Abstract

In this article, we introduce an innovative methodology for image segmentation utilizing neutrosophic sets. Neutrosophic set components exhibit superior reliability in image processing due to their adeptness at managing uncertainty. The swift proliferation of neutrosophic sets research is attributed to its efficacy in addressing uncertainties in practical scenarios. Effective segmentation requires the resolution of uncertainties. This article’s principal aim is to achieve multi-class segmentation through uncertainty analysis. The \(\mathscr {T}_{1k}\) segmentation method pertains to type 1, encompassing truth and falsity membership functions. In this method, multiclass segmentation is possible based on the image intensity values of the neutrosophic membership functions. As a result of this research, the article proposes the finding of image segmentation through the neutrosophic set. An experimental set of biometric iris data will be the main focus of the experiment. The analysis employs real-time iris image data. The image data were sourced from the CASIA V1 iris image database. Noise was introduced into the images for analytical purposes, specifically Gaussian and Poisson noise. The evaluation metrics include the Jaccard, MIOU, precision, recall, F1 score, and accuracy. As a result of the application of this methodology, an impressive segmentation score of 85% was obtained.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The method of segmentation in image processing is utilized to reveal various characteristics of the image, such as color, texture, contrast, shape, and regions. By employing segmentation, we can perform image classification and object detection tasks. Segmentation plays a vital role in real-world applications, including biometric image segmentation, satellite image segmentation, infrared image segmentation, and medical image segmentation. The superpixel-based method is employed to segment the image, utilizing various techniques. However, employing this approach to segment and identify objects in complex images poses a significant challenge. The neural network model is considered a more advanced and effective technique for segmentation. Nonetheless, this model requires abundant supervised data and substantial hardware and software support, demanding high-quality training data and labels. Researchers are focusing on unsupervised segmentation models like K-means clustering1, to address this particular issue. According to Yu2, segmentation involves tackling various difficult tasks, including feature representation, model design, and optimization. Issues such as sparse annotations, class imbalance, overfitting, long training times, and gradient vanishing, especially in semantic segmentation, needs special attention and efforts to resolve them. Several traditional segmentation techniques used in semantic segmentation comprise edge detection region division, clustering method, random walks, co-segmentation, and clustering-based co-segmentation. In semantic segmentation, neural network models like encoder-decoder architecture, skip connections, and attention mechanisms are commonly employed. A range of architectures, including VGG, Inception, ResNet, DenseNet, and U-Net, can be used to construct neural network models for segmentation.

Chen et al.13 introduced the multiple-kernel fuzzy c-means algorithm, which relies on a combination of kernels. To enhance segmentation, this approach updates the linear coefficients of the composite kernels through derivation rules. For robust clustering, it can accommodate heterogeneous data, such as remote sensing images14. Addressing noise is a primary strength of the fuzzy c-means (FCM) algorithm, as it leverages membership functions. When dealing with uncertainty noise, the most recommended algorithm is the intuitionistic fuzzy c-means (IFCM) algorithm15. One drawback of this method is its failure to utilize any local spatial data from noise images. To tackle this limitation, the improved intuitionistic fuzzy c-means (IIFCM)3 technique can resolve the local spatial information of the noise image.

Compared to the IFCM, the IIFCM grants access to more information. These methodologies strongly advocate for the integration of fuzzy sets, offering one of the potential theories for computer vision segmentation.

Fuzzy set theory, previously covered, is a top-notch method for segmenting images based on membership functions and uncertainty functions. The concept of an extended fuzzy set, commonly known as the neutrosophic set (NS), becomes relevant for image segmentation when its applicability is justified. The only uncertainty and membership functions addressed by the fuzzy set are the membership, non-membership, and indeterminacy functions. Originally developed by Smarandache16, the neutrosophic set utilizes membership functions to determine the crisp set. By incorporating both non-membership and indeterminacy functions, the neutrosophic set allows for a more comprehensive representation of uncertainty in image segmentation, potentially leading to improved segmentation outcomes. Furthermore, the usage of membership functions captures inherent uncertainty present in real-world scenarios and aids in the decision-making process. The medical image segmentation field shows considerable interest in neutrosophic-based image segmentation, as conventional techniques often struggle with complex and ambiguous structures in medical images. Leveraging the neutrosophic set theory has the potential to enhance the accuracy and reliability of medical image segmentation algorithms, primarily due to its ability to manage uncertainty and ambiguity. Additionally, the integration of membership functions allows for subjectivity and expert knowledge, resulting in higher-quality segmentation outcomes for medical applications.

In 2009, Guo et al.5 implemented the NS in image processing, employing the entropy of the membership images as a metric to evaluate its performance, which outperformed traditional segmentation approaches in terms of accuracy. The NS approach also facilitated better customization and adaptation to various image data settings through the incorporation of expert information via membership functions. Faraji et al.6, in 2013, applied the NS theory to biometric images, focusing on facial recognition as the primary objective. Utilizing NS membership functions in the preprocessing method helped eliminate noise and successfully retrieve facial characteristics using linear discriminant analysis on the NS-preprocessed face image. This approach demonstrated potential improvements in facial recognition accuracy, while the NS membership functions played a significant role in reducing the impact of noise on the retrieved facial characteristics, thereby enhancing recognition effectiveness.

In 2010, Zhang et al.4 utilized the NS idea in image segmentation to handle images with uniform backgrounds and objects that have blurry edges. This concept considers falsity memberships as the image’s background and truth memberships as its objects. To reduce noise in the uniform image, the S-function was applied to the truth membership functions, effectively enhancing the precision and clarity of objects with blurry edges. This method outperformed more established segmentation techniques, particularly when dealing with uniform backgrounds and objects with fuzzy borders. To determine the parameter values, the maximum entropy technique was employed due to its excellent ability to manage uncertainty and represent the fundamental distribution of the data. This optimization ensures that the segmentation process is well-tuned, leading to overall improved performance based on the chosen parameter values. The suggested water shade method was compared with the Sobel operator and the mean-shift approach. Various segmentation techniques, such as pixel-based, edge-based, and region-based approaches, were utilized. The pixel-based approach focuses on specific pixels and categorizes them into groups based on their intensity levels. In contrast, the edge-based approach distinguishes different regions based on the visible edges in the image. Lastly, the region-based technique groups pixels together based on their similarity in color, texture, or other properties. Through the comparison of different approaches, it was found that the NS-based water segmentation approach performed better on noisy and non-uniform images due to its ability to handle indeterminacy effectively.

