Abstract

Small sweeper will become a very popular way to clean roads in cities if its dust removal efficiency could be improved by combining the dust collector of blowing-suction type. A new dust collector of blowing-suction type used in urban cleaning vehicle is presented by this article, which is named W-shaped blowing suction dust collector, and its gas–solid two-phase flow field is numerically analyzed by computational fluid dynamics (CFD) method, including effects of its structural parameters and operating parameters on the dust removal efficiency. It has been demonstrated that the flow field characteristics and the overall dust removal efficiency of the blowing-suction dust collector depend on the diameter-width ratio and the inclination angle of the baffle/slot-shaped nozzle, and the air blowing velocity and the sweeper traveling speed. The optimal combination of structural parameters is the diameter-width ratio of 0.25 and the inclination angle of the baffle/slot-shaped air blow of 69.5°, and the ideal operating parameters are an air blowing velocity of 15 m/s at each port and a sweeper-traveling speed of 1.3 m/s. In the conditions mentioned above, the average near ground velocity of the dust collector is greater than the particle start-up speed of 15m/s and the average velocity of the surrounding air inlet surfaces increases significantly. The negative pressure of the dust collection port is relatively high. Meanwhile, the blowing suction dust collector in this study achieved a dust removal efficiency of over 95%. This study will provide a useful reference for its fabrication followed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The presence of dust and garbage on the road, as well as their flying, harms human health and the city’s appearance1, especially in the rapid urbanization of China2,3,4. This issue can be relieved by using more small cleaning vehicles with high efficiency. The dust removal efficiency of the sweeper vehicle mainly depends on its dust collector, including dust removal method and airflow organization (structure, operating parameters)5.

By incorporating wing plates and side baffles into the pure-suction dust collector, Chen et al.6 reduced the retention time of the dust particles in the dust collector and enhanced the dust removal capability of the sweeper vehicle. WU et al.7,8 involved a gas–solid two-phase flow model in the dust collector to analyze the impact of driving speed, negative pressure and particle size on the dust removal efficiency of a pure-suction dust collector, and the theoretical efficiency is 92%. Zhang et al.9 numerically analyzed the dust removal effect by changing the outside wall around the pure-suction dust collector to a streamlined curved surface. Considering the suspension particle is easier to be captured than the stationary one on the road, the efficiencies of sweeper vehicles mainly depended on the suction method5,6,7,8,9 could be improved by combining blowing and suction method.

For the blowing-suction collector, Jing et al.10 numerically studied the vortex flow effect on pulverized coal removal performance in the fully enclosed blowing-suction collector. With the help of the numerical method, Xi et al.11,12 investigated the impact of the dust collector structure and the airflow distribution of the L-shaped blowing-suction collector on the dust removal performance. Qin et al.13 also proposed an L-shaped blowing-suction dust collector with some make-up air channels and numerically analyzed its dust removal efficiency which is 94.7%. Huang et al.14 conducted an experimental study on the operating parameter and structure impact of U-shaped blowing-suction dust collector on the dust removal efficiency of the small sweeper vehicle, which is 93.28%. Zhang et al.15 proposed a sweeper vehicle with a blowing-suction dust collector for Subway Track and numerically analyzed its structural effect on dust removal performance. Fayzullayevich et al.16 investigated the particle starting speed of a blowing-suction dust collector which has two spouts in both sides and one suction port in central section, and found that the dust removal efficiency could be significantly enhanced by the secondary blowing airflow.

In order to obtain a small sweeper vehicle with better efficiency, this paper provides a new blowing-suction dust collector named W-shaped collector, which has a suction port in the central section and slit shaped nozzles around the perimeter. To optimize the structure and operating parameters of this W-shaped collector, the numerical model and method will be firstly built and verified, and then, the airflow distribution effect on the dust removal performance of the collector will be analyzed, including the suction port diameter, the inclination angle and the blowing velocity of slit nozzle, and the travel speed of vehicle. The paper aims to serve as a theoretical reference for following sweeper vehicle design and fabrication.

