Abstract

A thorough and current analysis of the burden and evolving trends in depressive disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic from 2019 to 2021 remains unavailable. Employing the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 database, we evaluated the burden of depressive disorders at the global, regional, and national levels, stratifying the analysis by age, gender, and socio-demographic index (SDI). To examine trends in depressive disorders during the epidemic, we calculated the estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) in age-standardized incidence rates (ASIR), age-standardized prevalence rates (ASPR), and age-standardized DALYs rates (ASDR) across all levels from 2019 to 2021. Furthermore, we performed a frontier analysis of depressive disorders across various countries, incorporating risk factor analyses at multiple levels. In 2021, the global incidence of depressive disorders stood at 357.43 million, while the prevalence was recorded at 332.41 million, accompanied by 56.33 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a notable upward trend in ASIR (EAPC = 8.33 [-0.46 to 17.9]), ASPR (EAPC = 6.02 [0.28 to 12.09]), and ASDR (EAPC = 7.13 [-0.18 to 14.97]) for depressive disorders on a global scale. The burden of depressive disorders is most pronounced among females and individuals aged 60 to 64 within their respective subgroups. From 1990 to 2021, the burden of depressive disorders consistently remained highest in the low SDI region; however, it experienced the most significant increase in the high SDI region during the COVID-19 pandemic from 2019 to 2021. In 2021, the burden of depressive disorders was highest in central sub-Saharan Africa, Greenland, and Uganda, while the Andean region of Latin America, along with Bulgaria and Belarus, experienced the most significant increase in depressive disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Globally, bullying victimization, intimate partner violence, and childhood sexual abuse contributed to 6.47%, 4.91%, and 2.65% of the ASDR for depressive disorders, respectively. The global burden of depressive disorders has markedly increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, gradually shifting from low to high SDI regions, particularly in North America and Europe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a pervasive mental disorder, depressive disorders are marked by symptoms such as a diminished ability to experience pleasure, an intensification of depressive symptoms at particular times during waking hours, and an increased sense of guilt related to the illness itself1. In the United States, the lifetime prevalence of moderate-to-severe depressive disorders among adolescents aged 13–18 years was 11.0%, with a one-year prevalence of 7.5%2. In 2014, there were over 300 million cases of depressive disorders worldwide, which the World Health Organization (WHO) recognized as the leading single contributor to global disability3. Additionally, women are nearly twice as likely as men to experience depressive disorders, a disparity that is closely linked to biological and psychological vulnerabilities, as well as environmental influences4,5. A global systematic review examined the economic burden of depressive disorders, estimating that the annual direct costs per case range from $1,000 to $2,500, morbidity-related costs from $2,000 to $3,700, and mortality-related costs from $200 to $4006. Although developing and implementing effective interventions for depressive disorders is strategically vital in alleviating the burden of depressive disorders, geographic and demographic variations introduce complexities that complicate the decision-making process. Consequently, the collection of current data on global patterns and trends in the spatial and temporal distribution of depressive disorders has become essential.

The latest highly rated Lancet article reports that, during the 2020 period of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were an additional 53.2 million cases of major depressive disorders globally, resulting in 49.4 million major depressive disorders-associated DALYs7. This provides a valuable reference for addressing the gaps in understanding the trends of major depressive disorders during the pandemic. However, the article primarily concentrates on the early to mid-pandemic period and does not explore the later stages of the 2021 pandemic. Furthermore, the study focuses exclusively on major depressive disorders, excluding mild to moderate depressive disorders from its scope. Therefore, a thorough evaluation of all depressive disorders throughout the entire course of the COVID-19 pandemic would provide a more accurate understanding of its near-term impact on the mental health of the population8,9.

The latest GBD 2021 study offers extensive data on 371 diseases and injuries, along with 88 major risk factors, covering 54 regions and 204 countries globally from 1990 to 202110. By utilizing the GBD 2021 database, this study seeks to analyze the global burden and trends of depressive disorders from 2019 to 2021; to stratify the global trends by age, gender, socio-demographic index (SDI), country, and regional levels; to examine the impact of risk factors on the burden of depressive disorders.

Methods

Data details

All raw data were sourced from the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) query tool (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/), encompassing annual data on the incidence, prevalence, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) of depressive disorders across various strata from 1990 to 2021, along with the corresponding age-standardized rates (ASRs)10. All raw data are compiled in Supplementary Table 1. Additionally, the GBD 2021 study employed the Bayesian meta-regression tool, DisMod-MR 2.1, as the principal methodology, ensuring consistency in the incidence, prevalence, and DALYs across all diseases11,12.

