Abstract

This study investigated the association between handgrip strength (HGS) asymmetry and weakness with cognitive function and depressive symptoms among 920 community-dwelling adults aged above 60 years in suburban Shanghai. Participants were selected using a multistage cluster-stratified sampling approach. Assessments included HGS measured with a dynamometer, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for cognition, and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) for depressive symptoms. Restricted cubic splines revealed a positive association between dominant HGS and MoCA scores, indicating better cognitive performance, and a negative association with GDS scores, suggesting fewer depressive symptoms. The association between the HGS ratio and MoCA scores and the HGS ratio and GDS scores varied by sex. Women with HGS weakness alone (odds ratio (OR) = 2.00, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.17–3.37), asymmetry alone (OR = 1.93, 95% CI = 1.14–3.29), or weakness and asymmetry together (OR = 2.57, 95% CI = 1.48–4.46) had a significantly increased risk of cognitive impairment. However, no such associations observed in men. These findings suggest that HGS weakness and asymmetrical HGS may be associated with a higher risk of cognitive decline and depressive symptoms, particularly in women. This study emphasizes the need for sex-specific assessments and prevention strategies to address cognitive and mental health issues among older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The aging of the global population amplifies the significance of health issues among older adults, including cognitive decline, depression, frailty, coronary heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, sarcopenia, multimorbidity, and other conditions1,2,3,4,5. Studies have shown that the prevalence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and depressive symptoms among older adults in China has reached 15.5%6and 20.0%7, respectively. Cognitive disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease and MCI, as well as affective disorders like depression, significantly impact older adults’ self-sufficiency and social engagement8,9. The substantial burden these conditions place on families and healthcare systems underscores their importance as key areas of public health research.

Recent research highlights the close association between cognitive disorders, depression, and physiological decline in older adults, including reduced muscle mass, decreased muscle strength, and slower gait10,11,12. Although gait speed and muscle mass assessments are valuable, they may be limited by individual lower limb mobility and healthcare facility capabilities13,14. Handgrip strength (HGS) offers a stable, convenient, and cost-effective method for assessing muscle strength and has become a focus of increasing research15.

Despite the growing interest in the association between HGS and cognitive and depressive status, a notable concern is the variety of HGS measurement methodologies across studies, particularly the neglect of asymmetry between the dominant and non-dominant hands16. Measuring HGS asymmetry provides critical information for a more refined understanding of muscle strength and asymmetry. This study aimed to address these gaps and explore the associations between dominant HGS, HGS asymmetry, and cognitive and depressive status.

Methods

Study population

This study, using a multistage cluster-stratified sampling method, focused on community-dwelling older adults aged 60–90 years living in suburban Shanghai with no history of psychotic disorders or limited mobility in 2019. The specific sampling method can be found in the previous study17. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shanghai University of Medicine & Health Sciences (2019-SMHC-01–003) and was conducted strictly in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All research activities adhered to the ethical standards, including obtaining written informed consent from participants prior to data collection.

Measurements

HGS assessment.

HGS was assessed using a mechanical dynamometer as part of a comprehensive medical examination. Participants were instructed to position their elbows at a 90-degree angle and apply maximal force to the dynamometer for several seconds, alternating between both hands. The dominant and non-dominant hands were identified based on comparative HGS measurements, with the hand exhibiting the greatest force designated as the dominant hand. According to the 2019 Asian Sarcopenia Consensus, HGS weakness is classified as an HGS of less than 28 kg in men and less than 18 kg in women18. The HGS ratio was calculated by dividing the dominant HGS by the non-dominant HGS (dominant HGS, kg/non-dominant HGS, kg). Participants exhibiting a ratio of 1.00–1.10 were characterized as having HGS symmetry, whereas those with a ratio > 1.10 were identified as having HGS asymmetry. The participants were classified into four HGS status groups: neither weakness nor asymmetry, weakness alone, asymmetry alone, and weakness and asymmetry together.

Clinical assessment.

