Abstract

This study aims to verify the safety and effectiveness of complex surgical procedures like hepato-pancreatic and biliary (HPB) surgery also in General Surgery Units when performing an Hub&Spoke Learning Program (H&S) with a referral center. This approach leads reduction of health migration and related costs for patients and health system granting the same standard of medical and surgical care in Spoke Units. Implementation of H&S through a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected database comparing, after a Propensity Score Matching (PSM) analysis, baseline characteristics and peri-operative outcomes of patients undergone HPB surgery in a referral center (Hub) and in three peripheral centers (Spokes) under the mentoring program. Hub Hospital was represented by the Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery Center in Pineta Grande Hospital (Castel Volturno, Caserta, Italy), while the Spoke Units were the General Surgery Unit of Padre Pio Hospital (Mondragone, Caserta, Italy), the General Surgery Unit of C.T.O. Hospital (Naples, Italy) and the General and Emergency Surgery Unit of A. Cardarelli Hospital, University of Molise (Campobasso, Italy). During the partnership program, from January 2016 to June 2023, H&S enrolled 298 and 156 consecutive patients respectively. After PSM, data of 150 patients for each group were analyzed. After PSM no differences were found concerning patients baseline characteristics. Hub group selected more often primary liver cancers versus benign lesions and liver metastasis more frequent in the Spoke group. All peri-operative data were superimposable except for blood transfusion, Pringle maneuver and length of hospital stay that were more frequent in the Hub group. We can conclude that the treatment of liver cancers in peripheral centers is possible, safe and effective especially under a H&S. There are some requisites to be successful like experienced surgeon(s), interdisciplinary meetings to discuss and minimum requirements in each hospital such as Intensive Care Unit, interventional radiology and emergency facilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Widespread Healthcare is worldwide suffering1. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has drastically reduced resources devoted to wide-range programs for basic and complex healthcare procedures2,3. As a consequence, the life expectancy in Italy has decreased by 1.2 year4 and complex cases come to surgical evaluation in worse clinical conditions5,6.

Particularly, Italy has been suffering since longtime of health migration from south to the northbound because of the different number of referral centers/regions covering all health needs in specialized fields such as transplants, cardiac surgery, hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery7,8 and many more non-surgical specialties9.

The COVID-19 pandemic has inevitably reduced health mobility because of health restrictions and economic shortages, therefore challenging southern specialty Centers to take care of more complex cases10,11,12.

Some papers have already been published concerning the efficacy of Hub&Spoke training programs (H&S) either in hepato-pancreatic and biliary (HPB) Surgery either in other surgical specialties13,14.

Following previous experiences in HPB12,15 our institution Pineta Grande Hospital (PGH, Castel Volturno, Caserta) has progressively started in the years a transregional cooperation program in Hepato-Biliary Surgery (HBS) with the Padre Pio Hospital (Mondragone, Caserta), the C.T.O. Hospital (Naples) and the University Hospital A. Cardarelli (Campobasso).

The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate the safety and reliability of H&S in hepatobiliary surgery (HB) in three different Units dedicated to general surgery in Southern Italy. We will analyze as primary endpoint the safety and efficacy of the training program evaluating the peri-operative mortality defined as Clavien-Dindo (CD) V classification of complications after surgery, and the number, the type and CD score occurred in the Hub Center (1 Unit) and in the Spoke centers (3 Units).

Despite we well know that very complex clinical pictures will be always treated in referral centers, for low-and medium-complex surgeries, our underlying aim is to encourage the implementation of these programs, allowing the improvement surgical and non-surgical skills of peripheral centers in the management of HPB patients, in the hope of reducing the need for health migration and following nuisance and costs for our patients granting the same standard of medical and surgical care.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively reviewed a prospectively collected database of patients undergoing HB surgery at the Hub Hospital represented by the Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery Center in Pineta Grande Hospital (Castel Volturno, Caserta, Italy), while the Spoke Units were the General Surgery Unit of Padre Pio Hospital (Mondragone, Caserta, Italy), the General Surgery Unit of C.T.O. Hospital (Naples, Italy) and the General and Emergency Surgery Unit of A. Cardarelli Hospital, University of Molise (Campobasso, Italy) from January 2016 to June 2023. Appendix 1 resume surgeons’ skills and hospitals’ facilities. Patients were divided in two cohorts: Hub group and Spoke Units group (Fig. 1, A-B).

