Abstract

Cross-border driving can lead to differences in driving behavior due to factors such as driving regulations and vehicle configurations, which subsequently impact traffic efficiency and safety. Approximately 69% of countries and regions worldwide follow right-hand traffic (RHT) rules and use left-hand drive (LHD) vehicles, while the remainder follow left-hand traffic (LHT) rules and use right-hand drive (RHD) vehicles. Cross-border driving creates a mixed-traffic scenario involving both LHD and RHD. However, the differences in driving behavior between these two vehicle types and their impacts on traffic flow characteristics remain poorly understood. Here, we show that by utilizing license plate recognition data from the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, we have developed an integrated macroscopic and microscopic traffic analysis framework. This framework allows us to analyze individual-level driving behavior differences and quantify their effects on overall traffic performance under both real-world and simulated conditions. Our findings reveal that RHD and LHD vehicles exhibit distinct driving behavior patterns, and these differences persist in the long term. The coexistence of RHD and LHD vehicles can reduce road capacity by approximately 15%. Thus, managing mixed traffic requires attention to behavioral differences and the penetration rates of heterogeneous vehicles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With socio-economic development, the surge in cross-border travel has led to situations where travelers may encounter driving rules opposite to their own, requiring them to integrate into traffic systems where steering wheels are positioned on the opposite side. Due to historical, cultural, geographical, and neighboring influences, some countries and regions use left-hand drive (LHD) vehicles while adhering to right-hand traffic (RHT) rules, whereas others follow the reverse pattern. The differences in traffic rules are illustrated in Fig. 1. Previous studies have demonstrated that changes in traffic regulations and vehicle configurations can affect driver behavior1. One notable consequence is the rise in road traffic accidents associated with increased cross-border travel2. Ergonomic and visibility issues for drivers3 may arise from mismatches between traffic rules and vehicle configurations, potentially raising the likelihood of collision. The study by Bari et al.4 confirmed that the relative risk of personal injury caused by LHD trucks, compared to similar right-hand drive (RHD) vehicles operating in the UK, was 61%. Ma et al.5 and Das et al.6 argued that the driver’s performance is reflected in both the lateral and longitudinal control of the vehicle, which directly influences lane-changing and car-following behaviors (De La Fuente et al.7). This indicates that driving is a complex dynamic control activity involving human psychological processes and physical workload, including a large amount of information processing, which leads to high cognitive load (Wiberg et al.8). Dijksterhuis et al.9 found that the increase in event complexity leads to an increase in cognitive load, which can result in difficulties in movement and, ultimately, inappropriate actions or even traffic accidents10. To further investigate the internal effects of mismatched vehicles and traffic rules on driving behavior, some researchers applied the average measurements of the ‘A’ and ‘B’ pillars of LHD vehicles to RHD models. The results showed that the unobstructed visibility between the ‘A’ and ‘C’ pillars on the left side of LHD vehicles was reduced by approximately 40%11, which is expected to significantly increase the risk of lane changes. Eye-tracking studies under different traffic rules have shown that while gaze distribution in the central forward region is generally consistent between LHT (left-hand traffic) and RHT, significant differences emerge in gaze frequency and duration within the central regions. In the upper and lower right regions of the center, LHT drivers exhibited significantly higher gaze frequency and duration compared to RHT drivers, whereas eye movements were more active in the upper and lower left regions under RHT conditions12. Research4 indicates that RHD vehicles pose a significantly higher collision risk compared to LHD vehicles, though the severity of these collisions does not differ significantly. A study13 based on four years of national panel data from 54 African countries found that road fatalities were lower in countries with left-hand traffic rules.

Differences in rules between left-hand and right-hand traffic systems. In (a), an LHD vehicle follows an RHT system, where the rule is to drive on the right side and use the left lane for overtaking. In (b), an RHD vehicle follows an LHT system, driving on the left with the right lane as the overtaking lane.

In addition to the objective impact of mismatches between vehicles and traffic regulations on driving behavior, a driver’s mental load and the complexity of the driving environment also influence their behavior. Studies have shown that when drivers encounter complex road environments, each driving event triggers a specific level of cognitive workload depending on its complexity and the surrounding conditions (e.g., road design, layout, and traffic flow). Increased complexity can impair performance due to heightened mental burden14. Lewis et al.15 explained the relationship between driving orientation and traffic safety from a neurophysiological perspective. The results provided evidence from neuropsychology, demonstrating that left-hand driving is safer than right-hand driving. However, some scholars argue that right-hand driving is safer. For instance, Wei et al.16 found that under right-hand driving rules, response times were shorter and safe distances were longer compared to left-hand driving rules. They suggested that the subtle differences between left-hand and right-hand driving are related to the dominance of the eyes, and conducted overtaking tests to explore the safety of road rules from the perspective of safe distances. As active implementers of driving behavior, drivers who comply with vehicle-traffic rules can significantly affect driving safety. When drivers are unfamiliar with vehicle configurations, coupled with challenges related to manual operations (such as manual gear shifting) or visibility issues, they may make temporary adjustments that increase the likelihood of collisions (Cooper et al.10). Therefore, transitioning from one set of traffic rules to another can complicate driving. Engström et al.17 proposed the cognitive control hypothesis, suggesting that as task demands increase, drivers tend to maintain their preferred (optimal) speed, deviating from or approaching the speed indicated in the experiment. Moreover, tourists driving in unfamiliar traffic conditions often struggle to focus on critical driving-related information and areas, a phenomenon particularly pronounced when they are exposed to traffic practices different from those in their home country18. For instance, after navigating a curve, drivers may subconsciously increase their following distance to allow for a longer reaction time, leading to unstable following behavior19. Simulators have been used to investigate the effects of right- and left-hand driving on behavior in unfamiliar environments. For example, studies have shown that Japanese drivers, accustomed to right-hand traffic, are more prone to lane departures when driving on left-hand traffic roads. Additionally, significant differences in gap distances were observed between right- and left-hand driving scenarios20. While unfamiliar traffic rules do not significantly impair lane maintenance, they may result in shorter exposure to danger during short-term driving21. Cultural and social differences can also prompt drivers from different regions to adjust their habits and become more cautious, reducing aggressive driving behaviors22. Consequently, when these drivers are involved in single-vehicle crashes, the severity of injuries tends to be lower. Similarly, cross-border drivers are often less confident and less likely to engage in risky driving behaviors compared to local drivers, who are more familiar with the environment23.

Differences in driving behavior can impact road capacity and traffic stability15,24, directly influencing efficiency and safety metrics, making it a focal point in the study of mixed traffic flows25,26,27. Some studies suggest that factors such as headway distance28, reaction time29, and penetration rates of heterogeneous vehicles in mixed traffic30,31,32 directly affect road capacity, and variations in driving behavior may induce and propagate oscillations33, potentially exacerbating congestion near bottlenecks34. However, these findings are largely based on autonomous driving scenarios35. For example, Mohammed et al.36-37 investigated the impact of Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) systems on driver behavior, visibility, and traffic capacity through real-vehicle experiments. Research on the characteristics of mixed traffic flow arising from cross-border travel in scenarios involving RHD and LHD vehicles remains largely unexplored. This gap can be attributed to two main factors: the scarcity of extensive real-world scenarios featuring RHD and LHD vehicles mixed traffic as a foundational basis for study, and the lack of understanding regarding the differences in driving behavior between the two vehicle types within mixed traffic flow.

