Abstract

The increasing resistance of bacteria to antimicrobials is a major threat to public health. This study investigates the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance, both phenotypic and genotypic, among Campylobacter isolates from Australian meat chickens in 2022, as a follow up to investigate trends since the last national surveillance undertaken in 2016. Isolates (n = 186) were obtained at slaughter from 200 pooled cecal samples taken from 1,000 meat chickens. The majority of C. jejuni (68.7%) and C. coli (88.9%) isolates were susceptible to all the antibiotics that were tested, and no multi-drug resistance was found. Resistance to ciprofloxacin (fluoroquinolone) was detected in 24.4% of the C. jejuni and 3.2% of the C. coli isolates. Whole genome sequencing revealed a diverse range of sequence types (STs). These included 32 previously reported STs for C. jejuni and 13 for C. coli, as well as four and seven previously undescribed STs for each species, respectively. The STs containing fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates were ST2083, ST10130, ST2895, ST7323, ST2398, and ST1078 for C. jejuni, and ST860 and ST894 for C. coli. Although fluoroquinolones are not used in animal production in Australia, resistance amongst C. jejuni isolates was high (24.4%). This finding emphasizes the need for enhanced surveillance and regular sampling along the food chain to understand the source of the isolates and to mitigate risks of antimicrobial resistance to protect public health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Species of the bacterial genus Campylobacter are commonly found in the gut of warm-blooded animals, with some being important foodborne zoonotic pathogens worldwide1,2. Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli are the predominant species that cause gastrointestinal infections in humans3. Infections are most frequently attributed to the consumption of undercooked/raw chicken4, but other factors such as direct contact with live birds, consumption of cross-contaminated food, as well as drinking untreated milk and water also present risks for infection4,5. In affected individuals, symptoms include acute watery or bloody diarrhea, fever, weight loss, and cramps, while on rare occasions infections can result in neurological sequelae such as Guillain-Barre syndrome5. Campylobacteriosis is notifiable in countries such as Australia, where reports from the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System highlight a notification rate of 143.5 cases per 100,000 in 2019 4. They further stated that the Australian notification rate is increasing as compared to some other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries such as the United Kingdom (96.8 cases in 2017), the USA (19.5 cases in 2018) and the European Union (59.7 cases in 2019)6.

Campylobacteriosis is usually self-limiting and antimicrobial treatment is often only required in severe cases or in patients with a compromised immune status. In such instances, fluoroquinolones (e.g. ciprofloxacin) and macrolides (e.g. erythromycin) are recommended for treatment7. Globally, the rates of resistance to highly important antimicrobials (e.g. tetracyclines), critically important antimicrobials (e.g. macrolides) and highest priority critically important antimicrobials (e.g. fluoroquinolones) have been increasing, and that constitutes a major public health concern8,9,10,11. For this reason, the World Health Organization, the World Organization for Animal Health and other international agencies have recommended the monitoring and surveillance of emerging antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in order to understand possible areas of risk for the development of resistance as well as acting as a guide for interventions and risk management strategies12,13,14. Globally, the emergence of resistance to critically important antimicrobials in zoonotic pathogens in livestock is thought to be directly attributed to selection pressures arising from their use in livestock production systems15.

Unexpectedly, an Australian national survey of AMR in Campylobacter isolates from Australian meat chickens conducted in 2016 identified the emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance among C. jejuni (14.8%) and C. coli (5.4%) in the absence of direct fluoroquinolone use16. The predominant sequence types (STs) containing fluoroquinolone-resistant (FQ-R) isolates were ST2083, ST2343, and ST7323 for C. jejuni and ST860 for C. coli, which indicate a putative population overlap with those found in humans and animals in other international studies. Consequently, due to the absence of fluoroquinolone use in poultry production, it was hypothesized that FQ-R Campylobacter spp. likely have been introduced into Australian poultry by contact with sources such as humans, pest species and wild animals. Since 2016, there has been no further investigation into fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter in the Australian poultry industry, leaving uncertainty about the persistence of these resistant strains16, and it is unclear if these organisms are still present in Australian meat chickens in the absence of direct selection pressure. Given the increasing global concerns regarding antimicrobial resistance and the lack of recent data on fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter in Australian meat chickens, a follow-up study was undertaken to assess whether these resistant strains have persisted or changed over time. Understanding the current prevalence and genetic characteristics of these isolates is critical for identifying potential sources of resistance and informing food safety policies. To address this knowledge gap, this study aimed to evaluate the current prevalence of antimicrobial resistance (phenotypic and genotypic) among Campylobacter isolates from Australian meat chickens. Additionally, we investigated the genetic diversity and relationships among the isolates, with a focus on FQ-R and fluoroquinolone-susceptible (FQ-S) isolates of C. jejuni and C. coli.

