Abstract

The Yushenfu mining area has special hosting conditions, and the high-intensity coal mining is likely to cause surface cracks and negative impacts on the ecological environment. To accurately predict the location and depth of surface cracks, this paper proposed a prediction method that uses horizontal deformation as the key parameter, incorporating the stress-deformation characteristics of the loose layer. In this paper, the Yushenfu mining area was selected as the study area, the prediction formula of horizontal deformation was optimized and the Active Phase of the subsidence process was classified into two stages. A mechanical model of the wedge-shaped loose layer was established, combining this with the mechanical properties of the surface loose layer in Yushenfu mining area, a prediction method for the location and depth of surface crack was provided. Using the 112201 working face as a case study, the influence of seasonal rainfall on soil strength properties was considered. The results demonstrate that the optimized horizontal deformation formula has better performance compared with traditional calculations, and the accuracy of the method was verified and validated through on-site observations. The research provides an effective approach for predicting the location and depth of mining-induced surface cracks in the Yushenfu mining area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Yushenfu mining area, situated at the junction of the Mu Us Desert and the Loess Plateau, serves as a strategic coal production base underpinning China’s energy security. This ecologically vulnerable region exhibits surface geology dominated by alternating loess and aeolian sand layers, coupled with severe water scarcity and delicate surface ecosystems. Large-scale coal mining activities have triggered multiple geological hazards, with surface cracks emerging as the most severe environmental challenge1. These mining-induced cracks disrupt fragile ecosystems by accelerating water loss and topsoil degradation, while also posing risks to local communities. Therefore, it is urgent to study the formation mechanisms of surface cracks and developing effective prediction methods.

Mining-induced surface cracks constitute a progressive geomechanical phenomenon resulting from stress redistribution and overburden structural failure during coal extraction2. Some mining experts and scholars have carried out a series of research on the key parameters influencing surface cracks, such as mining condition, key strata movement, topography, and the rate and acceleration of subsidence3,4,5,6,7,8. In response to the unique topography of the western loess area, scholars have studied and classified mining-induced cracks, methods such as dynamic monitoring and numerical simulations were employed to study the static and dynamic evolution laws9,10,11. Yan et al.12 found that cracks tend to appear when tensile deformation values exceed 2–3 mm/m. Zhou et al.13 and Hu et al.14 conducted field surveys and analyses in aeolian sand-covered areas, revealing the relationship between the "M-shaped" activity of surface cracks and deformation. Hou et al.15 conducted field surveys on typical mines in Yushenfu mining area, studying the dynamic and static development laws of surface cracks, and revealing the mechanisms of crack activity in different locations.

Many scholars have also discussed the development laws of cracks from the perspectives of stress and deformation. Liu et al.16 discovered that surface cracks often develop in the surface tension zone ahead of the working face. Huang et al.17 and Cao et al.18 proposed that surface cracks are tension fissures developed from top to bottom due to subsidence effects. Yu et al.19 and Wang et al.20 suggested that when the tensile stress exerted on soil exceeded its ultimate tensile strength, it causes tensile-type surface cracks. Cao et al.21 combined fracture mechanics and soil mechanics to analyze the cracking mechanism of surface cracks from a microscopic perspective. Tang et al.22 and Xu et al.23 established a dual-probability integral prediction model for surface deformation and preliminarily derived a theoretical calculation formula for the development range of surface cracks. Wu et al.24studied the relationship between stress distribution in soils and the expansion of crack development and proposed a predictive model for the maximum development depth of soil cracks. The formation of mining-induced surface cracks is the result of combined internal and external factors, where horizontal deformation caused by mining is the primary external factor10,25, and the strength characteristics of the soil itself are the main internal factor26.

Accurate prediction of horizontal deformation is essential for determining the development morphology of cracks. Currently, the accuracy of subsidence deformation prediction models is typically enhanced by combining the Knothe time function27,28,29,30. Huang et al.31 refined the three stages of surface movement and Chang et al.32 addressed the issue of low accuracy in the Initial Phase of subsidence deformation prediction models.

As described above, many experts have studied the causes and development laws of surface cracks and have proposed theoretical prediction methods for crack development morphology. However, the Yushenfu mining area has unique environmental conditions and high mining intensity, with surfaces predominantly covered by loess and aeolian sand. A comprehensive prediction method for the distribution characteristics, development laws, and depth of downward cracks has yet to be established. This article builds on previous research achievements and further optimizes the prediction formula for horizontal surface deformation during the Active Phase. It combines elastic mechanics, soil mechanics, physical similarity simulations, and numerical simulation methods to establish a stress model for loose layers under mining, studying the development laws of surface cracks. Additionally, it considers the mechanical properties of loose layers during rainy and non-rainy seasons and provides a prediction method for the location and depth of mining-induced surface cracks in the Yushenfu mining area.

Geological overview

The Yushenfu mining area (Fig. 1) is located in the centra part of the Ordos Basin (N38°03´ ~ 30°30´/E109.2°30´ ~ 110°55´), bridging the Mu Us Desert and the Loess Plateau. It includes the Yushen, Shenmu North, and Xinmin mining areas, which collectively form a significant coal production base in western China, known for its abundant coal reserves. The area experiences distinct climate variations, with an average annual temperature of 8.4 °C, ranging from a maximum 38.9 °C to a minimum of −27.9 °C. Annual precipitation averages ranges between 400 and 450 mm, with approximately 69% occurring from July to September. Rainfall is highly concentrated, with individual heavy rainfall events often exceeding 10% of the annual total. Additionally, the area faces sever water erosion, impacting about 85% of its land area, with intensities surpassing 500 t/(km2·a).