Disease definition

In the 2021 GBD database, depressive disorders are classified in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision (ICD-10) into two categories: major depressive disorder (MDD) and dysthymia. As a form of recurrent depressive disorder, MDD can manifest throughout an individual’s lifespan, with the intensity of each episode differing. As a chronic and milder form of persistent depressive disorder, dysthymia, while presenting with less severe symptoms than MDD, follows a protracted course. Cases of MDD and dysthymia that meet the diagnostic criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) and ICD are incorporated into the GBD 2021 database13.

Details of the indicators

As the most comprehensive and illustrative measure for evaluating the overall impact of disease, DALY represents the sum of years of life lost (YLL) and years lived with disability (YLD)10. To account for variations in age composition, ASR was calculated using the standard population age structure as updated by the National Standard Data 2021 and is reported per 100,000 population. The calculation method is elaborated upon in detail in prior literature13. The SDI is a composite measure of a countries or region’s development, combining data on per capita educational attainment, per capita income, and the total fertility rate among young females. Based on the SDI index, the GBD 2021 database classifies the world into five categories: low (0-0.45), low-middle (0.45–0.61), middle (0.61–0.69), high-middle (0.69–0.81), and high SDI (0.81-1)14. The 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs) were calculated using a stochastic Markov chain Monte Carlo model10.

Estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) analyses

Figures 1 and 2 reveal a marked upward trend in all ASRs for depressive disorders between 2019 and 2021. To more accurately assess the changes in the burden of depressive disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic period from 2019 to 2021, we calculated EAPCs for all ASRs. The EAPCs were calculated using a linear regression model: y = α + βx + ε, where x represents the calendar year, y represents the logarithm of the ASRs, ε denotes the error term, and β reflects the positive or negative trend in the ASRs15. Based on the assumption that the natural logarithm of ASRs follows a linear trend over time, the equation for EAPC can be derived as EAPC = 100 × [exp(β) -1]. The 95% confidence interval (CI) is similarly derived from the linear regression model, reflecting the range of uncertainty around EAPCs. If both EAPC and the lower bound of the 95% CI are greater than 0, this signifies an increase in the ASR. Conversely, a decrease in the ASR was indicated if both the EAPC value and the upper bound of the 95% CI were less than 016.

Frontier analyses

Frontier analysis assesses the unrealized health potential of each country or region relative to its level of development by establishing an optimal “frontier” or boundary. This frontier defines the minimum age-standardized burden of disease achievable at different levels of the SDI. The effective difference for each country or region is then calculated based on its SDI and corresponding ASRs, allowing for the measurement of the gap between actual and achievable health outcomes17.

Risk factor analyses

In the GBD 2021 database, depressive disorders are associated with three key risk factors: intimate partner violence, bullying victimization, and childhood sexual abuse10. The proportional attributable score is calculated to estimate the reduction in the incidence of depressive disorders that would occur if exposure to a given risk factor were reduced to the theoretical minimum level of risk.

All analyses and visualizations in this study were conducted using R software, version 4.3.2, in conjunction with Microsoft Office Home and Student Edition 2021.

Results

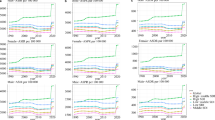

As depicted in Figs. 1 and 2, the age-standardized incidence rates (ASIR), age-standardized prevalence rates (ASPR), and age-standardized DALYs rates (ASDR) for depressive disorders remained relatively stable globally between 1990 and 2005, across gender, SDI groups, and various age cohorts. A slight downward trend in ASRs for depressive disorders was observed between 2005 and 2010. However, between 2019 and 2021, depressive disorders experienced significant increases across all subgroups. Therefore, this study aims to assess the burden and trends of depressive disorders from 2019 to 2021 by utilizing various cross-sectional datasets.

