Abstract

Student attrition and academic failure remain pervasive challenges in education, often occurring at substantial rates and posing considerable difficulties for timely identification and intervention. Learning management systems such as Moodle generate extensive datasets reflecting student interactions and enrollment patterns, presenting opportunities for predictive analytics. This study seeks to advance the field of dropout and failure prediction through the application of artificial intelligence with machine learning methodologies. In particular, we employed the CatBoost algorithm, trained on student activity logs from the Moodle platform. To mitigate the challenges posed by a limited and imbalanced dataset, we employed sophisticated data balancing techniques, such as Adaptive Synthetic Sampling, and conducted multi-objective hyperparameter optimization using the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II. We compared models trained on weekly log data against a single model trained on all weeks’ data. The proposed model trained with all weeks’ data demonstrated superior performance, showing significant improvements in F1-scores and recall, particularly for the minority class of at-risk students. For example, the model got an average F1-score across multiple weeks of approximately 0.8 in the holdout test. These findings underscore the potential of targeted machine learning approaches to facilitate early identification of at-risk students, thereby enabling timely interventions and improving educational outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High dropout and failure rates are significant challenges in the educational domain, affecting a wide range of courses across various disciplines. These rates can vary drastically, from 30 to 80%, depending on the region, institution, and specific course type1,2,3,4,5,6. In courses like programming, usually offered in the early years of college, students often struggle with abstract thinking and complex problem-solving, leading to higher dropout rates7. Similar challenges are seen in other difficult subjects, especially in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields like mathematics and engineering. While various factors such as socio-economic conditions and cognitive and metacognitive skills also play a role, the material’s high cognitive load and difficulty are significant barriers to successful learning8.

Various pedagogical strategies have been proposed to address these challenges, emphasizing active student engagement in various educational activities. Research suggests that these strategies are more effective when coupled with continuous, formative instructor feedback, which can help to identify and resolve student difficulties early on. Previous studies stress the importance of considering academic and non-academic factors-such as socioeconomic conditions and personal circumstances-when predicting student performance and dropout rates9. By integrating these broader influences, a more comprehensive understanding of students’ struggles can be achieved.

At the same time, there are studies that highlights the potential of learning analytics in identifying at-risk students, particularly in online or distance education contexts10. Their work emphasizes how data-driven analysis of student engagement and activity patterns within learning management systems (LMS) can enable early detection of dropout risks. Early identification is crucial for reducing failure rates, as it allows timely, targeted interventions before students disengage or drop out entirely.

In recent years, predictive modeling using machine learning has emerged as a powerful tool for identifying at-risk students across various courses. These models analyze a wide range of data, including interactions in virtual learning environments, ongoing assessments, and demographic information10,11,12,13,14. By leveraging such data, predictive models can provide insights into which students are at risk and why they are struggling, enabling educators to implement proactive and personalized interventions. For example, some studies demonstrated the effectiveness of early warning systems based on machine learning in improving student retention across multiple disciplines15.

This work builds on the LANSE project, which introduced a cloud-based learning analytics platform to identify students at risk of dropping out or failing in learning management systems16. Due to the limited data available and the need for continuous improvement, we aimed to enhance the system as new data becomes available. Since new courses can present diverse datasets that may challenge the current models, our goal was to develop a more effective predictive model that outperforms the existing ones.

In Experiment 1, we used a method where we trained a model for each course week, the same methodology LANSE’s existing models were trained. In this experiment, we added new features to categorize the logs and used NSGA-II for optimization. We trained the models on the same data as the existing models and then tested both on new data from different courses as the holdout test. This allowed us to compare how well the new and our existing models performed on new data.

In Experiment 2, we compared the one model per week (Experiment 1) method with an approach where we trained a single model using data from all weeks. We used all available data for this comparison, setting aside 30% for holdout testing. For the unique model for all weeks, we added two more features in addition to the log categorization features: one representing the total course duration in weeks and another indicating which week the log entry was from relative to the overall course duration. These features were meant to help the model understand when each log entry occurred during the course.

Given the dataset’s limited size and imbalanced nature, we employed advanced data balancing techniques, such as Adaptive Synthetic Sampling (ADASYN), to improve the model’s accuracy in classifying at-risk students across different course types. Furthermore, a multi-objective hyperparameter optimization approach using the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) was applied to enhance model performance across multiple metrics, addressing some of the limitations of the original models and enabling more precise predictions as data evolves.

This study is driven by core research questions aimed at evaluating different modeling strategies for predicting at-risk students:

-

Question 1: How effectively can machine learning models, trained on limited student log data from Moodle, generalize to predict outcomes in larger and diverse datasets with unseen courses?

-

Question 2: Which features in the student log data are most predictive of success or engagement, and do these features remain equally important across different courses?

-

Question 3: Can the NSGA-II multi-objective optimization algorithm effectively enhance machine learning models’ predictive accuracy and reliability for identifying at-risk students in dropout prediction scenarios?

-

Question 4: How does the predictive accuracy and stability of a single model trained on data from all weeks compare to that of separate models trained on each week?

These research questions are thoroughly addressed throughout the methodology, results, and discussion sections, ensuring a comprehensive analysis aligned with the study’s goals. Each question guides specific aspects of the experimental design and the interpretation of findings.

Related work

Predicting student dropout and academic failure has become a significant area of research, driven by the increasing availability of educational data and advancements in machine learning techniques. Researchers have developed predictive models to identify students at risk of dropping out or failing early in their academic journey by analyzing data from LMS and other educational sources. Numerous studies have explored a variety of machine learning algorithms and data sources to enhance the accuracy and reliability of these predictions across various educational contexts. Recent work has focused on improving the predictive power of machine learning models and addressing challenges such as class imbalance, feature selection, and the integration of non-academic factors such as socio-economic status and behavioral patterns. This section reviews key contributions in the field, emphasizing predictive modeling techniques, the role of LMS data, and the challenges associated with building effective models for dropout prediction.