From January 2016 to June 2023 the Hub Unit performed more than 40 liver resections per year. During the partnership program Hub and Spoke Units enrolled 298 and 156 consecutive patients respectively (Fig. 1). After 1:1 PSM, data of 150 patients for each group were analyzed (Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4). An informed consent to the anonymous scientific use of clinical data was obtained by each patient. This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Molise (protocol number 10/21, approved date: May 12, 2021).

Inclusion criteria were:

-

Age ≥ 18 y.o.;

-

Acquired informed consensus;

-

Patients undergone liver surgery.

Exclusion criteria were represented by:

-

Age < 18 y.o.

-

Lack of patient compliance,

-

Patients affected by perihilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Preoperative workup

The preoperative study of patients was carried out according to the gold standard clinical assessment and imaging technique for each HB case16,17,18. A multidisciplinary team (surgeons, radiologists, interventional radiologists, endoscopists, anesthesiologists and oncologists) discussed each case identifying the best patient management. When the clinical and radiological characteristics of the Spoke Units cases pointed out a high risk of potential complications or a poor prognosis prediction (high anesthesiological risk, ≥ 5 number of lesions, challenging position of lesions, high risk of liver failure) the patient was transferred to the Hub Unit, allowing the Spoke surgeons to perform the surgical procedure in a high volume center19. Patients were informed of the surgical collaboration to improve the quality of health care assistance.

Hub and spoke training program

Our H&S model was based on HPB surgical mentor (Castel Volturno team) supervised the pre-, intra-, and post-operative care of patients to train spoke centers. Multidisciplinary online conferences were conducted to review patient data (Fig. 2). These discussions included thorough assessments of patients’ surgical fitness and comprehensive reviews of radiological imaging. The weekly MDT discussions have not only the aim to assess patient treatment strategy but also being education session for spoke teams. The postoperative management involved sharing clinical data, blood test results, and radiological findings daily to address complications effectively. The H&S model engaged both physicians and nurses from both centers. Notably, after completing the H&S training program, the teams significantly improved their surgical skills, reducing their reliance on a mentor for less complex procedures. During the learning curve, the mentor actively performed one-on-one liver resections. In the latter part of the program, the mentor’s role shifted to providing guidance within the operating room. The mentor mandates participation in at least two specialized courses or congresses organized by prominent national and international scientific societies, aiming to advance the theoretical knowledge and practical expertise of all personnel undergoing training.

Postoperative follow-up

After surgery, the postoperative management of patients was performed thanks to a continuously sharing of clinical data, imaging, and blood tests day-by-day to treat any eventual complications. After discharge, the patient underwent oncological follow-up according to Italian Guidelines16,17,18.

Primary and secondary endpoints

The perioperative outcomes of the patients were evaluated to assess the safety and effectiveness of the H&S Training Program. Baseline characteristics of patients were set up including: histological diagnosis, surgical approach (open, laparoscopy), definition of minor or major resection according to Brisbane classification20, operative time (min), blood loss (ml), transfusion rate (%), use and duration (min) of the Pringle maneuver, ICU stay (days), hospital stay (days), mortality rate (%). Major hepatectomy was defined as the resection of ≥ 3 Couinaud segments20. Postoperative complications were stratified according to Clavien-Dindo classification (CD)21. Liver-specific complications were recorded: ascites, abdominal drainage output > 10 ml per kg bodyweight per day on POD 3, biliary leakage as a bilirubin concentration x3 times compared to serum level in abdominal drainage fluid, eventual liver failure on POD 522.

