JNS183472 (2020).

Vedantam, A., Yamal, J. M., Rubin, M. L., Robertson, C. S. & Gopinath, S. P. Progressive hemorrhagic injury after severe traumatic brain injury: effect of hemoglobin transfusion thresholds. J. Neurosurg. 125 https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.11.JNS151515 (2016).

Wan, X. et al. Progressive hemorrhagic injury in patients with traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage: characteristics, risk factors and impact on management. Acta Neurochir. (Wien). 159 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-016-3043-6 (2017).

Morotti, A. et al. Association between serum calcium level and extent of bleeding in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. JAMA Neurol. 73, 1285–1290. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.2252 (2016).

Inoue, Y., Miyashita, F., Toyoda, K. & Minematsu, K. Low serum calcium levels contribute to larger hematoma volume in acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 44, 2004–2006. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001187 (2013).

Jafari, M., Di Napoli, M., Datta, Y. H., Bershad, E. M. & Divani, A. A. The role of serum calcium level in intracerebral hemorrhage hematoma expansion: is there any?? Neurocrit Care. 31, 188–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-018-0564-2 (2019).

Appel, S. A. et al. Serum calcium levels and long-term mortality in patients with acute stroke. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 31 https://doi.org/10.1159/000321335 (2010).

Zhang, J. F. et al. Serum calcium and long-term outcome after ischemic stroke: results from the China National stroke registry III. Atherosclerosis 325, 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2021.03.030 (2021).

Tu, L. et al. Admission serum calcium level as a prognostic marker for intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 30, 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-018-0574-0 (2019).

Badarni, K. et al. Association between admission ionized calcium level and neurological outcome of patients with isolated severe traumatic brain injury: A retrospective cohort study. Neurocrit Care. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-023-01687-4 (2023).

Li, T. et al. Low serum calcium is a novel predictor of unfavorable prognosis after traumatic brain injury. Heliyon 9 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18475 (2023).

Sulhan, S., Lyon, K. A., Shapiro, L. A. & Huang, J. H. Neuroinflammation and blood–brain barrier disruption following traumatic brain injury: pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets. J. Neurosci. Res. 98 https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.24331 (2020).

Shi, S. X., Shi, K. & Liu, Q. Brain injury instructs bone marrow cellular lineage destination to reduce neuroinflammation. Sci. Transl Med. 13 https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abc7029 (2021).

Yong, V. W., Power, C. & Edwards, D. R. Metalloproteinases in biology and pathology of the nervous system. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2 https://doi.org/10.1038/35081571 (2001).

Olszak, I. T. et al. Extracellular calcium elicits a chemokinetic response from monocytes in vitro and in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 105 https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI9799 (2000).

Liesz, A., Hu, X., Kleinschnitz, C. & Offner, H. Functional role of regulatory lymphocytes in stroke: facts and controversies. Stroke 46 https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008608 (2015).

Alemzadeh, E., Alemzadeh, E., Ziaee, M., Abedi, A. & Salehiniya, H. The effect of low serum calcium level on the severity and mortality of Covid patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 9 https://doi.org/10.1002/iid3.528 (2021).

Sheng, J. et al. The Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte ratio at hospital admission is a novel predictor for acute traumatic intraparenchymal hemorrhage expansion after cerebral contusion. Mediators Inflamm. 2020 https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5483981 (2020).

Chinese Congress of Neurological Surgeons. Chinese surgical guidelines for management of traumatic brain injury. [J]. Chin. J. Neurosurg. 25, https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-2346.2009.02.003 (2009).

Mathew, G. et al. STROCSS 2021: strengthening the reporting of cohort, cross-sectional and case-control studies in surgery. Int. J. Surg. 37 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.106165 (2021).

Delgado Almandoz, J. E. et al. Systematic characterization of the computed tomography angiography spot sign in primary intracerebral hemorrhage identifies patients at highest risk for hematoma expansion: the spot sign score. Stroke 40 https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.554667 (2009).

Rosa, M. J. et al. Contusion contrast extravasation depicted on multidetector computed tomography angiography predicts growth and mortality in traumatic brain contusion. J. Neurotrauma. 33 https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2015.4062 (2016).

Yao, X., Xu, Y., Siwila-Sackman, E., Wu, B. & Selim, M. The HEP score: A Nomogram-Derived hematoma expansion prediction scale. Neurocrit Care. 23 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-015-0147-4 (2015).

Brennan, P. M., Murray, G. D. & Teasdale, G. M. Simplifying the use of prognostic information in traumatic brain injury. Part 1: the GCS-Pupils score: an extended index of clinical severity. J. Neurosurg. 128 https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.12.JNS172780 (2018).

Soar, J. et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Sect. 8. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances: Electrolyte abnormalities, poisoning, drowning, accidental hypothermia, hyperthermia, asthma, anaphylaxis, cardiac surgery, trauma, pregnancy, electrocution. Resuscitation 81 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.015 (2010).

Sheng, J. et al. A clinical predictive nomogram for traumatic brain parenchyma hematoma progression. Neurol. Ther. 11 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-021-00306-8 (2022).

Tofighi, D. & MacKinnon, D. P. RMediation: an R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behav. Res. Methods. 43 https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x (2011).