Geologically, the study area is characterized by a relatively simple structure, with gentle undulations and a broad monocline dipping slightly from southeast to northwest at angles of 1° to 3°. Localized areas exhibit minor faults. The surface is predominantly covered by Quaternary loose deposits (Q), with the stratigraphic sequence as follows: Jurassic Lower Fuxian Formation, Middle Yan’an Formation, Zhiluo Formation, and Anding Formation, followed by Neogene Upper Xinshan Formation, Quaternary Middle and Upper Lishi Formation, Holocene aeolian and alluvial deposits. Coal-bearing formations are more exposed in the eastern part, gradually sloping downward from northwest to southeast, with elevations ranging from + 1200 to + 1300 m above sea level. The coal seams are shallowly buried, with depths increasing towards the Yushen Mining Area as the strata dip westward. The primary coal-bearing formation in the area is the Middle Jurassic Yan’an Formation, which ranges in thickness from 150 to 300 m and contains over 20 coal seams categorized into five main coal-bearing sections. The mineable coal seams include five primary layers in the Shenfu Mining Area ( No.1–2, No.2–2, No.3–1, No.4–2, and No.5–2 ) and four in the Yushen Mining Area ( No.2–2, No.3–1, No.4–3, and No.5–3 ).

The 2–2 coal seam, which is the most extensively mined in the study area, has an average thickness of 4 m and is typically buried at depths ranging of 100 to 300 m, with a bedrock thickness of 150 to 180 m. The surface layer is covered by a relatively thick loose layer, approximately 100 m in thickness, composed mainly of aeolian sand, loess, and red clay, with aeolian sand overlaying the other soils.

The aeolian sand, with an average thickness of 10 m, is formed by wind deposition and exhibits poor cohesion, high looseness, and good permeability. Its cohesion decreases with decreasing water content under constant dry density, while its shear strength initially increases and then decreases with increasing water content33. The loess, primarily composed of silt, is uniform in texture, loose, porous, and weak plasticity. It disintegrates rapidly upon contact with water, has moderate permeability, and is collapsible, with a thickness of about 60 m. In its dry state, loess exhibits high shear strength, which decreases significantly as the moisture content increases34. The Red clay, rich in clay minerals and with fewer pores, demonstrates good cementation, strong cohesion, significant collapsibility, and expansiveness, resulting in high soil strength. The average thickness of the red clay layer is 90 m35.

The surface layer of Yushenfu mining area consists of aeolian sand (10 m thick, loose, permeable), loess (60 m thick, porous, collapsible), and red clay (90 m thick, cohesive, expansive), each displaying distinct mechanical properties that are highly sensitive to moisture content. Combined with high-intensity mining activities and uneven seasonal rainfall, the region’s already fragile ecological environment is further degraded. Given the unique geological conditions and current mining practices in the study area, this research aims to optimize the prediction formula for surface horizontal deformation induced by mining. By establishing a mechanical model for the loose layers during the Active Phase, we investigated the development mechanisms and prediction methods for surface cracks in the study area.

Optimization of horizontal deformation formulas

After coal mining and the formation of goaf areas, the original stress equilibrium of the rock strata is disrupted, leading to stress redistribution and an imbalanced state of deformation and fracturing. This process progresses from the bottom to top, ultimately reaching the surface and causing uneven subsidence and movement of the overlying loose layers. When the horizontal deformation of the loose layer exceeds its ultimate tensile strain, the shear stress surpasses its shear strength, resulting in shear failure characterized by separation of soil and the formation of downward fractures21. Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of horizontal deformation in mining areas.

From Fig. 2, it is evident that surface cracks primarily occur in regions where horizontal tensile deformation peaks within the mining-affected area. To investigate the development location and depth of these surface cracks, it is essential to study the variations in the peak regions of horizontal deformation. Figure 3 depicts the key parameters of the mining influenced area.

The projection of the subsidence basin on the surface forms an ellipse, with the center of the ellipse located at the center of the goaf. The lengths of the two axes depend on the influence radius r and the dimensions of the working face. Under equivalent working conditions, the major axis length of the subsidence basin’s projected ellipse is determined by the length of the working face in the direction of advance, while the minor axis length depends on the length of the working face in the dip direction. The morphology of the subsidence basin during the working face extraction process is influenced by geological conditions (coal seam burial depth H, mining height m, thickness of the bedrock mj, thickness of the loose layer ms), as well as the advancing speed at time t (vtx, vty), the advancing time (tx, ty), and the deviation distance of the turning point(dx, dy). To enhance the accuracy of predicting horizontal deformation at the surface, mathematical methods are utilized to further optimize the horizontal deformation prediction formula.

Taking the derivative of Eq. (1) with respect to time t, we obtain Eq. (2), which describes the relationship between the horizontal displacement velocity vu and the subsidence velocity vx.

where U(x,y,t) is the horizontal displacement at point (x,y) on the ground surface at time t since commencement of mining operations, mm. b is the horizontal displacement coefficient. W(x,y,t) is the subsidence at point (x,y) on the ground surface at time t since commencement of mining operations, mm. x is the horizontal relative position of any point in the soil mass with respect to the mining excavation, m. y is the horizontal relative position of any point in the soil mass with respect to the mining roadway, m. vu is the instantaneous horizontal displacement velocity at point (x,y) on the ground surface at time t since commencement of mining operations, mm/d. vx is the instantaneous subsidence velocity at point (x,y) on the ground surface at time t since commencement of mining operations, mm/d.

The expression for the subsidence velocity vx is given by Eq. (3)36:

where W(x,y,t)max is the final subsidence amount at point (x,y) on the ground surface after full extraction, mm. τ is the time at which the maximum subsidence velocity vmax occurs on the ground surface after full extraction, d. T is the total time elapsed from the commencement of mining operations to when the ground surface reaches its maximum subsidence amount at point (x,y), d. c is a dimensionless coefficient relating to the temporal effects associated with the physical and mechanical properties of the overlying rock strata, with units of 1/a or 1/d.

