Abstract

To translate, cross-culturally adapt, and evaluate the psychometric properties of the Cystic Fibrosis (CF) Stigma Scale. This exploratory methodological study involved the translation and cross-cultural adaptation using the translation, back-translation, review by experts committee, and pre-test steps. The psychometric properties were analyzed by applying the adapted instrument to a sample of 52 Brazilian individuals with CF over 18 years old. Moreover, the participants responded to the Short-Form 12-Item Survey - version 2 (SF-12v2), General Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) and Cystic Fibrosis Quality of Life Questionnaire - Revised (CFQ-R). The content validity, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity were also assessed. The translation and cross-cultural adaptation obtained Cohen’s kappa coefficients > 0.61 in the experts committee step and ranged between 0.48 and 0.72 in the pre-test. The Brazilian version of the CF Stigma Scale showed excellent psychometric properties, observed by the internal consistency (α = 0.836), mean correlation between items (0.3) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.886; p < 0.0001), and convergent validity (positive correlation with the anxiety scale and negative correlation with scores of overall and specific quality of life for CF). The Brazilian version of the CF Stigma Scale was accurately translated and cross-culturally adapted, with favorable psychometric properties for future studies involving the stigma experience in Brazilian individuals with CF over 18 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal-recessive genetic disease which affects the function of various organs in a person. It is the most common life-threatening, inherited disease in caucasian and is caused by mutations in the gene encoding for the CF transmembrane conductance regulator1. Technological advancements improved the treatment of individuals with cystic fibrosis and increased their life expectancy, currently estimated at 50 years2. However, information on how adolescents and young adults cope with CF are limited3.

The productive cough, repetitive lung infections, and high number of hospitalizations associated with CF may cause a negative perception of health in individuals without CF who are unfamiliar with coping with this reality4,5,6. These factors, combined with premature mortality, physical impact, and low social acceptance of symptoms, may stigmatize individuals with CF7.

The word “stigma” defines any situation in which an individual is not fully accepted by others, with depreciation and distinction regarding a particular social level8. Also, health-related stigma occurs when the negative social experience or judgments are based on a health condition, resulting in social rejection, guilt, or devaluation9. Individuals with CF experience stigma since childhood, at home (due to physical differences from siblings caused by malnutrition) and school (due to the frequent cough and easy tiredness compared with their peers). Additionally, changes in the daily routine occur due to symptoms and the treatment needed, and these differences may lead to fear of non-acceptance and induce anxiety and concern in social interactions10.

Social withdrawal may lead to emotional disturbances, such as low self-esteem, helplessness, and depression11. Also, psychosocial issues were associated with changes in lung function in individuals with CF12. Moreover, the stigma may impair treatment adherence since the need to feel similar to healthy individuals may lead to a lack of commitment to the clinical routine. In other cases, individuals with CF hide the diagnosis from their social circle, concealing the symptoms and taking medication covertly11.

Despite the importance, few studies and instruments address the stigma in CF. In 2014, Pakhale et al.13 proposed the CF Stigma Scale to assess stigma in CF based on a scale for individuals with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. The authors found positive correlations with other questionnaires for anxiety, depression, and symptom severity and a negative correlation with the quality of life score14.

In Brazil, a lack of instruments assessing the stigma experienced by individuals with CF is observed. Therefore, this study aimed to translate, cross-culturally adapt, and evaluate the psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the CF Stigma Scale.

Methods

This exploratory methodological study was conducted between August 2018 and April 2020 and included the participation of translators, experts, individuals with CF, and their caregivers. Figure 1 illustrates the study flowchart.

The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte and followed the Declaration of Helsinki and Resolution 466/12 of the Brazilian National Health Council (no. 96606918.3.0000.5537).

All individuals were informed about the aims, justification, risks, benefits, and procedures of the study, considering its methodology. They were also informed about the voluntary nature of participation, preservation of the anonymity of the recorded data, and the possibility of refusing to participate or drop out at any time without prejudice. After explanations, all individuals signed the informed consent form.

The CF Stigma Scale developed by Pakhale et al.13 consists of 10 items, which address different dimensions of stigma, such as shame, discrimination, and the social impact of the disease. Each item is evaluated using a Likert scale, allowing the measurement of the participants’ degree of agreement or disagreement with statements about their experience of stigma. The CF Stigma Scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity, correlating with instruments that assess quality of life, anxiety, depression, and symptom severity. For this study, the original version of the scale was translated and culturally adapted to the Brazilian context, with the aim of evaluating its applicability and psychometric properties in a sample of Brazilian patients with CF.