Pencina, M. J. & D’Agostino, R. B. Evaluating discrimination of risk prediction models: the C statistic. JAMA 3142 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.11082 (2015).

Zhuang, D. et al. A dynamic nomogram for predicting unfavorable prognosis after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ann. Clin. Transl Neurol. 10 https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.51789 (2023).

Zhuang, D. et al. A dynamic nomogram for predicting intraoperative brain Bulge during decompressive craniectomy in patients with traumatic brain injury: a retrospective study. Int. J. Surg. 110 https://doi.org/10.1097/JS9.0000000000000892 (2024).

Li, T. et al. A dynamic online nomogram for predicting death in hospital after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Eur. J. Med. Res. 28 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-023-01417-8 (2023).

You, S. et al. Serum calcium and phosphate levels and Short- and Long-Term outcomes in acute intracerebral hemorrhage patients. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 25 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.12.023 (2016).

Zhang, P. et al. Association between serum calcium level and hemorrhagic progression in patients with traumatic intraparenchymal hemorrhage: investigating the mediation and interaction effects of coagulopathy. J. Neurotrauma. 39 https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2021.0388 (2022).

Kristián, T. & Siesjö, B. K. Calcium in ischemic cell death. Stroke 29 https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.29.3.705 (1998).

Jensen, B., Farach-Carson, M. C., Kenaley, E. & Akanbi, K. A. High extracellular calcium attenuates adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Exp. Cell. Res. 301 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.08.030 (2004).

Lin, K. I. et al. Elevated extracellular calcium can prevent apoptosis via the calcium-sensing receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 249 https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1998.9124 (1998).

Peuler, J. D. & Schelper, R. L. Partial protection from salt-induced stroke and mortality by high oral calcium in hypertensive rats. Stroke 23 https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.23.4.532 (1992).

Alexander, J. S., Blaschuk, O. W. & Haselton, F. R. An N-cadherin–like protein contributes to solute barrier maintenance in cultured endothelium. J. Cell. Physiol. 156 https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.1041560321 (1993).

Brown, R. C. & Davis, T. P. Calcium modulation of adherens and tight junction function: A potential mechanism for blood-brain barrier disruption after stroke. Stroke 33 https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.0000016405.06729.83 (2002).

Feng, M. et al. Endovascular embolization of intracranial aneurysms: to use Stent(s) or not?? Systematic review and Meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 93 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2016.06.014 (2016).

Pandya, U., Malik, A., Messina, M., Albeiruti, A. R. & Spalding, C. Reversal of antiplatelet therapy in traumatic intracranial hemorrhage: does timing matter? J. Clin. Neurosci. 50 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2018.01.073 (2018).

Mendelow, A. D. et al. Early surgery versus initial Conservative treatment in patients with traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage (STITCH[Trauma]): the first randomized trial. J. Neurotrauma. 32 https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2014.3644 (2015).

Qureshi, A. I. et al. Intensive Blood-Pressure Lowering in patients with acute cerebral hemorrhage. N. Engl. J. Med. 375 https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1603460 (2016).

Al-Shahi Salman, R., Law, Z. K., Bath, P. M., Steiner, T. & Sprigg, N. Haemostatic therapies for acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst. Reviews. 17 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005951.pub4 (2018).

Zaaroor, M. et al. Administration off label of Recombinant factor-VIIa (rFVIIa) to patients with blunt or penetrating brain injury without coagulopathy. Acta Neurochir. (Wien). 150 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-008-1593-y (2008).

Mikaelsson, M. E. The role of calcium in coagulation and anticoagulation. Coagulation Blood Transfus. 26 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-3900-1_3 (1991).

Sava, L., Pillai, S., More, U. & Sontakke, A. Serum calcium measurement: total versus free (ionized) calcium. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 20 https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02867418 (2005).

Wang, X. et al. Association between serum calcium and prognosis in patients with acute pulmonary embolism and the optimization of pulmonary embolism severity index. Respir Res. 21 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-020-01565-z (2020).

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2022A1515012144, 2023A1515012055), Joint Logistics Medical Key Specialty Program (LQZD-SW), and the Fujian Provincial Science and Technology Innovation Joint Fund (2019Y9045).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dongzhou Zhuang, Tian Li, Xianqun Wu, Kangsheng Li, Shousen Wang, and Weiqiang Chen, designed the study. Tian Li, Dongzhou Zhuang, Xianqun Wu, Huan Xie, Xiaoxuan Chen, Fei Tian, Hui Peng, and Shousen Wang collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. Tian Li, Dongzhou Zhuang, and Jiangtao Sheng drafted the manuscript. Tian Li, Jiangtao Sheng, Weiqiang Chen, Kangsheng Li, Dongzhou Zhuang, Fei Tian, Hui Peng, and Shousen Wang advised on the preparation of the manuscript. All authors read, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

The Ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College approved this study, and the ethics approval number was 2020-042. The study has been registered on https://www.researchregistry.com/ and the Research Registry Unique Identifying Number is researchregistry9420. The work has been reported in line with the STROCSS criteria. As this was a retrospective study, the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College approved the waiver of informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhuang, D., Li, T., Wu, X. et al. Low serum calcium promotes traumatic intracerebral hematoma expansion by the response of immune cell: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 8639 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93416-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93416-4