Results

Numbers of isolates and characterization of antimicrobial resistance

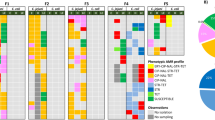

A total of 186 individual Campylobacter isolates (123 C. jejuni and 63 C. coli) were obtained from the 200 pooled cecal samples, of which 178 gave clear minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) results and so passed this quality control interpretation step. Of these 178 isolates, 115 were identified as C. jejuni and 63 as C. coli based on phenotypic characterization. Antimicrobial resistance patterns based on epidemiological cut-off values (termed resistant or susceptible) are shown in Fig. 1A and B. The MIC distribution is shown in Tables S1 and S2 (Supplemental Material). All isolates were susceptible to azithromycin, erythromycin, chloramphenicol, clindamycin, gentamicin, telithromycin, florfenicol, and gentamicin.

AMR in Campylobacter jejuni

Overall, 79 (68.7%) of the 115 C. jejuni isolates showed no phenotypic resistance to any of the antimicrobials tested, and none of the resistant isolates were classified as being multidrug resistant (MDR) (Table 1). The highest rates of resistance were to the fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin (24.4%), the quinolone nalidixic acid (21.7%), and to tetracycline (18.3%). Only four antimicrobial resistance profiles were detected, these being resistance to aminoglycosides; quinolones; tetracyclines; and quinolones and tetracyclines.

AMR in Campylobacter coli.

No phenotypic resistance was detected in 56 (88.9%) of the 63 C. coli isolates. Of the isolates where resistance was detected, this was to nalidixic acid (n = 3; 4.8%), ciprofloxacin (n = 2; 3.2%), streptomycin (n = 2; 3.2%), and tetracycline (n = 1; 1.6%) (Fig. 1B). These rates were all highly significantly lower than for C. jejuni (p < 0.01), with corrected Chi-square values of 7.6, 11.6 and 8.9 for the three antimicrobials, respectively. Three resistance profiles were identified (aminoglycosides, quinolones and tetracyclines), and as with C. jejuni, no MDR phenotype was detected (Table 1).

Comparison of resistance rates in 2016 and 2022

The C. jejuni resistance rates for ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid in the 2022 survey were higher than, but not significantly different from the rates in the 2016 survey (Fig. 2A). No significant differences in resistance rates were found between the C. coli isolates from the two surveys (Fig. 2B).

Comparison of resistance to selected antimicrobials in C. jejuni (2 A: Previous study (2016) n = 108, current study n = 115) and C. coli (2 B: Previous study (2016) n = 96, current study n = 63) isolated from Australian chicken ceca in 2016 and 2022. The percent resistance refers to breakpoints. Only antimicrobials used in both studies with breakpoints available were included. Error bars refer to 95% confidence intervals.

Genomic analysis of Campylobacter isolates.

Of the 186 Campylobacter isolates that were subjected to whole genomic sequencing, 177 generated sufficient reads for useful analysis. Of these, 117 were identified as C. jejuni and 60 as C. coli using Barrnap and Kraken. On average, the genome sizes and GC contents in this collection were 1.41 Mb and 30.9% for C. jejuni, and 1.95 Mb and 30.3% for C. coli.

Campylobacter jejuni AMR determinants

A total of 19 AMR determinants were identified from the pooled genomic data for the 117 sequenced C. jejuni isolates (Supplementary Fig. 1). These included a large collection of genes associated with beta-lactam resistance, including blaOXA, blaOXA−61, blaOXA−184, blaOXA−193, blaOXA−449, blaOXA−452, blaOXA−460, blaOXA−461, blaOXA−466, blaOXA−591, blaOXA−592, blaOXA−625, and blaOXA−785. Resistance determinants for other drug classes including macrolides (i.e., mutations in the 50 S rRNA gene), tetracyclines (i.e., presence of tet(O/M/O) and tet(O) genes), and fluoroquinolones (i.e., mutations in the DNA gyrase A subunit gene gyrA) were also detected. The genes acr3 and arsP, encoding efflux pump (resistance to roxarsone) and methylarsenite efflux permease, respectively16, were also identified. Isolates identified as FQ-R had a single mutation, T86I, in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) of the gyrA, which is known to decrease the sensitivity of Campylobacter spp. to quinolones. The C. jejuni AMR gene determinant data aligned with the antimicrobial susceptibility results for the drugs that were selected for testing in the study.