Cognitive function was evaluated using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) with a 30-point scale1920. This scale effectively categorizes our study population into two distinct groups based on scores. The cut-off scores varied depending on education level: 13 for illiterate, 19 for primary school graduates, and 24 for middle school or higher21. Individuals scoring above these cut-off values are considered to have normal cognitive function, while those scoring below are classified as having cognitive impairment. The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) comprises 30 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 30; scores 10 or above are categorized as indicative of depression, while below 10 are considered normal22. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) includes general, anthropometric, dietary, and subjective assessments23. The scale was calibrated using reference values ranging from 0 to 30. All the assessment scales mentioned above are Chinese versions.

Covariates assessment.

The following socio-demographic covariates were included: sex, age, education level (“illiteracy,” “primary school,” “junior high school or higher.”), pre-retirement occupation (“non-manual,” “manual,” and “mixed.”), living arrangement (“living alone,” and “not living alone.”), and income (“less than ¥1000 per month,” “¥1000–¥3000 per month,” “¥3000–¥5000 per month,” and “more than ¥5000 per month.”). These factors were assessed through face-to-face interviews using standardized questionnaires. Data on biological characteristics such as body mass index (BMI) were collected during medical checkups.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), and categorical variables are expressed as percentages. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square tests were used to evaluate differences in baseline sociodemographic, lifestyle, and health characteristics.

Linear regression models with restricted cubic splines (RCS) were fitted to assess nonlinearity among dominant HGS, HGS ratio, MoCA score, and GDS score. The optimal number of knots was determined based on the Akaike Information Criterion, Bayesian Information Criterion, and changes in the R² values of the model. It was found that the RCS with three knots was adequate for capturing nonlinear patterns in the data without overfitting.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between the HGS status and cognitive impairment and depression. The covariates adjusted in the RCS and multivariate logistic regression models included age, BMI, living arrangements, education level, pre-retirement occupation, MNA score, and income. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R (version 4.3.3, https://www.R-project.org/). Tests were two-tailed, with a significance level of P < 0.05.

Results

After excluding individuals with incomplete data, a total of 920 individuals aged over 60 years were included in our study (men: 42.3%; women: 57.7%). The participants were divided into the following age groups: 60–69 years (370 participants), 70–79 years (450 participants), and 80–89 years (100 participants). The range of age, MoCA, GDS, dominant HGS, non-dominant HGS, and HGS ratio were 60–89 years, 2–30, 0–29, 5.10–44.90 kg, 4.80–43.40 kg, 1.00–1.30, respectively. The median (IQR) age, MoCA, GDS, dominant HGS, non-dominant HGS, and HGS ratio were 71 (66–75) years, 19 (15–23), 5 (2–8), 22.65 (17.73–29.48) kg, 21.00 (16.10–27.60) kg, and 1.07 (1.03–1.12), respectively.

ANOVA demonstrated that MoCA scores, dominant HGS, and non-dominant HGS declined with increasing age (all P < 0.001), lower education levels (all P < 0.001), and in individuals living alone (all P < 0.01). GDS scores were higher in lower-income groups (P = 0.004) and individuals living alone (P < 0.001). The HGS ratio was higher in groups with lower education level (P < 0.001) and those living alone (P = 0.010). Sex was a significant factor influencing the results of all five assessments (all P < 0.01), with women showing adverse outcomes (Table 1).

RCS analysis demonstrated positive associations between dominant HGS and MoCA scores in both men and women, with the association plateauing at 32 kg in men (Fig. 1A1 and 1A2). A negative association between dominant HGS and GDS scores was observed in both groups, with the association flattening after 30 kg in men and 20 kg in women (Fig. 1B1 and 1B2). However, no statistically significant nonlinear patterns were observed (all P for nonlinearity > 0.05).

We also analyzed the associations between the HGS ratio, MoCA scores, and GDS scores (Fig. 2). The RCS graph for men displayed a slight increase followed by a decrease in MoCA scores (P for nonlinearity = 0.161) (Fig. 2A1). In contrast, women demonstrated a significant L-shaped association, with the lowest MoCA scores at an HGS ratio of approximately 1.1 (P for nonlinearity = 0.022) (Fig. 2A2). Regarding GDS scores, men showed a trend where scores initially decreased and then increased, with the lowest point at an HGS ratio of approximately 1.1 (Fig. 2B1). Conversely, women displayed a positive association between the HGS ratio and GDS scores (Fig. 2B2). However, the nonlinear associations with GDS scores were not statistically significant for either sex (P for nonlinearity = 0.125 for men, P for nonlinearity = 0.846 for women).

