Abstract

Minor ischemic stroke (MIS) patients face significant risks of recurrent strokes, necessitating reliable predictive tools. This single-center retrospective study developed and validated a novel model for predicting 1-year stroke recurrence in MIS patients, defined as those with National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale scores < 4 within seven days of symptom onset. Among 218 patients (median age 64 years, 26.6% female), 32 (14.7%) experienced recurrent strokes within one year. Analysis of clinical and lifestyle variables identified physical activity, large artery stroke, admission NIHSS score, and smoking as significant predictors, forming the PLANS model. The model demonstrated superior predictive performance compared to the Essen model, with a higher C-index (0.780 vs. 0.556) and better calibration. Risk reclassification metrics showed significant improvements, with integrated discrimination improvement of 20.3%, continuous net reclassification improvement of 41.7%, and median risk score improvement of 18.5%. The PLANS model, incorporating both traditional and novel risk factors, provides a valuable tool for patient stratification and personalized secondary prevention strategies. External validation in diverse cohorts is warranted to confirm these promising results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Minor ischemic strokes (MIS) with low National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores is major health challenge with approximately 1 million new cases annually in China1. Patients with MIS account for about 50% of all cases of ischemic strokes2, and are at high risk of recurrence, leading to increased disability and mortality3. Recurrent cerebrovascular events are primarily associated with three types of risk factors: 1) nonmodifiable factors such as family history, sex, and age; 2) medically modifiable factors including medical treatments and non-medical interventions; and 3) behaviorally modifiable factors such as physical inactivity and smoking4. Targeting modifiable risk factors, such as adopting a healthy lifestyle, is known to be important for preventing recurrent strokes (RS). It is, however, unknown if lifestyle interventions are associated with a significant reduction in the risk of MIS recurrence. It is also important to define the most effective lifestyle intervention for prevention of MIS recurrence.

It is crucial to identify the risk factors that are closely associated with RS in patients with MIS. Previous studies have primarily focused on early detection and short-term risk assessment, with limited data available on 1-year clinical outcomes5. Additionally, the risk factors for recurrence of MIS may vary widely in the individuals with MIS. Several methods have been used to estimate the risk of ischemic strokes6. Like MIS, transient ischemic attack (TIA) is subject to a high rate of recurrence. There are methods to predict the risk of RS in TIA patients, such as scores ABCD2 or ABCD37,8. The Stroke Prognosis Instrument II or the Essen Stroke Risk Score have been used to estimate the risk for recurrent ischemic stroke9,10. However, these predictive models do not account for the unique characteristics of MIS and are unable to differentiate between major and minor strokes, and mostly, don’t provide accurate predictive values on RS for patients with minor strokes11. Thus, improved prediction models that specifically address the risk of RS in MIS are needed for accurate risk assessment and effective secondary preventive strategies.

Recent evidence from landmark trials such as CHANCE, POINT, and THALES, as well as real-world studies12,13, has shown that early short-term dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) significantly reduces stroke recurrence rates in minor ischemic stroke (MIS) patients. While current guidelines recommend DAPT for preventing recurrent strokes, irrespective of recurrence risk, the PLANS model provides a valuable tool to refine decision-making by identifying high-risk patients who are most likely to benefit from DAPT. These patients may be prioritized for more intensive treatment, while those at lower risk may not require such aggressive interventions. Future studies should explore the integration of the PLANS model with the latest DAPT protocols to enhance secondary stroke prevention strategies.

The present study was designed to develop a novel predictive model for the risk of 1-year recurrence of MIS. There were two specific aims: 1) to identify the individualized factors significantly associated with the risk of 1-year stroke recurrence in MIS patients; 2) to construct and validate a novel model to predict the 1-year RS risk for MIS patients, using the significant variables. This study aims to provide a more nuanced understanding of the risk factors associated with MIS recurrence and to refine current preventive strategies by emphasizing individualized approaches for reducing RS risk.

