Abstract

Smokeless tobacco (ST) products create a deadly combination of addiction to nicotine and exposure to toxic substances. Nass is the predominant smokeless tobacco (ST) product consumed in Iran. This study was conducted to evaluate the levels of arsenic (As), lead (Pb), nickel (Ni), and cadmium (Cd) in Nass brands available in the Iranian market. A total of 42 samples were analyzed for the levels of heavy metals using flame atomic absorption spectrometry. The study also evaluated the risk associated with carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic toxic metal contamination in smokeless tobacco in Iran. The level of heavy metals measured in various Nass samples was ranked as Pb > Ni > Cd > As .The mean levels (range) of Pb, Cd, As, and Ni in Nass samples were determined to be 38.71 µg/g (17.60–57.70), 2.90 µg/g (1.20–3.65), 0.71 µg/g (0.25–1.17), and 23.24 µg/g (4.95–44.65), respectively. The levels of Pb, Cd, As and Ni in handmade samples are higher than products manufactured at the plant. The levels of Pb, Cd and Ni in all samples were higher than the Swedish Match recommended limits. While the levels of As in 12% of samples were lower than the standard defined by the Swedish Match. The Estimated daily intake (EDI) values for As, Cd, Ni and Pb are below the reference dose (RfD) established by the Environmental Protection Agency. The findings indicate that the target hazard quotient (THQ) and the hazard index (HI) values in the study were below 1. In this study, for the first time demonstrated that Nass consumers in Iran are at risk of exposure to Pb, As, Cd, and Ni. Consequently, the health system should prioritize raising public awareness about the health risks associated to Nass.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The term “smokeless tobacco” covers a wide and highly varied array of products that exhibit differences in color, appearance, texture, packaging, and methods of consumption. In fact, ST refers to a variety of products containing tobacco as its main ingredient that is consumed without burning, such as chewing, sucking, and sniffing tobacco1.The use of ST products is a major public health challenge. Globally, more than 350 million people use ST products and the highest rates of consumption were in South-East Asia Region2. According to the INTERHEART study conducted in 52 countries, 204,309 people died in 2010 from coronary heart disease attributed to the use of ST3. A 2004 review of epidemiological and laboratory studies by the International Agency for Cancer Research (IARC) found that there is sufficient evidence linking smokeless tobacco to oral cancer, esophageal cancer, and pancreatic cancer in humans4. In 2017, at least 2.5 million disability adjusted life years (DALYs) and more than 90,000 lives were lost worldwide due to cancers of the mouth, throat and esophagus that can be attributed to ST use5.

Users of ST receive various levels of hazardous substances in their bodies through chewing, sucking and inhaling. These dangerous substances can exhibit significant toxicity even in small quantities6. More than 30 known carcinogens have been detected in ST products, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, nitrosamines, formaldehyde, acrolein and heavy metals2. Heavy metals are a general term referring to the group of metals and metalloids with an atomic density greater than 4000 kg/m37. Approximately twenty chemical elements are recognized as essential for various physiological functions in the human body. Therefore, most known metals (metalloids) are non-essential to humans, and even those considered as essential can become harmful when present in excessive amounts8. In fact, consumption or environmental exposure to metal ions can create a paradoxical situation. That is, in very low doses of essential elements, there is a significant level of side effects that decrease with an increase in the dose. Conversely, when the dose rises to very high levels, a toxic response appears9. Mercury (Hg), Pb, Ni, Cd and As are among the most common toxic metals that the exposure of human societies with them has increased dramatically in recent decades10. They can disrupt important biochemical processes and pose an important risk to the health of humans, plants and animals. Environmental exposure to heavy metals has long been linked to an increased incidence of anemia, hypertension, and diabetes. It is also associated with reduced intelligence quotient in children, as well as higher mortality rates from malignant neoplasms and nephritis11,12. According to the latest WHO report in 2024, Pb exposure was responsible for over 1.5 million deaths worldwide in 2021, primarily due to cardiovascular effects. Furthermore, in the same year, Pb exposure contributed to more than 33 million DALYs lost globally, reflecting the significant impact on both mortality and long-term disability13.Hence, international organizations have established guidelines to minimize the hazards associated with exposure to some of the toxic metals14,15.

Nass (or Naswar) is a type of ST product usually used in Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan4. Although there is no detailed study of the number of Nass consumers in the general population of Iran, the Gulistan cohort survey (more than 50,000 participants) estimated that this number is above 6%16. Additionally, study results indicate that the prevalence of ST use among Iranian students varies by geographical region, ranging from 11 to 45.7%17. Nass is a mixture of tobacco leaf powder (Nicotina rustica), ash, either cotton or sesame oil and slacked lime18. In some areas, flavoring agents (e.g. cardamom, menthol) and coloring agents (e.g. indigo) are incorporated into the final product. Nass is prepared by adding water to a cement-lined cavity, followed by the addition of lime and then tobacco. Ash and other agents are then added and the mixture is rolled into balls19. Nass is usually placed under the tongue and slowly sucked for 15 to 30 min and then discarded4. Numerous scientific studies have assessed the level of heavy metals in Nass and other ST products commonly available in the market of different countries20,21,22,23, but no studies have been published on the levels of heavy metals in Nass samples in Iran. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess levels of Cd, Pb, As and Ni in Nass samples available in the Iranian market.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

