Abstract

Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy (LSG) is the most common bariatric procedure worldwide. However, the influence of preoperative factors on weight loss outcomes remains incompletely understood. We investigated the effects of preoperative weight, height, and age on total weight loss percentage (%TWL) following LSG using advanced statistical modeling. 2014 LSG patients were analyzed and stratified by preoperative weight (7 categories: <90 kg to > 160 kg) and age (5 groups: 14–25 to ≥ 56 years). %TWL was calculated at 1 week, 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post-surgery. A Generalized Additive Model (GAM) was used to calculate Adjusted Total Weight Loss percentage (%ATWL), accounting for height and preoperative weight confounding effects. The population (mean age: 38.0 ± 11.4 years, BMI: 42.9 ± 8.2 kg/m²) showed weight-dependent %TWL at 12 months, from 32.2%±10.0% (< 90 kg) to 39.8%±7.5% (> 160 kg) (p < 0.001). GAM-adjusted %ATWL revealed superior outcomes in younger cohorts. The 14–25 and 26–35 year groups had comparable 12-month %ATWL (38.2% vs. 37.0%, p = 0.222), significantly exceeding older groups (p < 0.001). Early postoperative %ATWL (1-week) was similar across ages (4.6–5.7%), with progressive differentiation at 3, 6, and 12 months. Preoperative weight and age significantly influence LSG weight loss outcomes. Younger patients and those with higher pre-op weights achieved greater 12-month %TWL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity has become a global health crisis, with more than one billion people living with overweight or obesity as of 20221,2,3. This rise in obesity prevalence has led to an increase in obesity-related complications, such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, and cerebrovascular disease4,5.

Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy (LSG) has emerged as an effective treatment option for severe obesity, demonstrating significant weight loss6,7,8. Previous studies have suggested that preoperative weight and age may influence weight loss outcomes after metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS)9,10,11. However, the extent of weight loss following LSG can vary considerably among patients, with recent long-term studies revealing significant heterogeneity in clinical responses. Research has shown that while some patients maintain satisfactory weight loss over time, others experience suboptimal clinical response or recurrent weight gain. A recent 13-year follow-up study identified the first postoperative month and the fifth postoperative year as critical periods that may determine long-term clinical outcomes, with significant decreases in excess weight loss particularly observed after the fifth postoperative year12. This variability in outcomes highlights the critical need to better understand the interplay between preoperative weight, age, height, and other potential confounding factors in determining long-term success.

To address these limitations, we used advanced statistical method to calculate an adjusted total weight loss percentage (%ATWL) metric that accounts for the confounding effects of preoperative height and weight. Using a generalized additive model (GAM), we analyzed weight loss patterns. The GAM was fitted for each time point at 1 week and 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post-operatively with age, height, and pre-op weight as explanatory variables and %TWL as the response variable.

Our study aims to examine the effects of preoperative weight, height, and age on both %TWL and %ATWL in patients who underwent LSG at our general surgery clinic between 2013 and 2023. By analyzing data over a 12-month follow-up period, we aim to determine weight loss patterns for various patient subgroups, considering factors such as preoperative weight, age, and height.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective single-center study included a total of 2014 patients who underwent LSG between May 2013 - November 2023 at the Istanbul Aydin University Obesity Surgery Center, Istanbul, Turkey. Eligibility criteria included body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2 or obesity with associated comorbidities (type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, dyslipidemia). Exclusion criteria included: (1) history of previous metabolic and bariatric surgery (re-operations were excluded); (2) active peptic ulcer disease; (3) pregnancy or planning pregnancy within one year; (4) inability to obtain psychiatrist approval; (5) endocrine obesity (Cushing’s syndrome); (6) malignancy (abdominal, bone, or lung cancer).

All patients underwent a comprehensive preoperative evaluation, including anesthetic, endocrine, and psychiatric examinations. Routine preoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed on all patients to identify any underlying gastrointestinal conditions, such as cancer, polyps, or other pathologies, that may contraindicate surgery or require intervention prior to LSG. These examinations provided a comprehensive baseline record of the patients’ gastric health before the surgery.