By combining Eqs. (1), (2), (3) and horizontal surface deformation Eq. (4), we derive the following prediction Eq. (5) for horizontal deformation at any point (x,y) on the ground surface, where subsidence velocity vx serves as a critical parameter.

where ε(x,y,t) is the horizontal deformation at point (x,y) on the ground surface at time t since commencement of mining operations, mm/m. Cd is the dynamic subsidence basin coefficient, Cd = r/(r + d). vtx is the advance velocity along the strike direction of the working face, m/d. tx is the time for advance along the strike direction of the working face, d. dx is the offset distance at the turning point along the strike direction, m. vty is the advance velocity along the dip direction of the working face, m/d. ty is the time for advance along the dip direction of the working face, d. dy is the offset distance at the turning point along the dip direction, m. r is the influence radius, m.

Surface movement is a dynamic process that continuously evolves with the advancement of the working face. Typically, the entire process of surface movement is divided into three phases based on subsidence velocity vx: Initial, Active (vx ≥ 1.67 mm/d), and Weakening (vx≤ 1.67 mm/d) Phases37. During the Active Phase, deformation can account for over 85% of the total, representing the main period for the generation and development of surface cracks. Significant differences exist in the horizontal deformation patterns of surface points near the peak of the Active Phase. Therefore, using the peak subsidence velocity vmax as a boundary, the Active Phase can be further divided into two stages, as depicted in Fig. 4.

In Stage I, subsidence velocity vx increases from 1.67 mm/d to its maximum value. During this stage, the horizontal deformation values are positive, indicating that the surface points are in a region of tensile deformation. Horizontal tensile deformation increases from small values to a peak and then gradually decreases back to zero. During this process, when horizontal tensile deformation exceeds the ultimate deformation limit of the soil, the soil layer fails, propagating along the direction of fractures and causing surface tensile cracks to appear.

In Stage II, subsidence velocity vx decreases from its maximum value to 1.67 mm/d. During this stage, the horizontal deformation values are negative, indicating that the surface points are in a region of compressive deformation. The surface points transition from horizontal tensile deformation to horizontal compressive deformation. Horizontal compressive deformation increases from zero to a peak value and then gradually decreases back to nearly zero.

Based on the probability integral method for predicting surface horizontal deformation, and considering the geological conditions (coal seam depth H, mining height m, bedrock thickness mj, and loose layer thickness ms), the advancement speed of the working face at time t (vtx, vty), advancement time (tx, ty), and offset distance at the turning points (dx, dy), the Active Phase is subdivided into two stages: Active Stage I and Active Stage II, based on the peak subsidence velocity. Using mathematical methods to optimize the prediction equations for surface horizontal deformation, the prediction equations for horizontal deformation during the two stages of the Active Phase were derived as Eqs. (7) and (8).

Mechanism of surface crack development

After determining the horizontal deformation of any point within the loose layer on the surface due to mining activities, it is essential to evaluate the pre-existing stress state within the loose layer to assess whether surface failure will occur. The surface of the Yushenfu mining area predominantly composed of aeolian sand. In geotechnical engineering analysis, aeolian sand is typically simplified as a continuous, homogeneous, and isotropic material under typical stress conditions for analytical purposes38. Using elasticity theory, a mechanical model for the loose layer in the mining-affected area is established to analyze the stress variation patterns in the loose layer at different stages under horizontal deformation. This analysis, combined with the optimized prediction equations (Eqs. (7) and (8)) for surface horizontal deformation, provides a more detailed investigation into the mechanism of surface crack development.

Mechanical model of the surface loose layer

The boundary loose layer of the goaf shifts towards the goaf under the influence of mining, leading to changes in the stress state within the surface loose layer. A mechanical model of the mining-affected surface loose layer was established using elasticity theory (Fig. 5) to examine the relationship between horizontal deformation and the load-bearing capacity of the loose layer.

The loose layer is considered as a continuous, homogeneous, and isotropic fully elastic body, and is analyzed as a semi-infinite plane. In this model, the left side of the loose layer unit experiences distributed loads q(z) due to horizontal deformation, while the surface is subjected to uniform loads q(z0) in the horizontal direction.

Through stress–strain transformation, Eq. (9) establishes the relationship between the horizontal deformation of the loose layer and the distributed load q(z):

where q(z) is the distributed load generated at different depths due to horizontal deformation. q(z0) is the load exerted on the loose layer at depth z0 under the influence of horizontal deformation.

By applying the principle of superposition, the distributed load q(z) acting on the loose layer at any depth due to horizontal deformation can be determined. Since cracks develop downward from the surface, the stress on the loose layer at the surface is initially evaluated. Substituting z0 = 0 into Eq. (9), the relationship between horizontal deformation on the plane at z0 and the applied load is obtained, as shown in Eq. (10).

Based on the expression for horizontal deformation using the probability integral method and considering the relationship between horizontal deformation and the distributed load acting on the loose layer, the expression for the distributed load q(z) acting on the loose layer is derived, as shown in Eq. (11).

where q(z) is the distributed load in the horizontal direction acting on the loose layer at position (x,y,z), N/m. E is the elastic modulus of the loose layer, MPa. μ is the Poisson’s ratio of the loose layer. r is the influence radius, m. tanβ is the tangent of the principal influence angle. z is the vertical distance of any point in the loose layer from the coal seam, m. H is the burial depth of the coal seam, m. Hs is the burial depth of any point in the loose layer, m.

The distributed load q(z) acting on the loose layer unit (x,y,z) depends on the elastic modulus E and Poisson’s ratio μ of the loose layer, as well as the horizontal deformation ε(x,y,z,t).

Force analysis of the loose layer

By combining the optimized equation for predicting horizontal deformation with the relationship between the horizontal deformation of the loose layer and the distributed load q(z), this study characterizes the stress and deformation features of the loose layer under horizontal deformation during Active Phases Stage I and II. This provides a theoretical basis for accurately predicting the location and depth of crack development.

