Abstract

The use of machine learning algorithms and artificial intelligence in medicine has attracted significant interest due to its ability to aid in predicting medical outcomes. This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the random forest algorithm in predicting medical outcomes related to acute lithium toxicity. We analyzed cases recorded in the National Poison Data System (NPDS) between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2018. We highlighted instances of acute lithium toxicity in patients with ages ranging from 0 to 89 years. A random forest model was employed to predict serious medical outcomes, including those with a major effect, moderate effect, or death. Predictions were made using the pre-defined NPDS coding criteria. The model’s predictive performance was assessed by computing accuracy, recall (sensitivity), and F1-score. Of the 11,525 reported cases of lithium poisoning documented during the study, 2,760 cases were categorized as acute lithium overdose. One hundred thirty-nine individuals experienced severe outcomes, whereas 2,621 patients endured minor outcomes. The random forest model exhibited exceptional accuracy and F1-scores, achieving values of 99%, 98%, and 98% for the training, validation, and test datasets, respectively. The model achieved an accuracy rate of 100% and a sensitivity rate of 96% for important results. In addition, it achieved a 96% accuracy rate and a sensitivity rate of 100% for minor outcomes. The SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) study found factors, including drowsiness/lethargy, age, ataxia, abdominal pain, and electrolyte abnormalities, significantly influenced individual predictions. The random forest algorithm achieved a 98% accuracy rate in predicting medical outcomes for patients with acute lithium intoxication. The model demonstrated high sensitivity and precision in accurately predicting significant and minor outcomes. Further investigation is necessary to authenticate these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lithium has been a cornerstone in the treatment of bipolar disorder, providing significant mood stabilization benefits and reducing the risk of relapse1. However, its narrow therapeutic index of 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L and potential for toxicity warrant careful monitoring of serum lithium concentrations in patients undergoing treatment2. Acute lithium poisoning can occur via accidental ingestion or intentional ingestion in cases of attempted self-harm. While not always leading to toxicity, acute lithium exposure raises concerns for potential toxicity if the amount exceeds the individual’s therapeutic threshold. Toxicity generally occurs when concentrations exceed 1.5 mEq/L, with concentrations ≥ 4-5 mEq/L associated with severe clinical sequelae especially in patients with renal insufficiency3,4. However, some patients may experience symptoms of toxicity despite having serum concentrations within the therapeutic range. Acute lithium poisoning, whether unintentional or intentional, can lead to severe complications, primarily comprising adverse neurological manifestations5. Therefore, early recognition and appropriate management are crucial in mitigating adverse outcomes. The application of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) in medical settings has expanded rapidly in recent years6,7,8, with a growing interest in using these techniques to improve clinical decision-making, patient management, and outcome prediction9. Few studies have used ML on national poisoning data in medical toxicology10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17.

ML methods, like random forest and deep learning, can predict multiple toxicity endpoints such as acute oral toxicity and hepatotoxicity18. Integrating omics technology with ML improves the identification of biomarkers for early toxicity diagnosis19. ML algorithms have demonstrated considerable efficacy in forecasting the results of diverse poisoning exposures, utilizing data from the National Poison Data System (NPDS). Research has demonstrated the effectiveness of these models in predicting and identifying toxic agents, including organophosphates20, methanol16, and methadone21. Decision tree methods have been useful in managing extensive datasets. This has been exemplified by bupropion exposure effects22 and diphenhydramine exposure cases, both including large sample sizes, highlighting the exceptional efficacy of models such as Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM)23.

Additionally, ML has been employed to forecast seizures resulting from tramadol toxicity24, distinguish between repeated supra-therapeutic and acute acetaminophen exposures21,25, and ascertain risk factors for both purposeful and unintentional poisonings26. Developing a practical web application for antihyperglycemic agent poisoning27,28,29 and a triage system for mushroom poisoning30 underscores the efficacy of AI in public health. Ultimately, a model forecasting childhood lead poisoning demonstrated the efficacy of random forest algorithms31.

Random forest, a widely used ML algorithm, has demonstrated effectiveness in various medical applications, from disease diagnosis to predicting complications and treatment response32. However, the potential of random forest in predicting medical outcomes of acute lithium poisoning has not yet been extensively explored. The random forest algorithm has excelled in predicting poisonings in several scenarios, especially within clinical and toxicological environments. A study on diquat poisoning demonstrated that a random forest model attained a prediction accuracy of 0.95 ± 0.06 in assessing patient prognosis, highlighting the algorithm’s efficacy in clinical decision-making33. A pilot study used random forest and other ML algorithms to categorize poisoning exposures according to clinical symptoms. The model attained 77–80% accuracy in differentiating among distinct poisoning agents34.