Methods

Study groups

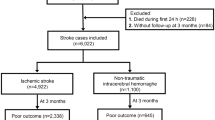

The present study constitutes a secondary analysis of a prospectively collected database from a single institution in southeast China, encompassing patients diagnosed with their first instance of acute ischemic stroke between November 2012 and January 2014. The inclusion criteria for the present study were 18 or older and first symptomatic MIS with a score of 3 or less on the NIHSS (higher scores indicate more severe symptoms, ranging from 0 to 42) in the first seven days after the onset of symptoms. An NIHSS score of 3 or less is considered a MIS.14 Patients were excluded for the study if any of the following conditions were present: prior carotid stent placement, carotid endarterectomy, significant cardiopulmonary disease, renal dysfunction, liver disease, malignancy, and significant mental disease or dementia. The patient enrollment and data analysis protocols were detailed in Fig. 1.

Indicator determination

Baseline information was collected within 24 h of admission, including past medical history, demographic information, post-admission assessment, and laboratory and imaging data. According to the Org10172 Clinical Trials for the Treatment of Acute Stroke (TOAST) criteria15, patients were divided into those with large artery atherosclerosis (LAA) ischemic stroke (IS) and non-LAA IS. Stroke etiology was determined by certified neurologists using a combination of clinical data and neuroimaging findings, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT), to confirm ischemic infarcts, exclude hemorrhagic strokes, and identify specific infarct locations. Based on the vessels involved, acute ischemic stroke (AIS) was further subdivided into total posterior, total anterior, partial anterior and posterior AIS. In body mass index (BMI) calculations, weight (kilograms) was divided by height (meters) squared. Education was classified, using the highest level of completed education, as illiterate, primary, secondary (middle and high school), and college or above. Risk factors evaluated in this study comprised smoking status (defined as current smoking or smoking cessation within the past 12 months), regular physical activity (characterized as performing housework or engaging in exercise for a minimum of 30 min daily), and admission NIHSS scores for stroke severity assessment. These operational definitions were consistent with our previous research criteria16.

Data on lifestyle of the enrolled subjects was obtained one year after the first IS, including diet, activity, sleep status, and living condition. A bland diet was defined as a light diet without being greasy, spicy, salty, or sweet. Daily fresh fruit use referred to daily consumption of unprocessed fresh fruits. Physical activity (PA) was defined as 30 min or more aerobic exercise at least twice a week. Household activities were defined as participating in any daily household activities for at least 3 h a day on most days of the week, including (but not limited to) laundry, cleaning, shopping, cooking, dish washing, and caregiving. Sleep quality was considered good if the patient slept comfortably for 7–9 h at night without any of the following while asleep: trouble falling in or staying in asleep, waking up in the middle of sleep and unable to go back to sleep, frequent leg movements during sleep, snoring, or sleep apnea.

Outcome

The primary outcome was a second stroke (hemorrhagic or ischemic) within one year. At 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after the first ischemic stroke, a certified specialist on the research team called the patients to collect information on possible RS and medications. Essen Stroke Risk Score (ESRS) was calculated independently by a trained researcher (YL) who was blinded to patient outcomes to minimize potential bias in risk factor evaluation.

Statistical analysis

Data for continuous variables were represented as means ± standard deviation (SD) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs), and Categorical variables were represented as percentages. Analyses were performed using the R Statistical software (version 4.2.1; R Core Team, 2022) on macOS Ventura 13.2.1. First, univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazards (Cox regression) models were used to determine the effects of individual variables on RS using univariable analysis. Significant variables (P < 0.05) in the Cox regression analysis were used to construct a 1-year prognosis prediction model for the patients with minor stroke. The Kaplan–Meier (KM) method was used to demonstrate the effect of the significant variables on RS. Next, to validate the prediction model (bootstrapping with 1000 replicates) and to compare its predictive value with the traditional ESSEN model, the predictive accuracy was assessed by calibration of the estimated models, while the discrimination was defined by the Concordance Index (C-index), and the clinical values were estimated by decision curve analysis (DCA). The mean predicted risk was compared against the observed frequency of events in the cohort for individual variables. An evaluation of discrimination is based on how well a model separates subjects with and without an event. A C-index estimates the discrimination from no better than chance (0.5) to perfect (1.0). In the case of two subjects, one with and the other without the event of interest, the C-index indicates the likelihood that the subject with the event has a higher predicted risk than one without. In addition, we calculated the integrated discrimination improvement (IDI)17, another measure of discrimination. IDI estimates the improvement in discrimination achieved by the new model over the reference model. Finally, a nomogram was created with the R software using the “rms” library to reveal the prediction model. A 2-sided p value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. We followed TRIPOD (Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis) guidelines for reporting prediction model studies18.

