Abstract

Ultrasonication (US) is a promising non-thermal technique widely applied in the food sector for improving the extraction process and preserving nutrients. Kinnow fruits have yields of 40–60% juice; the rest of the parts are discarded as waste. The study explored ultrasonication (US) as a pre-treatment to improve juice expression and preserve heat-sensitive nutrients such as vitamin C. The optimization of US treatment was done by varying treatment time (30–90 min) and temperature (30–70 °C) using response surface methodology (RSM). Under optimal conditions, juice yield increased by 14.52% with 4.34% vitamin C loss. The artificial neural network (ANN) model (2-9-1 for yield and 2-10-1 for vitamin C) outperformed the RSM in terms of fitting, predictive ability and accuracy. The kinetic study further indicated that longer US treatment enhanced the total soluble solids (TSS), total phenolic content (TPC), and total color change (ΔE), whereas antioxidant activity and vitamin C content decreased. The yield followed an inverted parabola trend during the kinetic study; yield increased with a k-value of 0.0582 until 30 min and then declined until 60 min with a 0.0253 k-value. These results suggested that US technology has the potential to improve juice yield and maintain nutritional quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Citrus fruits are known for their rich content of minerals, vitamins, good fibers and bioactive components worldwide. USA, Brazil, Mexico, China, Iran, India, Spain, and Greece are the top contributors to Citrus fruit production1. According to the Department of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare2, the annual production of citrus fruits, mandarin, sweet orange and other citrus varieties was recorded at 1,48,10,000 MT and cultivated across 10,95,000 hectares during the 2021–22 period. The common citrus varieties that are cultivated in India are Kinnow, Mosambi, orange, lemon, grapefruit, lime, tangerine and galgal. These fruit varieties are mainly grown in the Southeast Asia region3. Kinnow is a high-yield mandarin hybrid and is extensively cultivated in Punjab, India, with an annual production of 1.2 million metric tonnes. However, during the peak harvest season, saturation in the market leads to reduced prices and forces farmers to discard the surplus produce, mainly by disposing of it in the open, which poses the environment. The limited shelf-life of Kinnow intensifies this issue, which highlights the urgent need for processing solutions to extend its usage and lesser postharvest losses.

Kinnow fruit comes under the ‘Mandarin’ group of the citrus family and is mainly grown in India and Pakistan. Kinnow is a hybrid of two citrus fruits, Citrus nobilis × Citrus deliciosa4, and comes under the Rutaceae family1. The fruit is majorly grown in the Northern states of India like Punjab, Rajasthan, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh5. ̌It is golden orange in color and is sweet and slightly acidic with a rich flavor, available from mid-December to mid-March6. Juice sacs, peels, and seeds are the main parts of the fruit7. The presence of vitamin C and B complex, a rich source of fibers, β-carotene, calcium, and phosphorus, its pleasant color and tangy, sweet, sour, and tart flavor grab the attention of consumers along with food and pharmaceutical industries8. Fruit also contains antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, anti-fungal, carotenoid, and many bioactive compounds like naringin and limonin, which have numerous health benefits9. The fruit can also fulfill the daily increasing demand for functional foods10. Figure 1. provides different aspects of Kinnow as a functional food.

However, the fruit has a limited postharvest shelf-life of approximately 5 days when stored at ambient conditions (11–19 °C and 65–70% RH). Whereas, shelf-life can be increased significantly up to 30 days when stored under cold storage conditions (5–7 °C and 90–95% RH)11. The fruit has 25–30% harvest and post-harvest losses12. Hence, processing should be done to avoid such losses. The fruit is preserved as juices and concentrates. The yield of fruit juice varies from 40% (manual pressing) to 60% (mechanical juice extraction)5, and the collected pomace is discarded as waste. It is worth noting that pomace still contains a considerable amount of juice entrapped in the complex structure of the juice sac. So, achieving a maximum yield of juice during the expression process is one of the main challenges that need to be addressed. Numerous studies have been reported in the literature for enhancing the yield of fruit juices using novel processing methods such as pulsed electric field used for orange and lemons13, hot water bath14 and enzymes for pummelo15, and enzymatic treatment combined with US-assisted expression for noni fruit16.

The US has emerged as a promising non-thermal technology for enhancing the yield while preserving the heat-sensitive components. The method is superior to other techniques like thermal and enzymatic treatment owing to its non-thermal and economical nature, respectively. Moreover, the method does not require any inactivation of enzymes. The primary mechanism behind the US is acoustic cavitation, where high-frequency waves propagate through the food product, producing a high amount of energy because of repeated compression and rarefaction, which leads to the formation, growth, and ultimately collapsing of the bubbles, also known as cavitation17. The heat-labile constituents are also preserved as the temperature is not raised.