Machine learning models for predicting dropout

Machine learning models such as logistic regression, decision trees, random forests, and support vector machines have been widely used to predict student dropout and academic performance10,13,14,17. These models often utilize features such as academic grades, attendance records, and demographic information to identify student success or failure patterns. Studies have applied various machine learning algorithms, demonstrating their effectiveness in real-world educational settings18. Recent studies have investigated deep learning and artificial neural networks (ANN) for dropout prediction, showing that ANN models can achieve satisfactory performance in specific scenarios, with an F1-score of 0.76 in student dropout prediction17. However, other cases, such as in19, reported lower performance, where the best-performing model was a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network with an accuracy of approximately 0.57. This study used LSTM and One-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1DCNN). In contrast17, found that an ANN outperformed both Random Forest and decision tree models, suggesting that performance may depend on the dataset and ANN architecture. Predictive models developed using LMS log data have shown promising results, achieving an F1 score of 0.85% with a Random Forest model for predicting dropout in technical courses20. This study demonstrated that LMS logs, including metrics like student participation in assignments and views of teaching materials, can be highly predictive of academic outcomes, providing valuable insights for early intervention. Additionally, recent work highlights the critical role of feature engineering, exploring how learning behaviors extracted from interaction logs can be leveraged to improve prediction accuracy21.

An explainable machine learning approach for dropout prediction in Brazilian schools has been proposed, achieving high recall (up to 72%) and precision (up to 92%) when predicting dropout at various educational stages15. This approach leverages academic data, socioeconomic factors, and temporal features to enhance prediction accuracy, providing insights into student behavior across multiple educational stages.

There is a discernible preference for classical machine learning models, particularly boosting tree algorithms, given their strong empirical performance in tabular datasets. For instance, in22, a comparative analysis of multiple models identified CatBoost as the superior performer, achieving an AUC ROC of 0.77 and a Precision of 0.85. Following a similar methodology, we initially considered a broad range of architectures and subsequently refined our selection based on performance metrics. In our study, CatBoost demonstrated the most robust performance, prompting us to standardize its architecture for further analysis.

Data sources and feature engineering

The success of predictive models largely depends on the quality and variety of data available. Studies have utilized various data sources, including academic records, LMS interactions, and socio-economic and psychological factors12,23. In particular, LMS log data has been shown to significantly predict academic achievement across various studies. Research highlights the critical role of LMS log data in predicting student dropout, demonstrating that features such as attendance, forum discussions, and assessments can significantly contribute to the accuracy of machine learning models24. This study utilized algorithms like Naïve Bayes and Support Vector Machine, achieving high prediction accuracy and further emphasizing the utility of LMS data in developing effective early warning systems for at-risk students.

A cluster-based approach was used to analyze student dropout patterns using LMS data, identifying various behavioral profiles of students within an LMS environment, such as login frequency, resource access, and participation in activities25. These profiles provided critical insights into student engagement and were used to cluster students into groups, enabling more tailored interventions to prevent dropout and improve academic performance. The study also underscored the importance of distinguishing different levels of engagement, particularly in large-scale online courses, where student behaviors can vary widely.

A comprehensive meta-analysis on log variables in education was conducted, revealing which specific log variables are most correlated with student performance26. These findings align with our approach of utilizing detailed interaction logs, such as the number of days with/without access, log frequency, and activity types, as key predictors in our model.

Challenges and limitations

One of the primary challenges in developing predictive models for student dropout is the issue of class imbalance, where the number of students who drop out is either high or low, depending on the course type. This imbalance can lead to biased models that perform well overall but poorly in identifying at-risk students. Various techniques, such as Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) and ADASYN, have been employed to address this issue14,27.

In this study, we use ADASYN for resampling and NSGA for hyperparameter search, respectively. The architecture and ADASYN were chosen as they demonstrated the best performance during our hyperparameter search.

While ADASYN and NSGA are effective, they may not always be the most suitable solutions, depending on computational constraints. However, NSGA, like other genetic algorithms, offers flexibility to adapt to these constraints. For instance, mutation strategies can be adjusted to improve exploration, crossover techniques can be optimized, and the number of generations and population size can be reduced to align with available computational resources.

Access to comprehensive student data is often limited, leading to small and constrained datasets. This poses a significant challenge to the generalizability and performance of predictive models. Effective data processing techniques, including feature engineering and model optimization, are essential to mitigate these limitations. One promising approach is using genetic algorithms for search optimization, including hyperparameter tuning. These algorithms have shown significant potential in enhancing model accuracy and generalizability by systematically searching through the hyperparameter space to find optimal configurations10. Table 1 summarizes the studies presented here.

While the dataset utilized in this study included 567 unique student-course instances across 23 courses, its limited volume poses significant constraints on the model’s generalizability. Although the dataset covers a variety of courses, the relatively small number of student-course instances restricts the model’s ability to capture broader patterns of student engagement and dropout behavior. This limitation may affect the robustness of the findings, as a larger dataset would provide a more representative distribution of learning behaviors across different academic contexts. Additionally, the dataset does not include longitudinal data or information from asynchronous learning formats, which could offer deeper insights into how student engagement evolves over time. Future studies should aim to validate the proposed model using larger datasets with more extensive student participation, enabling a more comprehensive assessment of its adaptability and effectiveness.

Moreover, external factors such as socioeconomic status, teaching quality, and student motivation, which are known to significantly influence dropout rates15,28, were not included in this study. Our choice to rely solely on data from online learning platforms (e.g., Moodle logs) was intentional, aiming to maximize the applicability of our approach for institutions with minimal resources. This decision allows any institution with access to basic LMS data to adopt our framework without additional data collection burdens. However, we acknowledge that incorporating these external variables, when available, could further refine the model’s predictions, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the factors contributing to student dropout.