Although it has been found that differences in traffic rules, vehicle configurations, individual drivers’ physiological and psychological conditions, and driving habits38 contribute to varying driving behaviors during cross-border travel, the research on the driving behavior patterns of cross-border drivers and their differences remains limited (e.g., Harootunian et al.39, Yoh et al.40). Previous literature has primarily focused on the differences in road traffic accident risks between foreign drivers across national borders. The conclusions drawn suggest that foreign drivers crossing national boundaries may experience higher accident rates (e.g., Yoh et al.40) or may be more prone to causing severe accidents (e.g., Nævestad et al.41, Alogaili and Mannering42). Most of these studies are confounded by variables such as language barriers, cultural differences, or the quality of infrastructure. While some scholars have examined the risks faced by drivers crossing domestic borders (e.g., Cézard et al.43), the impact of hardware differences in infrastructure quality and software differences in social and legal systems on cross-border driving risks in specific countries/regions, in the absence of language and cultural differences, requires further investigation. Moreover, there is currently no practical evidence capturing and quantifying these driving behavior differences, nor how these differences impact traffic flow operations. Research in this area remains insufficient. In this study, we aim to bridge this research gap by quantifying differences in driving behavior during cross-border travel using real-world data.

This study focuses on developing a cognitive model of driving behavior and a mixed traffic flow analysis framework to explore the differences in driving behavior during cross-border travel and their impact on traffic flow. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

-

1.

A comprehensive analysis framework for cross-border mixed traffic flow is established. This framework enables the investigation of how behavioral differences among heterogeneous vehicles under various driving rules influence traffic flow.

-

2.

At the cognitive level, an online calibration-based traffic simulation model is developed, which facilitates the recognition of behavioral differences among heterogeneous vehicles in cross-border travel.

-

3.

At the application level, utilizing a high-fidelity traffic simulation model, the impact of heterogeneous vehicle penetration rates on traffic flow capacity and congestion propagation speed is examined. Additionally, a method for calculating the penetration rate threshold at the minimum traffic capacity is proposed.

Methods

In this study, we present a mixed traffic flow analysis framework for LHD and RHD vehicles, as illustrated in Fig. 2. This framework consists of three modules: spatiotemporal computation, behavioral cognition, and characteristic analysis.

The spatiotemporal computation module reconstructs the travel trajectory of individual vehicles from a vast amount of license plate recognition data, extracting trip time, average speed, and other data information, which serves as the data foundation for subsequent research. Based on this data, the behavioral cognition module identifies the driving behavior differences between LHD and RHD vehicles. Finally, in combination with these behavioral differences, the characteristic analysis module further explores the traffic flow characteristics when LHD and RHD vehicles mix.

illustrates the analytical framework for mixed traffic flow involving LHD and RHD vehicles. In the first spatiotemporal computation module, the collection and preprocessing of license plate recognition data are conducted, allowing for an understanding of the spatiotemporal distribution of cross-border travel, thereby providing a foundational dataset for subsequent research. The behavioral modeling module employs mathematical statistics to directly analyze observable differences in driving behavior, followed by the identification of unobservable behavioral differences through microscopic traffic simulation modeling. Finally, in the feature analysis module, the impact of heterogeneous vehicle penetration rates, characterized by the aforementioned differences in driving behavior, on mixed traffic flow is examined, including effects on road capacity and the evolution of traffic conditions. *Map creation software: QGIS 3.42, https://qgis.org/downloads/QGIS-OSGeo4W-3.34.15-1.msi.

Spatiotemporal computation of cross-border travel

To promote economic growth in the Bay Area44, the government implemented the “Two Vehicles Northbound” policy in 202345. This has led to a unique phenomenon in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, where a significant number of RHD vehicles from Hong Kong and Macao intermingle with LHD vehicles in Guangdong Province, particularly on the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge46. This situation involves changes in traffic regulations, providing a realistic context and data foundation for this study. We collected license plate recognition data from 20,000 cameras and 6,438 electronic toll collection (ETC) devices in Guangdong Province between 2023 and 2024, encompassing information such as license plate numbers, timestamps, vehicle colors, segment numbers, device IDs, longitude, and latitude, as well as accident information. Sample data is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Data processing adhered to the following criteria: (i) License plate numbers must exceed eight digits or be non-empty; (ii) Timestamps must fall between July 1, 2023, and June 30, 2024; (iii) Duplicate license plate numbers detected at the same point are removed; (iv) Duplicate license plate numbers appearing at different points simultaneously are removed; (v) License plate numbers that appear only once are removed, except at border entry and exit points. Then, according to the traffic time order and upstream and downstream relationship in the road network topology, vehicle trajectories are generated in turn. Vehicles with an interval of less than one hour are considered part of the same trip.

Behavioral cognition of driving

The driving behavior cognition model quantitatively assesses the behavioral differences between LHD and RHD vehicles within mixed traffic flows, encompassing both observable explicit differences and unobservable implicit differences.

Recognition of explicit driving behavior differences

The most direct method for observing driving behavior is through speed measurement. We utilize vehicle speed to investigate the explicit differences between RHD and LHD vehicles. The speed calculation is detailed in Eq. (1):

where\(\:\:{l}_{OD}\) represents the length of the road segment,\(\:\:{t}_{D}\) is the time when the vehicle leaves the segment, and \(\:{t}_{O}\) is the time when the vehicle enters the segment.

The relative speed difference between RHD and LHD vehicles, denoted as \(\:\varDelta\:v\), along with the standard deviation of this relative difference over various periods, \(\:\sigma\:\), are calculated using Eqs. (2) and (3):

Here, \(\:{v}_{RHD,i}\) represents the speed of RHD vehicles, \(\:{v}_{LHD,i}\) represents the speed of LHD vehicles, and \(\:{\stackrel{-}{\varDelta\:v}}_{i}\) is the average of the relative speed differences between RHD and LHD vehicles.

Recognition of implicit driving behavior differences

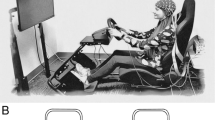

The differences in latent driving behavior manifest as explicit speed variations, prompting the development of a driving behavior cognitive model. This model is based on a microscopic traffic simulation platform, aiming to minimize the error between simulated and real speeds48. Through optimization algorithms, it calibrates parameters characterizing lateral and longitudinal movements47, capturing the driving behavior characteristics of RHD and LHD vehicles within mixed traffic flow. The simulation modeling component utilizes SUMO as the experimental platform, encompassing demand modeling, network modeling, and vehicle movement modeling. The optimization algorithm involves sensitivity analysis of model parameters and parameter calibration. This two-stage algorithm design efficiently determines parameter importance, narrowing the solution space for specific optimization. The detailed steps are illustrated in Fig. 3. Additionally, we use the root mean square error between simulated and real speeds, as criteria for evaluating simulation accuracy. The experimental data comprises travel records of all vehicles on the northbound segment from Honghu Interchange to Nanping Interchange between 10:00 and 12:00 on March 29, 2024, a period that witnessed the highest cross-border travel volume due to Easter.

Driving Behavior Cognition Model. The driving behavior cognition model consists of two primary modules: microscopic traffic simulation modeling and parameter calibration. These modules interact iteratively through the TraCI interface to achieve high-precision simulations and to analyze differences in driving behavior within mixed traffic flow. Parameter calibration involves two phases: sensitivity analysis and parameter optimization. In Phase One, a decision tree model is used to assess the sensitivity of parameters. If the sensitivity level is less than or equal to the threshold \(\:\epsilon\:\), it indicates that the parameters are optimal or near-optimal solutions; if it exceeds the threshold \(\:\epsilon\:\), further optimization is required. The sensitivity threshold \(\:\epsilon\:\) is set at 0.1.