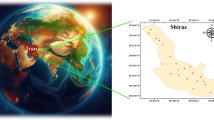

The use of Nass is more prevalent in the southeastern regions of Iran compared to other parts of the country. This is primarily because these regions border Pakistan and Afghanistan, making these products more accessible to the population of these regions. In this spring 2023, a total of 42 Nass samples were randomly purchased from shops in the cities of Kerman and Rafsanjan in southeastern Iran. The specimens were transported to the laboratory following acquisition and stored at a refrigerated temperature until analysis. The samples collected were classified according to their color (green or light brown) and packaging method (factory packaged or hand packaged). The Nass products that were packaged in the factory are actually samples weighing 10 to 20 gr (gram), distributed in the market with different brand names. The brand names have been kept confidential in this document to adhere to legal requirements. In contrast, handmade Nass refers to small packages containing 10 to 20 g of Nass that are produced in local workshops.

Sample preparation and statistical analysis

Prior to analysis, the Nass samples were dehydrated in the dry heat oven (Nuve FN 400) at a temperature of 105 °C for a duration of 2 h. Then the samples were completely ground and 1 gr of it was ashed at a temperature of 650 °C for approximately 40 min. The remaining ash was dissolved in 12 mL of the HNO3/HClO4 mixture in a 3:1 volume ratio and filtered through Whatman filter paper (No. 42). Finally, the solution was mixed with deionized water in a volumetric flask until it reached a total volume of 24 mL. The level of Cd, Pb, As and Ni was measured using the ChemTech flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer (FAAS) model CTA 3000 (United Kingdom). Pb Cd, Ni and As hollow cathode lamps, operated at 5.0 mA, were used as the radiation sources. The analytical wavelengths (217.0 nm for Pb and 193.7 nm for As) and slit width (0.4 nm for Pb and 0.2 nm for As) were set as recommended by the manufacturers. Measurements were conducted at 228.8 nm and 232.0 nm, using spectral bandwidths of 0.4 nm and 0.2 nm for Cd and Ni, respectively15,24. The details of the instrument and the parameters for measuring Cd, Pb, As and Ni are reported in Table 1. The previously described hydride method was used to estimate the quantity of As15. Samples were analyzed in triplicate to ensure precision and reduce any potential errors in the experiment. The accuracy of measurements was examined by adding standard solutions of Pb (0.1, 0.5, 1.0 µg/g), Cd (0.01, 0.05, 0.01 µg/g), As (0.01, 0.05, 0.01 µg/g), and Ni (0.1, 0.5, 1.0 µg/g) to 3 Nass samples. The recovery value of Pb, Cd, As and Ni in Nass samples were between 92.5% and 104% (Table 1). The statistical analysis were performed using SPSS version 16 (SPSS, Inc. in Chicago, IL). The data was presented as the average value ± standard deviation (SD). Independent t-test was used to compare the mean levels of metals in different groups. Differences in means were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Estimated daily intake (EDI)

The following equation was utilized to calculate the EDI of Pb, Cd, As and Ni.

Where C is the level (µg/g) of Pb, Cd, As and Ni in Nass samples; Abs is the gastrointestinal (GI) absorption rate of the metal (Pb, As, Cd, Ni, ) from Nass. Abs can have a range from less than 0.01 (< 1%) to 1.0 (100%). In evaluating the potential risk, it is assumed that the bioavailability of the toxic substance in ST is 100% under ideal conditions. Considering that Nass users typically spit it out 15 to 30 min after using, we assumed that the absorption rate of Pb, Cd, As and Ni from Nass was less than 100%. To our knowledge, no research has specifically examined the GI bioavailability of As, Pb, Cd, and Ni from ST. Nevertheless, a previous study showed that 18–24% of As, 45–75% of Cd, 30–55% of Ni, and 20–30% of Pb found in different types of SLT products can be released into an artificial saliva extracts25. In this study, the maximum values of Abs of 0.24, 0.75, 0.55, and 0.3 were used for risk assessment of exposure to As, Cd, Ni and Pb, respectively. DNI is the amount of daily Nass intake by the consumers (10 gr/day); Ef is exposure frequency (365 day/year); Ed is the duration of exposure to a metal through Nass ingestion (assuming 50 years in this study); BW is the consumer body weight and T represents the averaging exposure time (days) to toxic metals and it is estimated as Ef × Ed. The average body weight of Iranian men and women was 79.6 and 70 kg, respectively26.

Non-carcinogenic effects

The hazard index (HI) assesses the cumulative effect of simultaneous exposure to Pb, Cd, As, and Ni through the consumption of Nass. If HI > 1, there is a potential risk of non-carcinogenic health effects from Nass consumption. The equation for HI is as follows.

The target hazard quotient (THQ) represents the non-carcinogenic health risk associated with exposure to the specific toxic substance. If THQ < 1, non-carcinogenic health effects are not expected. However, if THQ > 1, there is a likelihood that the individual may experience health side effects.

Here, the oral RfD (reference dose) is the maximum daily exposure dose to a toxic metal (Pb, Cd, Ni, and As) where no non-cancer health effects are expected. The RfD values reported by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for As, Cd, and Ni are 0.3, 1, and 20 µg/ kg body weight /day, respectively27,28,29. However, the risk assessment for Pb is unique because a RfD value for Pb has not been established by the EPA30. Therefore, we utilized the provisional tolerable weekly intake (PTWI) values recommended by the World Health Organization to obtain the RfD for Pb (25 µg/kg body weight/week)31. Consequently, we considered the value of 3.57 µg/kg/day as the RfD for Pb in this study.