Global trends

As illustrated in Table 1, the global ASIR for depressive disorders increased significantly between 2019 and 2021 (from 3692.5 [95% UI: 3224.73-4328.39] per 100,000 population in 2019 to 4333.62 [3770.8-5093.61] per 100,000 population in 2021; EAPC = 8.33 [95% CI: -0.46 to 17.9]). Consequently, the ASPR for depressive disorders also saw a significant increase (from 3564.77 [3211.82-4002.9] per 100,000 population in 2019 to 4006.82 [3581.26-4539.01] per 100,000 population in 2021; EAPC = 6.02 [0.28–12.09]). Similarly, there was a significant rise in the ASDR for depressive disorders from 2019 to 2021 (from 593.5 [413.34-810.07] per 100,000 population in 2019 to 681.14 [475.19-923.83] per 100,000 population in 2021; EAPC = 7.13 [-0.18 to 14.97]). Within two years, the global incidence (357,438,730 cases in 2021), prevalence (332,410,333 cases in 2021), and DALYs (56,330,361 in 2021) for depressive disorders increased by an average of 1.17 times. The incidence, prevalence, and DALYs of depressive disorders from 1990 to 2021, along with the corresponding ASRs, are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Global trends by sex

Between 2019 and 2021, there was a significant global increase in the ASIR for depressive disorders in both males and females, with an EAPC of 8.13 for males (95% CI: 0.15–16.75; from 2879.04 [95% UI: 2504.78-3368.55] per 100,000 population in 2019 to 3366.27 [2922.76-3958.07] per 100,000 population in 2021) and 8.51 for females (95% CI: -0.81 to 18.72; from 4496.81 [3937.5-5277.23] per 100,000 population in 2019 to 5295.22 [4606.32-6227.48] per 100,000 population in 2021). Similarly, the ASPR for depressive disorders saw a significant increase in both males (EAPC = 5.76 [0.7-11.07]) and females (EAPC = 6.23 [0.02–12.82]). As illustrated in Table 1, the ASDR due to depressive disorders also increased substantially between 2019 and 2021 for both males (from 472.64 [329.54-648.13] per 100,000 population in 2019 to 540.51 [377.31-735.48] per 100,000 population in 2021; EAPC = 6.94 [0.36–13.95]) and females (from 713.3 [497.52-969.56] per 100,000 population in 2019 to 821.17 [570.96-1110.43] per 100,000 population in 2021; EAPC = 7.3 [-0.5 to 15.71]) globally. Figure 1 demonstrates that the burden of depressive disorders has consistently been approximately 1.5 times higher for females than for males from 1990 to 2021, with a significantly greater growth rate observed from 2019 to 2021.

Global trends by age group

The largest increases in the global burden of depressive disorders between 2019 and 2021 were observed among young children aged < 5 years (EAPC of ASIR: 14.14 [95% CI: -0.77 to 31.28]; EAPC of ASPR: 11.65 [-0.7 to 25.54]; EAPC of ASPR: 13.41 [-0.64 to 29.46]). Overall, the rise in the burden of depressive disorders during this period diminished with increasing age. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the highest values of ASIR (6474.64 [95% UI: 5039.91-8302.76] per 100,000 population), ASPR (6454.47 [5302.8-7765.12] per 100,000 population), and ASDR (1038.97 [700.87-1439.52] per 100,000 population) for depressive disorders in 2021 were observed in individuals aged 60–64 years. However, the burden of depressive disorders in the cohort aged over 80 years demonstrates a slow but steady decline from 1990 to 2021.

Global trends by SDI

As indicated in Table 1, between 2019 and 2021, the ASIR for depressive disorders experienced the most pronounced increase in the high SDI quintile, with an EAPC of 11.76 (95% CI: -0.65 to 25.72; from 4004.34 [95% UI: 3545.99-4632.28] per 100,000 population in 2019 to 5001.7 [4364.28-5837.96] per 100,000 population in 2021), followed by low-middle SDI quintile (EAPC = 8.46 [-0.88 to 18.7]), middle SDI quintile (EAPC = 7.99 [-0.7 to 17.44]), high-middle SDI quintile (EAPC = 6.93 [0.68–13.56]), and low SDI quintile (EAPC = 5.64 [-0.48 to 12.13]). Following a similar pattern, the highest EAPC values for ASPR (EAPC = 8.78 [-0.88 to 18.7]) and ASDR (EAPC = 10.24 [-0.44 to 22.07]) are also observed in the high SDI quintile. In contrast, the highest values of ASIR (5511.85 [4713.36-6539.42] per 100,000 population), ASPR (4849.64 [4260.97-5554.66] per 100,000 population), and ASDR (837.53 [569.85-1140.07] per 100,000 population) for depressive disorders in 2021 were all concentrated within the low SDI quintile. Furthermore, as illustrated in Fig. 2, the low SDI quintile exhibited a significantly higher burden of depressive disorders from 1990 to 2021 compared to the other SDI quintiles.