Lithium toxicity can be exacerbated in individuals with renal insufficiency, as the kidney plays a crucial role in lithium elimination. Patients with pre-existing renal impairment prior to lithium therapy exhibit a markedly increased risk of developing severe chronic kidney disease, with a 10-year follow-up indicating a 48% incidence among individuals with elevated serum creatinine at the commencement of treatment35. Furthermore, prolonged lithium administration correlates with a dose-response relationship for chronic kidney disease, with risks escalating alongside duration and cumulative dosage36. Additionally, factors such as the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I). Angiotensin receptor blockers, and thiazides can further impact renal function and exacerbate lithium concentrations, increasing the risk of toxicity37,38.

This study aims to evaluate the performance of a random forest model in predicting medical outcomes related to acute lithium poisoning using NPDS data. By identifying the factors influencing the prediction of serious and minor outcomes, this study aims to assist clinicians in making informed decisions about patient management and contribute to helping mitigate acute lithium toxicity.

Methods

Data were obtained from the NPDS, which compiles case information from all regional poison centers in the United States. The NPDS is a valuable resource for investigating poisoning exposures and their medical outcomes39.

The Colorado Multidisciplinary Institutional Review Board (COMIRB#: 22-1088) granted a formal exemption for this study. De-identified NPDS data from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2018, involving single-agent lithium exposures for individuals of all age groups were examined.

In ML, a feature refers to an independent variable often used as input to predict a dependent variable. The NPDS dataset contained 133 features, with 131 being NPDS symptoms. All features, except for age, were binary variables. Age was a continuous variable. The algorithm’s dependent (target) variable was “medical outcome,” which had three categories in this study (major, moderate, and minor outcome). Moderate and minor outcomes were aggregated into a single group for model evaluation. The confusion matrix presented in the analysis is structured in a 2 × 2 format, concentrating solely on serious (major) and mixed outcomes.

To address missing data, we employed multiple imputation techniques, ensuring the robustness of our predictive model against incomplete records. Our investigation utilized the Markov Chain Monte Carlo methodology for multiple imputations. We selected this mostly due to its capability in managing intricate patterns of missing data and its allowance for integrating auxiliary variables that enhance the precision of our imputations.

We assumed missingness to be random and corroborated this assumption through sensitivity analyses, indicating that our results were stable across different imputation methods. This approach allowed us to maintain the integrity of our dataset while minimizing bias introduced by missing information.

This study tackled a supervised classification task where the target variable had three distinct categories. The initial phase of the ML process focused on data preparation, a crucial step in making the information suitable for model input. Our pre-processing efforts addressed two main challenges: handling missing data points and standardizing the variables.

Given that all features except age were binary, we paid specific attention to the age variable. To align it with the scale of the Boolean attributes, we applied normalization using the mean and standard deviation. Two methods were applied in order to standardize the age variable: min-max scaling (normalization) and standard scaling (z-score normalization):

This method brought the age to a comparable magnitude, which helped lower the model’s potential variance.

Initially, we investigated a deep learning strategy and established several parameters, such as the number of hidden layers, their size, and the learning rate. However, when the performance results were evaluated, we discovered that the random forest algorithm performed far better than the deep learning model. In light of this, we concentrated our efforts on the random forest model for our investigation.

After pre-processing, we partitioned the dataset randomly into three distinct subsets:

-

1.

Training data (70%).

-

2.

Validation data (15%).

-

3.

Testing data (15%).

Our approach involved training multiple models using the training dataset, each with different hyperparameter configurations. We then evaluated these models’ performance using the validation set, which allowed us to identify the most effective hyperparameter combination.

The final step involved selecting the best performing model based on its validation results. We then assessed the chosen model’s performance on the previously unseen testing dataset, providing an unbiased measure of its effectiveness and generalization capabilities.

Feature selection using recursive feature elimination with cross-validation (RFECV)

Feature selection is a method employed to pinpoint the most pertinent features in a dataset. It can enhance the model’s performance by minimizing overfitting, eliminating redundancy, and streamlining the model. In this study, RFECV is one of the feature selection approaches used to determine the most significant features in the medical dataset. RFECV systematically eliminates features and identifies the optimal subset based on the model’s cross-validated performance. This technique helps uncover the features most essential for predictions, ultimately enhancing the model’s accuracy and effectiveness.

Managing data imbalance

The Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) is a popular oversampling method for addressing the class imbalance issue in ML datasets. Class imbalance can negatively impact the performance of classification algorithms, as the model may be biased towards the majority class, resulting in poor predictive performance for the minority class. By generating synthetic samples for the minority class, SMOTE helps balance the class distribution, ensuring that the classification model can effectively learn from both the majority and minority classes. This study employed SMOTE prior to the application of the random forest algorithm. This pre-processing stage entailed choosing one or more k-nearest neighbors for each minority class instance and generating new synthetic examples, thus equilibrating the class distribution. Our objective was to augment the random forest model’s capacity to identify underlying patterns in the data and enhance its forecast accuracy, especially for the minority class. The application of SMOTE significantly enhanced the robustness and reliability of the classification model for predicting medical outcomes.