Carcinogenic risk (CR)

The CR represents the likelihood of an individual developing cancer over their lifetime due to exposure to a potential carcinogen. The CR is calculated using the following equation.

Where slope factor (SF) refers to the carcinogenic risk for a potentially carcinogenic substance. The EPA has reported an oral SF value of 1.5 mg/kg/day for As27. However, this organization has not provided oral SF values for Pb, Cd, and Ni28,29,30. The CR values ranging from 0.0001 to 0.000001 indicate that the carcinogenic risk from Nass consumption is considered acceptable or tolerable, while values below this range suggest that compound consumption is significantly safe32.

Results

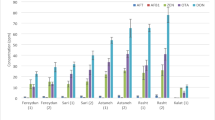

The average levels of Pb, Cd, As, and Ni in 42 Nass samples are reported in Table 2. All Nass samples had levels of Pb, Cd, and Ni that exceeded the LOQ, while 34 (81%) of the samples had As levels above the LOQ (Table 1). The level of heavy metals measured in various Nass samples was ranked as Pb > Ni > Cd > As. The minimum and maximum levels of Pb, Cd, As, and Ni in 42 Nass samples were 17.60–57.70 µg/g, 1.20–3.65 µg/g, 0.025–0.117 µg/g, and 4.95–44.65 µg/g, respectively. The mean ± SD levels of Pb, Cd, As, and Ni in the samples of Nass were 38.71 ± 8.05 µg/g, 2.90 ± 0.55 µg/g, 0.071 ± 0.025 µg/g and 23.24 ± 7.36 µg/g, respectively. The analysis of metal levels in Nass samples based on the color and type of packaging is presented in Table 2. The levels of Pb and As in brown samples was higher than in green Nass, whereas the Cd and Ni levels in green samples were higher. The variation in metal levels among different groups based on color type was not found to be significant. The current study’s findings reveal that the level of the 4 metals studied is higher in hand packed samples compared to factory packed Nass samples. This observed difference was statistically significant only for Cd metal (P = 0.005). The levels of metals in the soil where tobacco is grown seem to significantly influence the variations in metal content across different Nass varieties. In fact, the uptake and accumulation of metals by plants are influenced by the physicochemical properties of the soil (e.g., organic matter, cation exchange capacity, redox potential, and pH) as well as the timing of harvest15. According to Table 3, a total of 10 Nass brands (30 samples) was analyzed for the level of metals. Brands number 7, 6, 8, and 10 had the highest levels of Pb (50.77 µg/g), Cd (3.25 µg/g), As (0.089 µg/g), and Ni (33.75 µg/g).

In order to minimize the risks associated with exposure to ST, some countries have established limits on the maximum allowable levels (MAL) of toxic metals. Swedish Match has released guidelines for MAL of tobacco-specific nitrosamines, metals and trace elements in snus (a moist form of ST), collectively referred to as the GothiaTek® standard. The MAL for Pb, Cd, As and Ni in the Swedish snus according to the GothiaTek® standard were 1 µg/g, 0.5 µg/g, 0.25 µg/g and 2.25 µg/g, respectively33. In the present study, the levels of Pb, Cd and Ni in all samples were higher than the Swedish Match recommended limits. While the levels of As in 12% of samples were lower than the standard defined by the Swedish Match. This could suggest potential health risks for consumers using Nass. Fortunately, the EDI values of Pb, Cd, As, and Ni for both Iranian men and women were below the RfD recommended by the EPA (Table 4). The information presented in Table 4 indicates that the health risk (Non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic) resulting from exposure to Pb, As, Cd, and Ni through the consumption of Nass by Iranian consumers is negligible. Given the potential carcinogenic effects linked to certain elements, the CR associated with As is outlined in Table 4. In men and women the CR values of As was 0.000032 and 0.000036, respectively. A CR of less than 1 × 10− 4 is considered as acceptable level for regulatory purposes.

Discussion

Because international tobacco control efforts have primarily targeted cigarettes, health risks related to ST products have received little attention from researchers and policymakers. In this research, we present the levels of Pb, As, Ni, and Cd in Nass samples from Iran, along with an assessment of the health risks. The findings of the current study indicate that Cd, Pb, and Ni were detected in all samples and 81% of samples exhibited As levels exceeding the LOQ (0.005 µg/g). In recent years, there has been a growing concern regarding public health issues related to heavy metals. While heavy metals are naturally present in the Earth’s crust, Human exposure to these substances can occur through the inhalation of airborne dust or the ingestion of water, soil, and food chain11,34,35. Most of heavy metals can be dangerous to organisms, even those that play a pivotal role in various biochemical and physiological mechanisms of organisms. It has been reported that metals such as Pb, As, Cd and Ni are considered as non-essential metals and have no recognized physiological functions in the human body36. The findings of the current study indicate that individuals who consume Nass in Iran are exposed to various levels of toxic metals, specifically Pb, Cd, and Ni.