Associations of Dominant HGS with MoCA And GDS Scores. (A1) Association of Dominant HGS with MoCA Scores in Men. (A2) Association of Dominant HGS with MoCA Scores in Women. (B1) Association of Dominant HGS with GDS Scores in Men. (B2) Association of Dominant HGS with GDS Scores in Women. All adjusted for age, BMI, living arrangement, education levels, pre-retirement occupation, MNA scores, income. HGS: handgrip strength; MoCA: the Montreal Cognitive Assessment; GDS: the Geriatric Depression Scale; BMI: Body mass index; MNA: the Mini Nutritional Assessment.

Associations of HGS Ratio with MoCA And GDS Scores. (A1) Association of HGS Ratio with MoCA Scores in Men. (A2) Association of HGS Ratio with MoCA Scores in Women. (B1) Association of HGS Ratio with GDS Scores in Men. (B2) Association of HGS Ratio with GDS Scores in Women. All adjusted for age, BMI, living arrangement, education levels, pre-retirement occupation, MNA scores, income. HGS ratio: handgrip strength ratio; MoCA: the Montreal Cognitive Assessment; GDS: the Geriatric Depression Scale; BMI: Body mass index; MNA: the Mini Nutritional Assessment.

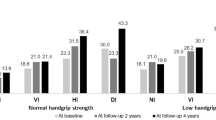

In men, the prevalence of the four HGS status groups was 47.6% with neither weakness nor asymmetry, 25.4% with weakness alone, 15.2% with asymmetry alone, and 11.8% with weakness and asymmetry. The corresponding prevalence rates in women were 37.8%, 22.4%, 20.3%, and 19.4%, respectively. Participants in groups with HGS weakness alone, asymmetry alone, or weakness and asymmetry together, compared with those with neither weakness nor asymmetry, exhibited statistically significant characteristics in both sexes, including higher mean age, GDS, and MNA scores, lower dominant and non-dominant HGS values, and lower mean MoCA score (Table 2).

After converting continuous MoCA and GDS scores into categorical cognitive impairment and depression variables, we conducted a multiple logistic regression analysis. The results revealed that HGS weakness alone, HGS asymmetry alone, and weakness and asymmetry together were all significantly associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment in women (weakness alone: OR = 2.00, 95% CI = 1.17–3.37; asymmetry alone: OR = 1.93, 95% CI = 1.14–3.29; together: OR = 2.57, 95% CI = 1.48–4.46). However, no significant association was found between HGS and cognitive impairment in men. Additionally, no significant association was observed between HGS status and depression in the overall population of either sex (Table 3).

Discussion

The correlation between HGS and the significant physiological and psychological changes in older adults is of growing interest to researchers. Our cross-sectional study indicates that higher dominant HGS and greater symmetry in HGS are linked to enhanced cognitive function and reduced depressive symptoms, particularly among women.

Our findings align with previous studies regarding the positive correlation between dominant HGS and MoCA scores24,25,26. Longitudinal studies have also revealed that individuals with weak HGS are at an increased risk of developing MCI or dementia27,28,29. Likewise, our results concerning the negative association between dominant HGS and GDS scores are consistent with other studies30,31. One potential mechanism for these associations could be regular physical activity, which not only maintains HGS but also stimulates the growth of prefrontal and hippocampal brain regions, potentially reducing cognitive decline and depression32,33,34,35,36. Another proposed explanation involves oxidative stress and inflammation, which are linked to cognitive performance, depression, and muscle mass, possibly mediating their association37,38,39,40,41. Our RCS models highlighted plateaus in the associations between dominant HGS and MoCA and GDS scores, indicating a threshold below which further decreases in dominant HGS significantly affect cognitive and depressive outcomes. This finding suggests that maintaining HGS above this threshold may be crucial for preventing cognitive decline and depression in older adults. These thresholds correspond to established cutoff points for HGS weakness, emphasizing the clinical relevance of these findings18.