Numerical model and method

Physical model

The airflow organization in this paper refers to the parameters of the dust collector domain which could affect the dust collection efficiency of a sweeper vehicle, including the structure of the dust collector, the shape and the air speed of the outlet and the inlet, as well as the resulting velocity field and dust concentration field in the dust collection domain. The airflow organization of the dust collector domain is the key factor on the sweeper vehicle’s performance, whose improvement has been expected.

The sweeper described in this paper mainly consists of the W-shaped blowing-suction dust collector, the dustbin, the filter, the fan, and the vehicle driving system. The dust collector shown in Fig. 1 is square-shaped with a side length of L = 400 mm and a height of H = 44 mm respectively, mainly including the dust collector port in the central section, two air supply ducts, and the air distribution duct, and the slit-shaped nozzle in the surrounding layout.

The W-shaped blowing-suction dust collector. (The figure was created using Microsoft Office Home and Student 2019 https://www.microsoft.com/).

Firstly, the airflow is forced by the fan from both air supply ducts into the air distribution duct, and then, is assigned to the inclined slit nozzle. Secondly, the airflow blows towards the ground to kick up dust particles on the road. Finally, the drifting particle is captured easily by the dust collector port because of its negative pressure effect.

In Fig. 2, D′ refers to the diameter of the dust collector port, while D″ denotes the diameter of the air supply duct. Additionally, the air distribution duct surrounding the dust collector has a width of Wc and a height of Hc. The slit-shaped nozzle has an inclination angle of α and a gap of δ less than 10 mm from the ground to allow external air into the sweeping domain7,9. As a result, the physical model in this paper includes not only the dust collector but also the extended air domain around the dust collector as shown in Fig. 5 ref.7,9,11.

Mathematical model and method

The calculation in this paper is based on the following assumptions: (1) No heat exchange occurs between the inside and outside of the dust collector; (2) The boundary conditions of the dust collector model remain constant; (3) The dust collector moves at a uniform speed; (4) The airflow is incompressible.

Because the turbulent fluid with a high Reynolds number in the scavenging domain happens17, the Reynolds number equations17, Navier–Stokes gas control equations18,19,20, k-ε model19,21, and DPM multiphase flow model are used to predict the airflow and the dust removal performance in the dust collector. The finite volume method and the second-order windward format are used for region and equation discretization.

Turbulence model

The three-dimensional, viscous, incompressible flow in the blowing-suction dust collector can be described by the following equations20,22,23,24,25:

(1) Continuity equation

where ui is the velocity of the fluid in the xi coordinate direction, xi is the coordinate component.

(2) Momentum equation

where ρ is the fluid density, P is the fluid pressure, Tij = −ρui′uj′ is the Reynolds stress, and gi is the gravitational acceleration.

(3) k-ε equation

where k represents the turbulent kinetic energy, μ is the gas dynamic viscosity, ε refers to turbulent dissipation rate, σk denotes the Prandtl-Schmidt number,\(Z_{k} = T_{ij} \frac{{\partial \mathop {u_{i} }\limits^{-\!\!-} }}{\partial xj}\) is the generation term for the turbulent kinetic energy k due to the mean velocity gradient, σk is equal to 1.0, while the constants C1ε, C2ε, and σε represent 1.44, 1.92, and 1.3 respectively9,13,16,21.

Discrete phase model

To describe the gas–solid two-phase flow inside the dust collection domain, the Euler–Lagrange multiphase flow model is used, and the Navier–Stokes equations are used to describe the physical characteristics of the continuous gas-phase flow. The physical characteristics of the discrete-phase particles are described by the DPM (Discrete Phase Model) model11,12. The Lagrangian method is used to track the particle motion, and Newton’s second law provides the equation of motion7,12,26:

where mp is the particle mass, up is the particle velocity, and Fk is the various forces acting on the solid particles. To understand the air–solid two-phase flow within the dust collector, it’s crucial to consider the various forces acting on the particles in the airflow field. These forces include gravity (Fg), lift (Fs), and drag (Fe)10,16,27.

