Abstract

Several studies reported the immediate positive effect of core stability exercises on postural balance in different populations. However, other studies documented no significant immediate effect on balance performance. It remains unclear whether a single session of core stability exercises can improve postural balance in soccer players with groin pain (GP). This study aimed to investigate the acute effect of core stability exercises on this parameter in these players. A total of 15 male soccer players with GP carried out a single session of 15 core stability exercises lasting 40 min. Static (force platform) and dynamic (Y-Balance test) postural balance outcomes were assessed 4 times: just before (T0), post-1 min (T1 min), post-30 min (T30 min), and post-24 h (T24h) of the core exercises. Soccer players with GP showed significantly improved (p < 0.05 − 0.001) static (bipedal; firm surface-eyes closed, injured limb; eyes opened and closed) and dynamic (injured and non-injured limbs) postural balance at T24h, T30min, T1min compared to T0. Additionally, better dynamic postural balance measures on injured limb were observed at T24h and T30min when compared to T1min. Findings revealed that a single session of core stability exercises acutely improved static and dynamic postural balance in soccer players with GP 1 min and 30 min after exercises, extending over 24 h. Therefore, trainers and coaches could consider integrating core exercises into warm-up programs for soccer players with GP who need to maintain balance during training and competitive events. Given that warm-up sessions typically last 25–30 min and the core exercises in this study require 40 min, players should complete an extra 25 min of core exercises before joining their teammates for the scheduled pre-warm-up and warm-up sessions. The remaining 15 min should be incorporated into the pre-warm-up session. Additionally, it is recommended to include these exercises into pre-event routines to optimize preparation time and balance performance during training sessions and competitive matches in soccer players with GP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Groin pain (GP) is one of the most common lower limb injuries in men’s soccer1. This practice requires sudden acceleration and deceleration, rapid changes of direction, jumping, and landing to win and possess the ball2. If the lower limb is moving on an unstable core (lumbo-pelvic-hip complex), then structures around the groin may be stressed unduly and consequently pathologies can result3. Thus, core training is crucial for soccer practice4. GP is categorized into three major groups: clinical entities, hip-related and other causes of GP5, with adductor-related GP being the most frequently occurring clinical entity6,7. It has been documented that soccer players with GP had postural balance disorders compared to controls8,9,10,11. These disorders were associated with poor core stability suggesting altered trunk muscle function in these players12. Improving postural balance in soccer players helps to optimize their performance and soccer technical skills13. Not surprisingly, its deterioration is associated with limited physical performance14. Additionally, postural balance disorders are reported to be the cause of subsequent lower limb injuries15. Hence, soccer players with non-time loss GP may present poor physical performances and a risk to sustain injuries subsequently to GP due to postural balance deficiencies8,9. So, clinicians and coaches should consider balance training while designing rehabilitation strategies for soccer player with GP. Such strategies could prevent potential consequences associated with postural balance impairments.

Balance training is prescribed to prevent and treat injuries associated with poor postural balance, and part of this is core stability exercises16. These exercises activate specific motor patterns in the trunk muscles, promoting trunk stability17. Core stability refers to the ability to control the position and movement of the trunk in relation to the pelvis for optimal force production and transfer to the end segments18. Several studies reported the immediate positive effect of core stability exercises on static postural balance in different populations19,20,21. Indeed, it is thought that the continuous muscle contraction during core stability exercise causes temporary muscle stiffness, which improves the postural balance function20. Besides, it has been suggested that a high density of spindle receptors in some spinal muscles could benefit from core stability exercises, leading to proprioceptive improvements19. Additionally, core stability exercises may provide improvements in joint range of motion and functional movement capacity in soccer players22. However, other studies documented no significant immediate effect on static and dynamic balance performances23,24. Numerous rehabilitation programs including core stability exercises have been proposed in clinical practice to manage GP and proved its efficiency25,26,27.

A recent study reported that 12-week of core training improves dynamic postural balance in soccer players with groin pain28. However, it is still unknown whether a single bout of core stability exercises would acutely improve postural balance in soccer players with GP. Examining the acute effect of core stability exercises on postural balance will help to elucidate their usefulness as part of warm-up programs for these players who are required to control balance during training sessions and competitive meets. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the acute effect of core stability exercises on postural balance in soccer players with GP. We hypothesized that a single bout of core stability exercise would acutely improve balance performance in these players.

