Abstract

In real applications of Reinforcement Learning (RL), such as robotics, low latency, energy-efficient and high-throughput inference is very desired. The use of sparsity and pruning for optimizing Neural Network inference, and particularly to improve energy efficiency, latency and throughput, is a standard technique. In this work, we conduct a systematic investigation of the application of these optimization techniques with popular RL algorithms, specifically Deep Q-Network and Soft Actor Critic, in different RL environments, including MuJoCo and Atari, which yields up to a 400-fold reduction in the size of neural networks. This work presents a systematic study on the applicability limits of using pruning and quantization to optimize neural networks in RL tasks, with a perspective of deployment in hardware to reduce power consumption and latency, while increasing throughput.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the last decade, neural networks (NNs) have driven significant progress across various fields, notably in deep reinforcement learning, highlighted by studies like1,2,3. This progress has the potential to make changes in many areas such as embedded devices, IoT and Robotics. Although modern Deep Learning models have shown impressive gains in accuracy, their large sizes pose limits to their practical use in many real-world applications4. These applications may impose requirements on energy consumption, inference latency, inference throughput, memory footprint, real-time inference, and hardware costs.

Numerous studies have attempted to make neural networks more efficient. These approaches can generally be classified into at least the following several groups4:

-

pruning5,

-

distillation8,

-

quantization5,

-

neural architecture search of efficient NN architectures9,

-

hardware and NN co-design10.

In addition, some works try to mix some of these methods11,12,13,14,15,16. The combination of methods could lead to substantial improvements in neural network efficiency. For example, the combination of 8-bit integer quantization and 10% sparsity may result in a 40x times decrease in memory footprint and a decrease in computational complexity achieved by using fewer arithmetical operations and using integer arithmetic. Furthermore, beyond efficiency gains, the introduction of sparsity may contribute to improved accuracy in neural networks. For example, it was shown in7,17,18 that sparse neural networks derived by pruning usually achieve better results than their dense counterparts with an equivalent number of parameters. Moreover, even sparse neural networks that contain 10% of the weights of the original network could sometimes achieve higher accuracy than dense neural networks19.

Several of the previously mentioned NN optimization methods find inspiration in neuroscience. In the brain, the presence of dense layers is not evident. Instead, the brain employs a mechanism similar to rewiring and pruning to eliminate unnecessary synapses20. As a result, neural networks in the brain are sparse and have irregular topology. Several works in neuroscience state that the brain represents and processes information in discrete/quantized form21,22. It could be justified that information stored in continuous form would inevitably be corrupted by the noise present in any physical system23. It is impossible to measure a physical variable with infinite precision. Moreover, from the point of view of the Bayesian framework, quantization leads to stability in the representation of information and robustness to additive noise24.

It is well known that obtaining data from Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) is much more expensive in terms of energy and time compared to arithmetic operations and obtaining data from fast, but expensive Static Random Access Memory (SRAM)25. This problem is commonly known as the von Neumann problem26,27. The huge sizes of contemporary neural networks exacerbate this problem, making it difficult to achieve high Frames Per Second (FPS), low latency, and energy-efficient performance on modern hardware. The reduction of neural network sizes leads to the diminishing of data exchange between memory and processor and potentially results in higher performance and less energy consumption. Furthermore, a significant reduction in the size of the neural network can enable its placement in faster SRAM, contributing to a notable improvement in memory access latency and throughput (see Fig. 1). It should be noted that reducing memory accesses is much more significant for speeding up neural networks than just reducing arithmetic operations10.

However, there are only a few papers18,28 that apply these approaches to RL. To the best of our knowledge, there are no papers that attempt to mix them. While pruning and quantization are well-studied in classical Deep Learning, their application to RL introduces unique challenges and nuances. RL systems involve dynamic interactions with environments, non-stationary data distributions, and complex training pipelines that integrate exploration and policy updates - factors absent in traditional NN optimization techniques. These domain-specific characteristics complicate the transfer of classical neural network optimization techniques to RL, because, for example, pruning impacts exploration and quantization errors alter reward signal propagation. At the same time, many potential RL applications impose strong latency, FPS and energy limits. For example, in2 DeepMind applied RL for tokamak control, and it was necessary to achieve a remarkable 10kHz FPS to meet the operational requirements. Similarly, in3, the authors applied RL for drone racing. Drone control requires 100 HZ FPS for the RL network. Moreover, since the network inference was on board, strong restrictions are placed on energy consumption. These examples highlight the critical need for advancing optimization techniques in RL to meet the demanding performance criteria of various applications.