Figure 6 shows that as the advancing working face reaches the surface and exhibits initial deformation (Initial Phase), the boundary of the subsiding basin experiences horizontal tensile deformation on the edges and compression deformation in the central part. With continued coal seam extraction, the moving deformation begins to affect surface points A and B. As the working face progresses further (Active Phase Stage I), the influence area of the subsiding basin continues to expand. The horizontal tensile deformation values at points A and B on the surface exceed the ultimate tensile strain of the surface loose layer, resulting in the formation of tension cracks at points A and B, both located at the boundary of the subsiding basin. After the working face moves past point B (Active Phase Stage II), point A remains in the tensile deformation zone of the basin boundary, where boundary cracks continue to develop. Meanwhile, point B transitions from the tensile deformation zone to the compressive deformation zone, where horizontal compressive deformation values increase continuously. The partial offset between compression and tensile deformation results in some closure of cracks in the central part of the working face (point B). After completion of the working face (Weakening Phase), point B, located in the central part of the subsiding basin, transitions from compression to a neutral zone, where horizontal deformation values are close to zero. Cracks partially heal to a certain extent and remain stable. Points A and C, situated at the basin boundary, maintain their positions within the tensile zone. At this stage, however, the subsidence rate and amount decrease significantly, with boundary cracks almost ceasing to develop.

During the Active Phases Stage I and II, the stress patterns in the surface loose layer exhibit dynamic variations. These stages are differentiated by tensile and compressive deformations, with the boundary point of the subsiding basin serving as the transition point. The surface morphology within the basin during these two stages consists of two oppositely directed arcs, which approximately resemble the hypotenuse of a triangle. Due to the large scale of the basin and the minimal curvature of the arcs, the curved surface can be locally approximated as a straight line, forming a wedge-like structure. By setting the origin of the coordinate system at the intersection of the two stages, the left side of the origin corresponds to the tensile deformation zone, while the right side represents the compressive deformation zone. The angle of the wedge-shaped body can be determined by the slope values (maximum inclination) at the surface points of the boundary at the intersection of the two stages, establishing the stress model of the subsiding basin surface wedge-shaped body under horizontal deformation as depicted in Fig. 7.

The curved surface of the subsidence basin can be approximated as a wedge-shaped body. The wedge angle α can be derived from the tilt value of the surface points. The surface is subjected to a distributed load q(z0) caused by horizontal deformation. Using the semi-inverse method, the general form of the stress function is presented in Eq. (14). Based on the boundary conditions, the stress components at any point within the wedge-shaped body are obtained, as shown in Eq. (16):

where α is the wedge angle, °. z1 is the depth at any point in the loose layer, m. τxz1 is the shear stress acting on the loose layer at depth z1, kPa.

Combining Eqs.(11) and (16) yields the relationship between τxz1 and ε(x,y,z,t), as shown in Eq. (17).

where the wedge angle α is related to the tilt deformation value i of surface points at different times, as shown in Eq. (18). The expected formula for i is provided in Eq. (19).

From Eq. (17), it is evident that the shear stress τxz1 at point (x,y,z) in the loose layer is dependent on the horizontal deformation ε(x,y,z,t) at time t.

Considering the dynamic changes in surface horizontal deformation, the development of surface cracks during the two stages of the Active phase can be analyzed separately. Figure 8 illustrates the distribution pattern of horizontal deformation on the surface.

During the advancement of the working face, surface points will experience 'tensile zone-compression zone-neutral zone’. After the working face is completely extracted, the distance between the permanent cracks on both sides of the subsidence basin cross-section is the sum of: (1)the distance from the permanent crack on the cut-off side to the cut-off, (2)the advancement distance, and (3)the distance from the permanent crack on the stop line side to the stop line. If the development position of the permanent crack on one side is determined, the position of the crack on the other side can be established based on the relative positions of the cracks on both sides.

Combining the stress and deformation conditions of the two stages of surface horizontal deformation during the Active phase, the relationship between τxz1 and ε(x,y,z,t) for Active Phase Stage I is obtained by combining Eqs. (7) and (17), as shown in Eq. (20).

Combining Eqs.(8) and (17), the relationship between τxz1 and ε(x,y,z,t) for Active Phase Stage II is obtained, as shown in Eq. (21).

Through the theoretical derivation of the stress on the loose layer soil during the two stages of the Active Phase, the stress-deformation relationships under horizontal deformation for the two stages are obtained, as shown in Eqs. (20) and (21). Further analysis is needed, incorporating the inherent properties of the loose layer and its failure criteria, to accurately predict the specific location and depth of crack development.

Prediction method for the location and depth of surface cracks

At a specific critical depth z, the additional stress induced by horizontal deformation exceeds the shear strength of the loose layer, bringing it to a critical cracking state. Below this critical depth z, the lateral horizontal stress is below the critical value, and no further cracking occurs in the loose layer. According to soil strength theory and the ultimate equilibrium condition of its failure, the shear stress τxz1 at any point in the soil can be compared to the soil shear strength τf can lead to three situations: when τxz1 < τf, the soil remains intact and no cracks form; when τxz1 > τf, the soil undergoes shear failure and cracks develop; when τxz1 = τf, the soil is in an ultimate equilibrium state.

The shear stress in the loose layer is proportional to the distributed load q(z) caused by horizontal deformation. As the depth z increases, q(z) also increases, consistent with the top-to-bottom development characteristic of surface cracks. Therefore, by determining whether the loose layer unit at the surface has failed, the location and depth of mining-induced cracks can be established.

The surface loose layer in the research area primarily consists of aeolian sand. At any cross-section y in the subsidence basin, the position x where surface cracks initiate can be determined by incorporating the shear strength τf of the aeolian sand from Eq. (17), as shown in Eq. (22).

