Abstract

To explore the impact of ultrasound-guided proximal adductor canal and pes anserinus tendon block on early recovery after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery via daytime knee arthroscopy. A total of 127 patients, aged 18–60 years, with ASA class I-II, undergoing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction via knee arthroscopy under general anesthesia with laryngeal mask airway intubation, were selected. These patients were randomly divided into three groups: Group C (43 cases), Group N1 (41 cases), and Group N2 (43 cases). Control group C: received proximal block of the adductor canal with 0.5% ropivacaine (15 ml); Experimental group N1: received proximal block of the adductor canal combined with tendon block of the pes anserinus with 0.5% ropivacaine (15 ml per site); Experimental group N2: received proximal block of the adductor canal combined with tendon block of the pes anserinus with 0.5% ropivacaine plus 5 mg dexamethasone (15 ml per site). Record the VAS scores at each time point after awakening, 3 h after surgery, 6 h after surgery, 12 h after surgery, 24 h after surgery, 48 h after surgery, and 72 h after surgery during rest and knee flexion activities of the knee joint. Record the quadriceps muscle strength after awakening, Ramsay sedation score after awakening, time of first ambulation after surgery, and the amount of sufentanil, propofol, and remifentanil used during the operation. Record the amount of tramadol and flurbiprofen axetil added postoperatively. Record the anxiety scores and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder scores before and 3 days after surgery. Record the occurrence of breakthrough pain and adverse reactions 3 days after surgery. Compared with Group C, both Group N1 and Group N2 showed significantly lower rest and activity VAS scores at all time points on postoperative day 3 (P < 0.05), earlier time to first ambulation after surgery (P < 0.05), significantly lower HADS-A scores and sleep scores on postoperative day 3 (P < 0.05), significantly higher Ramsay sedation scores after awakening (P < 0.05), and significantly reduced use of additional tramadol and flurbiprofen axetil after surgery (P < 0.05). The intraoperative sufentanil dosage was also significantly reduced (P < 0.05). There were no statistically significant differences in quadriceps muscle strength and adverse reactions during the awakening period among the three groups (P > 0.05). Ultrasound-guided proximal adductor canal and pes anserinus tendon block (15 ml of 0.5% ropivacaine each) can effectively alleviate pain 3 days after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery under knee arthroscopy, with good analgesic effects, and has minimal impact on quadriceps muscle strength after awakening, promoting early postoperative ambulation; at the same time, this blocking method can reduce the occurrence of postoperative anxiety and sleep disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) via knee arthroscopy is currently the preferred surgical method for treating anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries. This surgery boasts significant advantages such as minimal trauma, short operation time, precise efficacy, few complications, and rapid postoperative recovery. It meets the criteria for day surgery and has been widely adopted in day surgery settings. However, despite ACLR being a minimally invasive surgery, procedures such as establishing tibial and femoral tunnels, harvesting autologous tendons, and fixing transplanted tendons during the surgery may still cause significant trauma. The incidence of postoperative pain is high, especially the severe pain rate in the early postoperative period, which can reach up to 60%1,2,3. Patients often complain of moderate to severe pain postoperatively, and even experience explosive pain, which affects their sleep quality, appetite, and other functions4,5,6. It may even lead to the occurrence of anxiety and depression, seriously affecting the quality of patient recovery. Clinically, the multi-modal analgesia regimen for ACLR has been continuously optimized, with ultrasound-guided nerve block playing a significant role. Femoral nerve block (FNB) is a commonly used approach for postoperative pain management after knee surgery. However, FNB tends to affect its muscular branches, often resulting in weakened quadriceps muscle strength in the affected limb after surgery7, which increases the risk of falls and affects early postoperative mobility.A study8 indicates that ultrasound-guided adductor canal block (ACB) has a similar analgesic effect to FNB, and it almost does not affect quadriceps muscle strength, offering better safety. Traditional beliefs suggest that ACB can effectively alleviate pain in the anterior and medial parts of the knee joint, but its analgesic effect on the posterior and lateral parts of the knee joint is not as pronounced. The proximal end of the adductor canal is innervated by the posterior branch of the obturator nerve. By injecting local anesthetic at this site, theoretically, it is possible to block the joint branch of the posterior branch of the obturator nerve. Furthermore, the anesthetic solution may even descend through the intermuscular space to the popliteal fossa, blocking the sciatic nerve or its branches, thereby blocking the posterior and lateral parts of the knee joint.However, the pain caused by tendon transplantation and tendon harvesting sites after ACLR surgery is often overlooked. This area of pain can be unbearable for patients postoperatively. Therefore, whether injecting a certain amount of local anesthetic at the tendon harvesting site of the pes anserinus tendon before surgery can alleviate postoperative pain in this area has not been studied either domestically or internationally. This study aims to investigate the impact of combined proximal adductor canal and pes anserinus tendon block on early recovery after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery under knee arthroscopy, providing evidence for the selection of clinical anesthesia and analgesia methods.