Power calculations

In this study, samples were not calculated in advance because the data set was fixed size. Instead, a range of hazard ratios and group proportions was used to calculate study power. Given the 218 known ischemic stroke events and 15% of subjects in uncensored events (RS), the hazard ratio (HR) of 3.10 between the groups could be detected with 89.9% power using a Cox proportional hazards regression model with an error rate of 0.05. The study was likely adequately powered, with study power ranging from 78.0% (HR, 2.60) to 99.9% (HR, 0.17). Power calculations were performed using the survivalpwr package in R19.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 218 patients with MIS were included in the present study: 32 patients with RS and 186 subjects without RS. The baseline patient characteristics were shown in Table 1. Compared with the patients without RS, patients with RS had more severe neurological deficits as estimated with NIHSS score on admission (P = 0.001) and a higher rate of smoking (P = 0.005). In addition, there was a significant increase in the recurrence of stroke in patients with LAA stroke as compared with non-LAA IS (P < 0.001). On the other hand, PA (P = 0.016) and fruit intake (P = 0.045) were significantly less in the patients with RS than that in the ones without RS.

Independent high-risk factors associated with the RS

All variables in Table 1 were initially analyzed with univariate Cox regression analysis. Then, the statistically significant variables identified in the univariate analysis were further analyzed using multivariable models. Multivariate Cox analysis showed that lack of PA (P) (HR = 0.248, 95% CI 0.106–0.584 for housework or exercise vs no PA; HR = 0.170, 95% CI 0.070–0.411 for housework plus exercise vs no PA), LAA stroke (LA) (HR = 2.603, 95% CI 1.189–5.701), admission NIHSS score (N) (HR = 3.092, 95% CI 1.781–5.368), and smoking (S) (HR = 2.793, 95% CI 1.359–5.741) were independent risk factors associated with increased risk for RS (Fig. 2 and Table S1).

Construction and validation of PLANS

Based on the significant variables, a model that included PA (housework or exercise), LAA stroke, admission NIHSS score, and smoking (PLANS) was created. In the internal validation cohort, the C-index for the PLANS model was significantly higher (0.780; 95% CI, 0.760–0.800) than that for the ones using Essen scores (0.556; 95% CI, 0.532–0.580) (Fig. 3). The Calibration curves also showed a better agreement between the predicted values and the observed ones for the risk of RS in the PLANS model than that in the Essen model (Fig. 4A). The IDI, continuous-NRI, and median improvement in risk score also favored the 4-variable PLANS model compared with the Essen model. For example, significantly improved classification of the risk categories was observed with the PLANS model compared with the Essen model (IDI = 20.3%, continuous-NRI = 41.7%, and median improvement = 18.5%, respectively; all P-values < 0.05) (Fig. 4B).

Deep learning evaluation PLANS model. A. 1-year calibration curves of the two RS model in the internal validation set. B. IDI curve, in which the new model refers to the Essen model. M1 (green area): Result of IDI. M2 (distance between black points): Result of continuous-NRI. M3 (distance between gray points): Result of median improvement in risk score. NRI, net reclassification improvement; IDI, integrated discrimination improvement. C. DCA curves. The DCA curve of the new model is compared with that of the Essen model in the internal validation set. DCA, decision curve analysis. D. The dynamic nomogram of PLANS. By entering each variable on the left and clicking “Predict”, the graphical summary for a patient is automatically calculated.