Considering the morphology of the subsidence basin, the relationship between the initiation position x of surface cracks and the relative depth z1 of crack development at x, determined by the crack development pattern (perpendicular to the surface), is expressed in Eq. (23).

At the surface of the subsidence basin, the horizontal position x of a surface point is the tangent value of the depth z1tana (as described in the horizontal deformation effect on the stress model of the subsidence basin). Therefore, by substituting Eq. (23) into Eq. (22), the variables x and z1tana are eliminated, leading to the predictive formula for the surface crack initiation position x, as shown in Eq. (24).

By substituting Eq. (16) and (23) into Eq. (17), the expression for the shear stress τxz1 on the loose layer at depth z1 is obtained, as shown in Eq. (25).

Substituting the shear strength τf of the aeolian sand into Eq. (25), the depth z1 at which crack development occurs is determined, as shown in Eq. (26).

The essence of crack development lies in the fact that additional stresses induced by horizontal deformation exceed the inherent strength of the loose layer. Moisture content significantly affects the strength of loose layer, so it is essential to distinguish between the mechanical parameters of the loose layer for rainy and non-rainy seasons during the calculation process. The respective strength values for these conditions should be substituted into Eqs.(22) to (26) for accurate predictions.

Engineering case verification

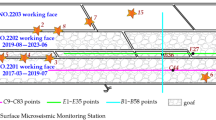

This study focuses on mining coal seam No.2–2 at a specific mine in the Yushenfu mining area. It combines theoretical predictions, physical simulations, and numerical modeling to analyze surface crack development on the 112201 working face. The objective is to compare the evolutionary patterns of subsidence-induced surface crack development with field observations to validate the reliability of prediction methods for surface cracks in the Yushenfu mining area. Figure 9 illustrates the schematic layout of the mining area.

The 112201 working face has a strike length of 4065 m and a dip length of 350 m, with a burial depth of 367 m. The coal seam thickness ranges from 4.2 to 6.3 m, averaging 5.8 m. The coal seam is nearly horizontal, and the overlying stratum predominantly consists of fine sandstone and siltstone, with an average thickness of approximately 215 m. Surface elevation ranges from + 1283 m to + 1330 m, with the pseudo-roof composed of 0.2 to 0.5 m of carbonaceous mudstone, the immediate roof consisting of 2.67 to 3.37 m of fine-grained sandstone, and the main roof made up of medium-grained sandstone, varying in thickness from 14.23 to 35.29 m. The surface of the mining area is covered by Quaternary aeolian sand. The mining method involves fully mechanized mining with caving roof management, with an average extraction thickness of 5.8 m. Detailed mining parameters are presented in Table1. Mining operations began in September 2018 and concluded in December 2019. Observations of surface cracks indicate that boundary cracks are distributed within a “belt area” ranging from 18 to 56 m outside the roadway, with crack depths varying from 0.45 to 2.32 m39,40.

Theoretical prediction

Non-rainy season

The mechanical parameters measured from samples with natural moisture content are as follows: shear strength τf = 65 kPa, soil elastic modulus E = 18.5 MPa, and Poisson’s ratio μ = 0.35. By substituting the shear strength into Eq. (24), the critical horizontal deformation value ε(x,y,z,t) under non-rainy season conditions is obtained, as shown in Eq. (27).

Using the optimized horizontal deformation prediction formula, the horizontal deformation during the mining process of the working face calculated. The predicted horizontal deformation value before optimization (25) is computed and compared with the optimized horizontal deformation value and the actual measured surface horizontal deformation. The predicted surface horizontal deformation and crack positions are plotted, as illustrated in Fig. 10.

As illustrated in Fig. 10a, the formula predicts maximum surface horizontal deformations of 9.57 mm/m and −9.61 mm/m before optimization, and 15.88 mm/m and −9.61 mm/m after optimization. The measured maximum horizontal deformations are 13.49 mm/m and −9.76 mm/m. The average relative error between the predictions using the traditional probabilistic integration formula (during the Active phase) and the measured values is 25.93%. In contrast, the average relative error between the predictions using the optimized formula (during the Active phase) and the measured values is 11.55%. This indicates that the optimized horizontal deformation values closely match the measured values.

In Fig. 10b, the surface y-coordinates corresponding to ε(x,y,z,t) = 4.74 mm/m are identified. Solving this Equation gives y = −8.05 m and y = 48.73 m, indicating that surface cracks occur between 8.05 m outside and 48.73 m inside the roadway of the working face. This range aligns with the observed crack occurrence area of −18 to 56 m as measured. When the working face advances to the 140 m position, the surface is in a critical cracking state.

Using the optimized surface deformation prediction formula, the surface tilt deformation at locations where cracks are expected to appear is predicted. Using Eq. (25), the shear stress acting on the soil is less than the shear strength, crack development ceases, enabling the prediction of crack development depth. Figure 11 illustrates the predicted surface tilt deformation.

As depicted in Fig. 11, the tilt deformation value i at the crack development location y = −8.05 m is 27.05 mm/m, whereas at y = 48.73 m, it computes to 8.90 mm/m. The inclination angle α is calculated, as given in Eq. (28).

As the working face continues to advance, the horizontal deformation of the surface point y changes. By substituting the determined crack development locations y and inclination angles α into Eq. (26), the crack development depth z1 at the surface point y, when it reaches the extreme horizontal deformation, is calculated to range from 0.62 to 2.27 m.

During the non-rainy season, surface cracks are predicted to occur between 8.05 m outside and 48.73 m inside the roadway of the working face, with an estimated development depth ranging from 0.62 to 2.27 m.

Rainy season

Under the influence of precipitation, the surface soil moisture content approaches saturation. The mechanical parameters obtained from saturated specimens in laboratory experiments are as follows: τf = 40 kPa, E = 14.5 MPa and μ = 0.40. By incorporating shear strength into Eq. (24), the critical horizontal deformation value ε(x,y,z,t) during the rainy season can be determined, as expressed in Eq. (29).