Materials and methods

Participants

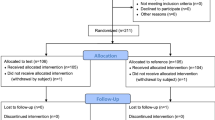

This is a prospective cohort study with a randomized single blind design. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, with the ethics number 2023-CR-126. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.The patient or their family member signs the informed consent form. The patient or their family member signs the informed consent form. Patients undergoing unilateral ACLR from September 2023 to January 2024, with no gender limitation, aged 18–60 years, and ASA class I-II, were selected. Exclusion criteria: infection at the puncture site, preoperative neurological dysfunction or central nervous system disease, severe psychological issues, history of psychiatric illness, coagulation dysfunction, history of chronic pain, drug dependency, allergy to any component of analgesics, and use of other analgesics within 24 h. Exclusion criteria: Subjects who withdrew from the study midway; changes in surgical or anesthesia methods; failure of nerve block.

Sample size calculation

This study employs a two-sided test with a significance level of α = 0.05 and a power of 0.8. The primary outcome measures include the duration of sensory blockade in the lower limb nerves, along with other secondary measures. The primary outcome measures include VAS score and other secondary measures.In the preliminary experiment, 10 participants were recruited for each of the three groups. The mean ± standard deviation of VAS scores for the control group, experimental group 1, and experimental group 2 were 4 ± 0.68, 3 ± 0.86, and 3 ± 0.77, respectively. Based on the preliminary data, a one-way ANOVA was used to calculate an effect size of 0.292, with a between-group mean square of approximately 3.33, a within-group mean square of approximately 0.598, and an F-value of approximately 5.57. Consequently, the effect size in this study fell within the large effect range (taken as 0.3). Parameters were input into G*Power 3.1.9.7 software for calculation using the F-test option, with the number of groups set to 3. The total sample size was calculated as 111 participants. Considering an estimated dropout rate of approximately 5%, a total of 120 participants were required to ensure 111 evaluable individuals.

Grouping and processing

One day before surgery, educational information on observation indicators was provided, and records were kept using the Wenjuanxing platform.Patients were randomly divided into three groups according to the random number table method: the proximal block group of the adductor canal (Group C), the proximal block group of the adductor canal combined with the pes anserinus tendon (Group N1), and the proximal block group of the adductor canal combined with the pes anserinus tendon and dexamethasone (Group N2). All nerve block procedures were performed by the same experienced anesthetist after anesthesia induction.

Nerve block

Adductor canal proximal block

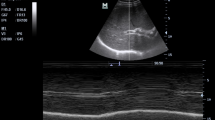

The patient lies down, with legs slightly separated, and the affected limb is slightly abducted and externally rotated to fully expose the medial thigh area. Select a linear array probe and perform sterile processing. Place the probe horizontally on the inner thigh, perpendicular to the femur. Adjust the direction and angle of the probe to locate the medial edge of the sartorius muscle and the medial edge of the long adductor muscle. At the junction of the tendons of these two muscles, observe the tendinous plate structure of the adductor canal, which is marked as the entrance of the adductor canal. Move the ultrasound probe downwards and outwards by about 1–2 cm to clearly display the sonographic images of the sartorius muscle, long adductor muscle, and medial femoral muscle. Between these three muscles, the pulsating sonographic image of the superficial femoral artery can be observed. On the lateral side of the superficial femoral artery, the adductor canal structure can be seen (Fig. 1A), which is marked as the proximal end of the adductor canal .Using the in-plane puncture technique, a 22G nerve block needle is inserted into the skin from the lateral end of the probe. Slowly advancing towards the target nerve, the needle tip passes through the sartorius muscle, the sub-sartorius space, and the adductor magnus muscle membrane. Once there is no blood or air upon withdrawal, local anesthetic can be injected. Under ultrasound, the diffusion of local anesthetic solution within the adductor canal can be observed (Fig. 1B).

Pes anserinus tendon block

The patient lies in a supine position with the knee slightly bent. The high-frequency linear array probe is placed obliquely along the long axis on the inner side of the knee joint cavity, with the upper edge of the ultrasound probe rotated approximately 20° towards the patella. The high-echogenic medial femoral condyle and tibial plateau are visible, and the dense high-echogenic medial collateral ligament of the tibia covers the triangular medial meniscus, At this time, slowly move the ultrasound probe downwards while rotating it clockwise (for the right knee) or counterclockwise (for the left knee) until the tendons of the pes anserinus (sartorius tendon, gracilis tendon, semitendinosus tendon) are visible on the ultrasound image (Fig. 2A) crossing the medial collateral ligament, Using the in-plane needle insertion technique, a 22G nerve block was injected through the lateral end of the probe into the skin, reaching the target location of the surface of the gracilis and semitendinous tendons (Fig. 2B). It can be seen that the local anesthetic solution diffuses fully on the tendon surface.

