Abstract

Due to extended thermal carrier lifespan, small bandgap, and biocompatibility, tin (Sn)-based perovskite solar cells (PSCs) have garnered attention. Sn-based PSCs (nip-type), however, have performed poorly, mostly because of the careless application of metal oxide electron transport layers (ETLs), which were first created for lead-based PSCs of the nip type. The metal oxides deeper energy levels and oxygen vacancies are too responsible for this underperformance. In order to overcome these problems, we demonstrate a metal chalcogenide ETL, namely Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2, which prevents the oxidation of Sn2+ and avoids the desorption of oxygen molecules. The variation of several charge transport layers is thoroughly analyzed in this work, indicating that SnS2, TiO2, and metal-doped Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 are viable options to improve the efficiency of the FASnI3 (Energy gap (Eg) ≈ 1.41electron volt (eV) PSC. With Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 as ETL and PTAA as Hole transport layer (HTL), the PSC’s performance is maximized and the optimal performance device structure is attained. For our investigation, the optimal device structure is (Au/PTAA/FASnI3/Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2/FTO). We obtain an outstanding optimized value of Power conversion efficiency (PCE) 32.22%, Open circuit voltage (VOC) 1.2762 V, Fill factor (FF) 81.87%, and Short-circuit current density (JSC) 30.836 mA.cm− 2 by carefully evaluating and optimizing a number of variables, such as thickness of active layer, ETL and HTL, Acceptor density (NA), Defect density (Nt) vs. thickness variation, Interface defect (IDD) and temperature variation. These findings provide a viable pathway for enhancing the efficiency of Sn-based PSCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

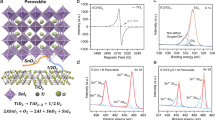

PSCs have become a game-changing technology in the domain of green energy because of their remarkable PCEs, affordable production methods, and adjustable optoelectronic characteristics1,2,3,4. Perovskite materials using the ABX3 formula, in which A stands for the larger cation of either organic (CH3NH3+, MA or HC(NH2)2+, FA) or inorganic (alkali metal Cs+) nature, B for the smaller divalent metal cation (Pb2+ or Sn2+), and X for a single halide anion or mixture (Cl−, Br− or I−)5,6,7,8. By carefully selecting these cations and anions, device stability and efficiency may be increased. Among these, lead (Pb)-based PSCs, like FAPbI3 and methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3), have dominated the field due to their remarkable optoelectronic characteristics, which include excellent charge carrier mobilities, tunable bandgaps, and high absorption coefficients. However, Pb intrinsic toxicity presents a major risk to both human health and the environment, making the widespread commercialization of Pb-based PSCs extremely difficult9,10,11. Because of these difficulties, scientists are now concentrating on creating eco-friendly substitutes. Tin (Sn)-based perovskites (TPSCs) have become a popular option because of their potential optoelectronic qualities and lack of toxicity. Notably, the Shockley-Queisser limit indicates that TPSCs have a greater theoretical PCE than Pb-based PSCs12,13. They are also perfect for use in multi-junctions, which are essential for reaching efficiencies higher than the single-junction limit because to their small bandgap. TPSC are now the most promising Pb-free perovskite substitute, having shown PCEs above 15%14,15,16. Despite these benefits, TPSCs still have a number of drawbacks, especially when it comes to the extensively researched nip-type design, which has proven to have better thermal stability and more affordable materials than the pin-type structure. Although record-breaking PCEs in Pb-based PSCs have previously been achieved in nip-type PSCs, their performance in TPSCs has been hampered by negligent utilization of functional materials from Pb-based systems. In particular, tin-based perovskites do not work well with frequently used metal oxide ETLs like TiO2 and SnO2. This results in low open-circuit voltages (VOC less than 0.5 V) and inadequate efficiencies. Mismatched band alignments and oxygen vacancies in metal oxides, which worsen recombination losses, are responsible for these restrictions17. The unique metal chalcogenide ETL Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 is investigated in this work as a potential option for nip-type TPSCs, which provide better band alignment, increased electron mobility, and lower defect concentrations, in order to overcome these problems18. The Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 ETL, in contrast to traditional metal oxide ETLs, not only avoids O2 molecule removal but also prevents the interaction between Sn2+ ions in TPSC and atmospheric O2 molecules19,20,21,22. In addition, the conduction band minimum position of the Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 ETL is shallower than that of its metal oxide equivalents23,24,25,26. An aligned energy level, optical transparency, and a compact geometry free of pinholes, high conductivity, and high carrier mobility are some of the essential characteristics of the most suitable ETL for nip-type Tin PSCs. Previous research that looked at Sn-based perovskite was able to produce a variety of PCEs by optimizing a number of features of the solar cell structure. A PCE of 14.03% was attained by Abdelaziz et al. using a variety of HTL and ETL candidates, including CuI, Cu2O, NiO, ZnO, and ZnSe27. The simulated SnO2/FASnI3/PCBM PSCs were reported by Ritu et al., who discovered a 24.54% PCE, VOC 0.97 V, JSC 29.88 mA.cm− 2.28 Almufarij et al. found that adding double layers of MoO3/Si HTLs increased PCE by 30.45%. The recombination losses in FASnI3 are enhanced by the second layer29. The maximum efficiency of 21.63% is reported by Talebi et al. using Cu2ZnSnSe4 HTL. The variation of several charge transport layers is thoroughly analyzed in this work, indicating that SnS2, TiO2, and metal-doped Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 are viable options to improve the efficiency of the FASnI3 (Eg ≈ 1.41 eV) PSC. A layered material with a high electron affinity, SnS2 reduces charge recombination and promotes effective electron transport. As a tin-based chalcogenide, SnS2 and FASnI3 are intrinsically compatible, which minimizes the possibility of Sn2+ oxidation problems at the interface. Its chemical stability is also better than that of TiO2 in lead-free perovskite devices30,31. High electron mobility, efficient charge extraction, and well-matched conduction band offset with FASnI3 make TiO2 a popular material. The selection of PTAA as HTL is based on its high hole mobility, hydrophobicity, and capacity to decrease interfacial defects, which results in enhanced FF and VOC32,33,34,35,36. With Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 as ETL and PTAA as HTL, the PSC’s performance is maximized and the optimal performance device structure is attained. For our investigation, the optimal device structure is (Au/PTAA/FASnI3/Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2/FTO). We obtain an outstanding optimized value of PCE 32.22%, VOC 1.2762 V, FF 81.87%, and JSC 30.836 mA.cm− 2 by carefully evaluating and optimizing a number of variables, such as thickness of active layer, ETL and HTL, NA, Nt vs. thickness variation, IDD & temperature variation, and current- voltage (J-V) and external quantum efficiency (EQE) variation.

