Abstract

Ubiquitin-specific protease 21 (USP21) is a member of the ubiquitin-specific protease subfamily of deubiquitinating enzymes implicated in tumorigenesis and could be a target for anticancer therapy. Remarkably, it has been reported that overexpression and increased activity of USP21 are observed in various types of cancer, which explains the need for its novel small-molecule inhibitors. Plant-based compounds have emerged as promising candidates for therapeutic development due to their diverse biological activities and potential to modulate key molecular targets in disease pathways. In the present study, an integrated virtual screening strategy was adopted using IMPPAT 2.0. database to identify bioactive phytoconstituents that can potentially inhibit USP21. The selected compounds were subjected to physicochemical properties and binding affinity analysis for primary screening against USP21. Pharmacokinetic analysis, PASS evaluation, and interaction studies pinpointed two bioactive phytoconstituents, Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin, as potential candidates against USP21. Further, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for 500 ns were performed to analyze the conformational flexibility and stability of USP21-phytoconstituent complexes. The phytoconstituents were found to form stable protein-ligand complexes with USP21 throughout the simulation time. These findings provide a basis for subsequent research on Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin as promising leads for drug development against USP21 in cancer treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

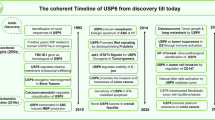

Introduction

Cancer is one of the biggest health challenges to the world today with the incidence and mortality rate rising even with the improvement in diagnosis and treatment1. Conventional treatment strategies such as chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery have enhanced patient prognosis2. However, cancer is a diverse and dynamic disease, and there is a constant need to identify new targets and approaches for effective therapy3. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) has been identified as a relevant system for the regulation of many cellular processes, including protein degradation, cell cycle progression, and signal transduction4. As the major components of the UPS, deubiquitinases (DUBs) have been identified as important modulators of protein homeostasis as their dysfunction is associated with the onset and progression of cancer5.

Ubiquitin-specific protease 21 (USP21) belongs to the ubiquitin-specific protease (USP) subfamily of DUBs, which selectively removes ubiquitin from target proteins to modulate their stability and function6. USP21 has been established to be involved in multiple cellular processes such as immune response, inflammation, and cell differentiation7. USP21 has been described in recent investigations as a factor that enhances tumor growth and survival and can be considered a potential target for cancer therapy8. The overexpression and enhanced activity of USP21 have been reported in many types of cancer, including hepatocellular carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, and so on9. USP21 deubiquitinates and stabilizes oncoproteins such as NF-κB and β-catenin, driving tumor proliferation and metastasis5. Pharmacological inhibition of USP21 restores ubiquitin-mediated degradation of these substrates, triggering apoptosis in cancer cells10. Based on these observations, it can be proposed that the functional inhibition of USP21 could be useful in the treatment of cancer and the enhancement of therapeutic results8.

The effort to explore small-molecule inhibitors targeting DUBs, including USP21, has accelerated in the last few years11,12. Nevertheless, there are several issues to discuss concerning the search for potent and selective inhibitors with suitable pharmacokinetic properties that lack off-target effects13. In this respect, there is increasing interest in natural products, especially bioactive phytoconstituents because of their structural variation and possible pharmacological effects. Plant-derived phytoconstituents have been proven to be a rich source of lead compounds for drug discovery, which possess different pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticancer, etc14. Thus, the investigation of the bioactive phytoconstituents as potential USP21 inhibitors offers a new perspective on cancer treatment using the concept of natural products with a focus on one of the key tumor promotion factors15.