Figure 2 illustrates the cavitation phenomenon in the US. Besides, this method has been rarely discussed without enzymatic treatment for increasing the juice yield.

The US plays an important role in improving the availability of key nutritive compounds while preserving components that are heat-sensitive, such as phenols, vitamin C and anthocyanins, thereby balancing the functional and sensory attributes of the juices18. Additionally, the US is found to be effective against microbial load, achieving a 5 log colony forming unit/ mL, which ensures that the safety standards are met19. However, excessive cavitation during the process can result in oxidation and degradation of certain components, which can affect the overall quality. To avoid these effects and maintain the product quality, it is necessary to optimize the operating parameters, such as US power, temperature, and treatment time, is necessary to balance the nutritional retention, microbial inactivation, and overall juice quality18. The application of US not only helps in improving the juice yield but also can decrease the microbial load, therby increasing the yield and increasing the shelf-life.

The study addresses the gap in research regarding the optimization of US as a pre-treatment for KFJ expression without the applications of enzymes. With the main focus on enhancing juice yield and preserving heat-sensitive nutrients, the findings aim to contribute to sustainable food processing methods that can improve the market value of Kinnow and reduce post-harvest losses. Additionally, a kinetic study was conducted under optimized conditions to evaluate the effect of treatment time on various parameters, namely yield, TSS, TPC, AA, and vitamin C. Furthermore, modeling techniques such as RSM and ANN were used for the experimental analysis.

Materials and methods

The present study was carried out in the Department of Food Engineering and Technology, Institute of Chemical Technology – Indian Oil Campus Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India, to increase the juice yield. All chemicals used for experimental purposes were lab-grade. The full forms of all abbreviations used in the article are listed in Table 7.

Procurement of fruit

The fruits were procured from the local orchard of Abohar, Punjab, India. Kinnow’s, a 10–12 cm diameter and a golden orange color, were selected for the experiment.

Pre-treatment of kinnow fruit

The fruits were washed with the help of chlorinated water (100 ppm), followed by washing with potable water and air drying20, and stored at 4 °C until further experiments were carried out.

Juice expression

The fruits were peeled, and the albedo was removed manually. The juice was extracted with the help of a multifunctional food processor (Bajaj Electricals Limited, Model: FX11 600 Watts Food Processor); after expression, the juice was filtered thrice through double-folded muslin cloth to avoid larger particles such as pulp and seeds (as illustrated in the graphical abstract). The juice was further centrifuged (Remi, Neya 16R, India) at 10,000 rpm for 5 min to prepare it for chemical analysis.

US water bath

US treatment was performed using a water bath (Aczet Pvt. Ltd., Model: CUB 5) operating at a frequency of 40 kHz and 120 W power. A sample of 100 g juice sacs was placed inside a container for treatment. The water bath was maintained at a constant temperature with 2.5 L of water throughout the treatment. The temperature was maintained through the regular circulation of water at the desired temperature and by using the automated heater system to regulate the temperature fluctuations.

Experimental design and optimization

The trials were designed based on this preliminary work. The effect of temperature and time on the increase in yield (%) and loss of ascorbic acid percentage was considered. The lower limit for the time and temperature was 30 min and 30 °C, respectively, whereas the upper limit for the time and temperature was 90 min and 70 °C. Design Expert Software (DX-13) from Stat-Ease, a commercial statistical package, was used for experimental design and optimization. Table 1 presents the actual and coded values for the independent parameter used during the US treatment. The Rotatable central composite design (RCCD) was selected. The experiment consisted of 13 factorial runs, including five levels of the two independent variables: time and temperature.

Artificial neural network

Artificial neural network modeling

Different ANN models were developed and tested by using MATLAB software (R2018a, MathWorks, USA) to validate the responses obtained from RSM, i.e., % increase in juice yield and % loss of vitamin C. The ANN surface has an input, output and hidden layer, which was constructed using a feed-forward topology. The input layer had two input nodes, i.e., time and temperature for US treatment (independent parameters) and two output variables, i.e., % increase in juice yield and % loss of vitamin C (Fig. 3).

For this particular study, Tansig was used for the network transfer function, and the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm (LMA) was employed for the training function. It is worth noting that a few neurons can result in underfitting, while too many neurons in the hidden layer result in overfitting as well as prolonged training time. For identifying the optimal network performance, the number of neurons in the hidden layer was estimated by trial and error. The number of neurons varied from 1 to 20. Before subgrouping into testing, validation and training, the experiment data were shuffled. The dataset for ANN modeling contains 13 records per unit variable, which is limited by the collection of experimental data. To address these limitations and ensure robust model evaluation, a k-fold cross-validation approach was used, which divides the data into 70% used for model training, 15% for validation to fine-tune the hyperparameters and the rest of the 15% for independent testing. The approach ensured that every data was used for both training and testing across the folds, which attenuated the issue of limited data and enhanced the reliability and predictive accuracy of the model. Both the models, i.e., RSM and ANN, were compared to find better predictive responses, fitting and accuracy21.