Methodology

This section outlines the methodology adopted in this study, which builds upon the LANSE project16, encompassing data preprocessing, model training, and hyperparameter optimization using the NSGA-II29. The goal was to predict student dropout and course failure by leveraging a complex search space that includes model selection, feature selection, hyperparameter tuning, normalization, and oversampling settings. Two separate experiments were conducted, using different sets of training and test data. The methodology follows a structured process, from data collection to model evaluation as illustrated in Fig. 1.

The methodology consists of several key stages. The first step, data processing, involves the cleaning and formatting raw data to ensure consistency and readiness for analysis. Next, feature engineering is applied to transform or create new features that capture meaningful patterns in the data, improving model accuracy. The optimization process encompasses feature selection to reduce dimensionality and focus on the most relevant variables, hyperparameter tuning to fine-tune the model’s performance, and model selection, which involves comparing different algorithms to identify the best-suited one for the task. Resampling techniques such as SMOTE and ADASYN address the class imbalance issue. Finally, the model’s performance is rigorously evaluated using appropriate metrics, and further fine-tuning is performed to ensure robustness and accuracy.

Data description and preprocessing

The dataset utilized in this study includes 567 unique student-course instances, with students enrolled in 23 different courses across various disciplines. Initially, all courses were set to 15 weeks, the most common course length. However, this rigid structure limited the flexibility of our models in generalizing to courses with different durations. To address this issue, we normalized each student’s progress based on the percentage of the course completed, allowing the model to be applied across courses of varying lengths.

The dataset consists of 25 features, primarily derived from student interaction logs on the LMS. These features capture diverse aspects of student engagement, activity, and course progression. A summary of these features and their descriptions is provided in Table 2. Given the limited size of our dataset, overfitting was a major concern, especially when training more complex models. To mitigate overfitting, we applied cross-validation with five folds (k = 5) during training30 and implemented early stopping criteria in models such as CatBoost31. Additionally, oversampling techniques, like ADASYN32, were employed to address the issue of class imbalance, and we experimented with various normalization techniques33 to standardize the feature values.

Our study utilized datasets from 23 unique courses across various disciplines in both experiments. The datasets for Experiment1 and Experiment2 shared similar structures, including the number of unique students and courses and the distribution of student outcomes. However, Experiment2 introduced two new features for course progress and length.

Table 3 provides a detailed summary of the dataset used in both experiments, including the number of student-course instances, unique students, unique courses, and the percentage of students who were approved or failed in both the training and test sets.

As observed in Table 3, both experiments involved training sets of 3871 instances and test sets of 1660 instances, ensuring consistent data sizes across both experiments. The course categories were grouped into four main categories: Programming and Algorithm Courses, Structures and Data Science Courses, Philosophy and Ethics Courses, and Specialized Elective Courses. The distribution of these categories in both experiments’ training and test sets is visualized in Figs. 2 and 3.

Multi-objective optimization with NSGA-II

The NSGA-II has emerged as a powerful multi-objective optimization tool across various domains, including educational data mining, where balancing competing objectives such as precision and recall is crucial. Originally proposed as an optimization algorithm, NSGA-II’s strength lies in its ability to effectively identify a diverse set of Pareto-optimal solutions while maintaining computational efficiency, essential for optimizing machine learning models over large datasets29.

In this study, NSGA-II was employed to optimize model selection and hyperparameters. It leveraged its multi-objective capabilities to balance predictive accuracy for students at risk of dropout with other key performance indicators. Unlike traditional single-objective optimization, NSGA-II allows for simultaneous optimization of multiple conflicting objectives by generating a Pareto front of non-dominated solutions, thus facilitating a more comprehensive exploration of the trade-offs between metrics such as recall and F1-score.

The NSGA-II algorithm integrates several critical components that enhance its robustness and adaptability. Key among these is its fast, non-dominated sorting approach, which organizes solutions into hierarchical layers based on Pareto dominance, allowing for efficient selection of high-quality solutions across generations. The crowding distance within NSGA-II further ensures that solutions are evenly distributed along the Pareto front, avoiding convergence to suboptimal regions and enhancing the diversity of solutions34.

NSGA-II can incorporate an elitist strategy, which retains the best solutions across generations, thereby accelerating convergence and maintaining solution quality, which is particularly useful in high-dimensional search spaces. This approach is especially advantageous in optimizing machine learning models, where balancing objectives often leads to a complex solution landscape35. The algorithm’s ability to handle combinatorial optimization problems effectively, as outlined in both Yusoff and Verma’s reviews, supports its application in our study, where multi-dimensional feature spaces and hyperparameter tuning are key challenges.

Optimization strategy

To identify the most effective model configuration, we employed the NSGA-II algorithm29, which enabled a thorough exploration of multiple components within the search space. Model selection began by testing several algorithms: Random Forest, XGBoost, CatBoost31, k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), Logistic Regression, and Naive Bayes. Preliminary testing on an AutoML platform was used to select the architectures for inclusion in our optimization search for model selection. In addition to model selection, NSGA-II guided the selection of optimal feature combinations from a set of 23 features and fine-tuned essential hyperparameters like learning rate, number of estimators, and tree depth for boosting models. Normalization techniques, including robust, standard, and min-max scaling, were evaluated to ensure proper scaling across features33. To address class imbalance effectively, we applied ADASYN32, which was particularly complementary to CatBoost’s strengths, improving its performance on the minority class.

Statistical and distance measures for model evaluation

We employed two statistical tests to assess the alignment between the train and test datasets: the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) and Mann-Whitney U tests. These metrics serve different purposes in evaluating the consistency between distributions:

The KS test is a non-parametric procedure to determine whether two samples originate from the same population. It achieves this by measuring the maximum vertical distance between the empirical distribution functions of the two samples, which represents the largest deviation between their distributions36. A lower KS statistic and a higher p-value indicate stronger similarity between the datasets, while significant differences (higher KS statistic and lower p-value) suggest potential discrepancies that may impact model performance.