Micro traffic simulation module

Network modeling utilizes the netconvert tool from the SUMO platform, with the mapping method detailed in Supplementary Tables 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2. Demand modeling constructs individual-level travel spatiotemporal paths, generating vehicle trajectories sequentially based on the chronological passage of vehicles through the network topology and their upstream-downstream relationships49. This paper focuses on vehicle motion models.

Vehicle motion modeling

The microscopic driving dynamics of highway vehicles are determined by the interaction between following models and lane-changing models. The following sections detail how parameters within these motion models control vehicle driving behavior.

-

1.

Following model

This study employs the default Krauss following model from SUMO to describe longitudinal vehicle movement50. Following behavior is primarily controlled by six parameters:

Acceleration (accel) governs the vehicle’s maximum acceleration capability, typically applied during lane changes or when reaching desired speeds. The formula for velocity change during acceleration is:

$$\:{v}_{new}={v}_{current}+accel\cdot\:t$$(4)where \(\:{v}_{new}\) is the updated vehicle speed,\(\:\:{v}_{current}\) is the current speed, \(\:accel\) is the acceleration value, and\(\:\:t\) is the time interval.

Deceleration (decel) determines the maximum deceleration capability of the vehicle, utilized for emergency braking or reducing speed to maintain a safe distance. The formula is:

$$\:{v}_{new}={v}_{current}-decel\cdot\:t$$(5)where \(\:decel\) is the vehicle’s deceleration.

After acceleration or deceleration, the driver’s final traveling speed is primarily determined by the speed factor (\(\:speedFactor\)) and a randomness coefficient (\(\:\sigma\:\)). The speedFactor controls the driver’s individualized speed choice, adjusting speed preferences (e.g., 1.1 indicates a 10% overspeed). The randomness coefficient (\(\:\sigma\:\)) reflects random fluctuations in driver behavior, enhancing the realism of the simulation. Thus, the formula for the final traveling speed \(\:v\) is:

$$\:v={v}_{desired}\cdot\:speedFactor\cdot\:\left(1+\sigma\:\cdot\:\mathcal{N}\left(\text{0,1}\right)\right)$$(6)where \(\:{v}_{desired}\) is the desired speed, \(\:\sigma\:\) is the randomness coefficient, and \(\:\mathcal{N}\left(\text{0,1}\right)\) is a normally distributed random variable.

To ensure safe following distances, the vehicle reaction time \(\:\tau\:\) and the vehicle’s minimum safe distance (\(\:minGap\)) are utilized. \(\:\tau\:\) controls the time delay from detecting the need for action to actual operation. Consequently, the relationship controlling safe following distance is expressed as:

$$\:{d}_{safe}=minGap+v\cdot\:\tau\:+\frac{{v}^{2}}{2\cdot\:decel}$$(7)where \(\:{d}_{safe}\) is the safe following distance, \(\:minGap\) is the minimum safe distance, \(\:v\) is the vehicle speed, and \(\:\tau\:\) is the reaction time.

-

2.

Lane-changing model

In this study, we utilize SUMO’s default LC2013 lane-changing model to describe lateral vehicle movements51. The following parameters collectively influence lane-changing decision-making.

The lcStrategic parameter controls the propensity for strategic lane changes, determining whether a vehicle will proactively switch lanes to achieve long-term driving goals. This is typically associated with the vehicle’s target lane and assesses whether a lane change is necessary, such as when approaching an exit. The decision involves identifying a target lane, and the strategic lane-change utility can be expressed as:

$$\:\text{Strategic}\text{\_}\text{utility}=lcStrategic\cdot\:{f}_{\text{target\:lane}}$$(8)where \(\:{f}_{\text{target\:lane}}\) is a target lane evaluation function based on current and future traffic conditions.

The lcCooperative parameter reflects the degree to which a vehicle cooperates with others during lane changes, particularly in multi-lane scenarios. For example, when a following vehicle attempts to change lanes, the leading vehicle may adjust its speed to facilitate the maneuver. Cooperative utility is evaluated by:

$$\:\text{Cooperative}\text{\_}\text{utility}=lcCooperative\cdot\:{f}_{\text{cooperation}}$$(9)where \(\:{f}_{\text{cooperation}}\) represents factors such as inter-vehicle distance and speed differentials, assessing whether cooperation enhances traffic efficiency.

The lcSpeedGain parameter evaluates the potential speed advantage from a lane change, indicating whether a vehicle can accelerate after changing lanes. A larger value reflects a stronger motivation to change lanes for speed gains. The speed gain utility is expressed as:

$$\:\text{SpeedGain}\text{\_}\text{utility}=lcSpeedGain\cdot\:\frac{{v}_{\text{new\:lane}}-{v}_{\text{current\:lane}}}{{v}_{\text{current\:lane}}}$$(10)where \(\:{v}_{\text{new\:lane}}\) and \(\:{v}_{\text{current\:lane}}\) are the speeds in the target and current lanes, respectively.

The lcKeepRight parameter indicates a vehicle’s tendency to prefer the rightmost lane, influencing decisions to remain or move towards the right. This behavior is governed by:

$$\:\text{Right}\text{\_}\text{utility}=lcKeepRight\cdot\:{f}_{\text{right\:preference}}$$(11)where \(\:{f}_{\text{right\:preference}}\) represents lane usage rules and the preference for right lanes on specific road segments.

The lcAssertive parameter regulates how assertive a driver is during lane changes. Higher values lead to more proactive decisions, such as changing lanes under smaller inter-vehicle distances or larger speed differentials. Assertive utility is defined as:

$$\:\text{Assertive}\text{\_}\text{utility}=lcAssertive\cdot\:\frac{{d}_{\text{min}}}{{d}_{\text{safe}}}$$(12)where \(\:{d}_{\text{min}}\) is the distance to the leading vehicle, and \(\:{d}_{\text{safe}}\) is the safe following distance.

Lastly, the lcCooperativeSpeed parameter combines cooperation with speed gain, influencing a vehicle’s willingness to coordinate with others while maintaining speed. The cooperative speed utility is given by:

$$\:\text{CooperativeSpeed}\text{\_}\text{utility}=lcCooperativeSpeed\cdot\:{f}_{\text{speed\:cooperation}}$$(13)where \(\:{f}_{\text{speed\:cooperation}}\) assesses the speed gains resulting from cooperative lane changes.

Together, these parameters govern lane-changing and car-following behaviors, enabling the simulation of personalized driving strategies.`.

Parameter calibration module

The parameter calibration process follows a two-stage approach using a “decision tree + whale optimization algorithm” model. In Stage 1, a decision tree model assesses the sensitivity of driving behavior parameters under coupled changes, providing an initial solution. Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 present experimental results based on the control variable method, showing that results from individual parameter changes are less intuitive and accurate compared to those under parameter coupling conditions. The experimental design involves randomly generating n value levels within each parameter’s range, where n is 30 times the number of parameters52. Ten sets of 360 iterative simulations were conducted, and the solution with the minimum root mean square error (RMSE) was selected as optimal. Parameter value ranges are provided in Supplementary Information Table 2. In Stage 2, the whale optimization algorithm further calibrates the highly sensitive parameters to precisely simulate traffic flow, and the input values of the parameters required by the algorithm are shown in supplementary Table 5. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6, the simulation error decreased from 13 to 9% after this stage. The solutions obtained from both stages are summarized in Supplementary Table 4. The methods are detailed below.