In this study, we have utilized the IMPPAT 2.0 database16 for an integrated virtual screening strategy to find out the bioactive phytoconstituents that can potentially inhibit USP21. IMPPAT is a vast repository of Indian medicinal plants and their phytochemicals16. The first step was to assess the physicochemical properties and the binding kinetics of these compounds to USP21. The USP21-targeted phytoconstituents were then subjected to pharmacokinetics, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation to analyze the stability and the conformational flexibility of the USP21-phytoconstituents complex. We also used the PAINS filter to remove possible false positives and evaluated the ADMET properties for the drug-likeness of the compounds. In the end, we found two phytoconstituents Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin, which showed good binding affinities and pharmacokinetic properties. The PASS analysis also pointed out that these compounds exhibit moderate anticancer effects. By performing 500 ns MD simulations, we found that Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin have competitive binding modes to the USP21 protein and hence could be considered as lead compounds. This work demonstrates the effectiveness of bioactive phytoconstituents as potential inhibitors of USP21 and suggests further experimental confirmation and enhancement of these compounds for cancer treatment. All in all, this study contributes to the therapeutic application of USP21 in cancer therapy and provides a direction toward the investigation of phytoconstituents as promising sources of anticancer drugs.

Materials and methods

Molecular docking screening

The primary database of ~ 18,000 phytochemicals was filtered out on the basis of their physicochemical attributes following the Lipinski rule of five17. Then, the filtered library of 11,908 bioactive phytoconstituents was subjected to an in silico molecular docking process to screen potential small molecules that would have a high binding affinity for USP21. The docking studies were performed using MGL AutoDock Tools18, InstaDock v1.219, PyMOL 3.020, and Discovery Studio Visualizer 202121. The three-dimensional structural coordinates of USP21 were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 3I3T) and optimized for docking studies using InstaDock and AutoDock Tools. Some pre-processing steps were remodeling any missing residues, adding hydrogen atoms to polar sites, and correcting atom typing for accurate docking. Missing residues in the USP21 structure were modeled using Modeller v10.4 embedded in PyMod-3. The remodeled structure was validated using SAVES (https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/), passing in VERIFY 3D and Ramachandran plots (95% residues in favored regions). A total library of bioactive phytoconstituents was generated from the IMPPAT 2.0 database and processed using InstaDock. The docking calculations were performed in InstaDock v1.2 with a grid size set to 79, 65, and 85 Å, with the grid center positioned at coordinates X: 14.508, Y: 19.994, and Z: −34.675. After the compounds had been docked, the compounds of high potential were analyzed based on the binding affinities obtained. Resultant poses were visualized, analyzed for binding interactions, and rendered using PyMOL 3.0.

ADMET prediction

The compounds that passed the docking analysis based on the binding affinities were subjected to the Deep-PK online tool22 to determine their drug-likeness. This tool assessed the ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) profiles based on their chemical structure. Any compound that exhibited a poor ADMET profile was omitted from further study. To further improve selectivity, the PAINS analysis23 was also carried out to remove compounds prone to bind non-specifically to other targets, and the final pool of compounds was specifically targeted to interact with USP21.

PASS prediction and interaction analysis

PASS analysis was used to predict the biological activity spectra of Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin based on structure-activity relationships. The biological activities of the selected compounds were determined using the PASS server, which is based on the comparison of the molecular structure of the compound with the training set containing diverse biological activities24. PASS assesses structure-activity relationships and gives predictions in the form of a ‘probability to be active (Pa)’ and ‘probability to be inactive (Pi)’. The higher the Pa value, the higher the chance that the molecule will be active under the predicted activity. After PASS analysis, further binding interactions and the conformational orientation of the elucidated compounds with USP21 were studied. Interaction analysis of the selected compounds to USP21 was performed and the resulting polar contacts were displayed using PyMOL20. Discovery Studio Visualizer was used to analyze the possibility of interactions within the binding site of the USP21 protein. This approach provided an additional validation layer to prioritize compounds with a high probability of anticancer activity before proceeding to MD simulations. For further analysis, the molecules that interacted with the key residues, especially with the residues at the dimerization interface were chosen for subsequent dynamic analyses.