Material simulation method & FASnI 3 based device structure

This study’s main objective is to use SCAPS-1D tool to simulate and analyze Sn-based PSC. This simulator is a sophisticated and practical numerical modeling tool made to help understand and make sense of the real workings of solar systems. In contrast to GVPDM and Silvaco, they are complicated & sluggish and demand additional time and processing resources, SCAPS software is frequently used for studying PSCs because it is accurate and fast, yielding dependable results quickly. All SCAPS-1D simulation calculations, however, used the light intensity of the Air mass (AM) 1.5 light spectrum at 300 K. The e- and hole densities have been determined employing the continuity and Poisson equations shown below37,38,39.

Details of all terms used in the above equations:

\(\:\phi\:\), q symbolized potential & charge, n(x), \(\:{n}_{t}\left(x\right)\), Gn, Jn, & Rn symbolized concentration, trap concentration, generation rate, Current density & recombination rate of an e−. Similarly, p(x), \(\:{p}_{t}\left(x\right)\), Gp, Jp & Rp symbolized concentration, trap concentration, generation rate, Current density & recombination rate of hole. \(\:\epsilon\:\) signified the dielectric permittivity of the material,\(\:{\:N}_{A}^{-}\left(x\right)\) & \(\:{N}_{D}^{+}\left(x\right)\) signified the acceptor & donor density.

An n-i-p planar structure of PSC is presented in Fig. 1, with gold (Au) serving as the back contact, PTAA as the HTL, FASnI3 as the active layer, SnS2, TiO2, and metal-doped Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 as the ETLs, and fluorine tin oxide (FTO) as the front contact glass. This PSC-described structure is employed in the initial simulation. Table 1 displays the initial configuration of input parameters, which were gathered from theoretical and practical research of high impact. The work functions of the front (FTO) and back layers (Au) are − 4.1 eV and − 5.0 eV, respectively. In order to avoid charge carriers from recombination and improve charge transportation, ETL and HTL provide a pathway to move e- and holes from the active layer to their corresponding electrodes and enter the external circuit through the metal connectors. Here, we optimize the device using several ETLs, and Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 ETL yields the optimum result.