Regional trends

As shown in Supplementary Table 2, among the 54 GBD regions, the three regions with the largest increases in ASIR for depressive disorders between 2019 and 2021 were Andean Latin America (from 2789.18 [95% UI: 2396.48-3363.63] per 100,000 population in 2019 to 3764.83 [3107-4617.21] per 100,000 population in 2021; EAPC = 16.18 [95% CI: -7.69 to 46.23]), High-income North America (from 5030.22 [4493.69-5723.01] per 100,000 population in 2019 to 6572.24 [5787.27-7626.11] per 100,000 population in 2021; EAPC = 14.3 [-1.53 to 32.68]), and North America (from 5029.59 [4493.13-5722.17] per 100,000 population in 2019 to 6571.38 [5786.46-7625.09] per 100,000 population in 2021; EAPC = 14.3 [-1.53 to 32.68]). Similarly, the top three regions with the highest growth rates in ASPR and ASDR for depressive disorders were likewise Andean Latin America, High-income North America, and North America, in that respective order. However, Central Sub-Saharan Africa was the GBD region with the highest ASIR (7703.41 [6194.22-9565.94] per 100,000 population), ASPR (6337.03 [5236.44-7669.98] per 100,000 population), and ASDR (1136.91 [756.88-1588.38] per 100,000 population) for depressive disorders in 2021.

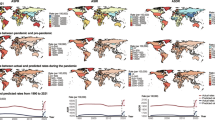

National trends

As depicted in Fig. 3, the countries with the most pronounced increasing trend in ASIR for depressive disorders between 2019 and 2021, in order, are Bulgaria (from 2681.55 [95% UI: 2285.45-3147.6] per 100,000 population in 2019 to 3806.83 [2906.43-4911.38] per 100,000 population in 2021; EAPC = 19.15 [95% CI: 18.36–19.94]), Belarus (from 4469.02 [3827.68-5266.77] per 100,000 population in 2019 to 6256.58 [4727.61-8083.79] per 100,000 population in 2021; EAPC = 18.32 [16.72–19.94]), and North Macedonia (from 2457.87 [2099.63-2867.39] per 100,000 population in 2019 to 3414.83 [2635.75-4393.57] per 100,000 population in 2021; EAPC = 17.87 [7.71–28.99]). Between 2019 and 2021, the two countries with the most significant growth trends in depressive disorders ASPR, as well as the two with the most pronounced increases in ASDR, were Lebanon and Belarus. In 2021, Greenland (ASIR: 9885.55 [7594.04-12631.2] per 100,000 population; ASPR: 7686.01 [6116.13-9616.31] per 100,000 population; ASDR: 1467.92 [964.97-2142.69] per 100,000 population) and Uganda (ASIR: 9644.06 [7284.35-12568.13] per 100,000 population; ASPR: 7769.97 [6262.35-9849.65] per 100,000 population; ASDR: 1419.57 [921.53-2059.49] per 100,000 population) had the highest burden of depressive disorders. Additionally, Fig. 3 reveals that India and China had the highest number of incident cases of depressive disorders in 2021, with 10.78 million (19.82%) and 7.86 million (11.86%) cases of anxiety disorders globally, respectively.

The number of incidences, prevalence, DALYs, ASRs, and EAPC for depressive disorder in 204 countries and regions from 2019 to 2021. (A) ASIR in 2021; (B) ASPR in 2021; (C) ASDR in 2021; (D) incidences in 2021; (E) prevalences in 2021; (F) DALYs in 2021; (G) EAPC for ASIR from 2019 to 2021; (H) EAPC for ASPR from 2019 to 2021; (I) EAPC for ASDR from 2019 to 2021.

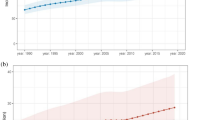

Frontier analysis

As depicted in Fig. 4 and detailed in Supplementary Table 3, frontier analysis reveals that the top five countries with the largest effective differences in ASIR are, in order, Palestine, Lesotho, Angola, Lebanon, and Guyana (range from: 7951.51-6267.88). The top five countries with the largest effective differences in ASPR are, in order, Greenland, Palestine, Greece, Tunisia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (range from: 6042.49-3922.3). Similarly, the top five countries with the largest effective differences in ASDR are Greenland, Palestine, Lesotho, Equatorial Guinea, and Guyana (range from: 1206.01-808.11).