For the decision tree model, parameter sensitivity is calculated using the formula:

where \(\:t\) is a given node, \(\:i\) represents any class of labels, \(\:c\) is the total number of label categories, and \(\:p\left(i \left| \right. t\right)\) is the proportion of category \(\:i\) at node \(\:t\).

The whale optimization algorithm is adopted due to its simplicity, fewer control parameters, and strong ability to escape local optima53. This algorithm mimics whale hunting behaviors: encircling prey, bubble-net attacking, and searching for prey. The modeling process is outlined below.

-

1.

Encircling prey:

In a \(\:d\)-dimensional space, the current best whale \(\:{X}^{\text{*}}\) has coordinates \(\:\:({X}_{1}^{\text{*}},{X}_{2}^{\text{*}},{X}_{3}^{\text{*}},\dots\:,{X}_{d}^{\text{*}})\) in a population of size \(\:N\), and whale \(\:{X}^{j}\) is located at \(\:({X}_{1}^{j},{X}_{2}^{j},{X}_{3}^{j},\dots\:,{X}_{d}^{j})\). The next position of whale \(\:{X}^{j}\), denoted as \(\:{X}^{j+1}\), is updated by the following formula:

$$\:{X}_{k}^{j+1}={X}_{k}^{\text{*}}-{A}_{1} \cdot {D}_{k}$$(15)$$\:{D}_{k}=\left|{C}_{1}\cdot\:{X}_{k}^{\text{*}}-{X}_{k}^{j}\right|$$(16)where \(\:{C}_{1}=2{r}_{2}\), \(\:{A}_{1}=2a\cdot\:{r}_{1}-a\), \(\:a=2-2t/{T}_{max}\). Here, \(\:{D}_{k}\) is the absolute difference, \(\:a\) decreases linearly from 2 to 0 with iteration \(\:t\), and \(\:{T}_{max}\) is the maximum number of iterations. Both \(\:{r}_{1}\) and \(\:{r}_{2}\) are random numbers between 0 and 1.

-

2.

Bubble-net attacking:

-

a.

Shrinking encircling: This behavior is almost identical to encircling prey, except that \(\:{\text{A}}_{1}\)’s value range is adjusted to [-1, 1] to reflect the shrinking.

-

b.

Spiral updating: Whales also swim towards the prey in a spiral pattern. At a 50% probability, the next position is updated as:

$$\:{X}_{k}^{j+1}=\left\{\begin{array}{c}{X}_{k}^{j+1}={X}_{k}^{\text{*}}-{A}_{1} \cdot {D}_{k}\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:P<0.5\\\:{X}_{k}^{j+1}={X}_{k}^{\text{*}}-{D}_{k}\cdot\:{\text{e}}^{bl}\cdot\:\text{cos}\left(2\pi\:l\right)\:\:\:p\ge\:0.5\end{array}\right.$$(17)$$\:{D}_{k}=\left|{X}_{k}^{\text{*}}-{X}_{k}^{j}\right|$$(18)where \(\:b\) is a constant defining the logarithmic spiral, and \(\:l\) is a random number between − 1 and 1.

-

a.

-

3.

Global search:

To avoid local optima, a random search mechanism is applied. The next position is updated as:

$$\:{X}_{k}^{j+1}={X}_{k}^{rand}-{A}_{1}\cdot{D}_{k}$$(19)$$\:{D}_{k}=\left|{C}_{1}\cdot\:{X}_{k}^{rand}-{X}_{k}^{j}\right|$$(20)where \(\:{X}_{k}^{rand}\) represents the position vector of a randomly selected whale.

Analysis of mixed traffic flow characteristics

Fundamental macroscopic models of mixed traffic flow

The macroscopic fundamental diagram effectively reflects the operational patterns of traffic networks, solving dimensionality issues in large-scale road networks. It can derive key parameters such as road capacity and optimal density. Two main methods exist for estimating the MFD: analytical54,55,56,57 and empirical methods58. However, analytical methods rely on assumptions that may not align with real-world conditions59. Hence, this study estimates the MFD using data from traffic simulators60.

Based on simulation data, the relationship between flow and density follows the Underwood exponential model:

where \(\:{v}_{f}\) is the free-flow speed, \(\:{k}_{m}\) is the optimal density, \(\:q\) is the flow, and \(\:k\) is the density. MFD models are constructed for mixed traffic flow under varying RHD vehicle penetration rates.

Indicators of traffic flow evolution characteristics

Vehicle operating speed reflects the stability of traffic flow61, while congestion propagation speed describes the transition from free-flow to congestion. Two metrics are proposed to characterize the evolution of mixed traffic flow:

-

1.

Variance of average speed over the free-flow-to-congestion process:

$$\:{{\upalpha\:}}_{speed}=\frac{1}{NT}\sum\:_{t=1}^{T}\sum\:_{n=1}^{N}{\left({\stackrel{-}{v}}_{n}\right(t)-\frac{1}{N}\sum\:_{n=1}^{N}{\stackrel{-}{v}}_{n}\left(t\right))}^{2}$$(22)where \(\:{\stackrel{-}{v}}_{n}\left(t\right)\) is the average speed of vehicle \(\:\text{n}\) at time \(\:\text{t}\).

-

2.

Congestion propagation speed:

$$\:{w}_{ij}=\frac{{q}_{i}-{q}_{j}}{{k}_{i}-{k}_{j}}$$(23)where \(\:{w}_{ij}\) is the speed of congestion propagation between states \(\:i\) and \(\:j\).

Results

Through the spatiotemporal calculation module in the methodology, we obtained the spatial distribution and accident distribution of RHD and LHD vehicles in mixed traffic in the real world, as shown in Fig. 4a.ii and 4a.iii. Figure 4a.i displays the device locations where these license plates were collected. Further exploration was conducted on specific road segments in Zhuhai, where the RHD distribution is most concentrated and the accident rate is highest, to analyze the differences in driving behaviors under mixed traffic conditions. At the same time, a total of 5,854,002 vehicle track data were obtained after data processing. We also found that approximately 40,000 RHD vehicles travel in Guangdong Province daily, with a higher concentration in Zhuhai, particularly in areas directly connected to the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge (Supplementary Fig. 1). This serves as our simulation study area. (The experimental data comprises travel records of all vehicles on the northbound segment from Honghu Interchange to Nanping Interchange between 10:00 and 12:00 on March 29, 2024, a period that witnessed the highest cross-border travel volume due to Easter.)

Explicit driving behavior refers to driving performance that can be directly observed, recorded, or measured externally, such as speed. In contrast, implicit behaviors are traits that are more challenging to identify through direct observation. Differences in these behaviors arise from multiple factors, including drivers’ awareness of traffic regulations, adaptability to the environment, and individual driving habits. By studying the behavioral differences between cross-border drivers—specifically those operating RHD and LHD vehicles—we can gain deeper insights into the origins of these differences and their underlying mechanisms.