Clinical application of PLANS

The clinical applicability of the PLANS model was assessed through DCA based on threshold probabilities and net benefits. As shown by the DCA in the internal validation cohort, our risk prediction model had a favorable net benefit with a wide range of threshold probabilities, but while the Essen model didn’t (Fig. 4C).

An online nomogram for risk prediction

Based on a multivariate Cox regression analysis, the following independent predictors for RS were identified: PA (housework or exercise), LAA stroke, admission NIHSS score, and smoking. To facilitate the clinical use of the PLANS model, an easy-to-use online nomogram using a “DynNom” package of the R software was generated on shinyapps.io. The online nomogram could be accessed at this URL: https://ody-wong.shinyapps.io/PLANS/. By entering the prediction variables, the online nomogram could provide instant values on survival probabilities, as well as individualized displays in figures, tables, and graphs. Anyone including the public can use it any time freely without any restrictions (Fig. 4D).

Discussion

Main findings

The present study for the first time demonstrated that a combination of 4 specific factors (PA, LAA stroke, admission NIHSS score, and the status of smoking) could predict the risk of RS at 1 year in patients with acute MIS. Based on the value of each variable, a new PLANS algorithm has been developed to predict the risk of RS in patients with MIS.

Clinical implications

Global Burden of Disease Study has revealed that the lifetime stroke risk and disease burden are very high20. Ischemic strokes account for 85% of all strokes21, while minor strokes make up 40% of ischemic strokes22. Because the symptoms for minor strokes are usually transient and subtle clinically, patients tend to overlook them. However, the one-year all-cause mortality and composite cardiovascular events were 6.2% and 1.8%, respectively, and the rates for the subsequent five years were 12.9% and 10.6%, respectively23,24. In addition, recurrent strokes can result in severe and difficult-to-treat neurological disabilities, as well as increased mortality rates. Thus, identification of patients at high risk of RS is crucial. The PLANS model provides a structured framework for guiding secondary prevention interventions by stratifying patients according to their risk of recurrent strokes. High-risk patients identified by the model could benefit from intensified guideline-based interventions, including strict blood pressure management, smoking cessation programs, and tailored antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapies, as recommended by the AHA/ASA guidelines. Conversely, for low-risk patients, the model supports de-escalation of interventions, reducing unnecessary treatments and minimizing potential side effects. Future research should evaluate the effectiveness of PLANS-guided interventions in improving RS prevention and clinical outcomes, thereby validating its practical utility in routine clinical settings. Therefore, the establishment of our new PLANS model is of potential high clinical significance in predicting the outcome of patients with MIS and guiding optimal clinical management to prevent RS.

Comparison with traditional predictors of long-term outcomes

The Essen model is currently a widely used scoring system for evaluation of ischemic stroke and prediction for the occurrence of RS. This traditional noninvasive model that is based on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risk factors (age, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, prior myocardial infarction, peripheral artery diseases, other cardiovascular diseases, and prior ischemic stroke/transient ischemic attack). The predictive value of the Essen model for RS is relatively poor,25 and is not designed for the patients with MIS. The ESRS is widely used for evaluating the risk of recurrent strokes; however, it has notable limitations when applied to patients with MIS. The ESRS predominantly focuses on traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as age, hypertension26, diabetes, and smoking, without considering the unique characteristics of MIS or stroke subtype. Furthermore, the ESRS lacks measures of initial stroke severity, such as the NIHSS score, which has been demonstrated to significantly influence recurrence risk. The PLANS model addresses these shortcomings by integrating stroke-specific variables, including physical activity, large artery atherosclerosis subtype, and NIHSS score at admission. These additions enhance the model’s predictive accuracy and clinical utility, making it more applicable for individualized risk stratification and secondary prevention in patients with MIS. Our new PLANS model uses 4 specific variables (PA, stroke type, neurologic deficits at admission, and smoking) is specific for patients with MIS, simple and easy to use with a favorable predictive value for RS.