The gravity force acted on the particles is:

The particle in contact with gases inside the dust collector follows the trailing force model27.

where u is the gas velocity, Ce is the coefficient of drag, ρp is the particle density, dp is the particle diameter, and Rep is the particle Reynolds number based on the relative velocities, which is expressed as10,16,28:

The traction coefficient is expressed as follows10,16,28.

When solid particles experience a force, they can move. The expression for this force is as follows10,16.

where q1, q2, q3 are tensor variables and v is the air kinematic viscosity coefficient with constant K = 2.594.

Particle start-up speed

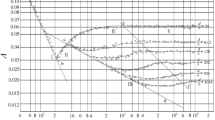

When the airflow velocity exceeds a critical value, the particle on the road starts to move, and even to fly. According to Bagnold’s theory29 and the individual particle initiation velocity of the particle diameter of 10 to 1000μm10,22,30,31,32,33 the initiation velocity can be expressed as Eq. (11).

where Up is the individual particle starting speed, U is the dust particle starting speed, Cf is the drag coefficient, Ar is the Archimedean number, and the Archimedean number is:

According to Bagnold29, the relationship between the particle size and its starting velocity can be described as:

The sweeper provided by this paper is used for the city roads, whose particle size distribution is illustrated in Fig. 3, and so, the particle with a diameter smaller than 10mm is mainly considered in this paper. Figure 4 ref.7,32,33 indicates the minimum starting speed of particles in size of 0-10mm is less than 15m/s, of which, the starting speed of particles in size of 0 to 20μm is nearly constant due to inter-particle viscous forces, that of particles in size of 20 ~ 100 μm decreases with increasing size, and that of particles in size of 0.1 ~ 10 mm increases with particle size acted by buoyancy and gravity. Therefore, in order to firstly fly the dust particles on the city road, a start-up speed of blow air with 15m/s is necessary11,12.

Performance evaluation indicator

In this paper, the overall dust removal efficiency η(dp) shown in Eq. (14) and the graded dust removal efficiency η(dpj) shown in Eq. (15) are used to evaluate the sweeping performance of the dust collector7, respectively.

where Gout and Gin represent the outlet and inlet mass flow rates of dust particles. Gout(dpj) and Gin(dpj) indicate the outlet and inlet mass flow rates of particles of different sizes.

Boundary condition

The dust collector port at the center section is set as the pressure outlet boundary condition, and the slit-shaped nozzle around the dust collector is set as the velocity inlet boundary condition7,16. The gap between the nozzle and ground connecting the dust collection domain and the extended air domain is set as the pressure inlet boundary condition with the standard atmospheric. The dust collector moves at the same speed as the sweeper vehicle7,16.

The particles are discrete-phase and evenly released with zero initial velocity from the 2mm high surface surrounding the dust collector with a 20 mm distance7. When the particle in the dust collection domain moves with the airflow and collides with walls, the “reflect” boundary condition is adopted and its momentum is determined by the restoration coefficient method. When the particles reach the dust collector port, the boundary condition is changed to “trap”, namely all particles at the outlet of the dust collector are captured7. The dust particle at the gap entrance between the nozzle and the ground is set as “escape”, namely the particles are not effectively captured. The Rosin–Rammler model is used for the particle size distribution shown in Fig. 3 ref.7. Table 1 presents the main parameters.

Regional discretization and grid independence assessment

In this article, the finite volume method and the unstructured grid are utilized to discretize the sweeping domain. The result is presented in Fig. 5. The mesh is densified at the dust collector port, the blowing nozzle, and the slit-shaped nozzle. To ensure that the calculation results are independent of the grid number34, several sets of grid systems are first tried to simulate the flow field, and the monitoring indexes include the airflow average velocity at the front, rear, left, and right slit-shaped nozzle of the sweeping domain, the average pressure drop at the dust collector port, and the airflow average velocity at the 4 mm high cross-section of the dust collection domain. The results are shown in Fig. 6. When the grid number is more than 400,000, the relative difference between two continuous results is less than 6%, which indicates the dependence of the calculation result on the grid number could be neglected in the case of this paper23,35. Considering the calculation accuracy and computer resources, the 400,000-grid system will be used for the subsequent calculations.