Explicit differences in driving behavior within mixed traffic flow

Through the “Recognition of Explicit Driving Behavior Differences” section in the second module of the methodology, we obtained the speeds of RHD and LHD vehicles within the study area. Figure 4b illustrates the overall distribution of these two speed categories across different periods. Additionally, Table 1 presents the characteristic values of the two speed types: maximum, median, and minimum values, along with the average relative difference \(\:\varDelta\:v\) and the standard deviation of the relative difference \(\:\sigma\:\). Compared to LHD vehicles, RHD vehicles exhibit a higher overall speed and greater dispersion, indicating significant volatility. The average speed of RHD vehicles is 7% higher than that of LHD vehicles, while its minimum speed is 11% lower; however, its maximum speed exceeds that of LHD vehicles by 29%. According to traffic flow characteristics, when traffic volume is low, the flow tends to be smooth, allowing vehicles to operate at higher speeds. Conversely, during periods of high traffic volume, congestion results in reduced speeds. Therefore, we infer that RHD vehicles tend to “drive quickly” within a range of 0–29% above LHD vehicles speeds when traffic is light, while “driving slowly” within a range of 0–11% below LHD vehicles speeds during heavy traffic conditions. This also indirectly reflects RHD vehicles’ lack of adaptation to speed limits when faced with unfamiliar traffic environments and rules, as well as their cautious driving behavior in heavy traffic situations. This hypothesis is substantiated in the subsequent analysis of implicit differences.

While previous studies have indicated that drivers experience a noticeable reduction in cognitive load and improvement in lane-keeping ability as driving time increases under unfamiliar traffic rules19, our research based on real data reveals that speed differences between RHD and LHD vehicles persist over time (from the first to the fourth quarter), with fluctuations remaining within 6%. This suggests that differences in driving behavior may be long-standing rather than merely a consequence of short-term adaptation issues. The multifaceted influences of the environment, vehicle configuration, and traffic rules contribute to the sustained significant differences in the driving behavior of RHD vehicles over the course of a year.

Characteristics of cross-border travel for RHD vehicles (Vehicles from Hong Kong and Macau). This figure illustrates the spatial distribution of cross-border travel for vehicles from Hong Kong and Macau, the distribution of accidents, and observable speed differences compared to vehicles from the mainland. (a.i) displays the locations of equipment used to capture individual vehicle travel trajectories. (a.ii) and (a.iii) present the spatial distribution of cross-border travel and the occurrence of accidents for vehicles from Hong Kong and Macau, respectively. (b) shows the statistical distribution of speeds for RHD and LHD vehicles across each quarter (2023–2024, divided into four quarters) since the implementation of the “Northbound Policy for Vehicles from Hong Kong and Macau.” *Map creation software: QGIS 3.42, https://qgis.org/downloads/QGIS-OSGeo4W-3.34.15-1.msi.

Implicit differences in driving behavior within mixed traffic flow

Using the “Recognition of Implicit Driving Behavior Differences” in the second module of the methodology, we reveal the implicit behavioral differences between RHD and LHD vehicles. Supplementary Table 1 provides a detailed description of the parameters governing vehicle driving behavior39, while Supplementary Table 4 presents their corresponding result values. All parameter values in Fig. 5 have been normalized.

The driving behavior cognitive experiment reveals that LHD vehicles exhibit higher sensitivity to speed control parameters (speedFactor), reaction time control parameters (tau), and randomness control parameters (sigma), indicating a greater perception of these three types of parameters. In contrast, RHD vehicles are less sensitive to the reaction time control parameter (tau), as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Regarding longitudinal movement, the minimum safe distance (minGap) between RHD vehicles and the preceding vehicle is 3.79 m, significantly higher than LHD’s 2.97 m. The reaction time (tau) for RHD vehicles is 1.74 s, also exceeding that of LHD vehicles at 1.46 s. This difference arises from the increased cognitive load faced by RHD vehicles when encountering unfamiliar traffic rules and road conditions, leading to instability in their vehicle-following behavior. Consequently, they subconsciously increase their following distance to extend their reaction time. Furthermore, the cooperativeness in speed adjustment (lcCooperativeSpeed) in mixed traffic flow is lower for RHD vehicles compared to LHD vehicles. Although the overall speed (speedFactor) and acceleration (accel) of RHD vehicles are higher than those of LHD vehicles, their deceleration (decel) is lower. This suggests that RHD vehicles are less inclined to perform emergency braking. The driving randomness (sigma) indicates that RHD vehicles exhibit a more cautious and steady driving style.

In terms of lateral movement, the rightward driving preference (lcKeepRight) of RHD vehicles reaches 8.99, markedly higher than LHD vehicles’ 2.66. This difference can be attributed to the traffic rules that RHD vehicles adhere to, such as Hong Kong’s traffic management regulations, which require vehicles to overtake on the right in fast lanes and prohibit heavy trucks from using the right lane48. These discrepancies in fast lane rules make RHD vehicles more likely to drive in the right lane, while LHD vehicles prefer to drive at high speeds in the left lane. When LHD vehicles are sparse, they typically travel at high speeds in the left lane, whereas RHD vehicles are accustomed to high-speed driving in the right lane, often exceeding LHD vehicles speeds. However, when LHD vehicles are traveling slowly in the right lane, RHD vehicles must proceed cautiously. This indirectly supports the conclusion in Fig. 4b that RHD vehicles are faster than LHD vehicles at high speeds but slower at low speeds. Additionally, the tendencies for cooperative lane changes (lcCooperative) and strategic lane changes (lcStrategic) are nearly identical; however, RHD vehicles’ willingness to change lanes (lcSpeedGain) is lower, reflecting their caution in unfamiliar driving environments.

Impact of cross-border travel penetration on road capacity

Based on the previous analysis of driving behavior differences, these variations have a direct impact on road capacity. Road capacity refers to the maximum number of vehicles that can traverse a roadway within a given period, typically measured in vehicles per hour. High road capacity enhances traffic flow, reduces congestion and travel time, while low capacity may result in delays, increased fuel consumption, and higher accident risks, ultimately determining the efficiency and safety of the road network. Understanding and optimizing road capacity is critical for effective traffic planning and management, especially under conditions involving mixed vehicle types. Based on the traffic flow characteristics analysis module within the methodological framework, we have constructed a macro-level fundamental diagram for mixed traffic flow. As shown in Fig. 6, on a typical three-lane road under RHT regulations, varying RHD vehicles penetration rates lead to significantly different states in the macroscopic fundamental diagram (MFD, Supplementary Fig. 7 provides an interpretation of the MFD). for each lane. Among the three lanes, the left lane exhibits the highest capacity, followed by the right lane, with the middle lane showing the lowest capacity due to frequent lane changes between the left and right lanes.

Macroscopic fundamental diagram of mixed LHD and RHD vehicle traffic flow. a illustrates the flow-density relationships for the left, middle, and right lanes under different RHD vehicle penetration rates, with colors indicating the RHD penetration of the data points. b shows the capacity of each lane and the overall road segment at various RHD penetration rates. The results reveal the impact of changing RHD penetration rates on the macroscopic fundamental diagrams of each lane and the overall capacity of the mixed traffic flow.

As the RHD vehicle penetration rate increases, overall road capacity initially declines, followed by a partial recovery. When the RHD vehicle penetration increases from 0 to 40%, capacity decreases by 14%, representing a significant drop. However, as penetration further increases from 40 to 80%, the rate of decline slows, with only a 1% reduction. Interestingly, when penetration rises from 80 to 100%, capacity increases by 5%, indicating improved system stability when RHD vehicles dominate traffic flow. This nonlinear trend highlights the complex impact of RHD vehicles’ driving behaviors on mixed traffic flow. Specifically, when RHD vehicle penetration ranges from 40 to 80%, the differences in driving behavior have the greatest impact, leading to a notable reduction in road capacity. As RHD vehicle penetration continues to rise, driving behaviors become more uniform, reducing uncertainty in lane changes and speed adjustments, and gradually restoring some of the lost capacity. This result suggests that the RHD vehicle penetration rate not only affects road usage efficiency but also has significant implications for the operational stability of mixed traffic flows.