Methods

Study design

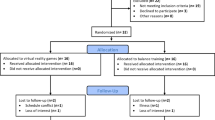

This was pre-post-repetitive measurement study. It was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee of the High Institute of Nursing, University of Sfax (approval number: 0206/2019). All the included participants were informed in detail about the procedures and agreed to participate voluntarily, following which a consent form was signed.

Considering that there’s a lack of published data in the literature, an a priori sample size estimate was calculated with a large effect size (0.4)29, an alpha of 0.05, and a power (1−β) of 0.95. Using G*Power software, 15 participants were required to compare postural balance between pre- and post-core stability exercises.

Participants

A total of 15 male soccer players with GP that belonged to six second division soccer teams took part in this study. These players were recruited through direct verbal advertisements in sports medicine centres and physical rehabilitation clinics that provide health care to soccer clubs. Qualified sports medicine physicians working in the sports medicine center diagnosed and referred the cases. Injured players were included if they experienced a unilateral non-time-loss adductor-related GP, for at least 2 months. Diagnosis of this entity was based on Doha agreement regarding the definition and classification of GP5. In addition, cases were eligible for inclusion if they were not receiving rehabilitation sessions or medication for the treatment of GP. Soccer players with chronic urinary tract disorders or prostatitis, pelvic bone fracture, sudden onset GP, inguinal or femoral hernia, hip joint disease, nerve entrapments in the groin area, back pain and prior groin or hip surgery and sacroiliac joint pathology were excluded. Besides, those with musculoskeletal, visual, vestibular pathologies or injury history during the past year were excluded. In fact, each soccer player included, being treated in sports medicine centers and physical rehabilitation clinics, has his own medical file, which includes the results of several clinical examinations. These results ensure that the cases included do not suffer from any pathologies, as indicated in the exclusion criteria. Participants eligible for inclusion completed the Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS) questionnaire to quantify groin problems at baseline30,31.

Procedures

Two days of experiments were conducted. Indeed, participants underwent static and dynamic postural balance measurements 4 times: just before (T0), post-1 min (T1 min), post-30 min (T30 min), and post-24 h (T24 h) of the protocol. To minimize circadian variation, each participant was examined at the same time of day and under the same environmental conditions (laboratory temperature at 24 °C). All the measurements were performed by an independent investigator who was unaware of the study’s aim and was blinded to the measurement time points. This investigator, using a chronometer, controlled the timing of the assessments. To ensure consistency in measurement timing, each participant was scheduled individually, as it would not have been possible to maintain identical testing times if multiple participants were present simultaneously. Upon arrival at the laboratory, participants first underwent anthropometric measurements, and data related to playing and match exposures, injured and dominant limbs were collected. Then, postural balance assessments were performed immediately before the core exercises, followed by re-testing at T1 min, T30 min, and T24 h post-exercises. Participants were told not to exercise the day before and the days of experiment so as not to affect the postural balance outcomes. Besides, they were asked to consume their last (caffeine-free) meal at least 3 h before the scheduled experiment time.

Protocol

The protocol used for the core stability exercises was similar to that described by Szafraniec et al.21, which contained 15 core exercises and lasted 40 min. These exercises are detailed in Table 1. Another experienced physiotherapist supervised the participants while performing the core exercises, and none of them experienced pain or fatigue during or after the session. Indeed, participants were monitored for outward signs of fatigue, such as regression of exercise form, changes in ventilation and verbal cues.

Static postural balance

Static postural balance was evaluated using a force platform (Techno Concept®, PostureWin©, Cereste, France; 12-bit A/D conversion, frequency 40 Hz) that records the center of pressure (CoP) displacements. Postural balance was assessed during unipedal (injured limb and non-injured limb) and bipedal postures. During assessments, postural measurements were collected in 2 visual conditions (eyes opened [EO] and closed [EC]) on 2 surfaces (firm surface and foam one). The foam surface was not considered when assessing postural balance during the unipedal posture, as the participants were not able to maintain their balance on this surface. During the bipedal posture, participants were barefoot, separated by an angle of 30° with their heels placed 5 cm apart. Whereas, during the unipedal one, they were barefoot on one limb (injured limb / non-injured limb) while the other limb was flexed to 45° at the hip and knee. For all conditions, three trials (each trial lasted 25.6s) were performed, in a random order, with 1 min rest between trials to avoid fatigue and learning effects. The average value of the three trials was considered for analysis. The mean CoP velocity (CoPVm), calculated by dividing the CoP excursion by the trial time32, was considered in our study to analyze postural balance outcomes. It has been reported that, in stable and unstable conditions, CoPVm showed good results in relative intrasession reliability and is the traditional measure that best ranks individuals in balance tasks33. It also reflects the efficiency of the postural control system (the smaller the velocity, the better the postural balance performance) while characterizing the net neuromuscular activity required to maintain balance32.