Sengur et al.17 proposed an automated thresholding system that concentrates on NS-domain region and boundary-based image segmentation. Key elements, such as color and texture, play a significant role in aiding the algorithm in segmenting the images. By employing the wavelet transform and the NS domain, the suggested image segmentation technique successfully extracted color and texture information, leading to high accuracy in picture segmentation. The unsupervised k-means clustering technique was used to evaluate the proposal with real-world images, and the performance score varied based on the block size, highlighting the importance of choosing the appropriate block size for optimal results. In recent research, Vinoth and Devarasan7 employed innovative overset and underset methods to threshold biometric images like fingerprints and facial images. The article explores the concepts of global and adaptive thresholding. The novel threshold approach is based on the membership function of the NS components. In the global thresholding process, if the membership components meet the overset requirements for an intensity value, the binary image is segmented according to the membership intensity values. The threshold value is treated as a dependent variable, similar to the underset method. However, for adaptive thresholding, where local block adaptive methods are used to determine threshold values, this variable is unnecessary. Individual face and image data sources were analyzed for each thresholding technique. The global thresholded image was evaluated using various methods, including normalization, min-max normalization, and a combination of Otsu and binary threshold methods. The adaptive thresholding methods, particularly Gaussian and c-means, demonstrated superior performance in accurately segmenting face and image data compared to the global thresholding methods. This indicates that modifying threshold values based on the local characteristics of images can improve segmentation accuracy. To validate the concept, fingerprint data analysis was conducted using datasets like SD302a, SD302d, Soco, FVC2000, FVC2002, and FVC2004, which are commonly used in fingerprint analysis and offer diverse fingerprint images. For face image data, databases such as CWF, CBCL, RF, MEDS-I, and MEDS-II were considered, chosen for their size and wide variety of facial expressions, lighting conditions, and poses. Testing adaptive thresholding techniques on multiple databases enhanced the robustness and generalizability of the results. The global thresholding method achieved an impressive \(94\%\) accuracy, demonstrating the effectiveness of adaptive thresholding techniques in accurately identifying and segmenting faces in various image databases. These findings indicate that adaptive thresholding methods have practical applications in facial recognition systems and computer vision algorithms for real-world scenarios. The expected performance score for the NS-based thresholding segmentation with the adaptive approach is \(96\%\), showcasing even better accuracy potential.

Gender detection is a part of biometric recognition, involving the categorization of gender using 3-D models of people’s faces as demonstrated in the article8. The cutting-edge face-recognition algorithm selected for this task excels at identifying the gender of an image. The analysis utilized the supervised Face Recognition Grand Challenge v2 dataset and employed techniques like Face-Similarity, Kernelized k-Nearest-Neighbors, and k-Nearest-Neighbors. The gender detection model under consideration relies on spatial features. Back in 2007, the method was implemented, and thorough observations were made during its evaluation. Remarkably, the proposed model achieved a mean MDS accuracy exceeding \(99\%\) and displayed a gender classification accuracy of approximately \(94\%\). Such high accuracy reflects the model’s ability to precisely identify the gender of images. The study’s findings strongly indicate that this model can serve as a valuable resource in various applications where gender identification holds significance, such as demographic analysis or targeted advertising.

Nishino et al.18 conducted an analysis to extract visual data from a single eye image. They utilized geometric-based anatomical studies to estimate the 3D location and orientation, which greatly aids in visually identifying human eyes. The mentioned studies inspire us to engage in projects related to iris recognition systems. We chose to implement an NS-based domain because fuzzy and NS have become more prominent in segmentations and have made significant contributions over the last few decades. When approaching via the NS domain, the images are analyzed with three components, leading to more reliable results using this method. Due to the delicate nature of biometrics and the need to handle ambiguous situations, we must consider and address such cases. The NS is capable of effectively managing uncertainties, as evident from its association with the indeterminacy function. Consequently, our objective is to develop a novel approach for image segmentation by leveraging the NS domain process. Table 1 presents the achievement proposal for NS and iris image segmentation to date. The field of medicine has witnessed a rapid expansion of neutrosophic segmentation in recent times. El-Shahat19 made strides in enhancing the optimization of neutrosophic image segmentation. The progress in neutrosophic segmentation methods shows promise for revolutionizing medical imaging, potentially leading to better diagnostic precision and patient care outcomes. By refining neutrosophic image segmentation optimization, medical professionals may be able to identify and examine minute abnormalities in medical images with greater accuracy. These innovations could pave the way for earlier disease identification and more personalized treatment approaches across various medical specialties. Abdulbaqi20 presents a comprehensive study on the application of neutrosophic logic in medical image processing and analysis. Neutrosophic logic, an extension of fuzzy logic, introduces degrees of truth, indeterminacy, and falsity to handle uncertainty and inconsistency in data. The paper explores how this approach can enhance various aspects of medical imaging, including noise reduction, image enhancement, segmentation, feature extraction, and classification. Ghanbari21 proposes a new method for the completion of images and videos based on neutrosophic theory, which deals with uncertainty both in the spatial and intensity domains. Neutrosophic is used to interpret the indeterminacy of the images, allowing more accurate segmentation and better handling of incomplete data. The proposed method first segments the image using a neutrosophic-based segmentation and then uses the segmented information to guide the completion of missing regions. For video completion, two steps of the method are introduced, separating static backgrounds from moving objects. The background is reconstructed using image completion based on neutrosophic segmentation, and the foreground is completed by identifying appropriate data that best match the missing parts; these data are chosen using a contour-based method, which applies this method to neutrosophic sets to reach the most suitable data.

The above works of literature make the best eye-openers in the field of image segmentation. Despite the impressive segmentation score achieved, several challenges were encountered during the experiment. One major difficulty was managing the noise levels introduced into the images, which occasionally led to reduced accuracy in certain cases. Additionally, fine-tuning the membership functions to optimize performance across all metrics required significant computational effort and expertise. With that motivation, segmentation we introduced the concept of image segmentation with the help of a neutrosophic set. Neutrosophic sets enhance segmentation by effectively handling the inherent uncertainty present in image data, allowing for more accurate differentiation between classes. They enable the integration of truth, indeterminacy, and falsity values, which provides a robust framework for capturing complex image features. This capability results in improved segmentation performance, particularly in challenging scenarios where traditional methods may struggle. Through this, we are trying to achieve our objective which is image segmentation via neutrosophic sets.

This article introduces a model technique for image segmentation that relies on intensity intervals. The introductory terminology used in the article is presented in the rest of Section "Preliminaries". In Section "Proposed methodology", we provide explanations of the functions, definitions, and theorems of the proposed methods. The experimental findings are discussed in Section "Experimental results", which includes the validation of the Gaussian and Poisson noise analyses. Section "Conclusion" contains the conclusion of our work and an outlook on the potential future features.

Preliminaries

Definition 1

Let X be an universe of discourse, with a generic element in X denoted by x, then a neutrosophic set (NS) , A is an object having the form16

where the functions \(T, I,F:X \rightarrow ]^{-}0,1^{+}[\) define respectively the degree of truth, the degree of indeterminacy and the degree of falsity of the element \(x\in X\) to the set condition.

Definition 2

A neutrosophic image \(\varGamma (i,j)\) is characterized with neutrosophic components which are T, I, F where \(\varGamma (i,j)\) are the pixel values of the image. Universally for neutrosophic image is approach with gray level images. Therefore the image neutrosophic set is defined as5

In general mean values and standard deviation of the image are taken as truth and indeterminacy memberships. The image transformation pixels of the image is made by the following formulae

where \(\bar{p}(i,j)\) is the pixel mean in the region \(w*w\) and w is generally \(w = 2n+1, \ \ (n\ge 1) .\)

Definition 3

(Gaussian noise) The technique of Gaussian noise involves employing the probability density function of the distribution to model statistical noise. In image analysis, the standard deviation is utilized as a parameter because the Gaussian mean is assumed to be zero. This is given as

where x represents the intensity, \(\bar{x}\) is the mean value of x, and \(\sigma\) is its standard deviation. The standard deviation squared is called the variance.

Definition 4

(Poisson noise) Photon noise is synonymous with Poisson noise. The Poisson noise method was employed for cases where the intensity occurrences were low. The Poisson distribution utilizes a constant mean rate in its discrete probability distribution.Photon noise is synonymous with Poisson noise.

the discrete outcome is the number of times an event occurs, represented by k.

Definition 5

Let \(f(x, y) = \mathscr {I}(i, j)_{m\times n} \in \mathbb {R}^{2}\) be an image then the zero padding for neutrosophic image \(P_{k_{0}}\) is defined with respect to h as7

where \(k = 2\mathbb {N}+1\), \(3\le k \le \min ( m ,n)\) and \(h = k\mod (2)\).