Figure 12 represents the predicted surface horizontal deformation and potential crack locations. The surface y-coordinates corresponding to ε(x,y,z,t) = 3.85 mm/m are identified as y = −14.82 m and y = 50.16 m. These value indicate that surface cracks are likely to develop within a range extending from 14.82 m outside and 50.16 m inside the roadway of the working face. This predicted range shows good agreement with the observed crack occurrence area of −18 to 56 m. When the working face advances to the 100 m position, the surface reaches a critical state for cracking initiation.

The optimized surface deformation prediction formula was employed to estimate the surface tilt deformation at potential crack locations, combined with the predicted crack development depth. The resulting surface tilt deformation is illustrated in Fig. 13.

As shown in Fig. 13, the tilt value i at the crack development location y = −14.82 m is 25.28 mm/m, while at y = 50.16 m, it is 8.79 mm/m. The inclination angle α was subsequently calculated using Eq. (30).

With continued advancement of the working face, the surface horizontal deformation undergoes changes. By substituting the determined crack development locations y and inclination angle α into Eq. (26), the range of crack development depth z1 at the surface point y can be established when the horizontal deformation reaches its maximum value. The calculated depth range for z1 is from 0.39 to 1.68 m.

During the rainy season, surface cracks are predicted to develop within a zone extending from 14.82 m outside to 50.16 m inside the roadway of the working face, with an estimated development depth ranging from 0.39 to 1.68 m.

Physical experimentation and numerical simulation validation

Based on the mining conditions of the 112201 working face in the Yushenfu mining area, a physical similarity simulation experiment and a 3DEC numerical model were established. The mechanical parameters of the coal seam and overlying strata are provided in Table 2. To replicate actual mining conditions, the physical similarity simulation model was constructed with dimensions of 3 m × 0.2 m × 1.7 m (length × width × height), employing a geometric similarity ratio of 1:250. River sand served as the primary material, with gypsum, white powder, and vaseline were used as cementing agents. Detailed material composition and proportions for the physical similarity simulation are outlined in Tables 2 and 3. The physical similarity simulation test model is illustrated in Fig. 14a.

In accordance with the rock layer grouping and discrete treatment specified in Table 3, joints and bedding planes were configured based on the characteristics of each rock layer, and grids were established accordingly. The model boundaries were set with fixed lateral constraints, allowing the top surface to move freely. The dimensions of the numerical model are 900 m × 20 m × 400 m (length × width × height). The Mohr–Coulomb constitutive model was applied to the entire model. The numerical simulation model is illustrated in Fig. 14b.

Non-rainy season

When the working face advanced to 130 m, the maximum surface horizontal deformation reached 4.93 mm/m. At this stage, the shear stress in the loose layer exceeded its shear strength, causing minor downward cracks to appear on the left side of the surface above the goaf. The physical similarity simulation experiment shows a development depth of 0.08 m (Fig. 15a), while the numerical simulation indicated a slightly greater depth of 0.1 m (Fig. 15b).

Following the appearance of the first surface crack, dynamic monitoring of the surface cracks on top of the model was conducted sequentially. As the working face advanced to 200 m, the extreme value of horizontal deformation increased to 5.33 mm/m, and the cracks propagated further downward. The physical similarity simulation experiment measured a crack development depth of 1.07 m (Fig. 16a), whereas the numerical simulation showed a depth of 0.96 m (Fig. 16b).

When the working face reached to 350 m, the maximum horizontal deformation peaked at 5.87 mm/m. At this point, the shear stress at the crack tip exceeded the strength limit of the soil, causing the cracks to continue propagating and deepening. The physical similarity simulation experiment showed that the crack development depth increased to 2.18 m (Fig. 17a), while the numerical simulation indicated a depth of 2.03 m (Fig. 17b).

At 500 m of advancement, the extreme value of horizontal deformation reached 6.03 mm/m. On the left side of the goaf, the physical similarity simulation showed that the development depth of the downward cracks was measured at 2.46 m, while the numerical simulation indicated a development depth of 2.39 m (Fig. 18a), which is essentially the same as the crack development depth at 350 m of advancement. On the right side of the goaf, the development depth was measured at 1.63 m (Fig. 18b).

Based on the results of physical experiments and numerical simulations, the maximum development depth of subsidence cracks on the left side of the goaf during the non-rainy season ranges from 0.59 to 2.46 m, distributed within a zone extending from 7.72 m outside to 47.23 m inside the goaf. On the right side, the final development depth of subsidence cracks ranges from 0.32 to 1.63 m, distributed within a zone extending from 8.42 m outside to 43.95 m inside the goaf.

Rainy season

During natural rainfall, rainwater infiltration alters the moisture content of the surface soil, significantly impacting soil strength. By modifying the mechanical parameters of the surface soil, the development patterns of surface cracks during the rainy season can be simulated. When the working face advanced to 100 m, the maximum surface horizontal deformation reached 4.12 mm/m. The physical similarity simulation experiment indicated that the development depth of downward cracks on the left side of the goaf reached 0.03 m (Fig. 19a), while the numerical simulation showed a slightly greater depth of 0.05 m (Fig. 19b).

As the working face progressed to 200 m, the maximum horizontal deformation increased to 4.5 mm/m, and the cracks continued to deepen. The physical simulation experiment showed a crack development depth of 0.65 m (Fig. 20a), whereas the numerical simulation indicated a depth of 0.77 m (Fig. 20b).

When the working face advanced to 360 m, the maximum horizontal deformation reached 5.32 mm/m. The physical simulation experiment showed a crack development depth of 1.34 m on the left side of the goaf (Fig. 21a), while the numerical simulation reveals a depth of 1.60 m (Fig. 21b).