Weight loss outcomes were analyzed using multiple approaches to account for various factors affecting weight loss trajectories. Postoperative follow-up was conducted at 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. The study protocol was approved by the Istanbul Aydin University Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee Decision No. 77/2024, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Surgical techniques

The standardized surgical technique, including anesthetic protocol, patient positioning, and trocar placement, was performed according to our previously published methods13. Briefly, patients received 3 mg intravenous midazolam before surgery. During induction, 200 mg 1% propofol, 500 µg/kg rocuronium, 1 mg/kg methylprednisolone, 1 mg/kg fentanyl, 10 mg metoclopramide, 20 mg hyoscine-n-butyl bromide, 50 mg ranitidine, 100 mg tramadol and 2 g paracetamol were administered. Following induction, patients were placed in the reverse Trendelenburg position with their legs in abduction. The surgical team positioning included the surgeon between the patient’s legs, assistant surgeon on the right side, and operating room nurse on the left side. An 11 mm camera port was placed to the left of the midline, approximately 10–12 cm below the xiphoid process, without establishing pneumoperitoneum. CO2 insufflation was initiated to achieve and maintain an intra-abdominal pressure of 14–15 mmHg. Two additional ports were placed on the right side of the abdomen: one 5 mm port and one 12 mm port. A third 5 mm port was placed on the left side of the abdomen. Under camera guidance, a bilateral transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block was performed using Petit’s triangle as an anatomical landmark. Each side of the abdomen was infiltrated with 20 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine hydrochloride solution, equivalent to 100 mg of bupivacaine per side.

The greater curve of the stomach was dissected using LigaSure™ (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). The stomach was dissected and mobilized, starting from the pylorus to the hiatus. The esophagus was carefully mobilized and retracted within the diaphragmatic hiatus, allowing for clear visualization of the right and left crura of the diaphragm. The esophageal hiatus was narrowed using 2 − 0 silk with a Z suture, ensuring an approximately 0.5 cm gap between the crural fibers and the esophageal wall. A 36 F orogastric bougie was passed through the esophagocardial junction to ensure no stenosis was present. The gastric sleeve procedure was initiated 2 cm above the pylorus using Tri-Staple™ (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). During resection, patients received 20 mg tenoxicam and 8 mg ondansetron. After completing the gastric transection, a single suture omentopexy (2 − 0 silk) was performed between the lateral side at the level of the gastrocolic ligament and the stomach incisura angularis. A 10 mm soft silicone drain was placed next to the remaining stomach.

Postoperatively, patients received 0.5 mg/kg pethidine hydrochloride. Within the first 12 h after surgery and on the first postoperative day, patients were given 20 mg tenoxicam twice a day, 50 mg tramadol four times a day, and 1 g paracetamol three times a day, with additional tramadol administered when necessary. Drains were removed on the first postoperative day. At discharge, oral paracetamol syrup was prescribed for analgesia and discontinued after the 7th postoperative day.

Weight loss patterns

Weight loss patterns were analyzed using a systematic approach to evaluate 1 week and 1, 3, 6, and 12 months outcomes. Total weight loss (%TWL) was defined as the primary outcome measure and calculated as [(preoperative weight - current weight) / preoperative weight] × 100. An Adjusted Total Weight Loss percentage (%ATWL) was calculated to account for potential confounding effects of age, height, and preoperative weight on weight loss trajectories.

Patients were stratified into seven preoperative weight categories (< 90, 90–100, 100–110, 120–130, 140–150, 150–160, > 160 kg) to analyze weight loss trajectories across different baseline weights. Age stratification includes five groups (14–25, 26–35, 36–45, 46–55, ≥ 56 years) to evaluate age-specific response patterns.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Python (Version 3.12.4) in Jupyter Lab (Version 4.2.5). The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. For between-group comparisons, independent t-tests were used for normally distributed data and Mann-Whitney U tests for non-normally distributed data. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post-hoc tests were employed to compare outcomes across age groups. The statistical significance of weight loss differences between groups was evaluated using pairwise comparisons, with p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method.

Weight loss patterns were conducted using a systematic approach to evaluate 1 week and 1, 3, 6, and 12 months outcomes. The combined analysis approach allowed for comprehensive assessment of weight loss trajectories while accounting for potential confounding factors and ensuring robust statistical validation of observed differences between groups.