In this work, we apply a combination of quantization and pruning techniques to RL tasks. Pruning and subsequent quantization is a common approach to achieve greater network compression. While pruning alone can improve compression, its effectiveness is limited as excessive pruning degrades network performance. Quantization enables further compression after reaching the pruning limit, complementing the benefits of pruning. The primary goals were to showcase the possibility of dramatically improving the efficiency of actor networks trained using various RL algorithms and to investigate the applicability of NN optimization techniques and their combination in the RL context. The ultimate aim is to expand the applicability of these networks to a diverse range of embedded applications, particularly those with strong requirements for FPS, energy consumption, and hardware costs. Our findings indicate that it is feasible to apply quantization and pruning to Neural Networks trained by RL without loss in accuracy. Furthermore, sometimes we even observed improvements in accuracy after applying these optimization techniques. This suggests a promising avenue for optimizing RL-based actor networks for resource-constrained embedded applications without sacrificing performance.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section “Background”, we provide a concise overview of RL and two methods of neural network compression that we use in this work, namely, pruning and quantization. Section “Methods” provides details of the RL algorithms and environments, along with a comprehensive description of the training procedure. In Section “Experiments”, we describe the technical details of applying pruning and quantization to the networks under study. Section “Results” presents results of applying compression methods. In Sections “Discussion” and “Conclusion”, we discuss and summarize our findings.

Background

This section introduces the RL notation used in the experiment and provides an overview of pruning and quantization methods, the combination of which is investigated in the subsequent experiment.

RL

In RL29, an agent interacts with an environment by sequentially selecting actions a in response to the current environment state s. After making a choice, it transitions to a new state \(s'\) and receives a reward r. The agent’s goal is to maximize the sum of discounted rewards.

This is formalized as a Markov decision process defined as a tuple (S, A, P, R), where S is the set of states, and A is the set of actions. P is the function that describes the transition between states; \(P(s' | s, a) = Pr(s_{t+1} = s' | s_t = s, a_t = a)\), , i.e., is the probability of entering state \(s'\) at the next step when selecting action a in state s. \(R = R(s, a, s')\) is the reward function that determines the reward an agent will receive when transitioning from state s to state \(s'\) by selecting an action a.

The policy \(\pi _\theta\) defines the probability that an agent selects an action a in state s. \(\theta\) denotes policy parameters.

Pruning

Pruning is the process of removing unnecessary connections30,31. There are many different approaches for finding sparse neural networks and several criterion for classifying algorithms. They could be classified into the following categories:

-

We fully train a dense model, prune it and finetune32. In this approach, we prune a trained dense network and then finetune remaining weights during additional training steps.

-

Gradually prune dense model during training33. Here we start with a dense network and then, according to a specific schedule, which determines the number of weights cut off at each pruning step, we gradually prune the network.

-

Sparse training with a sparse pattern selected a priori. In this approach we attempt to prune a dense network at step 034,35 and keep the topology fixed throughout training. It is worth to note, that training a sparse randomly pruned NN is difficult and leads to much worse results than training a NN with a carefully chosen sparse topology19.

-

Sparse training with a rewiring during training. We start with a sparse NN and maintain sparsity level throughout training, but with the possibility to rewire weights36,37,38, i.e. to add and to remove connections.

On the other side, they could be classified by the pruning criterion. This criterion is used for selecting pruning weights. These criteria are grouped into Hessian-based criteria30,31,39, magnitude-based32 and Bayesian-based criteria40,41,42. The most widely used in practical applications is the magnitude-based approach. In this approach, the smallest by the module weights are pruned.

In addition, it is important to distinguish between structured and unstructured pruning. During structural pruning, we remove parameters united in groups (e.g. entire channels, rows, blocks) in order to exploit classical AI hardware efficiently. However, it is important to note that at higher levels of sparsity, structured pruning methods have been observed to lead to a decrease in model accuracy. On the other hand, unstructured pruning does not consider the resulting pattern. This means that parameters are pruned independently, without considering their position or relationship within the model. Networks pruned with unstructured sparsity usually retain more accuracy compared to structurally pruned counterparts with a similar level of sparsity.