Propensity-score matching and power analysis

A Propensity Score Matching (PSM) was performed to overcome the bias due to patients’ selection and characteristics. We obtained the PSM using a logistic regression model that included: age23,24, sex24,25, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification24,26, major and minor surgical resections. After estimation of PSM, a regular 1:1 Nearest-Neighbour matching was performed27. The PSM was carried out using XLSTAT statistical and data analysis solution (Lumivero 2023, Paris, France). The power analysis was carried out to evaluate the non-inferiority of surgical procedures performed by Spoke Unites when compared to Hub. With a significance criterion of α = 0.05 and power = 0.80, the minimum sample size required is N = 11828. Thus, the obtained sample size of N = 300 (150 patients in Hub and 150 patients in Spoke Units) is deemed to be adequate to test the study hypothesis29.

Statistical analysis

Each team collected a default Microsoft Excel Database. First step consisted of a lengthily analysis to assess the data quality. Then data were collected into a single Microsoft Excel Database. Quantitative variables were described as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR). T-test was performed to analyze normal distributed variables, while Chi-square test (χ2) or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare qualitative variables. A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was recognized as statistically significant. Data analysis was pointed out with IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS®).

Results

In Table 1 we collected baseline characteristics of patients before and after PSM.

No differences were found according to age, sex and BMI between Hub and Spoke unites. Although, before PSM there were statistical differences between Hub and Spoke Unites according to ASA II and III (p = 0.0001), after PSM the two groups were homogeneous.

Before matching, patients in the Hub hospital had a higher prevalence of cardiac disease (15.44% vs. 8.33%, p = 0.0391) and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) (14.76% vs. 1.28%, p = 0.0001) compared to those in the Spoke units.

The main surgical indication in the Hub Unit were Colorectal Liver Metastasis (CLRM, 35.33%), Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA, 23.33%) followed by Hepatocarcinoma (HCC, 18.67%), while CRLM (35.33%) and HCC (22.67%) were the most representative diseases in the Spoke Units (Table 1).

Iatrogenic injuries were not excluded from the analysis either to demonstrate the efficacy of the referral program to the Hub centers for complex cases, either because the less complex procedures were performed by training surgeons under the supervision of tutors with benefits of the Hub centres facilities (included anesthesiologic and radiological skills). Future perspectives of our collaboration will be taken into account the chance to manage less complex biliary injuries also in Spoke Units.

There was a significantly lower rate of liver resections for benign lesions in the Hub Unit. We reported cyst fenestration as observational data to demonstrate that the laparoscopic approach to liver cysts might be used as a training step for surgeons in Spoke Units. The importance of cyst management is underlined by its management also in the Hub centers. Furthermore, in Hub&Spoke learning program to speed up the waiting list Hub centers might safely address cyst management in Spokes Units. About gallbladder cancers, according to national and international guidelines, we performed gallbladder bed resections and lymph node excision. It might be considered as a minor liver resection associated to regional lymphadenectomy which is also common in other surgical procedures. So, gallbladder cancers may be indicated as learning stepwise procedures under tutoring in Spoke Units. Those considerations are added in the discussion paragraph.

Nevertheless, after PSM no statistical differences were observed between major or minor surgical procedures and open or laparoscopic approaches (Table 2). Intraoperative outcomes are listed in Table 2.

Before matching, the Hub hospital performed significantly more open surgical approaches (76.17% vs. 64.74%, p = 0.0112) and major liver resections (54.03% vs. 41.66%, p = 0.0136) compared to Spoke units. Additionally, patients in the Hub hospital underwent the Pringle maneuver more frequently (69.13% vs. 44.87%, p = 0.0001). After matching, the differences in the type of surgical approach, major liver resections, and operative time between the Hub and Spoke hospitals were not statistically significant. However, the use of the Pringle maneuver remained significantly higher in the Hub hospital (60.67% vs. 46.67%, p = 0.0204). Intraoperative blood transfusion rates were also higher in the Hub hospital (14.67% vs. 6%, p = 0.0216) (Table 2).

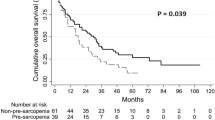

The postoperative ICU stay was higher in Spoke Unites (1.8 vs. 3.4 days, p = 0.0001), while CD ≥ III showed similar rates between the two groups (p = 0.1870) (Table 3). Mortality was 2% in whole series, with 4 patients died into the HUB group and 2 patients died in the Spoke one.