Pb levels in Nass samples

Pb is a toxic metal whose extensive use has caused considerable public health issues in various regions of the world. Pb is an extremely toxic metal that impacts nearly every organ in the body. Prolonged exposure to lead has been linked to the development of anemia, elevated blood pressure, chronic kidney insufficiency, impairment of central nervous system function and damage to the reproductive systems of both males and females37. The nervous system is the most significantly impacted by Pb toxicity in both children and adults38. Exposure to lead can negatively impact children’s intelligence quotient (IQ) and their educational achievement39,40. In the general population, Pb exposure primarily occurs via food, water, air, and soil37,41. Furthermore, plants such as tobacco are also an important source of Pb and Cd exposure42. The mean levels of Pb found in this study were 38.71 µg/g with a range of 17.60–57.70 µg/g and the levels of Pb in all samples were higher than the GothiaTek® standard (1 µg/g). The findings of the current study are comparable to those conducted in other countries. In Pakistan, the average Pb level in 30 naswar brands is reported to be 21.05 µg/g (range of 12.4–111.15 µg/g) and the levels of Pb in all samples were higher than the GothiaTek® standard21. In addition, in other countries such as Nigeria23, Bangladesh20, Saudi Arabia43 and Indian44 the Pb content in ST products has been demonstrated to range from 0.01 to 2.48 µg/g, 0.99 to 10.02 µg/g, < LOD – 26.2 µg/g, and 0.03 to 33.3 µg/g, respectively. Additionally, the mean Pb level found in the ST samples of this study was higher than the reported levels in United Kingdom (UK)45, United States (US)46,47, and Oman48. In addition, The results of studies conducted in the US indicated that the Pb levels in the 100% samples examined were below the maximum permissible levels established by GothiaTek®46,47.

Cd levels in Nass samples

The kidneys and liver are two vital organs significantly affected by long-term exposure to cadmium. The accumulation of cadmium in the kidneys can impair normal kidney function, leading to increased excretion of low molecular weight proteins in the urine49,50. In recent decades the increase in the presence of Cd in the environment is mainly the result of its widespread use in the development of modern industries and technologies. Human exposure to Cd primarily occurs through the consumption of contaminated foods. As a result, elevated levels of Cd have been detected in plant-based foods (notably rice, wheat, leafy green vegetables, and potatoes), seafood (including crustaceans, bivalve mollusks, oysters, cephalopods, and crabs), as well as animal products (such as liver and kidneys)51. Another source of Cd exposure for the general population is tobacco consumption. The findings of the studies indicate a significant increase in serum and urinary Cd levels among smokers in comparison to non-smokers52. The findings of the current study indicate that individuals who use Nass are subjected to Cd exposure. The mean levels of Cd found in this study were 2.90 µg/g with a range of 1.20–3.65 µg/g and the levels of Cd in all samples were higher than the GothiaTek® standard (0.5 µg/g). The results of the present study are consistent with those obtained in research conducted in other countries. In Pakistan, the overall mean of Cd level in naswar samples was 2.34 ug/g with a range of 0.25–9.2 µg/g and Cd levels in 25 out of 30 samples (83%) were higher than the GothiaTek® standard21. Additionally, similar Cd levels were observed in ST samples from Bangladesh, ranging from 1.05 to 3.53 µg/g and the levels of Cd in all samples were higher than the GothiaTek® limit20. However, the levels of Cd contamination in Iranian ST were found to be higher than those in Nigeria (ranging from 0.01 to 0.17 µg/g)23, Indian (ranging from 0.01 to 3.1 µg/g)44, Oman (ranging from 1.75 to 1.95 µg/g)48. In addition, the Cd levels in the 100% of ST samples examined in Nigeria were below the MAL established by GothiaTek®23.

As levels in Nass samples

Over 200 million people worldwide are potentially exposed to high levels of arsenic, mainly from Asia and Latin America. Arsenic exposure has been associated with the development of non-communicable diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular issues, skin conditions, neurological disorders, and various forms of cancer53,54. Arsenic is a natural element that is commonly found in the Earth’s crust. The primary source of As exposure is contaminated drinking water. It is also present in air, food, soil, and tobacco41,55. The findings of the current study indicate that individuals who use Nass are exposed to relatively low levels of As. The mean levels of As found in this study were 0.71 µg/g with a range from less than 0.005 to 1.17 µg/g. Furthermore, the levels of As in 88% of samples were higher than the MAL defined by the GothiaTek® (0.25 µg/g). In Pakistan, As levels in the Naswar samples studied were in the range of 0.15–14.04 µg/g with an mean of 1.25 µg/g and As levels in 28 out of 30 samples (93.3%) were higher than the GothiaTek® standard21. In addition, in other countries such as UK45, Indian44 and Saudi Arabia43 the As content in ST products has been demonstrated to range from 0.04 to 0.46 µg/g, 0.11 to 3.5 µg/g, and 0.2–7.2 µg/g, respectively.