Risk factors

As illustrated in Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 1, three key risk factors – intimate partner violence, bullying victimization, and childhood sexual abuse – accounted for 4.91% [95% IU: 0.02-10.36%], 6.47% [3.14-11.08%], and 2.65% [1.49-4.02%] of global depressive disorders ASDR in 2021, respectively. At the gender level, depressive disorders ASDR in males is primarily influenced by childhood sexual abuse (9.17% [4.55-15.49%]), while in females, it is predominantly affected by intimate partner violence (8.13% [0.03-17.08%]). The ASDR for depressive disorders in young individuals aged 10–25 years is primarily influenced by bullying victimization (range from: 14.20-16.83%), whereas in older adults aged 45–49 years, the ASDR for depressive disorders is mainly driven by intimate partner violence (6.23% [0.02-13.02%]). Bullying victimization had the greatest impact on depressive disorders-related ASDR in high SDI regions (7.99% [4.18-13.25%]), whereas intimate partner violence was the leading factor influencing depressive disorders-related ASDR in low SDI regions (5.81% [0.03-12.34%]). Bullying victimization accounted for 9.49% (5.05-15.70%) of the ASDR for depressive disorders in High-income North America, while intimate partner violence contributed to 7.49% (0.04-15.28%) of the ASDR for depressive disorders in Commonwealth Low Income regions. The countries most affected by bullying victimization (13.34% [6.60-22.55%]), childhood sexual abuse (7.95% [4.63-11.79%]) and intimate partner violence (8.35% [0.04-17.29%]) are, respectively, Qatar, Nigeria and Bangladesh. As the two countries with the highest burden of depressive disorders in 2021, 13.26% (7.13-21.70%) of the ASDR for depressive disorders in Greenland was attributable to bullying victimization, while 8.29% (0.05-16.95%) of the ASDR for depressive disorders in Uganda was attributable to intimate partner violence.

Discussion

Utilizing the 2021 GBD database, this study presents a comprehensive analysis of the burden of depressive disorders across diverse populations, examining global, regional, and national trends, as well as age- and sex-specific patterns, throughout the COVID-19 pandemic from 2019 to 2021, with particular emphasis on EAPC. The annual incidence, prevalence, and DALYs of depressive disorders experienced notable global increases during the COVID-19 pandemic, having reached 357.43 million incident cases, 332.41 million prevalent cases, and 56.33 million DALYs by 2021. As detailed in Supplementary Table 2, the burden of depressive disorders exhibited a pronounced upward trend between 2019 and 2021 across all gender subgroups, GBD subregions, SDI subregions, and the majority of age groups, countries, and regions. Countries such as Palestine, Greenland, and Lesotho possess the highest attainable health potential relative to their respective levels of development. Globally, bullying victimization, intimate partner violence, and childhood sexual abuse contributed to 6.47%, 4.91%, and 2.65% of the ASDR for depressive disorders, respectively.

Among gender subgroups, the burden of depressive disorders is considerably higher for females than for males. This disparity is largely attributable to females being more prone to experiencing adverse events and emotions, such as perinatal and menopausal mood fluctuations, domestic violence, sexual abuse, and discrimination, as well as confronting internalized psychological barriers18,19,20. In female physiology, estrogen plays a crucial role in mood regulation by modulating neurotransmitter turnover and enhancing serotonergic activity21. However, its levels fluctuate markedly across various physiological stages, including puberty, the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause, thereby heightening susceptibility to depressive disorders22,23. This is further corroborated by evidence showing that estrogen therapy significantly alleviates depressive disorders in perimenopausal women24. Furthermore, Anindit discovered that estrogen disruption in menopausal mice induces dysregulation of BDNF-5-HT2A signaling and impairs synaptic plasticity, thereby heightening the brain’s vulnerability to depressive disorders20.

In 2021, the age group with the highest ASIR, ASPR, and ASDR for depressive disorders was the population aged 60–64 years. This population is experiencing a significant shift from an outward focus on external matters to an inward focus on their own bodies, a transition marked by heightened loneliness and declining cognitive function, which contributes to emotional instability13. Additionally, logistic regression analyses revealed that depressive disorders in older adults was significantly associated with factors such as living alone, unemployment, chronic illness, sleep disorders, suicidal ideation, financial stress, and inadequate social support25. However, the greatest increase in the burden of depressive disorders between 2019 and 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, occurred among children aged < 5 years, with the rate of increase in the burden of depressive disorders declining with age during this period. These results should be interpreted with caution, as they are primarily driven by the sharp decline in the total number of children aged < 5 years, which is largely attributable to the global total fertility rate dropping by more than half between 1950 and 202126.