Definition 6

Let \(f(x, y) = \mathscr {I}(i, j)_{m\times n} \in \mathbb {R}^{2}\) be an image then the one padding for neutrosophic image \(P_{k_{1}}\) is defined with respect to h as7

where \(k = 2\mathbb {N}+1\), \(3\le k \le \min ( m ,n)\) and \(h = k\mod (2)\).

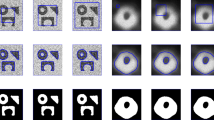

Figure 1 displays a visualization of the Iris image by membership.

Proposed methodology

Let \(\mathscr {I}: \omega \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) an image the intensity defined over \(\omega \subseteq \mathbb {R}^{2}\). The intensity neutrosophic components are \(T_{\omega } , I_{\omega }, F_{\omega }\) such that \(\exists x (t_{x}, i_{x}, f_{x}) \subseteq ^{-}]0, 1[^{+}\) where \(x\in \omega\) then

-

\((T_{x},I_{x}, F_{x}) \subseteq P_{NR} (\mathscr {I})\)

-

\(T_{x_{i}}\bigcap T_{x_{j}} = \phi\), \(I_{x_{i}}\bigcap I_{x_{j}} = \phi\) and \(F_{x_{i}}\bigcap F_{x_{j}} = \phi\), \(\forall i \ne j\)

-

\(\bigcup _{i = 1}^{N} T_{\omega _{i} }\subseteq T_{\omega }\), \(\bigcup _{i = 1}^{N} I_{\omega _{i} }\subseteq I_{\omega }\), \(\bigcup _{i = 1}^{N} F_{\omega _{i} }\subseteq F_{\omega }\)

Neutrosophic semantic segmentation

Definition 7

(T range function) Let \(\mathscr {I}: \omega \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) be an image with \(\mathscr {I}_{x} \in \omega\) intensities in \(\mathbb {R}^{2}\). The neutrosophic components of the image \(T_{\omega }\) derived from the above equations. Then the T ranges for the k segmentation is derived as following function

Definition 8

(\(T_{k}\) segmentation labeling) Let \(T_{\omega }\) is the neutrosophic truth membership of the neutrosophic component and \(g(T_{k})\) be the range function of the image \(\mathscr {I}\) then the \(T_{k}\) segmentation labeling is defined as follow

Definition 9

(F range function) Let \(\mathscr {I}: \omega \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) be an image with \(\mathscr {I}_{x} \in \omega\) intensities in \(\mathbb {R}^{2}\). The neutrosophic components of the image \(F_{\omega }\) derived from the above equations. Then the F ranges for the k segmentation is derived as following function

Definition 10

(\(F_{k}\) segmentation labeling) Let \(F_{\omega }\) is the neutrosophic false membership of the neutrosophic component and \(g(F_{k})\) be the range segmentation function of the image \(\mathscr {I}\) then the \(F_{k}\) segmentation labeling is defined as follow

Definition 11

(\(\mathscr {T}_{1k}\) semantic segmentation function) Let T, I, F be the neutrosophic components of the image \(\mathscr {I}\) then the neutrosophic based type 1 semantic segmentation function is defined as

Definition 12

Let \(\mathscr {I}: \omega \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^{2}\) be an image then the element is neutrosophic independent if

The image is called as neutrosophic independent image if \(\bigcup _{i=1}^{N}T_{\omega _{i}} \vee \bigcup _{i=1}^{N}I_{\omega _{i}} \vee \bigcup _{i=1}^{N}F_{\omega _{i}}\) neutrosophic independent then

.

Definition 13

Let \(\mathscr {I}: \omega \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^{2}\) be an image then the element is neutrosophic dependent if

The image is called as neutrosophic independent image if \(\bigcup _{i=1}^{N}T_{\omega _{i}} \wedge \bigcup _{i=1}^{N}I_{\omega _{i}} \wedge \bigcup _{i=1}^{N}F_{\omega _{i}}\) neutrosophic dependent then

Theorem 1

Let \(\mathscr {I}: \omega \rightarrow 1\) for \(\varGamma (P_{k_{1}})\) then \(\ \exists \ I_{\omega }, F_{\omega }\) are neutrosophic independent image.

Proof

Consider the image \(\mathscr {I} : \omega \rightarrow 1\) then \(\mathscr {I} = (x_{11} ,x_{12}, ....x_{mn}) \in (1, 1, ...1)\).

Therefore \(\mathscr {I}(T_{\omega }) = (x_{11} ,x_{12}, ....x_{mn})\) .

Then \(\mathscr {I}(\delta _{\omega } ) \rightarrow 0\) such that \(\mathscr {I}(I_{\omega }) = (z_{11} ,z_{12}, ....z_{mn}) \Rightarrow \frac{(x_{11}, x_{12,}, ... x_{mn} )- \min (\delta _{\omega } )}{\min (\delta _{\omega }) -\max (\delta _{\omega } )} \rightarrow 0.\)

Since \(F_{\omega } = (T_{\omega })^{c} \Rightarrow (y_{11} ,y_{12}, ....y_{mn}) \in (0, 0, ...0)\) .

\(\square\)

Theorem 2

Let \(\mathscr {I}: \omega \rightarrow 0\) for \(\varGamma (P_{k_{0}})\) then \(\ \exists \ T_{\omega }, I_{\omega }\) are neutrosophic independent image.

Proof

Consider the image \(\mathscr {I} : \omega \rightarrow 1\) then \(\mathscr {I} = (x_{11} ,x_{12}, ....x_{mn}) \in (0, 0, \dots 0)\).

Therefore \(\mathscr {I}(T_{\omega }) = (x_{11} ,x_{12}, ....x_{mn})\) .

Then \(\mathscr {I}(\delta _{\omega } ) \rightarrow 0\) such that \(\mathscr {I}(I_{\omega }) = (z_{11} ,z_{12}, ....z_{mn}) \Rightarrow \frac{(x_{11}, x_{12,}, ... x_{mn} )- \min (\delta _{\omega } )}{\min (\delta _{\omega }) -\max (\delta _{\omega } )} \rightarrow 0.\)

Since \(F_{\omega } = (T_{\omega })^{c} \Rightarrow (y_{11} ,y_{12}, ....y_{mn}) \in (1, 1, \dots 1)\) .

\(\square\)

Theorem 3

Let an image \(\mathscr {I}\in \mathbb {R}^{2}\) with neutrosophic components T, I, F for the neutrosophic block h. If \(I_{\omega }\) is neutrosophic independent then the \(\mathscr {T}_{1k}\) semantic segmentation \(g(T_{k_{l}})_{l = 1}^{n} = g(F_{k_{l}})_{l = n}^{1}\) where \(1 \le n \le k\).

Proof

Let \(\mathscr {I}\)’s truth, indeterminacy and falsity membership are T, I, F for the neutrosophic block h, and the segmentation size \(k = n\).

If \(T _{\omega }\) is the truth membership is \(\mathscr {I}\) then the membership intensity range function \(g(T_{k})\) is from the Equation 11\((t_{x_{1}} , t_{x_{2}},...t_{x_{n}})\). The segmentation label \(g(T_{k_{l}})\) is \((l_{1}, l_{2}, ...l_{n} )\). Similarly the falsity membership \(F\)'s membership intensity range function is \((f_{x_{1}} , f_{x_{2}},...f_{x_{n}})\) and \(g(F_{k_{l}})\) is \((l_{1}, l_{2}, ...l_{n} )\).