Ultrasound image of the proximal saphenous nerve in the adductor canal (A), Ultrasound image of needle insertion in the proximal plane of the adductor canal (B). ALM, adductor longus muscle; ACA, adductor canal aponeurosis; SM, sartorius muscle; SFA, superficial femoral artery; PAC, proximal adductor canal; VM, vastus medialis; SN, saphenous nerve; RP, ropivacaine; FA, femoral vein.

Anesthesia method

After the patient enters the room, monitor their electrocardiogram (ECG), non-invasive blood pressure (BP), pulse oximetry (SPO2), and bispectral index (BIS). Establish an intravenous line and administer lactated Ringer’s solution at a rate of 4–6 ml/ (kg·hr) via intravenous drip. Anesthesia induction: Use propofol TCI at a concentration of 2–4 µg/ml and remifentanil TCI at a concentration of 3.0 ng/ml, and administer 0.2 µg/kg of sufentanil intravenously. After the patient loses consciousness, administer 0.2 mg/kg of cisatracurium besilate intravenously. Once muscle relaxation is complete and the BIS value drops to 40–60, insert the laryngeal mask airway for mechanical ventilation. Set the oxygen concentration to 60%, Vt to (6–8) ml/kg, I: E to 1: 2, and RR to 12–15 breaths per minute for mechanical ventilation. Maintain PetCO2at (35–45) mmHg. During the operation, use a warm air blower to maintain normal body temperature. Anesthesia maintenance involves using propofol TCI at a concentration of (1.5–2.5) µg/ml and remifentanil TCI at a concentration of (1.0–3.0) ng/ml. The infusion rate of anesthetic drugs is adjusted based on the patient’s BIS value and hemodynamic parameters. When there are fluctuations in heart rate and blood pressure, an additional 10 µg of sufentanil is administered. To prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting, dexamethasone (10 mg) and ondansetron (8 mg) are routinely administered before surgery9. No additional muscle relaxants are administered 30 min before the end of surgery. The maintenance medication is stopped during skin suturing, and no additional analgesics are administered before removing the laryngeal mask. After the patient regained consciousness and the laryngeal mask was removed, a rescue analgesia was administered with tramadol 100 mg via intravenous injection based on a visual analog scale (VAS) score of > 3. If ineffective, flurbiprofen axetil 50 mg was added.

Observation indicators

Record the VAS scores during rest and knee flexion at each time point after awakening, 3 h after surgery, 6 h after surgery, 12 h after surgery, 24 h after surgery, 48 h after surgery, and 72 h after surgery. Record the quadriceps muscle strength after awakening, Ramsay sedation score after awakening, time of first ambulation after surgery, intraoperative sufentanil dosage, propofol dosage, remifentanil dosage, postoperative additional tramadol and flurbiprofen axetil administration, preoperative and postoperative 3-day anxiety scores and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder scores, and postoperative 3-day breakthrough pain and adverse reaction occurrence.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was conducted using the SPSS 26.0 statistical software package. Measurement data with a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (\(\:\stackrel{-}{\text{x}}\)±s), while measurement data with a non-normal distribution were expressed as median (interquartile range) [M (Q1, Q3)]. Categorical data were described using frequency and percentage (n, %). For inter-group comparisons of normally distributed measurement data with a group design, the t-test for group design is used. For inter-group comparisons of normally distributed measurement data with repeated measurements, the repeated measures ANOVA is employed. Pairwise comparisons are conducted using the LSD method, and intra-group comparisons are performed using one-way ANOVA. For comparisons of count data, the chi-square test is used. The significance level (a) is set at 0.05, and a P-value less than 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Results

Initially, 135 cases were included in this study. Due to factors such as unclear structure leading to block failure and changes in surgical methods, 2 cases were excluded from Group C, 4 cases from Group N1, and 2 cases from Group N2. In the end, a total of 127 patients were included. There were no statistically significant differences in general data such as gender, age, ASA classification, BMI, anesthesia time, and operation time among the three groups of patients (Table 1).

Compared with Group C, the rest and activity VAS scores at each time point in Groups N1 and N2 were significantly lower 3 days after surgery (P < 0.05). The rest and activity VAS scores in all three groups initially increased and then decreased with the extension of time (Group C’s scores at time points 12 h after surgery and 24 h after surgery were significantly higher than those at time points 3 h after surgery, 6 h after surgery, and 72 h after surgery, while Groups N1 and N2’s scores at time points 12 h after surgery, 24 h after surgery, and 48 h after surgery were significantly higher than those at time points after awakening, 3 h after surgery, 6 h after surgery, and 72 h after surgery) (Table 2).