Molecular dynamic simulation protocol

MD simulations were performed to evaluate the dynamic behavior, conformational changes, and thermodynamics of the protein and protein-ligand complex at an atomistic level. All-atom MD simulations at 300 K were performed on an HP Z840 machine using the GROMACS software25. All the simulations used the GROMOS 96 force field26 for the representation of both the free USP21 protein and the USP21-ligand complexes. The force-field parameters for the ligands Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin were defined, and the topologies of ligand-USP21 were constructed by employing the PRODRG web server27. Each system was solvated in a cubic simulation box with a 10 Å buffer around the system, and the SPC116 water model28 was used to solve the system and maintain an aqueous environment. When required, counter-ions were also introduced to balance the system. The approach to performing the simulation included energy minimization, ligand restraint positioning employing NVT and NPT ensembles in addition to temperature coupling. Finally, MD simulations were run for each system over a 500 ns timescale. The results were subsequently analyzed using GROMACS utilities to assess stability and interactions within the protein-ligand complexes. The plots were generated through XMGrace29 and SigmaPlot 10.030.

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to analyze the conformational flexibility of USP21 in its complexes with bioactive phytoconstituents. The PCA was performed on the trajectory data derived from 500 ns MD simulations of USP21-ligand complexes. All the trajectory files were analyzed using the GROMACS software package. Two major components were extracted as the first two PCs and used to visualize the major conformational changes in USP21 upon binding with phytoconstituents. XMGrace was used to generate PCA plots, where clusters and patterns that suggest significant structural changes were compared.

Free energy landscapes

To study the stability and conformational changes of USP21 in complexes with the selected phytoconstituents, a free energy landscape (FEL) analysis was carried out. Based on the MD simulation, the FEL was determined by applying the potential of mean force (PMF) technique. The analysis was done with the help of GROMACS software, and it was based on the first two PCA components. The FEL plots were constructed to present the energy minima and barriers of various conformations of the USP21-ligand complexes. These plots were employed to assess the binding affinity and stability of the phytoconstituents and to determine the most stable binding modes of USP21.

Results and discussion

Molecular docking screening

Molecular docking intends to estimate the orientation and conformation of a small molecule ligand towards a protein molecule31. We obtained a filtered list of 11,908 phytochemicals from the IMPPAT 2.0 database for this study. By employing InstaDock, the study performed docking simulations of phytochemicals with high binding affinity for USP21. The entire filtered library of 11,908 phytoconstituents was subjected to molecular docking against USP21 using InstaDock v1.2. From this screening, the top ten compounds were chosen according to their docking scores with USP21, as shown in Table 1. The analysis indicated that these compounds had appreciable binding affinities to USP21, with docking scores as low as − 9.3 to − 9.8 kcal/mol. These scores measure the interaction between the ligand and protein, where the lower the score, the better the binding affinity. The selected compounds had better binding affinities than the reference inhibitor BAY-805, with a docking score of − 8.5 kcal/mol. The present study thus points to the possibilities of the elucidated compounds as potential competitors of USP21 binding. It stresses the prospects of these compounds as potential candidates for further development as USP21 inhibitors.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

Pharmacokinetic analysis involving ADMET screening is a valuable approach for evaluating compounds in drug discovery. It is a crucial attribute for assessing the pharmacological potential of a compound for therapeutic development32. ADMET analysis was conducted using the Deep-PK web server while exploiting the SMILES strings of the screened compounds. The ten screened compounds from the docking study were further evaluated for their ADMET properties (Supplementary Table S1). The results showed that a few compounds have good ADMET properties and can be explored for further evaluation. Two compounds, IMPHY001281 (Ranmogenin A) and IMPHY005520 (Tokorogenin), were chosen from the screened compounds based on their ADMET properties and non-carcinogenicity (Table 2). These compounds exhibiting favorable ADMET profiles were prioritized for further assessment. These profiles are characterized by efficient absorption, metabolism, and excretion, lacking toxic patterns. BAY-805, a reference USP21 inhibitor, was included as a positive control. PAINS filtering removed pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS), serving as negative controls. Further evaluation, including biological activity assessment and binding patterns, will provide deeper insights into their potential as therapeutic agents.

