Abstract

Unsupervised fault diagnosis methods for rotating machinery are gaining attention but face challenges such as feature extraction from vibration signals, aligning distributions between source and target domains, and managing domain shifts. This paper proposes a novel unsupervised transfer learning method that integrates the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) attention mechanism to enhance useful features while suppressing redundant ones. An Integrated Distribution Alignment Framework (IDAF) is introduced, which employs the Joint Adaptation Network (JAN) approach to construct a local maximum mean discrepancy in conjunction with Correlation Alignment (CORAL) to improve distribution alignment between domains. Moreover, to enhance feature learning and obtain more distinct features, the authors utilize a novel discriminative feature learning method called I-Softmax loss. This method can be optimized in a manner similar to the traditional Softmax loss while providing improved classification performance. Finally, deep adversarial training is applied between the source and target domains to adaptively optimize the target domain network parameters, reducing domain shift and improving fault classification accuracy. Experimental validation using four sets of bearing faults and six sets of gear faults demonstrates the superior performance of the proposed method in unsupervised fault diagnosis tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rotating machinery, as an indispensable core component in modern industry, directly affects production efficiency, safety, and economic benefits through its reliability and operational stability. Especially in the automotive manufacturing and energy sectors, the quality and safety standards for bearings and gears are also subject to rigorous oversight. These machines operate under long-term, high-load conditions and face severe consequences if faults are not detected in time, potentially leading to significant economic losses or even personal injuries1,2.

With the advancement of the manufacturing industry, the demand for intelligent maintenance has become increasingly prominent, making fault diagnosis technologies a crucial means to enhance equipment reliability and safety3. Traditional fault diagnosis methods primarily rely on the experience and rule-making of specialized technicians. These methods are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and suffer from subjectivity and limitations. However, with the rapid development of big data technologies and deep learning, data-driven fault diagnosis methods have shown tremendous potential4,5,6. Deep learning models are capable of learning and extracting complex feature representations from vast amounts of raw data, enabling efficient and accurate fault classification and prediction through training7.

In recent years, significant progress has been made in the research of intelligent fault diagnosis technologies8. Traditional signal processing-based methods, while providing certain fault detection capabilities, often fail to meet the requirements of real-time operation and high accuracy in complex industrial environments. In contrast, deep learning-based intelligent fault diagnosis methods can automatically extract effective features from raw sensor data, overcoming the limitations of manual feature extraction in traditional methods. For example, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) have been widely applied in fault diagnosis. When used for bearing fault detection, CNNs significantly improve diagnostic accuracy by constructing time-frequency images and utilizing CNNs for feature extraction and classification. The Coupled Autoencoder (CAE) model, which captures cross-modal information from different sensors, further enhances the robustness of fault diagnosis.

Despite the significant achievements of deep learning-based methods in fault diagnosis, several challenges remain in practical applications. Firstly, since rotating machinery operates under varying working conditions, the distribution characteristics of vibration signals and other sensor data differ across these conditions, making models trained under a single condition difficult to generalize across multiple operating conditions9. Additionally, the high cost of large-scale data collection and labeling limits the feasibility of traditional supervised learning methods. Therefore, achieving effective unsupervised or semi-supervised fault diagnosis across different working conditions has become a key focus of current research10,11.

To address these challenges, Transfer Learning (TL) has been widely applied in the field of fault diagnosis as an effective strategy12. TL alleviates the issue of limited data in the target domain by transferring knowledge from the source domain. The concept of TL originated in the field of computer vision and refers to utilizing known data from source tasks to improve the learning process in target tasks. The key advantage of TL lies in its ability to leverage the abundant data from the source domain to enhance the learning of the target task, even when there is a scarcity of target domain data.TL primarily includes three strategies: Inductive Learning, Transductive TL, and Unsupervised TL13. Inductive Learning is commonly applied in multi-task learning and self-learning scenarios, where shared knowledge between the source and target tasks is used to improve the efficiency of learning in the target task. Transductive TL, on the other hand, directly transfers knowledge from the source task to assist in learning for the target task, and it typically works best when the relationship between the source and target tasks is relatively close.

Domain Adaptation is a key branch of TL, especially when there are distribution discrepancies between the source and target tasks. In such cases, domain adaptation techniques are particularly important. Common domain adaptation methods include feature-mapping-based transfer learning techniques, such as Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD)14, which have been widely used to minimize the distribution difference between the source and target domains. For instance, Li et al. proposed Transfer Component Analysis (TCA)15, which uses MMD for feature mapping, effectively improving the performance and robustness of fault diagnosis models. Furthermore, joint distribution-based transfer learning methods, such as Joint Distribution Adaptation (JDA)16 and Correlation Alignment (CORAL)17, have also been proposed and shown promising results. These methods improve diagnostic performance across different operating conditions by reducing the distribution discrepancy between the source and target domains.