Length of hospital stay was shorter in the Spoke Unites (9.08 vs. 11.57 days, p = 0.0291).

Table 4 included surgical procedures performed in Hub and Spoke Unites during collaboration period.

Baseline characteristics and intra- and post-operative outcomes of patients transferred to Hub Unit were listed in Table 5.

Discussion

This paper is the result of a challenge: putting into reality the H&S principles of teaching and disseminating complex surgery, like hepatobiliary in the case. The analysis of data demonstrates that performing liver resections also in peripheral centers might be safe and effective. Requisites to be successful are: experienced surgeon(s), interdisciplinary meetings to discuss each case and minimum requirements in each hospital such as Intensive Care Unit, interventional radiology and emergency facilities30.

More in detail we want underline that the National Agency for Regional Health Services (AGENAS) has revealed that the Campania Region has lost the 33% of patients affected by HB diseases going to Center-North centres in the country to take care of liver cancers from 2017 to 20229.

To limit health migration, regional health institutions have therefore allowed formal relationships between referral centers and peripheral units to improve patient care in the nearby of their residence, for this reason it is important to test the safeness and effectiveness of the H&S program.

First, it should be considered that baseline characteristics between the two groups of patients are very well balanced after PSM analysis, allowing a reliable analysis of data, considering that patients allocation was not random but consequent to MDT discussions and indications.

Concerning surgical indications, we can affirm that benign pathologies and CRLM resections are performed more common in peripheral centers, on the other hand challenging clinical picture, like HCC, Biliary cancers and biliary injuries are preferably transferred to the referral center. It is clear that the multidisciplinary discussion with both equips decided if it was reliable to treat the patient in the Hub or in the Spoke units, probably also for this reason the most complex procedures were related to Hub.

Before PSM, baseline characteristics of patients who underwent HB surgery at Hub and Spoke Units were aligned with other literature experiences12,31,32. The higher ASA score in Hub Unit (p = 0.0001) and the significative higher number of comorbidities should be noted. Therefore, the use of PSM allowed to homogenize populations to reduce the bias during intra- and post-operative outcomes analysis (Table 1), considering the age and comorbidities impact on postoperative complications23,33.

Intra-operative data revealed superimposable outcomes regarding operative time and type of surgical approaches. After PSM, similar distributions of major and minor liver resection were reported. Despite these findings higher Pringle Maneuver and blood transfusion rates were performed in the Hub Unit, it is probably due to the type of indications and the greater number of cirrhotic patients who needed stricter management of bleeding due to coagulation disorder34. Despite these findings, our data are in line with other literature experiences22,35,36.

Major morbidity and mortality rates range around 15% and 2% respectively, in trend with the standard of care for liver surgery as demonstrated in several reports from high experienced centers37,38,39. Furthermore, the majority of complications are Clavien-Dindo I-II representing more than the 80% of cases40,41.

As main goal of our project we can assess that post-operative complications are similar between centers, except for ICU stay, but it should be clarified that in the HUB center ICU is only a post-operative intensive care where patients stay for 24 h, on the other hand this way of post-operative Intensive Care Unit is not available in spokes where there is only the resuscitation care unit.

From the data analysis, we can infer that several patients affected by benign pathologies or who needed iterative treatments for colorectal cancer or affected by non-complex liver cancers had the chance to be cured in the nearby of their home without any discomfort.

This is one of the benefits of the H&S program which allowed peripheral centers to benefit of the multidisciplinary making process, granting to patients the best therapeutic option, involving all the physicians from oncology to radiology also expanding the learning process in the whole field of cancer therapy.

On the other hand, surgeons from the Hub hospital, who were highly trained, are happy to share their knowledge with the Spokes Unites teams having the opportunity to cure some liver patients in the peripheral centers shortening their waiting lists. At the same time, the training program gave to spoke surgeons the chance to operate more complex patients, improving their skills and treatments offered to their patients.