Compared with Group C, Ramsay sedation scores after awakening in Groups N1 and N2 significantly increased. The intraoperative sufentanil dosage, postoperative additional tramadol and flurbiprofen axetil dosage, and the number of cases experiencing breakthrough pain on the first and second postoperative days all significantly decreased. The time to the first postoperative ambulation was advanced, and both HADS-A scores and sleep scores on postoperative day 3 significantly decreased; There was no statistically significant difference in quadriceps muscle strength during the awakening period among the three groups of patients, and the muscle strength was above grade 4 in all cases (Tables 3, 4 and 5).

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of dizziness, nausea, and vomiting among the three groups three days post-surgery.

Discussion

Although ACLR is a minimally invasive surgery, it often leads to moderate to severe postoperative pain10, and even explosive pain. The occurrence of postoperative pain is related to factors such as preoperative ligament damage, intraoperative instrument stimulation, postoperative inflammation, and nerve root injury. Among them, surgery is the most significant factor contributing to postoperative pain. There are typically three surgical incisions in ACLR, namely the anteromedial incision, anterolateral incision, and ultramedial incision. During the procedure, a series of manipulations such as harvesting autologous tendons, establishing a tibiofemoral tunnel, fixing the graft, clearing inflammatory and edematous synovium, stimulating the joint capsule, and surrounding ligament tissues can cause harmful stimuli11, thereby inducing pain. In addition, ischemia-reperfusion injury caused by the use of tourniquet during surgery can also lead to postoperative pain12. It can be seen that the postoperative pain caused by ACLR surgery is multifaceted, with the pain area being innervated by relevant nerves, nociceptors, and pain fibers distributed throughout the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee joint13. The author’s research found that the combination of proximal adductor canal and pes anserinus tendon block can effectively alleviate postoperative pain after ACLR, with good analgesic effects, and has minimal impact on quadriceps muscle strength, promoting early postoperative functional exercise and even walking activities.

The innervation of the knee joint is relatively complex. Generally speaking, the knee joint is mainly innervated by branches of the obturator nerve, femoral nerve, tibial nerve, and common peroneal nerve. The ACB block method is categorized into proximal, mid-segment, and distal approaches. Due to the varying nerves and nerve branches present at different locations of the ACB, the range of block varies accordingly. The proximal end of the adductor canal contains sensory nerves such as the saphenous nerve, the medial femoral nerve branch of the femoral nerve, the medial femoral cutaneous nerve, and the articular branch of the obturator nerve14. Among them, there are two nerves that accompany the femoral artery and vein downwards, namely the saphenous nerve and its lateral femoral medial muscle branch. These two main branches of the femoral nerve innervate the anterior and medial parts of the knee joint. The saphenous nerve runs through the sartorius and gracilis muscles on the medial side of the knee joint, eventually distributing to the subcutaneous tissue. It emits a subpatellar branch to form the patellar plexus. The saphenous nerve primarily controls the sensation of the medial, anteromedial, and posteromedial aspects of the lower leg between the knee joint and the medial malleolus. The articular branch of the posterior branch of the obturator nerve passes through the lower part of the adductor magnus muscle and travels backward, or passes through the adductor magnus muscle and the adductor magnus tendon fissure, which is crossed by the deep femoral artery communicating branch, to the popliteal fossa. It is distributed in the knee joint capsule, cruciate ligaments, and surrounding tissues.

The pes anserinus is formed by the conjoined tendons of the sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus muscles, resembling a “goose foot” in shape. It attaches to the medial anterior border of the tibia and is the preferred autograft for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction surgery15,16. Among the three tendons, the semitendinosus is the longest and thickest, while the sartorius tendon is the shortest and unsuitable as a graft for ACL reconstruction (ACLR)17. Therefore, ACLR primarily utilizes the relatively functionally weaker gracilis and semitendinosus tendons for ACL reconstruction18,19,20. The saphenous nerve descends along the medial knee, superficial to the pes anserinus. Its infrapatellar branch courses anterior to the pes anserinus, innervating the skin of the infrapatellar region17. The pes anserinus itself is predominantly innervated by the sciatic nerve, specifically involving spinal nerve roots L5 to S2. The sartorius muscle receives innervation from the femoral nerve, with each sartorius muscle accepting 1–5 branches (most commonly 1–2 branches) from the femoral nerve. Each branch further divides into 1–7 smaller sub-branches (most frequently 3–4) before entering the muscle21. The gracilis muscle is innervated by branches from the anterior division of the obturator nerve. This nerve originates from the pubic ramus of the ischium, courses inferomedially between the adductor longus and brevis muscles, and accompanies the main vascular bundle of the gracilis to form a neurovascular bundle. It enters the posterior aspect of the sartorius muscle and tendon at the anteromedial mid-upper junction of the gracilis. The semitendinosus, a fusiform muscle innervated by the sciatic nerve, originates proximally from the ischial tuberosity alongside the semimembranosus and long head of the biceps femoris, and inserts on the medial aspect of the proximal tibia22.