Adversarial learning techniques have been widely applied across various fields, particularly in transfer learning and domain adaptation, achieving significant progress. Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN)18, introduced by Goodfellow et al., optimize through a game-theoretic process between a generator and a discriminator, enabling the generator to produce synthetic data that is indistinguishable from real data. In domain adaptation tasks, the Domain-Adversarial Neural Network (DANN) method19, proposed by Ganin et al., introduces a domain discriminator to align the feature distributions between the source and target domains, enabling effective knowledge transfer. The Conditional Domain-Adversarial Network (CDAN) further enhances adversarial learning by incorporating a conditional domain discriminator, which is based on the cross-covariance between source domain features and classifier predictions, allowing for more precise capture of domain differences20.

Moreover, adversarial learning has been extensively researched and has yielded promising results in transfer learning. For instance, Cycle GAN introduces cycle consistency loss, significantly improving the accuracy of data distribution alignment, particularly in image-to-image translation tasks21. Adversarial Autoencoders, on the other hand, employ adversarial training to generate more meaningful low-dimensional representations, thereby enhancing the model’s adaptability to cross-domain data. Overall, the successful application of adversarial learning techniques in transfer learning and domain adaptation, especially in scenarios with scarce data or significant distributional differences, provides effective solutions for fault diagnosis and prediction in intelligent devices.

Furthermore, designing effective loss functions22 and network architectures is a key research direction in discriminative feature learning23, as advancements in these areas directly impact the performance of models in classification and recognition tasks. Traditional approaches use Softmax, while contemporary methods include L-Softmax and A-Softmax, which enhance the model’s classification ability by mapping features into angular space. However, these methods face challenges during optimization, especially because of the non-linear nature of the cosine function, which complicates and destabilizes the optimization process. Cho et al.24 proposed a novel network architecture that introduces a Maximum Classifier Discrepancy (MCD) adversarial approach to improve the model’s distinguishing abilities. This method aims to optimize feature representation by increasing the model’s complexity and learning capability. However, the adversarial mechanism may introduce instability in task scores, potentially affecting the model’s practical application performance.

Despite the successful results achieved by the aforementioned methods in various domains and transfer tasks, they still overlook several important factors and face the following issues: (1) Traditional convolutional neural networks (CNN) have limitations in processing signals due to insufficient contextual convolutional perception and learnable parameters, which may lead to interference from irrelevant or noisy factors.(2) Existing transfer learning fault diagnosis methods are limited to feature mapping-based or domain-adversarial strategies. The former primarily focuses on reducing distribution differences between feature spaces, while the latter emphasizes learning and optimizing feature representations through end-to-end deep learning models. (3) Current joint distribution methods encounter difficulties in managing domain confusion and have trouble effectively minimizing discrepancies in feature distribution across various data domains. (4) Existing diagnostic methods have not fully accounted for the importance of learning discriminative features.

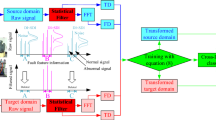

To tackle the issues mentioned above, this paper introduces the IADTLN network, which consists of the SE attention mechanism, Integrated Distribution Alignment Framework, I-Softmax loss algorithm, and CDAN. In IDAF, JAN and CORAL are integrated to form a novel distribution discrepancy metric aimed at alleviating domain confusion. Additionally, an entropy-conditioned variant of CDAN (CDAN + E) is incorporated to achieve a higher degree of domain confusion. To achieve greater diagnostic accuracy and acquire more distinct features, the I-Softmax loss algorithm and SE attention mechanism are also introduced. Experimental results show that the proposed framework successfully addresses the aforementioned problems. Compared with various unsupervised fault diagnosis methods, the proposed approach demonstrates better convergence and robustness, along with higher diagnostic accuracy. The primary contributions of this paper include the following:

-

(1)

This paper presents a novel network combining integrated distribution alignment framework (IDAF) with an entropy-conditioned variant of Conditional Domain-Adversarial Networks for unsupervised transfer learning in rotating machinery fault diagnosis. This integration enhances domain adaptation by improving knowledge transfer across domains.

-

(2)

To more accurately measure distribution differences, we propose an integrated distribution alignment framework that combines JAN and CORAL with varying parameter configurations, taking into account both the mean and covariance in the feature space. This approach effectively reduces domain discrepancies and enhances the performance of domain adaptation tasks.

-

(3)

This study the I-Softmax loss with flexible margins to improve feature separability, and integrate the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) attention mechanism to enhance feature representation by emphasizing useful features and suppressing redundant ones. These innovations significantly improve diagnostic accuracy.

Preparation

Problem definition

In transfer learning research, the objective is to leverage labeled data from the source domain to forecast the categories of unlabeled data within the target domain, with a particular focus on cases where the fault categories in both domains are the same. In this framework, the source domain is characterized as a labeled dataset employed for model training, whereas the target domain comprises unlabeled data collected under varying operating conditions. A crucial focus of the study is to accurately determine the categories of samples in the target domain by establishing the probability distributions and feature matrices for both domains, thus facilitating effective transfer learning. To expand on this topic, the authors present the following definitions.