To adjust for the potential confounding effects of height and pre-op weight on total weight loss, we calculated an adjusted total weight loss percentage (%ATWL) using a Generalized Additive Model (GAM) in Python. The GAM was fitted for each time point (1 week, 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post-surgery), with age, height, and pre-op weight as explanatory variables and TWL percentage as the response variable. The partial dependence of height and pre-op weight on TWL was calculated using the GAM, and the effects of these confounding variables (height and pre-op weight) were then removed from the original TWL percentage to obtain the ATWL percentage. This adjustment allowed for a more accurate comparison of weight loss across different age groups by accounting for the potential confounding effects of height and pre-op weight. The %ATWL was then used in subsequent analyses, including one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests, to determine if there were significant differences in weight loss between age groups.

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise specified. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. A power analysis was conducted using the effect sizes, a desired statistical power of 0.95, and a significance level (α) of 0.05, confirming adequate sample sizes for detecting clinically meaningful differences at each time point.

Results

Baseline characteristics

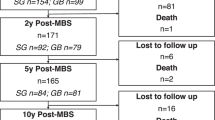

A total of 2,014 patients underwent MBS at our institution from February 2013 to November 2023. The mean age was 38.0 ± 11.4 years, with preoperative measurements showing mean height 167.1 ± 9.2 cm, weight 120.3 ± 27.3 kg, and BMI 42.9 ± 8.2 kg/m². The study population consisted of females (73.5%) and males (26.5%). Common comorbidities included diabetes mellitus (34.5%), hypertension (31.1%), sleep apnea (34.5%), osteoarthritis (13.1%), dyslipidemia (6.3%), and coronary artery disease (2.3%) (Table 1).

Analysis of TWL% over time for various preoperative weight groups

Figure 1 demonstrates the progression of %TWL across different preoperative weight categories over a 12-month postoperative period. Preoperative weight appeared to influence the magnitude of %TWL, with a general trend toward higher %TWL achievement in patients with greater initial weights. At 12 months post-surgery, patients with preoperative weights < 90 kg showed the lowest %TWL (32.2% ± 10.0%), while higher preoperative weight categories achieved greater %TWL, ranging from 36.5 to 39.9%. This trend was particularly evident in patients weighing > 120 kg preoperatively, who consistently achieved %TWL > 38% at 12 months. All weight cohorts show rapid weight loss patterns between 1 and 3 months post-surgery, followed by a gradual deceleration between 6 and 12 months.

Total weight loss percentage (%TWL) trajectories following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy stratified by preoperative weight categories. Line graphs showing progression of %TWL at 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months post-surgery across different preoperative weight categories: (A) < 90 kg, (B) 90–100 kg, (C) 100–110 kg, (D) 110–120 kg, (E) 120–130 kg, (F) 130–140 kg, (G) 140–150 kg, (H) 150–160 kg, (I) > 160 kg, and (J) all patients combined. Data points represent mean values with error bars indicating standard deviation.

Total weight loss (kg) and postoperative weight at 12 months stratified by preoperative weight categories

Figure 2 illustrates the 12-month postoperative weight outcomes and total weight loss across nine preoperative weight categories. Analysis revealed a consistent pattern of increasing postoperative weight with higher preoperative weight categories, ranging from 57.4 ± 8.5 kg in the < 90 kg group to 106.4 ± 16.5 kg in the > 160 kg group. Total weight loss at 12 months demonstrated a similar progressive increase, from 27.3 ± 8.5 kg in the lowest weight category to 70.5 ± 15.4 kg in the highest weight category. Statistical analysis showed significant differences between most adjacent weight categories (p < 0.01 to p < 0.0001). Groups separated by larger weight intervals demonstrated particularly strong significance (p < 0.00001). The comprehensive statistical comparisons depicted by the significance bars demonstrated that heavier preoperative weight categories achieved greater total weight loss while maintaining proportionally higher postoperative weights.

Postoperative weight outcomes and total weight loss at 12 months stratified by preoperative weight categories. Bar graph illustrating mean postoperative weight (kg) at 12 months across nine preoperative weight categories (< 90 kg to > 160 kg). Error bars represent standard deviation. Horizontal bars with p-values indicate statistical significance between groups. The table below displays precise values for postoperative weight and total weight loss at 12 months for each weight category.