Since the indeterminacy \(I_{\omega }\) is neutrosophic independent of \(\mathscr {I}\) then \(\bigcup _{i=1}^{N}I_{\omega _{i}} \rightarrow 0\) the labels are

Since \(F_{\omega } = (T_{\omega })^{c}\) for neutrosophic independent \(I_{\omega }\) the labels are

Therefore the \(\mathscr {T}_{1k}\) semantic segmentation is \(g(T_{k_{l}})_{l = 1}^{n} = g(F_{k_{l}})_{l = n}^{1}\). \(\square\)

Theorem 4

Let an image \(\mathscr {I}:\rightarrow \omega\) with neutrosophic components T, I, F for the neutrosophic block h. If \(I_{\omega }\) is neutrosophic dependent then \(g(T_{k_{l}}) \ne g(F_{k_{l}})\).

Proof

Let consider the neutrosophic components T, I, F of the image \(\mathscr {I}\) as follows \(T = (t_{1}, t_{2} ,...t_{n}),\) \(I= (i_{1}, i_{2}, ...i_{n})\) and \(F= (f_{1}, f_{2}, ... f_{n}).\)

Since \(\mathscr {I}_{\omega }\) is dependent let \(g(T_{k_{l}})\) is \((l_{1}, l_{2}, ...l_{n}: \in (t_{x_{k_{n-1}}} ,t_{x_{k_{n}}}])\) and \(g(F_{k_{l}})\) is \((l_{1}, l_{2}, ...l_{n}: \in (f_{x_{k_{n-1}}} ,f_{x_{k_{n}}}])\).

If \(k_{n}\in l_{n}\) then \(g(f_{k}) = k_{n-\Delta n}\text { where } 1\le \Delta n \le k \in \mathbb {N}\).

\(\therefore g(T_{k_{l}}) \ne g(F_{k_{l}})\). \(\square\)

Theorem 5

Let \(\mathscr {I}:\rightarrow \omega\) be an image with neutrosophic components \(T_{\omega }, I_{\omega }, F_{\omega }\) if \(I_{\omega } \ \& \ F_{\omega }\) are neutrosophic independent then \(\exists \ \varGamma _{\omega \oplus } \subseteq T_{\omega }\).

Proof

Let \(I_{\omega }, F_{\omega }\) are neutrosophic independent \(I_{\omega } \rightarrow 0, F_{\omega } \rightarrow 0.\)

Since \(F_{\omega } = (T_{\omega })^{c}\) then \(T_{\omega } \rightarrow 1 .\)

From the Theorem 1 also for \(\varGamma (P_{k_{0}})\) then \(\varGamma _{\omega \oplus } \rightarrow 1.\)

Therefore \(\varGamma _{\omega \oplus } \subseteq T_{\omega } .\) \(\square\)

Theorem 6

Let \(\mathscr {I}:\rightarrow \omega\) be an image with neutrosophic components \(T_{\omega }, I_{\omega }, F_{\omega }\) if \(I_{\omega } \ \& \ T_{\omega }\) are neutrosophic independent then \(\exists \ \varGamma _{\omega \oplus } \subseteq F_{\omega }\).

Proof

Let \(I_{\omega }, T_{\omega }\) are neutrosophic independent \(I_{\omega } \rightarrow 0, T_{\omega } \rightarrow 0.\)

Since \(F_{\omega } = (T_{\omega })^{c}\) then \(F_{\omega } \rightarrow 1 .\)

From the Theorem 2 also for \(\varGamma (P_{k_{1}})\) then \(\varGamma _{\omega \oplus } \rightarrow 1.\)

Therefore \(\varGamma _{\omega \oplus } \subseteq F_{\omega } .\) \(\square\)

In conventional methodologies, multi class segmentation was executed utilizing the pixel values intrinsic to the image, in conjunction with a variety of machine learning algorithms or image processing techniques. Alternatively, the technique proposed in this manuscript enhances multi class segmentation through a decision-making paradigm established on piece wise functions tied to the membership functions of neutrosophic sets. For the \(\mathscr {T}_{1k}\) segmentation methodology, it is imperative to compute the values corresponding to truth and falsity ranges. Subsequently, based on the computed values of class segmentation, the segmentation labeling values are derived following the established definitions of segmentation labeling. Ultimately, the allocation of segmentation labels will be executed in alignment with the \(\mathscr {T}_{1k}\) formulation methodology.

Algorithm 1 meticulously delineates the comprehensive procedural framework of the \(\mathscr {T}_{1k}\) segmentation methodology, elucidating each critical step involved in its implementation. In this framework, the intensity values of the image are rigorously employed as the prominent features that aid in defining the image under consideration. Depending on the specific requirements dictated by the application at hand, it becomes imperative to establish and fix the dimensions of the image blocks that will be utilized during the segmentation process. Subsequently, the values of the segmentation classes will be determined and fixed by the principles governing multi class segmentation methodologies. The evaluation of the neutrosophic membership function values is executed through the application of the NS-feature extraction technique, which is pivotal for the subsequent analysis. Upon the determination of these membership values, the algorithm will be systematically developed to ascertain both the image range function and the corresponding segmentation labeling, utilizing the equations that span from 11 to 14 Furthermore, the equation labeled 15 is employed within Algorithm 1 to facilitate the identification and execution of multi class segmentation, thereby enhancing the overall efficacy of the segmentation process.

Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of the proposed methodology concerning existing scientific works. The table elucidates the insights derived from the proposed methodologies. The previously established methods, including the Watershed algorithm, linear discriminant analysis, K-Nearest Neighbors, and Hough transform, have been employed for the multi class segmentation task; however, they have proven inadequate in segmenting the images based on membership functions. The analysis utilizing membership functions is anticipated to mitigate the bias associated with uncertainties. Fuzzy sets are proficient in addressing this predicament. Nevertheless, fuzzy sets predominantly concentrate on membership functions exclusively. To enhance the conceptual framework, the intuitionistic fuzzy set is posited to effectively facilitate the analysis of both membership and non-membership functions. By scrutinizing membership, non-membership functions, and indeterminacy functions, can obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the image features. Our proposed methodology is designed to meet these requirements while simultaneously augmenting the efficacy of image segmentation. Although there exist overset and underset methodologies established in neutrosophic sets, such approaches are limited to binary classification scenarios, specifically thresholding problems. The proposed \(\mathscr {T}_{1k}\) method is capable of implementing multi class segmentation through the utilization of membership functions. A distinguishing feature of the proposed methodology is its incorporation of three membership functions for analysis, which facilitates piece wise calculations for image segmentation.

Experimental results

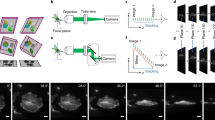

In this section, experiments are performed to evaluate the proposed technique. The details of the experimental data will be provided in the section that follows. The study’s experimental platform that supports the 11th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-1135G7 @ 2.40GHz 2.42 GHz with 16 GB of RAM capacity for the analysis. The Figure 2 shows the procedure of the proposed \(\mathscr {T}_{1k}\) segmentation method.

Analysis of sample images

The images of Cameraman, and Iris are used as instances in the analysis. The RGB view of the cameraman also includes the high and low intensity regions. We chose an iris image as an example since this study focused mostly on iris images. All of the sample images will be subjected to Gaussian and Poisson noise analysis. The neutrosophic kernel is fixed at \(h= 3\), the image size is set to \(\mathbb {R}^{2} =250\) for the initial analysis, and the variable system parameter k is considered when performing the analysis.