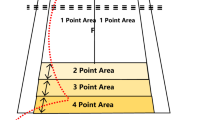

Dynamic postural balance

The Y-Balance test (Y-BT) was used to measure dynamic postural balance in the anterior (ANT), posteromedial (PM) and posterolateral (PL) directions34. While standing on one limb (injured limb / non-injured limb), participants were instructed to reach as far as possible in each of the three directions. The reached distance was measured in centimeters from the center of the grid to the point the participant successfully reached in the specified direction. Participants completed the four recommended practice trials, followed by three measured trials in each direction35. The length of the participants’ lower limbs was measured bilaterally with a non-stretchable tape. The greatest distance reached in each direction was normalized to the lower limb length. Besides, a normalized composite score (CS) was calculated for each limb36.

Statistical analysis

Data normality were verified with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Values were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and 25–75% interquartile range (HAGOS). Two separate two-way ANOVA, for repeated measures, was used to assess the effect of times (baseline, 1 min, 30 min and 24 h) and vision (EO, EC) factors on the CoPvm values during the bipedal (on firm and foam surfaces) and unipedal postures. In addition, a one-way ANOVA, for repeated measures, was performed to examine the effect of times on Y-BT results. Effect sizes are indicated using partial eta squared (small effect: 0.01 < ηp2 < 0.06; medium effect: 0.06 < ηp2 < 0.14; large effect: ηp2 > 0.14)37,38. For each significant main factor and interaction, a post-hoc Bonferroni test was performed. For all statistical analyses, an alpha level was set at 0.05, and data analysis was performed using the software package IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 26.0, 64 bits, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Participants

All the participants (n = 15) attended the two experiment days, and no drop out was registered. The participants’ characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Static postural balance

On firm surface with bipedal posture, results showed significant effects of vision (F = 41.64, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.74) and times (F = 4.68, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.54) and a times*vision interaction (F = 5.26, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.56) on CoPVm values. In EC, there were statistically significant lower CoPVm values at T24h (p < 0.01, 2.31 [95% CI: 0.61–4.01]), T30min (p < 0.05, 2.55 [95% CI: 0.11–4.99], T1min (p < 0.05, 1.95 [95% CI: 0.29–3.60]) compared to T0. However, in EO, no significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed at T24h (0.47 [95% CI: -0.66-1.62]), T30min (0.27 [95% CI: -0.93-1.48]), T1min (0.11 [95% CI: -0.84-1.07]) compared to T0 (Table 3).

On foam surface with bipedal posture, results showed a significant effect of vision (F = 29.68, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.68) on CoPVm values. However, no significant effect (p > 0.05) of times (F = 2.87, ηp2 = 0.41) and no times*vision interaction (F = 1.00, ηp2 = 0.20) on this parameter were found.

On the injured limb, there were significant effects of vision (F = 333.11, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.96) and times (F = 14.82, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.78) and a times*vision interaction (F = 4.25, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.51) on CoPVm values. In both EO and EC, there were statistically significant lower CoPVm values at T24h (EO: p < 0.05, 7.08 [95% CI: 1.06–13.09]; EC: p < 0.01, 15.95 [95% CI: 6.73–25.16]), T30min (EO: p < 0.01, 9.68 [95% CI: 2.97–16.40]; EC: p < 0.01, 13.12 [95% CI: 4.80-21.43]), T1min (EO: p < 0.01, 6.26 [95% CI: 1.46–11.06]; EC: p < 0.01, 11.65 [95% CI: 3.74–19.56]) compared to T0 (Table 4).

On the non-injured limb, results showed a significant effect of vision (F = 218.38, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.94) on CoPVm values. However, no significant effect (p > 0.05) of times (F = 2.61, ηp2 = 0.39) and no times*vision interaction (F = 1.35, ηp2 = 0.25) were found for this parameter (Table 4).