At 500 m, the maximum horizontal deformation reached 5.61 mm/m. The physical similarity simulation experiment yielded a crack development depth of 1.75 m on the left side of the goaf (Fig. 22a), while the numerical simulation provides a depth of 1.68 m (Fig. 22b). This is comparable to the crack development depth observed at 360 m. Additionally, downward surface cracks have appeared on the side of the working face where mining ceased, with a development depth of 1.58 m.

Based on the results of physical experiments and numerical simulations, during the rainy season, the final development depth of subsidence cracks on the left side of the goaf ranged from 0.41 to 1.75 m, distributed within a zone extending from 12.63 m outside to 53.21 m inside the goaf. On the right side, the final development depth of subsidence cracks ranges from 0.52 to 1.58 m, with the distribution extending from 14.9 m outside to 52.1 m inside the goaf.

The results of the physical simulation, numerical simulation, and theoretical calculations regarding the location and depth of surface cracks were summarized in Table4.

Figure 23 illustrates the relative positions of observed and predicted cracks. As depicted in Fig. 23, during the non-rainy season, theoretical predictions indicated that cracks occur between 8.05 m outside and 48.73 m inside the working face’s roadway. During the rainy season, predicted cracks are expected between 14.82 m outside and 50.16 m inside the working face’s roadway. Both the non-rainy and rainy season predicted crack locations fall within the observed range (18 m outside to 56 m inside the roadway).

Theoretical predictions estimated that during the non-rainy season, crack development depths range from 0.62 to 2.27 m, while during the rainy season, they ranged from 0.39 to 1.68 m. Actual observed crack development depths ranged from 0.45 to 2.32 m, indicating close agreement between predicted and observed values. (The predicted development depths were slightly underestimated due to the omission of secondary crack effects31). During the rainy season, surface downward cracks are relatively shallower (by 0.23 to 0.59 m) and have a broader distribution range (14.44% wider) compared to non-rainy season cracks.

In summary, the theoretical calculations for the locations and depths of surface downward cracks in the boundary area of the 112201 working face’s No.2–2 coal seam, following mining in the Yushenfu mining area, were consistent with results obtained from physical similarity simulations, numerical simulations, and field observations. This confirmed the reliability of the prediction methods for surface crack development in the Yushenfu mining area.

Conclusion

-

Based on the probabilistic integral method for predicting surface horizontal deformation, the subsidence velocity peak is used to divide the Active Phase into two stages. Optimized prediction equations for horizontal surface deformation are developed.

-

Surface cracks occur when the additional stress induced by horizontal deformation exceeds the shear strength of the loose layer. A prediction method for the position and depth of surface crack development is established, demonstrating that the position and depth of cracks primarily depend on the inherent properties of the loose layer (shear strength τf, elastic modulus E, Poisson’s ratio μ) as well as the horizontal deformation ε.

-

Considering the seasonal characteristics of Yushenfu mining area, the proposed method for predicting the location and depth of surface crack development is applied. Theoretical predictions for surface cracks at the 112201 working face during both the rainy and non-rainy seasons are consistent with the results obtained from physical similarity simulations, numerical simulations, and field measurements.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Xie, X. S. et al. Study on evaluation and prediction of the degree of surface damage caused by coal mining. Front. Earth Sci. 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2021.805248 (2022).

Chen, C. & Hu, Z. Q. Research advances in formation mechanism of ground crack due to coal mining subsidence in China. J. China Coal Soc. 43, 810–823. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2017.0942 (2018).

Cui, X. M. et al. Method and problems for subsidence prediction in entire process induced by underground mining. J. China Coal Soc. 47, 2170–2181. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.fq22.0009 (2022).

Yan, W. T., Guo, J. T. & Yan, S. G. Difference in surface damage between deep and shallow mining of underground coal resources in China. Sustainability. 15, 7296. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097296 (2023).

Li, X. B. et al. Study of water-conducting fractured zone development law and assessment method in longwall mining of shallow coal seam. Sci. Rep. 12, 7994. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12023-9 (2022).

Li, J. W. & Liu, C. Y. Formation mechanism and reduction technology of mining-induced fissures in shallow thick coal seam mining. Shock. Vib. 01, 1980817. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1980817 (2017).

Li, H. et al. Characteristics and distribution of tectonic fracture networks in low permeability conglomerate reservoirs. Sci Rep. 15, 5914. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90458-6 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Developmental features, influencing factors, and formation mechanism of underground mining-induced ground fissure disasters in China: a review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20, 3511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043511 (2023).

Liu, H., Deng, K. Z., Lei, S. G., Bian, Z. F. & Chen, D. Y. Dynamic developing law and governance standard of ground fissures caused by underground mining. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 34, 884–890. https://doi.org/10.13545/j.cnki.jmse.2017.05.009 (2017).

Li, Z. H., Pang, Y. K., Bao, Y. S. & Ma, Z. Y. Research on surface failure law of working faces in large mining height and shallow buried coal seam. Adv. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8844249 (2020).

Zhang, Y. J., Lian, X. G., Yan, Y. G., Zhu, Y. H. & Dai, H. Y. Study on the development Law of mining-induced ground cracks under gully terrain. Remote Sens. 14, 5985. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14235985 (2022).

Yan, Y. G., Yan, W. T., Dai, H. Y. & Guo, J. T. Distribution characteristics and formation mechanism of surface crack induced by extrathick near horizontal seam mining: an example from the Datong coal field. China. Adv. Civ. Eng. 01, 5545128. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5545128 (2021).

Zhou, D. W. et al. Formation and development mechanism of ground crack caused by coal mining: effects of overlying key strata. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78, 1025–1044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-017-1108-2 (2019).

Hu, Z. Q., Wang, X. J. & He, A. M. Distribution characteristic and development rules of ground fissures due to coal mining in windy and sandy region. J. China Coal Soc. 39, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2013.1289 (2014).