It is crucial to understand that the H&S learning program is an iterative process that aims to give the chance to peripheral centers to set dedicated HB Units who can manage even more patients achieving autonomy and they can have the help of the training center where patients can be referred in case of need.

One of the weak point of the H&S training program it is always represented by the management of post-operative complications13, but the low distance between centers and the presence in both equips of mentor and training surgeons reduced this criticism, allowing also the mobility of patients from peripheral centers to the Hub in case of need. Furthermore, as depicted in results, there are not statistical evidences of a worse management or higher incidence of complication in the Spoke group.

Patient feelings were also supportive, they were aware of the H&S learning program being more confident about their pathway care without the inconvenience of health mobility. Furthermore the presence of the surgical hospital in the surrounding of their residence improved the early discharge13. This may explain why the LOS in the Hub was longer than in spokes, probably because complex and frail patients are more difficult to discharge when patients are far from the surgical center.

Especially concerning CRLM it is very important to perform liver surgery in the same hospital where patients underwent primary resection and chemotherapy, taking advantage of continuity of care.

Noticeably, the objective of our learning program is not to convert peripheral centers into referral centers for HPB, Hub centers remain the referral for complex cases and specific indications.

Our goal is to reduce costs of health mobility and improve the surgical knowledge physicians always offering the best care management of liver pathologies.

The age of images has undoubtedly shortened the learning curve, particularly in HPB surgery. To look and look via videos at the surgical field closer as never before, has raised more quickly surgeons able to face open difficult surgery and particularly HPB one42,43,44,45.

Conversely, Viganò et al.30 reported, through a CUSUM analysis, that a learning curve of 60 cases is necessary for laparoscopic hepatectomies. Others have reported that the learning curve for Minimally Invasive Hepatectomies (MIH) ranges widely, from 20 to over 80 cases30,46,47.

In case of open hepato-biliary surgery the learning curve significantly decreases but it is always related to the type of hepatectomy, major or minor ones48,49.

Limitations

Our analysis showed some limitations, first of all it is a retrospective analysis, furthermore Spoke Units shows different characteristics in terms of surgical and hospital facilities. Despite of PSM analysis based on pre- and intra-operative data of patients, unknown confounders might have a significant impact on post-operative outcomes.

Conclusion

We can conclude that the treatment of liver disease in peripheral centers is possible, safe and effective especially under an H&S learning training program. There are some requisites to be successful like experienced surgeon(s), interdisciplinary meetings to discuss and address each case to the best treatment option and minimum requirements in each hospital such as Intensive Care Unit, interventional radiology and emergency facilities.

Obviously further prospective studies from different countries may be useful to set the best protocol to perform H&S learning program especially dedicated to liver surgery.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sleeman, K. E. et al. The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. Lancet Glob. Health 7(7), e883–e92 (2019).

Aldrighetti, L. et al. Perspectives from Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic: nationwide survey-based focus on minimally invasive HPB surgery. Updates Surg. 72(2), 241–247 (2020).

Bracale, U. et al. Changes in surgical behaviors dUring the CoviD-19 pandemic. The SICE CLOUD19 study. Updates Surg. 73(2), 731–744 (2021).

Mara Gaurino, M. T. L’Italia che invecchia anche dopo COVID-19 Itinerari previdenziali2022. https://www.itinerariprevidenziali.it/site/home/ilpunto/economia-societa/italia-che-invecchia-anche-dopo-covid-19.html (2022).

Mohseni Afshar, Z. et al. Challenges posed by COVID-19 in cancer patients: a narrative review. Cancer Med. 11(4), 1119–1135 (2022).

Riera, R. et al. Delays and disruptions in cancer health care due to COVID-19 pandemic: systematic review. JCO Glob. Oncol. 7, 311–323 (2021).

Balzano, G. et al. Geographical disparities and patients’ mobility: a plea for regionalization of pancreatic surgery in Italy. Cancers (Basel) ;15, 9 (2023).

Ricciardi, W. & Tarricone, R. The evolution of the Italian National health service. Lancet 398(10317), 2193–2206 (2021).