Findings & discussions

Energy level diagram (EBD) of Sn-based PSC device

This EBD illustrates the band alignments of the FASnI3 layer, HTL, ETL, and other layers within the device structure of a tin-based PSC. The FASnI3 layer is the intrinsic (i) section of the n-i-p structure, which is typical of PSCs, as shown in the diagram. The graphic illustrates the spatial arrangement of several layers and their electronic energy levels by plotting position (µm) along x-axis and energy (eV) along y-axis. Effective electron and hole transport is ensured by the right alignment, which also reduces recombination and energy losses. By using the different ETLs with PTAA as HTL, Fig. 2 shows the EBDs for three distinct device configurations. The device with ETL Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 obtains a PCE of 32.22% after simulation, as shown in Fig. 2(a). The device with ETL SnS2 shown in Fig. 2(b) achieves a PCE of 27.64%. Additionally, the device using ETL TiO2 obtains a PCE of 27.04%, as shown in Fig. 2(c).Therefore, the optimum choice for the transport layers in our optimized device design are PTAA (HTL) and a metal doped Chalcogenide Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 as ETL.

Consequences of variations in FASnI3 layer thickness

PSCs functionality primarily reliant on the thickness of the active layer. Key performance attributes of the PSC are affected by variations in the active layer’s thickness because of variations in light absorption, carrier collecting efficiency, and recombination losses, as presented in Fig. 3(a-d). An increasing thickness of the active layer, which ranges from 0.1 to 1.0 μm in steps of 0.1 μm, increases light absorption, especially at longer wavelengths where more e-h pairs are produced, leading to increased PCE and JSC of the PSCs. As the perovskite layer deepens, the FF may drop because the device’s series resistance (RS) raises due to the recombination of additional charge carriers. VOC is less sensitive to variations in thickness than the JSC. However, with larger layers, increased recombination could somewhat lower or stable the VOC.

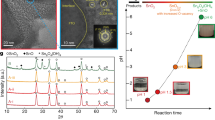

In this section, we looked at the active layer thickness variations for several ETL combinations, including SnS2, TiO2, and Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2.The top-performing ETL metal doped Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 combination with PTAA as HTL demonstrates that the exceptional performance of PCE grows from 15.28 to 32.216% as thickness increases, as presented in Fig. 3(a). The corresponding values for VOC, JSC, and FF range from 1.25 to 1.276 V, 14.37 to 30.83 mA.cm− 2, and 84.92 to 81.86%, as presented in Fig. 3(b, c,d). The best PCE for other ETLs, such SnS2 and TiO2 were 27.64 & 27.037%, VOC 1.1230 & 1.099 V, and JSC 30.836 mA.cm− 2 for both at thickness 1 μm and FF reaches its maximum values of 83.56% at lower thickness, as shown in Fig. 3(a-d).

Consequences of variations in ETL layer thickness

The effectiveness of PSCs is strongly hampered by the thickness of the ETL. While obstructing holes, the ETL is in charge of removing electrons from the active layer and moving them to the electrode. To detect its impact on the solar cell, the ETL thickness changes between 0.01 and 0.05 μm, as depicted in Fig. 4(a-d). A thicker ETL encourages more e-h recombination, which raises resistance and lowers PCE. It also decreases light transmission to the active layer because of higher optical losses, which lowers JSC. Thicker ETL reduces the device’s VOC and marginal FF by increasing resistive and recombination losses. For our device simulation, we used three distinct ETL materials: Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2, SnS2, and TiO2. Over the thickness range of 0.01 μm to 0.05 μm, the PCE for all three ETL materials either stays essentially constant or slightly declines. However, the ETL material affects the absolute PCE values.

The performance of Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 is better due to its faster charge mobility, better energy level alignment with the active layer, and a lower defect density, which results in more effective electron extraction and less recombination losses than SnS2, and TiO2. The Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 ETL device PCE ranges from 32.52 to 32.216% as thickness increases from 0.01 to 0.05 μm, while the VOC, JSC, and FF vary from 1.2927 to 1.2762 V, 30.838 to 30.835 mA.cm− 2, and 81.60 to 81.86%, respectively. At a thickness of 0.01 μm, the best results were obtained with ETL SnS2 and TiO2 are PCE 27.65% & 27.037%, VOC 1.1245 V & 1.1007 V, JSC 30.838 mA.cm− 2 for both, and FF 79.74% & 79.65%, respectively, as presented in Fig. 4(a-d). As an ETL material, Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 performs better than SnS2 and TiO2, offering the best efficiency because of its superior charge transport characteristics and reduced recombination losses.