The Mann-Whitney U test is a non-parametric test that examines differences in the central tendency (median) between two independent samples without assuming normality37. A lower U statistic and p-value denote significant differences in central tendencies, which may imply varied dataset characteristics between training and testing sets. Conversely, a higher p-value indicates similarity, suggesting the model is likely to perform consistently across datasets.

The results for both tests are displayed in Table 4.

In interpreting these results, the KS test for Experiment1 shows a KS statistic of 0.069 with an extremely low p-value (\(3.48 \times 10^{-131}\)), indicating a statistically significant distributional difference between the train and test datasets, which suggests that generalizing the model may present challenges. In contrast, Experiment2 yielded a much smaller KS statistic of 0.003 with a p-value of 0.938, indicating no significant difference between the distributions of the train and test sets; this alignment is favorable for generalization. Similarly, the Mann-Whitney U test in Experiment1 revealed a low p-value (\(6.33 \times 10^{-49}\)), signifying a notable difference in central tendencies, which could impact the model’s ability to generalize on unseen data. However, in Experiment2, the high p-value (0.489) suggests no significant difference in central tendencies, supporting the alignment of the train and test sets. Together, these findings indicate that Experiment2 benefits from a more consistent dataset alignment between training and testing, which will likely enhance the reliability and generalizability of model performance.

Model training and evaluation

The dataset was divided across two experiments to evaluate and improve model performance under different configurations. In Experiment 1, 220 unique students were allocated to the training set and 357 to the holdout test set, ensuring the holdout data was distinct from the initial training data used by earlier models. A 5-fold cross-validation30 was applied to assess performance consistency and minimize overfitting.

Experiment 2 introduced week-based features, allowing the model to dynamically adjust based on student progress, and employed a randomized holdout dataset consisting of 30% of the total available data. This randomized split provided a broader assessment of the model’s generalizability, as it represented varying time frames and student engagement patterns.

Initially, models with a distinct model were trained separately for each week (up to week 15). Experiment 2 simplified this by introducing relative week-based features, such as current week / total weeks and total course weeks, which enabled a single model to handle data from courses of different lengths.

After conducting these experiments and extensive optimization, CatBoost was chosen as the final architecture. Its strong performance in cross-validation and holdout tests validated its selection, as CatBoost showed remarkable adaptability to static and dynamic features. CatBoost’s native handling of categorical data and its effective regularization methods minimized overfitting, which proved particularly useful in our imbalanced dataset.

Feature engineering

Feature engineering focused on deriving meaningful features from the LMS interaction logs. These features were related to student engagement and included metrics such as:

-

Log Counts: Total number of logs, weekly logs, daily averages, and specific activity types (e.g., content, system use).

-

Access Patterns: Maximum consecutive days with/without access, days with logs, and average days with logs.

-

Time-to-Event Features: Number of days since the first log, the time difference between consecutive logs, and relative course progression calculated as the ratio of the current week to the total course duration.

Replicability of the study

The methodology proposed in this study can be replicated by following a structured process, including data collection, preprocessing, model training, and evaluation. The dataset consists of student interaction logs extracted from a LMS, capturing access patterns, activity participation, and engagement with course content. Institutions adopting this approach should ensure proper data extraction, anonymization, and structuring to align with the features used in this study. The data should be structured so that each record represents a student-course instance, containing engagement metrics such as total logs, days with access, and course progress, along with the final student outcome (approved or failed). The model training follows the outlined steps, including preprocessing to handle missing values, normalizing features, and applying balancing techniques to address class imbalance. For practical use, the model can be integrated into a system that visualizes student engagement and predictions, like Lanse, allowing educators to monitor and intervene when necessary.

Results

Existing models for comparison

The models used for comparison in this study were previously trained using two well-established machine-learning algorithms: XGBoost and Random Forest. These models developed in an earlier study, were trained on a dataset primarily derived from student activity logs on Moodle platforms. The key features included log counting (the frequency of student interactions) and access patterns (frequency and timing of platform access). These features were designed to capture basic student engagement as predictors for identifying dropout risk. The data and models were organized every week, meaning each week had a corresponding model. A Bayesian search was used to select both model parameters and strategies for handling class imbalance, including implementing the SMOTE.

These models provided valuable benchmarks for evaluating the current study’s approach and were actively deployed in the LANSE cloud application16. Despite their utility, they had several limitations. The feature set was limited to basic interaction data, without deeper analysis of student behavior or consideration of the content quality or time spent on specific activities. This narrow feature set restricted the models’ ability to fully capture the complexity of student engagement. Additionally, while SMOTE was applied to address the class imbalance, the models faced challenges in generalizing well to unseen data, as overfitting was observed in some cases. This suggests that the models occasionally learned patterns specific to the training data, limiting their predictive performance on new, unseen datasets.

Although a Bayesian search was conducted to optimize hyperparameters and manage class imbalance, both models still relied on relatively basic tuning and could benefit from further hyperparameter optimization. More advanced techniques and further optimization could improve the ability to capture the complexities of the data. We opted to use NSGA-II to efficiently explore the trade-offs between multiple conflicting objectives. Future improvements could also expand the feature set to include more sophisticated metrics, such as detailed behavioral patterns and content-specific interactions, enhancing the accuracy and generalizability of the models for identifying at-risk students.

Proposed model

A new approach was developed to overcome the limitations of the existing model. It explored different architectures and ultimately selected the CatBoost algorithm following NSGA-II optimization. The new approach employed hyperparameter optimization using NSGA-II, enabling a comprehensive parameter space exploration. This optimization process included feature selection, hyperparameter tuning, and the choice of resampling strategy (algorithm selection and configuration).

Initially, the model was trained using data from courses with a fixed duration of 15 weeks, as in the original approach. However, the course duration was normalized in a subsequent phase to account for varying lengths. The model’s performance was compared in both fixed 15-week and normalized course duration scenarios.