Campylobacter jejuni sequence types and AMR determinants.

The 117 sequenced C. jejuni isolates belonged to 32 known sequence types (STs), with the dominant ones being ST10143 (n = 16; 14%), ST48 (n = 12; 10%), ST2083 (n = 11; 9%), ST46 (n = 6; 5%) and ST583 (n = 6; 5%) (Table 2). The STs and the respective resistance gene patterns of the isolates are shown in Fig. 3. The most dominant ST (ST10143) accounted for 33% of isolates and these were neither resistant nor had beta-lactamase oxacillinase (blaOXA) resistance genes. Overall, 29 C. jejuni isolates showed an T86I mutation (24.8%) in the QRDR of the gyrA, which is known to decrease the sensitivity of Campylobacter spp. to quinolones. These isolates belonged to ST2083 (n = 11), ST10130 (n = 4), ST2895 (n = 4), ST7323 (n = 4), ST2398 (n = 4), and ST1078 (n = 2). Among the 11 isolates from the second most dominant ST, ST2083 (9.2%), ten carried a gyrA mutation linked to FQ-R. The STs with isolates showing dual resistance determinants (fluoroquinolone and tetracycline) were ST1078 (n = 2), ST2083 (n = 3), ST10130 (n = 3), ST2398 (n = 4), and ST2895 (n = 4). While isolates belonging to ST2083 previously were detected in the 2016 survey, as well as in human cases of gastroenteritis16, the other STs were only detected in the current 2022 survey collection.

Relatedness of the different sequence types (STs) of the Campylobacter jejuni strains based on shared alleles, presented as a midpoint rooted phylogenetic tree was constructed by IQTree option in Gubbins. Graphical visualization of the phylogenetic tree generated was performed via the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL). Red circles highlight clusters which harbour FQ-R strains.

Campylobacter jejuni phylogenetic relationships.

The relationship between the C. jejuni isolates was initially assessed using core genome phylogeny (Fig. 3). The different STs clustered individually but were widely dispersed across the phylogenetic tree, reflecting the high diversity of C. jejuni isolates in this study. Genomic analysis demonstrated that the FQ-R strains belonged to a small subgroup of strains (ST2083, ST2398, ST7323 and ST2895) (Fig. 3). Of these, only ST2895 was assigned to a previously described ST574 complex. The dominant ST recorded among the C. jejuni genomes was ST10143 (of the ST353 complex), but this did not contain any FQ-R strains.

The relatedness of the C. jejuni population was further investigated by core genome SNP analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2). The analysis showed clustering of 13 complexes, which encompassed 33 different STs. The distribution of various STs and their related complexes demonstrated the diversity of this collection. The FQ-R strains were mainly found in ST2083, ST7323 and ST2398, which are yet to be assigned with any complexes. Among the FQ-R strains residing within these STs, those of ST2083 and ST7323 appeared to be situated in different clades (Supplementary Fig. 2). Apart from these STs, other FQ-resistant strains were found clustering within known complexes such as the ST52, ST574 and ST443 complexes. The genomes of most of the C. jejuni isolates belonging to any given ST were conserved and clustered together, despite the overall diversity of the collection. There were no fixed patterns in the resistome at the cluster level.

Campylobacter coli AMR determinants.

Twelve AMR determinants were detected amongst the pooled genomic data for the 60 C. coli isolates that passed quality control (Supplementary Fig. 1). Compared to C. jejuni, the C. coli genomes had fewer genes responsible for beta-lactam resistance (only blaOXA, blaOXA−193, blaOXA−489, blaOXA578, and blaOXA−784 were recorded). Apart from mechanisms for macrolide resistance (50 S), tetracycline resistance (tet(O)) and fluoroquinolone resistance (gyrA), which were identified in both datasets, the genomes of C. coli also contained other resistance determinants (Supplementary Fig. 1). These included mutations in the 23 S rRNA gene that contributing to macrolide resistance, the aad9 gene responsible for aminoglycoside resistance, the lnu(C) gene responsible for lincosamide resistance, and the rpsL gene associated with streptomycin resistance. The C. coli AMR gene determinant data aligned with the antimicrobial susceptibility results for the drugs that were selected for testing in the current study.

Campylobacter coli STs and AMR determinants.