Another important issue is how to distribute pruning weights among layers. There are several approaches:

-

Global. In this approach, we consider all weights together and select weights for pruning among all weights of the model.

-

Local uniform. Here, in each layer, we prune the same fraction of weights.

-

Local Erdős-Rényi37,38. Here we make a non-uniform distribution of weights across layers according to the formulae:

\(s^l = \epsilon * \frac{n^l +n^{l+1}}{n^l * n^{l+1}}\) - for MLP, where \(s^l\) is the fraction of the unpruned weights in the layer l, \(n^l\) is the dimension of the layer l, \(\epsilon\) is a coefficient for controlling the sparsity level,

\(s^l = \epsilon * \frac{n^l + n^{l+1} + w^l + h^l}{n^l * n^{l+1} * w^l * h^l}\) - for CNNs, where \(s^l\) is the fraction of the unpruned weights, \(n^l\) is the number of channels in the layer l, \(w^l\) is the width of the convolution kernel, \(h^l\) is the height of the convolution kernel, \(\epsilon\) is a coefficient to control the sparsity level.

Generally, it is made to reduce pruning in the input and output layers, in which usually there is less number of weights due to small input / output dimensions and these layers are more sensible to pruning32.

The performance of different pruning techniques for the RL domain was investigated in18. All training approaches started from sparse NN were usually worse in performance in comparison to the gradual pruning scheme proposed in33.

It was also shown in18 that the performance in almost all MuJoCo environments doesn’t degrade even on sparsity levels of 90-95 percents. Another important consequence from18 is that in RL domain sparse NNs could sometimes achieve better performance then their dense counterparts.

Quantization

Generally, quantization is the process of mapping a range of input values to a smaller set of discrete output values. Quantization of neural networks reduces the precision of neural network weights and/or activations. This reduces memory footprint and consequently data transfer from memory to processor. Moreover, this enables the use of low-precision/integer arithmetic that supported by modern computational devices for neural networks including GPUs, TPUs43, NorthPole44, and many others. Neural network quantization is a mature field. There are many types of quantization approaches. A comprehensive overview of quantization was presented in4. Here, we briefly discuss some important types of quantization.

Generally, there are two main types of quantization4:

-

Quantization aware training (QAT). During training, QAT introduces a non-differentiable quantization operator that quantizes model parameters after each update. However, the weight update and the backward pass are performed in floating point precision. It is crucial to conduct the backward pass using floating point precision as allowing gradient accumulation in quantized precision may lead to zero-gradients or gradients with significant errors, particularly when utilizing low-precision. The reasons for the possibility of using a non-differentiable quantized operator are explained in45. QAT works effectively in practice except for ultra low-precision quantization techniques like binary quantization4.

-

Post-training quantization (PTQ). An alternative to the QAT is to quantize an already trained model without any fine-tuning. PTQ has a distinct advantage over QAT because it can be used in environments with limited or unlabeled data. Nonetheless, this potentially comes with a cost of decreased accuracy compared to QAT, especially for low-precision quantization techniques.

Also, it is necessary to choose a quantization precision. Some methods provide even 1–2 bit precision46,47, however, this usually leads to a strong decrease in accuracy. At the same time, many works show the possibility of using 8-bit precision almost without any decrease in quality.

Moreover, quantization techniques are subdivided by approaches for choosing clipping ranges for weights4:

-

Quantization could be symmetric or asymmetric, depending on the symmetry of the clipping interval.

-

Uniform and non-uniform. In uniform quantization, the input range is divided into equal-sized intervals or steps. In non-uniform the step size is adjusted based on the characteristics of the input signal. Smaller steps are used in regions with more signal activity, and larger steps are used in regions with less activity. Non-uniform quantization may achieve higher accuracy, however it is more complex to implement in hardware.