Although the burden of depressive disorders was consistently higher in low SDI regions compared to other SDI regions from 1990 to 2021, the most significant increase during the COVID-19 pandemic occurred in high SDI regions. This suggests a shifting trend, with the burden of depressive disorders increasingly impacting high SDI regions. Low SDI regions are defined by entrenched poverty, economic disparity, limited access to education, structural violence, discrimination, political repression, and social marginalization, among other critical risk factors, all of which contribute to the onset, intensification, and persistence of depressive disorders27,28,29. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, high SDI regions faced stricter lockdown measures, leading to a swift rise in unemployment and increased socio-economic pressures. Additionally, reduced interpersonal contact and disrupted information flow during isolation made individuals more susceptible to feelings of loneliness, which in turn contributed to an increase in depressive disorders9. Nevertheless, study samples in high SDI regions are often derived from highly educated urban populations, who are more likely to acknowledge and seek diagnoses for mental health issues. Furthermore, the ongoing refinement and standardization of diagnostic systems in these areas have led to an increased identification of individuals with potential depressive disorders. From the perspective of the WEIRD paradox, therefore, the rising prevalence of depressive disorders in high SDI countries may not necessarily reflect a genuine worsening of the condition, but rather a more accurate diagnosis and recognition of the disorder30.

In 2021, the regions with the highest burden of depressive disorders were Central Sub-Saharan Africa, as well as countries such as Greenland and Uganda. Between 2019 and 2021, the fastest-growing burden of depressive disorders occurred in Andean Latin America and European countries including Bulgaria and Belarus. As one of the countries with the highest HIV prevalence rates globally, Uganda continues to have a significant number of people infected with and living with the virus, particularly in rural areas, despite a decline in incidence in recent years31. A substantial body of literature now confirms the high prevalence of depressive disorders among individuals living with HIV in Uganda, highlighting their strong association with inadequate social support, food insecurity, and HIV-related neurocognitive disorders32,33. Therefore, strengthening HIV control measures and raising public awareness in Uganda are crucial strategies to mitigate the development of depressive disorders among those affected. As a consequence of the ongoing process of urbanization, the prevalence of occupational stress, income inequality and social stratification is increasing in Greenland34. This is leading to a rise in depressive behaviors, including alcoholism and suicide. Furthermore, the pronounced seasonal variations in light and darkness prevalent in Greenland, which contribute to sleep deprivation, coupled with communication barriers in sparsely populated regions and the extreme cold climate, play a crucial role in the onset of depressive disorders35. Genetically, the distinctive genetic backgrounds, coupled with the shift towards a Westernized diet, have fostered a rapid increase in susceptibility to cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, thereby contributing to the emergence of depressive disorders36,37. Although there is a lack of literature specifically investigating the underlying causes of the dramatic rise in depressive disorders in Bulgaria and Belarus during the COVID-19 pandemic from 2019 to 2021, both countries experienced a volatile political climate during this period, which could have exacerbated depressive disorders and contributed to economic decline38.

Furthermore, frontier analyses reveal that countries like Palestine, Greenland, and Lesotho exhibit the greatest effective differences in reducing the burden of depressive disorders relative to their respective stages of development, indicating the highest levels of unrealized health potential. Palestine has borne the profound consequences of the ongoing conflict, particularly the extensive devastation wrought by the protracted Israeli-Palestinian war; Political unrest and economic turmoil characterized the period in Lesotho during the COVID-19 pandemic39. Consequently, we fervently urge relevant international agencies to provide humanitarian assistance and economic support, both of which are crucial for alleviating depressive disorders.

Among the three risk factors, the burden of depressive disorders associated with bullying victimization was the most severe, exhibiting the highest prevalence among individuals aged 10–24 years and in high-income countries, including North America, Qatar, and Greenland; the burden of depressive disorders stemming from intimate partner violence is primarily concentrated among females aged 45 to 49 years, particularly in low SDI regions, Commonwealth Low-Income areas, and countries such as Uganda and Bangladesh; the burden of depressive disorders resulting from childhood sexual abuse is predominantly observed among men, especially in Western Africa, with Nigeria being notably affected. Thus, it is essential for different countries to customize their policies to enhance effectiveness in mitigating the burden of depressive disorders.