Comparison between RSM and ANN models

Mean square error (MSE), root mean squared error (RMSE), and coefficient of regression (R2) were the different statistical indices that were used to evaluate the ANN model performance22. MSE, RMSE and R2 were calculated using Eqs. (1), (2), and (3)

where n is the observation number, Yi is the predicted output variable for the ith observation, and Ŷi is the experimental output variable for the ith observation.

Kinetics modeling of juice yield and other quality parameters

The kinetic study of the sonication was studied from 10 min, the lowest level, to 60 min, the highest level. During US treatment, the temperature was kept constant at 30 °C to prevent the degradation of bioactive components. The parameters analyzed after the US were yield, ΔE, TPC, TSS, vitamin C, and AA. All the parameters were calculated as a percentage and compared with the control sample to assess the effect of sonication on the quality of juice.

Yield

Juice yield was analyzed with the help of equation (4).

Vitamin C

Vitamin C was determined by the juice’s ability to decolorize the 2,6-dichlorophenol-indophenol (DCPIP) dye, measured spectrophotometrically at 518 nm23,24. The juice samples were diluted (1:10) with 2 % metaphosphoric acid. A reaction mixture of 1 mL of sample extract and 2 mL of DCPIP dye was incubated for 15–20 s, and absorbance was recorded. Vitamin C was expressed as milligrams of ascorbic acid per 100 mL juice.

Antioxidant activity

The sample’s AA was estimated with the help of a methanolic extract of juice, 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), which was used as a reagent25. Trolox was used to prepare the standard curve, absorbance at 517 nm was measured in triplicate, and the average value was reported. AA was expressed in the form of mmol Trolox equivalent/ mL.

Total phenolic content

The total phenolic content of the sample was measured spectrophotometrically with the help of the Folin–Ciocalteau method as suggested by Motikar, More26 with slight modifications, 0.5 mL of diluted juice sample was added to 0.5 mL methanol, followed by 0.5 mL of FC reagent and 3.5 mL of 20% Na2CO3. The mixture was vortexed and incubated for 20 min in the dark. Absorbance was recorded at 735 nm. TPC was calculated as the mean of three replicates, and an average value was reported. TPC was expressed in milligrams of gallic acid per 100 mL of juice sample.

Total soluble solids

The hand-held portable refractometer estimated total soluble solids content in °Brix (Model: Erma RHB-32ATC Brix 0–32%; Make: Japan)27.

Overall color change

The color analysis of the juice was performed according to the method suggested by Chakraborty, Rao28. The color was measured with the help of the CIELAB method, which includes three parameters: L*(lightness), a* (red to green), and b* (yellow to blue). The colorimetric values of the juice were analyzed using Spectra Scan 5100A (Premier Colorscan Instruments India Pvt. Ltd). ΔE was calculated relative to the control sample (untreated juice). ∆E was calculated with the help of the expression given by Eq. (5)

where L, a and b represent the color parameters of the US-treated sample, and L0, a0 and b0 are the color parameters of the untreated juice sample.

Results and discussion

Effect of independent parameters on responses

The estimated effect of independent variables and their interactions on the yield and % loss of vitamin C is presented in Table 2. The absolute values for the juice yield and vitamin C concentration are given in Supplementary Table S1 online. The control sample has a juice yield of 48.08 ± 3.57 mL/100 g of fruit and a vitamin C concentration of 35.65 ± 2.75 mg of ascorbic acid/100 mL.

% Increase in juice yield

The actual values and coded values of the independent variables, along with the responses, are given in Table 3. It can be concluded directly from the ANOVA (Table 3) that treatment time significantly affected the increase in KFJ yield (p < 0.01), whereas temperature showed no substantial impact on juice yield. It was observed that the quadratic model was found to be significant, with an R2 value of 0.915 and a non-significant lack of fit. The relationship between the % increase in juice yield and the independent variable is expressed in the Eq. (6).

where A and B are in the coded form. Y1 is the % increase in juice yield, A is time (in min), and B is the temperature during the process (in °C).

Equation (6) shows that both factors (time and temperature) are antagonistic, signifying that the yield reduces with a simultaneous increase in time and temperature. The trend can be ascribed to the inactivation of enzymes present inherently, like pectinase and pectin methylesterase at higher temperatures. These enzymes play an important role in breaking the cell walls of juice sacs which release the free water and enhance the juice yield. In addition to that, prolonged exposure to sonication resulted in the degradation of enzymes and bioactive components. These factors explained the interaction of time and temperature, resulting in lower juice yield.