Association between preoperative weight and 12-Month total weight loss percentage

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between preoperative weight and %TWL at 12 months post-surgery. The data reveals a clear trend of increasing weight loss percentage as the preoperative weight increases. Analysis of 2014 patients demonstrated a positive correlation between preoperative weight and %TWL at 12 months post-surgery. Patients with preoperative weight < 90 kg achieved the lowest %TWL (32.2% ± 10.0, with significantly lower outcomes compared to all other groups (p < 0.01 to p < 0.001). Those > 160 kg experienced the highest %TWL (39.8% ± 7.5). These findings suggest that preoperative weight significantly influences post-surgical weight loss outcomes, with higher pre-op weights associated with greater %TWL at 12 months.

Association between preoperative weight and total weight loss percentage at 12 months post-laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Bar graph illustrating mean total weight loss percentage (%TWL) at 12 months across nine preoperative weight categories (< 90 kg to > 160 kg). Error bars represent standard deviation. Horizontal bars with p-values indicate statistical significance between groups. The table below provides %TWL values and standard deviations for each preoperative weight category.

Analysis of preoperative weight and height by age groups

In Fig. 4A, pre-operative weight analysis revealed that mean weights ranged from 119.2 kg in the 14–25 age group to 123.8 kg in the 56 + age group. Significant differences in weight were observed between the youngest and oldest cohorts (14–25 vs. 56+, p < 0.05) and between middle-aged and older adults (36–45 vs. 56+, p < 0.05).

Comparison of preoperative weight and height measurements across different age groups. (A) Bar graph illustrating mean preoperative weight (kg) across five age categories (14–25, 26–35, 36–45, 46–55, and 56 + years). (B) Bar graph showing mean preoperative height (cm) across the same age categories. Error bars represent standard deviation. Horizontal bars with p-values indicate statistical significance between age groups.

In Fig. 4B, height measurements demonstrated a gradual decreasing trend with advancing age, from 168.3 in the 14–25 age group to 165.5 cm in the 56 + group. Statistically significant differences in height were found between between the 14–25 age group and both the 46–55 and 56 + groups (p < 0.05 for both comparisons), as well as between the 26–35 and 56 + groups (p < 0.05).

%ATWL analysis using GAM

To adjust for the potential confounding effects of height and pre-op weight on total weight loss, we calculated an ATWL percentage using a GAM. The GAM was fitted for each time point (1 week and 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post-surgery), with age, height, and pre-op weight as explanatory variables and ATWL percentage as the response variable.

The partial dependence of height and pre-op weight on ATWL was calculated and subtracted from the original TWL percentage to obtain the ATWL percentage. This adjustment allowed for a more accurate comparison of weight loss across different age groups by accounting for the potential confounding effects of height and pre-op weight. The %ATWL was then used in subsequent analyses, including one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests, to determine if there were significant differences in weight loss between age groups.

Age-Dependent patterns in %ATWL: longitudinal analysis

Figure 5 illustrates %ATWL distribution and mean trends across age groups through box plots and trend lines, demonstrating an age-dependent weight loss pattern.

Age-dependent patterns in adjusted total weight loss percentage (%ATWL) following LSG. Box plots illustrating distribution of %ATWL across five age groups (14–25, 26–35, 36–45, 46–55, and 56 + years) at different postoperative time points:(A) 1 week, (B) 1 month, (C) 3 months, (D) 6 months, and (E) 12 months. Blue boxes represent interquartile range, horizontal lines indicate median values. Green dotted line depicts the mean trend across age groups.

Figure 5A and B present early postoperative outcomes (1 week and 1 month), showing similar box plot distributions with %ATWL ranging from 4.6 to 5.7%. The mean trend line reveals higher values in younger groups (14–25 and 26–35 years), with significant differences compared to older cohorts (p < 0.05).

Figure 5C shows 3-month outcomes with widening box plot distributions (range: 13.6–17.6%). The mean trend line demonstrates comparable outcomes between 14 and 25 and 26–35 age groups (17.5% and 17.6%, p = 0.749), both significantly exceeding older groups’ performance (p < 0.01).