This study contains certain limitations. First, the availability and comprehensiveness of data are constrained by the absence of robust civil registration and vital statistics systems in many low- and middle-income countries, necessitating cautious interpretation of the study’s results. Secondly, the collaborators employed various statistical modeling techniques, which introduced a degree of uncertainty and may have compromised the accuracy of the data. Thirdly, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on depressive disorders varies across regions and countries, such as in Greenland and Uganda40,41. Therefore, incorporating the effects of COVID-19 and national public health strategies as categorical covariates in statistical modeling could facilitate a more nuanced analysis of depressive disorders.

Conclusion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the global burden of depressive disorders demonstrated a notable upward trend. Between 1990 and 2021, the burden of depressive disorders was predominantly concentrated in low SDI regions. However, during the 2019–2021 pandemic, this burden progressively shifted towards high SDI regions, with a notable increase in North America and Europe.

Data availability

Data underlying the results presented in this paper are not publicly available at this time but may be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Malhi, G. S. & Mann, J. J. Depression [J]. Lancet (London, England) 392(10161), 2299–312 (2018).

Avenevoli, S. et al. Major depression in the national comorbidity survey-adolescent supplement: prevalence, correlates, and treatment [J]. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 54(1), 37-44.e2 (2015).

Smith, K. Mental health: a world of depression [J]. Nature 515(7526), 181 (2014).

Kessler, R. C. & Bromet, E. J. The epidemiology of depression across cultures [J]. Annu. Rev. Public Health 34, 119–38 (2013).

Kuehner, C. Why is depression more common among women than among men? [J]. The lancet Psychiatry 4(2), 146–58 (2017).

Luppa, M. et al. Cost-of-illness studies of depression: a systematic review [J]. J. Affect. Disord. 98(1–2), 29–43 (2007).

Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic [J]. Lancet (London, England), 2021, 398(10312): 1700–12.

Hertz-Palmor, N. et al. Association among income loss, financial strain and depressive symptoms during COVID-19: Evidence from two longitudinal studies [J]. J. Affect. Disord. 291, 1–8 (2021).

Lei, L. et al. Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the COVID-19 epidemic in Southwestern China [J]. Med. Sci. Monitor: Int. Med. J. Experimental Clin. Res. 26, e924609 (2020).

Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 [J]. Lancet (London, England), 2024, 403(10440): 2133–61.

Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 [J]. Lancet (London, England), 2020, 396(10258): 1223–49.

Hong, C. et al. Global trends and regional differences in the burden of anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder attributed to bullying victimisation in 204 countries and territories, 1999–2019: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study [J]. Epidemiol. Psychiatric Sci. 31, e85 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Temporal and spatial trend analysis of all-cause depression burden based on Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019 study [J]. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 12346 (2024).

Piao, J. et al. Alarming changes in the global burden of mental disorders in children and adolescents from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study [J]. European child & adolescent psychiatry 31(11), 1827–45 (2022).

Zhang, K. et al. Global, regional, and National epidemiology of diabetes in children from 1990 to 2019 [J]. JAMA Pediatr. 177(8), 837–46 (2023).

Li, D. P. et al. A global assessment of incidence trends of autoimmune diseases from 1990 to 2019 and predicted changes to 2040 [J]. Autoimmun. Rev. 22(10), 103407 (2023).

Pan, H. et al. The global, regional, and national early-onset colorectal cancer burden and trends from 1990 to 2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 [J]. BMC public health 22(1), 1896 (2022).

Abate, K. H. Gender disparity in prevalence of depression among patient population: a systematic review [J]. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 23(3), 283–8 (2013).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature [J]. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 20(4), 359–64 (2007).

Chhibber A., Woody S. K., Karim Rimi M. A., et al. Estrogen receptor β deficiency impairs BDNF-5-HT(2A) signaling in the hippocampus of female brain: A possible mechanism for menopausal depression [J]. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2017, 82: 107–16.

McEwen, B. S. & Alves, S. E. Estrogen actions in the central nervous system [J]. Endocr. Rev. 20(3), 279–307 (1999).

Dagher R. K., Bruckheim H. E., Colpe L. J., et al. Perinatal Depression: Challenges and Opportunities [J]. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 30(2): 154–9 (2021).

Dickerson, L. M., Mazyck, P. J. & Hunter, M. H. Premenstrual syndrome [J]. Am. Family Phys. 67(8), 1743–52 (2003).