The dosage of local anesthetics administered into the adductor canal is categorized into small volume (5–10 ml), medium volume (10–20 ml), and large volume (20–30 ml). However, considering the safety and effectiveness of postoperative analgesia, scholars both domestically and internationally have differing opinions on the dosage and concentration of local anesthetics used in the adductor canal. In a study conducted by Jaeger et al.23 on the assessment of the impact of volume on the diffusion of local anesthetics into the proximal femoral triangle using magnetic resonance imaging, it was found that when injecting 5, 10, 15, and 20 ml volumes of local anesthetics into the adductor canal, 0%, 58%, 50%, and 50% of the local anesthetics, respectively, diffused upward into the femoral triangle region. Based on these results, they speculated that differences in fascia may have a greater impact on drug diffusion compared to the volume of local anesthetic, especially considering that multiple fascial structures may affect the diffusion of injected drugs. Andersen et al.‘s24 anatomical study showed that 15 ml of local anesthetic is sufficient to fill the entire adductor canal, while avoiding the possibility of blocking the motor branch of the femoral nerve. A study25 found that the median effective volume of 0.5% ropivacaine ACB is 10.79 ml. Govil et al.26 believed that 10 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine is not inferior to 20 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine in terms of providing postoperative analgesia and preserving quadriceps strength. Therefore, theoretically, 0.5% ropivacaine 15 ml used for adductor canal block can effectively provide analgesia and preserve quadriceps muscle strength.

In clinical practice, it has been observed that patients undergoing ACLR surgery who received adductor canal block alone exhibited suboptimal postoperative analgesic effects. Based on the anatomical foundation that the gracilis muscle harvested from autologous tendons is innervated by the obturator nerve while the semitendinosus is innervated by the sciatic nerve, this study implemented a combined proximal adductor canal and pes anserinus tendon block in ACLR patients. The results demonstrated that the experimental group showed significantly reduced consumption of sufentanil, postoperative supplemental tramadol, and flurbiprofen axetil. Resting and movement pain scores at all time points within the postoperative 3 days were markedly lower, with mean scores below 3 points. These findings suggest that the combined proximal adductor canal and pes anserinus tendon block provides superior analgesic effects compared to isolated proximal adductor canal block. The underlying mechanism may involve the proximal adductor canal block effectively anesthetizing the saphenous nerve, branches of the vastus medialis muscle, posterior medial branches of the femoral nerve, and articular branches of the posterior obturator nerve, yet failing to block the obturator nerve innervating the gracilis muscle and the sciatic nerve supplying the semitendinosus. The pes anserinus tendon block compensates for this deficiency while additionally blocking nociceptors and pain fibers at the tendon harvest site and incision for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Furthermore, local anesthetics may diffuse along myofascial planes to peripheral nerve branches and inhibit the action of inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α on nerve endings stimulated by inflammatory factors, thereby interrupting ascending pain transmission27.

Early postoperative rehabilitation exercises for the knee joint can help alleviate muscle tension and joint stiffness, and increase the range of motion of the knee joint. However, severe postoperative pain may limit patients’ mobility, adversely affecting early recovery and prognosis28. In addition, restoring quadriceps muscle strength after surgery is a crucial aspect of early rehabilitation training following knee surgery.Adductor canal block and femoral nerve block have been proven effective in postoperative analgesia for knee surgery. The femoral nerve block has been an ideal approach for knee surgery in the past, with advantages of simple operation and good analgesic effect, However, the incidence of quadriceps muscle weakness or paralysis is relatively high after surgery, which increases the risk of falls and is not conducive to patient recovery29; The block of the adductor canal does not directly affect the main motor nerve of the femoral nerve, thus having a minimal impact on quadriceps muscle strength, which is more conducive to early rehabilitation training30. The sensory nerves in the lower limbs of the adductor canal are relatively dispersed. The injected local anesthetic diffuses slowly here, acting on numerous nerves and their branches. At the same time, due to the horizontal distribution of its motor fibers, it does not significantly affect the leg muscle tissue, effectively complementing the limitations of femoral triangle block. Compared to femoral triangle block, ACB can provide superior analgesic effects and retain more quadriceps strength31; John-Rudolph et al.32 believed that in the short term (24–48 h), ACB has a potential advantage over FNB in maintaining muscle strength. The study by Chisholm et al.33 indicated that in ACLR surgery, a single ACB can achieve similar postoperative analgesic effects as FNB, while better preserving quadriceps muscle strength. This finding was further validated in the studies by Miguel et al.34 and Minghe et al.35 on patients undergoing TKA surgery. Therefore, ACB is beneficial for early functional exercise, aligns with the concept of rapid rehabilitation, and is worthy of clinical promotion.