Machine learning approach

This work utilized the random forest method as the principal modeling technique owing to its durability and efficacy in managing complicated information, especially in medical toxicology.

Random forest is an ensemble learning technique that involves creating multiple decision trees during training and combining their outputs to produce the final prediction. The main objective of this approach is to enhance the model’s overall performance by mitigating overfitting and boosting stability, which are typical challenges encountered with individual decision trees. We meticulously selected the random forest algorithm for its ability to handle non-linear relationships and interaction effects among variables, with hyperparameters fine-tuned based on cross-validation to optimize prediction accuracy while minimizing the risk of overfitting. Its efficacy in handling noisy data and outliers renders it especially appropriate for our dataset, which displays uneven output characteristics. Due to the essential importance of a medical diagnosis, where precision is vital, random forest enables us to concentrate on challenging instances and enhance predictive performance.

The Scikit-learn library, a popular ML library in Python, provides an efficient and easy-to-use implementation of the random forest algorithm. In addition, scikit-learn offers various tools for data pre-processing, model training, evaluation, and fine-tuning, making it an ideal choice for researchers and practitioners working with ML models, including random forest. In random forest classification, five key hyperparameters play a critical role:

-

1.

Tree quantity (often labeled as n_estimators).

-

2.

Maximum tree depth (max_depth).

-

3.

Minimum sample threshold for node splitting (min_samples_split).

-

4.

Minimum sample requirement for leaf nodes (min_samples_leaf).

-

5.

Feature count considered at each split (max_features).

These parameters significantly influence the model’s behavior and effectiveness. Fine-tuning is crucial as they can greatly affect the following:

-

Overall performance.

-

Prediction accuracy.

-

Model’s ability to generalize.

Therefore, optimizing these hyperparameters is a vital step in the model development process, particularly during the training and validation phases. This optimization helps ensure the random forest classifier is well-suited to the specific characteristics of the dataset and the classification task at hand.

Evaluation of the model

Our analysis used confusion matrices for the training, validation, and testing datasets to evaluate the random forest model’s performance. These matrices offer a comprehensive overview of the model’s predictions, including correct classifications, errors, and the distribution of predictions across different medical outcomes.

The confusion matrix provides valuable insights by highlighting the following:

-

Accurate predictions.

-

Misclassifications.

-

Total instances per medical outcome.

-

Correctly identified cases.

-

False detections.

-

Distribution of predictions across outcomes.

The matrix presents true positives, false positives, and false negatives for each medical outcome. A positive result in this context signifies correctly identifying a specific medical outcome.

To thoroughly assess the random forest model’s effectiveness, we employed various performance metrics:

-

(1)

Overall accuracy: The percentage of correct predictions across all classes, offering a general measure of the model’s classification ability.

-

(2)

Specificity: The model’s capacity to identify true negatives demonstrates its ability to distinguish the majority class from others.

-

(3)

Precision: The proportion of correct positive predictions out of all positive predictions, indicating the model’s accuracy in classifying a specific class.

-

(4)

Recall (sensitivity): The percentage of true positives among all actual positives, showing the model’s ability to identify cases within a particular class.

-

(5)

F1-score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced measure of the model’s performance.

Additionally, we used graphical evaluation methods:

-

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve: This plots the true positive rate against the false positive rate across various thresholds, visually representing the model’s discrimination capability.

-

Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC-ROC): A single metric summarizing the ROC curve, with higher values indicating better performance.

Precision-Recall curve: This curve plots precision against recall at different thresholds to focus on the model’s performance for minority classes.

These diverse metrics and visualization techniques comprehensively understand the random forest model’s strengths and weaknesses, allowing for targeted improvements and ensuring reliable predictions. In imbalanced datasets, the Precision-Recall curve can be more informative than the ROC curve, as it highlights the trade-off between precision and recall, which are both crucial for the effective classification of the minority class. These curves offer a comprehensive view of the model’s performance across different thresholds and help identify the optimal trade-off between various performance metrics. This ultimately guides the fine-tuning of the random forest classifier for improved prediction of medical outcomes.

Explainability of the model with the Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) values

SHAP analysis is another valuable tool used in this study to interpret the predictions made by the random forest model. SHAP values are a unified measure of feature importance derived from cooperative game theory that assigns a contribution value to each feature in the model. These values help understand each feature’s impact on the prediction for individual instances and the entire model. The importance of SHAP analysis lies in its ability to provide interpretable insights into the model’s decision-making process, enabling researchers to identify the most influential features and understand how they contribute to the predictions.

Two plots can be created to visualize the SHAP values: summary and dependence plots. Summary plots display the global feature’s importance by ranking the features based on their average absolute SHAP values. In these plots, each dot represents a SHAP value for a feature and an instance, with the color indicating the feature’s value (e.g., high or low). The plot illustrates each feature’s positive or negative contribution to the model’s output.