Dadan, Grobelna29 observed that the interaction coefficient of time and temperature positively affects the yield of the treatment process in blue honeysuckle berries. However, this trend was not observed in the present study. Because the enzymes got inactivated at higher temperatures, which resulted in losing their functionality. Biz, Farias30 noted a 94% reduction in pectinase activity when the temperature was maintained at 55 °C for 10 min, which favors the impact of higher temperature on the activity of the enzyme. The prolonged exposure to the US resulted in the degradation of bioactive components and other polymers31.

The effect of independent variables, i.e., time and temperature, on the % increase in KFJ yield is depicted in the perturbation plot as well as the response surface (Fig. 4). It was observed clearly from the plot that the treatment time is more effective than the temperature in increasing the KFJ yield. The yield increased when juice sacs were placed in the US water bath for longer durations, whereas shorter durations resulted in significantly less juice. Initially, the temperature affects the yield positively, but this effect decreases with time due to the reasons discussed above.

% Loss of vitamin C

The ANOVA for the % loss of vitamin C is given in Table 3, which depicts that both the time and temperature significantly affected the vitamin C loss, with p-value < 0.01. The temperature adversely affects vitamin C in contrast to treatment time. The R2 value of the model was 0.932, with a non-significant lack of fit. The correlation between the % loss of vitamin C and independent parameters is expressed using Eq. (7).

where A and B are in the coded form, Y2 is the % loss of vitamin C, A is time (in min), and B is the temperature during the process (in °C).

Equation (7) suggests a synergistic impact of time and temperature, as indicated by the positive interaction coefficient. The interaction implies that a simultaneous increase in time and temperature leads to a greater loss of vitamin C. The perturbation graph and response surface (Fig. 5) depict the relationship between the % loss of vitamin C and independent variables. The graphs further confirm that the temperature factor has a more prominent effect on vitamin C degradation than treatment time.

The observed trend could be attributed to the thermal and oxygen sensitivity of vitamin C. Higher temperatures resulted in accelerated degradation of vitamin C through thermal decomposition and oxidation with vitamin C. During the US, cavitation can increase the localized temperature, which further promotes the degradation of vitamin C. In addition to that, prolonged exposure may further intensify this effect, but the effect was less pronounced compared to temperature.

The loss of vitamin C increases when the temperature increases, whereas an increase in treatment time also affects the vitamin C content to a lesser extent, which suggests that vitamin C loss can be reduced when the treatment time and temperature are less. Mieszczakowska-Frąc, Celejewska32 reported vitamin C has lower thermal stability and is easily prone to oxidation when exposed to the environment or air. For instance, when strawberry juice was pasteurized at 85 °C, it resulted in retention of only 65% of vitamin C as compared to the untreated strawberry juice33. Njoku, Ayuk34 also reported a significant decline in vitamin C levels with increasing temperatures in lime, orange, grape, and lemon juice. These findings are in line with the present studies, which emphasize the role of temperature in maintaining the vitamin C concentration during treatment.

Optimization of US-based KFJ expression

After RSM, the numerical optimization was done according to the preference for “minimizing” the % loss of vitamin C and keeping the value of % increase in juice yield "in range." More focus was given to reducing vitamin C loss as ascorbic acid is one of the main factors that needs to be considered for maintaining a nutritional profile. So, comparatively less preference was given to the % yield increase. The relative importance (r) was given to get the desired result and to attain the highest overall desirability value (D). The r values of 5 and 3 were given to % loss of vitamin C and % increase in juice yield, respectively. Higher D values are considered the best fitness for the desired results. The solution with a higher D was selected. The optimum conditions for US-based KFJ expression were 30 min of treatment and 30 °C of US water bath temperature with a desirability value of 0.90. The predicted responses at optimum conditions were a 4.343% loss of vitamin C and a 14.52% increase in the juice yield.

The optimal conditions selected from optimized experiments were verified, performed experimentally, and compared with the data calculated data from the model. The predicted % loss of vitamin C and % increase in the juice yield was 4.343% and 14.52%, respectively. Whereas experimental values for % loss of vitamin C were 4.681 ± 0.268 with 92.779% accuracy, a 15.119 ± 0.416% increase in juice yield was verified experimentally with 96.038% accuracy. Validation of responses at optimized conditions is shown in Table 4.

Artificial neural network

Artificial neural network modeling

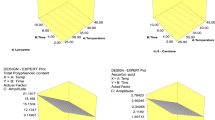

The ANN used a multi-layer feed-forward topology and these were evaluated for the determination of hidden number of neurons. The MSE of the output layer of both responses was plotted against the hidden number of neurons (Fig. 6a). The plot illustrates the impact of hidden neurons on the ANN performance22. The model, which has the lowest mean squared error value and also the highest R-value, was the most effective (2-9-1 for yield and 2-10-1 for vitamin C).