In this study, the quadriceps muscle strength of all patients remained largely unaffected, with muscle strength levels above grade 4. Furthermore, patients in the group receiving proximal adductor canal and pes anserinus tendon block experienced earlier postoperative mobilization. This indicates that the experimental method, involving 15 ml of ropivacaine for ultrasound-guided proximal adductor canal block, has minimal impact on quadriceps muscle strength in patients undergoing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery under knee arthroscopy. It effectively preserves quadriceps muscle strength and provides excellent postoperative analgesia, thereby facilitating early postoperative rehabilitation training and promoting better postoperative recovery. Adductor canal block mainly achieves its effect by blocking sensory signals. It contains a major sensory branch of the femoral nerve, the saphenous nerve, which innervates the anterior and inferior parts of the knee joint. The femoral triangle is connected to the entrance of the adductor canal, which limits the volume of local anesthetic and reduces the chance of drug diffusion into the femoral triangle area. Therefore, ACB has minimal impact on quadriceps muscle strength, facilitating early functional exercise, accelerating blood circulation in the knee joint area, thereby accelerating the clearance of local inflammatory factors, reducing the concentration of local inflammatory factors in the knee joint, alleviating postoperative pain caused by inflammatory factors, and promoting early recovery36,37. This is consistent with the findings of Abdallah et al.38, who showed that when different approaches were used for ACLR surgery, blocking the adductor canal at its proximal end did not affect quadriceps muscle strength but provided effective analgesia.

An increasing number of researchers are beginning to focus on the intrinsic connection between pain, anxiety, and depression, positing that they share a common biological basis39. A vicious cycle can form between pain, anxiety, and depression, which interact and exacerbate each other, undoubtedly having a detrimental impact on patients’ postoperative recovery40. The author’s research suggests that the combined block of the proximal adductor canal and the talocrural tendon has a good sedative effect, effectively alleviating postoperative anxiety in patients undergoing ACLR surgery and reducing the incidence of postoperative sleep disorders. This is of great significance for alleviating postoperative pain, reducing the occurrence of adverse reactions, and promoting rapid recovery in patients41. This conclusion aligns with the findings of Hussain et al.42, indicating that effective postoperative analgesia can facilitate patients to commence rehabilitation exercises earlier, while also enhancing their psychological well-being and sleep quality, thereby significantly promoting postoperative recovery.

In summary, the observation results of this study indicate that the application of 0.5% ropivacaine in a dosage of 15 ml each, combined with ultrasound-guided proximal adductor canal and talocrural tendon block, for daytime knee arthroscopy anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery, can effectively provide good analgesic effects, And it basically does not affect the quadriceps muscle strength of the affected limb during the postoperative recovery period, promotes early postoperative ambulation, and reduces the incidence of postoperative anxiety and sleep disorders, which is beneficial for early postoperative recovery. There was no significant difference in the observed indicators between the experimental group, which used 5 mg dexamethasone as an adjuvant added to local anesthetic, and the control group that did not use it, 3 days after surgery.However, due to the relatively small sample size of this study, the aforementioned conclusions require further verification through more high-quality, large-sample studies.

Conclusion

Ultrasound-guided proximal adductor canal and pes anserinus tendon block (15 ml of 0.5% ropivacaine each) can effectively alleviate pain 3 days after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery under knee arthroscopy, with good analgesic effects, and has minimal impact on quadriceps muscle strength after awakening, promoting early postoperative ambulation; at the same time, this blocking method can reduce the occurrence of postoperative anxiety and sleep disorders.

Limitations of the research

Given the practical constraints in clinical implementation, this study adopted a randomized single-blind design to eliminate patient bias, though this approach may introduce potential assessor bias. While we have rigorously implemented randomization protocols and standardized operational procedures to minimize such bias, we explicitly acknowledge in the revised manuscript that future studies should prioritize double-blind methodologies to further strengthen result credibility.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACLR:

-

Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- ACL:

-

Anterior cruciate ligament

- FNB:

-

Femoral nerve block

- ACB:

-

Adductor canal block

- ASA:

-

American society of anesthesiologists

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

- ACA:

-

Adductor canal aponeurosis

- SM:

-

Sartorius muscle

- PAC:

-

Proximal adductor canal

- SFA:

-

Superficial femoral artery

- ALM:

-

Adductor longus muscle

- VM:

-

Vastus medialis

- SN:

-

Saphenous nerve

- FA:

-

Femoral vein

- RP:

-

Ropivacaine

- ST:

-

Sartorius tendon

- GT:

-

Gracilis tendon

- SMT:

-

Semitendinous muscle tendon

References

Mouarbes, D. et al. Anterior cruciate ligamentreconstruction: A systematic review and Meta-analysis of outcomes for quadriceps tendon autograft versus Bone-Patellar tendon-Bone and Hamstring-Tendon autografts[J]. Am. J. Sports Med. 47 (14), 3531–3540 (2019).