(1)Here, \(x_{s}\) denotes the source domain, \(x_{s} ^{{\left( i \right)}}\) represents the \(i\) sample, \(x_{s} = \cup _{{i = 1}}^{{n_{s} }} x_{s}^{{\left( i \right)}}\) represents the union of all samples, \(y_{s}^{{\left( i \right)}}\) denotes the label of the \(i\) sample, \(y_{s} = \cup _{{i = 1}}^{{n_{s} }} y_{s}^{{\left( i \right)}}\) represents the union of all different labels, and \(n_{s}\) indicates the total number of source domain samples.

(2) Furthermore, in the absence of labels for the target domain, it is defined as follows: where \(x_{t}\) denotes the target domain, \(x_{t}^{{\left( i \right)}}\) represents the \(i\) sample, \(x_{t} = \cup _{{i = 1}}^{{n_{t} }} x_{t}^{{\left( i \right)}}\) represents the aggregation of all samples, and \(x_{t} = \cup _{{i = 1}}^{{n_{t} }} x_{t}^{{\left( i \right)}}\) denotes the overall count of samples in the target domain. Figure 1 presents a comparison of outcomes prior to and following domain adaptation.

Correlation alignment and joint maximum mean discrepancy

Correlation alignment

CORAL seeks to align the second-order covariance statistics between the two domains, even if their means may differ. In transfer learning, CORAL seeks to align the covariance matrices between domains as follows:

where, \(\left\| . \right\|_{F}^{2}\) represents the squared Frobenius norm of the matrix. In Eq. (1), \(C_{t}\) and \(C_{s}\) denote the covariance matrices.

Where, 1 represents a column vector with all elements set to 1.

Joint adaptation networks

Joint Adaptation Networks (JAN) is a deep learning method designed for domain adaptation, aiming to achieve knowledge transfer by simultaneously learning feature representations from both the source and target domains. This method minimizes the domain disparity between the source and target domains to improve classification performance in the target domain. JAN takes advantage of Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) by employing Hilbert space representations of the joint distributions to calculate the two joint distributions for the source domain and target domain as follows: \(P_{s} \left( {X_{s} ,Y_{s} } \right)\) and \(P_{t} \left( {X_{t} ,Y_{t} } \right)\) . The resulting measure is referred to as Joint Maximum Mean Discrepancy (JMMD). Below are some key formulas used in JAN:

where, \(\phi\) represents the mapping function that maps the input data into the feature space, Where\(l\) represents the activations of the \(l\)-th layer for the source domain and the target domain, respectively. JAN achieves feature alignment between the source and target domains by minimizing the Joint Maximum Mean Discrepancy (JMMD). It integrates JMMD as a loss function, along with the classification task’s loss function for joint optimization. This method not only decreases the distribution disparity between domains in the feature space but also boosts the model’s classification performance in the target domain. This strategy effectively facilitates knowledge transfer, allowing the network to maintain source domain features while improving its adaptability to target domain features.

1. Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD):

2. Joint Maximum Mean Discrepancy (JMMD):

Proposed method

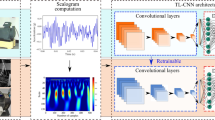

CNN framework

Due to the strong feature learning capabilities of CNN25, the authors have chosen CNN as the feature extractor. The network architecture is depicted in Table 1, with detailed parameters listed in Table 1. The architecture includes four ‘Conv1D’ blocks, a max pooling (MP) layer, a global average pooling (GAP) layer, and three fully connected (FC) layers. Every ‘Conv1D’ block is composed of a convolutional layer, a batch normalization (BN) layer, and a ReLU activation function. The global average pooling and batch normalization techniques effectively accelerate the network’s convergence speed and mitigate overfitting. Furthermore, the authors incorporated the SE attention mechanism following the initial convolutional layer to further improve the network’s feature extraction ability.

SE attention mechanism

Recently, incorporating channel attention mechanisms into CNN has gained increasing attention, significantly enhancing model performance26. Among these, the Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks have become quite popular. The SE attention mechanism substantially improves the expressive power and performance of CNN through three stages: Squeeze, Excitation, and Re-weighting27.

Squeeze phase

In the squeeze phase of the SE attention mechanism, a global average pooling process is performed on the spatial dimensions of the feature maps, compressing each channel’s feature map into a single scalar value. Let the input feature map have dimensions \(X \in \mathbb{R}^{{C \times H \times W}}\) , where \(C\) denotes the number of channels, \(H\) and \(W\) indicate the height and width of the feature map, respectively. The squeezed feature for channel \(c\) , denoted as\(z_{c}\) , is calculated as:

The aim of this stage is to gather the global information from each channel and transform it into a scalar that reflects the significance of that channel.