Dependence plots demonstrate the relationship between a specific feature’s value and its corresponding SHAP value, revealing potential interactions between features and how they impact the predictions. By interpreting these figures, researchers can gain valuable insights into the model’s behavior, ultimately guiding model refinement and improving its overall performance in predicting medical outcomes.

Results

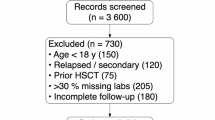

The research examined 11,525 lithium exposure cases, including 2,670 acute overdoses. One hundred thirty-nine patients experienced serious outcomes, while 2,621 had minor outcomes. The biological sex distribution was 1,763 females (three pregnant) and 995 males.

In order to improve the dependability of our findings, we carried out a comparative analysis using the random forest algorithm in conjunction with several different ML models. These models included Extreme Gradient Boosting, Extra Trees Classifier, Decision Tree, Light Gradient Boosting Machine, CatBoost Classifier, Gradient Boosting Classifier, Ada Boost Classifier, Linear Discriminant Analysis, K-Neighbors Classifier, and Support Vector Machine with a Linear Kernel (Table 1). In predicting outcomes associated with acute lithium poisoning, the performances of all models were evaluated based on important criteria such as accuracy, area under the curve (AUC), recall, and F1-score values. Based on the findings, it can be concluded that although the random forest algorithm produced results comparable to those of other models, other models exhibited unique benefits for the various outcomes. The results of this study provide a complete examination of the capabilities of several algorithms to make predictions, and they support our decision to use random forest in this investigation.

The random forest model’s performance in predicting outcomes was as follows (Tables 2, 3, and 4):

-

Training group: 99% accuracy and F1-score.

-

Validation group: 97% accuracy and F1-score.

-

Testing group: 98% accuracy and F1-score.

For the test set specifically:

-

Serious outcomes: 100% precision, 96% sensitivity.

-

Minor outcomes: 96% precision, 100% sensitivity.

Confusion matrices (Tables 4, 5, 6, and 7) illustrated all groups’ false detections and outcome distributions. For instance, in the test group (Table 7), 14 cases of serious outcomes were incorrectly classified as minor, while 389 serious outcome cases were correctly identified.

SHAP analysis revealed key factors influencing predictions (Fig. 1):

-

Drowsiness/lethargy.

-

Age.

-

Ataxia.

-

Abdominal pain.

-

Electrolyte abnormalities.

The model’s performance was further evaluated using ROC and Precision-Recall curves (Figs. 2 and 3):

-

AUC-ROC: 0.99 for both serious and minor outcomes.

-

Precision-Recall curve: Average precision of 1.00.

These results indicate that the random forest model is highly accurate in predicting the outcomes of acute lithium poisoning, with excellent performance across various metrics.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to assess the effectiveness of a random forest model in predicting the outcomes of acute lithium poisoning cases using NPDS. Our model exhibited a high accuracy of 98% in forecasting both serious and minor outcomes associated with acute lithium poisoning, demonstrating strong sensitivity and precision. The utilization of AI and ML in healthcare, particularly predictive modeling for acute medical situations such as poisoning, presents considerable potential for enhancing patient outcomes21,22,23,25,27,28,29,34,40,41. Our findings corroborate prior research, highlighting the need for early detection and proper treatment of lithium toxicity42,43,44. The primary predictors found in our model, including drowsiness/lethargy, age, ataxia, abdominal pain, electrolyte imbalances, acidosis, and bradycardia, can enhance patient management decision-making and innovative treatment techniques.

Bradycardia is a key predictor of lithium toxicity45. Older patients are more susceptible to lithium toxicity due to reduced renal clearance, requiring careful dose adjustment and monitoring46.

The characteristics of lithium poisoning typically encompass drowsiness, slurred speech, psychomotor retardation, polyneuropathy, memory impairment, and, in extreme instances, seizures, coma, and death47. Munshi et al. (2005) reported that lithium intoxication induces encephalopathy characterized by impaired mental status, cerebellar dysfunction, seizures, and stiffness48. Netto and Phutane (2012) asserted that delirium was the most prevalent sign of lithium poisoning3.

Lithium has a distinctive pharmacokinetic characteristic, absorbed from the upper gastrointestinal tract within roughly 8 h, with peak serum concentrations occurring 1–2 h post-ingestion49. Drowsiness and somnolence indicate early central nervous system toxicity, reflecting lithium’s disruption of neurotransmission, particularly serotonin and glutamate pathways50. Ataxia results from lithium’s impact on cerebellar function, often signaling progressive neurotoxicity in acute and chronic poisoning51.