Thirteen STs were identified amongst the 60 sequenced C. coli isolates in this study, with the most predominant being ST827 (n = 17; 28%) and ST825 (n = 15; 25%). Other STs identified were ST9419 (n = 5), ST6775 (n = 4), ST1017 (n = 3), ST583 (n = 1), ST828 (n = 1), ST829 (n = 1), ST860 (n = 2), ST894 (n = 1), ST1181 (n = 1), ST1243 (n = 1), ST4175 (n = 1), and seven novel STs. A comparison of the number of STs identified for the C. jejuni and C. coli isolates is shown in Table 2. The most prevalent blaOXA genes associated with C. coli isolates were blaOXA−193 (n = 18), blaOXA−489 (n = 17) and blaOXA−784 (n = 5). While neither fluoroquinolone nor tetracycline resistance genes were associated with ST827, all the isolates in this ST carried an associated blaOXA−489. Only two of the 60 C. coli isolates (3.3%) were resistant to fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin), with both having the same T86I mutation in gyrA as found in the 29 FQ-R C. jejuni isolates. The FQ-R C. coli belonged to ST860 and ST894 (Supplementary Fig. 3), of which ST860 previously has been identified in chickens and humans from the United Kingdom and Germany16.

Campylobacter coli phylogenetic relationships.

As with C. jejuni, the relationship between the C. coli isolates was initially assessed using core genome phylogeny that indicated a diverse genetic background cluster based on STs (Fig. 4). Fluroquinolone resistant C. coli belonged to two distinct STs (ST860 and ST894) that are part of globally disseminated C. coli clonal complex (CC) CC828. Subsequent core SNP analysis confirmed diversity amongst the C. coli strains (Supplementary Fig. 3), and although most were CC ST828 (n = 42, 70%), there were no apparent clusters among the local strains.

A midpoint rooted phylogenetic tree of 60 Campylobacter coli isolates constructed using the IQTree option in Gubbins. Graphical visualization of the phylogenetic tree generated was performed via the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL). Each node on the end of a branch represents an individual C. coli sample in this study. Red color represents fluoroquinolone-resistant (FQ-R) strains.

Discussion

This study reports on the phenotypic AMR and genomic characteristics of Campylobacter spp. isolated in 2021–2022 from Australian meat chickens, and compares these to results obtained in a national survey undertaken in 2016. Low rates (< 5%) of single drug resistance towards ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid and tetracycline were observed in C. coli, while the rates for C. jejuni were significantly higher (24.4% to ciprofloxacin, 21.7% to nalidixic acid and 18.6% to tetracycline). Importantly, these rates were not significantly different from the previously reported rates for 2016 16. No multidrug resistance was found for either species. The Campylobacter isolates were diverse, as indicated by the presence of 32 STs for C. jejuni and 13 STs for C. coli, results similar to those in the previous Australian study, where 32 STs and 10 STs were recorded for C. jejuni and C. coli respectively16. This suggests the persistence of specific strains amongst Australian meat chickens between 2016 and 2022 in the absence of selective pressure from fluoroquinolone use.

The low levels of fluoroquinolone resistance (3.2%) among C. coli isolates in this study were similar to reports from other studies in Australia16,17,18 and Denmark19; however, a relatively high FQ-R rate (24.4%) was found for C. jejuni. In earlier studies in Australia, no ciprofloxacin resistance was found among isolates from intensively raised meat chickens or free-range egg layers18, while in isolates from retail chicken meat, resistance to fluoroquinolones was found in over 7.5% of C. coli and in 11.5% of C. jejuni isolates20. In contrast, higher rates have been reported in the EU where ciprofloxacin resistance was 61.5% and 61.2% for C. jejuni and C. coli, respectively21. These levels may be reflective of problems with the efficiencies of national policies on the use of fluoroquinolones. Quinolone resistance by Campylobacter in chickens in Australia remains relatively low, presumably due to the regulatory prohibition on the use of fluoroquinolones in food-producing animals, strict border regulations and the unique isolated geographical location4,22,23. Therefore, the observed fluoroquinolone resistance may have been introduced into chicken farms by sources such as wild animals or birds, pest species, human movement, and/or vehicles16,24. Additionally, feed could be a potential source of Campylobacter on farms as the bacteria can survive and multiply in foods under different storage temperatures; hence, enhanced biosecurity practices are the most appropriate ways to decrease infection at the flock level24.