Dynamic postural balance

On the injured limb, results showed a significant effect of times (ANT: F = 11.16, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.73; PM: F = 13.89, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.77; PL: F = 17.96, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.81; CS: F = 18.85, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.82) on Y-BT outcomes in our soccer players. Within times comparison revealed these outcomes significantly improved at T24h (ANT: p < 0.001, 9.73 [95% CI: 4.65–14.82]; PM: p < 0.001, 13.87 [95% CI: 6.65–21.09]; PL: p < 0.001, 12.05 [95% CI: 6.71–17.39]; CS: p < 0.001, 11.88 [95% CI: 7.31–16.46]), T30min (ANT: p < 0.01, 7.79 [95% CI: 2.11–13.48]; PM: p < 0.001, 11.31 [95% CI: 5.95–16.66]; PL: p < 0.01, 10.45 [95% CI: 3.89-17.00], CS: p < 0.001, 9.85 [95% CI: 5.88–13.82]), T1min (ANT: p < 0.05, 5.42 [95% CI: 0.64–10.21]; PM: p < 0.001, 5.52 [95% CI: 2.43–8.61]; PL: p < 0.01, 7.29 [95% CI: 2.86–11.71]; CS: p < 0.001, 6.08 [95% CI: 3.48–8.67]) compared to T0. Besides, Y-BT data were significantly better at T24h (ANT: p < 0.01, 4.30 [95% CI: 1.22–7.39]; PM: p < 0.01, 8.35 [95% CI: 2.60–14.10]; PL: p < 0.05, 4.76 [95% CI: 1.81–7.70]; CS: p < 0.001, 5.80 [95% CI: 2.81–8.79]) and at T30min (ANT: p < 0.05, 2.37 [95% CI: 0.33–4.41]; PM: p < 0.05, 5.78 [95% CI: 1.22–10.34]; PL: p < 0.05, 3.15 [95% CI: 0.22–6.09]; CS: p < 0.01, 3.77 [95% CI: 1.52–6.01]) compared to T1min (Table 4).

On the non-injured limb, results showed a significant effect of times factor (ANT: F = 8.71, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.68; PM: F = 9.08, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.69; PL: F = 3.66, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.47; CS: F = 10.27, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.72) on Y-BT outcomes in our soccer players. Within times comparison revealed that these outcomes significantly improved at T24h (ANT: p < 0.01, 4.79 [95% CI: 1.36–8.21]; PM: p < 0.01, 8.73 [95% CI: 3.28–13.65]; PL: p < 0.05, 8.24 [95% CI: 0.18–16.30]; CS: p < 0.001, 7.25 [95% CI: 3.38–11.12]), T30min (ANT: p < 0.01, 5.20 [95% CI: 1.56–8.83]; PM: p < 0.01, 8.12 [95% CI: 1.89–14.35]; PL: p < 0.05, 8.19 [95% CI: 1.03–15.36], CS: p < 0.01, 7.17 [95% CI: 2.83–11.51]), T1min (ANT: p < 0.001, 3.45 [95% CI: 0.97–5.94]; PM: p < 0.01, 5.35 [95% CI: 1.54–9.15]; PL: p < 0.05, 6.63 [95% CI: 0.17–13.09]; CS: p < 0.001, 5.14 [95% CI: 2.28-8.00]) compared to T0 (Table 4).

Discussion

The objective of the current study was to investigate the acute effect of a single bout of core stability exercises on postural balance in soccer players with GP. In line with our hypothesis, the major results showed that a single session of core stability exercises improved static (bipedal; Firm-EC, injured limb; EO-EC conditions) and dynamic postural balance (injured and non-injured limb) at T24h, T30min, T1min compared to T0. In addition, better dynamic postural balance measures on injured limb were observed at T24h and T30min when compared to T1min.

Generally, our results revealed that a single session of core stability exercises improved static and dynamic postural balance in soccer players with GP, 1 min and 30 min after exercise, extending over 24 h. To our knowledge, no data are available on the acute effect of core exercises on the postural balance in these players. However, some studies in other populations supported our results showing postural balance improvements following a single session of core exercises19,20,21. There are potential mechanisms that could contribute to the acute motor control benefits of core stability exercises. Indeed, the core is at the center of almost all kinetic chains, and it represents a kind of foundation for movements18. In the case of an undisturbed recruitment of the deep muscles of the core, they are activated at the moment before the planned locomotion activity, creating the appropriate conditions in the form of a stable body posture39. The applied exercises intensively stimulated abdominal, erector spinae and gluteal muscles, which are the main stabilizers of the core, and are responsible for controlling pelvis and trunk positioning40. It is thought that the continuous muscle contraction during exercise causes temporary muscle stiffness, which improves the postural balance function20. Besides, it has been suggested that a high density of spindle receptors in some spinal muscles could benefit from core stability exercises, leading to proprioceptive improvements19. Thus, a potential acute improvement in proprioceptive acuity may occur following the core stability session. So, if performing core stability exercises acutely facilitates proprioceptive control of intersegmental movements between the core and lower extremities, this should indeed lead to better postural balance19. Enhanced proprioceptive acuity contributes to better joint stability, thus ensuring positive stimulus-response synchronization, which helps prevent injuries41,42. By improving proprioception, athletes can control their movements, maintain balance, and execute precise motor skills required in various sports disciplines43. Some authors suggested that developing postural balance and proprioceptive functions through exercise can enhance joint stability, not only for sedentary individuals but also for athletes44.