Our analysis revealed that increased HGS asymmetry was associated with poorer cognitive performance and heightened depressive symptoms. While relevant studies are limited, some results support our findings42,43. One possible explanation is that HGS asymmetry may indicate an imbalance in hippocampal or frontal lobe volumes44or neural function45. The RCS models demonstrated associations between the HGS ratio, cognitive function, and depression. Critical inflection points differed between sexes, suggesting that women are more susceptible to the effects of HGS asymmetry. Additionally, women with HGS weakness alone, HGS asymmetry alone, or both exhibited a higher risk of cognitive impairment than those without these conditions, a pattern not observed in men. This effect is supported by a Japanese study that found a more pronounced link between skeletal muscle health and cognitive function in women46. Recent longitudinal studies have demonstrated that low HGS in women shows stronger predictive value for subsequent Activities of Daily Living (ADL) disability compared to men47,48. However, our study did not include an analysis related to ADL. The biological basis of these sex differences has not been fully elucidated but may involve factors such as the smaller gray matter volume in women49, making them more prone to rapid declines in gray matter volume associated with aging and uneven losses in brain regions linked to neurodegenerative diseases5051. Additionally, sex hormones have been proposed as contributing factors52. These insights underscore the critical need to consider sex-specific risk factors when assessing and preventing cognitive decline and depression.

This study has several strengths. Firstly, it explored both separate and combined associations of HGS asymmetry and weakness with the risk of cognitive impairment and depression in older adults, providing comprehensive insights into these associations. Secondly, sex-stratified analyses were conducted to explore the potential effect of sex on the associations between HGS, cognition, and depression. Additionally, the utilization of standardized and widely recognized assessment tools, such as the MoCA and GDS, enhances the reliability and validity of the findings, facilitating direct comparisons with other studies. However, several limitations should be noted. Firstly, the cross-sectional design of the study limited the ability to infer causality between HGS status, cognitive decline, and depressive symptoms. Secondly, the generalizability of the study may be constrained by the restricted sample size and the exclusion of certain participants, particularly men. Thirdly, the absence of comprehensive ADL assessments precludes analysis of whether functional independence mediates the observed associations between HGS and cognitive function. Furthermore, information regarding hand dominance was absent in our study. Consequently, the hand with the highest HGS was designated as the dominant hand, potentially resulting in our handgrip ratio starting at 1.0 without variation below it, which differs from other studies where the handgrip ratio was distributed around 1.0, encompassing values both above and below. Nevertheless, a definition similar to ours has been used in some studies53. Additionally, there was a significant amount of missing data regarding comorbid conditions such as hypertension, stroke, and diabetes in our study, which limits our ability to conduct a more in-depth analysis54.

Conclusion

These findings highlight the importance of jointly evaluating the strength and symmetry of HGS in relation to cognitive impairment and depression, particularly among women. Future investigations should delve deeper into the causal association between HGS status and adverse health outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Thillainadesan, J., Scott, I. A. & Le Couteur, D. G. Frailty, a multisystem ageing syndrome. Age Ageing. 49, 758–763 (2020).

Yarnall, A. J. et al. New horizons in Multimorbidity in older adults. Age Ageing. 46, 882–888 (2017).

Calvani, R. et al. Biomarkers for physical frailty and sarcopenia. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 29, 29–34 (2017).

Blazer, D. G. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 58, 249–265 (2003).

Culig, L., Chu, X. & Bohr, V. A. Neurogenesis in aging and age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 78, 101636 (2022).

Jia, L. et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in adults aged 60 years or older in China: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Public. Health. 5, e661–e671 (2020).

Tang, T., Jiang, J. & Tang, X. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among older adults in Mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 293, 379–390 (2021).

Global status report on the public health. response to dementia. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240033245

Partridge, L., Deelen, J. & Slagboom, P. E. Facing up to the global challenges of ageing. Nature. 561, 45–56 (2018).

Bullain, S. S. et al. Poor physical performance and dementia in the oldest old: the 90 + study. JAMA Neurol. 70, 107–113 (2013).

Montero-Odasso, M. et al. Motor and cognitive trajectories before dementia: results from gait and brain study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 66, 1676–1683 (2018).