Impact of cross-border travel penetration on traffic flow evolution

Based on the traffic flow characteristic analysis module within the methodological framework, we investigated the evolution of road capacity and mixed traffic flow states under varying RHD vehicle penetration rates, and found that they exhibit complex dynamic characteristics.

As shown in Fig. 7, changes in RHD vehicle penetration rates not only accelerated the transition of mixed traffic flow from free-flow to congested conditions but also significantly impacted overall traffic speed and its fluctuations. As the penetration rate increased, congestion onset occurred earlier; however, when the penetration rate rose from 80 to 100%, the onset of congestion was delayed, indicating a nonlinear response of traffic flow to congestion under high penetration rates as saturation approached.

Traffic state evolution in mixed LHD and RHD vehicle traffic flow. (a.i) to (a.vi) depict the spatiotemporal evolution of speed on the study road segment for RHD vehicle penetration rates of 0%, 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100%, respectively. (b) presents the average speed and the variance of average speed (\(\:{\varvec{\upalpha\:}}_{\varvec{s}\varvec{p}\varvec{e}\varvec{e}\varvec{d}}\)) across different penetration rates in mixed traffic flow. (c) illustrates congestion propagation speed under varying traffic conditions for each penetration rate.

Further analysis reveals that RHD vehicle penetration rates also had a profound effect on the average speed and speed variance within mixed traffic flow. During the transition from free-flow to congestion, average traffic speed trends mirrored those of road capacity. At a 40% penetration rate, the average speed dropped sharply by 51%. Between the 40% and 80% range, speed changes plateaued, while from 80 to 100%, overall speed increased by 7%. Notably, at an 80% penetration rate, the variance in average speed reached its lowest value, suggesting more uniform speed distribution within the mixed flow, despite lower overall speeds.

Under varying penetration rates, congestion propagation patterns in mixed traffic flow revealed complex phenomena. First, regardless of RHD vehicle penetration rate, as vehicle density increased from 30 to 90 vehicles/ln/km during congestion propagation, the speed of propagation initially rose and then declined. Second, peak congestion propagation speed varied significantly with different penetration rates. For instance, at 100% RHD vehicle penetration, maximum propagation speed reached 20 km/h as density increased from 40 to 50 vehicles/ln/km. Third, as congestion intensified, the pattern of propagation speed reversed. In the early congestion phase (density from 30 to 40 vehicles/ln/km), propagation speed increased with higher penetration rates. However, in the moderate congestion phase (density from 50 to 60 vehicles/ln/km), the speed initially decreased and then rebounded. Finally, in the severe congestion phase (density from 80 to 90 vehicles/ln/km), propagation speed steadily decreased with higher penetration rates.

These results suggest that RHD vehicle penetration rates significantly influence the dynamic characteristics and evolution of mixed traffic flow. In high-density traffic, RHD vehicle penetration affects not only road capacity but also alters the rules and speeds of congestion propagation.

Discussion

With the increasing prevalence of cross-border travel, traffic safety and operational efficiency have become focal points of global attention. Based on an in-depth study of real cross-border travel data, this study fills the research gap concerning the impact of vehicle hardware differences and sociopolitical and legal system disparities on cross-border driving, excluding the influences of language and cultural differences.

To manage cross-border travel effectively, it is essential to focus on minimizing driving behavior differences and appropriately managing the distribution of heterogeneous vehicles to ensure both traffic safety and operational efficiency. Based on these findings, we offer the following recommendations.

Our findings indicate that cross-border vehicles in mixed traffic flow indeed exhibit higher safety risks due to unfamiliarity with the traffic environment and driving rules, along with increased cautiousness. These observations align with previous studies4,9,10,11. However, unlike previous findings, we discovered that although drivers’ mental workload decreases over time19, differences in driving behavior persist in the long term. The distinct “higher highs and lower lows” speed variation observed in cross-border vehicles stems from their habitual adherence to home-country driving rules, a habit that cannot be fully corrected even after a year. A notable manifestation of this behavior is that RHD vehicles, accustomed to LHT rules, tend to drive slowly in the leftmost lane and faster in the rightmost lane. When RHD vehicles enter an RHT environment and mix with LHD vehicles that have the opposite driving habit, an interesting phenomenon emerges: LHD vehicles drive fast in the leftmost lane, while RHD vehicles drive fast in the rightmost lane. When LHD vehicles are sparse, the rightmost lane exhibits an “unobstructed phenomenon” (as LHD vehicles prefer to drive fast in the left or middle lanes, while the rightmost lane serves as a slow lane), further reinforcing RHD vehicles’ tendency to drive at high speeds in the rightmost lane. However, as LHD vehicle density increases and traffic volume rises, cautious RHD vehicles are forced to slow down. This explains why RHD vehicles tend to travel 0–29% faster than LHD vehicles in low-traffic conditions but 0–11% slower in high-traffic conditions.

Similar to mixed traffic flow studies in autonomous driving scenarios25,26,27, road capacity and traffic stability are also key metrics in this cross-border mixed traffic flow study. As the RHD penetration rate increases from 0 to 40%, road capacity significantly decreases by 13%, while traffic flow speed declines by 51%. In the 40-80% penetration range, the decline in capacity and speed stabilizes, reaching a trough at 80% penetration: road capacity decreases by 15% and speed by 53%. Interestingly, from 80 to 100%, road capacity rebounds by 5%, and speed increases by 7%. This trend of initial decline followed by recovery is also observed in mixed traffic flow studies involving autonomous and human-driven vehicles30,31,32. However, the congestion propagation pattern in cross-border mixed traffic is nonlinear across different penetration rates. As penetration increases, the onset of congestion advances, but in the 80-100% range, congestion onset is slightly delayed. Further analysis reveals that regardless of RHD penetration, congestion propagation speed initially increases and then decreases. However, the peak congestion propagation speed varies significantly across penetration rates. As congestion intensifies, propagation speed increases; yet, in moderate congestion phases, it first declines before rebounding, and in severe congestion phases, it gradually decreases as penetration increases.

Based on these findings, we propose the following recommendations for managing cross-border travel to minimize driving behavior discrepancies, regulate heterogeneous vehicle distribution, and ensure traffic safety and operational efficiency:

-

1.

Enhance the promotion and education of driving rules for cross-border travelers. For example, drivers should be reminded to adapt to new driving habits, such as driving on the right and adhering to right-turn priority rules. If necessary, a driving rule assessment could be introduced to mitigate safety risks caused by habitual differences.

-

2.

For specific road segments, especially the connecting roads linked to the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge, strengthen the regulation of the penetration rate of vehicles from Hong Kong and Macau (40%), dynamically adjusting the traffic flow entering these segments to prevent congestion.

-

3.

Establish a regular individual travel safety analysis archive, recording and analyzing the traffic violations of cross-border vehicles, and providing personalized travel management recommendations based on the analysis.