ANN predicted R values for training, validation, and testing of 0.9855, 0.991, and 0.999, and 0.992, 0.954, and 0.997 for yield and vitamin C, respectively (Fig. 6b and c). The figure illustrates the best ANN model prediction for both yield and vitamin C for treatment time and temperature in the US.

Comparison of RSM and ANN models

The comparison between RSM and ANN Models for predictive capability. The comparison for both models was made on the basis of MSE, RMSE, and R2. The values predicted by both the models were tabulated in Table 5.

On comparing the analysis between RSM and ANN for both the responses, i.e., yield and vitamin C, it was clearly observed that ANN showed superior performance. The ANN shows lower values for both MSE and RMSE and higher values for R2, which shows that ANN provides better fitting, more reliable and accurate predictions than the RSM. This could be ascribed to its universal ability to model nonlinear relationships within the system21. On the other hand, RSM is constrained to the approximations of second-order polynomials.

Kinetic modeling of juice yield and quality attributes change

The kinetic study was conducted under optimized conditions. To study the impact of time on the yield and quality attributes, variation in the time was done from 10 min, the lowest level, to 60 min, the highest level, during the US. The other independent variable, temperature, was kept constant because higher temperature leads to a greater reduction in ascorbic acid retention. Yield, total or overall color change, total phenolic content, total soluble solids, vitamin C, and antioxidant activity were analyzed. The data obtained were fitted into the first-order kinetic Eq. (8). The particular k-value was obtained from a logarithmic plot of a specific attribute against time.

where a is any attribute analyzed during the kinetics study, t is the treatment time in min, and k is the first order rate constant in min−1. Kinetic study parameters concerning characteristics are shown in Table 6. The data for the absolute values, kinetic study parameters, and the effect of US treatment time on KFJ quality attributes are presented in Supplementary Table S2 and S3 online, and Supplementary Fig. S1 online.

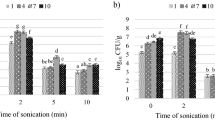

Juice yield of ultrasonicated treated kinnow fruit

The juice yield followed a downward parabola trend (Fig. 7A), which signifies the yield increases intially and later yield decreases as US treatment time increases. The yield rises to a maximum value of 53.27 mL at 30 min from 46.27 mL (control), then decreases to 48.78 mL at 60 min. During the 1st phase (from 10 to 30 min), the yield increased with a k-value of 0.0582 with an R2 value of 0.998 (Fig. 7B). The trend could be ascribed to the release of inherent enzymes like pectinase and polymethyl esterase, which are released due to the disruption of cell walls by ultrasonic cavitation-enhanced juice expression.

However, beyond 30 min, the yield began to reduce with a k-value of 0.0253 (Fig. 7C). Prolonged sonication results in the denaturation of enzymes, which also reduces the effectiveness of breaking down the cell matrix. Similar observations were reported by Tiwari, Muthukumarappan35 reported that PME activity was initially increased, but beyond a certain time limit, the activity of the enzyme reduced. Rodrigues and Fernandes31 also reported that prolonged exposure to ultrasonic waves results in degradation in the concentration of enzymes, vitamins, and other polymers, which are less stable. Nguyen and Nguyen36 also recorded a comparable trend in mulberry juice, where the extraction yield varied from 81.80 to 90.21% at 60 °C under the US, which is higher than pressed juice. The maximum yield of 90.21% was recorded at 60 min but declined to 81.80% when the treatment time reached 120 min.

Kinetics modeling of quality attributes of KFJ

Vitamin C

Vitamin C value was found to be decreased from 37.19 mg/100 mL in the control to 31.72 mg/100 mL at 60 min. Vitamin C concentration decreased with prolonged sonication times at a constant temperature (30 °C) and frequency (40 kHz) (Fig. 7D). The trend likely occurred due to the occurrence of oxidation reactions initiated by free radicals generated during sonication. Thi Thanh Huong, Thinh37 recorded a decrease of 21% in vitamin C levels when the sonication treatment time was extended to 40 min from 10 min at an intensity of 300 W. Ascorbic acid is highly sensitive and unstable and can be easily degraded in the presence of heat, light and oxygen38. Hosseinzadeh Samani, Khoshtaghaza39 and Rawson, Tiwari40 reported similar studies, where prolonged exposure to the US reduces vitamin C levels in sour cherry juice and watermelon juice, respectively, due to oxidative stress.