Lithium distribution within the brain can be delayed by approximately relative to that in the plasma47,52. Consequently, patients with acute lithium poisoning may exhibit significantly elevated serum concentrations without obvious symptoms, but those with chronic intoxication may have sufficient time for extensive lithium distribution in the brain. Consequently, neurological toxicity may occur with moderately high serum lithium concentrations or even within typical therapeutic ranges53.

Abdominal pain is frequently observed due to lithium’s direct gastrointestinal irritation, often preceding systemic toxicity54. Lithium disrupts gastric mucosal function, causing nausea, abdominal pain, and vomiting, with dehydration and sodium imbalance worsening these effects, especially in those with kidney dysfunction55.

Lithium disrupts sodium and potassium homeostasis, affecting multiple organs56. Electrolyte imbalances, particularly sodium and potassium disturbances, contribute to cardiac instability and neuromuscular dysfunction, making them key indicators of severe poisoning57.

In a study by Vodovar D et al. (2016), the researchers explored predictive factors for the severity of lithium poisoning and the criteria for extracorporeal toxin removal (ECTR) to enhance patient outcomes. The authors discovered that a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of ≤ 10 and a lithium concentration of ≥ 5.2 mmol/L were significant predictors of poisoning severity upon admission. Additionally, their findings indicate that ECTR may be necessary if the serum lithium concentration is ≥ 5.2 mmol/L or creatinine is ≥ 200 µmol/L58. It is noteworthy that only 10% of the cases were categorized as acute lithium poisoning, while the remainder were acute-on-chronic or chronic lithium poisoning58. This distinction is significant as our study focuses exclusively on acute lithium poisoning, and the applicability of Vodovar et al.'s findings to our research may be limited. An investigation by Lee YC et al. (2011) assessed the outcomes of patients with any form of lithium poisoning. The authors found that patients with severe lithium poisoning had a higher prevalence of severe neurological symptoms, cardiovascular symptoms, and renal impairment than those with mild-to-moderate poisoning59. All patients recovered without chronic sequelae, demonstrating favorable outcomes59. While their study focused on Asian patients and used a smaller sample size, our study utilized a comprehensive dataset from the NPDS. It employed a random forest model to predict outcomes. Additionally, Lee et al. found that most poisonings were acute-on-chronic (47.6%) or chronic (33.3%), with acute poisoning being less common (19.0%)59. This distribution contrasts with our study’s focus on acute lithium poisoning.

A cross-sectional study conducted on 108 patients with lithium intoxication from 2001 to 2010 indicated that the recovery rate was substantially associated with BUN, creatinine, intubation, pCO2, pH, and HCO3−concentrations. Furthermore, a strong correlation was identified between the GCS and the recovery rate60. In a separate investigation, patients exhibiting lithium intoxication who presented to the Poison Control Center at Ain Shams University Hospitals from January 2011 to January 2015 underwent a prospective evaluation. All patients had previously been maintained on lithium therapy, and no acute cases were observed during the study period. The predominant clinical presentation observed in patients experiencing lithium intoxication was coma, which exhibited variable degrees of severity. The GCS was markedly diminished in non-survivors. Another predictive factor associated with severe outcomes was the presence of drug interactions, specifically involving diuretics or ACE-Is. However, no statistically significant age difference existed between survivors and non-survivors47.

We identified age as a significant prognostic determinant in the outcomes of patients affected by lithium toxicity. This observation can be ascribed to age-related alterations in pharmacokinetics, comorbid conditions, and administering concomitant medications in elderly patients. The pharmacokinetics of lithium may exhibit variations in the elderly population, attributable to a diminished volume of distribution and a decreased renal clearance. As individuals advance in age, the brain undergoes neurodegenerative, neurochemical, and neurophysiological alterations that may heighten sensitivity to lithium, potentially resulting in neurotoxicity at lower dosages47.

In addressing the potential for overfitting, we implemented several strategies to ensure our model’s robustness and generalizability. These included using cross-validation techniques during model training, optimizing the complexity of decision trees, and employing a separate validation dataset to evaluate the model’s performance. Such measures are crucial for developing a predictive model that remains accurate and reliable when applied to real-world clinical scenarios. Future research should explore methods for reducing overfitting and enhancing ML models’ predictive power and clinical utility in healthcare.

While our study demonstrates the potential of ML in predicting outcomes of acute lithium poisoning with high accuracy, it also underscores the necessity of addressing ethical considerations. These considerations include the mitigation of algorithmic biases and ensuring the equitable application of AI across diverse populations to uphold the principles of fairness and justice in healthcare decision-making. Integrating AI into clinical settings demands rigorous validation and a thoughtful examination of the effect on patient care across different demographics. As such, ongoing oversight and evaluation is necessary to identify and correct any unintended biases or disparities in care delivery. Ensuring transparency in developing and validating AI models and incorporating diverse datasets during their training is crucial for mitigating such risks. Furthermore, cultivating a multidisciplinary discourse among technologists, clinicians, ethicists, and patients is essential for addressing the ethical implications associated with AI in healthcare to ensure equitable and responsible application.