Grid of blowing-suction dust collector. (The figure was created using ANSYS 2021 R1. https://www.ansys.com/).

Validation of numerical model and method

To verify the numerical method provided in this paper, the same model as that of literature7 shown as Fig. 7 and Table 2 is firstly built, and then, the same evaluating indicators are calculated by the help of the numerical method proposed by this paper. The results calculated by this paper are given in Figs. 8, 9 respectively, which is named Calculated in this.

Pure suction dust collector structure in literature7 (Cited references).

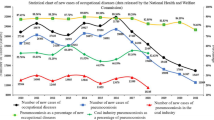

By the test and numerical method, literature7 has conducted a study on the performance of a pure-suction dust collector shown as Fig. 7 and Table 2. Figure 8 gives the test data and the numerical result of literature7 for airflow velocity at different points along the sweeper’s traveling direction on the line (Y = 900mm, Z = 20mm), when the negative pressure inside the dust collector is 2000Pa and the sweeper speed is 10km/h. Figure 9 illustrates three overall dust removal efficiencies of the same dust collector from the test data and numerical result of literature7 at different sweeper speeds respectively. The test data and numeral results of literature7 are named Tested in7 and Calculated in7 respectively in Figs. 8, 9.

It’s clear that the result calculated by this paper is consistent with the experimental data and numerical result of literature7, and the maximum deviation from the experimental data of literature7 is less than 10%, which indicates the numerical method provided by this paper is valid to carry out the numerical calculation of this paper.

Results and discussions

Structural effect of the dust collector

A reasonable structure is the prerequisite for the efficient dust collector. This section will analyze the effect of the dust collector port diameter and the inclination angle of the slit-shaped nozzle on the dust removal performance of a sweeper.

Diameter effect of the dust collector port

The diameter-width ratio id refers to the dust collector port diameter D to the side length L of the dust collector, which will be used to indicate the diameter effect on the flow field of the sweeping domain, the static pressure of the dust collector port, as well as the efficiency of the dust collector, respectively. The numerical calculation results are given in Figs. 10, 11, which are based on the following conditions, 1.3 m/s of the sweeper-traveling speed, 1500 Pa of the fan pressure head, 69.5° of the inclination angle of the slit-shaped nozzle, and 15 m/s of the air speed into the dust collection domain from the slit-shaped nozzle. The other parameters are the same as previously described.

In this paper, 1500 Pa of the fan pressure head is assumed to be constant and equal to the total resistance including the duct system resistance between the fan outlet to the slit-shaped nozzle, the collection domain resistance, and the duct system resistance between the dust collector port and the fan inlet. As seen in Fig. 10, when the diameter of the dust collector port and connected pipe increases, the exhaust air volume increases and the outlet resistance decreases. It results in that, except for the airflow velocity at the collector port, other velocities indicated in Fig. 10, the resistance of the collection domain and the negative pressure at the port increases sharply until 0.25 of id. When id is greater than 0.25, the velocity increase is slowing down and the negative pressure at the port decreases until 0.3 of id. The reason could be that the resistance of the collection domain decreases.

In Fig. 11, the grade efficiency significantly increases as the particle size decreases, especially when id is less than 0.25. Because the airflow velocity increases and the captured distance for the dust particle shortens in the collection domain as id increasing, more and larger particles can be lifted and captured, which results in a significant increase in the overall dust removal efficiency and the grade dust removal efficiency. 0.3 of id could be a critical value to the dust collector discussed in this paper, because the overall efficiency and the grade efficiency decrease when id is between 0.25 and 0.3, especially that of the larger particles, and the grade efficiency is even less than 50% when the particle size is greater than 300 μm. When id is greater than 0.3, both efficiencies increase again.

Based on the above analysis, id of 0.25 is recommended for the dust collector discussed in this article.