Consequences of variations in HTL layer thickness

The effectiveness of PSCs is significantly reliant on the thickness of the HTL. To reduce recombination, the HTL must simultaneously block e− s remove holes from the active layer, and move them to the electrode. The impact of HTL thickness (varies from 0.01 to 0.08 μm) on the solar cell is demonstrated in this section using three distinct ETL materials Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2, SnS2, and TiO2, as presented in Fig. 5(a-d). This finding implies that a relatively constant trend in JSC may have resulted from a rise in charge recombination, even if the device’s charge transport characteristics increased. Voc rises as carrier collection improves with increasing HTL thickness. As a result, PCE shows an increasing tendency. Figure 5(a-d) shows that VOC, JSC, FF, and PCE levels were not affected or significantly improved for any of the ETLs when the HTL PTAA thickened. For additional numerical analysis, an HTL thickness of 0.08 μm has been preserved for all ETL devices. With a VOC of 1.2762 V, JSC of 30.83 mA.cm− 2, FF of 81.87%, and a noteworthy PCE of 32.216%, the Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 ETL device once again demonstrates the greatest performance. As the HTL thickness grows from 0.01 to 0.08 μm, the best PCE for various ETLs, such as SnS2 and TiO2 are 27.64 & 27.037%, VOC 1.1230 & 1.099 V, and JSC 30.836 mA.cm− 2 for both, and FF 79.82 & 79.71%, as presented in Fig. 5(a-d).

Significance of defect density (Nt) vs. thickness variation

In PSCs, the correlation between defect density (Nt) and thickness variation is critical in determining device performance, as presented in contour plots Figs. 6, 7 and 8(a-d) for various ETL Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2, SnS2, and TiO2. Adjusting the thickness from 0.1 to 1 μm in steps of 0.1 μm and the Nt from 1 × 1012 to 1 × 1018 cm− 3 allowed for the observation of the ideal value. The device’s PCE and JSC are improved as the active layer thickness grows because more e-h pairs are created. Non-radiative recombination centers brought forth by high Nt shorten the charge carrier lifespan and increase recombination losses, which lowers the device’s PCE and JSC. Excessively thick and high defect areas lower the device’s VOC by increasing recombination and resistance losses. Because high Nt introduces non-radiative recombination and increased series resistance, which causes a decline in FF, the FF is at its highest at lower thickness and Nt.

The most suitable combination with the Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 and PTAA as ETL & HTL was found after analyzing all three device topologies. When Nt fluctuates between 1 × 1012 to 1 × 1018 cm− 3, the PCE, VOC, and JSC for this combination ranges from 32.22 to 20.0%, 1.2764 to 1.1265 V, and 30.836 to 21.48 mA.cm− 2 as thickness increases from 0.1 to 1.0 μm, presented in Figs. 6, 7 and 8(a-c). Whereas the FF reaches its highest value of 84.93% at lower thickness of 0.1 μm. Additional ETLs, such SnS2, PCE, VOC, and JSC, range from 27.64 to 18.65%, 1.1230 to 1.060 V, 30.836 to 21.43 mA.cm− 2, and FF 83.56% at lower thickness, respectively, as shown in Fig. 7(a-d). Figure 8(a-d) indicates that TiO2 ETL’s PCE, VOC, and JSC decreases from 27.037 to 18.90%, 1.099 to 1.081 V, 30.836 to 21.35 mA.cm− 2, when thickness increases from 0.1 to 1.0 μm and FF attains a maximum values of 83.589% at lower thickness, when Nt fluctuates between 1 × 1012 to 1 × 1018 cm− 3 respectively. By aiming for a low Nt and adjusting the layer thickness for optimal performance, this study helps direct the production and material optimization of PSCs.

Impact of acceptor density (NA) vs. thickness variation

The thickness of the FASnI3 layer and NA have a major contribution to the functionality of the device. To achieve optimum performance, these parameters must be optimized. In order to analyze the impact of these variables on the PV characteristics of the three PSC devices, the FASnI3 thickness was changed from 0.1 μm to 1.0 μm and the NA was changed from 1 × 1012 to 1 × 1018 cm− 3. Figures 9, 10 and 11(a-d) shows the effects of concurrently altering the active layer thicknesses and NA using contour plots for various ETL combinations such that Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2, SnS2, and TiO2. Reduced NA lowers doping levels, which results in poor electric field creation. Ineffective carrier collection lowers carrier drift, which lowers PCE and JSC. The built-in electric field is strengthened, charge separation and carrier drift are improved, and the PSC parameters improve as acceptor density rises. Overly thick layers decrease FF as NA and thickness increase it via increasing recombination and resistance. Increases VOC via improving quasi-Fermi level splitting and intrinsic potential. After examining all three device topologies, the best pairing of the Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 ETL and PTAA HTL was discovered. According to Figs. 9, 10 and 11(a-c), the PCE, VOC, and JSC for this combination at a thickness of 1.0 μm vary from 30.23 to 32.216%, 1.2506 to 1.12762 V, and 30.77 to 30.836 mA.cm− 2 when NA varies between 1 × 1012 to 1 × 1018 cm− 3 respectively. However, with smaller thicknesses of 0.1 μm and NA 1 × 1018 cm− 3, the FF achieves its uppermost value of 84.92%, as shown in Fig. 9(d). At NA of 1 × 1018 cm− 3, other ETLs, including SnS2 and TiO2, reach their maximum PCE of 27.64% and 27.03%, respectively. Consequently, it is preferable to use metal chalcogenide Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 based ETLs for FASnI3 absorber based PSCs as instead of SnS2 and TiO2.