Additionally, the core exercises applied in the current study may acutely improve general core awareness (i.e., provide immediate cues to focus on trunk movement and control), which could lead to ameliorations in postural balance19.

Our results showed that the improvement in dynamic postural balance on injured limb was better at T24h and T30min compared with T1min. This result was only observed on injured limb, so it may be that the lower values on injured limb compared with non-injured one leave more room for improvement in postural balance. According to our results, postural balance improvements in post-core exercises were not observed in all static conditions, particularly with bipedal posture on a foam surface. This postural condition is too difficult, and as soccer players showed previously postural balance deficiencies in this condition8, the single session of core exercises may be not sufficient to significantly improve postural balance when standing on this surface.

Results showed a significant improvement in postural balance performance in these players, extending over 24 h. Therefore, trainers, coaches, and physical therapists could consider integrating core exercises into warm-up programs for soccer players with GP who need to maintain balance during training and competitive events. To align with the approach used by sports coaches and trainers, the integration of core exercises into the warm-up routine should be structured effectively. Given that warm-up sessions typically last 25–30 min and the core exercises in this study require 40 min, players should complete an extra 25 min of core exercises before joining their teammates for the scheduled pre-warm-up and warm-up sessions. The remaining 15 min should be incorporated into the pre-warm-up session. This recommendation is supported by our finding that postural balance improvements were more pronounced 30 min post-exercises. Such a delay indicates that core exercises require time to produce better effects on postural balance. This could enhance players’ stability following the pre-warm-up, allowing them to be optimally prepared for matches or training sessions. Besides, engaging in these exercises the day prior these events could further enhance postural balance on the subsequent day. Therefore, it is recommended to incorporate these exercises into pre-event routines to optimize preparation time and balance performance during training sessions and competitive matches in soccer players with GP.

Some limitations of this study can be mentioned. Due to recruitment difficulties, the number of participants was too low to allocate them randomly in an experimental and a control group. The lack of a control group limits our ability to rule out the possibility that our positive outcomes were confounded by the potential learning effect following four times of testing. Future randomized clinical trials, with larger sample size, should be very useful for evaluating the efficacy of a single bout of core exercises on postural balance in soccer players with GP. Besides, it is interesting to track the effect of a single session over time (e.g. after one week). In addition, electromyography estimates of muscle activation could contribute to a better explanation of the results.

Conclusion

The current study indicated that a single session of core stability exercises improved static and dynamic postural balance in soccer players with GP 1 and 30 min after exercise, extending over 24 h. Consequently, it is recommended that these players perform 25 min of core exercises before joining their teammates for the scheduled pre-warm-up and warm-up sessions, with the remaining 15 min integrated into the pre-warm-up. Additionally, performing these exercises the day before training sessions and competitive matches may further enhance postural balance the following day.

Practical implications

-

Core exercises acutely improved static postural balance in soccer players with groin pain.

-

Dynamic postural balance also showed improvements after a single session of core exercises.

-

It is recommended to incorporate these exercises 25 min before the scheduled pre-warm-up and warm-up, with the remaining 15 min in the pre-warm-up.

-

Including them in pre-event routines optimizes preparation time and postural balance for training and matches the next day.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Werner, J., Hägglund, M., Ekstrand, J. & Waldén, M. Hip and groin time-loss injuries decreased slightly but injury burden remained constant in Men’s professional football: The 15-year prospective UEFA elite club injury study. Br. J. Sports Med. 53, 539–546 (2019).

Soylu, Y., Ramazanoglu, F., Arslan, E. & Clemente, F. M. Effects of mental fatigue on the psychophysiological responses, kinematic profiles, and technical performance in different small-sided soccer games. Biol. Sport. 39, 965–972 (2022).