Key improvements included:

-

Feature selection: The new model incorporated additional features, such as relative course progress, and provided a more granular analysis of weekly engagement metrics, including the type of component log.

-

Hyperparameter optimization: NSGA-II was employed to optimize the models. The CatBoost model included tuning parameters such as the seed, learning rate, tree depth, and the number of trees, resulting in a more fine-tuned model.

-

Class imbalance handling: Various resampling strategies were tested, with ADASYN ultimately selected to oversample the minority class (dropout students). This approach mitigated the dataset’s class imbalance by addressing the underrepresentation of dropout students.

The effectiveness of the NSGA-II search in optimizing the model’s performance across multiple objectives is visualized in the 3D Pareto front shown in Fig. 4. The chart displays accuracy, macro F1-score, and the F1-score for the reprobate class (students who failed the course), which were the objectives of the genetic algorithm search. The Pareto front illustrates how the optimization process converged over generations, aiming to maximize all three metrics simultaneously. Multiple runs were performed with different generations and population size configurations, balancing performance with computational cost. For the final and best-performing model, we achieved optimal results using mutation, crossover, and swapping probabilities of 10%, 70%, and 40%, respectively.

Performance metrics

The performance of the existing model and the proposed model-both the fixed 15-week version and the more flexible model using relative week (current/total) and total weeks as features-was compared using key metrics such as accuracy, F1-score, precision, recall, and AUC-ROC. Tables 5 and 6 summarize the performance of the models. Even the flexible model was evaluated with a 15-week duration in the holdout tests, as shown in the tables, allowing for a direct comparison with the previous models.

Model performance comparison

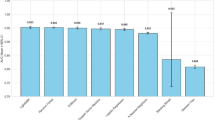

This section compares the performance of two model methodologies: Unique and Multiple. The comparison is based on key performance metrics such as F1-score for approved and failed students and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) score. Figures 5, 6, and 7 summarize the results across multiple weeks.

F1-score for approved students

Figure 5 illustrates the F1-score performance for predicting students who completed the course (approved). The Unique model consistently outperforms the Multiple model across all weeks. From Week 1, the Unique model shows a steady increase in F1-score, reaching approximately 0.98 by Week 13 and maintaining a high level of performance through Week 15. In contrast, the Multiple model demonstrates more variability, peaking at around 0.94 in Week 15 but showing noticeable dips in Weeks 5 and 11. These results suggest that the Unique model offers superior stability and higher accuracy in predicting approved students over time.

F1-score for failed students

Figure 6 presents the F1-score for students who failed the course. The Unique model significantly outperforms the Multiple model, particularly from Week 5 onwards. The F1-score for the Unique model increases from 0.51 in Week 1 to around 0.95 by Week 13, maintaining strong performance through Week 15. In comparison, the Multiple model struggles with lower scores, especially noticeable dips around Weeks 5, 7, and 11, where the F1-score drops to as low as 0.54. This suggests that the Unique model is more effective at identifying at-risk students, offering consistent and reliable predictions across different weeks.

AUC score comparison

The AUC score, shown in Fig. 7, reinforces the superior performance of the Unique model. After Week 3, the AUC of the Unique model consistently exceeds 0.90, peaking at nearly 1.00 by Week 9 and maintaining this level through the remaining weeks. On the other hand, the Multiple model shows more fluctuation, with AUC values dropping around Weeks 7 and 11. The Unique model’s stable AUC scores indicate its ability to generalize effectively across different weeks, offering more reliable predictions for both approved and at-risk students.

Feature importance

To help understand the model’s decision-making process, we employed SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to interpret the feature contributions to the predictions. Figure 8 shows the SHAP summary plot for the final model, highlighting how each feature influences the prediction of student dropout or success.

The SHAP plot reveals that features such as total_weeks (total duration of the course in weeks), days_with_logs_avg (the average number of days a student has activity logs up to the current week), and max_consecutive_days_without_access (the maximum number of consecutive days a student did not access the course platform) had the most significant impact on the model’s predictions of dropouts and students who failed. Specifically, students with fewer weeks of engagement or extended periods without accessing the platform were more likely to be classified as at-risk. Additionally, the results suggest that students in longer courses (with a higher total week count) are more prone to dropping out or failing.

Discussion

The comparison between the old models (Random Forest and XGBoost) and the new model (CatBoost with NSGA-II optimization) demonstrates clear improvements in the performance of the proposed approach, particularly in terms of recall, F1-score, accuracy, and AUC.

F1-Score: As seen in Tables 5 and 6, the proposed model consistently achieved higher F1-scores compared to the old models, particularly in detecting students at risk (reproved class). For instance, in Experiment 1, in Week 5, the F1-score for the reproved class increased from 0.25 (old model) to 0.40 (new model), while in Experiment 2, the F1-score improved from 0.55 (multiple models) to 0.74 (unique model). These results highlight the new model’s significantly improved ability to identify students at risk of failure.

Recall: The new model exhibited higher recall scores across most weeks for the reproved class, demonstrating its ability to identify a greater proportion of at-risk students. For instance, in Experiment 1, in Week 7, the recall for the reproved class decreased from 0.27 (old model) to 0.18 (new model). However, in Experiment 2, the recall improved from 0.82 (multiple models) to 0.85 (unique model). This demonstrates a significant improvement in the new model’s ability to identify at-risk students in Experiment2, making it particularly effective for early interventions.

Accuracy: As with the recall, accuracy showed notable improvements in Experiment2. In Experiment 1, for Week 9, the accuracy for the reproved class decreased slightly from 0.59 (old model) to 0.57 (new model). However, in Experiment 2, the accuracy was higher, rising from 0.85 (multiple models) to 0.95 (unique model). This indicates that the model in Experiment2 performed much better at correctly identifying both reproved and approved students, highlighting its improved predictive capabilities.