Impact of defect variation at PTAA/FASnI3 interfaces

Interface defects (IDD) at the PTAA/FASnI3 interface have a major influence on charge carrier dynamics and device stability, making it a crucial factor in PSC effectiveness, as presented in Fig. 12(a-d). Here, we use several combinations of ETLs Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2, SnS2, and TiO2 using PTAA as the HTL to optimize three different device structures. An energy barrier caused by high IDD at the HTL/perovskite interface can hinder hole extraction and increase carrier buildup. This increases recombination losses, which lowers the quasi-Fermi level splitting and, therefore, the solar device’s characteristics. A high defect density causes recombination losses and series resistance to rise, which lowers or hardly alters FF. The effects of IDD (which varies from 1 × 1010 to 1 × 1015 cm− 2) on the PV parameters are presented in Fig. 12(a-d).

The PCE, VOC, and JSC decrease from 32.216 to 25.24%, 1.2762 to 1.1613 V, and 30.836 to 26.435mA.cm− 2, as IDD increases from 1 × 1010 to 1 × 1015 cm− 2. FF exhibits stability between these and has value ranges between 81.9 and 82.2% for the Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 ETL and PTAA HTL combination, as shown in Fig. 12(a-d). Other ETLs, such as SnS2 and TiO2, achieve their maximum PCE of 27.64% and 27.037%, respectively, at IDD of 1 × 1010 cm− 2. For FASnI3 absorber-based PSCs, metal chalcogenide Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 based ETLs are therefore preferred over SnS2 and TiO2 due to their superior interface quality and reduced inherent recombination losses.

Significance of defect variation at ETL/FASnI3 interfaces

The overall performance of PSCs is largely determined by the IDD at the ETL/ FASnI3 layer. Here, we optimize three distinct device topologies employing PTAA as the HTL and various combinations of ETLs Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2, SnS2, and TiO2, as seen in Fig. 13(a-d). Because trap states allow for quicker deterioration under operational circumstances, a greater IDD is frequently associated with poor stability. Trap states, which serve as recombination centers, are introduced by increased IDD at the ETL/FASnI3 interface. This results in more non-radiative recombination, and lower charge extraction efficiency, which decreases solar parameters. The PCE, VOC, JSC and FF for the Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 ETL and PTAA HTL decrease from 32.216 to 18.04%, 1.2762 to 0.959 V, and 30.836 to 26.47mA.cm− 2 and 81.86 to 71.02%, when IDD increases from 1 × 1010 to 1 × 1015 cm− 2, as shown in Fig. 13(a-d). Other ETLs, such as SnS2 and TiO2, achieve their maximum PCE of 27.64% and 27.037%, respectively, at IDD of 1 × 1010 cm− 2 and then degraded as IDD increases.

For FASnI3 absorber-based PSCs, metal chalcogenide Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 based ETLs are therefore preferred over SnS2 and TiO2 because it exhibits superior passivation and lattice matching characteristics at the interface with the FASnI3 layer. This reduces the recombination losses imposed on by defect states.

Impact of temperature variation

Material qualities, thermal stability, and interface effects all contribute to the impacts of temperature change on solar cell device parameters. This section examines the impact of temperature changes (from 300 K to 400 K) on FASnI3 based PSCs with different ETL (Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2, SnS2, and TiO2) combinations, as presented in Fig. 13(a-d). As the temperature increases the concentration of intrinsic carriers, which in turn increases carrier recombination and decreases the VOC. The JSC may slightly rise or stay constant with slight temperature changes due to enhanced carrier mobility, while at greater temperatures, the JSC may fall due to increased recombination. Because of increased carrier recombination, higher series resistance in the contacts and transport layers causes degradation in FF as temperature rises. VOC, JSC, and FF fluctuations all add up to a drop in PCE. As temperature increases from 300 to 400 K, the PCE, VOC, and FF for the Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 ETL and PTAA HTL drop from 32.216 to 29.87%, 1.2762 to 1.229 V, and 81.86 to 78.84%, respectively, as seen in Fig. 14(a-d). Other ETLs, such SnS2 and TiO2, decline as the temperature rises after reaching their maximum PCE of 27.64% and 27.037%, respectively, at 300 K. For all ETLs, the JSC value remains constant at 30.83 mA.cm− 2 despite temperature variations; this is because more charge carriers are being generated. Due to the addition of selenium (Se), which increases lattice stability and the ETL’s capacity to sustain performance under thermal stress, Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 performs better than SnS2 and TiO2, making it a better option for high-temperature applications.