AGENAS PS. Focus della mobilità per patologie oncologiche: AGENAS. https://stat.agenas.it/web/index.php?r=public%2Findex&report=15 (2022).

Buondonno Antonio, A. P. et al. A hub and spoke learning program in bariatric surgery in a small region of Italy. Front. Surg. (2022).

Rocca, A. et al. Oncologic colorectal surgery in a general surgery unit of a small region of Italy—a successful referral centre hub & spoke learning program very important to reduce mobility in the Covid-19 era (2022).

Ceccarelli, G. et al. Robot-assisted liver surgery in a general surgery unit with a referral centre hub&spoke learning program. Early outcomes after our first 70 consecutive patients. Minerva Chir. 73(5), 460–468 (2018).

Ravaioli, M. et al. A partnership model between high- and low-volume hospitals to improve results in hepatobiliary pancreatic surgery. Ann. Surg. 260(5), 871–875 (2014).

Elrod, J. K. & Fortenberry, J. L. Jr. The hub-and-spoke organization design: an avenue for serving patients well. BMC Health Serv. Res. 17(Suppl 1), 457 (2017).

Rocca, A. et al. Robotic versus open resection for colorectal liver metastases in a referral centre hub&spoke learning program. A multicenter propensity score matching analysis of perioperative outcomes. Heliyon 10(3), e24800 (2024).

AIOM AIdOM. Linee guida Tumori delle Vie Biliari2019 (2019).

(AIOM) AIdOM. Linee Guida Epatocarcinoma2020 (2020).

(AIOM) AIdOM. Linee guida tumore del colon2021 (2024).

Torzilli, G., Viganò, L., Giuliante, F. & Pinna, A. D. Liver surgery in Italy. Criteria to identify the hospital units and the tertiary referral centers entitled to perform it. Updates Surg. 68(2), 135–142 (2016).

Strasberg, S. M. Nomenclature of hepatic anatomy and resections: a review of the Brisbane 2000 system. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Surg. 12(5), 351–355 (2005).

Dindo, D., Demartines, N. & Clavien, P. A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 240(2), 205–213 (2004).

Cipriani, F. et al. Propensity score-based analysis of outcomes of laparoscopic versus open liver resection for colorectal metastases. Br. J. Surg. 103(11), 1504–1512 (2016).

Ruzzenente, A. et al. Impact of age on short-term outcomes of liver surgery: lessons learned in 10-years’ experience in a tertiary referral hepato-pancreato-biliary center. Med. (Baltim). 96(20), e6955 (2017).

Tohme, S., Varley, P. R., Landsittel, D. P., Chidi, A. P. & Tsung, A. Preoperative anemia and postoperative outcomes after hepatectomy. HPB (Oxford). 18(3), 255–261 (2016).

Birrer, D. L. et al. Sex disparities in outcomes following major liver surgery: new powers of Estrogen? Ann. Surg. 276(5), 875–881 (2022).

Owens, W. D., Felts, J. A. & Spitznagel, E. L. Jr. ASA physical status classifications: a study of consistency of ratings. Anesthesiology 49(4), 239–243 (1978).

Geldof, T., Popovic, D., Van Damme, N., Huys, I. & Van Dyck, W. Nearest neighbour propensity score matching and bootstrapping for estimating binary patient response in oncology: a Monte Carlo simulation. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 964 (2020).

Blackwelder, W. C. Proving the null hypothesis in clinical trials. Control Clin. Trials. 3(4), 345–353 (1982).

Ltd, S. E. Power calculator for binary outcome non-inferiority trial. https://www.sealedenvelope.com/power/binary-noninferior/ (2012).

Vigano, L. et al. The learning curve in laparoscopic liver resection: improved feasibility and reproducibility. Ann. Surg. 250(5), 772–782 (2009).

Di Benedetto, F. et al. Safety and efficacy of robotic vs open liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. JAMA Surg. 158(1), 46–54 (2023).

Morris-Stiff, G. et al. Redefining major hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases: analysis of 1111 liver resections. Int. J. Surg. 25, 172–177 (2016).