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation

Initially, authorization and collaboration were requested from the authors of the original CF Stigma Scale. Respecting copyright laws, Dr. Smita Pakhale (the main author) agreed and made herself available to assist in the steps.

The methodological procedure followed the models Guillemin et al.15 and Beaton et al.16, as well as the recommendations of the Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments17 and Mapi Research Institute18. The models comprise the following steps: translation; synthesis of translations; back-translation and synthesis of back-translations; review by a multiprofessional experts committee (MEC) using the Delphi method19,20; pre-test21. The last two steps were assessed using the Cohen’s kappa coefficient, according to the indices proposed by Landis and Koch22.

Two independent Brazilian translators fluent in English translated the original scale into Brazilian Portuguese. One translator was an expert in the field, familiar with the aim of the scale, and translated considering a clinical and technical perspective. The other was a non-expert, without knowledge of the scale, and represented the popular language.

A review committee (i.e., the two translators and responsible researchers) developed a consensus version of the two translations and a report with modifications and adjustments. The report and translation were sent to the authors of the original scale for analysis.

The consensus version was back translated into English to verify the content correspondence. In this step, two independent bilingual translators (native English speakers and proficient in Portuguese) with no prior contact with the scale and its aim translated the Brazilian version into English.

A new review committee (i.e., the main researcher and back-translators) developed a consensus version of the back-translations and sent it to the original authors with the report of this step. After approval, a Brazilian Portuguese professor verified the adequacy of the items of the Brazilian version to the language norms.

Cross-cultural equivalence is accomplished when the items of an instrument maintain the content validity for application in various cultural conditions16. Thus, the expert panel method was used19, comprising a MEC with eight professionals: two pulmonologists; two physical therapists; one psychologist researcher experienced in cross-cultural adaptation and one not directly involved with CF; and one mother of individual with CF and one individual with CF above 18 years16. Each pair of professionals was formed considering that one had direct involvement with CF and the other did not.

The MEC received the original scale, all versions of the translations, and reports and ensured the semantic, idiomatic, and contextual equivalences between the translation and original version15. Semantic equivalence determines multiple meanings for an item and grammatical difficulties in translation, the idiomatic verifies whether colloquial words are difficult to understand or translate, and the contextual analyzes the possibility of different meanings of words in different cultures.

Equivalences were analyzed using the Delphi method through a virtual form (Google Forms®) individually and confidentially sent via email20. The concordance was evaluated using a dichotomous scale, in which (0) indicated complete disagreement and (1) indicated complete agreement19. Each member of the MEC scored and justified the items of the Brazilian version for clarity, concordance, and adequacy to the cultural context. The approval of the items followed the scores and agreement between experts.

The acceptable validity content is not standardized due to the subjective judgment. However, this studies subjectivity can be reduced by using Cohen’s kappa coefficient21, and agreement values proposed by Landis and Koch22. After review and consensus by the MEC, the instrument was sent to the original authors for analysis.

The pre-final version was conducted online with 30 Brazilian individuals over 18 years old diagnosed with CF by the sweat test16,21, selected using non-probability (convenience) sampling. Those unable to perform or understand the procedures or who underwent lung transplantation were excluded. Individuals were recruited through disclosure on the social media of the Unidos Pela Vida institution, aimed at professionals, parents, family members, and individuals with CF. Individuals responded to the translated version and a dichotomous scale regarding their understanding of each item using Google Forms®, which was analyzed using Cohen’s kappa21,22. Last, the Brazilian version of the CF Stigma Scale was sent to the original authors for final approval of the methodological process.

Analysis of psychometric properties

After the cross-cultural adaptation, the psychometric properties of the Brazilian CF Stigma Scale were analyzed according to the methodological design of the original study by Pakhale et al.13. The sample consisted of Brazilian individuals over 18 years old diagnosed with CF by the sweat test, selected using non-probability (convenience) sampling. Individuals unable to perform or understand the procedures or with lung transplantation were excluded.

Although methodological validation studies have no specific sample size calculation, five to ten individuals are recommended for each item, resulting in a sample of 50 individuals since the scale has 10 items23. According to data from the Brazilian CF Registry, in 2020, there were a total of 6,112 individuals with CF. In Brazil, the CF population is predominantly pediatric and the proportion of adults is still less than 30% of the total. Thus, a sample of 50 individuals corresponds to almost 3% of the adult population24.