Inclination angle effect of the slit-shaped nozzle

To fly the dust particles in the collection domain to nearby the collector port, the inclination angle of the slit-shaped nozzle around the dust collector is the key factor on the dust collection efficiency. Figures 12, 13 illustrate the inclination angle effect of the slit-shaped nozzle on the flow field in the sweeping domain and the dust collection efficiency respectively. All parameters remain the same as before.

In Fig. 12, as the nozzle angle increases to 69.5°, because the air vortices and the air collision are enhanced, the resistance of the collection domain and the negative pressure at the port increase. This leads to the increase in the exhausted air rate at the collector port and the external airflow velocity at the gap inlets. But when the nozzle angle is larger than 69.5°, the reverse situation happens. The reason could be that the less air outside the collection domain enters and the resistance of the collection domain decreases. These findings are consistent with the results of research conducted by Xi et al.11,12.

In Fig. 13, when the nozzle angle increases to 69.5°, the airflow impact effect and its fly dust effect to the dust particle in the collection domain are improved, which results in the significant growth of the collection efficiency, even that of the 425 μm size particle. However, when the nozzle angle is greater than 69.5°, because the less air outside the collection domain enters due to the nozzle airflow obstruction, the situation is reversed and the collection efficiency of the large particle is seriously deteriorated. The difference in the grade efficiency between various size particles is significant when the nozzle angle is away from 69.5°, especially for the large size particle. At 69.5°, the grade efficiencies of all size particles reach the maximum value and the difference between the grad efficiencies is also the minimum.

Based on the above analysis, 69.5° is recommended for the slit-shaped nozzle of the dust collector discussed in this article.

Operating parameter effect of the dust collector

The dust removal performance of the dust collector also depends on the nozzle airflow velocity and the sweeper-traveling speed. This section aims to determine their optimal values.

Blowing velocity of dust collector

Figures 14, 15 show a crucial role played by the airflow velocity from the nozzle on the collector performance.

The nozzle airflow is divided into two streams when it hits the ground, and one blows towards external areas, which will interfere the external airflow into the collection domain. When the airflow velocity at the nozzle outlet increases, the air volume and its interference effect on the external airflow entering the collection domain increase. The average near ground air velocity increases, but the air velocity at the collector port decreases. When the airflow velocity at the nozzle outlet is more than 20m/s, the average near ground air velocity and the air velocity at the collector port all decrease because the interference effect on the external airflow entering the collection domain is enhanced more.

The grad efficiency of the large particle is significantly lower than that of the small particle, especially when the nozzle air velocity is less than 15 m/s. When the airflow velocity at the nozzle outlet increases, because its effect to start dust is improved, the overall removal efficiency increases from 67.1 to 95.5%, and the grade efficiencies also increase, especially for the large particle. When the airflow velocity at the nozzle outlet is larger than 15 m/s, because the air effect to deliver dust decreases due to the decreasing airflow velocity in the collection domain, the overall removal efficiency gradually decreases to 85.9%, and the grade efficiencies are also reduced.

Sweeper-traveling speed of dust collector

In Fig. 16, it can be seen that the pressure drop between the inlet and outlet of the dust collector port remains constant even when the sweeper-traveling speed changes. This means that the total energy supplied by the fan remains unchanged, which does not affect the airflow velocity in the flow field. However, as the sweeper-traveling speed increases, the relative velocity between the dust collector and the dust on the ground also increases. The kinetic energy obtained by the dust particles decreases and the collision angle of the dust particles increases as they move toward the main suction area. As a result, some of the particles leak out of the other surfaces due to inertia, and some of the particles being captured are lowered. Therefore, the overall removal efficiency decreases as the sweeper-traveling speed increases.

In Fig. 17, when the pressure drop remains unchanged, an increase in sweeper-traveling speed leads to a decrease in the probability of a single dust particle being captured. Therefore, when the particle size is the same, the grade efficiency and dust removal decrease with the increase in sweeper-traveling speed. At a certain velocity, smaller particle size dust follows the airflow and is sucked into the middle of the dust collector port, reducing the probability of it escaping from the intake surface. As a result, the grade efficiency decreases with an increase in the size of particles. In conclusion, for better sweeping effect, it is recommended to operate the sweeper at a lower driving speed. However, if the ground dust is less, increasing the speed can improve operational efficiency.