Even though the resistance rates to fluoroquinolone amongst Australian C. jejuni isolates were higher in 2022 compared to 2016, this difference was not significant. The persistence of fluoroquinolone resistance was unexpected as fluoroquinolones are not permitted for use in animal production in Australia, and hence, a decline in resistance rates was anticipated, as seen with other antimicrobials such as tetracycline and erythromycin. The fact that this did not occur may reflect the key roles that the birds and their environment play in amplifying and disseminating the pathogen in commercial farms, thereby complicating control25. More specifically, fluoroquinolone-resistant C. jejuni with a specific gyrA point mutation (T86I) have been reported to be fitter than wild-type strains in their ability to colonize and persist in the chicken gut9,26. The key mechanism behind this situation might be the alteration of DNA supercoiling activity (after the T86I gyrA point mutation occurs), which further affects the fitness cost in C. jejuni27. However, in agreement with the results of the current study, this effect was not observed in C. coli in the in vitro part of a study by Zeitouni and Kempf, despite the presence of the same gyrA point mutation (T86I)27. The micromolecular mechanism(s) that may be associated with this variation between species (such as DNA supercoiling activity) should be further studied to obtain a more detailed explanation of these differences. Screening of antimicrobial genes from whole genome sequencing data detected the blaOXA genes in a large proportion of C. jejuni and C. coli. However, the clinical significance is limited, as beta-lactams particularly penicillin and narrow-spectrum cephalosporins are intrinsically resistant in due to the alterations in membrane structure, porin proteins, and the efflux pump system28,29. Consequently, beta-lactams are not included in routine phenotypic AMR testing, and no clinical breakpoints for human infections and animals exist. Antimicrobial resistant genomic screenings in Campylobacter spp. should be interpreted cautiously, as they may not reflect intrinsic resistances and could lead to misinterpretation in antimicrobial resistant curation.

In this study, the genetic diversity of Campylobacter was emphasized by the high number of different STs detected. Some STs, such as ST860, ST825 and ST2083, which contained FQ-R C. jejuni isolates, previously have been identified in humans, poultry and pigs in the United Kingdom, Germany and Japan30,31, and are frequently reported in cases of human campylobacteriosis32. ST10130 and ST10143 have only been identified in Australia. In the previous survey from 2016 16, FQ-R strains also were found in ST2083 and ST7323, suggesting that they have persisted at least since then. However, in the current study FQ-resistant strains also were found in ST2398, which was previously undetected. The emergence of ST2398 with FQ-R, distantly located from ST2083 and ST7323 (Supplementary Fig. 2), may indicate that these are a new group of C. jejuni with recently developed fluoroquinolone resistance. Fluoroquinolone resistance mostly arises from a mutation in the QRDR of the gyrA gene (T86I mutation)33,34, and this was detected in FQ-R isolates from both species in this study. These mutations are similar to those found in human clinical isolates where they confer high ciprofloxacin resistance35. Additionally, the tet(O) gene responsible for tetracycline resistance was detected in both C. jejuni and C. coli. This gene has previously been reported in C. jejuni and C. coli isolates from Australia16,20,36. Furthermore, the fact that most of the C. coli genomes in this study (n = 42, Fig. 4) were categorised to the same CC suggested that there may have been spread of international clones among the Australian chickens. Hence, the detection of FQ-R strains may be the result of imported resistance from human carriage and/or other wildlife introduced into the Australian ecosystem.

In summary, the current Australian national survey from 2022 showed that antimicrobial resistance rates in C. jejuni and C. coli from the ceca of meat chickens remain relatively low and have not significantly changed in the last six years. Importantly, rates of resistance to fluoroquinolones in C. jejuni have not declined since 2016 despite the absence of fluoroquinolone use by the poultry industry.

The study confirmed the existence of considerable genetic diversity among the C. jejuni and the C. coli isolates that were collected. Some clonal overlaps were identified across the two surveys, suggesting the persistence of individual clonal groups over the six-year period. This study emphasizes the need for national surveillance programs on Campylobacter spp. to better understand the epidemiology of the pathogen, particularly in the poultry industry. Continuous monitoring is required to manage risks associated with the presence and persistence of resistant strains amongst chicken flocks. Finally, further studies into the persistence of fluoroquinolone resistance in the absence of use will be important to aid secure public health.

Materials and methods

Study design

The samples were collected at slaughter from 20 processing plants that supply most of the chicken meat in Australia (> 90%), in proportion to the number of birds processed at each facility. The design followed the previous Australian study to allow for a direct comparison of findings16. Briefly, 190 samples (pools of five whole cecal pairs) from approximately four to seven-week-old meat chickens were collected at slaughter as part of a structured survey of all major Australian broiler chicken producers undertaken between September 2021 and May 2022. Twenty processing plants representing 95% of national production were sampled, with one cecal pool collected from each processing batch. Only viscera that were not visibly contaminated with digesta were sampled with their intact cecal pair, as per the protocol described by NARMS, USA37.