The limitations of this study warrant consideration. The present study utilized a retrospective design, which may have introduced bias and limited the ability to control for confounding factors. Future prospective studies are warranted to assess and validate random forest’s performance in distinguishing the outcomes of acute lithium poisoning. Other limitations include the possibility of incomplete or inaccurate documentation during the poison center call, which could stem from insufficient information provided to the specialist or transcription errors. In addition, diagnostic test results were not used, which may help to distinguish poisonings when clinical features are limited. Lastly, while this study conducted a cross-validation utilizing the NPDS dataset, it did not incorporate any external datasets for validation. This limitation may diminish the generalizability of the findings, as results may vary across various populations or clinical contexts. Validation studies, however, are necessary to confirm our findings across different populations and settings. While our model identified key predictors such as bradycardia, age, drowsiness, ataxia, abdominal pain, and electrolyte imbalances, future research should validate their predictive strength across diverse patient populations. Differences in renal function, comorbidities, and lithium pharmacokinetics may influence the generalizability of these findings in various clinical settings. This limitation reinforces the need for further external validation while acknowledging the potential variability in how these predictors manifest across different patient groups.

Future research should explore additional ML applications in this field, potentially uncovering new insights or enhancing predictive capabilities. How these predictive models can be integrated into clinical practice could amplify their real-world impact.

Conclusion

Our research demonstrates that a random forest ML model can accurately forecast outcomes in acute lithium toxicity incidents, highlighting its potential as a valuable tool in clinical settings. The model exhibited strong predictive capabilities for acute lithium poisoning outcomes and identified several crucial predictors.

These findings have significant implications. For clinicians, the identified predictors can assist in making more informed decisions about patient care, potentially improving patient outcomes. Our findings may contribute to developing new approaches for managing and reducing the severity of acute lithium toxicity.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Malhi, G. S. & Outhred, T. Therapeutic mechanisms of lithium in bipolar disorder: recent advances and current Understanding. CNS Drugs 30, 931–949 (2016).

Timmer, R. T. & Sands, J. M. Lithium intoxication. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10, 666–674 (1999).

Netto, I. & Phutane, V. H. Reversible lithium neurotoxicity: review of the literature. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disorders 14, 27249 (2012).

Schneider, M. A. & Smith, S. S. Lithium-Induced neurotoxicity: a case study. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 51, 283–286 (2019).

Yatham, L. N. et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) and international society for bipolar disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 20, 97–170 (2018).

Rush, B., Celi, L. A. & Stone, D. J. Applying machine learning to continuously monitored physiological data. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 33, 887–893 (2019).

Chang, Y. S. et al. Predicting cochlear dead regions in patients with hearing loss through a machine learning-based approach: A preliminary study. PloS One 14, e0217790 (2019).

Patterson, B. W. et al. Training and interpreting machine learning algorithms to evaluate fall risk after emergency department visits. Med. Care 57, 560 (2019).

Jiang, F. et al. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: past, present and future. Stroke Vascular Neurol. 2 (2017).

Chary, M., Burnsa, M. & Boyerb, E. Tak: the computational toxicological machine. 39th international Congress of the European association of poisons centres and clinical toxicologists (EAPCCT) 21–24 May 2019, Naples, Italy. Clin. Tox. 57, 482 (2019).

Chary, M., Boyer, E. W. & Burns, M. M. Diagnosis of acute poisoning using explainable artificial intelligence. Comput. Biol. Med. 104469 (2021).

Nogee, D., Haimovich, A., Hart, K. & Tomassoni, A. Multiclass classification machine learning identification of common poisonings. North American Congress of clinical toxicology (NACCT) abstracts 2020. Clin. Toxicol. 58, 1083–1084 (2020).

Nogee, D. & Tomassoni, A. Development of a prototype software tool to assist with toxidrome recognition. North American Congress of clinical toxicology (NACCT) abstracts 2018. Clin. Toxicol. 56, 1049–1049 (2018).

Chary, M. A., Manini, A. F., Boyer, E. W. & Burns, M. The role and promise of artificial intelligence in medical toxicology. J. Med. Toxicol., 1–7 (2020).

Mohtarami, S. A. et al. Prediction of Naloxone dose in opioids toxicity based on machine learning techniques (artificial intelligence). DARU J. Pharm. Sci., 1–19 (2024).

Rahimi, M. et al. Prediction of acute methanol poisoning prognosis using machine learning techniques. Toxicology 504, 153770 (2024).

Mostafazadeh, B. et al. Prediction of pralidoxime dose in patients with organophosphate poisoning using machine learning techniques. Health Scope 13 (2024).

Cavasotto, C. N. & Scardino, V. Machine learning toxicity prediction: latest advances by toxicity end point. ACS Omega 7, 47536–47546 (2022).