PASS analysis

The compounds from the pharmacokinetic screening were subjected to the PASS server to analyze their potential biological activities (Table 3). The study showed that both compounds, Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin, were identified to have high possibilities of stimulating the desired biological activities. The higher the ratio of Pa to Pi, the higher the probability that a molecule will show the expected biological activity. The PASS analysis showed that Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin have potent anticancer activities with considerably high Pa. Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin showed antineoplastic, apoptosis agonist, proliferative disease treatment, chemopreventive, antileukemic, anticarcinogenic, and antiinflammatory biological potential. Both compounds had considerably high Pa values for anticancer activities between 0.608 and 0.907. These results confirm that Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin can be regarded as promising candidates for further analysis and potential use in anticancer drug development.

Interaction analysis

Biomolecular interactions are analyzed to evaluate molecular interactions during drug discovery and development kinetically. The pose selection for the interaction analysis was based on the conformation of the reference compound, BAY-805, and the interaction of the selected hits with USP21. The corresponding docked conformations were chosen so that only those structures with the best match to the crystal structure were considered for further analysis (Fig. 1). The interaction analysis showed that Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin shared a common binding site on USP21 (Fig. 1A). The interaction analysis showed that both Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin interact with multiple residues of the USP21 binding pocket (Fig. 1B). Ranmogenin A’s hydroxyl groups form hydrogen bonds with Gly366 and Cys398, while Tokorogenin’s steroidal scaffold engages in π-alkyl interactions with Tyr362 and Val396. These structural motifs align with known USP21 pharmacophores, suggesting a competitive binding mechanism33. Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin shared the same binding pocket of USP21 as the reference inhibitor (Fig. 1C). Both compounds are involved in conventional hydrogen bonds and other close interactions. These interactions of Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin might potentially inhibit the aberrant activity of USP21 for therapeutic development.

The interaction patterns of both phytocompounds and the reference inhibitor were further analyzed using Discovery Studio Visualizer. From the output files of the chosen compounds, the best conformers for each compound were selected for further analysis. Discovery Studio Visualizer was used to map and further visualize the hydrogen bonding and other interactions between the compounds and USP21. The analysis showed all the non-covalent interactions that occurred between the protein-ligand complexes. Interaction plots of Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin, along with the reference inhibitor BAY-805, were generated (Fig. 2). These plots show that both Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin bind to USP21 similarly to the known USP21 inhibitor. Ranmogenin A showed two conventional hydrogen bonds with Gly366 and Cys398 and five Alkyl bonds with Tyr362 and Val396 (Fig. 2A). It also showed various van der Waals interactions with the USP21 binding site. At the same time, Tokorogenin showed one conventional hydrogen bond with Met358 and one carbon-hydrogen bond with Tyr362, along with eight Alkyl/Pi-Alkyl bonds with four residues of USP21, i.e., Lys307, Met310, Val396, and Cys398 (Fig. 2B). It also showed various van der Waals interactions with the USP21 binding site. The interaction study revealed that both Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin can bind to the binding site of the USP21 enzyme similarly to the reference inhibitor (Fig. 2C). Both elucidated compounds interact with several vital residues in the binding site of USP21. A 3D illustration providing detailed visualization of the functional groups of amino acids interacting with the test compounds, including cases where multiple interactions occur with a single amino acid, is shown in Supplementary Figure S1. These outcomes imply that both Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin have a strong binding to USP21, making them ideal candidates for structure-guided inhibitor development.