Each cecal pair was removed from the viscera using sterile scissors at the sphincter between the ceca and the small intestine and one cecum from each cecal pair was placed into a labelled 70 mL sterile screw top container. This continued until each container held a total of five individual ceca from a single processing batch. Each pool of five ceca represented one sample. Consignments of samples were packed with icepacks and dispatched to the Birling Avian Laboratory in New South Wales, Australia, for processing. Any samples that arrived more than 24 h after collection or at a temperature > 8 °C were deemed unacceptable and discarded. In these instances, the collection staff at the processing plant were notified and sent additional sampling kits to collect replacement samples. Only one sample from any single farm being processed on each day of sampling was collected, with duplicate collections from the same farm to be avoided. The exception was for situations were sample numbers required from a processing plant exceeded the number of farms supplying that plant during the study period. In these cases, an additional sample was collected from the farm but from a different batch of chickens.

Bacterial isolation and identification

Campylobacter spp. were isolated as per the AS 5013.6–2015 method38 using Campylobacter selective Bolton broth (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Each pooled sample (five ceca per pool) was homogenized in another container, and the cecal homogenate was added to Bolton broth at a 1:10 ratio and shaken on a rotator (Compact Digital Mini Rotator, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 180 rpm for 3 min. For samples that were < 12 h post-sampling, 100 µl was streaked directly from Bolton broth/homogenate onto CSK (Skirrow, BioMerieux) and CFA (Campy Food Agar, BioMerieux) agar and incubated at 42 °C for 48 h under microaerophilic conditions. For samples that were > 12 h post-sampling, the direct streaking method was performed along with a preliminary incubation of the Bolton broth/homogenate sample at 42 °C for 48 h under microaerophilic conditions, prior to streaking onto CSK and CFA agar. At least 3 putative Campylobacter colonies were picked for species identification. If the identification resulted in duplicate species, one strain was randomly retained. However, if different species were identified (e.g., one C. jejuni and one C. coli), both non-duplicate strains were kept for further analysis.The Campylobacter isolates were speciated using VITEK 2 (BioMerieux) followed by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS; Bruker Biotyper Microflex; Bremen Germany) at the Antimicrobial Resistance and Infectious Diseases Laboratory, Murdoch University, WA, Australia, as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Each bacterial suspension was streaked onto Columbia sheep blood agar (CSBA; Edwards Group) and incubated microaerobically for 24 h at 42 °C. A single colony was selected and streaked onto a second CSBA plate and incubated microaerobically for 24 h at 42 °C. Antimicrobials were prepared on a robotic antimicrobial susceptibility platform using the method of Truswell, et al.39, while antimicrobial sensitivity testing was conducted using the broth microdilution method according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute40. The MIC results were captured using the Vision System (Trek; Thermo Scientific). Isolates were tested against eleven antimicrobials (Merck), namely azithromycin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, florfenicol, gentamicin, nalidixic acid, streptomycin, tetracycline, and telithromycin, using C. jejuni isolate ATCC 33,560 as a control. Results were interpreted using the epidemiologic cut-off values (ECOFF) recommended by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST, https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints). Isolates categorized as non-wild type or wild type were recorded as resistant or susceptible, respectively. Isolates resistant to three or more classes of antibiotics were categorized as being MDR41.

DNA extraction and library Preparation

DNA extraction was performed on 123 C. jejuni and 63 C. coli isolates using the MagMAX Multi-Sample Kit (Thermofisher Scientific, USA), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Library preparation was conducted using a Celero DNA-Seq library preparation kit (NuGEN-Tecan), while library preparations were sequenced via the Illumina Nextseq platform with a 300 cycle High Output Reagent Kit.

DNA sequencing and analysis

Sequencing was carried as described by O’Dea, et al.42, and the genome sequences were de novo assembled using the Unicycler pipeline. Bacterial species were identified using Barrnap (https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap) and Kraken (https://anaconda.org/bioconda/kraken).Assembled genomes were investigated for their STs using the multilocus sequence typing (MLST) tool (https://github.com/tseemann/mlst), and new STs that were identified using the PubMLST Campylobacter jejuni/coli scheme (https://pubmlst.org/bigsdb? db=pubmlst_campylobacter_seqdef) were deposited in PubMLST. AMR determinants and their corresponding mutations were identified via AMRFinderPlus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens/antimicrobial-resistance/AMRFinder/). Relationships between the STs were investigated through the construction of a mid-point rooted phylogenetic tree based on core single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) analysis of the strains. This was as carried out using Snippy (available from https://github.com/tseemann/snippy), with subsequent filtering for putative recombinations using Gubbins (available from https://github.com/nickjcroucher/gubbins) and a phylogenetic tree was generated with IQTree option in Gubbins. Graphical visualization of the phylogenetic tree generated was performed via the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) (https://itol.embl.de/).