The Figure 3 shows that sample image’s output for various segmentation of \(k\)'s. The image’s \(\varGamma (l_{1})\) indicates the low brightness intensity label and \(\varGamma (l_{n})\) indicates the high brightness intensity label of the system. Depends on \(k\)'s value the segmentation region was covered from the intensity values. From the output of the visualization, the samples are proven that the system is neutrosophic dependent .

Figure 4 displays the sample image for segmentation with \(k = 5\). Each class of the \(k\)'s image patterns are demonstrated in the output. The patterns associated with the class label 1 are shown in the figure’s first column. Similar to the first column, the second, third, and so on show the respective patterns for classes 2, 3, and so on. The figure illustrates how few there are of the class 1 patterns at \(k = 5\) throughout all sample images. The class 2 patterns serve as thresholds for images that fall within the lower range of grayscale intensities. Lower gray indicates that it is in shades of gray but not complete darkness. Image class 2 accurately locates the retinal region for the iris. The patterns of the image’s central region and its surroundings are combined in this class. Additionally, it investigates some noise patterns across the entire retinal region of the image. Between the patterns of dark intensity and bright intensity are found classes 3 and 4. The image at the exact middle-intensity value is the class 3 threshold. In the task of retinal recognition, the test demonstrates that if we take the 5 classes of the iris image, then class 3 recognized the center region of the retina. For the iris image, this class identified the retina region more efficiently than the other classes. In the section after, more iris image evaluation is carried out. Class 4 seems into similar patterns to class 3, but when the image is black and white, this label recognizes the image’s edges. Therefore, it’s also possible that we might employ this suggestion to perform edge detection. However, the article’s primary focus is on the segmentation task. Class 5 obviously thresholds the image’s high range intensity patterns.

Evaluating the overall performance of the segmentation model, it is also important to analyze the class scores for each individual class. This allows us to identify any specific areas where the model may be struggling. The mean class accuracy provides an average measure of how well the model is performing for each class across all the sample images. Similarly, the pixel accuracy with and without background gives insights into the model’s ability to accurately classify pixels belonging to the target class. The percentage of correctly classified pixels in the predicted segmentation mask when compared to the truth intensity is recognized as pixel accuracy. According to the regions of the objects, this model predicts the object directly for k intensity values. The spatial overlap between the predicted and actual truth segmentation intensities is evaluated by IoU accuracy. This model provides the segmented boundary measurements as well as the segmented object shapes. The class scores for each class for the sample images can be obtained from Table 3. The table demonstrates each class score for all the images along with the mean class accuracy, pixel accuracy with and without background, and mIoU with and without background. The IoU is typically always less than pixel accuracy. Although the article assumed that it should concentrate on pixel accuracy because the analysis was based on intensity ranges, mIoU and Jaccard scores were considered evaluation metrics for the segmentation task in its entirety. The images were implemented with Gaussian noise and Poisson noise. Mean intersection over union, Jaccard similarity, precision, recall, F1-score, accuracy are consider for evaluation metrics.

Gaussian noise

It is important to consider the Iris image for both Gaussian and Poisson analyses. To achieve optimal performance in Gaussian analysis, parameters such as size, neutrosophic block h, standard deviation \(\sigma\), and k should be taken into account. The study examines three different sizes of \(\mathbb {R}^{2}\) are 32, 64, and 128. Neutrosophic kernel of sizes \(h=\) 3, 5, 7, and 9 are also analyzed. Similarly, segmentation analysis is carried out for \(k = 3, 4, 5, \text { and } 6\). When dealing with Gaussian noises, the standard deviation must be considered. Based on our observations, we have determined that the segmentation results can achieve maximum Jaccard values of \(85\%\) and a maximum mIOU of \(80\%\) with an accuracy rate of \(91\%\), as indicated by our analysis. These results were obtained using an image size of 64, which was consistent across all the aforementioned findings. Notably, when the image size is reduced to 32, the maximum scores for Jaccard and mIoU are both \(76\%\) and \(61\%\). These scores share a standard deviation of 5, indicating a relationship between them.

Moreover, for an image size of 32 and a high standard deviation, the highest Jaccard score is \(71\%\) for \(k = 3\), while the highest mIoU score is \(54\%\) for \(k = 4\). It is worth mentioning that the performance of six-class segmentation is generally poor, except when a low standard deviation is present. This suggests that the six-class segmentation method is not suitable for iris images. Intensity primarily manifests in the iris as lower gray and higher gray formations, making additional classes of segmentations relevant only when the image contains multiple object pixels. The findings indicate that six or more segmentations are not appropriate for segmenting iris images, and the article suggests that three or four-class segmentations are preferable.

The Gaussian standard deviation and the metric scores exhibit an inverse relationship. Figure 5, obtained through multiple iterations, validates this claim. The data indicated that performance should be higher for lower standard deviation values. Increasing the image size from 32 to 64 significantly improves the metric scores. The segmentation achieves a maximum mIoU and Jaccard score of \(81\%\) in this parameter model, with an accuracy rate of \(89\%\). The 64 image size consistently outperforms other sizes, regardless of the standard deviation values of the Gaussian noise. All metrics, including mIoU, Jaccard, precision, recall, F1, and accuracy, demonstrate better performance with this parameter model. The results suggest that an image size of 64 is suitable for iris image segmentation.

However, it is important to note that the 6-class segmentation model performs poorly for other image size parameters but performs well with a size of 64 when the standard deviation is low. Nevertheless, the 6-class segmentation is not the best option for segmenting iris images. Compared to sizes 32 and 64, size 128 performs slightly similar to 64. In most cases, a size of 128 outperforms a size of 32 for all parameters, including segmentation classes and standard deviations. Based on these findings, it is evident that a size of 64 is the most suitable parameter for segmenting iris images with a neutrosophic block size of \(h =3\).

Following the implementation of a neutrosophic block set to 5, the results obtained are as follows: When the block size is set to 32 and \(h = 5\), the accuracy and Jaccard score achieve \(86\%\) and \(78\%\), respectively. These scores represent the highest performance achieved by the system for the specified parameters. The maximum mIoU score of \(67\%\) is attained when \(k = 4\), and the \(\sigma\) is 10. Interestingly, this mIoU score contradicts the general expectation that it should always be lower than the Jaccard score. For the various k values, the performance score is shown in Figure 6. To improve the segmentation of iris images into four classes, both the h size and \(\sigma\) were increased. However, it is important to be cautious about potentially losing image information while reducing the working time of the system. A smaller neutrosophic block size of \(h = 3\) is preferred for in-depth analysis, but when time reduction is a priority, a larger block size is utilized. Comparing the four-class segmentation performance at an image size of 32 to other segmentation classes, it appears to be the most effective option for iris image segmentation. The same conclusion applies to an image size of 64, where the four-class segmentation still proves superior. The influence of standard deviation on the score has been discussed earlier, and it has been observed that even higher standard deviation values can produce satisfactory results. The performance of neutrosophic block \(h = 5\) with a size of 128 supports the initial findings. Thus, image size 64 with \(h = 5\) and segmentation size 128 are the preferred parameters.

For \(h = 7\), the best mIoU achieved in the four-class segmentation is \(76\%\), while the accuracy and Jaccard scores are \(83\%\) and \(72\%\), respectively. The optimal segmentation size for iris images is consistently found to be 64, as it performs similarly to the previously discussed outcomes with a size of 128. The use of a smaller system size leads to faster processing compared to 128. Thus, the 64-size parameter is the top choice for segmentation when focusing on efficiency and processing time. Similarly, when the \(\sigma\) is reduced, neutrosophic kernel \(h = 7\) also yields the highest probability score and provides better results when analyzing image intensities. The article strongly advocates, for semantic segmentation using the neutrosophic block approach, specifically for iris images. Neutrosophic block \(h= 9\) also performs well; however, due to the large size of the images, there is a risk of losing valuable image information during processing. Therefore, the block size of 9 is also considered a suitable but secondary option for segmentation.