Total soluble solids

The value of TSS was found to be increased with longer sonication times (Fig. 7E). TSS content showed an increasing trend, increasing from 8.8°Brix in the control sample to 9.8°Brix at 60 min. The TSS value increases at a k-value of 0.0172, with an R2 value of 0.97, indicates a strong relation between sonication time and TSS. The trend could be attributed to ultrasonic waves enhancing the diffusion of bound sugar molecules to permeate from juice sacs to juice, resulting in higher brix values. Nguyen and Nguyen36 recorded an increase of 0.83 units in TSS of mulberry juice when treated with US at 40 kHz and 265 W, with treatment time extended from 0 to 60 min at 60 °C. Manzoor, Ahmad41 also reported an increase in TSS of sugarcane juice by 0.25 units after 40 min of sonication.

Antioxidant activity

AA exhibited a decreasing trend from 179.90 to 148.1 mmol Trolox/100 mL over the treatment time. The antioxidant value decreased with a longer sonication time (Fig. 7F). The reduction of AA occurred at a k-value of 0.0175 and a correlation coefficient of 0.90. This indicates a strong decremental effect of sonication on AA. The trend is attributed to the degradation of polyphenolic compounds by prolonged exposure to sonication due to structural breakdown. Thi Thanh Huonget al.37 reported a 73.44% increase in AA when the sonication time was extended from 10 to 30 min at an intensity of 300W for dried mangoes. Nag and Sit42 reported a decrease in radical scavenging activity for pomegranate peels. Teh and Birch43 observed a decrease in DPPH activity in hemp, flax, and canola seed cakes on prolonged exposure to sonication.

Total phenolic content

The TPC gradually increased from 331.88 to 430.82 mg GAE/ 100 mL juice over time. TPC of KFJ increased (with a k-value of 0.0482) with the increase in sonication time (Fig. 7G). The cavitation resulted in the disruption of cell walls, which released the bound polyphenols into the juice. The improvement in the bioavailability of phenolic compounds is beneficial for human health and appealing to consumers. The formation of hydroxyl radicals during sonication promotes the production of phenolic compounds by attaching them to the aromatic rings. Wanget al.38 and Abid, Jabbar44 also hypothesized the synthesis of phenolic compounds in these conditions. Thi Thanh Huonget al.37 observed an increase of 41.18 mg/100 g in polyphenol content of dried mangoes when sonication time was increased from 10 to 30 min at a power of 300W. Abidet al.44 also reported a 106% increase in the phenolic content of apple juice when treatment time was increased from 30 to 60 min.

Overall color change

ΔE increased from 0.424 at 10 min to 3.008 at 60 min (Fig. 7H). The change in color could be attributed to the destruction of carotenoid pigments, which was caused by cavitation, which induced isomerization and cellular damage to carotenoid pigment. The formation of free radicals during the sonication also accelerates browning reactions, which further alters the color. Cao, Cai45 reported a total color change of 1.11 units in bayberry juice when the ultrasound treatment time increased from 2 to 10 min at an ultrasound intensity of 271 W/cm2. Tiwariet al.35 reported an increase in L* and b* values with a decrease in a* value leading to color change due to prolonged exposure. In addition to that Dias da Silva, Barros46 also observed lycopene degradation during thermosonication of watermelon juice because of prolonged exposure to temperature and time.

Conclusion

The study optimzed the US as a pre-treatment to improve the KFJ yield and minimze vitamin C loss. The optimal conditons chosen were 30 min of US treatment time at 30 °C which resulted in a perdicted vitamin C loss of 4.343% and an increase of 14.52% in juice yield. Experimental validation showed the accuracies of 92.78% vitamin C loss and 96.04% increase in juice yield. The ANN model (2-9-1 for yield and 2-10-1 for vitamin C) have demonstarted better fitting, predictive ability and acuuracy in contrast to RSM. The kinetic study shows that the juice yield increased until 30 min of US, after which it begins to decline with k-value of 0.0253 units. Also, the concentraion of vitamin C and AA decreases over time, whereas ΔE, TSS, and TPC increases with increase in US treatment time. These findings indicate that the efficacy of US pre-treatment in improving the juice yield without compromising nutritional quality. Future research should focus on scaling up this process and assesssing its application to other fruit juice expression. In addition to that, integrating US with other non-thermal technologies, optimizing process parameters for different fruit matrices and long-term stability evaluation will be important to address the current challenges and facilitate the industrial adoption of US as a pre-treatment.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- US:

-

Ultrasonication

- TSS:

-

Total soluble solids

- TPC:

-

Total phenolic content

- AA:

-

Antioxidant activity

- RSM:

-

Response surface methodology

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural networks

- %:

-

Percentage

- °C:

-

Degree Celsius

- Min:

-

Minutes

References

Mahawar, M. K., Bibwe, B., Jalgaonkar, K. & Ghodki, B. M. Mass modeling of kinnow mandarin based on some physical attributes. J. Food Process. Eng. 42(5), e13079 (2019).