-

Quantization granularity. In convolutional layers, different filters could have different ranges of values. This requires to choose the granularity of how the clipping ranges will be calculated. Generally, there are the next approaches: layerwise (tensorwise), channelwise and groupwise. In layerwise, we calculate one clipping range for all weights in a layer. In channelwise, the quantization is applied independently to each channel within a layer. Channelwise quantization allows for more fine-grained control over the quantization process, considering the characteristics of individual channels. In groupwise quantization, which lay somewhere between the previous two approaches, channels are grouped together, and quantization is applied to each group.

In28 authors analysed both QAT and PTQ 8-bit symmetric quantization for RL tasks. They achieve comparable results with a fully precision training procedure. Moreover, they show that sometimes quantization yields better scores, possibly due to the implicit noise injection during the quantization.

Methods

This section provides a comprehensive description of the methodology. Specifically, it outlines the optimized RL algorithms, environments and training procedure.

RL algorithms

For testing optimization algorithm, we chose Soft Actor Critic (SAC)48 and Deep Q-Network (DQN)1 algorithms due to their popularity and high performance. SAC belongs to the family of actor-critic off-policy algorithms, and DQN belongs to the family of value-based off-policy algorithms.

RL environments

We experimented within two RL environments: Mujoco suite49 and Atari games50. These environments were chosen because they offer diverse and well-studied benchmarks that enable a comprehensive evaluation of RL algorithms.

MuJoCo (Multi-Joint dynamics with Contact) environments belong to the class of continuous control environments. Generally, in MuJoCo environments it is necessary to control the behavior (e.g. walking) of biomimetic mechanisms formed within multiple joint rigid bodies. The observations of these environments are vectors of real numbers with dimensions from 8 to 376, that include information about the state of the agent and the world (e.g., positions, velocities, joint angles). The actions (inputs) for these environments are also vectors of real values with dimensions from 1 to 17. They define how the agent can interact with the environment (for example, applying forces or torques to joints).

Atari environments provide a suite of classic Atari video games as testbeds for reinforcement learning algorithms. Unlike environments that provide low-dimensional state representations, Atari games offer high-dimensional observation spaces directly from the game’s pixel output. Actions in Atari games are typically discrete, corresponding to the joystick movements and button presses available on the original Atari 2600 console.

Training procedure

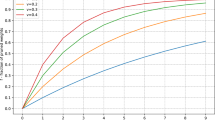

Since we want to improve the inference, we pruned for SAC only an actor-network. In DQN there is no separation of actor and critic. We start training at the environment step \(t_0\), then according to18 the pruning begins at the environment step \(t_s\) and continues until the environment step \(t_{f}\). We gradually prune a Neural Network every \(\Delta t\) step according to the schedule presented in33 during n steps. This pruning scheme involves gradual transformation of a dense network into a sparse one with sparsity \(s_{t}\) according to formula (1) via weight magnitudes. When another pruning step is completed, we are leaving the pruned weights equal to zero for the remainder of the training. The training of the pruned NN continues until the environment step \(t_p\). The plot of the proposed sparsity schedule is presented in Fig. 2.

For quantizing the pruned NN, after step \(t_p\) we start to apply symmetric, uniform 8-bit QAT to the remaining weights until step \(t_q\). For fully connected layers, we used layerwise quantization. For convolution layers, we used channelwise quantization.

General scheme of training. A randomly initialized neural network is trained for 20% of the total steps in a classical manner. Further, during the 20-80% of training, gradual pruning with n steps is applied. Then pruning is turned off and from 80 to 100% of steps the network is trained again in the classical way. If quantization is required, an additional 20% of training steps (from 100% to 120%) are performed with 8-bit quantization.

Experiments

We experiment within the following RL environments from the MuJoCo suite: HalfCheetah-v4, Hopper-v4, Walker2d-v4, Ant-v4, Humanoid-v4, Swimmer-v4; and Atari games: Pong-v4, Boxing-v4, Tutankham-v4, and CrazyClimber-v4. We repeat each experiment for MuJoCo environments with 10 different seeds. For Atari games, we repeat each experiment with 5 different seeds.

For MuJoCo environments we use the SAC algorithm with a multilayer perceptron (MLP) with two hidden layers with 256 neurons in each of them. The sizes of the input and output layers depend on the environment.