Figure 8 emphasizes the performance scores of different parameters, including \(\mathbb {R}^{2}, k, \sigma , \text { and } h\). This is particularly relevant for the task of parameter decision-making. We can easily select the appropriate parameters by examining the visual representations. Consequently, we will adapt for these parameters to effectively segment vast amounts of data. Table 4 explores the performances of the \(\mathscr {T}_{1k}\) segmentation method for the sample images.

As a result, the segmentation underwent a thorough examination with Gaussian noise, encompassing several parameters. This examination enabled the determination of the most suitable neutrosophic membership elements for retinal recognition. The method presented here stands out as the top choice for retinal recognition through semantic segmentation, given its outstanding performance in the presence of such noise.

Analysis of Poisson noise

Poisson noise values represent discrete incidents occurring within a set interval, and these noises follow distributed pseudo-random sequences. The model used for acquiring photons on a photosite employs Poisson noise, resulting in limited variations in performance scores. The method’s benefit lies in nearly perfect normalization of all performance scores, eliminating confusion among researchers regarding proper performance. However, a drawback is that scores for each class-wise segmentation are quite comparable, potentially perplexing researchers in obtaining class-wise segmentation scores. Despite this, the fundamental notion of the mIoU score consistently being lower than others remains unaffected in this situation. Unlike Gaussian noise, where differences between other scores and mIoU score are significant, Poisson noise does not exhibit such discrepancies. For the parameter \(h = 3\), the minimum and maximum scores were \(85\%\) and \(99\%\), respectively. Remarkably, this method produced consistent results for all size parameters, encompassing 32, 64, and 128. The utilization of the best performance level attributes in this context has left us feeling puzzled. Furthermore, our examination encompassed k values of 3, 4, 5, and 6, and it was observed that the mIoU score decreases with increasing k, specifically for \(k = 5\). Notably, this approach’s advantage lies in the noise model, as it yields improved performance scores even for high k values. On the other hand, it appears that Gaussian noise was flawed in some way. Hence, the evaluation of both Gaussian and Poisson methods accounts for this unnoticed work within the proposal. The score analysis is viewed in Figure 7 for the various parameters. In that figure, it is evident that each neutrosophic block performs impressively.

As we discussed earlier, the Poisson noise model outperforms others in the low range of segmentation classes. Similar coverage for the \(\mathbb {R}^{2}\) attribute is observed across various parameters. The Poisson noise model consistently demonstrates exceptional performance and remains unaffected by changes in parameter values. In comparison, the Poisson model typically achieves superior performance, while the Gaussian noise model shows average performance when considering attributes. Obtaining the best scores for both the Poisson and Gaussian models would lead to a favorable segmentation. The class-level performance may differ depending on the distribution of noise in the model. To enhance our confidence, we simultaneously consider both noise models.

In Figure 9, the performance of the segmentation task is explored with a k value of 5 for the two noise models. Through visual representations, we can examine the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) region of each class. Figure 9a illustrates the ROC for the Gaussian noise model, while Figure 9b shows the ROC for the Poisson model. These visualizations help us grasp the performance characteristics of each noise model class. In the Poisson noise model, all classes exhibit comparable ROC regions. Although there are instances where this approach might be beneficial, it is not universally applicable. On the other hand, the Gaussian ROC region indicates that each class’s classification performance varies based on the parameters. When the parameters are set to high values, we may encounter lower-than-desired performance ratings.

CASIA-IrisV1 dataset

The CASIA Iris Image Database constitutes a prominent dataset within the domain of biometric recognition, with a particular emphasis on iris recognition systems. This database is developed and overseen by the Institute of Automation at the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CASIA). The principal aim of the CASIA Iris Image Database is to advance scholarly inquiry in the field of iris recognition and to assist in the formulation of algorithms pertinent to biometric identification or verification predicated on iris patterns. The fundamental aim of the CASIA Iris Image Database is to furnish a dependable and heterogeneous collection of iris images that facilitates the advancement and assessment of iris recognition systems. Such systems are employed in biometric authentication for security-related applications, encompassing access control, identity verification, and forensic examinations. Researchers may utilize this database to educate and evaluate algorithms concerning iris feature extraction, matching, classification and segmentation. The database functions as a normative benchmark for appraising the efficacy of various iris recognition algorithms. Researchers are afforded the opportunity to juxtapose their methodologies against established techniques in terms of accuracy, robustness, speed, and scalability. Due to the fact that the dataset comprises images from a large pool of subjects across a multitude of conditions (like fluctuating lighting, pupil expansion, and angles of imaging), it is ideally tailored for evaluating the versatility of iris recognition strategies.

The CASIA Iris Image Database ranks among the most frequently employed datasets within the iris recognition research community. By providing a publicly accessible and standardized repository of iris images, it guarantees that researchers are equipped with a common foundation for testing and validation purposes. This initiative fosters consistency in outcomes and cultivates a collaborative research atmosphere.

The CASIA Iris Image Database Version 1.0 (CASIA-IrisV1) consists of iris images captured using a custom iris camera designed in-house. To ensure uniform and adequate illumination of the iris, eight 850nm NIR illuminators are circularly arranged around the sensor. CASIA-IrisV1 contains a total of 756 iris images sourced from 108 eyes. For each eye, seven images are taken in two separate sessions using our proprietary CASIA close-up iris camera. The first session captures three samples, while the second session captures four samples. All images are saved in BMP format with a resolution of \(320 \times 280\). In CASIA-IrisV1, the pupil areas of all iris images have been automatically identified and replaced with a circular area of constant brightness. This alteration was implemented to conceal the specular reflections from the NIR illuminators, safeguarding our Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) related to the design of our iris camera, particularly the NIR illumination setup. It should be noted that this editing significantly simplifies iris boundary detection but has minimal to no impact on other aspects of an iris recognition system, such as feature extraction and classifier design.

The examination of sample images concerning the proposed segmentation technique reveals that parameters such as the neutrosophic block h, the number of segmentation classes, image dimensions, and noise values significantly influence the efficacy of the segmentation method. Given that the dimensions of the image can reconstruct the structural configurations of the objects, the segmentation process may encounter discrepancies in feature matching. Such discrepancies could lead to diminished performance in iris recognition within the domain of biometrics. Consequently, it is imperative to establish more optimal image sizes. Regarding the neutrosophic block parameter, both the structural representation of the objects and the duration required for segmentation may fluctuate as a function of this parameter. When a substantial number of values are designated, the computational complexity associated with segmentation may decrease; however, the identification of object structures for segmentation becomes increasingly intricate with a higher quantity of neutrosophic blocks. Within the segmentation framework, a critical parameter is the number of classes intended for image segmentation, which is essential for multi-class segmentation endeavors. The segregation of image objects is contingent upon these specified values. \(\sigma\) represents the experimental parameter utilized in the implementation of the proposed segmentation method. The efficacy of the proposed method was assessed through various noise values. For the purposes of evaluation, the proposal exclusively considers the \(\sigma\) parameter. Analysis of sample images indicates that the proposed method is viable across a wide spectrum of noise values. This parameter analysis is instrumental in determining appropriate noise values and facilitating the segmentation process. Based on prior research, machine learning metrics have been utilized to substantiate the proposed methodology. Metrics such as Jaccard, mIoU, precision, recall, F1 score, and accuracy have been incorporated for the validation of segmentation performance. The parameter values are taken randomly then analysis results by hit and trail method then we fix the values to the parameter. From the previous analysis, we obtained the necessary parameters to implement semantic segmentation for the Iris dataset. The proposal conducts an analysis on the training and testing datasets, comprising 108 iris images, each representing an observation. The data is split with a \(70\%\) ratio using a random seed of 29. The standard parameter \(\mathbb {R}^{2}\) is found to be 64 based on the analysis, and the Gaussian standard deviation is set to \(\sigma = 10\) for variation intervals. To improve the segmentation process, we consider h and k as variable parameters. For h values of seven and nine, we examine their impact, while for k values of three and four, we analyze the segmentation parameter. Simultaneously, the observation calculates the segmentation duration for each attribute. The segmentation results for the CASIA dataset are presented in Table 5, where the dataset achieves a cumulative significance score of approximately \(85\%\), considering a mixture of Gaussian and Poisson noises. The \(h=9\) setting outperforms \(h=7\) in terms of both segmentation duration and score for the three-class segmentation. Increasing the block size leads to shorter segmentation times.