Individuals were recruited through dissemination on the social media of the Unidos Pela Vida institution, aimed at professionals, parents, family members, and individuals with CF. Those interested contacted the researchers and received a link for the Google Forms® with the informed consent and study forms. The individuals with CF included in the translation and cross-cultural adaptation phase also participated in this analysis.

Initially, individuals responded to the test step regarding personal and socioeconomic data. Next, four instruments were presented: Short-Form 12-Item Survey - version 2 (SF-12v2), General Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7), Cystic Fibrosis Quality of Life Questionnaire - Revised (CFQ-R), and the Brazilian CF Stigma Scale. The retest step was conducted after three weeks, when individuals responded to the same instruments. The test-retest period in the original study was three months. Since the study was conducted during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, we shortened the test-retest period of the present study to minimize potential sample losses.

The SF-12v2 is a self-report scale assessing the general quality of life, with 12 items to assess the current physical and mental health status of individuals based on their experiences over the past four weeks. It is a short version of the Short-Form 36-Item to reduce the time completion without compromising the quality of assessment. Responses are recorded on a five-point scale ranging from “all the time” to “never” or “excellent” to “poor”; a cut-off score of 50 points determines a good quality of life25.

The GAD-7 is a self-report scale of seven items assessing anxiety over the past two weeks. Each item addresses a symptom of anxiety grouped into a single domain for generalized anxiety. Responses are recorded on a four-point scale (0 = not at all; 1 = several days; 2 = more than half the days; 3 = nearly every day), and the total score ranges from 0 to 21; high scores correspond to greater severity of anxiety symptoms. Moreno et al.26 translated and validated the GAD-7 for the Brazilian population.

The CFQ-R is a self-report scale for individuals ≥ 14 years old composed of 50 questions grouped into physical, role, vitality, emotion, social, nutrition, body image, treatment, health, weight, respiratory, and digestive domains. Scores for each domain range from 0 to 100, and a 50-point cut-off indicates a good quality of life27. The CFQ-R was translated and validated into Brazilian Portuguese by Rozov et al.28.

Analysis

Data were exported to an Excel spreadsheet to verify missing values and to the SPSS version 26 for analysis. Data were presented as mean and standard deviation, with a significance level of 5%. The content validity, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity were assessed. The test-retest interval was three weeks. Also, internal consistency (Cronbach alpha coefficient) and test-retest reliability (Pearson correlation coefficient) were considered as reliability for the total score and subscales. The convergent validity was calculated using the paired t-test.

Results

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation

Adjustments during the translation and cross-cultural adaptation prevented potential misunderstanding due a literal translation. In item 4, the word “bad” would have a literal translation of “ruim” and was changed to “má” to maintain the real meaning. In item 5, the word “disgusting” is translated as “repugnante”, which is not commonly used in colloquial language and could also misrepresent the real meaning, being consensually changed to “desagradável”. Also, sentence sequences in other items were slightly changed to be better understood by Brazilian individuals with CF.

After analysis by the MEC, Cohen’s kappa coefficients were > 0.61, indicating substantial concordance and dismissing new discussions22. In the pre-test, 30 individuals with CF aged between 18 and 42 years were included, being 22 (73%) females. The education level varied from incomplete high school to higher education. Cohen’s kappa coefficient for clarity and understanding of the items ranged from 0.48 to 0.72, indicating moderate to substantial concordance22.

Analysis of psychometric properties

A total of 60 individuals with CF were interested in the study, of which 57 and 52 completed the test and retest, respectively. Only data from individuals who completed both steps were used for the analysis of psychometric properties. Table 1 shows the sample characterization.

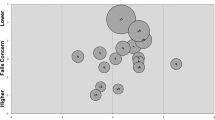

The analysis of psychometric properties and reliability measures are presented in Table 2. The Brazilian CF Stigma Scale scores positively correlated with GAD-7 and negatively with SF-12v2 scores. The Brazilian CF Stigma Scale also demonstrated adequate internal consistency (α = 0.836), strong test-retest correlation (r = 0.886, p < 0.0001), and no significant difference between items responses in the test and retest (p = 0.3).

Table 3 shows the correlation of the Brazilian CF Stigma Scale scores with SF-12v2 and CFQ-R domains. The Brazilian CF Stigma Scale was negatively correlated with the mental domain of the SF-12v2 and domains physical, role, vitality, emotion, social, body image, treatment, and health of the CFQ-R.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that the Brazilian CF Stigma Scale was adequately adapted and cross-culturally validated, with substantial content validity, high level of internal consistency, convergent validity (moderate and significant correlations with the other instruments), and strong test-retest reliability. These results corroborated those found by Pakhale et al.13. The profile of translators and inclusion of individuals with or related to CF in the MEC may have provided robustness to the translation and cross-cultural adaptation, favoring the semantic, conceptual, and contextual equivalences29,30,31,32,33.