Son, A. et al. Utilizing Omics Technologies and Machine Learning to Improve Predictive Toxicology. (2024).

Hosseini, S. M. et al. Prediction of acute organophosphate poisoning severity using machine learning techniques. Toxicology 486, 153431 (2023).

Mehrpour, O., Saeedi, F., Vohra, V. & Hoyte, C. Outcome prediction of methadone poisoning in the United States: implications of machine learning in the National Poison Data System (NPDS). Drug and chemical toxicology, 1–8 (2023).

Mehrpour, O., Saeedi, F., Abdollahi, J., Amirabadizadeh, A. & Goss, F. The value of machine learning for prognosis prediction of diphenhydramine exposure: National analysis of 50,000 patients in the united States. J. Res. Med. Sci. 28, 49 (2023).

Mehrpour, O. et al. The role of decision tree and machine learning models for outcome prediction of bupropion exposure: A nationwide analysis of more than 14 000 patients in the united States. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 133, 98–110 (2023).

Behnoush, B. et al. Machine learning algorithms to predict seizure due to acute Tramadol poisoning. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 40, 1225–1233 (2021).

Mehrpour, O., Saeedi, F. & Hoyte, C. Decision tree outcome prediction of acute acetaminophen exposure in the united States: a study of 30,000 cases from the National poison data system. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 130, 191–199 (2022).

Veisani, Y. et al. Comparison of machine learning algorithms to predict intentional and unintentional poisoning risk factors. Heliyon 9 (2023).

Mehrpour, O., Hoyte, C., Nakhaee, S., Megarbane, B. & Goss, F. Using a decision tree algorithm to distinguish between repeated supra-therapeutic and acute acetaminophen exposures. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 23, 102 (2023).

Mehrpour, O. et al. Comparison of decision tree with common machine learning models for prediction of Biguanide and sulfonylurea poisoning in the united States: an analysis of the National poison data system. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 23, 60 (2023).

Mehrpour, O., Saeedi, F., Hoyte, C., Goss, F. & Shirazi, F. M. Utility of support vector machine and decision tree to identify the prognosis of Metformin poisoning in the united States: analysis of National poisoning data system. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 23, 49 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Early triage of critically ill adult patients with mushroom poisoning: machine learning approach. JMIR Formative Res. 7, e44666 (2023).

Potash, E. et al. Validation of a machine learning model to predict childhood lead poisoning. JAMA Netw. Open. 3, e2012734–e2012734 (2020).

Liaw, A. & Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomforest. R News 2, 18–22 (2002).

Hu, H. et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of Diquat plasma concentration and complete blood count in patients with acute Diquat poisoning based on random forest algorithms. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 43, 09603271241276981 (2024).

Mehrpour, O. et al. Classification of acute poisoning exposures with machine learning models derived from the National poison data system. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 131, 566–574 (2022).

Golic, M. et al. Should impaired renal function be considered a contra-indication for starting lithium? Nord. J. Psychiatry 75, S7–S7 (2021).

Kawada, T. Lithium use and the risk of chronic kidney disease. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 132 (2023).

Finley, P. R. Drug interactions with lithium: an update. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 55, 925–941 (2016).

Tobita, S. et al. The importance of monitoring renal function and concomitant medication to avoid toxicity in patients taking lithium. Int. Clinic. Psychopharm. 36(1), 34–37 (2021).

Gummin, D. D. et al. 2019 Annual report of the American Association of poison control centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 37th annual report. Clinical Toxicology 58, 1360–1541 (2020).

Mehrpour, O. et al. Deep learning neural network derivation and testing to distinguish acute poisonings. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 19, 367–380 (2023).

Mehrpour, O. et al. Utility of artificial intelligence to identify antihyperglycemic agents poisoning in the USA: introducing a practical web application using National poison data system (NPDS). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 57801–57810 (2023).

Murphy, N., Redahan, L. & Lally, J. Management of lithium intoxication. BJPsych Adv. 29, 82–91 (2023).

Netto, I., Phutane, V. H. & Ravindran, B. Lithium neurotoxicity due to second-generation antipsychotics combined with lithium: A systematic review. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disorders 21, 27431 (2019).

Suwanwongse, K. & Shabarek, N. Lithium toxicity in two coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients. Cureus 12 (2020).

Nakamura, M., Nakatsu, K. & Nagamine, T. Sinus node dysfunction after acute lithium treatment at therapeutic levels. Innovations Clin. Neurosci. 12, 18 (2015).

Rej, S. et al. Association of lithium use and a higher serum concentration of lithium with the risk of declining renal function in older adults: a population-based cohort study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 81, 10411 (2020).

Khater, A. & Sarhan, N. Evaluation of neurotoxicity in lithium treated patients admitted to poison control Center-Ain Shams university hospitals during the years (2011–2014). Ain Shams J. Forensic Med. Clin. Toxicol. 25, 1–9 (2015).