Roles of the PLANS components in RS

Using machine learning algorithms, we developed a new PLANS model based on 23 clinical variables to predict the risk of RS for patients with MIS. Internal validation indicated that PA, stroke type, neurologic deficits at admission, and smoking are the four most important contributors to the model. A high admission NIHSS score was identified as the most important risk factor for RS. The present study also showed that PA was strongly associated with a reduced risk for RS events in MIS patients. This is not surprising since PA could improve vascular endothelial function and reduce the risk of ischemic stroke27. PA could also have beneficial effects on atherosclerosis28, hypertension26,29, insulin resistance30, and dyslipidemia31,32, thus, effectively decreasing the risk of ischemic stroke. Smoking is known to promote thrombosis and reduce cerebral blood flow via arterial vasoconstriction33,34, and increase RS risk following stroke35,36. There is a dose-related relationship between smoking and stroke recurrence37. The present study showed that smoking was also an independent risk factor for 1-year RS in patients with MIS. Thus, smoking cessation should be an important part of management plan to prevent RS in MIS patients.

The present study demonstrated that the RS rate was significantly higher in patients with MIS caused by LAA stroke than those due to other subtypes of stroke. This finding was consistent with previous studies38. The increased risk for RS in MIS patients related to LAA could be due to the possibility that there may be an ongoing thrombo-embolic process in the evolving atherosclerotic plaques in carotid arteries. Thus, a distal embolization or hemodynamic compromise due to critically stenotic or occluded arteries may occur again, leading to RS. The present study also suggested that coexistence of LAA and smoking could significantly increase the risk of RS in MIS patients. The interaction between LAA and smoking to significantly increase the risk for RS could be a result from the effect of smoking on the progression of atherosclerotic lesions in carotid arteries and development of thrombo-embolism in atherosclerotic arteries39.

Limitation

The present study has several limitations that warrant addressing in future research. Firstly, the study was conducted at a single center with a relatively small sample size, which may limit the generalizability and external validity of the findings. Secondly, our research did not evaluate all stroke subtypes, hence the effectiveness of the PLANS model in other stroke subtypes remains unverified. Future iterations of the PLANS model will incorporate multicenter, multiethnic cohorts to enhance its predictive accuracy and improve its generalizability across diverse populations. Additionally, although our model demonstrated satisfactory predictive performance within the current sample, it requires external validation in independent, multicenter cohorts to confirm its robustness, reliability, and predictive accuracy. While our study focused on traditional stroke risk factors, future models should consider incorporating additional variables, such as medication adherence and socioeconomic factors, to further refine predictive accuracy and enhance the comprehensiveness of the model. Lastly, our study did not assess the impact of specific interventions based on the predictive results of the PLANS model on the prevention of stroke recurrence, which merits further investigation in subsequent studies.

Association of Plans models with clinical practice guidelines

The PLANS prediction model developed in this study could be placed in the context of recent clinical practice guidelines for secondary stroke prevention. For instance, the AHA/ASA guidelines for preventing recurrent stroke after TIA or minor stroke recommend aggressive risk factor management for patients at high risk. The AHA/ASA 2021 guidelines emphasize individualized secondary stroke prevention strategies, including the optimization of antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy, smoking cessation, physical activity promotion, and risk factor management such as controlling blood pressure and diabetes. The PLANS model aligns closely with these recommendations by integrating variables such as physical activity, stroke severity (NIHSS), and smoking status, providing a more comprehensive framework for risk stratification16. The PLANS model may aid in identifying the highest-risk patients who could potentially benefit most from the intensive interventions suggested in the guidelines. It could also help stratify lower-risk patients who may not need such aggressive treatments. Relating the PLANS model to guideline recommendations may assist readers in understanding its possible clinical utility and implications for practice. Further studies could also explore using the model to guide individualized secondary stroke prevention. In summary, explaining predictive models in the context of guidelines is very important for understanding their clinical meaningfulness.

Conclusion

Data from this study showed that LAA stroke, admission NIHSS score, smoking, and PA were independently associated with the risk of RS in patients with MIS. The new PLANS model could be used to predict the risk of RS for MIS patients to optimize the secondary prevention strategies for the high-risk patients. However, a large multicenter prospective study is needed to validate the new model on predicting the risk of RS in MIS patients.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Wang, Y. L. et al. Burden of stroke in China. Int. J. Stroke 2(3), 211–213 (2007).