For Atari environments, we used the DQN algorithm with two different types of neural networks: classical three-layer CNN1 and ResNet51 based networks with three residual blocks52. All parameters are provided in the Supplementary material, see Tables 1–3.

For both algorithms, we used their implementations from the StableBaselines353 library for our experiments.

For each environment, we train sparse policies with different levels of pruning: 50 (× 2), 70 (× 3.3), 80 (× 5), 90 (× 10), 95 (× 20) and 98 (× 50) percent. For MuJoCo environments, we add an additional sparsity level equal to 99 (× 100) percent. For each sparsity level, we train NN with and without quantization. We start pruning after completing 20 percent (\(t_s = 0.2 * total\_steps\)) of steps and finish it after completing 80 percent (\(t_f = 0.8 * total\_steps\)) of steps. For SAC we use 600 iterations of pruning, and for both DQN we use 300 iterations of pruning. We quantize a neural network after completing the training procedure during an additional 20 percent (\(t_q = 1.2 * total\_steps\)) of steps (see Fig. 3).

In addition to the classical RL metric of reward, we also measure the degree of neural network compression achieved by applying pruning and quantization techniques. As mentioned in Section 1, a high degree of network compression is a critical factor for hardware deployment.

In the experimental phase, we employed the Nvidia DGX system. A single experiment, conducted for one environmental setting, required an average of five days of continuous computation for evaluating all possible levels of sparsity, both with and without quantization. In total, the computational duration for all experiments amounted to approximately 40 days.

Results

Figures 4, 5, 6 present the performance of pruned and/or quantized neural networks in various environments.

We see in Fig. 4 that for the most number of MuJoCo environments (except HalfCheetah) we could prune and quantize up to 98 percent without loss of quality, leading to a 200x decrease in the size of neural networks: 4x by quantization, 50x by pruning. Even for HalfCheetah we could prune 80 % of the weights and quantize them, which leads to a 20x decrease in the size of the neural network. For some environments e.g. Hopper and Swimmer we could prune 99 percent of weights and quantize them without the loss in quality which leads to a 400x decrease in the size of the neural network. Furthermore, quantization + pruning usually slightly outperforms pruning, which leads to better results even in comparison to the dense model. These finding are provided in details in the Supplementary material, Tables 4–9.

In comparison to the results presented in18 we achieved high levels of sparsity (up to 99 percent) without the loss in quality for the SAC algorithm. This can be explained by our strategy of pruning only the actor model, as opposed to pruning both the actor and the critic in18. The authors of18 conducted experiments to determine the optimal parameter ratio between the actor and critic for a given parameter budget. They came to the conclusion that the actor parameters are less significant than the critic parameters, which is consistent with our results. We chose to prune only the actor because only its sparsity is important for efficient inference.

For classical CNN-based DQN for Atari environments, we see in Fig. 5 that for all environments, we could prune and quantize up to 80 percent without the loss of quality, which leads to a 20x decrease in the size of optimized neural networks. For Pong and Tutankham we could prune and quantize up to 95 percent of sparsity which leads to a total 100x decrease in the size of neural networks. The characteristics of the neural networks are given in the Supplementary material, Tables 10–13.

For ResNet-based DQN for Atari environments, we see in Fig. 6 the possibility to prune and quantize up to 95 percent, without the significant loss in quality, that leads to a 80x decrease in the size of neural networks. For Pong and Tutankham we could prune and quantize up to 98 percent of sparsity which leads to a 200x decrease in the size of neural networks. It is worth noting that ResNet-based networks are much more suitable for pruning and quantizing which coincide with the findings in18. The details about parameters of the neural networks are provided in the Supplementary material, Tables 14–17.

Results for SAC algorithm applied to MuJoCo suite environments. The x-axes of the figures denote the neural network sparsity degree; the y-axes denote the performance – the reward received by an agent. The blue line shows the performance of the pruned network, and the red line shows the performance of the pruned and quantized network. The dotted purple line shows the performance of the quantized-only network, the green dashed line shows the performance of the default network.

Results for DQN algorithm based on the CNN applied to Atari environments. The x-axes of the figures denote the neural network sparsity degree; the y-axes denote the performance – the reward received by an agent. The blue line shows the performance of the pruned network and the red line shows the performance of the pruned and quantized network. The dotted purple line shows the performance of the quantized-only network, green dashed line shows the performance of the default dense and fully precision network.