Munshi, K. R. & Thampy, A. The syndrome of irreversible lithium-effectuated neurotoxicity. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 28, 38–49 (2005).

Malhi, G. S., Tanious, M., Das, P. & Berk, M. The science and practice of lithium therapy. Australian & New Zealand J. Psychiatry 46(3), 192–211 (2012).

Hashimoto, R., Hough, C., Nakazawa, T., Yamamoto, T. & Chuang, D. M. Lithium protection against glutamate excitotoxicity in rat cerebral cortical neurons: involvement of NMDA receptor Inhibition possibly by decreasing NR2B tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Neurochem. 80, 589–597 (2002).

Yamantürk-Çelik, P., Ünlüçerçi, Y., Sevgi, S., Bekpinar, S. & Eroğlu, L. Nitrergic, glutamatergic and Gabaergic systems in lithium toxicity. J. Toxicol. Sci. 37, 1017–1023 (2012).

Finley, P. R., Warner, M. D. & Peabody, C. A. Clinical relevance of drug interactions with lithium. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 29, 172–191 (1995).

Colvard, M. D., Gentry, J. D. & Mullis, D. M. Neurotoxicity with combined use of lithium and haloperidol decanoate. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disorders 15, 27036 (2013).

Paudel, U. et al. Lithium toxicity: a case report. J. Patan Acad. Health Sci. 10, 68–71 (2023).

Grandjean, E. M., Aubry, J. M. & Lithium Updated human knowledge using an evidence-based approach. CNS Drugs 23, 225–240 (2009).

Ahmed, I. et al. Laser induced breakdown spectroscopy with machine learning reveals lithium-induced electrolyte imbalance in the kidneys. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 194, 113805 (2021).

Singh, D., Akingbola, A., Ross-Ascuitto, N. & Ascuitto, R. Electrocardiac effects associated with lithium toxicity in children: an illustrative case and review of the pathophysiology. Cardiol. Young 26, 221–229 (2016).

Vodovar, D., El Balkhi, S., Curis, E., Deye, N. & Mégarbane, B. Lithium poisoning in the intensive care unit: predictive factors of severity and indications for extracorporeal toxin removal to improve outcome. Clin. Toxicol. 54, 615–623 (2016).

Lee, Y. C. et al. Outcome of patients with lithium poisoning at a far-east poison center. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 30, 528–534 (2011).

Mostafazadeh, B., Ghotb, S., Najari, F. & Farzaneh, E. Acute lithium intoxication and factors contributing to its morbidity: a 10-year review. Int. J. Med. Toxicol. Forensic Med. 6, 1–6 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OM, SN, VV, SAM, and FS contributed to the manuscript’s conception, design, and preparation. OM conducted data collection and was involved in data acquisition and interpretation. SN, VV, SAM, and OM played significant roles in drafting the manuscript and critically revising it for intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclaimers

The NPDS, maintained by America’s Poison Centers (APC), collects information from Poison Centers (PCs) across the nation. These records include self-reported cases and records of exposure management. However, it is important to acknowledge that NPDS data may not capture all instances of exposure to specific substances, as some cases might not be reported to PCs, potentially leading to an underestimation of total exposures. Furthermore, NPDS data should not be viewed as definitive evidence of poisoning or overdose incidents since the system relies on reported information that may only sometimes be independently verified. While the APC maintains the NPDS, it does not fully authenticate each report, meaning there may be variations in the accuracy of specific case details. Consequently, any conclusions or insights drawn from NPDS data should be interpreted with caution, as these findings may not necessarily align with or represent the official stance of the APC. These considerations highlight the need to carefully interpret NPDS data and underscore the importance of being aware of potential limitations when using this information for research or policy decisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Our research methods adhered to all applicable guidelines and regulations. The data used in this study was obtained from the NPDS in a de-identified format. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board on Human Subjects Protection has established guidelines for determining whether a study qualifies as human subjects research. According to these guidelines, our analysis of NPDS data does not meet the criteria outlined in 45 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 46.101(b) for human subjects research. Consequently, formal IRB approval was optional for this study. It is important to note that certain research categories, classified as exempt research, are not subject to federal regulations and can proceed without formal IRB review and approval. To qualify for this exemption, research activities must involve minimal risk and meet specific criteria defined in federal regulations 45 CFR 46.101(b). In our case, the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board on Human Subjects Protection reviewed our study protocol and determined that it met the criteria for exemption. This decision is documented under COMIRB#22-1088. This exemption status indicates that while our research involves human data, it poses minimal risk and falls within the parameters that allow for streamlined ethical review processes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mehrpour, O., Vohra, V., Nakhaee, S. et al. Machine learning for predicting medical outcomes associated with acute lithium poisoning. Sci Rep 15, 14468 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94395-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94395-2