Excitation phase

In the excitation phase, a small feedforward neural network is applied to the global feature descriptors obtained from the squeeze phase to learn the importance weights for each channel. This network usually comprises two dense layers. The initial dense layer transforms the compressed features \(z_{c}\) to a reduced dimensionality of \(c/r\) (where \(r\) is the reduction ratio, set to 16 in this study), utilizing ReLU as the activation function. The subsequent fully connected layer then converts the output back to the original number of channels \(c\), and the sigmoid activation function is applied to obtain the excitation weights \(y_{c}\)for each channel:

where, \(W_{1}\) and \(W_{2}\) are the weight matrices of the two fully connected layers, \(\delta\) and \(\sigma\) are the activation functions applied in each layer, respectively.

Re-weighting phase

In the reweighting phase, the obtained excitation weights \(y_{c}\) are applied to each channel of the original feature map \(X\) to dynamically adjust the feature responses of each channel. Specifically, for the input feature map \(X\) , the output feature map \(X_{{SE}}\) after reweighting by the SE attention mechanism is computed as follows:

In this step, the feature map of each channel \(c\) is multiplied by its corresponding excitation weight \(y_{c}\) , thereby enhancing the feature response of important channels and reducing the influence of less significant channels.

I-Softmax loss

In multi-class classification problems, the Softmax function is commonly employed in neural networks because of its capacity to produce class probabilities and its simple mathematical formulation. However, in some cases, the use of the Softmax function does not fully meet the requirements, especially in tasks where enhancing intra-class compactness and inter-class separability is crucial. To improve feature separability and optimize performance for transfer tasks, the authors propose introducing a new loss function, namely the I-Softmax loss28, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Compared to traditional methods, the I-Softmax approach offers a flexible decision margin, In this context, the decision margin indicates the distance between the two decision boundaries. This loss function is designed to learn more discriminative feature representations, thereby achieving better performance in complex classification problems. It is defined as follows:

Compared to traditional methods, the I-Softmax approach offers a flexible decision margin,

context, the decision margin indicates the distance between the two decision boundaries. This loss function is designed to learn more discriminative feature representations, thereby achieving better performance in complex classification problems. It is defined as follows:

In this context, \(F^{i}\) represents the feature vector produced by the feature extractor. The parameters \(F^{i} \left( c \right)\) and \(F^{i} \left( j \right)\) represent the \(c\)th element corresponding to the label index and other elements, correspondingly. \(n\) represents the quantity of feature vectors, \(x \ge 0\) and \(y \ge 1\) are hyperparameters that control the decision boundaries. When \(x = 0\) and \(y = 1\) , the I-Softmax loss is comparable to the conventional Softmax loss.

To further clarify I-Softmax, the authors define the vector produced by the I-Softmax function as K, and the corresponding label vector as Z. From this, the gradient calculation formula for the loss can be expressed in the following manner:

Integrated distribution alignment framework

Due to the significant levels of random noise present in the vibration signals of rotating machinery, the gathered data roughly adheres to a Gaussian distribution and primarily consists of two estimated parameters: the mean and the variance. To further enhance the discriminative power in this domain, the authors propose combining the CORAL method with JAN to create a unified metric, termed the Integrated Distribution Alignment Framework (IDAF (A, B)).

Based on the discussion in Sect. 2.2 and Eqs. (1) and (5), we can derive the loss function for the IDAF mechanism as follows:

Additionally, note that \(\beta _{{JMMD}}\) is the coefficient used for measuring the distance with the JAN method. Finally, the gradient of the IJDA loss with respect to the network parameters can be computed via backpropagation and the chain rule, and is given by the following expression:

Conditional adversarial domain adaptation

Although the traditional DANN model performs excellently in aligning the distributions of two domains, it has certain limitations in capturing complex multimodal structures and safely conditioning the domain discriminator. To address these issues, Zhang et al.20 proposed the CDAN model, which is designed for domain adaptation and aims to solve the problem of distribution mismatch between the source and target domains \(P\left( {X_{s} ,Y_{s} } \right) \ne Q\left( {X_{t} ,Y_{t} } \right)\). Its main innovation lies in the introduction of a conditional domain discriminator, which enhances domain adaptation capability by combining features with the predictions made by the classifier. To understand the structure of CDAN, the authors define the following: Initially, let \(G_{f}\) denote the feature extractor characterized by parameters \(\delta_{f}\) , \(G_{c}\) represent the class predictor defined by parameters \(\delta _{c}\), and \(G_{d}\) indicate the domain discriminator specified by parameters \(\delta _{d}\). Additionally, a multilinear mapping operator \(\otimes\) is specified to represent the outer product of several random vectors. Therefore, the formula for the conditional adversarial loss function is as follows:

The entropy metric\(K_{{\left( p \right)}} = - \sum {_{{c = 0}}^{{c - 1}} } p_{c} \log p_{c}\) is utilized to assess the uncertainty in the predictions made by the classifier, where \(p_{c}\) represents the probability of predicting label \(c\). This entropy criterion effectively assesses the classifier’s confidence when making predictions across different labels. Additionally, an entropy-aware weighting function is introduced as follows:

This function associates the reweighting of samples with their corresponding entropy value \(K\left( p \right)\). Specifically, the higher the entropy value \(K\left( p \right)\), the smaller the weight \(w\left( {K\left( p \right)} \right)\), and vice versa. This indicates that samples with greater prediction uncertainty receive lower weights in the adjusted conditional adversarial loss function, thereby reducing their impact on the model training process. Consequently, the complete form of the conditional adversarial loss function under these conditions is as follows:

After incorporating the CDAN + E loss, the final loss is formulated as follows:

Training loss of the proposed method

The proposed method integrates three key techniques described in Sect. 3.3, 3.4, and 3.5. In Sect. 3.3, the I-Softmax loss algorithm is introduced, which, compared to the original Softmax, offers a more flexible margin, achieving higher diagnostic accuracy and learning more separable features. Section 3.4 and 3.5 elaborate on two strategies: one utilizing mapping techniques and the other employing adversarial methods. While both strategies have demonstrated some effectiveness in transfer learning, they still face certain limitations. The objective of this study is to achieve significant advancements in fault diagnosis by integrating the two methods through algorithm fusion.

Furthermore, in the mapping technique, the authors propose an innovative strategy that combines the CORAL and JAN methods. This approach systematically evaluates distribution differences from both the mean and covariance dimensions, significantly reducing the distribution discrepancies between the source and target domains. Additionally, this new method assigns different weights to CORAL and JAN, where the weight for CORAL is a fixed value, while the weight for JAN is dynamically adjusted according to a specific formula. This weight allocation mechanism facilitates effective domain adaptation and ensures an improvement in diagnostic accuracy.

In the adversarial method, the authors introduce the CDAN method, which employs an adversarial learning framework by incorporating a discriminator to distinguish between source domain and target domain data. This process facilitates the fusion of features from both domains, thereby reducing the discrepancies between them. Additionally, the method proposes conditional reflection and entropy-conditioned reflection strategies, which enhance the model’s classifier performance and transferability, respectively.

The workflow of this experiment is as follows: First, the dataset is divided into source and target domains, where the source domain contains labeled data, and the target domain consists of unlabeled data. Then, CNN is used for feature extraction, followed by pre-training. During the pre-training phase, only the I-Softmax loss function is applied to the classification task. The model focuses on optimizing classification accuracy to ensure the learning of separable features. Once the pre-training reaches a certain level of accuracy, the transfer learning process begins.

At the transfer training stage, when >, the model simultaneously performs Integrated Distribution Alignment and training with an entropy-conditioned variant of Conditional Domain-Adversarial Networks. Specifically, Integrated Distribution Alignment minimizes the distribution discrepancy between the source and target domains using the JAN and CORAL methods, while CDAN + E employs an adversarial learning framework to facilitate the fusion of features from both domains, thus reducing domain shifts and improving the performance on the target domain.

The entire training process utilizes a combined loss function, which includes I-Softmax loss, integrated distribution alignment loss, and domain adversarial loss. These loss functions are optimized through backpropagation to minimize the discrepancies between the source and target domains and improve the classification capability of the target domain. After transfer learning, the model’s performance is evaluated on the target domain to assess its diagnostic accuracy in the absence of labeled data. Ultimately, this approach effectively enables knowledge transfer between the source and target domains, significantly improving fault diagnosis accuracy. The flowchart of this process is shown in Fig. 3, and the overall training loss is defined as follows:

The simplified form of the above equation is:

Experimental validation

This study comprehensively evaluates the superior performance of a model that combines the I-Softmax loss algorithm, IDAF, and the domain-adversarial CDAN + E algorithm through experimental validation and ablation experiments on gear and bearing datasets, demonstrating the effectiveness of each module.

Dataset introduction

This study utilizes two main datasets: the Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) bearing dataset29 and the Northeast Forestry University (NEFU) gearing dataset, which are detailed as follows:

CWRU bearing dataset

The dataset from Case Western Reserve University, known as the CWRU dataset, is a well-established benchmark for diagnosing bearing faults. As depicted in Fig. 4, the experimental configuration comprises drive and loading motor, fan and drive end, a dynamometer, a torque sensor, and multiple test bearings. During the experiments, raw vibration data were captured for different fault conditions, including normal operation (NC), inner race faults (IF), ball faults (BF), and outer race faults (OF). The accelerometers recorded data at a sampling frequency of 48,000 Hz.

Data for each fault type, along with that from normal bearings, was gathered at four different speeds: 1772 r/min, 1750 r/min, 1797 r/min, and 1730 r/min. Based on these speeds, four transfer learning conditions were defined: 1797 r/min is labeled as G1, 1772 r/min as G2, 1750 r/min as G3, and 1730 r/min as G4. For the experimental validation with the CWRU bearing dataset, six transfer scenarios were selected at random. The detailed parameters for each scenario are presented in Table 2.