J-V & EQE curve

The EQE curve describes the spectrum efficiency and aids in identifying wavelength-specific losses, the J-V curve offers overall electrical performance indicators. The percentage of incoming photons that are transformed into e-h pairs is shown by the EQE curve. The QE curve of a solar cell should ideally be square or rectangular, but reflection losses, recombination, and surface passivation may all influence it. The nature of QE for different wavelengths is examined for the solar cell designs of (FTO/SnS2/FASnI3/PTAA/Au), (FTO/TiO2/FASnI3/PTAA/Au), and (FTO/Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2/FASnI3/PTAA/Au) in order to more accurately identify the accumulation of charge carriers. All three structures exhibit a QE of 100% at 360 nm, as shown in Fig. 15(b). However, in every structural situation, QE starts to drop beyond 800 nm. The external circuit’s inability to absorb high wavelength photons and back surface recombination are the causes of this decline. Figure 15(a) displays the J-V curve for each of the three device architectures. When the VOC was around 1.099 V for TiO2 as ETL, 1.123 V for SnS2 ETL, and 1.2762 V for Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 ETL, all three PSC structures showed a JSC of almost 30.84 mA.cm− 2. In contrast to SnS2 and TiO2 ETL, it demonstrates that the metal chalcogenide ETL-based device structure (FTO/Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2/FASnI3/PTAA/Au) is the optimal option for our device simulation.

Comparative analysis

We have compiled the most recent outputs in Table 2 to compare our suggested lead free Sn-based PSC with an ETL Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 device based on metal chalcogenides. The results of previously published study are listed. Table 2 demonstrates that our simulated findings are significantly better to the previously reported research.

Conclusion

In order to overcome the long-standing issues of oxidation instability and poor compatibility with traditional metal oxide ETLs, this study pioneers the use of Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 as a novel ETL for Sn-based PSCs. The suggested ETL provides outstanding performance under thermal stress in addition to stabilizing the lattice structure by utilizing the special qualities of selenium inclusion. The optimized device structure (Au/PTAA/FASnI3/Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2/FTO) achieves an astounding PCE of 32.22%, along with an impressive VOC of 1.2762 V, FF of 81.87%, and JSC of 30.836 mA.cm− 2 after optimization of various parameters, including active layer thickness, defect densities, and interface engineering. These measurements clearly show that Sn(S0.92Se0.08)2 is a better option than conventional ETLs such as SnS2 and TiO2. This work establishes a new standard for lead-free PSCs by fusing enhanced efficiency with environmental sustainability, demonstrating how material innovation may fully realize the potential of Sn-based PSCs. The results encourage further developments toward scalable, reliable, and environmentally friendly solar technology in addition to addressing present limitations.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Srivastava, P. et al. Theoretical study of perovskite solar cell for enhancement of device performance using SCAPS-1D. Phys. Scr. 97, 125004 (2022).

Rai, S., Pandey, B. K. & Dwivedi, D. K. Modeling of highly efficient and low cost CH3NH3Pb(I1-xClx)3 based perovskite solar cell by numerical simulation. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 100, 109631 (2020).

Verma, A. A. et al. Innovative design strategies for solar cells: theoretical examination of linearly graded perovskite solar cell with PTAA as HTL. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 196, 112401 (2025).

Umar, A. et al. High Power-Conversion Efficiency of Lead-Free Perovskite Solar Cells: A Theoretical Investigation. Micromachines vol. 13 at (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/mi13122201

Afridi, K., Noman, M. & Jan, S. T. Evaluating the influence of novel charge transport materials on the photovoltaic properties of MASnI3solar cells through SCAPS-1D modelling. R Soc. Open. Sci. 11, 231202 (2024).

Bhattarai, S. et al. Numerical investigation of toxic free perovskite solar cells for achieving high efficiency. Mater. Today Commun. 35, 105893 (2023).

Isoe, W. et al. Thickness Dependence of Window Layer on CH3NH3PbI3-XClXPerovskite Solar Cell. Int. J. Photoenergy 1–11 (2020). (2020).

Sinha, N. K., Ghosh, D. S. & Khare, A. Role of built-in potential over ETL/perovskite interface on the performance of HTL-free perovskite solar cells. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 129, 112517 (2022).