AUC: The AUC also demonstrated marked improvements, indicating the model’s enhanced ability to distinguish between at-risk and non-at-risk students. In Experiment 1, for Week 9, the AUC decreased slightly from 0.61 (old model) to 0.56 (new model). However, in Experiment 2, the AUC improved significantly, rising from 0.90 (multiple models) to 1.00 (unique model). This shows that the model in Experiment2 has a much stronger discriminatory ability in identifying at-risk students, further enhancing its practical application for early interventions.

The proposed model, which incorporates course duration as a feature and robust optimization techniques, demonstrated substantial improvements over previous models. The earlier models were limited by relying on cumulative data only up to a given week, whereas the new model leverages NSGA-II hyperparameter optimization and integrates more granular features, including course duration and progression. This enables the model to utilize data from all available weeks more effectively. As a result, the new model offers enhanced generalization across different time frames, improved flexibility, scalability, and significantly more accurate predictions of students’ outcomes.

These results are particularly important in educational data mining, as early detection of students at risk of failure can enable timely interventions, ultimately helping to reduce dropout rates and improve overall student success.

Comparison of metrics with existing studies

In this section, we compare the performance of our model in both experiments with the metrics reported in prior studies. Table 7 summarizes performance metrics from the related work and our experiments, including accuracy, recall, F1-score, and AUC. This comparison emphasizes that our study focused on the F1-score and recall for reproved students, while the studies compared may not have specifically provided metrics for this category.

Several key observations can be drawn from this comparison:

-

Accuracy: The accuracy achieved in our Experiment2 model was 0.90, which is competitive, surpassing21 (0.83) and aligning closely with28 (0.85), while approaching27 (0.955).

-

Recall: Recall in Experiment2 0.85, marks improvement over Experiment1 (0.82) for reproved students. This positions our model’s recall ahead of27 (0.81) and15 (0.72), and approaching28 (0.80) and24 (0.96).

-

F1-Score: The F1-score of 0.86 in Experiment2 for reproved students shows a substantial improvement from Experiment1 (0.79). Our F1-score surpasses27 (0.84) and approaches21 (0.88), while remaining behind24 (0.97). As different studies focus on varying student categories, these discrepancies highlight potential differences in how the metrics were calculated across studies.

-

AUC: The AUC in Experiment2 0.95, represents a significant leap from Experiment1 (0.90). This AUC aligns well with14 (0.90),15 (0.86), and10 (0.91), confirming the model’s strong discriminatory power in differentiating between at-risk and non-at-risk students. Additionally, our model performs competitively with28 (0.87), reinforcing its reliability.

Apart from the performance metrics, comparing the algorithmic approaches and strategies employed by our model and existing studies is essential. Previous studies have utilized models like Random Forest and XGBoost, known for their robustness, but these models lacked the sophisticated hyperparameter optimization employed in our study13. By integrating the NSGA-II, our model demonstrated higher accuracy, recall, and F1-scores, particularly for the minority class of at-risk students. This emphasizes the utility of NSGA-II in fine-tuning model parameters to achieve better predictive performance across various metrics.

For instance, while prior models showed improvements using oversampling techniques such as SMOTE, we applied ADASYN to target the minority class more effectively. This led to significant gains in detecting students at risk of dropout. ADASYN allowed for more targeted sampling of the minority class, providing a better balance and improving the model’s ability to generalize across imbalanced datasets.

Our model introduces dynamic, time-based features-such as relative course duration and week-based engagement metrics-that significantly improve generalizability across various course lengths. Prior studies have demonstrated the importance of LMS interaction logs as predictors of academic outcomes26. However, our model expands on this approach by incorporating course duration as a dynamic feature, adjusting predictions based on student progress through the course. This ability to handle varying course lengths and student behaviors enhances our model’s robustness and sets it apart from the existing literature.

Furthermore, our model offers greater adaptability across different types of courses. While earlier research often focused on specific disciplines or course types, such as STEM subjects, we demonstrated that our model generalizes effectively across a broader range of disciplines. For instance, socioeconomic data has been incorporated to predict dropout rates across educational contexts15. In contrast, our study showed that the model could be generalized across different course types, making it applicable in various educational settings. This flexibility highlights the practical application of our model in diverse institutional contexts, expanding its potential for addressing educational challenges across different fields.

Research questions

Based on the results from our experiments, supported by statistical and distance evaluations, we provide the following answers to the research questions:

Question 1: How effectively can machine learning models, trained on limited student log data from Moodle, generalize to predict outcomes in larger and diverse datasets with unseen courses? Answer. In Experiment1, the models showed moderate generalizability, on week 7 achieving an accuracy of 0.87, but lower recall (0.82) and F1-score (0.79) for at-risk students. This indicates that the models struggled to identify at-risk students effectively in unseen datasets without additional adjustments. Statistical tests (KS statistic of 0.069, p-value close to zero; Mann-Whitney U p-value \(6.33 \times 10^{-49}\)) confirmed significant differences between training and test distributions, suggesting that the data’s homogeneity limits the model’s generalization. This experiment highlights the importance of data quality, especially when working with a limited dataset. A small dataset may not be sufficient for robust generalization in educational contexts, where student behaviors and course designs can vary significantly.

Question 2: Which features in the student log data are most predictive of success or engagement, and do these features remain equally important across different courses? Answer. SHAP analysis and feature selection through NSGA-II highlighted key predictive features:

-

total_weeks: Longer courses correlate with higher dropout likelihood.

-

days_with_logs_avg and max_consecutive_days_without_access: Regular engagement and minimal extended absences are linked to student success.

-

first_log_days_diff and relative_week: Early and consistent engagement benefit outcomes.

Consistent feature selection across models indicates the robustness of these metrics, although relative importance may vary by course structure.