Figure 5D depicts 6-month outcomes, with box plots showing increased variability and %ATWL (range: 15.9–22.5%). The downward slope of the mean trend line emphasizes the age-dependent pattern, with 14–25 years achieving peak values (22.5%).

Figure 5E demonstrates 12-month outcomes through box plots showing the widest distribution (27.7–38.2%). The mean trend line maintains the age-dependent pattern, with comparable outcomes between the two youngest cohorts (38.2% vs. 37.0%, p = 0.222) and significant differences versus older groups (p < 0.001).

This study revealed significant patterns in LSG outcomes across preoperative weight and age categories. Analysis of %ATWL demonstrated superior outcomes in younger patients (14–25 years), emphasizing the importance of both age and preoperative weight as key determinants of LSG outcomes.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we analyzed the effects of preoperative weight, height, and age on the %TWL and %ATWL in patients who underwent LSG at our institution between 2013 and 2023. Our findings demonstrate that preoperative weight and age significantly influence weight loss outcomes, with younger patients and those with higher pre-op weights achieving greater %TWL at 12 months post-surgery.

Our analysis of %TWL following LSG showed increasing weight loss, with the highest %TWL at 12 months post-surgery across all preoperative weight categories, consistent with previous studies14. Higher preoperative weights were associated with greater %TWL, indicating that pre-op weight is a key factor in post-surgical weight loss. This finding aligns with Sczepaniak et al., who reported that pre-op weight was the most important factor in weight loss and predictability of outcomes after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass9. Our study extends these findings to LSG, highlighting the critical role of preoperative weight in shaping post-bariatric surgery weight loss trajectories. These findings align with recent long-term evidence from Verras et al. (2023), whose 10-year follow-up analysis of 490 patients confirmed that excess weight remains a significant predictor of enhanced weight loss outcomes even after a decade15.

In our study, the examination of preoperative weight and height by age groups revealed significant differences, with older patients generally presenting with higher weights and lower heights compared to younger patients. To account for these confounding factors, we calculated a %ATWL using a GAM. The analysis of %ATWL by age groups demonstrated superior weight loss outcomes in the youngest age group (14–25 years) compared to older age categories. This finding aligns with the growing evidence suggesting age-dependent variations in weight loss outcomes following MBS10,11.

A comprehensive study stratifying patients into five age groups (< 30 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years, 50–59 years, and ≥ 60 years) demonstrated significantly higher weight loss in younger patients compared to older individuals at multiple post-operative time points10. This age-related difference can be attributed to several physiological factors. Notably, Pannemans and Westerterp have shown that older individuals typically exhibit a lower basal metabolic rate and reduced physical activity levels, which may contribute to less pronounced weight loss outcomes in this population16. These findings provide a biological basis for the age-dependent variations observed in our study and others10,16,17. The continuation of this age-dependent pattern has been further validated by Verras et al. (2023), whose 10-year follow-up analysis of 490 patients confirmed that younger age remains a significant predictor of enhanced weight loss outcomes even after a decade15, suggesting that these early predictive patterns are maintained long-term.

Beyond demographic factors, the physiological mechanisms underlying weight loss after LSG involve hormonal changes through gastric fundus resection18,19. The gastric fundus is the primary site of ghrelin production, a hormone that regulates appetite and glucose homeostasis. The removal of the gastric fundus during LSG leads to significant reduction in ghrelin levels, contributing to both early metabolic benefits and weight loss over time18. The underlying hormonal changes due to the fundus resection represent an important physiological mechanism supporting postoperative weight loss18. These hormonal changes may contribute to the progressive weight loss patterns observed in our results. This mechanism provides additional context for interpreting our findings regarding postoperative weight loss trajectories.

Our results align with findings from Contreras et al., who found that patients younger than 45 years old lost a greater amount of excess BMI than older patients (≥ 45 years) after MBS10. Similarly, Yoshihiro Nagao et al., in their analysis of 308 patients divided into young (18–29 years), intermediate (30–49 years), and senior (50–68 years) groups, demonstrated that the young group consistently achieved statistically significant higher percentage of excessive weight Loss (%EWL) compared to the intermediate and senior groups at both 6 and 12 months post-surgery11.