Furthermore, our findings offer new insights for vehicle research and design, emphasizing the need to address ergonomic differences across regions to accommodate diverse driving rules and road environments. This is particularly crucial as driving habits and expectations are influenced by road design, traffic regulations, and vehicle configurations. Autonomous driving technology holds significant potential to eliminate these differences through technical solutions, thereby improving cross-border travel safety and efficiency. Specifically, autonomous vehicles can adapt to varying traffic regulations via intelligent systems. For instance, when an RHD vehicle enters an LHD region, the system could automatically adjust lane selection and turning priorities, mitigating risks associated with habitual driving differences. Additionally, autonomous technology can monitor real-time road conditions and traffic flow to optimize route selection, reducing fluctuations in mixed traffic caused by driving habit discrepancies. Moreover, deep learning algorithms can accumulate driver behavior data across different traffic environments, enabling personalized driving adaptations.

These advancements will contribute to more efficient and safer cross-border travel, ensuring vehicle stability across different regulatory frameworks. Future research should further explore the role of autonomous driving technology in eliminating cross-border driving behavior disparities, particularly in the context of intelligent connected vehicles. By addressing regional ergonomic and regulatory differences, autonomous technology will not only enhance cross-border travel efficiency but also improve the stability of mixed traffic flows, laying a foundation for the intelligent and integrated development of global transportation systems.

Conclusion

This study proposes a driving behavior cognition model and a cross-border mixed traffic flow analysis framework, enhancing our understanding of driving behavior differences arising from cross-border travel and providing recommendations for cross-border traffic management. Cross-border vehicles, due to unfamiliar driving environments and opposite driving rules, tend to exhibit cautious behavior while finding it difficult to abandon their habitual adherence to previous driving rules. This results in various driving behavior differences, leading to a maximum reduction of 53% in mixed traffic flow speed and a 15% decrease in road capacity.

However, this study has certain limitations. It only focuses on the scenario where RHD vehicles mix with LHD vehicles in an RHT driving environment, without considering the scenario where LHD vehicles mix with RHD vehicles in an LHT environment. In future research, we will continue collecting trajectory data of RHD vehicles interacting with LHD vehicles in various driving environments to comprehensively investigate their mixed driving behavior differences. This will enable a deeper exploration of the relationship between driving habits and traffic rules, ultimately providing better recommendations for vehicle design, traffic operation management, and autonomous driving research.

Data availability

Data for all figures and additional data used in the analyses are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

The computer code used to generate the results reported in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Roesel, F. The causal effect of wrong-hand drive vehicles on road safety. Econ. Transp. 11–12, 15–22 (2017).

Zhang, G., Zhong, Q., Tan, Y. & Yang, Q. Risky behavior analysis for cross-border drivers: A logit model and qualitative comparative analysis of odds of fault and injury vulnerability in Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macau. J. Saf. Res. 82, 417–429 (2022).

Sivak, M., Schoettle, B., Reed, M. P. & Flannagan, M. J. Influence of visibility out of the vehicle cabin on lane-change crashes. Accid. Anal. Prev. 38, 969–972 (2006).

Bari, M. M. The study of the possibility of switching driving side in Rwanda. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 6, 439–453 (2014).

Ma, S. et al. Type 2 diabetes can undermine driving performance of middle-aged male drivers through its deterioration of perceptual and cognitive functions. Accid. Anal. Prev. 134, 105334 (2020).

Das, A., Ghasemzadeh, A. & Ahmed, M. M. Analyzing the effect of fog weather conditions on driver lane-keeping performance using the SHRP2 naturalistic driving study data. J. Saf. Res. 68, 71–80 (2019).

de la Fuente, N., Rodríguez Blanco, M., Cerdán, G., Moral, A. & Artigas, V. Leiomyosarcoma of the right gonadal vein: review of the approach and prognostic in a rare case. Case Rep. Surg. 2019, 4042689 (2019).

Wiberg, H., Nilsson, E., Lindén, P., Svanberg, B. & Poom, L. Physiological responses related to moderate mental load during car driving in field conditions. Biol. Psychol. 108, 115–125 (2015).

Dijksterhuis, C., Brookhuis, K. A. & De Waard, D. Effects of steering demand on lane keeping behaviour, self-reports, and physiology. A simulator study. Accid. Anal. Prev. 43, 1074–1081 (2011).

Cooper, P. J., Meckle, W. & Nasvadi, G. The safety of vehicles imported from right-hand-drive vehicle configuration countries when operated in a left-hand-drive vehicle environment. Accid. Anal. Prev. 41, 108–114 (2009).

Sivak, M., Schoettle, B., Reed, M. P. & Flannagan, M. J. Body-pillar vision obstructions and lane-change crashes. J. Saf. Res. 38, 557–561 (2007).

Xu, J., Guo, K., Zhang, X. & Sun, P. Z. H. Left gaze Bias between LHT and RHT: A recommendation strategy to mitigate human errors in Left- and Right-Hand driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 8, 4406–4417 (2023).

Poddar, P. & Singh, V. When left is ‘right’! The impact of driving-side practice on road fatalities in Africa. Transp. Policy. 114, 225–232 (2021).

De La Loeches, H. et al. Electrophysiological and performance variations following driving events involving an increase in mental workload. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 11, 42 (2019).

(Side) Effects of the rule of the road and neurophysiology on traffic safety: A hypothesis. Environ. Res. 183, 109246 (2020).

Wei, S., Wen, M. & Nan-Nan, Y. Dose the Difference in Driving Rules Matter for Security? in International Conference on Management Science and Engineering (ICMSE) 219–227 (2017). (2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMSE.2017.8574443

Engström, J., Markkula, G., Victor, T. & Merat, N. Effects of cognitive load on driving performance: the cognitive control hypothesis. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 59, 734–764 (2017).

Li, X., Xiao, Y., Zhao, X., Ma, X. & Wang, X. Modeling mixed traffic flows of human-driving vehicles and connected and autonomous vehicles considering human drivers’ cognitive characteristics and driving behavior interaction. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 609, 128368 (2023).

Lee, Y. C., Wen, F. & Wang, C. H. Round-trip driving effects on driving performances and mental workload under different traffic rules. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 95, 103437 (2023).

Saito, S., Murata, Y., Takayama, T. & Sato, N. An international driving simulator: recognizing the sense of a car body by the simulator. In 26th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications Workshops 254–260 https://doi.org/10.1109/WAINA.2012.161 (2012).

Wen, F. & Lee, Y. C. Driving safety assessment on standard deviation of lateral position and time exposed time-to-collision measures under driving in left-hand and right-hand traffic conventions. In Man-Machine-Environment System Engineering: Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on MMESE (eds. Long, S. & Dhillon, B. S.) 681–687 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5963-8_92 (Springer, 2022).

Nordfjærn, T., Hezaveh, A. M. & Mamdoohi, A. R. An analysis of reported driver behaviour in samples of domestic and expatriate Iranians. J. Risk Res. 18, 566–580 (2015).

Wen, H. & Xue, G. Injury severity analysis of familiar drivers and unfamiliar drivers in single-vehicle crashes on the mountainous highways. Accid. Anal. Prev. 144, 105667 (2020).

Zhu, H. B., Zhou, Y. J. & Wu, W. J. Modeling traffic flow mixed with automated vehicles considering drivers ’ character difference. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 549, 124337 (2020).