Sartor-Pfeiffer, J. et al. Computed tomography perfusion imaging-guided intravenous thrombolysis in acute minor ischemic stroke. Front Neurol. 14, 1284058 (2023).

Rostanski, S. K. et al. Infarct on Brain Imaging, Subsequent Ischemic Stroke, and Clopidogrel-Aspirin Efficacy: A Post Hoc Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 79(3), 244–250 (2022).

Kleindorfer, D. O. et al. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 52(7), e364–e467 (2021).

Pan, Y. et al. LDL-C levels, lipid-lowering treatment and recurrent stroke in minor ischaemic stroke or TIA. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 7(4), 276–284 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Factors affecting the outcomes of tirofiban after endovascular treatment in acute ischemic stroke: Experience from a single center. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 29(3), 957–967 (2023).

Johnston, S. C. et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 369(9558), 283–292 (2007).

Merwick, A. et al. Addition of brain and carotid imaging to the ABCD(2) score to identify patients at early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Neurol. 9(11), 1060–1069 (2010).

Kernan, W. N. et al. The stroke prognosis instrument II (SPI-II): A clinical prediction instrument for patients with transient ischemia and nondisabling ischemic stroke. Stroke 31(2), 456–462 (2000).

Diener, H. C., Ringleb, P. A. & Savi, P. Clopidogrel for the secondary prevention of stroke. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 6(5), 755–764 (2005).

Chandratheva, A., Geraghty, O. C. & Rothwell, P. M. Poor performance of current prognostic scores for early risk of recurrence after minor stroke. Stroke 42(3), 632–637 (2011).

Foschi, M. et al. Real-world comparison of dual versus single antiplatelet treatment in patients with non-cardioembolic mild-to-moderate ischemic stroke: A propensity matched analysis. Int. J. Stroke https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.041660 (2024).

De Matteis, E. et al. Divergence Between Clinical Trial Evidence and Actual Practice in Use of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Transient Ischemic Attack and Minor Stroke. Stroke 54(5), 1172–1181 (2023).

Fischer, U. et al. What is a minor stroke?. Stroke 41(4), 661–666 (2010).

Adams HP, Jr., Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke, 35–41. (1993).

Huang, Z. X. et al. Lifestyles correlate with stroke recurrence in Chinese inpatients with first-ever acute ischemic stroke. J. Neurol. 266(5), 1194–1202 (2019).

Pencina, M. J., D’Agostino, R. B. & Vasan, R. S. Statistical methods for assessment of added usefulness of new biomarkers. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 48(12), 1703–1711 (2010).

Collins, G. S., Reitsma, J. B., Altman, D. G. & Moons, K. G. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ 350, g7594 (2015).

Latouche, A., Porcher, R. & Chevret, S. Sample size formula for proportional hazards modelling of competing risks. Stat Med. 23(21), 3263–3274 (2004).

Collaborators, G. B. D. S. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 20(10), 795–820 (2021).

Ding, Q. et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Ischemic Stroke, 1990–2019. Neurology 98(3), e279–e290 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Chinese Stroke Center Alliance: a national effort to improve healthcare quality for acute stroke and transient ischaemic attack: rationale, design and preliminary findings. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 3(4), 256–262 (2018).

Tomari, S. et al. One-Year Risk of Stroke After Transient Ischemic Attack or Minor Stroke in Hunter New England, Australia (INSIST Study). Front. Neurol. 12, 791193 (2021).

Wussler D, du Fay de Lavallaz J, Mueller C. Five-Year Risk of Stroke after TIA or Minor Ischemic Stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 379(16): 1580. (2018).

Thompson, D. D., Murray, G. D., Dennis, M., Sudlow, C. L. & Whiteley, W. N. Formal and informal prediction of recurrent stroke and myocardial infarction after stroke: a systematic review and evaluation of clinical prediction models in a new cohort. BMC Med. 12, 58 (2014).