Flow field analysis

Velocity field analysis

The study analyzed the impact of different structural and operating parameters on the internal flow field of the blowing-suction dust collector, aiming to identify the best parameter combination. Figure 18 shows the velocity pattern along the Y direction, with the velocity gradient on the left side of the graph. At Y = 4 mm, the surface velocity was recorded to be around 20 m/s11,12, which was sufficient to create the required starting velocity for dust particles. Additionally, a strong vortex was generated due to the large tangential velocity around the surface, which gradually moved towards the dust collector port with the increase in height. The negative pressure of the port near the outlet attracted the vortex, and in the horizontal section of Y = 32 mm, the airflow from the center to the outside showed an initial increase followed by a decrease.

In Fig. 19, we can see that the outlet of the dust collector has an average velocity of 30 m/s. This speed is sufficient to collect common dust on the road surface to a certain extent. The velocity distribution is symmetrically distributed in both the X = 0 cross-section and the Z = 0 cross-section. The gas enters the dust collector from the surrounding air domain. With the help of the airflow from the air distribution duct, a stronger vortex is generated, the airflow is weakened, and the central part of the dust collector due to the combined effect of the surrounding airflow and negative pressure, the central suction pipe velocity increases, enabling the dust to be smoothly sucked away.

Pressure field analysis

In Fig. 20, it can be observed that the blowing-suction dust collector demonstrates a gradient distribution of the internal pressure field during the working process. This distribution helps external gas inflow to drive the internal dust flow and enable smooth absorption. The external gas enters the dust collector’s interior through the surrounding air inlet surface. As a result, the static pressure value inside the extended air domain is 0 Pa, indicating that the boundary conditions are reasonably set according to the actual situation. Moreover, the negative pressure value in the center of the main suction area of the dust collector is the largest, and there is an obvious pressure gradient.

Conclusion

In order to promote the application of small sweeper in cities, a new type dust collector of blowing-suction named W-shaped collector is provided and the effect of structure and operating parameters on its dust removal efficiency are analyzed. The conclusions are drawn as followed.

-

(1)

Based on the experimental data and numerical results of a pure-suction dust collector in literature6, the numerical method used in this paper is verified.

-

(2)

The structural parameters and operating parameters of the blowing-suction dust collector have a direct impact on the flow field characteristics, and then, the dust removal efficiency. The optimal combination of parameters includes diameter-width ratio of 0.25, inclination angle of the baffle/slot-shaped air blow of 69.5°, air blowing velocity of 15 m/s at each port and sweeper-traveling speed of 1.3 m/s.

-

(3)

The sweeper combined the blowing-suction dust collector of W-shape provided in this paper has higher dust removal efficiency. In the condition of optional parameters, the dust removal efficiency of this sweeper will be over 95%.

Data availability

Data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- α :

-

Inclination angle, °

- d:

-

Diameter of the particle, mm

- δ :

-

Height of slit-shaped nozzle, mm

- D:

-

Diameter, mm

- ε :

-

Turbulent dissipation rate

- F :

-

Force

- g :

-

Gravitational acceleration, m/s2

- G :

-

Mass flow rates

- H:

-

Height, mm

- k :

-

Turbulent kinetic energy

- L:

-

Width, mm

- m :

-

Mass, kg

- μ :

-

Dynamic viscosity, N s/m2

- ρ :

-

Density, kg/m3

- P :

-

Pressure, pa

- q :

-

Tensor variables

- σ:

-

Prandtl-Schmidt number

- T :

-

Reynolds stress

- u :

-

Velocity, m/s

- U :

-

Dust particle starting speed, m/s

- v :

-

Kinematic viscosity coefficient, m2/s

- W:

-

Width, mm

- Ar :

-

Archimedean number

- Re :

-

Reynolds number

- x :

-

Coordinate

- ′:

-

Dust collector port

- ″:

-

Air supply duct

- c:

-

Air distribution duct

- i:

-

Fluid

- in:

-

Inlet

- out:

-

Outlet

- p:

-

Particle

References

Li, Q. et al. Numerical investigations of urban pollutant dispersion and building intake fraction with various 3D building configurations and tree plantings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 3524. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063524 (2022).