Ancelin, M. L., Scali, J. & Ritchie, K. Hormonal therapy and depression: are we overlooking an important therapeutic alternative? [J]. J. Psychosom. Res. 62(4), 473–85 (2007).

Abe, Y. et al. Comparisons of the prevalence of and risk factors for elderly depression between urban and rural populations in Japan [J]. Int. Psychogeriatr. 24(8), 1235–41 (2012).

Global fertility in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2021, with forecasts to 2100: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 [J]. Lancet (London, England), 2024, 403(10440): 2057–99.

Brinda, E. M. et al. Health, Social, and Economic Variables Associated with Depression Among Older People in Low and Middle Income Countries: World Health Organization Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health [J]. Am. J. Geriatric Psychiatry: Official J. Am. Association Geriatric Psychiatry 24(12), 1196–208 (2016).

Pereira, B. et al. The explanatory models of depression in low income countries: listening to women in India [J]. Journal of affective disorders 102(1–3), 209–18 (2007).

Tazi, I., Nafil, H. & Mahmal, L. Depression, palliative care, and hematologic malignancies: the paradox in low-income countries [J]. J. Palliat. Med. 15(3), 260–1 (2012).

Ruiz, J. M., Sbarra, D. & Steffen, P. R. Hispanic ethnicity, stress psychophysiology and paradoxical health outcomes: A review with conceptual considerations and a call for research [J]. Int. J. Psychophysiology: Official J. Int. Organ. Psychophysiol. 131, 24–9 (2018).

Dirlikov, E. et al. Scale-up of HIV antiretroviral therapy and estimation of averted infections and HIV-related deaths - Uganda, 2004–2022 [J]. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report 72(4), 90–4 (2023).

Seffren, V. et al. Association between coping strategies, social support, and depression and anxiety symptoms among rural Ugandan women living with HIV/AIDS [J]. AIDS care 30(7), 888–95 (2018).

Namagga, J. K. et al. Depression and HIV associated neurocognitive disorders among HIV infected adults in rural southwestern Uganda: a cross-sectional quantitative study [J]. BMC psychiatry 21(1), 350 (2021).

Hua, Z., Wang, S. & Yuan, X. Trends in age-standardized incidence rates of depression in adolescents aged 10–24 in 204 countries and regions from 1990 to 2019 [J]. J. Affect. Disord. 350, 831–7 (2024).

Björkstén K S, Bjerregaard P, Kripke D F. Suicides in the midnight sun--a study of seasonality in suicides in West Greenland [J]. Psychiatry research, 2005, 133(2–3): 205–13.

Andersen, M. K. & Hansen, T. Genetics of metabolic traits in Greenlanders: lessons from an isolated population [J]. J. Intern. Med. 284(5), 464–77 (2018).

Hare, D. L. et al. Depression and cardiovascular disease: a clinical review [J]. Eur. Heart J. 35(21), 1365–72 (2014).

Gylfason, T. & Hochreiter, E. To grow or not to grow: Belarus and Lithuania [J]. Comp. Econ. Stud. 65(1), 137–67 (2023).

Abu-Ras, W. et al. Interventions to promote mental health in the Occupied Palestinian Territories and Palestinian refugees: A scoping review [J]. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 70(6), 1037–54 (2024).

Sarki, A. M., Ezeh, A. & Stranges, S. Uganda as a role model for pandemic containment in Africa [J]. Am. J. Public Health 110(12), 1800–2 (2020).

Noahsen P., Faber L. L., Isidor S., et al. The COVID-19 pandemic in Greenland, epidemic features and impact of early strict measures, March 2020 to June 2022 [J]. European communicable disease bulletin, 28(29) (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z., Y.Z., S.H, T.Z.and Y.D. wrote the main manuscript text and S.X., and Q.S. prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, J., Zhang, Y., He, S. et al. Accelerated global burden of depressive disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic from 2019 to 2021. Sci Rep 15, 9529 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93923-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93923-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The hippocampus as a central hub in ketamine’s antidepressant action: from molecules to circuit rewiring

Neuropsychopharmacology (2026)

-

Ketamine enantiomers and the gut microbiota: mechanisms, clinical implications, and future directions

Molecular Biology Reports (2026)

-

The invisible wounds of war: a study of insomnia and psychological distress among healthcare students in conflict-affected Syria

BMC Psychology (2025)