Nuelle, C. W., Balldin, B. C. & Slone, H. S. All-Inside anterior cruciate ligament Reconstruction[J]. Arthroscopy 38 (8), 2368–2369 (2022).

Hughes, L. et al. Examination of the comfort Andpain experienced with blood flow restriction training during post-surgery rehabilitation of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction patients: A UKNational health service trial[J]. Phys. Ther. Sport. 39 (2), 90–98 (2019).

Jenkins, S. M. et al. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament injury: review of current literature and Recommendations[J]. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 15 (3), 170–179 (2022).

Glattke, K. E., Tummala, S. V. & Chhabra, A. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction recovery and rehabilitation: A systematic Review[J]. JBone Joint Surg. Am. 104 (8), 739–754 (2022).

Khalladi, K. et al. Sleep and psychological factors are associated with meeting discharge criteria to return to sport following ACL reconstruction in athletes[J]. Biol. Sport. 38 (3), 305–313 (2021).

Frazer, A. R. et al. Quadriceps and hamstring strength in adolescents 6 months after ACL reconstruction with femoral nerve block, adductor Canal block, or no nerve Block[J]. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 9 (7), 23259671211017516 (2021).

Oshima, T. et al. Ultrasound-guided adductor canal block is superior to femoral nerve block for earlypostoperativepain relief after single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring autograft[J]. J Med Ultrason 2023; 50(3): 433–439. (2001).

Weibel, S. et al. Drugs for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting in adults aftergeneral anaesthesia: a network meta-analysis[J]. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10 (10), CD012859 (2020).

Hurley, E. T., Danilkowicz, R. M. & Toth, A. P. Editorial commentary: postoperative pain management after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction can minimize opioid use and allow early Rehabilitation[J]. Arthroscopy 39 (5), 1296–1298 (2023).

Joel,Katz. Pre-emptive analgesia: importance of timing[J].Can-adian. J. Anesth. 48 (2), 105–114 (2001).

Kamath, K., Kamath, S. U. & Tejaswi, P. Incidence and factors influencingtourniquet pain[J]. Chin. J. Traumatol. 24 (5), 291–294 (2021).

Hong, A. J. et al. Neurological structures and mediators of pain sensation in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction[J]. Ann. Anat. 22 (5), 28–32 (2019).

Kim, D. H. et al. Interscalene brachial plexus block with liposomal bupivacaine versus standard bupivacainewith perineural dexamethasone: A noninferiority Trial[J]. Anesthesiology 136 (3), 434–447 (2022).

Ridley, W. E., Xiang, H., Han, J. & Ridley, L. J. Pes Anserinus: normal anatomy[J]. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 62 (Suppl 1), 148 (2018).

Lee, J. H. et al. Pes Anserinus and Anserine Bursa: anatomical study[J]. Anat. Cell. Biol. 47 (2), 127–131 (2014).

Zhong, S. et al. The anatomical and imaging study of Pes Anserinus and its clinical application[J]. Med. (Baltim). 97 (15), e0352 (2018).

Freedman, K. B. et al. Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a metaanalysis comparing patellar tendon and hamstring tendon autografts[J]. Am. J. Sports Med. 31, 2–11 (2003).

Roujeau, T., Decq, P. & Lefaucher, J. P. Surface EMG recording of heteronymous reflex excitation of semitendinosus motoneurones by group II afferents[J]. Clin. Neurophysiol. 115, 1313–1319 (2004).

Forssblad, M. et al. ACL reconstruction: patellar tendon versus hamstring grafts—economical aspects[J]. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 14, 536–541 (2006).

Shuming Xiong, L. et al. Vascular and neural supply of sartorius muscle [J]. J. Anat. 14 (01), 32–36 (1983).

Curtis, B. R. et al. Pes Anserinus: anatomy and pathology of native and harvested Tendons[J]. Am. J. Roentgenlogy. 213, 1107–1116 (2019).

Jaeger, H. et al. Adductor Canal block versus femoral nerve block for analgesia after total kneearthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind study[J]. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 38 (6), 526–532 (2013).

Andersen, H. L., Andersen, S. L. & Tranum-Jensen, J. The spread of injectate during saphenous nerve block at the adductor Canal: acadaver study[J]. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 59 (2), 238–245 (2015).