Ni levels in Nass samples

Ni is a metal commonly found throughout the environment. The highest levels of Ni compounds in the air result from the burning of fossil fuels. Additionally, direct leaching from rocks and sediments leads to elevated level of Ni in water56. There is evidence that nickel may be an essential trace element for mammals. However, despite its presence in very low levels (0.5 nM) in human blood, no identified need for nickel or nickel-dependent enzymes has been found in mammals57. Exposure to nickel in humans can lead to respiratory issues, cardiovascular diseases, kidney problems, and allergic dermatitis56,58. Nonetheless, the most significant concern is its carcinogenic potential, as certain nickel compounds have been classified as Group 1 carcinogens for humans by the IARC57. Human exposure to Ni primarily occurs through ingestion via water and food. Moreover, inhalation is a significant route of Ni exposure for humans in workplace settings. Combustion of fossil fuels, the incineration of waste, using cheap jewelry, Kitchen utensils, and tobacco smoking are other environmental sources of Ni exposure. Research shows that each cigarette contains between 1.1 and 3.1 µg of Ni56. The findings of the current study indicate that individuals who use Nass are exposed to relatively high levels of Ni. The mean levels of Ni found in this study were 23.24 µg/g with a range from less than 4.95 to 44.65 µg/g. Furthermore, the levels of Ni in 100% of samples were higher than the MAL defined by the GothiaTek® (2.25 µg/g). The results of the present study are consistent with those obtained in research conducted in other countries. In Saudi Arabia, the mean Ni level in thirty-three ST products (Shamma) was recorded at 40.06 µg/g (range of 0.6–267 µg/g)43. In Pakistan, the mean levels of Ni found in thirty ST samples (Naswar) was 12.2 µg/g with a range from 2.2 to 64.8 µg/g. Moreover, level of Ni in 93.3% of samples were higher than the GothiaTek® standard21. In other countries such as Nigeria23, UK45, Indian44 and USA46 the Ni content in ST products has been demonstrated to range from 0.2 to 0.7 µg/g, 1.22 to 5.88 µg/g, 1.3 to 13.05 µg/g, and 0.65–7.54 µg/g, respectively.

As compared above, it seems that the levels of Cd, Pb, As, and Ni in the ST samples analyzed in this study is higher than those reported in the Oman, India, US, UK, and Nigeria. While the levels of metal toxins found in this study was close to findings from research conducted on Shamma samples in Saudi Arabia43 and Naswar samples in Pakistan21.The ST Products can be used individually or in combination with substances like ash, lime, oil, flavouring agents (e.g. cardamom, menthol) and colouring agents (indigo), which can increase the level of toxic metals in the final product19. In the production of ST products such as Nass, Naswar, Shammah, Zarda, Maras, Chimo, Iq’mik and Khaini used tobacco in combination with lime and ash. In contrast, the tobacco is used alone in the production of ST products including dry snuff, moist snuff, Gudhaku, Gul, Khiwam, Loose-leaf, Mishri, Plug, Toombak, Red tooth powder, Tuibur, Twist and Roll, which mainly used in European and American countries and regions19. In addition, the level of toxic metals in ST products can be influenced by the species of tobacco used, the conditions under which the plants grown (such as soil metal levels), the method of tobacco processing (fermentation versus pasteurization), and the conditions for storing the product4. It seems that the variation in toxic metal levels found in ST products across different studies may be attributed to differences in measurement techniques.

Overall, the findings of this survey indicate that the levels of Pb, Cd, As and Ni in handmade samples are higher than products manufactured at the plant. Additionally, the difference in Cd levels was statistically significant. The variations in metal content within the analyzed Nass samples, based on their color, do not exhibit a consistent pattern. Both commercial and domestic Nass are widely used throughout Iran, and household products are more popular. Although the consumption of Nass is not prohibited in Iran, all factory products of Nass found in the Iranian market is obtained through smuggling activities from neighboring countries, particularly Pakistan and Afghanistan. While the production of handmade Nass is domestic in Iran. These products do not have packaging that displays the brand name or product description, making it difficult to monitor the health production process. Therefore, the levels of metals in household products are expected to be higher than those in factory-produced products.

Risk assessment

It is widely recognized that prolonged use of ST is associated with an increased risk of cancer. A review conducted by the IARC in 2004 concluded that there is sufficient evidence from epidemiological and laboratory studies to establish that ST causes oral, esophageal, and pancreatic cancers in humans19. Estimates indicate that individuals who consume Nass are 10 times more likely to develop oral cancer compared to those who do not use it59. According to EPA standards regarding non-carcinogenic risk, if the THQ and Hi is less than 1, the chemical substance poses no threat to individual health in lifetime. Similarly, an estimated CR between 0.0001 and 0.000001 indicates no carcinogenic risk to individual health in lifetime32. As shown in Table 4, EDI values calculated for Pb, Cd, As and Ni were lower than RfD standards. The findings indicate that the THQ values for all metals examined in the study were below 1, suggesting that there is a negligible health risk from exposure to Pb, Cd, As, and Ni through Nass consumption. The study results also showed a relatively low HI (< 1) in women and men, which indicates a negligible health risk (non-carcinogenic) associated with simultaneous exposure to Pb, Cd, As, and Ni through Nass consumption. It is important to note that the relatively low levels of HI observed in this study are related to only four metal ions. Consequently, it can be assumed that measuring other metal and toxic substances in the Nass could significantly increase HI values. Additionally, The CR value for men and women was less than 0.0001. As a result, exposure to As through Nass consumption can pose a acceptable cancer risk for adult in Iran. In fact, a risk of 0.0001 indicates a probability of 1 chance in 10,000 of an individual developing cancer through exposure to As in Nass32. It is also important to note that when calculating risk assessment, factors such as metal levels in the consumed substance, daily consumption amounts, average body weight of the population, and the duration of metal exposure play a crucial role60. Therefore, even if metal levels exceed the maximum permissible limit set by the GothiaTek®, a decrease in Nass consumption or an increase in body weight could lead to a reduction in the THQ and HI values below one. On the other hand, when assessing human health risks, data obtained from animal studies are primarily used to determine permissible levels of chemicals in products. However, this approach introduces certain complications when adapting animal data for human health risk assessments61. To address these issues, uncertainty factors (UF) are applied when using animal data to establish permissible levels for humans. Specifically, it has been suggested that a permissible level for variety of materials can be derived by dividing the chronic NOAEL (no-observed-adverse-effect level) obtained from animal studies by a UF from 10 to 10062. This method is considered reliable enough to protect the majority of the human population from adverse health effects caused by long-term exposure to a specific chemical. Therefore, the lower THQ and HI values in the present study, despite the higher metal levels compared to the permissible limits set by GothiaTek®, are justified. This is because international institutions and agencies employ a very stringent approach when determining permissible levels of chemicals in products.