Results for DQN algorithm based on the ResNet applied to Atari environments. The x-axes of the figures denote the neural network sparsity degree; the y-axes denote the performance—the reward received by an agent. The blue line shows the performance of the pruned network, and the red line shows the performance of the pruned and quantized network. The dotted purple line shows the performance of the quantized only network, green dashed line shows the performance of the default dense and fully precision network.

Discussion

Generally, there is great interest in neuromorphic intelligence 27,54, which takes advantage of different aspects of biological neural systems. These include novel architectures and learning algorithms 55,56,57,58,59,60. On the one hand, these modern neuromorphic networks are used in neuroscience research, allowing us to explain or replicate emergent cognitive phenomena. On the other hand, they contribute to developing more efficient computing frameworks which would enable one to reduce the computational resources required for training and implementing neural networks. In some sense, quantization and pruning could be considered as neuromorphic approaches. In the brain, there are no fully connected layers20 and a strong regular structure compared to modern NN. Also, it seems impossible to store values with the precision provided by the 32-bit floating points in highly noisy cell environment4,21,22.

Minimizing the size of NNs mitigates the von Neumann problem of modern hardware by reducing the exchange between memory and processor. Moreover, it is often possible to locate the obtained smallified NNs in on-chip memory. That could lead to very high inference speeds, low energy consumption, and low latencies. It was shown that this desire could be achieved even on classical CPUs by the Neural Magic company for classical DL domains. Moreover, the recent IBM chip NorthPole44 based totally on near-memory computing and storing weights and activations in the on-chip memory, could be enhanced by optimization algorithms proposed here.

Conclusion

In this study, we explored the use of quantization and pruning techniques in RL tasks to enhance the efficiency of neural networks trained with various RL algorithms. We demonstrated the large redundancy (up to 400x) in the neural network size used for popular RL tasks. By providing the possibility of significantly reducing neural networks trained by RL algorithms, we expand their potential applications in practical domains like Edge AI, real-time control, robotics, and many others. Our findings reveal that applying quantization and pruning to RL-trained networks is not only feasible without accuracy loss but can also sometimes improve accuracy, offering a promising strategy for optimizing RL-based actor networks for resource-constrained environments. However, it is worth noting that the maximum profit could be achieved in a smart co-design of algorithms and hardware.

Data availability

The materials used in the current study including code and learning curves are available at https://github.com/rudimiv/NNCompression4RL.

References

Mnih, V. et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 518, 529–533 (2015).

Degrave, J. et al. Magnetic control of tokamak plasmas through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 602, 414–419 (2022).

Kaufmann, E. et al. Champion-level drone racing using deep reinforcement learning. Nature 620, 982–987 (2023).

Gholami, A. et al. A survey of quantization methods for efficient neural network inference. http://arxiv.org/abs/2103.13630 (2021).

Liang, T., Glossner, J., Wang, L., Shi, S. & Zhang, X. Pruning and quantization for deep neural network acceleration: A survey. Neurocomputing 461, 370–403 (2021).

Yousefzadeh, A. et al. Asynchronous spiking neurons, the natural key to exploit temporal sparsity. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 9, 668–678 (2019).

Ivanov, D. A., Larionov, D. A., Kiselev, M. V. & Dylov, D. V. Deep reinforcement learning with significant multiplications inference. Sci. Rep. 13, 20865 (2023).

Hinton, G., Vinyals, O. & Dean, J. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. http://arxiv.org/abs/1503.02531 (2015).

Ren, P. et al. A comprehensive survey of neural architecture search: Challenges and solutions. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 54, 1–34 (2021).

Han, S. et al. Eie: Efficient inference engine on compressed deep neural network. ACM SIGARCH Comput. Arch. News 44, 243–254 (2016).

Han, S., Mao, H. & Dally, W. J. Deep compression: Compressing deep neural networks with pruning, trained quantization and huffman coding. http://arxiv.org/abs/1510.00149 (2015).

Chen, Y.-H., Emer, J. & Sze, V. Eyeriss: A spatial architecture for energy-efficient dataflow for convolutional neural networks. ACM SIGARCH Comput. Arch. News 44, 367–379 (2016).