Chen, Z., Li, B., Jia, S. & Ye, X. Modeling and simulation analysis of vehicle pollution and carbon reduction management model based on system dynamics. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 14745–14759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-23245-9 (2022).

Bhorkar, M. P., Marwade, A., Piprade, S., Khutafale, S. & Gadhave, V. Reduction of particulate matter on road using dust accumulator. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1197, 012025. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/1197/1/012025 (2021).

Chen, T. et al. Acute respiratory response to individual particle exposure (PM1.0, PM2.5 and PM10) in the elderly with and without chronic respiratory diseases. Environ. Pollut. 271, 116329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116329 (2021).

Nguyen, T.-T.-N. et al. Street dust properties and effective control of secondary particle emission from vacuum street sweepers using composite filters. Sep. Purif. Technol. 354, 129065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.129065 (2025).

Zhongji, C. et al. Experimental study on suction mouth of vacuum sweeper. J. Tongji Univ: Sci. Technol. 29(12), 1483–1485 (2001).

Wu, B., Men, J. & Chen, J. Numerical study on particle removal performance of pickup head for a street vacuum sweeper. Powder Technol. 200, 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2010.02.001 (2010).

Wu, B., Men, J. & Chen, J. Improving the design of a pickup head for particle removal using computational fluid dynamics. Proc. Inst. Mech Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 225, 939–948. https://doi.org/10.1243/09544062JMES2487 (2011).

Zhang, Y. et al. Effects of expanding zone parameters of vacuum dust suction mouth on flow simulation results. J. Cent. South Univ. 21, 2547–2552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-014-2210-2 (2014).

Jing, D., Jia, X., Ge, S., Zhang, T. & Ma, M. Numerical simulation and experimental study of vortex blowing suction dust control in a coal yard with multiple dust production points. Powder Technol. 388, 554–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2021.04.067 (2021).

Xi, Y. Parametric design of reverse blowing pickup mouth based on flow simulation. J. Inf. Comput. Sci. 12, 2165–2175. https://doi.org/10.12733/jics20105653 (2015).

Xi, Y., Dai, Y., Zhang, X. & Zhang, X. Prediction of particle-collection efficiency for vacuum-blowing cleaning system based on operational conditions. Processes 8, 809. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr8070809 (2020).

Qin, X., Xiao, Q. & Zhou, F. Simulation analysis of gas-particle flow through the pickup head of a street sweeper and its design improvement. Chin. J. Appl. Mech. 33, 73–79 (2016).

Huang, X., Ye, J. & Xiong, J. Optimized design and test of suction nozzle for small-sized sweeper. Mach. Des. Res. 35(04), 168–172. https://doi.org/10.13952/j.cnki.jofmdr.a4979 (2019).

Zhang, M., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, F. Numerical analysis on blowing-suction cleaning flow field between subway rails. J. Harbin Inst. Technol. (Chin. Ed.) 52, 137–143. https://doi.org/10.11918/201901164 (2020).

Fayzullayevich, J. V., Tan, G., Alex, F. J., Wu, Y. & Agyeman, P. K. Numerical study of factors affecting particle suction efficiency of pick-up head of a regenerative air vacuum sweeper. Processes 10, 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10071252 (2022).

Zhang, X. H., Wang, T. Y., Liu, D. M., Li, W. & Zhao, P. Experiment of cycle-to-cycle variat-ion of in-cylinder flow with variable tumble. Neiranji Gongcheng Chinese Intern. Combust. Engine Eng. 37, 119–125. https://doi.org/10.13949/j.cnki.nrjgc.2016.04.020 (2016).

Zhang, H. et al. Numerical study on the erosion process of the low temperature economizer using computational fluid dynamics-discrete particle method. Wear 450–451, 203269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2020.203269 (2020).