Finally, there are limitations in our study that should be considered when interpreting the results. These include the small sample size, the regional focus of the study, and the failure to identify other toxic metals in the analyzed samples. Unlike cigarettes, there is limited standardized data available for health risk assessment and detailed toxicological analysis of smokeless tobacco products. Therefore, the lack of information on the bioavailability of the metals in Nass consumers is a significant limitation when assessing health risks.

Conclusions

The Nass is the most important form of ST product in Iran, and to date, there has been no research conducted on the levels of toxic metals it. The findings of this study indicate that Nass available in the Iranian market has elevated levels of Pb, Cd, Ni, and As. The metal levels detected in nearly all Nass samples from the Iranian market exceeded the permissible limits established by GothiaTek® for ST products. The THQ and HI values in the study were below 1, suggesting that there is a negligible health risk (non-carcinogenic) from exposure to Pb, Cd, As, and Ni through Nass consumption. It is important to note that the relatively low levels of THQ and HI observed in this study are related to only four metal ions in Nass samples. Therefore, this does not rule out long-term health risks from prolonged exposure to, as it is reasonable to assume that measuring other metals and toxic substances in Nass samples could significantly increase the THQ and HI values. In this study, the CR for As was below 1 × 10⁻⁴, which is the threshold acceptable for cancer risk. Due to the presence of various types of carcinogens in the Nass, it is recommended to implement national policies and regulations aimed at lowering the levels of toxic metals and other harmful substances found in ST products available in the Iranian market. This can be achieved by establishing national limits for toxic metal levels in smokeless tobacco products and enhancing public health awareness campaigns. Simultaneously, it is suggested that the design and implementation of ST cessation programs targeting adolescents and young be considered as long-term strategies.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- ST:

-

Smokeless tobacco

- As:

-

Arsenic

- Pb:

-

Lead

- Ni:

-

Nickel

- Cd:

-

Cadmium

- HI:

-

Hazard index

- THQ:

-

Target hazard quotient

- RfD:

-

Reference dose

- EPA:

-

Environmental Protection Agency

- CR:

-

Carcinogenic Risk

- SF:

-

Slope factor

- UF:

-

Uncertainty factors

References

Boffetta, P., Hecht, S., Gray, N., Gupta, P. & Straif, K. Smokeless tobacco and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 9, 667–675 (2008).

Hecht, S. S. & Hatsukami, D. K. Smokeless tobacco and cigarette smoking: chemical mechanisms and cancer prevention. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 22, 143–155 (2022).

Siddiqi, K. et al. Global burden of disease due to smokeless tobacco consumption in adults: analysis of data from 113 countries. BMC Med. 13, 1–22 (2015).

Hatsukami, D., Zeller, M., Gupta, P., Parascandola, M. & Asma, S. Smokeless tobacco and public health: a global perspective. (2014).

Siddiqi, K. et al. Global burden of disease due to smokeless tobacco consumption in adults: an updated analysis of data from 127 countries. BMC Med. 18, 1–22 (2020).

Hoffmann, D. & Djordjevic, M. V. Chemical composition and carcinogenicity of smokeless tobacco. Adv. Dent. Res. 11, 322–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/08959374970110030301 (1997).

Vardhan, K. H., Kumar, P. S. & Panda, R. C. A review on heavy metal pollution, toxicity and remedial measures: current trends and future perspectives. J. Mol. Liq. 290, 111197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111197 (2019).

Zoroddu, M. A. et al. The essential metals for humans: a brief overview. J. Inorg. Biochem. 195, 120–129 (2019).

Shahid, M. et al. Trace elements-induced phytohormesis: a critical review and mechanistic interpretation. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 1984–2015 (2020).

Renu, K. et al. Molecular mechanism of heavy metals (Lead, chromium, arsenic, Mercury, nickel and Cadmium)-induced hepatotoxicity–A review. Chemosphere 271, 129735 (2021).

Rehman, K., Fatima, F., Waheed, I. & Akash, M. S. H. Prevalence of exposure of heavy metals and their impact on health consequences. J. Cell. Biochem. 119, 157–184 (2018).

Yao, X. et al. Stratification of population in NHANES 2009–2014 based on exposure pattern of lead, cadmium, Mercury, and arsenic and their association with cardiovascular, renal and respiratory outcomes. Environ. Int. 149, 106410 (2021).