NEFU gear dataset

The gear dataset from Northeast Forestry University includes six fault categories: gear peeling, gear wear, gear pitting, missing teeth, normal, and gear crack30. The data was collected at a sampling frequency of 10,000 Hz under four different load conditions: 0.5 A, 1.5 A, 2.5 A, and 3.5 A. For this study, data for a load of 3.5 A was chosen, with gear speeds set at 900 rpm, 1200 rpm, and 1500 rpm. Experiments were carried out under three operational conditions, leading to six transfer scenarios: H1 for 900 rpm, H2 for 1200 rpm, and H3 for 1500 rpm. Using the NEFU gear dataset, six transfer states were established for experimental validation. Detailed parameters for these scenarios can be found in Table 3. Figure 5 illustrates the equipment used for data acquisition in the NEFU gear experiment, along with images of the various fault types.

Experimental parameter design

In this study, appropriate parameter settings were chosen for different datasets in the experimental design. For the four-class classification task on the CWRU Bearing Dataset and Jiangnan University Bearing Dataset, each class in both the source and target domains contained 1000 samples, resulting in a total of 4000 samples. For the six-class classification task on the NEFU Gear Dataset, the total number of samples was 6000. Considering the scarcity of fault samples in real-world applications, a sliding sampling technique was employed to increase the number of fault samples, ensuring that consecutive samples overlapped to capture more comprehensive features. Each sample consists of 2048 data points, with the raw vibration signals directly used as input to the model to minimize additional computational overhead.

During training, a batch size of 64 and 250 epochs were used, with an initial learning rate set to 0.000002, which was dynamically adjusted using the Step learning rate schedule with a decay factor of 0.1. Additionally, a weight decay of \(1e - 5\) was applied to prevent overfitting, and the parameters of the I-Softmax loss function were set to \(x = 16\) and \(y = 3\) to optimize the model’s classification performance. For the NEFU Gear Dataset, the learning rate was adjusted to 0.001 and the weight decay to \(1e - 4\), with the I-Softmax loss parameters set to \(x=0\) and \(y=3\). These carefully chosen and tuned parameters ensured effective knowledge transfer between the source and target domains and significantly enhanced the fault diagnosis accuracy across different tasks.

In addition, in transfer learning, the parameters of the adversarial network are consistently set to \(\alpha _{{CDAN + E}} = 1\). The JAN parameter \(\beta\) varies according to the following formula with respect to the epochs to ensure training stability and prevent imbalance:

Experimental design

Ablation study design

The authors created five experimental configurations to assess the effectiveness of each module within the model. These experiments showcase the best module selections and emphasize the innovative features of the proposed approach, especially in terms of network architecture design and loss function development. Specifically, the study conducted validation using the G3→G1 transfer scenario on the CWRU bearing dataset and the H3→H1 transfer scenario on the NEFU gear dataset. These transfer scenarios were chosen due to their generally low accuracy rates across various methods, allowing for a clearer comparison of the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches. It should be noted that in the I-Softmax method, the “×” symbol does not indicate a complete absence of activation functions but rather signifies the replacement of I-Softmax with the traditional Softmax method. Tables 4 and 5 present the detailed experimental results and parameter configurations.

To better illustrate the superiority of the proposed method, the authors compared the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score results from each group of ablation experiments. The comparison is depicted in Fig. 6, with Figure (a) showing the results for the CWRU bearing dataset and Figure (b) presenting the results for the NEFU gear dataset. These figures clearly highlight the performance of various methods based on the evaluated metrics, further supporting the advantages of the proposed approach.

Comparative experimental design

To further confirm the effectiveness and advantages of the proposed IADTLN network, the authors conducted a comparison with ten established transfer learning methods. Note that these methods use traditional, unmodified network architectures. These include Method 1, based on CORAL; Method 2, utilizing MK-MMD; Method 3, employing JMMD, all of which are prominent distance metric-based data analysis models; Method 4, based on DANN; Method 5, using CDAN; Method 6, incorporating CDAN + E, which represent data analysis models based on adversarial mechanisms; Method 7, a combined approach integrating JMMD and CDAN + E31; Method 8, which uses DDTLN28; Method 9, the Adaptive Batch Normalization and Combined Optimization Method32; and Method 10, using VDR33.

To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy and robustness of the IADTLN framework, six cross-machine transfer tasks were conducted using both the CWRU bearing dataset and the NEFU gear dataset. To ensure reliability, each method was run five times for every transfer task. The average diagnostic accuracies for the eight methods are presented in Tables 6 and 7.

Experimental analysis

In the CWRU bearing dataset, as illustrated in Table 6, our proposed approach demonstrates superior performance in the most difficult transfer task, G3→G1, achieving an accuracy of 94.64%, which significantly surpasses other conventional transfer learning frameworks. Additionally, the accuracy rates for G1→G2, G1→G4, G2→G4, G3→G2, and G4→G3 all exceed 95%, indicating strong robustness of our method. Fig 0.7 presents the confusion matrix of our method, clearly illustrating the misclassification of each category in the tasks. Furthermore, Fig 0.8 presents a visual depiction of the classification outcomes using clustering plots.