Psychometric properties demonstrated that the Brazilian CF Stigma Scale may be used nationwide since it can provide valid and reliable information about the experience of stigma. When compared with the SF-12v2 and CFQ-R domains, the Brazilian CF Stigma Scale scores showed moderate negative correlations with mental (SF-12v2), motion, and health (CFQ-R) domains, and a strong negative correlation with the social domain (CFQ-R), whereas the other correlations were not significant. These results suggested that mental state, emotions, health, and especially social interactions could influence the perception of stigma.

The selection of a non-probabilistic sample should be considered when interpreting our results. However, this fact does not undermine the contribution of this study, which is the translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the CF Stigma Scale for Brazilian individuals with CF. Moreover, despite being large, the sample did not comprise individuals from diverse Brazilian regions, socioeconomic classes, and educational levels. However, once the Brazilian CF Stigma Scale is validated for the national territory, professionals may use it to assess whether individuals with CF from different regions and specific contexts are experiencing any stigma. Moreover, this scale may be compared with other instruments assessing factors that may trigger stigma and impact treatment adherence, as hypothesized by Berge and Patterson11.

Considering that data for the analysis of psychometric properties were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, social isolation may have influenced the scores of the instruments included in the study since they assess quality of life and anxiety. However, this influence possibly did not affect the validation and evaluation of psychometric properties since individuals were already in social isolation during data collection in the first step. Another limitation of the study was the exclusion of some instruments used by Pakhale et al.13. For example, the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale could not be used because its Brazilian Portuguese translation was not accessible.

Although the test-retest period of the present study (three weeks) was shorter than in the original study (three months), results were possibly not affected. The GAD-7 and CFQ-R responses refer to the last two weeks, while SF-12v2 is based on the experiences over the past four weeks. Considering the CF Stigma Scale, the stigma associated with chronic respiratory diseases typically does not have an acute onset; it tends to develop gradually over time. Stigma intensifies as symptoms become more evident and the limitations imposed by the condition become notable to others. Therefore, stigma is more often a phenomenon that builds over time rather than arising suddenly. Thus, the experience of stigma is unlikely to change over three weeks.

In conclusion, the CF Stigma Scale was translated and adapted for the Brazilian context and demonstrated favorable psychometric properties for use in the Brazilian population. It is easy to apply and cost-effective and should be used in future studies to assess whether the experience of stigma is present in different socioeconomic and educational contexts or in younger individuals. Also, further studies should explore potential relationships between the Brazilian CF Stigma Scale and respiratory (e.g., lung function) or health-related outcomes (e.g., treatment adherence).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Lima TRL, Guimarães FS, Ferreira AS, Penafortes JT, Almeida VP, Lopes AJ. Correlation between posture, balance control, and peripheral muscle function in adults with cystic fibrosis. Physiotherapy Teoric and Practice 2013;30(2):79–84.

Dodge JA et al: Cystic fibrosis mortality and survival in the UK: 1947–2003. European Respiratory Journal 2007, 29(3):522–526.

Oliver KN. et al: Stigma and optimism in adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2014, 13, 6:737–744.

Ferrin M, Cianci K, Finnerty M, McDonald G, Smith T, Thrasher S: Cystic Fibrosis in the Workplace. the Questions, the Needs, the Solutions. Bethesda, MD: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; 2003.

Cystic Fibrosis Canada: Insurance with people with Cystic Fibrosis. Toronto, ON, Canada: 2013.

Ernst MM, Johnson MC, Stark LJ: Developmental and psychosocial issues in CF. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2010, 19:263.

Bok C: Relationships of Health Behaviours with Stigma and Quality of Life among Adolescent and Young Adults with Cystic Fibrosis. OH: Ohio State University; 2011.

Goffman E. Estigma: Notas Sobre a Manipulação Da Identidade Deteriorada. 4º ed. Rio de Janeiro: LTC; 1988.

Lebel S, Devins GM: Stigma in cancer patients whose behavior May have contributed to their disease. Future Oncol 2008, 4(5):717–73.

Pizzignacco TMP, de Mello DF, de Lima RAG: Stigma and cystic fibrosis. Revista latino-americana De Enfermagem 2010, 18(1):139–142.