Willson, J. D., Dougherty, C. P., Ireland, M. L. & Davis, I. M. Core stability and its relationship to lower extremity function and injury. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 13, 316–325 (2005).

Luo, S. et al. Effect of core training on skill performance among athletes: A systematic review. Front. Physiol. 13, 915259 (2022).

Weir, A. et al. Doha agreement meeting on terminology and definitions in groin pain in athletes. Br. J. Sports Med. 49, 768–774 (2015).

Mosler, A. B. et al. Epidemiology of time loss groin injuries in a Men’s professional football league: A 2-year prospective study of 17 clubs and 606 players. Br. J. Sports Med. 52, 292–297 (2018).

Dupré, T., Tryba, J. & Potthast, W. Muscle activity of cutting manoeuvres and soccer inside passing suggests an increased groin injury risk during these movements. Sci. Rep. 11, 7223 (2021).

Chaari, F. et al. Postural balance impairment in Tunisian second division soccer players with groin pain: A case-control study. Phys. Ther. Sport 51, (2021).

Chaari, F. et al. Postural balance asymmetry and subsequent noncontact lower extremity musculoskeletal injuries among Tunisian soccer players with groin pain: A prospective case control study. Gait Posture. 98, 134–140 (2022).

Linek, P., Booysen, N., Sikora, D. & Stokes, M. Functional movement screen and Y balance tests in adolescent footballers with hip/groin symptoms. Phys. Ther. Sport Off J. Assoc. Chart. Physiother Sports Med. 39, 99–106 (2019).

Pålsson, A., Kostogiannis, I. & Ageberg, E. Physical impairments in longstanding hip and groin pain: Cross-sectional comparison of patients with hip-related pain or non-hip-related groin pain and healthy controls. Phys. Ther. Sport Off J. Assoc. Chart. Physiother Sports Med. 52, 224–233 (2021).

Chaari, F. et al. Core stability is associated with dynamic postural balance in soccer players experiencing groin pain without time-loss. J. Orthop. 53, 1–6 (2024).

Bekris, E. et al. Proprioception and balance training can improve amateur soccer players’ technical skills. J. Phys. Educ. Sport. 12, 81–89 (2012).

Zemková, E. Sport-specific balance. Sports Med. 44, 579–590 (2014).

Paterno, M. V. et al. Biomechanical measures during landing and postural stability predict second anterior cruciate ligament injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport. Am. J. Sports Med. 38, 1968–1978 (2010).

Ferreira, R. M., Martins, P. N., Pimenta, N. & Gonçalves, R. S. Measuring evidence-based practice in physical therapy: A mix-methods study. PeerJ 10, e12666 (2022).

Kavcic, N., Grenier, S. & McGill, S. M. Quantifying tissue loads and spine stability while performing commonly prescribed low back stabilization exercises. Spine 29, 2319–2329 (2004).

Kibler, W. B., Press, J. & Sciascia, A. The role of core stability in athletic function. Sports Med. 36, 189–198 (2006).

Kaji, A., Sasagawa, S., Kubo, T. & Kanehisa, H. Transient effect of core stability exercises on postural sway during quiet standing. J. Strength. Cond Res. 24, 382–388 (2010).

Shin, H. J., Jung, J. H., Kim, S. H., Hahm, S. C. & Cho, H. Y. A comparison of the transient effect of complex and core stability exercises on static balance ability and muscle activation during static standing in healthy male adults. Healthc. Basel Switz. 8, 375 (2020).

Szafraniec, R., Barańska, J. & Kuczyński, M. Acute effects of core stability exercises on balance control. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 20, 145–151 (2018).

Yilmaz, O. Core training and motion capacity: A study on joint range in amateur soccer. Turk. J. Kinesiol. 9, 287–292 (2023).

Lee, J. B. & Brown, S. H. M. Time course of the acute effects of core stabilisation exercise on seated postural control. Sports Biomech. 17, 494–501 (2018).

de Rogério, M. et al. Acute effect of core stability and sensory-motor exercises on postural control during sitting and standing positions in young adults. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 28, 98–103 (2021).

Hölmich, P. et al. Effectiveness of active physical training as treatment for long-standing adductor-related groin pain in athletes: Randomised trial. Lancet 353, 439–443 (1999).