Data analysis

MIC data were processed using custom scripts for converting plate reader output into MIC tables. Proportions of colonies with traits of interest and the corresponding 95% exact binomial confidence intervals were derived using the Clopper-Pearson method. All analysis was performed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). The Chi-square test with Yates correction was used to compare differences in resistance rates between species, and between isolates from the current and the previous Australian survey16.

Data availability

All the datasets used during the study are available from the corresponding author of the manuscript on reasonable request and Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information with the BioProject ID: PRJNA1207248 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1207248).

References

Humphrey, T., O’Brien, S. & Madsen, M. Campylobacters as zoonotic pathogens: a food production perspective. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 117, 237–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.01.006 (2007).

Wagenaar, J. A., French, N. P. & Havelaar, A. H. Preventing Campylobacter at the source: why is it so difficult? Clin. Infect. Dis. 57, 1600–1606. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit555 (2013).

Skarp, C. P. A., Hanninen, M. L. & Rautelin, H. I. K. Campylobacteriosis: the role of poultry meat. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 22, 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2015.11.019 (2016).

Cribb, D. M. et al. Risk factors for campylobacteriosis in Australia: outcomes of a 2018–2019 case-control study. BMC Infect. Dis. 22, 586. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07553-6 (2022).

Kaakoush, N. O., Castano-Rodriguez, N., Mitchell, H. M. & Man, S. M. Global epidemiology of Campylobacter infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 687–720. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00006-15 (2015).

EFSA & ECDC. The European union one health 2019 zoonoses report. EFSA J. 19, 1–286. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2021.6406 (2021).

Devi, A., Mahony, T. J., Wilkinson, J. M. & Vanniasinkam, T. Antimicrobial susceptibility of clinical isolates of Campylobacter jejuni from new South Wales, Australia. J. Glob Antimicrob. Resist. 16, 76–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2018.09.011 (2019).

EFSA. The European union summary report on antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2021–2022. EFSA J. 22, 1–195. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2024.8583 (2024).

Price, L. B., Lackey, L. G., Vailes, R. & Silbergeld, E. The persistence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter in poultry production. Environ. Health Perspect. 115, 1035–1039. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.10050 (2007).

Rodrigues, J. A. et al. Epidemiologic associations vary between Tetracycline and fluoroquinolone resistant Campylobacter jejuni infections. Front. Public. Health. 9, 672473. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.672473 (2021).

Sproston, E. L., Wimalarathna, H. M. L. & Sheppard, S. K. Trends in fluoroquinolone resistance in Campylobacter. Microb. Genom. 4 https://doi.org/10.1099/mgen.0.000198 (2018).

Caron, K. et al. The requirement of genetic diagnostic technologies for environmental surveillance of antimicrobial resistance. Sens. (Basel). 21 https://doi.org/10.3390/s21196625 (2021).

WHO. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. 1–28. (2015).

WOAH. OIE Annual Report on Antimicrobial Agents intended for Use in Animals Better understanding of the global situation. 1-136. (2021).

FAO & Drivers Dynamics and epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance in animal production. 1–68 (2016).

Abraham, S. et al. Emergence of fluoroquinolone-Resistant Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli among Australian chickens in the absence of fluoroquinolone use. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 86 https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02765-19 (2020).

Miflin, J. K., Templeton, J. M. & Blackall, P. J. Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolated from poultry in the South-East Queensland region. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59, 775–778. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkm024 (2007).

Obeng, A. S. et al. Antimicrobial susceptibilities and resistance genes in Campylobacter strains isolated from poultry and pigs in Australia. J. Appl. Microbiol. 113, 294–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05354.x (2012).

Andersen, S. R. et al. Antimicrobial resistance among Campylobacter jejuni isolated from Raw poultry meat at retail level in Denmark. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 107, 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.04.029 (2006).

Wallace, R. L. et al. Molecular characterization of Campylobacter spp. recovered from beef, chicken, lamb and pork products at retail in Australia. PLoS One. 15, e0236889. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236889 (2020).

EFSA & ECDC. The European union summary report on antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2018/2019. EFSA J. 19, 1–179. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2021.6490 (2021).

Alfredson, D. A. & Korolik, V. Antibiotic resistance and resistance mechanisms in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 277, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00935.x (2007).