After careful verification, we conclude that \(h=9\) is the better neutrosophic block for three-class segmentation of the iris image, yielding an expected score of around \(85\%\) with a \(0.9\%\) error rate. In the case of four-class segmentation, the performance is also significant, with a required minimum grade just above \(84\%\). The Table 6 presented in the research showcases a detailed analysis of the performances exhibited by the proposed method in comparison to various other model segmentation methods that have been developed sequentially. Upon careful examination of the results depicted in the table, it becomes evident that the \(\mathscr {T}_{1k}\) method, in particular, displays notable enhancements in the process of segmentation specifically tailored for iris images. This observation underscores the efficacy and potential superiority of the \(\mathscr {T}_{1k}\) method in addressing the intricacies associated with iris image segmentation, thus offering promising prospects for further advancements in this field. The results reveal an inverse relationship between segmentation class and performance score and duration. Moreover, the neutrosophic block shows an inverse proportionality to segmentation time, where increasing the block size reduces the duration. Using appropriate parameters, we analyzed the CASIA iris dataset for multi class segmentation, achieving good segmentation accuracy. Table 6 thoroughly delineates a comparative analysis of the performance metrics associated with various segmentation methodologies, juxtaposed against the established segmentation techniques currently in use. While numerous studies demonstrate commendable levels of segmentation scores, it is particularly noteworthy that the research endeavors labeled articles22,23,24,25 have not specifically proposed methodologies tailored for the CASIA iris image dataset, thereby indicating a significant gap in the literature. Our primary research objective is to undertake a comprehensive multi-class segmentation initiative pertaining to iris image datasets, which will facilitate a more nuanced understanding of the segmentation process. Furthermore, when examining the general real-time dataset, the column representing mIoU/Accuracy reveals a concerning low performance level regarding the segmentation efficacy of the images analyzed, suggesting potential limitations in the methodologies employed. Additionally, these studies yielded sub optimal performance scores during the data testing phase, which can be attributed to the inadequate training of the model that did not incorporate an appropriate range of performance metrics to ensure robust outcomes. Articles26,27 specifically concentrated on the segmentation of the iris image dataset with an emphasis on achieving multi-class segmentation, contributing valuable insights into this niche area of research. These particular works did manage to achieve commendable performance scores in their attempts to segment the iris image dataset. However, they ultimately fell short in conducting a thorough validation of their proposed methodologies when applied to the testing data, which is a critical aspect of validating research findings. The mIoU/Accuracy metrics presented in Table 6 serve to elucidate the maximum accuracy levels attained by their proposed methodologies, which are of direct relevance to the dataset that aligns with our research objectives. Their research achieved an impressive maximum accuracy rate of 99.05% concerning the multi-class segmentation of CASIA iris images, a noteworthy accomplishment within this domain. In contrast, through the implementation of our proposed \(\mathscr {T}_{1k}\) segmentation method, we successfully enhanced the performance metrics, elevating the maximum accuracy to 99.21%, while also ensuring that our proposed method underwent rigorous validation against the iris image dataset as reflected in the test score column. For the validation process, we achieved an accuracy rate of 84.8% concerning our targeted iris images within the CASIA dataset, providing a solid foundation for our research endeavors. These findings have potential benefits in the area of iris recognition.

From an extensive review of existing literary works and a thorough competitive analysis of various methodologies, it can be conclusively stated that our proposed method yields a marginal enhancement in performance by precisely examining the intricacies of neutrosophic components. In contrast, alternative methodologies have managed to achieve a commendable accuracy rate of 99% exclusively through the utilization of a singular feature pertaining to intensities; however, our proposed method further delves into a comprehensive three-way analysis, which not only enriches the evaluative framework but also facilitates significant advancements in the segmentation process. It is important to acknowledge that the sole minor limitation associated with the proposed method lies in its temporal demands, as it necessitates a block-wise analytical approach to the entirety of the image, which is conducted through the consideration of three distinct membership components. Nevertheless, by concentrating on enhancing performance through a more expansive feature analysis, it can be argued that the proposed method emerges as the most optimal choice for achieving superior segmentation outcomes.

Conclusion

In this article, we suggest a novel approach for neutrosophic sets with semantic segmentation. The intensity values of the membership functions were used to process the segmentation. Since it employs a three-way membership analysis, the segmentation’s effectiveness might be more precise. The article takes CASIA iris image segmentation into consideration for initial implementation.

The proposed \(\mathscr {T}_{1k}\) segmentation methodology was initially executed by utilizing datasets comprised of iris images, which serve as a foundational step in our analytical approach. In examining the existing literature surrounding this topic, it becomes apparent that the CASIA iris image datasets are widely acknowledged within the academic community and offer substantial advantages for researchers who seek to leverage these datasets for their investigative purposes. From the dataset that has been collected, the images are thoroughly extracted and subsequently read by the analytical system, thus paving the way for advanced image processing and analytical evaluations. To commence our image processing journey, we first employed a fundamental technique for resizing images, which is essential for the normalization of the dimensions across the various images working with. Following this initial step, we proceeded to extract neutrosophic features from the intensity values present within the images, thereby enriching our dataset with crucial components for further analytical scrutiny. At this juncture, the processed images now encompass three distinct neutrosophic components, which are vital for the ensuing stages of our analysis. Given that the segmentation technique necessitates the determination of variation values concerning the intensity levels, as dictated by the proposals surrounding indeterminacy functions, it is imperative to compute these variation intensities accurately. Based on the calculated intensities, we then systematically assign labels to the images, which correspond to the number of class segments identified within the dataset. This meticulous approach to training the dataset was executed in this structured manner and subsequently validated through the application of testing data designed for this purpose.

This proposal used Gaussian and Poisson noise models to analyze the segmentation. Numerous segmentation parameters, including \(\mathbb {R}^{2}, h, k,\) and \(\sigma\), were analyzed. This analysis directs us to the task of selection. This attribute evaluation will enable us to enhance the segmentation results for the iris image. With the help of the analysis, we improve accuracy to \(85\%\). This score was attained in the quickest possible time. We assert that it would be the best model for the iris recognition task based on the performance evaluations.