Beeri, M. S., Leugrans, S. E., Delbono, O., Bennett, D. A. & Buchman, A. S. Sarcopenia is associated with incident Alzheimer’s dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and cognitive decline. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 69, 1826–1835 (2021).

Ticinesi, A., Meschi, T., Narici, M. V., Lauretani, F. & Maggio, M. Muscle ultrasound and sarcopenia in older individuals: A clinical perspective. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 18, 290–300 (2017).

Schwenk, M., Schmidt, M., Pfisterer, M., Oster, P. & Hauer, K. Rollator use adversely impacts on assessment of gait and mobility during geriatric rehabilitation. J. Rehabil Med. 43, 424–429 (2011).

Wang, D. X. M., Yao, J., Zirek, Y., Reijnierse, E. M. & Maier, A. B. Muscle mass, strength, and physical performance predicting activities of daily living: a meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 11, 3–25 (2020).

Chen, X. et al. Effects of measurement protocols and repetitions on handgrip strength weakness and asymmetry in patients with cancer. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 15, 220–230 (2024).

Zhang, P. et al. Sociodemographic features associated with the MoCA, SPPB, and GDS scores in a community-dwelling elderly population. BMC Geriatr. 23, 557 (2023).

Chen, L. K. et al. Asian working group for sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21, 300–307e2 (2020).

Jia, X. et al. A comparison of the Mini-Mental state examination (MMSE) with the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) for mild cognitive impairment screening in Chinese middle-aged and older population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 21, 485 (2021).

Pinto, T. C. C. et al. Is the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) screening superior to the Mini-Mental state examination (MMSE) in the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in the elderly? Int. Psychogeriatr. 31, 491–504 (2019).

Lu, J. et al. Montreal cognitive assessment in detecting cognitive impairment in Chinese elderly individuals: a population-based study. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 24, 184–190 (2011).

Smarr, K. L. & Keefer, A. L. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: Beck depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D), geriatric depression scale (GDS), hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), and patient health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Arthritis Care Res. 63 (Suppl 11), S454–466 (2011).

Vellas, B. et al. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) and its use in grading the nutritional state of elderly patients. Nutrition. 15(2) (1999)

Jiang, R. et al. Associations between grip strength, brain structure, and mental health in > 40,000 participants from the UK biobank. BMC Med. 20, 286 (2022).

Jang, J. Y. & Kim, J. Association between handgrip strength and cognitive impairment in elderly Koreans: a population-based cross-sectional study. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 27, 3911–3915 (2015).

Sui, S. X. et al. Associations between muscle quality and cognitive function in older men: Cross-Sectional data from the Geelong osteoporosis study. J. Clin. Densitom Off J. Int. Soc. Clin. Densitom. 25, 133–140 (2022).

Chou, M. Y. et al. Role of gait speed and grip strength in predicting 10-year cognitive decline among community-dwelling older people. BMC Geriatr. 19, 186 (2019).

Alfaro-Acha, A. et al. Handgrip strength and cognitive decline in older Mexican Americans. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 61, 859–865 (2006).

Jeong, S. M. et al. Association among handgrip strength, body mass index and decline in cognitive function among the elderly women. BMC Geriatr. 18, 225 (2018).

Gu, Y. et al. Grip strength and depressive symptoms in a large-scale adult population: the TCLSIH cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 279, 222–228 (2021).

G, A. F. et al. Handgrip strength and depression among 34,129 adults aged 50 years and older in six low- and middle-income countries. J. Affect. Disord 243, (2019).

Erickson, K. I. et al. Physical activity predicts Gray matter volume in late adulthood: the cardiovascular health study. Neurology 75, 1415–1422 (2010).

Legdeur, Nienke et al. What Determines Cognitive Functioning in the Oldest-Old? The EMIF-AD 90+ Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 76, 1499–1511 (2021).

Gujral, S., Aizenstein, H., Reynolds, C. F. & Butters, M. A. Erickson, K. I. Exercise effects on depression: possible neural mechanisms. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 49, 2–10 (2017).

Jung, Y. H. et al. Frontal-executive dysfunction affects dementia conversion in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Sci. Rep. 10, 772 (2020).