To further evaluate the efficacy of the proposed method, the author carried out experiments on the more challenging NEFU gear dataset. As demonstrated in Table 7, our method attained the highest accuracy in all transfer tasks. Notably, in the H3→H1 task, other transfer methods exhibited significantly lower accuracy. Fig 0.9 and Fig 0.10 display the confusion matrices and clustering plots, respectively, providing a clear depiction of our method’s classification performance across different tasks. Pre-training for the first 50 epochs was used as a baseline, even without employing any transfer learning methods, which still achieved some level of accuracy. However, as observed in Table 7, methods 1, 2, 5, and 6 experienced negative transfer in tasks H3→H1 and H3→H2 (where the accuracy with transfer methods was lower than with the baseline pre-training), leading to extremely low experimental precision34. Therefore, our method demonstrates higher accuracy when faced with complex transfer tasks, fully reflecting its advantages and practicality.

Further experimental study

To further validate the effectiveness of the IADTLN model in cross-speed and cross-fault mode transfer learning, as well as to explore its adaptability across different datasets, this study conducts experiments using the Jiangnan University (JNU) bearing dataset. The dataset has a sampling frequency of 50,000 Hz and contains bearing fault signal data under various operating conditions. Two types of rolling bearings were selected for the experiment: N205 and NU205. The N205 bearing covers three fault conditions: normal, outer race defect (OF), and ball fault (BF), while the NU205 bearing focuses on inner race defects (IF). All fault data were generated using a wire-cutting robot and collected under three different rotational speeds: 600 r/min, 800 r/min, and 1000 r/min.

The primary goal of this study is to investigate the transfer learning capability of the IADTLN model under different rotational speed conditions. To achieve this, six transfer learning tasks based on speed were designed, where 600 r/min, 800 r/min, and 1000 r/min are labeled as J1, J2, and J3, respectively. The transfer tasks include: J1 → J2, J1 → J3, J2 → J1, J2 → J3, J3 → J1, and J3 → J2. These tasks are designed to evaluate the cross-domain transfer learning performance of the IADTLN model under different rotational speeds.

Since the IADTLN model has already demonstrated clear advantages over traditional diagnostic methods in previous experiments, this study focuses only on comparing it with the latest models in the fault diagnosis field to highlight its superiority. The experimental results, as shown in Table 8, demonstrate that the IADTLN model consistently outperforms other diagnostic models, with an average diagnostic accuracy exceeding 96%. These results further confirm the strong generalization ability of the IADTLN model in cross-device fault diagnosis and provide additional evidence that its transfer learning capability across different speeds and fault modes is superior to other existing diagnostic models.

Conclusion

This study proposes a novel method that integrates SE attention mechanism, discriminative feature learning, and a combination of Integrated Distribution Alignment Framework and Conditional Domain Adversarial Network with Entropy losses. The SE attention mechanism is employed to perform channel-wise weighting on the extracted features, enhancing useful features while suppressing redundant ones, thus reducing the interference from irrelevant or noisy factors. Next, the I-Softmax loss function is applied to enhance the learning of more distinctive fault features, thereby increasing diagnostic accuracy. In terms of domain adaptation, the authors utilize joint feature mapping and adversarial networks, employing IDAF and CDAN + E losses to achieve domain alignment and reduce domain shift. The experimental findings indicate that this method yields substantial performance enhancements on both the bearing and gear datasets, confirming its effectiveness and robustness.

Despite the reliance on vibration signal data in this study, which poses certain limitations, future efforts will concentrate on combining various types of sensor data, including vibration, sound, and temperature, to achieve more comprehensive and accurate fault diagnosis. Future research will explore how to effectively fuse multimodal data and leverage their interrelationships to further improve fault detection and diagnostic capabilities.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Li, Q. et al. Deep expert network: A unified method toward knowledge-informed fault diagnosis via fully interpretable neuro-symbolic AI[J]. J. Manuf. Syst. 77, 652–661 (2024).

Naveen, G. J. et al. Analyzing gear blank failure: A comprehensive industrial case Study[J]. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 24 (1), 83–96 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Mixed Style Network Based: A Novel Rotating Machinery Fault Diagnosis Method Through Batch Spectral Penalization[J]110667 (Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 2024).

Amanullah, M. A. et al. Deep learning and big data technologies for IoT security[J]. Comput. Commun. 151, 495–517 (2020).

Dong, S., Wang, P. & Abbas, K. A survey on deep learning and its applications[J]. Comput. Sci. Rev. 40, 100379 (2021).

Gonzalez-Jimenez, D. et al. Data-driven fault diagnosis for electric drives: A review[J]. Sensors 21 (12), 4024 (2021).

Patil, D. et al. Machine learning and deep learning: methods, techniques, applications, challenges, and future research opportunities[J]. Trustworthy Artif. Intell. Ind. Soc., : 28–81. (2024).

Li, Q. et al. Transparent Operator Network: a Fully Interpretable Network Incorporating Learnable Wavelet Operator for Intelligent Fault diagnosis[J] (IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 2024).

Kim, S., Kim, I. & You, D. Multi-condition multi-objective optimization using deep reinforcement learning[J]. J. Comput. Phys. 462, 111263 (2022).