In this manner, the authors accomplished the primary goal articulated in this proposal, which was to convincingly demonstrate that the implementation of image segmentation techniques for multi-class segmentation can indeed be effectively executed through the utilization of neutrosophic sets, a concept that provides a framework for dealing with uncertainty and vagueness in data. The results derived from their comprehensive analysis and experimentation indicate that the method proposed by the authors yields highly effective and reliable outcomes for segmentation tasks, thus validating the efficacy of the approach. The contributions made by the authors in this scholarly paper are not only significant but also hold substantial importance, as they will undoubtedly serve as a valuable resource for the image processing and computer vision community, fostering further advancements and innovations in these interrelated fields.

This research successfully substantiates the feasibility and practicality of employing neutrosophic sets as a robust mechanism for achieving multi-class image segmentation, thereby fulfilling the primary objective that the authors had initially established at the onset of their study. The results derived from their rigorous experimentation and analysis indicate that the method proposed not only delivers effective segmentation results but also contributes in a meaningful way to the evolving domains of image processing and computer vision, highlighting the relevance and applicability of their findings. Furthermore, these results underscore the potential of neutrosophic sets to serve as an invaluable tool for enhancing and refining segmentation techniques, thereby opening up promising avenues for subsequent exploration and application within the academic community. This, in turn, paves the way for researchers to build upon these foundational findings, potentially leading to innovative solutions and significant advancements in the methodologies currently employed for image analysis and interpretation.

The proposed method’s extension versions will put a stronger emphasis on raising performance value than the current method does. Work to shorten the duration time while taking practical factors into account. In feature, we will apply the suggested model to a broad range of image databases and biometric systems. Besides on that the another segmentation method to be carry probably it can be \(\mathscr {T}_{2k}\) method. Organizing these segmentation methods will be our main feature work. We must elevate the new concepts or theories we employ to better work because real-world image data is growing daily. The suggested model accurately analyzes the goal of our work in this regard. This encourages us to apply the ideas to more sophisticated models, like neural networks. This theory will present a different perspective on the membership function approach to computer vision. The face image segmentation process includes the feature approach.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences(CASIA) repository http://biometrics.idealtest.org/#/. This open-source dataset was collected by the National Laboratory of Pattern Recognition (NLPR) at the Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CASIA), for the purpose of academic research. Researchers may contact Dr. Asima Razzaque about the dataset.

References

Guo, L., Shi, P., Chen, L., Chen, C. & Ding, W. Pixel and region level information fusion in membership regularized fuzzy clustering for image segmentation. Information Fusion 92, 479–497 (2023).

Yu, Y. et al. Techniques and challenges of image segmentation: A review. Electronics 12, 1199 (2023).

Verma, H., Agrawal, R. & Sharan, A. An improved intuitionistic fuzzy c-means clustering algorithm incorporating local information for brain image segmentation. Applied Soft Computing 46, 543–557 (2016).

Zhang, M., Zhang, L. & Cheng, H.-D. A neutrosophic approach to image segmentation based on watershed method. Signal processing 90, 1510–1517 (2010).

Guo, Y., Cheng, H. & Zhang, Y. A new neutrosophic approach to image denoising. New Mathematics and Natural Computation 5, 653–662 (2009).

Faraji, M. R. & Qi, X. An effective neutrosophic set-based preprocessing method for face recognition. In 2013 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo Workshops (ICMEW), 1–4 (IEEE, 2013).

Vinoth, D. & Ezhilmaran, D. An analysis of global and adaptive thresholding for biometric images based on neutrosophic overset and underset approaches. Symmetry 15, 1102 (2023).

Toderici, G., O’Malley, S. M., Passalis, G., Theoharis, T. & Kakadiaris, I. A. Ethnicity-and gender-based subject retrieval using 3-d face-recognition techniques. International Journal of Computer Vision 89, 382–391 (2010).

Bendale, A., Nigam, A., Prakash, S. & Gupta, P. Iris segmentation using improved hough transform. In Emerging Intelligent Computing Technology and Applications: 8th International Conference, ICIC 2012, Huangshan, China, July 25-29, 2012. Proceedings 8, 408–415 (Springer, 2012).

Proença, H. & Alexandre, L. A. Iris recognition: Analysis of the error rates regarding the accuracy of the segmentation stage. Image and vision computing 28, 202–206 (2010).

Mahlouji, M. & Noruzi, A. Human iris segmentation for iris recognition in unconstrained environments. International Journal of Computer Science Issues (IJCSI) 9, 149 (2012).

AlShemmary, E. et al. Towards accurate pupil detection based on morphology and hough transform. Baghdad Science Journal 17, 0583–0583 (2020).

Chen, L., Chen, C. P. & Lu, M. A multiple-kernel fuzzy c-means algorithm for image segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B (Cybernetics) 41, 1263–1274 (2011).

Grewal, R., Kasana, S. S. & Kasana, G. Hyperspectral image segmentation: a comprehensive survey. Multimedia Tools and Applications 82, 20819–20872 (2023).

Bezdek, J. C., Hall, L. & Clarke, L. Review of mr image segmentation techniques using pattern recognition. Medical physics 20, 1033–1048 (1993).

Smarandache, F. Neutrosophy: neutrosophic probability, set, and logic: analytic synthesis and synthetic analysis (American Press, 1998).

Sengur, A. & Guo, Y. Color texture image segmentation based on neutrosophic set and wavelet transformation. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 115, 1134–1144 (2011).

Nishino, K. & Nayar, S. K. Corneal imaging system: Environment from eyes. International Journal of Computer Vision 70, 23–40 (2006).

El-Shahat, D., Talal, N., Ye, J. & Cui, W.-H. Ct image segmentation using optimization techniques under neutrosophic domain. Neutrosophic Systems with Applications 16, 1–11 (2024).

Abdulbaqi, A. S. et al. Efforts of neutrosophic logic in medical image processing and analysis. International Journal of Neutrosophic Science (IJNS) 24 (2024).

Ghanbari Talouki, A., Koochari, A. & Edalatpanah, S. A. Video completion in the presence of moving subjects based on segmentation using neutrosophic sets. Big Data and Computing Visions 5, 1–10 (2025).

Long, J., Shelhamer, E. & Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 3431–3440 (2015).

Cosmin Duta, I., Liu, L., Zhu, F. & Shao, L. Pyramidal convolution: Rethinking convolutional neural networks for visual recognition. arXiv e-prints arXiv–2006 (2020).

He, X. et al. Location-aware upsampling for semantic segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.05250 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 10012–10022 (2021).

Kerrigan, D., Trokielewicz, M., Czajka, A. & Bowyer, K. W. Iris recognition with image segmentation employing retrained off-the-shelf deep neural networks. In 2019 International Conference on Biometrics (ICB), 1–7 (IEEE, 2019).

Chen, Y., Wang, W., Zeng, Z. & Wang, Y. An adaptive cnns technology for robust iris segmentation. IEEE Access 7, 64517–64532 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the editors and reviewers of this journal for their insightful feedback and constructive comments. Their valuable suggestions greatly enhanced the quality of this research, and their time and effort are deeply appreciated. We are also thankful to the editorial team for their professionalism and support throughout the review process. Their commitment to advancing scholarly research is commendable, and we are grateful for their contributions to the success of this publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and ScientificResearch, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [KFU250131].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, Vinoth D. and Ezhilmaran D; formal analysis, investigation, Asima Razzaque.; visualization, Vinoth D and Saima Noor; supervision, project administration, Ezhilmaran D and Asima Razzaque; funding acquisition, Asima Razzaque.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dhatchinamoorthy, V., Devarasan, E., Razzaque, A. et al. A study on neutrosophic \(\mathscr {T}_{\textrm{1k}}\)-semantic segmentation for iris image recognition with Gaussian and Poisson noises. Sci Rep 15, 13699 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93743-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93743-6