Lee, H. S. et al. Frontal dysfunction underlies depression in mild cognitive impairment: A FDG-PET study. Psychiatry Investig. 7, 208–214 (2010).

Weaver, J. D. et al. Interleukin-6 and risk of cognitive decline: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Neurology 59, 371–378 (2002).

Pedersen, B. K. & Febbraio, M. A. Muscle as an endocrine organ: focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiol. Rev. 88, 1379–1406 (2008).

Liu, J. J. et al. Peripheral cytokine levels and response to antidepressant treatment in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry. 25, 339–350 (2020).

Soysal, P. et al. Relationship between depression and frailty in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 36, 78–87 (2017).

Jiang, R. et al. The brain structure, inflammatory, and genetic mechanisms mediate the association between physical frailty and depression. Nat. Commun. 15, 4411 (2024).

Peng, T. C., Chiou, J. M., Chen, Y. C. & Chen, J. H. Handgrip strength asymmetry and cognitive impairment risk: insights from a seven-year prospective cohort study. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 28, 100004 (2024).

Hurh, K., Park, Y., Kim, G. R., Jang, S. I. & Park, E. C. Associations of handgrip strength and handgrip strength asymmetry with depression in the elderly in Korea: A Cross-sectional study. J. Prev. Med. Public. Health Yebang Uihakhoe Chi. 54, 63–72 (2021).

Meysami, S. et al. Handgrip strength is related to hippocampal and Lobar brain volumes in a cohort of cognitively impaired older adults with confirmed amyloid burden. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD. 91, 999–1006 (2023).

Carson, R. G. Get a grip: individual variations in grip strength are a marker of brain health. Neurobiol. Aging. 71, 189–222 (2018).

McGrath, R., Cawthon, P. M., Cesari, M., Al Snih, S. & Clark, B. C. Handgrip strength asymmetry and weakness are associated with lower cognitive function: A panel study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 68, 2051–2058 (2020).

Dai, S., Wang, S., Jiang, S., Wang, D. & Dai, C. Bidirectional association between handgrip strength and ADLs disability: a prospective cohort study. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1200821 (2023).

Muhammad, T., Hossain, B., Das, A. & Rashid, M. Relationship between handgrip strength and self-reported functional difficulties among older Indian adults: the role of self-rated health. Exp. Gerontol. 165, 111833 (2022).

Gennatas, E. D. et al. Age-Related effects and sex differences in Gray matter density, volume, mass, and cortical thickness from childhood to young adulthood. J. Neurosci. 37, 5065–5073 (2017).

Driscoll, I. et al. Longitudinal pattern of regional brain volume change differentiates normal aging from MCI. Neurology. 72, 1906–1913 (2009).

Tian, Q., Osawa, Y., Resnick, S. M., Ferrucci, L. & Studenski, S. A. Rate of muscle contraction is associated with cognition in women, not in men. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 74, 714–719 (2019).

Genazzani, A. R., Pluchino, N., Luisi, S. & Luisi, M. Estrogen, cognition and female ageing. Hum. Reprod. Update. 13, 175–187 (2007).

Mahoney, S. J. et al. Handgrip strength asymmetry is associated with limitations in individual basic Self-Care tasks. J. Appl. Gerontol. Off J. South. Gerontol. Soc. 41, 450–454 (2022).

Klawitter, L. et al. Handgrip strength asymmetry and weakness are associated with future morbidity accumulation in Americans. J. Strength. Cond Res. 36, 106–112 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to all the staff involved in the study and the most tremendous respect to the participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.Z and J.D was responsible for project administration. D.F.W and Y.P.S worked on data cleaning and curation. M.L and Y.Y.M work on interpretation of results. N.A worked on the data analyses, wrote the first draft of the manuscript. N.A and P.Z were mainly responsible for the revisions during the manuscript revision process. Q.X.Z was responsible for supervision of this study and improvement of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (grant number 19ZR1444600) and Shanghai Municipal Health Commission clinical research foundation (grant number 202040277).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abudukelimu, N., Zhang, P., Du, J. et al. Association of handgrip strength weakness and asymmetry with cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms in older Chinese adults. Sci Rep 15, 9763 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93573-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93573-6