Wang, C. et al. Locating adductor Canal and quantifying the median effective volume of ropivacaine for adductor Canal block by Ultrasound[J]. J. Coll. Physicians SurgPak. 31 (10), 1143–1147 (2021).

Govil, N. et al. Comparison of two different volumes of 0.5%, ropivacaine used in ultraso und-guided adductor Canal block after knee arthroplast y: A randomized, blinded, controlled noninferiority tr ial[J]. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 38 (1), 84–90 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. Application of Dexmedetomidine combined with ropivacaine in axillary brachial plexus block in children and its effect on inflammatory factors. Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand). 66 (5), 73–79 (2020).

Li Yang, L. & Jinfeng, L. Effect of ultrasound-guided continuous adductor Canal block combined with sciatic nerve block on postoperative pain relief in elderly patients undergoing knee arthroplasty [J]. J. Clin. Anesthesiology. 35 (9), 846–849 (2019).

Dixit, A., Prakash, R. & Yadav, A. S. Et Alc. Comparative study of adductorcanal block and femoral nerve block for postoperative analgesia after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament tear repair surgeries. Cureus 14 (4), e24007 (2022).

Zhang Jialei, G. & Min, W. The impact of ultrasound-guided continuous adductor Canal block combined with periarticular infiltration analgesia on postoperative immune cells in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty [J]. Chin. J. Clin. Practitioners. 13 (12), 898–901 (2019).

Wang, C. G. et al. Comparison of adductorcanalblock and femoral triangle block for total knee Arthroplasty[J]. Clin. J. Pain. 36 (7), 558–561 (2020).

Smith, J. H. et al. Adductor Canal versus femoral nerve block after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review of level I randomized controlled trials comparing early postoperative pain, opioid requirements, and quadriceps Strength[J]. Arthroscopy 36 (7), 1973–1980 (2020).

Chisholm, M. F. et al. Postoperative analgesia with saphenous block appears equivalent to femoral nerve block in ACL reconstruction [J]. HSS J. 10 (3), 245–251 (2014).

Miguel, M. et al. Single-injection nerve blocks for total knee arthroplasty: femoral nerve block versus femoral triangle block versus adductor Canal block-a randomized controlled double-blinded trial[J]. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 143 (11), 6763–6771 (2023).

Tan, M. et al. Comparison of analgesic effects of continuous femoral nerve block, femoral triangle block, and adductorblock after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized clinical Trial[J]. Clin. J. Pain. 40 (6), 373–382 (2024).

Ambrosoli, A. L. et al. Postoperative analgesiaand early functional recovery after day-case anterior cruciate ligamentreconstruction: a randomized trial on local anesthetic delivery methodsfor continuous infusion adductor Canal block[J]. Minerva Anestesiol. 85 (9), 962–970 (2019).

Lei, Y. T. et al. Benefits of early ambulation within24 h after total knee arthroplasty: a multicenter retrospective cohort study in China[J]. Mil Med. Res. 8 (1), 17 (2021).

Abdallah, F. W. et al. Opioid- and motorsparingwith proximal, Mid-, and distal locations for adductor canalblock in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized clinical Trial[J]. Anesthesiology. 131 (3), 619–629 (2019).

Varış, O. & Peker, G. Effects of preoperative anxiety level on pain leveland joint functions after total knee arthroplasty[J]. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 20787 (2023).

Xu, J. et al. The association between anxiety, depression, and locus of control with patient outcomes following total knee Arthroplasty[J]. J. Arthroplasty. 35 (3), 720–724 (2020).

Elliott, D. et al. Patient comfort in theintensivecare unit: a multicentre, binational Po int prevalence study of analgesia,sedation and deliriu mmanagement[J]. Crit. Care Resusc. 15 (3), 213–221 (2013).

Hussain, N. et al. Network meta-analysisof the analgesic effectiveness of regional anaesthesia techniques for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction[J]. Anaesthesia 78 (2), 207–224 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was coordinated by the Department of Anaesthesiology and Department of Medical Statistics, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Guangxi, China.

Funding

This study was funded by Guangxi Medical and health appropriate technology development and promotion Foundation (S2020021); Self-funded scientific research project of the Health Commission of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region(Z-A20240419).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dan Zhang: Project design, Instruct the experiment, Writing-original draft.Xin Wang: Experiment research, Project design, Statistics and analysis of data.GuiLi Huang, Lanying Wu, Yuhua He and Yating Huang: Experiment research.Guangying Zhang: Project design, Instruct the experiment, Writing-review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, D., Wang, X., Huang, G. et al. Ultrasound guided proximal adductor canal and pes anserinus blocks improve early recovery after arthroscopic ACL reconstruction. Sci Rep 15, 10236 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94343-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94343-0