Panchawagh, S., Karandikar, Y. & Pujari, S. Antihypertensive therapy is associated with improved visuospatial, executive, attention, abstraction, memory, and recall scores on the montreal cognitive assessment in geriatric hypertensive patients. Cereb. Circ. Cogn. Behav. 4, 100165 (2023).

Schmidt, W., Endres, M., Dimeo, F. & Jungehulsing, G. J. Train the vessel, gain the brain: physical activity and vessel function and the impact on stroke prevention and outcome in cerebrovascular disease. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 35(4), 303–312 (2013).

Yang, D. et al. Physical Activity Is Inversely Associated With Severe Intracranial Stenosis in Stroke-Free Participants of NOMAS. Stroke 54(1), 159–166 (2023).

da Silva, G. C. R. et al. Association of Early Sports Practice with Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Community-Dwelling Adults: A Retrospective Epidemiological Study. Sports Med. Open 9(1), 15 (2023).

Wanders, L. et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior show distinct associations with tissue-specific insulin sensitivity in adults with overweight. Acta Physiol. (Oxf) 237(4), e13945 (2023).

Kim, J. H. et al. Development of a Digital Healthcare Management System for Lower-Extremity Amputees: A Pilot Study. Healthcare (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010106 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Trajectories of 24-Hour Physical Activity Distribution and Relationship with Dyslipidemia. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15020328 (2023).

Rogers, R. L., Meyer, J. S., Judd, B. W. & Mortel, K. F. Abstention from cigarette smoking improves cerebral perfusion among elderly chronic smokers. JAMA 253(20), 2970–2974 (1985).

Ambrose, J. A. & Barua, R. S. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 43(10), 1731–1737 (2004).

Chen, J. et al. Impact of Smoking Status on Stroke Recurrence. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 8(8), e011696 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Risk factors affecting the 1-year outcomes of minor ischemic stroke: results from Xi’an stroke registry study of China. BMC Neurol. 20(1), 379 (2020).

Luo, J. et al. Cigarette Smoking and Risk of Different Pathologic Types of Stroke: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Front Neurol. 12, 772373 (2021).

Hou, X. & Chen, H. Proposed antithrombotic strategy for acute ischemic stroke with large-artery atherosclerosis: focus on patients with high-risk transient ischemic attack and mild-to-moderate stroke. Ann. Transl. Med. 8(1), 16 (2020).

Ji, R. et al. Current smoking is associated with extracranial carotid atherosclerotic stenosis but not with intracranial large artery disease. BMC Neurol. 17(1), 120 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere gratitude to the patients and their families for their invaluable assistance and active participation, which were instrumental in bringing this research to fruition. Their contributions have not only enriched our study but also underscored the importance of collaborative efforts in advancing medical understanding and care.

Funding

ZXH was supported by the Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau Key Research and Development Program (2024B03J0436). The funding source had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The data in the study were fully accessible to Z.X. H who was responsible for the integrity and accuracy of the data analysis; Design and concept: Z.X. H, Z.G. L; Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Z.X. H, H.K. L, Y. L, Y.Y. D, J.G. L, Z.G. L; Drafting of the manuscript: Z.X. H, Y. L; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors; Statistical analysis: Z.X. H, J.G. L, Z.G. L; Administrative, technical, or material support: H.K. L, Y.Y. D, Y. L; Supervision: Z.X. H, Z.G. L; All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study involves a retrospective analysis conducted at a single center, and its foundation is grounded in prospective research. It received approval from the Ethical Committee of Guangdong Second Provincial General Hospital (ethics code: 20120812-GD2H).

Consent for publication

Throughout the study, we rigorously adhered to the pertinent requirements and ethical standards outlined in the Helsinki Declaration. Additionally, all patients participating in the study provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, ZX., Lu, H., Lu, Y. et al. The PLANS model predicts recurrent strokes in patients with minor ischemic strokes. Sci Rep 15, 9187 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93741-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93741-8