Ren, T., Wang, Z. & Cooper, G. CFD modelling of ventilation and dust flow behaviour above an underground bin and the design of an innovative dust mitigation system. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 41, 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2014.01.002 (2014).

Ismail, John et al. Computational fluid dynamics simulation of the turbulence models in the tested section on wind tunnel. Ain Shams Eng. J. 11, 1201–1209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2020.02.012 (2020).

Ansart, R. et al. Dust emission by powder handling: Comparison between numerical analysis and experimental results. Powder Technol. 190, 274–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2008.04.053 (2009).

Xin, Y., Li, H. & Wu, J. Applications of CFD technique in the flow field analysis of road sweeper. Appl. Mech. Mater. 733, 583–586. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.733.583 (2015).

Cheng, W., Yu, H., Zhou, G. & Nie, W. The diffusion and pollution mechanisms of airborne dusts in fully-mechanized excavation face at mesoscopic scale based on CFD-DEM. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 104, 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2016.09.004 (2016).

Yu, H., Cheng, W., Wu, L., Wang, H. & Xie, Y. Mechanisms of dust diffuse pollution under forced-exhaust ventilation in fully-mechanized excavation faces by CFD-DEM. Powder Technol. 317, 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2017.04.045 (2017).

Yu, H., Cheng, W., Peng, H. & Xie, Y. An investigation of the nozzle’s atomization dust suppression rules in a fully-mechanized excavation face based on the airflow-droplet-dust three-phase coupling model. Adv. Powder Technol. 29, 941–956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2018.01.012 (2018).

Nazif, H. R. & Basirat Tabrizi, H. Development of boundary transfer method in simulation of gas–solid turbulent flow of a riser. Appl. Math. Model. 37, 2445–2459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2012.05.030 (2013).

Wang, H., Sa, Z., Cheng, W., Zhang, R. & Yang, S. Effects of forced-air volume and suction region on the migration and dust suppression of air curtain during fully mechanized tunneling process. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 145, 222–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2020.08.008 (2021).

Chang, P. et al. Minimizing DPM pollution in an underground mine by optimizing auxiliary ventilation systems using CFD. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 87, 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2019.02.014 (2019).

Bagnold, R. A. The Physics of Blown Sand and Desert Dunes (Springer, 1971). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-5682-7.

Cabrejos, F. J. & Klinzing, G. E. Incipient motion of solid particles in horizontal pneumatic conveying. Powder Technol. 72, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-5910(92)85021-M (1992).

Cabrejos, F. J. & Klinzing, G. E. Pickup and saltation mechanisms of solid particles in horizontal pneumatic transport. Powder Technol. 79, 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/0032-5910(94)02815-X (1994).

Kalman, H., Satran, A., Meir, D. & Rabinovich, E. Pi particles. Powder Technol. 160(2), 103–113 (2005).

Rabinovich, E. & Kalman, H. Pickup, critical and wind threshold velocities of particles. Powder Technol. 176, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2007.01.033 (2007).

Guiza, G. et al. Anisotropic boundary layer mesh generation for reliable 3D unsteady RANS simulations. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 170, 103345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.finel.2019.103345 (2020).

Ren, T., Wang, Z. & Cooper, G. CFD modelling of ventilation and dust flow behaviour above an underground bin and the design of an innovative dust mitigation system. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 41, 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1260/1757-482x.6.1.65 (2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: [Wenhe Zhou]; Project administration: [Wenhe Zhou]; Methodology: [Guangmei Dai]; Formal analysis and investigation: [Guangmei Dai]; Writing-original draft preparation: [Guangmei Dai]; Writing-review and editing: [Wenhe Zhou]; Funding acquisition: [Wenhe Zhou]; Resources: [Wenhe Zhou]; Supervision: [Wenhe Zhou]; Data curation: [Guangmei Dai]; Investigation: [Yapeng Jiang];

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, W., Dai, G. & Jiang, Y. Numerical analysis on the airflow organization of a blowing suction dust collector. Sci Rep 15, 10244 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94767-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94767-8