Unicomb, L. E. et al. Low-level fluoroquinolone resistance among Campylobacter jejuni isolates in Australia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42, 1368–1374. https://doi.org/10.1086/503426 (2006).

de Saraiva, M. S. Antimicrobial resistance in the globalized food chain: a one health perspective applied to the poultry industry. Braz J. Microbiol. 53, 465–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-021-00635-8 (2022).

Piccirillo, A. et al. Multilocus sequence typing of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli to identify potential sources of colonization in commercial Turkey farms. Avian Pathol. 47, 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/03079457.2018.1487529 (2018).

Luo, N. et al. Enhanced in vivo fitness of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter jejuni in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102, 541–546. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0408966102 (2005).

Zeitouni, S. & Kempf, I. Fitness cost of fluoroquinolone resistance in Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni. Microb. Drug Resist. 17, 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1089/mdr.2010.0139 (2011).

Page, W. J., Huyer, G., Huyer, M. & Worobec, E. A. Characterization of the porins of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli and implications for antibiotic susceptibility. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33, 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.33.3.297 (1989).

Shen, Z., Wang, Y., Zhang, Q. & Shen, J. Antimicrobial resistance in Campylobacter spp. Microbiol. Spectr. 6 https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.ARBA-0013-2017 (2018).

Asakura, H., Sakata, J., Nakamura, H., Yamamoto, S. & Murakami, S. Phylogenetic diversity and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter coli from humans and animals in Japan. Microbes Environ. 34, 146–154. https://doi.org/10.1264/jsme2.ME18115 (2019).

ACMF. Surveillance for antimicrobial resistance in enteric commensals and pathogens in Australian meat chickens. 1–73 (2018).

Mossong, J. et al. Human campylobacteriosis in Luxembourg, 2010–2013: A Case-Control study combined with multilocus sequence typing for source attribution and risk factor analysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 20939. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20939 (2016).

Narvaez-Bravo, C., Taboada, E. N., Mutschall, S. K. & Aslam, M. Epidemiology of antimicrobial resistant Campylobacter spp. isolated from retail meats in Canada. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 253, 43–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2017.04.019 (2017).

Linn, K. Z. et al. Characterization and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolated from chicken and pork. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 360, 109440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109440 (2021).

Griggs, D. J. et al. Incidence and mechanism of ciprofloxacin resistance in Campylobacter spp. isolated from commercial poultry flocks in the United Kingdom before, during, and after fluoroquinolone treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 699–707. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.49.2.699-707.2005 (2005).

Pratt, A. & Korolik, V. Tetracycline resistance of Australian Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55, 452–460. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dki040 (2005).

FDA. National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System – Enteric Bacteria (NARMS): 2007 Executive Report. 1-102. (2010).

Australia, S. Food microbiology Examination for specific organisms. 1–82 (2015).

Truswell, A. et al. Robotic antimicrobial susceptibility platform (RASP): a next-generation approach to one health surveillance of antimicrobial resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 76, 1800–1807. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkab107 (2021).

CLSI. Methods for antimicrobial Dilution and disk susceptibility testing of infrequently isolated or fastidious bacteria. CSLI Guideline. M45, 1–120 (2016). 3rd ed.

Magiorakos, A. P. et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 268–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x (2012).

O’Dea, M. et al. Antimicrobial resistance, and public health insights into Enterococcus spp. From Australian chickens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 57 https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00319-19 (2019). Genomic.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted with financial support from the Australia Chicken Meat Federation. We acknowledge the assistance of Birling Avian Laboratories, NSW, and the Antimicrobial Resistance and Infectious Diseases Laboratory, Murdoch University. We also appreciate the Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship and Murdoch University for sponsoring Nikki Owiredu’s PhD study.

Funding

This work was funded by the Australian Chicken Meat Federation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation, Methodology; Writing—original draft; N.O., R.A., D.J. and S.A, Supervision- R.A., S. A., and H. S. A.; Data Analysis; N.O., R. A., M.S.; D.H., S.S.L., S.A.; Writing—review & editing, N.O, S.S.L, K.L., R.A, S.A., D.J., D.H.; Funding Acquisition: S.A. and K.H; Resources: D.J., S.S and A.P.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics Declaration

K.H was employed by Australian Chicken Meat Federation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Owiredu, N., Lean, S.S., Stegger, M. et al. Antimicrobial resistance and genomic characteristics of Campylobacter spp. From Australian meat chickens with A follow up investigation. Sci Rep 15, 10780 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94453-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94453-9