Hou, E. et al. Laws and prevention methods of ground cracks in shallow coal seam mining. Coal Geo. Explor. 50, 30–40. https://doi.org/10.12363/issn.1001-1986.22.05.0427 (2022).

Liu, H., Deng, K. Z., Zhu, X. J. & Jiang, C. L. Effects of mining speed on the developmental features of mining-induced ground fissures. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78, 6297–6309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-019-01532-z (2019).

Huang, Q. X. Research on roof control of water conservation mining in shallow seam. J. China Coal Soc. 42, 50–55. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2016.5006 (2017).

Cao, J. & Huang, Q. X. Regularity and control of overburden and surface fractures in shallow-contiguous seams. Coal Geo. Explor. 49, 213–220. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-1986.2021.04.026 (2021).

Yu, X. Y., Li, B. B., Li, R. B., Duan, W. S. & Liu, P. Analysis of mining damage in huge thick collapsible loess of western China. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 37, 43–47 (2008).

Wang, P., Yu, X. Y. & Liu, J. Study on cracking failure mechanism of surface ground above underground high cutting coal mining face in shallow mining depth seam. Coal Eng. 46, 84–86 (2014).

Cao, J. & Wei, X. M. Research on mining-induced surface soil cracking mechanism and development depth of downward fracture. Eng. Failure Anal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108180 (2024).

Tang, F. Q. & Zhang, J. Formation mechanism of cracks caused by mining in western China thick loess mine area. J. Liaoning Tech. Univ. 33, 1466–1470. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1008-0562.2014.11.006 (2014).

Xu, N. Z., Gao, C., Ni, X. Z. & Liu, M. H. Study on surface cracks law of fully-mechanized top coal caving mining in shallow buried depth and extra thick seam. Coal Sci. Tech. 43, 124–128. https://doi.org/10.13199/j.cnki.cst.2015.12.025 (2015).

Wu, K., Li, L., Ao, J. F. & Hao, G. Discussion on limit development depth of cracks in surface soil mass caused by mining subsidence. Coal Sci. Tech. 38, 108–111. https://doi.org/10.13199/j.cst.2010.06.109.wuk.024 (2010).

Zhao, B. C., Sun, H., Guo, Y. X. & Yang, X. Dynamic evolution of water-conducting cracks in shallow seam mining with thick alluvium. Coal Eng. 53, 100–105. https://doi.org/10.11799/CE202110020 (2021).

Feng, D., Hou, E. K., Xie, X. S., Wei, J. B. & Hou, P. F. Differences in the dynamic evolution of surface crack widths at different locations in the trench slope area and the mechanisms: A case study. Environ. Geochem. Health. 45, 7161–7182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-022-01452-0 (2023).

Liu, Y., Cao, S. & Liu, Y. The improved Knothe time function for surface subsidence. Sci. Survey. Mapp. 34, 16–31 (2009).

Wang, J. B., Liu, X. R. & Liu, X. J. Dynamic prediction model for mining subsidence. J. China Coal Soc. 40, 516–521. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2014.0583 (2015).

Zhang, X. S., Yan, S. B., Tan, H. C. & Dong, J. Y. A time function-based prediction model of mining subsidence: application to the Barapukuria coal mine. Bangla. Sci. Rep. 12, 18433. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23303-9 (2022).

Zhang, B. & Cui, X. M. Optimization of segmented Knothe time function model for dynamic prediction of mining subsidence. Rock and Soil Mech. 38, 541–548. https://doi.org/10.1628/j.rsm.2017.02.030 (2017).

Huang, L. T. & Wang, J. Z. Study on the three stages and deformation velocity of dynamic surface subsidence deformation. J. China Coal Soc. 31, 420–424 (2006).

Chang, Z. Q. & Wang, J. Z. Study on time function of subsidence the improved Knothe time function. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 22, 1496–1499 (2003).

Song, Y. X., Peng, J. J., Wang, Z. J., Li, X. A. & Zhao, X. F. Test study on mechanical characteristics of aeolian sand in Mu Us desert. J. Eng. Geo. 18, 894–899 (2010).

Dai, K. W. Research and Control of Surface Subsidence Disaster of Minging in the Thick Loess Covered Area (Xi’An University of Science and Technology, 2010).

Zhao, B. C. et al. Proportion optimization study and application of similar materials to laterite aquiclude. Min Research. Dev. 40, 60–65. https://doi.org/10.13827/j.cnki.kyyk.2020.08.013 (2020).

Zhang, B. Establishment of Dynamic Prediction Model and Implementation of the Algorithm for Mining Subsidence (China University of Mining and Technology, 2017).

Yu, X. Y. & Zhang, E. Q. Mining Damage (China Coal Industry Publishing House, 2010).

Wang, C. Soil Mechanics (Geological Publishing House, 2010).

Xie, X. S. et al. Development law and characteristics of surface cracks caused by coal mining in Yushenfu mining area. Chinese J. Eng. 45, 44–53. https://doi.org/10.13374/j.issn2095-9389.2021.06.29.001 (2023).

Hou, E. et al. Development law of ground cracks induced by fully-mechanized mining of medium-buried coal seams. J. Min Saf Eng. 38, 1178–1188. https://doi.org/10.13545/j.cnki.jmse.2020.0293 (2021).

Jiang, Y. Study of Deformation Law of Overlying Strata Induced by Mining in Main Coal Seam of Xiaobaodang No.1 Well (Xi’an University of Science and Technology, 2021).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52074208) and Department of Science and Technology of Shaanxi (2023-LL-QY-02).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bingchao, Z., Xinyi, F., Yang, Z. et al. A prediction method for mining-induced surface cracks in Yushenfu mining area. Sci Rep 15, 9979 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94273-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94273-x