Question 3: Can the NSGA-II multi-objective optimization algorithm effectively enhance machine learning models’ predictive accuracy and reliability for identifying at-risk students in dropout prediction scenarios? Answer. Our implementation of the NSGA-II algorithm produced good results, particularly for the at-risk class, achieving an F1-score of 0.86 on week 7. This genetic algorithm’s flexibility enabled efficient exploration and exploitation of the search space, allowing for simultaneous optimization across multiple areas, such as model selection, feature selection, and hyperparameter tuning. Its multi-objective capability allowed us to optimize for both macro F1-score and recall for failed students, balancing the performance for at-risk students with overall model accuracy. The 3D Pareto front in Fig. 4 illustrates how NSGA-II converged on optimal configurations across metrics, enhancing both recall and stability.

Question 4: How does the predictive accuracy and stability of a single model trained on data from all weeks compare to that of separate models trained on each week? Answer. The performance metrics from Experiment2 reveal that a single model trained on data from all weeks outperformed the individual weekly models. Notably, the single model achieved higher scores in key metrics, including on week 7 an F1-score of 0.86, recall of 0.85, and an AUC of 0.95. These results suggest that the single model that has all the data available provides more accurate predictions than a model that only has the week’s data.

Implications for Predictive Modeling in Education: The results indicate that incorporating cumulative engagement features, optimizing key metrics through NSGA-II, and using week-based features improve model generalizability, stability, and predictive accuracy across diverse educational contexts.

Final remarks

Through two experiments, we evaluated the effects of advanced model architectures and balancing techniques on the accuracy, recall, and reliability of predictions in identifying at-risk students. Experiment 1 provided a baseline using a traditional model tested on holdout data that had not been used in training, addressing the challenge of generalizing machine learning models trained on limited LMS data (Question 1). However, statistical evaluations revealed significant discrepancies between training and test distributions, limiting the model’s generalization to new courses. Experiment 2, in contrast, introduced week-based features and a single model trained on data from all weeks, improving generalization across datasets. The results showed that incorporating week-based features allowed the model to adapt more effectively to different course structures, enhancing its predictive power when applied to unseen data.

The findings also highlight the importance of key predictive features in student log data, answering Question 2. Feature selection through NSGA-II and SHAP analysis consistently identified course duration, total logs, days with access, and inactivity patterns as the most influential factors in dropout prediction. These engagement metrics remained relevant across different contexts, confirming their significance in identifying at-risk students. Furthermore, NSGA-II proved to be an effective optimization approach, improving model performance by balancing recall and F1-scores, which directly addressed Question 3. By optimizing feature selection, hyperparameters, and model architecture, NSGA-II enhanced the predictive accuracy and reliability of the models, particularly in identifying at-risk students. Additionally, the comparative results between Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 answered Question 4, showing that a single model trained on all weeks’ data outperformed separate weekly models. The unified model achieved higher F1-scores, recall, and AUC values over multiple weeks, demonstrating that incorporating cumulative engagement features leads to a more scalable and accurate approach for dropout prediction.

Future work could expand on this research by investigating the performance of the proposed model on larger, more diverse datasets to further validate its robustness. Additionally, exploring the explainability of the model would provide deeper insights into its decision-making process, making it more transparent and actionable for educators. Another important direction is to evaluate the model’s behavior across different academic disciplines, such as STEM, social sciences, and communication studies, to determine whether specialized models yield better predictive accuracy in specific fields. By addressing these aspects, this study contributes to a more scalable and effective approach to student dropout prediction in online learning environments.

Data availability

The manuscript’s raw data are not openly available. Anonymized and preprocessed data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and institutional approval.

References

Jenkins, T. On the difficulty of learning to program, in Proceedings of the 3rd Annual Conference of the LTSN Centre for Information and Computer Sciences, Vol. 4, 53–58 (Citeseer, 2002).

Dunican, E. Making the analogy: Alternative delivery techniques for first year programming courses, in Proceedings of the 14th Annual Workshop of the Psychology of Programming Interest Group, Vol. 2002, 89–99 (2002).

Vihavainen, A., Paksula, M. & Luukkainen, M. Extreme apprenticeship method in teaching programming for beginners, in Proceedings of the 42nd ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, SIGCSE ’11 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1145/1953163.1953196 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2011).

Bennedsen, J. & Caspersen, M. E. Failure rates in introductory programming. SIGCSE Bull. 39, 32–36. https://doi.org/10.1145/1272848.1272879 (2007).

Watson, C. & Li, F. W. Failure rates in introductory programming revisited, in Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Innovation & Technology in Computer Science Education - ITiCSE ’14, 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1145/2591708.2591749 (ACM Press, 2014).

Shynarbek, N., Saparzhanov, Y., Saduakassova, A., Orynbassar, A. & Sagyndyk, N. Forecasting dropout in university based on students’ background profile data through automated machine learning approach, in 2022 IEEE International Conference on Smart Information Systems and Technologies (SIST), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/SIST54437.2022.9945715 (IEEE, 2022).

Cheah, C. S. Factors contributing to the difficulties in teaching and learning of computer programming: A literature review. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 12, ep272. https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/8247 (2020).

Gupta, U. & Zheng, R. Z. Cognitive load in solving mathematics problems: Validating the role of motivation and the interaction among prior knowledge, worked examples, and task difficulty. Eur. J. STEM Educ. 5, 05. https://doi.org/10.20897/ejsteme/9252 (2020).

Shohag, S. & Bakaul, M. A machine learning approach to detect student dropout at university. Int. J. Adv. Trends Comput. Sci. Eng. 10, 3101–3107. https://doi.org/10.30534/ijatcse/2021/041062021 (2021).

Queiroga, E. M. et al. A learning analytics approach to identify students at risk of dropout: A case study with a technical distance education course. Appl. Sci. 10, 3998. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10113998 (2020).

Kuh, G. et al. Using Evidence of Student Learning to Improve Higher Education (Jossey-Bass, 2014).