Li, B. et al. A novel semi-supervised data-driven method for chiller fault diagnosis with unlabeled data[J]. Appl. Energy. 285, 116459 (2021).

Li, X., Li, X. & Ma, H. Deep representation clustering-based fault diagnosis method with unsupervised data applied to rotating machinery[J]. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 143, 106825 (2020).

Udmale, S. S. et al. Multi-fault bearing classification using sensors and ConvNet-based transfer learning approach[J]. IEEE Sens. J. 20 (3), 1433–1444 (2019).

Singh, R. et al. Identifying tiny faces in thermal images using transfer learning[J]. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 11, 1957–1966 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Multiscale ECA network: a rotation mechanical domain adaptation method with minimal class confusion[J]. Struct. Health Monit., : 14759217241261155. (2024).

Li, Y. et al. State-of-health Estimation of lithium-ion batteries based on semi-supervised transfer component analysis[J]. Appl. Energy. 277, 115504 (2020).

Jia, S. et al. Joint distribution adaptation with diverse feature aggregation: A new transfer learning framework for bearing diagnosis across different machines[J]. Measurement 187, 110332 (2022).

Jiang, L. et al. A deep Convolution Multi-Adversarial adaptation network with correlation alignment for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery under different working conditions[J]. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 126, 107179 (2023).

Goodfellow, I. et al. Generative adversarial networks[J]. Commun. ACM. 63 (11), 139–144 (2020).

Sicilia, A., Zhao, X. & Hwang, S. J. Domain adversarial neural networks for domain generalization: when it works and how to improve[J]. Mach. Learn. 112 (7), 2685–2721 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. EMG-based cross-subject Silent Speech Recognition Using Conditional Domain Adversarial network[J] (IEEE Transactions on Cognitive and Developmental Systems, 2023).

Wang, T. & Lin, Y. CycleGAN with better cycles[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.15374, (2024).

Wang, Q. et al. A comprehensive survey of loss functions in machine learning[J]. Annals Data Sci., : 1–26. (2020).

Li, J. et al. Frequency-aware discriminative feature learning supervised by single-center loss for face forgery detection[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. : 6458–6467. (2021).

Cho, J. W. et al. Mcdal: maximum classifier discrepancy for active learning[J]. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learn. Syst. 34 (11), 8753–8763 (2022).

Xie, X. et al. Oriented R-CNN for object detection[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision. : 3520–3529. (2021).

Li, X. et al. A fault diagnosis method with AT-ICNN based on a hybrid attention mechanism and improved convolutional layers[J]. Appl. Acoust. 225, 110191 (2024).

Nath, A. G. et al. Structural rotor fault diagnosis using attention-based sensor fusion and transformers[J]. IEEE Sens. J. 22 (1), 707–719 (2021).

Qian, Q. et al. Deep discriminative transfer learning network for cross-machine fault diagnosis[J]. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 186, 109884 (2023).

Neupane, D. & Seok, J. Bearing fault detection and diagnosis using case Western reserve university dataset with deep learning approaches: A review[J]. Ieee Access. 8, 93155–93178 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Gear pitting fault diagnosis with mixed operating conditions based on adaptive 1D separable Convolution with residual connection[J]. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 142, 106740 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Fusing joint distribution and adversarial networks: A new transfer learning method for intelligent fault diagnosis[J]. Appl. Acoust. 216, 109767 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Transfer learning for bearing fault diagnosis: adaptive batch normalization and combined optimization method[J]. Meas. Sci. Technol. 35 (4), 046106 (2024).

Qian, Q. et al. Variance discrepancy representation: A vibration characteristic-guided distribution alignment metric for fault transfer diagnosis[J]. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 217, 111544 (2024).

Minoofam, S. A. H., Bastanfard, A. & Keyvanpour, M. R. TRCLA: a transfer learning approach to reduce negative transfer for cellular learning automata[J]. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learn. Syst. 34 (5), 2480–2489 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2572022BF07), in part by the Northeast Forestry University College Students’ Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (202410225289), in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant (52161135101), and in part by the Harbin Science and Technology Innovation Talent Project (2023HBRCCG004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors’ ContributionsYuxuan Yang: Responsible for the conception, design, development, and implementation of the new method, as well as conducting experimental validation and writing the initial draft of the manuscript.Jiarui Jing: Involved in the development of the code for the paper.Jian Zhang: Responsible for the collection and preprocessing of vibration signal data, assisting with the design of the experimental setup, providing critical input on the interpretation of experimental results, and participating in the writing and editing of the manuscript.Ziyu Liu: Involved in project management, ensuring coordination among various components, and assisting with the final revision of the manuscript.Xueyi Li: Provided significant insights into multimodal data integration and future research directions, participated in formulating the future work plan, and assisted in writing the conclusion and future work sections of the manuscript.All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript, ensuring the accuracy and integrity of the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Jing, J., Zhang, J. et al. Discriminative fault diagnosis transfer learning network under joint mechanism. Sci Rep 15, 8888 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93996-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93996-1