Russolillo, N. et al. The influence of aging on hepatic regeneration and early outcome after portal vein occlusion: A Case-Control study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 22(12), 4046–4051 (2015).

O’Leary, J. G., Greenberg, C. S., Patton, H. M. & Caldwell, S. H. AGA clinical practice update: coagulation in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 157(1), 34–43e1 (2019).

Sugiyama, Y. et al. Effects of intermittent Pringle’s manoeuvre on cirrhotic compared with normal liver. Br. J. Surg. 97(7), 1062–1069 (2010).

Al-Saeedi, M. et al. Pringle maneuver in extended liver resection: a propensity score analysis. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 8847 (2020).

Berardi, G. et al. Model to predict major complications following liver resection for HCC in patients with metabolic syndrome. Hepatology 77(5), 1527–1539 (2023).

Scuderi, V. et al. Outcome after laparoscopic and open resections of posterosuperior segments of the liver. Br. J. Surg. 104(6), 751–759 (2017).

de Geus, S. W. et al. Combined hepatopancreaticobiliary volume and hepatectomy outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma patients at Low-Volume liver centers. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 232(6), 864–871 (2021).

Magnin, J. et al. Impact of hospital volume in liver surgery on postoperative mortality and morbidity: nationwide study. Br. J. Surg. 110(4), 441–448 (2023).

Guglielmi, A. et al. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality in hepato-biliary surgery in Veneto region, Italy. Updates Surg. 75(7), 1949–1959 (2023).

Green, J. L. et al. The utilization of video technology in surgical education: a systematic review. J. Surg. Res. 235, 171–180 (2019).

Ahmet, A., Gamze, K., Rustem, M. & Sezen, K. A. Is Video-Based education an effective method in surgical education? A systematic review. J. Surg. Educ. 75(5), 1150–1158 (2018).

Augestad, K. M., Butt, K., Ignjatovic, D., Keller, D. S. & Kiran, R. Video-based coaching in surgical education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg. Endosc. 34(2), 521–535 (2020).

Hogg, M. E. et al. Training in minimally invasive pancreatic resections: a paradigm shift away from see one, do one, teach one. HPB (Oxf.) 19(3), 234–245 (2017).

Cho, J. Y., Han, H. S., Yoon, Y. S. & Shin, S. H. Experiences of laparoscopic liver resection including lesions in the posterosuperior segments of the liver. Surg. Endosc. 22(11), 2344–2349 (2008).

Brown, K. M. & Geller, D. A. What is the learning curve for laparoscopic major hepatectomy?? J. Gastrointest. Surg. 20(5), 1065–1071 (2016).

Banas, B., Gwizdak, P., Zabielska, P., Kolodziejczyk, P. & Richter, P. Learning curve for metastatic liver tumor open resection in patients with primary colorectal cancer: use of the cumulative sum method. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19, 3 (2022).

Banas, B. et al. Single-Centre study on the learning curve for liver tumor open resection in patients with hepatocellular cancers and intrahepatic cholagangiocarcinomas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19, 8 (2022).

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work has been partially supported by National Plan for NRRP Complementary Investments D3 4 Health: Digital Driven Diagnostics, prognostics and therapeutics for sustainable Health care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R. and F.C.; methodology, A.R. and P.A. (Pasquale Avella); validation, A.R., P.A. (Pasquale Avella), M.C.B., G.G., L.B.; formal analysis, P.A. (Pasquale Avella); clinical investigation, all authors; investigation, all authors; data curation, P.A. (Pasquale Avella); writing—original draft preparation, A.R., P.A. (Pasquale Avella), F.C., writing—review and editing, A.R., P.A. (Pasquale Avella), P.B., P.A. (Pierluigi Angelini), F.C.; supervision: G.G., L.B., F.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Collaborative Group: all physicians were clinically involved in the Hub&Spoke program.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Molise (protocol number 10/21, approved date: 12 May 2021).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rocca, A., Avella, P., Bianco, P. et al. Propensity score matching analysis of perioperative outcomes during Hub&Spoke training program in hepato-biliary surgery. Sci Rep 15, 10743 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93781-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93781-0