Aguiar, E., Chawla, N. V., Brockman, J., Ambrose, G. A. & Goodrich, V. Engagement vs performance: Using electronic portfolios to predict student outcomes. J. Learn. Anal. 5, 93–108. https://doi.org/10.18608/jla.2014.13.3 (2018).

Jain, A. & Solanki, S. An efficient approach for multiclass student performance prediction based upon machine learning, in 2019 International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), 1457–1462. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCES45898.2019.9002038 (2019).

Macarini, L. A. B., Cechinel, C., Machado, M. F. B., Ramos, V. F. C. & Munoz, R. Predicting students success in blended learning-evaluating different interactions inside learning management systems. Appl. Sci. 9, 5523. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9245523 (2019).

Krüger, J., Britto, A. & Barddal, J. An explainable machine learning approach for student dropout prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120933 (2023).

Cechinel, C. et al. Workshops. CCIS 2150, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-64315-6_10 (2024).

Sulak, S. A. & Koklub, N. Predicting student dropout using machine learning algorithms. Intell. Methods Eng. Sci. 3, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.58190/imiens.2024.103 (2024).

Sarker, I. H. Machine learning: Algorithms, real-world applications and research directions. SN Comput. Sci. 2, 160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-021-00592-x (2021).

Ndunagu, J. N. et al. Deep learning for predicting attrition rate in open and distance learning (odl) institutions. Computers https://doi.org/10.3390/computers13090229 (2024).

Tamada, M. M., Giusti, R. & de Magalhães Netto, J. F. Predicting students at risk of dropout in technical course using LMS logs. Electronics 11, 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11030468 (2022).

Su, Y.-S., Lin, Y.-D. & Liu, T.-Q. Applying machine learning technologies to explore students’ learning features and performance prediction. Front. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.1018005 (2022).

Nagy, M. & Molontay, R. Interpretable dropout prediction: Towards XAI-based personalized intervention. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 34, 274–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-023-00331-8 (2024).

Oqaidi, K., Aouhassi, S. & Mansouri, K. Towards a students’ dropout prediction model in higher education institutions using machine learning algorithms. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. (iJET) 17, 109–125. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v17i18.25567 (2022).

Dewi, M. A., Kumiadi, F. I., Murad, D. F. & Rabiha, S. G. Machine learning algorithms for early predicting dropout student online learning, in 2023 9th International Conference on Computing, Engineering, and Design (ICCED) 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCED60214.2023.10425359 (IEEE, 2023).

Poellhuber, L.-V., Poellhuber, B., Desmarais, M., Léger, C. & Vu, M. M.-C. Cluster-based performance of student dropout prediction as a solution for large scale models in a moodle LMS, in Proceedings of the 13th International Learning Analytics and Knowledge Conference (LAK 2023) 592–598, https://doi.org/10.1145/3576050.3576146 (ACM, 2023).

Wang, Q. & Mousavi, A. Which log variables significantly predict academic achievement? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Educ. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13282 (2022).

Cho, C.-H., Yu, Y. W. & Kim, H. G. A study on dropout prediction for university students using machine learning. Appl. Sci. 13, 12004. https://doi.org/10.3390/app132112004 (2023).

Kok, C. L., Ho, C. K., Chen, L., Koh, Y. Y. & Tian, B. A novel predictive modeling for student attrition utilizing machine learning and sustainable big data analytics. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14219633 (2024).

Deb, K., Pratap, A., Agarwal, S. & Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 6, 182–197. https://doi.org/10.1109/4235.996017 (2002).

James, G. M., Witten, D., Hastie, T. J. & Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R. Springer Texts in Statistics (Springer, New York, 2013). corrected at 6th printing 2015 edn.

Dorogush, A. V., Ershov, V. & Gulin, A. Catboost: Gradient boosting with categorical features support. ArXiv arXiv:1810.11363 (2018).

He, H., Bai, Y., Garcia, E. A. & Li, S. Adasyn: Adaptive synthetic sampling approach for imbalanced learning, in IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks 1322–1328, https://doi.org/10.1109/IJCNN.2008.4633969 (2008).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2012).

Verma, S., Pant, M. & Snasel, V. A comprehensive review on NSGA-II for multi-objective combinatorial optimization problems. IEEE Access 9, 57757–57791. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3070634 (2021).

Yusoff, Y., Ngadiman, M. & Zain, A. Overview OF NSGA-II for optimizing machining process parameters. Procedia Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2011.08.745 (2011).

Nguyen, C. D., Carlin, J. B. & Lee, K. J. Diagnosing problems with imputation models using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test: A simulation study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13, 144. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-144 (2013).

Nachar, N. The Mann-Whitney u: A test for assessing whether two independent samples come from the same distribution. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 4, 13–20. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.04.1.p013 (2008).

Funding

This work was funded by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq)—grant 409633/2022-4

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: Jointly responsible by Markson Marcolino and Thiago Porto. Data collection: Primarily completed by Cristian Cechinel and Rafael Targino. Data analysis and interpretation: Conducted jointly by Thiago Porto and Markson Marcolino. Manuscript writing: The first draft was completed by Markson Marcolino, with subsequent revisions handled by Thiago Porto, Emanuel Marques Queiroga and Cristian Cechinel. Final review: Conducted by Roberto Munoz, Rafael Targino, Cristian Cechinel, Emanuel Marques Queiroga and Tiago Thompsen Primo. Funding and Material Acquisition: Cristian Cechinel, Vinícius Faria Culmant Ramos, Emanuel Marques Queiroga and Tiago Thompsen Primo. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rebelo Marcolino, M., Reis Porto, T., Thompsen Primo, T. et al. Student dropout prediction through machine learning optimization: insights from moodle log data. Sci Rep 15, 9840 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93918-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93918-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Explainable artificial intelligence for predicting medical students’ performance in comprehensive assessments

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Enhancing Student Dropout Prediction in MOOCs Using Graph Neural Networks and Link Augmentation

SN Computer Science (2025)