Berge JM, Patterson J: Cystic fibrosis and the family: a review and critique of the literature. Fam Syst Health 2004, 22:74–100.

Steinhausen HC, Schindler HP: Psychosocial adaptation in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1981, 2:74–77.

Pakhale S et al: Assessment of stigma in patients with cystic fibrosis. BMC Pulmonary Medicine 2014,14(1): 76.

Wright K, Naar-King S, Lam P, Templin T, Frey M: Stigma scale revised: reliability and validity of a brief measure of stigma for HIV + youth. J Adolesc Health 2007, 40:96–98.

Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993, 46(12):1417–32.

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 25(24):3186–91.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2010, 63(7):737–45.

Acquadro C, Conway K, Wolf B, Hareendran A, Mear I, Anfray C, et al. Development of a standardized classification system for the translation of Patient- reported outcome (PRO) measures brief measure of psychological Well-Being. Patient Rep Outcomes. 2008, 39:5–7.

Pinheiro JQ, Farias TM, Abe-lima JY: Painel de especialistas e estratégia Multimétodos: Reflexões, Exemplos, Perspectivas. Psico 2013, 44(2):184–92.

Powell C: The Delphi technique: Myths and realities. Methodol Issues Nurs Res. 2003, 41(4):376–82.

Reichenheim ME, Moraes CL. Operacionalização de Adaptação transcultural de instrumentos de Aferição Usados Em epidemiologia. Rev Saude Publica. 2007, 41(4):665–73.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977, 33(1):159–74.

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Thalam RL. Análise multivariada de Dados. Porto Alegre: Bookman 2005:593.

Grupo Brasileiro de Estudos de Fibrose Cística. Registro Brasileiro de Fibrose Cística ano 2020 [Internet]. Available from: https://portalgbefc.org.br/ckfinder/userfiles/files/REBRAFC_2020.pdf

Damásio BF, Andrade TF, Koller SH: Psychometric properties of the Brazilian 12-Item Short-Form health survey version 2 (SF-12v2). Paidéia 2015: 29–37.

Moreno AL et al: Factor structure, reliability, and item parameters of the Brazilian-Portuguese version of the GAD-7 questionnaire. Temas Em Psicologia 2016, 24(1): 367–376.

Cohen MA, Ribeiro MA, Ribeiro AF, Ribeiro JD, Morcillo AM. Quality of life assessment in patients with cystic fibrosis by means of the cystic fibrosis questionnaire. J Bras Pneumol. 2011;37(2):184–92.

Rozov T. et al: Linguistic validation of cystic fibrosis quality of life questionnaires. Jornal De Pediatria 2006, 82(2):151–156.

Ramada-Rodilla JM, Serra-Pujadas C, Delclós-Clanchet GL. Crosscultural adaptation and health questionnaires validation: revisionand methodological recommendations [Article in Spanish]. SaludPublica Mex. 2013;55(1):57–66.

Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(2):268–74.

Victal ML, Lopes MH, D’Ancona CA. Adaptation of the O’Leary-Sant and the PUF for the diagnosis of interstitial cystitis for the Brazilian culture [Article in Portuguese]. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2013;47(2):312–9.

Jensen R, Cruz Dde A, Tesoro MG, Lopes MH. Translation and cultural adaptation for Brazil of the developing nurses’ thinking model. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2014;22(2):197–203.

Oliveira VHB, de Mendonça KMPP, Alchieri JC, Pakhale S, Balfour L, dos Santos WHB, Nogueira PADMS. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and evaluation of psychometric properties of cystic fibrosis stigma scale. Research Square. 2022.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Provatis Academic for providing scientific language translation and revision. The authors acknowledge the technical and administrative support of the Research Square team for providing the opportunity to present our manuscript on their platform, which allowed for greater visibility and pre-publication discussion of our work. This work is supported by the Laboratory of measures and evaluation in health, Program in Physical Therapy, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (N°. PVD15211-2018). This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: VHBdO, TRAO, ISdS, JCA, SP, IDBN, PAdMSN. Methodology: VHBdO, JCA, SP, IDBN, PAdMSN.Writing – original draft: VHBdO, TRAO, ISdS.Writing – review & editing: VHBdO, TRAO, ISdS, JCA, SP, IDBN, PAdMSN.All authors contributed to editing the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Oliveira¹, V.H.B., Oliveira, T.R.A., da Silva, I.S. et al. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and evaluation of psychometric properties of the cystic fibrosis stigma scale. Sci Rep 15, 15789 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94171-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94171-2