However, our findings contrast with those of Woźniewska et al., who found no statistically significant differences between patients < 45 years old and ≥ 45 years old in terms of %TWL during their two-year observation period20. This discrepancy might be attributed to their binary age categorization, which could have masked the more nuanced age-related differences revealed by our five-group analysis. Our study provides a more detailed analysis of age stratification, combined with the use of GAM to adjust for confounding factors, offering a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between age and post-operative weight loss outcomes.

LSG is a non-malabsorptive type of MBS with a lower risk of developing postoperative nutritional deficiencies compared to RYGB, which is a malabsorptive procedure21,22,23. The resection of the gastric fundus during LSG leads to a reduction in parietal cells and decreased intrinsic factor production, which can impair the absorption of key nutrients such as vitamin B12 and iron21,22,24. Recent long-term data demonstrates that by 6 years post-surgery, patients developed significant deficiencies in several micronutrients, particularly ferritin (43.3%, p < 0.001) and vitamin B12 (11.7%, p = 0.019), while iron deficiency (25%, p = 0.625) showed no significant change from baseline21. These nutritional complications can be attributed to multiple factors, including postoperative nausea and vomiting, reduced food intake, and subsequent poor food choices21,25. This understanding emphasizes the importance of regular nutritional monitoring and supplementation in the post-operative management.

While our study focused primarily on weight loss outcomes, it’s important to acknowledge that postoperative complications, particularly staple line leaks, remain a significant concern in sleeve gastrectomy. Recent evidence demonstrates leak rates ranging from 2.2 to 6.46%, representing the second leading cause of mortality after MBS26. Several risk factors have been identified, including smoking, diabetes mellitus, and sleep apnea. Current evidence supports a multimodal approach to leak management, with studies showing success rates of up to 73% with percutaneous drainage and 53.8% with endoscopic stenting, while early detection through measures such as drain amylase monitoring has shown promise in improving outcomes15. While intraluminal endoscopic stenting is utilized for managing staple line leaks at our institution, we identify the need for future prospective studies examining our institutional outcomes regarding leak management strategies. This represents an important future direction, as comprehensive understanding of both weight loss dynamics and complication management is crucial for optimizing patient outcomes in MBS.

Our study has several strengths, including a large sample size, a comprehensive analysis of weight loss outcomes over a 12-month follow-up period, and the advanced analysis using GAM to adjust for potential confounding factors. However, there are also limitations to consider. As a retrospective single-center study, our findings may be subject to selection bias and confounding factors not accounted for in the analysis. Additionally, we did not assess the impact of other potential factors of weight loss outcomes, such as obesity complications, patient’s compliance on dietitian’s instructions and postoperative lifestyle factors, which may have influenced the results. Future prospective studies should consider these factors and incorporate longer follow-up periods to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the determinants of weight loss following LSG.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that preoperative weight and age significantly influence weight loss outcomes following LSG, with younger patients and those with higher pre-op weights achieving greater %TWL at 12 months post-surgery. The use of a GAM to adjust for potential confounding factors allowed for a more accurate comparison of weight loss outcomes across different age groups. These findings highlights the importance of considering both preoperative weight and age when evaluating weight loss outcomes following MBS. The results of this study may help guide patient selection, counseling, and expectation management in clinical practice.

Data availability

All datasets used and/or analyzed in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Obesity and overweight [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 27]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

World Obesity Atlas. World Obes. Fed. [cited 2024 Oct 27]. (2022). [Internet] Available from: https://www.worldobesity.org/resources/resource-library/world-obesity-atlas-2022

Controlling the global. obesity epidemic [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 27]. Available from: https://www.who.int/activities/controlling-the-global-obesity-epidemic

Powell-Wiley, T. M. et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 27];143. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/ (2021). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000973

Artham, S. M., Lavie, C. J., Milani, R. V. & Ventura, H. O. Obesity and hypertension, heart failure, and coronary heart disease— risk factor, paradox, and recommendations for weight loss. Ochsner J. 9, 124–132 (2009).

Monteforte, M. J. & Turkelson, C. M. Bariatric surgery for morbid obesity. Obes. Surg. 10, 391–401 (2000).

Alfadda, A. A. et al. Long-Term weight outcomes after bariatric surgery: A single center Saudi Arabian cohort experience. J. Clin. Med. 10, 4922 (2021).