Srivastava, S., Singh, A. K., Kumar, P. & Pradhan, B. Comparative performance analysis of lead-free perovskites solar cells by numerical simulation. J. Appl. Phys. 131, (2022).

Jaiswal, R. et al. Numerical study of eco-friendly Sn-based perovskite solar cell with 25.48% efficiency using SCAPS-1D. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 34, 1–17 (2023).

Dureja, T., Garg, A., Bhalla, S., Bhutani, D. & Khanna, A. Double lead-free perovskite solar cell for 19.9% conversion efficiency: A SCAPS-1D based simulation study. Mater. Today Proc. 71, 239–242 (2022).

Abate, A. Stable Tin-Based perovskite solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 1896–1899 (2023).

Jayawardena, K. D. G. I. et al. Approaching the Shockley–Queisser limit for fill factors in lead–tin mixed perovskite photovoltaics. J. Mater. Chem. A. 8, 693–705 (2020).

Chen, M. et al. Lead-Free Dion–Jacobson Tin halide perovskites for photovoltaics. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 276–277 (2019).

Vegiraju, S. et al. Benzodithiophene Hole-Transporting materials for efficient Tin-Based perovskite solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1905393 (2019).

Li, F. et al. A Cation-Exchange approach for the fabrication of efficient Methylammonium Tin iodide perovskite solar cells. Angew Chemie Int. Ed. 58, 6688–6692 (2019).

Jiang, X. et al. Ultra-high open-circuit voltage of Tin perovskite solar cells via an electron transporting layer design. Nat. Commun. 11, 1245 (2020).

Li, T. et al. Metal chalcogenide electron extraction layers for nip -type tin-based perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53713-4 (2024).

Li, W. et al. Addictive-assisted construction of all-inorganic CsSnIBr2 mesoscopic perovskite solar cells with superior thermal stability up to 473 K. J. Mater. Chem. A. 4, 17104–17110 (2016).

Li, T. et al. Alleviating the crystallization dynamics and suppressing the oxidation process for Tin-Based perovskite solar cells with fill factors exceeding 80%. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2308457 (2023).

Kumar, M. H. et al. Lead-Free halide perovskite solar cells with high photocurrents realized through vacancy modulation. Adv. Mater. 26, 7122–7127 (2014).

Li, T., He, F., Liang, J. & Qi, Y. Functional layers in efficient and stable inverted tin-based perovskite solar cells. Joule 7, 1966–1991 (2023).

Noel, N. K. et al. Lead-free organic–inorganic Tin halide perovskites for photovoltaic applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 3061–3068 (2014).

Nie, R. et al. Mixed sulfur and Iodide-Based Lead-Free perovskite solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 872–875 (2018).

Shi, Y., Zhu, Z., Miao, D., Ding, Y. & Mi, Q. Interfacial dipoles boost Open-Circuit voltage of Tin halide perovskite solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 1895–1897 (2024).

Hao, F., Stoumpos, C. C., Cao, D. H., Chang, R. P. H. & Kanatzidis, M. G. Lead-free solid-state organic–inorganic halide perovskite solar cells. Nat. Photonics. 8, 489–494 (2014).

Abdelaziz, S., Zekry, A., Shaker, A. & Abouelatta, M. Investigating the performance of formamidinium tin-based perovskite solar cell by SCAPS device simulation. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 101, 109738 (2020).

Ritu, G., Kumar, R. & Chand, F. Optimization of ITO/SnO2/FASnI3/PCBM/Ag based perovskite solar cell. Mater. Today Proc. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.05.690

Almufarij, R. et al. Improving performance and recombination losses in lead free formamidinium Tin based perovskite solar cells. Mater. Chem. Phys. 307, 128150 (2023).

Reza, M. S. et al. Tuning the hole transport layer in the Ca3SbI3 absorber-based solar cells to improve the power conversion efficiency. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 194, 112250 (2024).

Reza, M. S. et al. Design and optimization of High-Performance novel RbPbBr3-Based solar cells with Wide-Band-Gap S-Chalcogenide electron transport layers (ETLs). ACS Omega. 9, 19824–19836 (2024).

Verma, A. A. et al. Enhancing Efficiency of Lead-Free Cs2TiIxBr6-x Perovskite Solar Cells Through Linear and Parabolic Grading Strategies: Toward 31.18% Efficiency. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. n/a, (2025).

Reza, M. S. et al. A comprehensive investigation involving numerous HTL and ETL layers to design and simulate high-efficiency Ca3AsI3-based perovskite solar cells. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 172, 113647 (2025).

Chowdhury, T., Reo, Y. & Yusoff, A. Sn-Based perovskite halides for electronic devices. Adv. Sci. 9, 2203749 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. PTAA as efficient hole transport materials in perovskite solar cells: A review. Sol RRL. 6, 2200234 (2022).