Kwon, H., Samajdar, A. & Krishna, T. Maeri: Enabling flexible dataflow mapping over dnn accelerators via reconfigurable interconnects. ACM SIGPLAN Not. 53, 461–475 (2018).

Mirmahaleh, S. Y. H. & Rahmani, A. M. Dnn pruning and mapping on noc-based communication infrastructure. Microelectron. J. 94, 104655 (2019).

Parashar, A. et al. Scnn: An accelerator for compressed-sparse convolutional neural networks. ACM SIGARCH Comput. Arch. News 45, 27–40 (2017).

Mirmahaleh, S. Y. H., Reshadi, M., Bagherzadeh, N. & Khademzadeh, A. Data scheduling and placement in deep learning accelerator. Clust. Comput. 24, 3651–3669 (2021).

Blalock, D., Ortiz, J. J. G., Frankle, J. & Guttag, J. What is the state of neural network pruning? http://arxiv.org/abs/2003.03033 (2020).

Graesser, L., Evci, U., Elsen, E. & Castro, P. S. The state of sparse training in deep reinforcement learning. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 7766–7792 (PMLR, 2022).

Frankle, J. & Carbin, M. The lottery ticket hypothesis: Finding sparse, trainable neural networks. http://arxiv.org/abs/1803.03635 (2018).

Hudspeth, A. J., Jessell, T. M., Kandel, E. R., Schwartz, J. H. & Siegelbaum, S. A. Principles of neural science (Health Professions Division, McGraw-Hill, 2013).

Tee, J. & Taylor, D. P. Is information in the brain represented in continuous or discrete form?. IEEE Trans. Mol. Biol. Multi-Scale Commun. 6, 199–209 (2020).

VanRullen, R. & Koch, C. Is perception discrete or continuous?. Trends Cogn. Sci. 7, 207–213 (2003).

Faisal, A. A., Selen, L. P. & Wolpert, D. M. Noise in the nervous system. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 292–303 (2008).

Sun, J. Z., Wang, G. I., Goyal, V. K. & Varshney, L. R. A framework for bayesian optimality of psychophysical laws. J. Math. Psychol. 56, 495–501 (2012).

Horowitz, M. 1.1 computing’s energy problem (and what we can do about it). In 2014 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference Digest of Technical Papers (ISSCC), 10–14 (IEEE, 2014).

Backus, J. Can programming be liberated from the von neumann style? A functional style and its algebra of programs. Commun. ACM 21, 613–641 (1978).

Ivanov, D., Chezhegov, A., Kiselev, M., Grunin, A. & Larionov, D. Neuromorphic artificial intelligence systems. Front. Neurosci. 16 (2022).

Krishnan, S. et al. Quarl: Quantization for fast and environmentally sustainable reinforcement learning. http://arxiv.org/abs/1910.01055 (2019).

Sutton, R. S. & Barto, A. G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction (MIT press, 2018).

LeCun, Y., Denker, J. S. & Solla, S. A. Optimal brain damage. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., 598–605 (1990).

Hassibi, B. & Stork, D. G. Second Order Derivatives for Network Pruning: Optimal Brain Surgeon (Morgan Kaufmann, 1993).

Han, S., Pool, J., Tran, J. & Dally, W. Learning both weights and connections for efficient neural network. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 28 (2015).

Zhu, M. & Gupta, S. To prune, or not to prune: exploring the efficacy of pruning for model compression. http://arxiv.org/abs/1710.01878 (2017).

Lee, N., Ajanthan, T. & Torr, P. H. Snip: Single-shot network pruning based on connection sensitivity. http://arxiv.org/abs/1810.02340 (2018).

Wang, C., Zhang, G. & Grosse, R. Picking winning tickets before training by preserving gradient flow. http://arxiv.org/abs/2002.07376 (2020).

Bellec, G., Kappel, D., Maass, W. & Legenstein, R. Deep rewiring: Training very sparse deep networks. http://arxiv.org/abs/1711.05136 (2017).

Mocanu, D. C. et al. Scalable training of artificial neural networks with adaptive sparse connectivity inspired by network science. Nat. Commun. 9, 2383 (2018).