WHO. Lead poisoning. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lead-poisoning-and-health (2024).

Monchanin, C., Devaud, J. M., Barron, A. B. & Lihoreau, M. Current permissible levels of metal pollutants harm terrestrial invertebrates. Sci. Total Environ. 779, 146398 (2021).

Rezaeian, M., Mohamadi, M., Ahmadinia, H., Mohammadi, H. & Ghaffarian-Bahraman, A. Lead and arsenic contamination in Henna samples marketed in Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 195, 913 (2023).

Pourshams, A. et al. Cohort profile: the Golestan cohort Study—a prospective study of oesophageal cancer in Northern Iran. Int. J. Epidemiol. 39, 52–59 (2010).

Solhi, M. et al. Smokeless tobacco use in Iran: a systematic review. Addict. Health. 12, 225 (2020).

U.S. Department of Health and Human & Services, U. The Health Consequences of Using Smokeless Tobacco: A Report of the Advisory Committee To the Surgeon General. (US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 1986).

Cancer, I. A. f. R. O. Smokeless Tobacco and some Tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. Vol. 89 (World Health Organization, 2007).

Hossain, M. T., Hassi, U. & Huq, S. I. Assessment of concentration and toxicological (Cancer) risk of lead, cadmium and chromium in tobacco products commonly available in Bangladesh. Toxicol. Rep. 5, 897–902 (2018).

Saeed, M. et al. Assessment of potential toxicity of a smokeless tobacco product (naswar) available on the Pakistani market. Tob. Control 21, 396–401 (2012).

Prabhakar, V., Jayakrishnan, G., Nair, S. & Ranganathan, B. Determination of trace metals, moisture, pH and assessment of potential toxicity of selected smokeless tobacco products. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 75, 262 (2013).

Orisakwe, O. E., Igweze, Z. N., Okolo, K. O. & Ajaezi, G. C. Heavy metal hazards of Nigerian smokeless tobacco. Tob. Control 23, 513–517 (2014).

Rezaeian, M. et al. Determination of Mercury, cadmium, and nickel in Henna samples. Environ. Monit. Assess. 197, 248 (2025).

Arain, S. S., Kazi, T. G., Arain, J. B., Afridi, H. I. & Brahman, K. D. Preconcentration of toxic elements in artificial saliva extract of different smokeless tobacco products by dual-cloud point extraction. Microchem. J. 112, 42–49 (2014).

Ghaffarian-Bahraman, A., Mohammadi, S. & Dini, A. Occurrence and risk characterization of aflatoxin M1 in milk samples from southeastern Iran using the margin of exposure approach. Food Sci. Nutr. 11, 7100–7108 (2023).

Agency, U. S. E. P. & Inorganic arsenic. https://iris.epa.gov/static/pdfs/0278_summary.pdf (1991).

Agency, U. S. E. P. & Cadmium. https://iris.epa.gov/static/pdfs/0141_summary.pdf (1989).

Agency, U. S. E. P. Soluble salts of nickel. https://iris.epa.gov/static/pdfs/0271_summary.pdf (1995).

Agency, U. S. E. P. Lead and compounds (inorganic); CASRN 7439-92-1. https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris/iris_documents/documents/subst/0277_summary.pdf#nameddest=rfd (2004).

Organization, W. H. Exposure To Lead: a Major Public Health Concern. Preventing Disease Through Healthy Environments. (World Health Organization, 2023).

Assessment, P. R. Risk assessment guidance for superfund: III-part a. Process. Conducting Probabilistic Risk Assess. Unites States Environ. Prot. Agency Wash. (2001).

Match, S. accessed on 18. 02. GOTHIATEK® limits for undesired components. https://www.swedishmatch.com/Snus-and-health/GOTHIATEK/GOTHIATEK-standard/ (2025).

Maleky, S., Faraji, M., Hashemi, M. & Esfandyari, A. Investigation of groundwater quality indices and health risk assessment of water resources of Jiroft City, Iran, by machine learning algorithms. Appl. Water Sci. 15, 1–22 (2025).

Maleky, S. & Faraji, M. BTEX in ambient air of Zarand, the industrial City in Southeast of Iran: concentration, Spatio-temporal variation and health risk assessment. Bull. Environ Contam. Toxicol. 111, 25 (2023).

Tchounwou, P. B., Yedjou, C. G., Patlolla, A. K. & Sutton, D. J. Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. Molecular, clinical and environmental toxicology: volume 3: environmental toxicology. 133–164 (2012).

Ara, A. & Usmani, J. A. Lead toxicity: a review. Interdisciplinary Toxicol. 8, 55–64 (2015).

Yüksel, B., Kayaalti, Z., Kaya-Akyüzlü, D., Tekin, D. & Söylemezoglu, T. Assessment of lead levels in maternal blood samples by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry and influence of maternal blood lead on newborns. Spectrosc. 37, 114–119 (2016).

Schnaas, L. et al. Reduced intellectual development in children with prenatal lead exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 114, 791–797 (2006).

Liu, J., Li, L., Wang, Y., Yan, C. & Liu, X. Impact of low blood lead concentrations on IQ and school performance in Chinese children. PloS One 8, e65230 (2013).

Mohammadi, S., Shafiee, M., Faraji, S. N., Rezaeian, M. & Ghaffarian-Bahraman, A. Contamination of breast milk with lead, Mercury, arsenic, and cadmium in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biometals 35, 711–728 (2022).