Department of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, "Agricultural Statistics at a Glance 2022 ", 2023. Accessed 16 Nov 2024. https://agriwelfare.gov.in/Documents/CWWGDATA/Agricultural_Statistics_at_a_Glance_2022_0.pdf

Gupta, A. K. et al. Current and emerging applications in detection and removal of bitter compounds in citrus fruit juice: A critical review. Food Biosci. 55, 102995 (2023).

Bhattacharjee, A. & Chakraborty, S. Design of a batch Ohmic heater and evaluating the influence of different treatment conditions on quality attributes of kinnow (Citrus nobilis× Citrus deliciosa) juice. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 82, 103186 (2022).

Mahajan, B., Singh, R. & Kumar, M. Quality assurance and shelf-life extension of kinnow mandarin fruit under supermarket conditions. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 16(1), 94–102 (2016).

Ilame, S. A. & Singh, S. V. Physico-chemical properties of ultrafiltered kinnow (mandarin) fruit juice. J. Food Sci. Technol. 55, 2189–2196 (2018).

Kumar, S., Kumar, R., & Sharma, P. De-bittering of kinnow juice (2018).

Bhardwaj, R. & Mukherjee, S. Effects of fruit juice blending ratios on kinnow juice preservation at ambient storage condition. African Journal of Food Science 5(5), 281–286 (2011).

Dua, K. & Kocher, G. S. Fermentative processing of kinnow juice and extraction of limonin from kinnow waste. Curr. Trends Biomed. Eng. Biosci. 4(3), 555637 (2017).

Poonam Aggarwal, S. K. Processing and Value Addition of Kinnow and its By-products 1–15 (Additional Director of Communication for Punjab Agricultural University, 2018).

Mahajan, B., Dhillon, W. & Kumar, M. Effect of surface coatings on the shelf life and quality of kinnow fruits during storage. J. Postharv. Technol. 1(1), 008–015 (2013).

Singh, S. V., Jain, R. & Gupta, A. Adsorptive reduction of naringin from kinnow mandarin juice with non-ionic macroporous adsorbent resin. Indian Chem. Eng. 58(2), 136–156 (2016).

El Kantar, S. et al. Pulsed electric field treatment of citrus fruits: Improvement of juice and polyphenols extraction. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 46, 153–161 (2018).

Ahmad, S., Devi, M., Paul, P. & Bhowmick, N. Study on juice extraction methods for enhancing juice yield and reducing bitterness in pummelo. The Pharma Innovation 10(11), 393–396 (2021).

Ni, H. et al. Pectinase and naringinase help to improve juice production and quality from pummelo (Citrus grandis) fruit. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 23(3), 739–746 (2014).

Wang, S. et al. Effect of combined ultrasonic and enzymatic extraction technique on the quality of noni (Morinda citrifolia L.) juice. Ultrason. Sonochem. 92, 106231 (2023).

Bucur, M. P., Radulescu, M. C., Radu, G. L., & Bucur, B. Cavitation-effect-based treatments and extractions for superior fruit and milk valorisation. Molecules 28(12) (2023).

Roobab, U. et al. An updated overview of ultrasound-based interventions on bioactive compounds and quality of fruit juices. J. Agric. Food Res. 14, 100864 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Influence of ultrasound on the microbiological, physicochemical properties, and sensory quality of different varieties of pumpkin juice. Heliyon 10(6), e27927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27927 (2024).

Hou, W. et al. Investigation on the inactivation effect and mechanism of Listeria monocytogenes in fresh-cut cucumber during storage by ultrasound combined with sodium hypochlorite. Ultrason. Sonochem. 101, 106706 (2023).

Kalsi, B. S., Singh, S., Alam, M. S. & Sidhu, G. K. Comparison of ANN and ANFIS modeling for predicting drying kinetics of Stevia rebaudiana leaves in a hot-air dryer and characterization of dried powder. Int. J. Food Propert. 26(2), 3356–3375 (2023).

Zalpouri, R. et al. Drying kinetics, physicochemical and thermal analysis of onion puree dried using a refractance window dryer. Processes 11(3), 700. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr11030700 (2023).

Bhatkar, N. S., Dhar, R. & Chakraborty, S. Multi-objective optimization of enzyme-assisted juice extraction from custard apple: An integrated approach using RSM and ANN coupled with sensory acceptance. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 45(3), e15256 (2021).

Garba, U. & Kaur, S. Effect of drying and pretreatment on anthocyanins, flavenoids and ascorbic acid content of black carrot (Daucus carrota L.). J. Global Biosci. 3(4), 772–777 (2014).

Nour, V. Quality characteristics, anthocyanin stability and antioxidant activity of apple (Malus domestica) and black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) juice blends. Plants 11(15), 2027 (2022).

Motikar, P. D., More, P. R. & Arya, S. S. A novel, green environment-friendly cloud point extraction of polyphenols from pomegranate peels: A comparative assessment with ultrasound and microwave-assisted extraction. Sep. Sci. Technol. 56(6), 1014–1025 (2021).