Weir, A. et al. Short and mid-term results of a comprehensive treatment program for longstanding adductor-related groin pain in athletes: A case series. Phys. Ther. Sport. 11, 99–103 (2010).

Yousefzadeh, A., Shadmehr, A., Olyaei, G. R., Naseri, N. & Khazaeipour, Z. The effect of therapeutic exercise on long-standing adductor-related groin pain in athletes: Modified Hölmich protocol. Rehabil. Res. Pract. 8146819 (2018).

Chaari, F., Boyas, S., Rebai, H., Rahmani, A. & Sahli, S. Effectiveness of 12-Week core stability training on postural balance in soccer players with groin pain: A single-blind randomized controlled pilot study. Sports Health. https://doi.org/10.1177/19417381241259988 (2024).

King, M. G. et al. Sub-elite football players with Hip-Related groin pain and a positive flexion, adduction, and internal rotation test exhibit distinct biomechanical differences compared with the asymptomatic side. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 48, 584–593 (2018).

Thorborg, K., Hölmich, P., Christensen, R., Petersen, J. & Roos, E. M. The Copenhagen hip and groin outcome score (HAGOS): Development and validation according to the COSMIN checklist. Br. J. Sports Med. 45, 478–491 (2011).

Schoffl, J., Dooley, K., Miller, P., Miller, J. & Snodgrass, S. J. Factors associated with hip and groin pain in elite youth football players: A cohort study. Sports Med. Open. 7, 97 (2021).

Paillard, T. & Noé, F. Techniques and methods for testing the postural function in healthy and pathological subjects. BioMed Res. Int. 891390 (2015).

Caballero, C., Barbado, D. & Moreno, F. J. What COP and kinematic parameters better characterize postural control in standing balance tasks? J. Mot. Behav. 47, 550–562 (2015).

Plisky, P. J. et al. The reliability of an instrumented device for measuring components of the star excursion balance test. N. Am. J. Sports Phys. Ther. NAJSPT. 4, 92–99 (2009).

Robinson, R. H. & Gribble, P. A. Support for a reduction in the number of trials needed for the star excursion balance test. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 89, 364–370 (2008a).

Plisky, P. J., Rauh, M. J., Kaminski, T. W. & Underwood, F. B. Star excursion balance test as a predictor of lower extremity injury in high school basketball players. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 36, 911–919 (2006).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Routledge, 1988). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Richardson, J. T. E. Eta squared and partial Eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educ. Res. Rev. 6, 135–147 (2011).

Hibbs, A. E., Thompson, K. G., French, D., Wrigley, A. & Spears, I. Optimizing performance by improving core stability and core strength. Sports Med. 38, 995–1008 (2008).

McGill, S. M. Low back stability: From formal description to issues for performance and rehabilitation. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 29, 26–31 (2001).

Ojeda, Á. C. H., Sandoval, D. A. C. & Barahona-Fuentes, G. D. Proprioceptive training methods as a tool for the prevention of injuries in football players: A systematic review. Arch. Med. Deporte. 36, 173–180 (2019).

Yılmaz, O., Soylu, Y., Erkmen, N., Kaplan, T. & Batalik, L. Effects of proprioceptive training on sports performance: A systematic review. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 16, 149 (2024).

Romero-Franco, N., Martínez-López, E., Lomas-Vega, R., Hita-Contreras, F. & Martínez-Amat, A. Effects of proprioceptive training program on core stability and center of gravity control in sprinters. J. Strength. Cond Res. 26, 2071–2077 (2012).

Park, J. Y., Bae, L. J. C., Cheon, M. W. & Jong-Jin & The effect of proprioceptive exercise on knee active articular position sense using biodex system 3pro®. Trans. Electr. Electron. Mater. 15, 170–173 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants for their voluntary participation, patience and availability. Besides, they would thank Dr. X for his contribution during data collection for this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each of the authors has read and concurs with the content in the final manuscript. F.C : Conceptualization, data analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft H.R, S.S: Resources K. A, A.R, N.P, S.B, S.S, H.R: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision W. B, A. H: Funding acquisition, Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee from the High Institute of Nursing, University of Sfax, Tunisia (CPP/SUD, approval number: 0206/2019).

Patient consent

Prior to enrollment, all participants gave their written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chaari, F., Alkhelaifi, K., Rahmani, A. et al. Acute effect of core stability exercises on static and dynamic postural balance in soccer players with groin pain. Sci Rep 15, 9086 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94368-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94368-5