Proshad, R., Zhang, D., Uddin, M. & Wu, Y. Presence of cadmium and lead in tobacco and soil with ecological and human health risks in Sichuan Province, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 18355–18370 (2020).

Brima, E. I. Determination of metal levels in Shamma (smokeless tobacco) with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) in Najran, Saudi Arabia. Asian Pac. J. cancer Prevention: APJCP. 17, 4761 (2016).

Dhaware, D., Deshpande, A., Khandekar, R. & Chowgule, R. Determination of toxic metals in Indian smokeless tobacco products. Sci. World J. 9, 1140–1147 (2009).

McNeill, A., Bedi, R., Islam, S., Alkhatib, M. & West, R. Levels of toxins in oral tobacco products in the UK. Tob. Control 15, 64–67 (2006).

Borgerding, M. F., Bodnar, J. A., Curtin, G. M. & Swauger, J. E. The chemical composition of smokeless tobacco: A survey of products sold in the united States in 2006 and 2007. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 64, 367–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2012.09.003 (2012).

Song, M. A. et al. Chemical and toxicological characteristics of conventional and low-TSNA moist snuff tobacco products. Toxicol. Lett. 245, 68–77 (2016).

Al-Mukhaini, N., Ba-Omar, T., Eltayeb, E. & Al-Shehi, A. Determination of heavy metals in the common smokeless tobacco Afzal in Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 14, e349 (2014).

Chen, X. X., Xu, Y. M. & Lau, A. T. Metabolic effects of long-term cadmium exposure: an overview. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 89874–89888 (2022).

Ghaffarian-Bahraman, A., Shahroozian, I., Jafari, A. & Ghazi-Khansari, M. Protective effect of magnesium and selenium on cadmium toxicity in the isolated perfused rat liver system. Acta Med. Iranica 872–878 (2014).

Genchi, G., Sinicropi, M. S., Lauria, G., Carocci, A. & Catalano, A. The effects of cadmium toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 3782 (2020).

Taha, M. M., Mahdy-Abdallah, H., Shahy, E. M., Ibrahim, K. S. & Elserougy, S. Impact of occupational cadmium exposure on bone in sewage workers. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 24, 101–108 (2018).

Rahaman, M. S. et al. Environmental arsenic exposure and its contribution to human diseases, toxicity mechanism and management. Environ. Pollut. 289, 117940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117940 (2021).

Yüksel, B., Sen, N., Tutkun, T. Ü. R. K. S. O. Y. V. & Söylemezoğlu, T. E. Effect of exposure time and smoking habit on arsenic levels in biological samples of metal workers in comparison with controls. Marmara Pharm. J. 22 (2018).

Lugon-Moulin, N., Martin, F., Krauss, M. R., Ramey, P. B. & Rossi, L. Arsenic concentration in tobacco leaves: a study on three commercially important tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) types. Water Air Soil Pollut. 192, 315–319 (2008).

Genchi, G., Carocci, A., Lauria, G., Sinicropi, M. S. & Catalano, A. Nickel: Human health and environmental toxicology. International journal of environmental research and public health. 17, 679 (2020).

Sinicropi, M. S., Amantea, D., Caruso, A. & Saturnino, C. Chemical and biological properties of toxic metals and use of chelating agents for the Pharmacological treatment of metal poisoning. Arch. Toxicol. 84, 501–520 (2010).

Yüksel, B., Arıca, E. & Söylemezoğlu, T. Assessing reference levels of nickel and chromium in cord blood, maternal blood and placenta specimens from Ankara, Turkey. J. Turkish German Gynecol. Association. 22, 187 (2021).

Khan, Z., Suliankatchi, R. A., Heise, T. L. & Dreger, S. Naswar (smokeless tobacco) use and the risk of oral cancer in Pakistan: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 21, 32–40 (2019).

Mohammadi, S., Kosari, A., Eslami, H., Moghadam, E. F. & Ghaffarian-Bahraman, A. Toxic metal contamination in edible salts and its attributed human health risks: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 1–12 (2025).

Wang, Z. et al. Identification of novel uncertainty factors and thresholds of toxicological concern for health hazard and risk assessment: application to cleaning product ingredients. Environ. Int. 113, 357–376 (2018).

Dankovic, D., Naumann, B., Maier, A., Dourson, M. & Levy, L. The scientific basis of uncertainty factors used in setting occupational exposure limits. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 12, S55–S68 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study is the outcome of a research project (code 400180) approved by the occupational environment research center of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences (RUMS), with the ethics code IR.RUMS.REC.1400.190. This work was supported by the RUMS. The funder has played no role in the design of the study or in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data. We extend our gratitude to RUMS for its support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MR and AGB conceived and designed the experiment. AGB and MSR collected the data. HA performed statistical analysis. AD and AE cooperated in interpretation of the results. AGB, HM and AD participated in finalizing the draft script with their literary and scientific editions. All authors were actively cooperated in writing the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

By submitting this document, the authors declare their consent for the final accepted version of the manuscript to be considered for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rezaeian, M., Ahmadinia, H., Rabori, M.S. et al. Human health risk assessment of toxic metals in Nass smokeless tobacco in Iran. Sci Rep 15, 9525 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93755-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93755-2