Naqash, S. et al. Influence of controlled curing process on physico-chemical, nutritional, and bio-active composition of brown Spanish onion. J. Food Compos. Anal. 114, 104823 (2022).

Chakraborty, S., Rao, P. S. & Mishra, H. N. Effect of combined high pressure–temperature treatments on color and nutritional quality attributes of pineapple (Ananas comosus L.) puree. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 28, 10–21 (2015).

Dadan, M., Grobelna, A., Kalisz, S. & Witrowa-Rajchert, D. The impact of ultrasound-assisted thawing on the bioactive components in juices obtained from blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea L.). Ultrason. Sonochem. 89, 106156 (2022).

Biz, A. et al. Pectinase activity determination: An early deceleration in the release of reducing sugars throws a spanner in the works!. PLoS One 9(10), e109529 (2014).

Rodrigues, S. & Fernandes, F. A. Extraction processes assisted by ultrasound. In Ultrasound: Advances for Food Processing and Preservation, 351–368 (Elsevier, 2017).

Mieszczakowska-Frąc, M., Celejewska, K. & Płocharski, W. Impact of innovative technologies on the content of vitamin C and its bioavailability from processed fruit and vegetable products. Antioxidants 10(1), 54 (2021).

Klopotek, Y., Otto, K. & Böhm, V. Processing strawberries to different products alters contents of vitamin C, total phenolics, total anthocyanins, and antioxidant capacity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53(14), 5640–5646 (2005).

Njoku, P., Ayuk, A. & Okoye, C. Temperature effects on vitamin C content in citrus fruits. Pak. J. Nutr. 10(12), 1168–1169 (2011).

Tiwari, B. K., Muthukumarappan, K., O’Donnell, C. P. & Cullen, P. J. Inactivation kinetics of pectin methylesterase and cloud retention in sonicated orange juice. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 10(2), 166–171 (2009).

Nguyen, C. L. & Nguyen, H. V. H. Ultrasonic effects on the quality of mulberry juice. Beverages 4(3), 56 (2018).

Thi Thanh Huong, N. et al. Effects of microwave and ultrasound treatment on vitamin C, polyphenols and antioxidant activity of mango (Mangifera indica) during low temperature drying. Mater. Today Proc. 59, 781–786 (2022).

Wang, J., Vanga, S. K. & Raghavan, V. High-intensity ultrasound processing of kiwifruit juice: Effects on the ascorbic acid, total phenolics, flavonoids and antioxidant capacity. LWT 107, 299–307 (2019).

Hosseinzadeh Samani, B., Khoshtaghaza, M., & Minaee, S. Modeling the simultaneous effects of microwave and ultrasound treatments on sour cherry juice using response surface methodology. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. (2018)

Rawson, A. et al. Effect of thermosonication on bioactive compounds in watermelon juice. Food Res. Int. 44(5), 1168–1173 (2011).

Manzoor, M. F. et al. Effect of dielectric barrier discharge plasma, ultra-sonication, and thermal processing on the rheological and functional properties of sugarcane juice. J. Food Sci. 85(11), 3823–3832 (2020).

Nag, S. & Sit, N. Optimization of ultrasound assisted enzymatic extraction of polyphenols from pomegranate peels based on phytochemical content and antioxidant property. J. Food Meas. Charact. 12(3), 1734–1743 (2018).

Teh, S. S. & Birch, E. J. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on the polyphenol content and antioxidant capacity of extract from defatted hemp, flax and canola seed cakes. Ultrason. Sonochem. 21(1), 346–353 (2014).

Abid, M. et al. Effect of ultrasound on different quality parameters of apple juice. Ultrason Sonochem 20(5), 1182–1187 (2013).

Cao, X., Cai, C., Wang, Y. & Zheng, X. Effects of ultrasound processing on physicochemical parameters, antioxidants, and color quality of bayberry juice. J. Food Qual. 2019(1), 7917419 (2019).

Dias da Silva, G. et al. Pretreatments for melon drying implementing ultrasound and vacuum. LWT 74, 114–119 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support provided by Nikita Sanjay Bhatkar and Keshram Dulait from the Department of Food Engineering and Technology, Institute of Chemical Technology, Mumbai, ICT-IOC Campus, Bhubaneswar, India (751013).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Vimal Challana: Formal analysis, Software, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Admajith M. Kaimal: Writing –review & editing, Supervision. Shivanand Shirkole: Software, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Akshaya K. Sahoo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Challana, V., Kaimal, A.M., Shirkole, S. et al. Comparative analysis and investigation of ultrasonication on juice yield and bioactive compounds of kinnow fruit using RSM and ANN models. Sci Rep 15, 9859 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94640-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94640-8