Nasti, G. & Abate, A. Tin halide perovskite (ASnX3) solar cells: A comprehensive guide toward the highest power conversion efficiency. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1902467 (2020).

Hossain, M. K. et al. SCAPS-1D, and WxAMPS frameworks for design optimization of efficient Cs2BiAgI6-based perovskite solar cells with different charge transport layers. RSC Adv. 12, 34850–34873 (2022). Combined DFT.

Singh, N., Agarwal, A. & Agarwal, M. Numerical simulation of highly efficient lead-free all-perovskite tandem solar cell. Sol Energy. 208, 399–410 (2020).

El-Naggar, A. A. et al. Numerical simulation based performance enhancement approach for an inorganic BaZrS3/CuO heterojunction solar cell. Sci. Rep. 14, 7614 (2024).

Singh, Y. K. et al. Current matching and filtered spectrum analysis of Wide-Bandgap/Narrow-Bandgap Perovskite/CIGS tandem solar cells: A numerical study of 34.52% efficiency potential. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 112300 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2024.112300 (2024).

Verma, A. A. et al. Achieving 31.16% efficiency in perovskite solar cells via synergistic Dion-Jacobson 2D-3D layer design. J. Alloys Compd. 1010, 177882 (2025).

Ke, W. et al. Efficient Lead-Free solar cells based on Hollow {en}MASnI3 perovskites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 14800–14806 (2017).

Singh, A. K., Srivastava, S., Mahapatra, A., Baral, J. K. & Pradhan, B. Performance optimization of lead free-MASnI3 based solar cell with 27% efficiency by numerical simulation. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 117, 111193 (2021).

Tara, A., Bharti, V., Sharma, S. & Gupta, R. Device simulation of FASnI3 based perovskite solar cell with Zn(O0.3, S0.7) as electron transport layer using SCAPS-1D. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 119, 111362 (2021).

Mattaparthi, S., Sinha, D., Bhura, A. & Khosla, R. Design of an eco-friendly perovskite Au/NiO/FASnI3/ZnO0.25S0.75/FTO, device structure for solar cell applications using SCAPS-1D. Results Opt. 12, 100444 (2023).

Vishnuwaran, M., Ramachandran, K. & Sakthivel, P. An augmented lead-free perovskite solar cell based on FASnI3 using V2O5 as HTL. Phys. Scr. 99, 115029 (2024).

Afzal, S. et al. Performance optimization of FASnI 3 based perovskite solar cell through SCAPS-1D simulation. Hybrid advances 7, (2024).

Alqurashi, R. S. Comprehensive investigation of material properties and operational parameters for enhancing performance and stability of perovskite solar cells. Sci. Rep. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67418-7 (2024).

Kaur, J., Sharma, A. K., Basu, R., Gupta, S. & Gahlawat, D. Modelling and Performance Analysis of Non-Toxic MASnI3 Perovskite Solar Cell with 28.93% Efficiency. in First International Conference on Electronics, Communication and Signal Processing (ICECSP) 1–6 (2024). (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICECSP61809.2024.10697999

Mishra, K. P., Pandey, B. K. & Pandey, S. Unveiling the potential of FASnI3 solar cells through advanced charge transport materials: A SCAPS-1D perspective. J. Alloys Compd. 1006, 176283 (2024).

Vincent Mercy, E. N., Srinivasan, D. & Marasamy, L. Emerging BaZrS3 and Ba(Zr,Ti)S3 chalcogenide perovskite solar cells: A numerical approach toward device engineering and unlocking efficiency. ACS Omega. 9, 4359–4376 (2024).

Rahman, M. F. et al. A numerical strategy for achieving efficiency exceeding 32% with a novel Lead-Free Dual-Absorber solar cell using Ca3SbI3 and Sr3SbI3 perovskites. Adv. Photonics Res. N/a, 2400148 https://doi.org/10.1002/adpr.202400148 (2024).

Ali, M. E., Haque, M. M. & Cheragee, S. H. Device modeling and numerical analysis of lead-free MASnI3/Ca3AsI3 based perovskite solar cells with over 38% efficiency. Sol Energy. 288, 113309 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Akash Anand Verma : Original manuscript writing, methodology, software analysis, reviewing and conceptualization, and D.K. Dwivedi: reviewing, editing and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Verma, A.A., Dwivedi, D.K. Revolutionizing environment friendly FASnI3 perovskite solar cells with pioneering selenium doped metal chalcogenide charge transport layer unlocking 32% efficiency. Sci Rep 15, 27473 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93786-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93786-9