Huang, Y., Ye, Y., Sun, J. & Tian, Y. Characterizing the impact of autonomous vehicles on macroscopic fundamental diagrams. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 24, 6530–6541 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Ego-efficient lane changes of connected and automated vehicles with impacts on traffic flow. Transp. Res. Part. C Emerg. Technol. 138, 103478 (2022).

Li, Y., Zhang, S., Pan, Y., Zhou, B. & Peng, Y. Exploring the stability and capacity characteristics of mixed traffic flow with autonomous and human-driven vehicles considering aggressive driving. J. Adv. Transp. 2023, 2578690 (2023).

Liu, F., Zhao, F., Liu, Z. & Hao, H. Can autonomous vehicle reduce greenhouse gas emissions? A country-level evaluation. Energy Policy. 132, 462–473 (2019).

Hu, G., Lu, W., Whalin, R. W., Wang, F. & Kwembe, T. A. Analytical approximation for macroscopic fundamental diagram of urban corridor with mixed human and connected and autonomous traffic. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 15, 261–272 (2021).

Lu, Q., Tettamanti, T., Hörcher, D. & Varga, I. The impact of autonomous vehicles on urban traffic network capacity: an experimental analysis by microscopic traffic simulation. Transp. Lett. 12, 540–549 (2020).

Xie, D. F., Zhao, X. M. & He, Z. Heterogeneous traffic mixing regular and connected vehicles: modeling and stabilization. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 20, 2060–2071 (2019).

Zhou, J. & Zhu, F. Modeling the fundamental diagram of mixed human-driven and connected automated vehicles. Transp. Res. Part. C Emerg. Technol. 115, 102614 (2020).

Li, Y., Li, Z., Wang, H., Wang, W. & Xing, L. Evaluating the safety impact of adaptive cruise control in traffic oscillations on freeways. Accid. Anal. Prev. 104, 137–145 (2017).

Kerner, B. S. Effect of autonomous driving on traffic breakdown in mixed traffic flow: A comparison of classical ACC with three-traffic-phase-ACC (TPACC). Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 562, 125315 (2021).

Liu, H., Kan, X., Shladover, S. E., Lu, X. Y. & Ferlis, R. E. (eds) Modeling impacts of Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control on mixed traffic flow in multi-lane freeway facilities. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 95, 261–279 (2018).

Mohammed, D. & Horváth, B. Steady-Speed traffic capacity analysis for autonomous and Human-Driven vehicles. Appl. Sci. 14, 337 (2024).

Mohammed, D. & Horváth, B. Comparative analysis of following distances in different adaptive cruise control systems at steady speeds. World Electr. Veh. J. 15, 116 (2024).

Guo, M. et al. Freeway capacity modeling and analysis for traffic mixed with human-driven and connected automated vehicles considering driver behavior characteristics. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 623, 128894 (2023).

Harootunian, K., Lee, B. H. Y. & Aultman-Hall, L. Odds of fault and factors for out-of-state drivers in crashes in four States of the USA. Accid. Anal. Prev. 72, 32–43 (2014).

Yoh, K., Okamoto, T., Inoi, H. & Doi, K. Comparative study on foreign drivers’ characteristics using traffic violation and accident statistics in Japan. IATSS Res. 41, 94–105 (2017).

Nævestad, T. O., Phillips, R. O., Levlin, M., Hovi, I. B. & G. & Internationalisation in road transport of goods in Norway: safety outcomes, risk factors and policy implications. Safety 3, 22 (2017).

Alogaili, A. & Mannering, F. Unobserved heterogeneity and the effects of driver nationality on crash injury severities in Saudi Arabia. Accid. Anal. Prev. 144, 105618 (2020).

Cézard, G. et al. Ethnic variations in falls and road traffic injuries resulting in hospitalisation or death in Scotland: the Scottish health and ethnicity linkage study. Public. Health. 182, 32–38 (2020).

Zhou, Z., Du, J. & Liu, Y. Evolution, development and evaluation of eco-transportation in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao greater Bay area. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 8, 97–107 (2020).

Hong Kong and Macao vehicles traveling north. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. (2024).

Lee, J. & Jung–hyun, O. Construction of Gangzhuao-bridge and Prospects of Macao’s Economic Development. 중국학연구 221–253 (2019). https://doi.org/10.36493/JCS.87.8

Definition of Vehicles. Vehicle Types, and Routes - SUMO Documentation. https://sumo.dlr.de/docs/Definition_of_Vehicles%2C_Vehicle_Types%2C_and_Routes.html

Zhong, R. X. et al. Boundary conditions and behavior of the macroscopic fundamental diagram based network traffic dynamics: A control systems perspective. Transp. Res. Part. B Methodol. 111, 327–355 (2018).

Chen, H., Yang, C. & Xu, X. Clustering vehicle temporal and spatial travel behavior using license plate recognition data. J. Adv. Transp. 2017, e1738085 (2017).

Krau, S. Microscopic Modeling of Traffic Flow: Investigation of Collision Free Vehicle Dynamics. (1998).

Erdmann, J. SUMO’s Lane-Changing model. in Modeling Mobility With Open Data (eds Behrisch, M. & Weber, M.) 105–123 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15024-6_7. (2015).

Cui, X. Y., Song, X. F. & Zhou, C. J. Sensitivity analysis of micro-traffic simulation model parameters in woven areas. Sci. Technol. Eng. 23, 11854–11861 (2023).

Xu, D. G., Wang, Z. Q., Guo, Y. C. & Xing, K. J. A review of Whale optimization algorithm research. Comput. Appl. Res. 40, 328–336 (2023).

Leclercq, L. & Geroliminis, N. Estimating MFDs in simple networks with route choice. Transp. Res. Part. B Methodol. 57, 468–484 (2013).

Laval, J. A. & Castrillón, F. Stochastic approximations for the macroscopic fundamental diagram of urban networks. Transp. Res. Part. B Methodol. 81, 904–916 (2015).

Daganzo, C. F. A variational formulation of kinematic waves: basic theory and complex boundary conditions. Transp. Res. Part. B Methodol. 39, 187–196 (2005).

Daganzo, C. F. & Geroliminis, N. An analytical approximation for the macroscopic fundamental diagram of urban traffic. Transp. Res. Part. B Methodol. 42, 771–781 (2008).

Chang, X., Li, H., Rong, J., Zhao, X. & Li, A. Analysis on traffic stability and capacity for mixed traffic flow with platoons of intelligent connected vehicles. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 557, 124829 (2020).

Qin, Y. & Wang, H. Cell transmission model for mixed traffic flow with connected and autonomous vehicles. J. Transp. Eng. Part. Syst. 145, 04019014 (2019).

Calvert, S. C., Schakel, W. J. & van Lint, J. W. C. Will automated vehicles negatively impact traffic flow? J. Adv. Transp. 2017, 3082781 (2017).

Zheng, F., Liu, C., Liu, X., Jabari, S. E. & Lu, L. Analyzing the impact of automated vehicles on uncertainty and stability of the mixed traffic flow. Transp. Res. Part. C Emerg. Technol. 112, 203–219 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2023YFB4301900), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (No. JSGG20220831094604008), and the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (No. 2022B0101070002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.H. and Y.W. conceived the basis of the study and performed all data analyses. Z.H. and Y.W. wrote the manuscript and Supplementary Information. W.X. and C.L. assembled the experimental setup and conducted data collection. Y.W. and Z.H. supervised the study and directed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., He, Z., Xing, W. et al. Impact of regional driving behavior differences on traffic flow. Sci Rep 15, 9027 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93515-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93515-2