Evci, U., Gale, T., Menick, J., Castro, P. S. & Elsen, E. Rigging the lottery: Making all tickets winners. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 2943–2952 (PMLR, 2020).

Theis, L., Korshunova, I., Tejani, A. & Huszár, F. Faster gaze prediction with dense networks and fisher pruning. http://arxiv.org/abs/1801.05787 (2018).

Molchanov, D., Ashukha, A. & Vetrov, D. Variational dropout sparsifies deep neural networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 2498–2507 (PMLR, 2017).

Dai, B., Zhu, C., Guo, B. & Wipf, D. Compressing neural networks using the variational information bottleneck. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 1135–1144 (PMLR, 2018).

Louizos, C., Ullrich, K. & Welling, M. Bayesian compression for deep learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30 (2017).

Jouppi, N. P. et al. A domain-specific supercomputer for training deep neural networks. Commun. ACM 63, 67–78 (2020).

Modha, D. S. et al. Ibm northpole neural inference machine. In 2023 IEEE Hot Chips 35 Symposium (HCS), 1–58 (IEEE Computer Society, 2023).

Yin, P. et al. Understanding straight-through estimator in training activation quantized neural nets. http://arxiv.org/abs/1903.05662 (2019).

Courbariaux, M., Bengio, Y. & David, J.-P. Binaryconnect: Training deep neural networks with binary weights during propagations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 28 (2015).

Hubara, I., Courbariaux, M., Soudry, D., El-Yaniv, R. & Bengio, Y. Binarized neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 29 (2016).

Haarnoja, T., Zhou, A., Abbeel, P. & Levine, S. Soft actor-critic: Off-policy maximum entropy deep reinforcement learning with a stochastic actor. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 1861–1870 (PMLR, 2018).

Todorov, E., Erez, T. & Tassa, Y. Mujoco: A physics engine for model-based control. In 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 5026–5033 (IEEE, 2012).

Bellemare, M., Veness, J. & Bowling, M. Investigating contingency awareness using atari 2600 games. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 26, 864–871 (2012).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 770–778 (2016).

Espeholt, L. et al. Impala: Scalable distributed deep-rl with importance weighted actor-learner architectures. In International conference on machine learning, 1407–1416 (PMLR, 2018).

Raffin, A. et al. Stable-baselines3: Reliable reinforcement learning implementations. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 22, 1–8 (2021).

Chen, B. & Yang, S. Neuromorphic Intelligence: Learning, Architectures and Large-Scale Systems (Springer, 2024).

Yang, S. & Chen, B. Effective surrogate gradient learning with high-order information bottleneck for spike-based machine intelligence. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. (2023).

Yang, S., Wang, H. & Chen, B. Sibols: robust and energy-efficient learning for spike-based machine intelligence in information bottleneck framework. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. (2023).

Yang, S. & Chen, B. Snib: improving spike-based machine learning using nonlinear information bottleneck. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. (2023).

Yang, S. et al. Spike-driven multi-scale learning with hybrid mechanisms of spiking dendrites. Neurocomputing 542, 126240 (2023).

Pugavko, M. M., Maslennikov, O. V. & Nekorkin, V. I. Multitask computation through dynamics in recurrent spiking neural networks. Sci. Rep. 13, 3997 (2023).

Maslennikov, O. V., Pugavko, M. M., Shchapin, D. S. & Nekorkin, V. I. Nonlinear dynamics and machine learning of recurrent spiking neural networks. Phys. Uspekhi 65, 1020–1038 (2022).

Voevodin, V. V. et al. Supercomputer lomonosov-2: Large scale, deep monitoring and fine analytics for the user community. Supercomput. Front. Innov. 6, 4–11 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The research is carried out using the equipment of the shared research facilities of HPC computing resources at Lomonosov Moscow State University61 and Cifrum IT infrastructure. The work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation, project 23-72-10088, https://rscf.ru/project/23-72-10088/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DI, DL, OM, and VV contributed to the conception and design of the study. DI and DL contributed equally. OM and VV were co-senior authors. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ivanov, D.A., Larionov, D.A., Maslennikov, O.V. et al. Neural network compression for reinforcement learning tasks. Sci Rep 15, 9718 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93955-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93955-w