Kuno, T., Tanimoto, E., Morita, S. & Shimada, Y. J. Effects of bariatric surgery on cardiovascular disease: A concise update of recent advances. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 6, 94 (2019).

Sczepaniak, J. P. et al. A simpler method for predicting weight loss in the first year after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. J. Obes. 2012, 1–5 (2012).

Contreras, J. E., Santander, C., Court, I. & Bravo, J. Correlation between age and weight loss after bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 23, 1286–1289 (2013).

Nagao, Y. et al. Age impact on weight loss and glycolipid profile after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: experience with 308 consecutive patients. Surg. Endosc. 28, 803–810 (2014).

Lampropoulos, C. et al. Critical Time Points for Assessing Long-Term Clinical Response After Sleeve Gastrectomy-A Retrospective Study of Patients with 13-Year Follow-Up. Obes Surg. ; (2025).

Buyukasik, S., Kankaya, B., Altundal, Y. E., Ozgul, M. & Alis, H. Exploring the Gender-Specific impact of intraperitoneal bupivacaine on early postoperative pain in sleeve gastrectomy. J. Laparoendosc Adv. Surg. Tech. 33, 1040–1046 (2023).

Diamantis, T. et al. Review of long-term weight loss results after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. Off J. Am. Soc. Bariatr. Surg. 10, 177–183 (2014).

Verras, G-I. et al. Outcomes at 10-Year Follow-Up after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, biliopancreatic diversion, and sleeve gastrectomy. J. Clin. Med. 12, 4973 (2023).

Pannemans, D. L. E. & Westerterp, K. R. Enegy expenditure, physical activity and basal metabolic rate of elderly subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 73, 571–581 (1995).

Sugerman, H. J. et al. Effects of bariatric surgery in older patients. Ann. Surg. 240, 243–247 (2004).

Kehagias, D. et al. The role of the gastric fundus in glycemic control. Hormones 22, 151–163 (2023).

Sharma, G., Nain, P. S., Sethi, P., Ahuja, A. & Sharma, S. Plasma Ghrelin levels after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in obese individuals. Indian J. Med. Res. 149, 544–547 (2019).

Woźniewska, P. et al. The influence of patient’s age on metabolic and bariatric results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in 2-year observation. BMC Surg. 20, 323 (2020).

Mulita, F. et al. Long-term nutritional deficiencies following sleeve gastrectomy: a 6-year single-centre retrospective study. Przeglad Menopauzalny Menopause Rev. 20, 170–176 (2021).

Ben-Porat, T. et al. Nutritional deficiencies after sleeve gastrectomy: can they be predicted preoperatively? Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. Off J. Am. Soc. Bariatr. Surg. 11, 1029–1036 (2015).

Gehrer, S., Kern, B., Peters, T., Christoffel-Courtin, C. & Peterli, R. Fewer nutrient deficiencies after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) than after laparoscopic Roux-Y-gastric bypass (LRYGB)-a prospective study. Obes. Surg. 20, 447–453 (2010).

van Rutte, P. W. J., Aarts, E. O., Smulders, J. F. & Nienhuijs, S. W. Nutrient deficiencies before and after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. 24, 1639–1646 (2014).

Snyder-Marlow, G., Taylor, D. & Lenhard, M. J. Nutrition care for patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for weight loss. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 110, 600–607 (2010).

Verras, G-I. et al. Risk factors and management approaches for staple line leaks following sleeve gastrectomy: A Single-Center retrospective study of 402 patients. J. Pers. Med. 13, 1422 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.K. Conceptualization (lead) - project administration (lead) - supervision - investigation - review and editing (equal). S.B. Investigation - review and editing (equal). Y.E.A. Data acquisition – formal analysis – visualization - review and editing (equal). M.O. Formal analysis – visualization - review and editing (equal). A.E. Data acquisition - review and editing (equal)P.R. Data acquisition - review and editing (equal)E.G. Data acquisition - review and editing (equal)H.A. Conceptualization (supporting) - project administration – supervision. All authors reviewed and approved the final article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kankaya, B., Buyukasik, S., Altundal, Y.E. et al. Weight loss dynamics after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a retrospective single center analysis with age and preoperative weight stratification. Sci Rep 15, 8771 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93826-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93826-4