MD simulation analysis

MD simulation is one of the most important tools for analyzing the time-dependent properties of molecular systems34. To evaluate the behavior of phytochemicals in the binding site of USP21, we carried out an all-atom MD simulation for 500 ns. To assess the stability of the complex, we considered the various parameters (Table 4). The root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone was employed to measure structural deviations over time, and the root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) to determine the flexibility of the individual amino acid residues. The radius of gyration (Rg) was calculated with the aim of determining the compactness of the protein-ligand complex. At the same time, the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) was computed with the view of determining the changes in the surface of the protein to the solvent. Further, hydrogen bonds were also considered to assess the stability of several interactions between the protein and the ligands. Using PCA, the motions and conformational changes within the system were analyzed. These detailed analyses are useful in providing an understanding of the conformational changes and the stability of the USP21-ligand complexes at different steps of the simulation process.

Structure dynamics

The RMSD of the protein and protein-ligand systems was calculated from the MD simulation trajectories to assess the stability and structural changes in USP21 upon binding with phytochemicals. Throughout the simulation period, the RMSD values for the backbone atoms exhibited minimal variation (Fig. 3A). Initially, the RMSD values increased, but they stabilized after approximately 50 ns of simulation time. When USP21 was bound with Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin, the RMSD values increased at around 50 ns and then remained almost constant at around 3Å for Ranmogenin A and 4Å for Tokorogenin. The average RMSD values of bound conformation of USP21 with Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin and the reference inhibitor BAY-805 were 0.66 Å, 0.62 Å, and 0.55 Å, respectively. In the case of the free USP21, the value was 0.62 Å. These results suggest that the complexes are stable without any significant drift. USP21 showed a similar trend of the RMSD values before and after binding with the selected compounds, indicating that these molecules stabilized the USP21 structure during the MD simulation.

The RMSF of the residues was computed to evaluate the fluctuation of the residues; it quantifies the average displacement of each amino acid from its starting position. This is a measure of the freedom of the amino acids in the protein to move about. In the case of the chosen phytochemicals, the RMSF of amino acids was determined and depicted in Fig. 3B. The RMSF patterns for the residues bound with the elucidated phytochemicals were almost similar, with slight differences. The average RMSF values for free USP21 and its bound states with Ranmogenin A, Tokorogenin, and the reference inhibitor BAY-805 were 0.20 Å, 0.20 Å, 0.19 Å, and 0.18 Å, respectively. These low RMSF values suggest that the amino acids in the protein remained stable during the simulations. This indicates that the protein-ligand complexes are stable, and the binding of the selected phytochemicals did not introduce significant fluctuations in the residues.

Structural dynamics of USP21 with Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin along with the reference inhibitor BAY-805. (A) RMSD plot demonstrates the USP21-Ranmogenin A, USP21-Tokorogenin, and USP21-BAY-805 complexes in the 500 ns simulation. (A) RMSF plot shows the residual fluctuations of USP21 with Ranmogenin A, Tokorogenin, and BAY-805. The lower panels indicate the probability density function (PDF) graphs for RMSD and RMSF values, respectively. Black, orange, aqua and purple represent USP21, USP21-Ranmogenin A, USP21-Tokorogenin, and USP21-BAY-805 values, respectively.

Structure compactness

The Rg is another factor that helps to estimate the folding ability of protein and its density35. It helps to understand the conformational changes of the protein after the binding of the ligand36. From the Rg values, it is possible to estimate the folding kinetics, conformational stability, density, and the three-dimensional arrangement of a protein. In the current work, Rg was used to analyze the compactness of the USP21 protein in its free and ligand-bound forms. At the same time, Ranmogenin A, Tokorogenin, and BAY-805 were included in the simulations (Fig. 4A). Analyzing the Rg plot, it was observed that USP21 was stabilized after the ligand binding and did not experience any significant fluctuations in its stability during the entire MD simulations. The Rg values of USP21 were almost constant before and after the binding of Ranmogenin A, Tokorogenin, and BAY-805, suggesting that the binding of these ligands does not have a substantial impact on the compactness or folding conformation of the protein.

Another parameter that is often employed to analyze protein structure and folding processes is SASA, which reflects the degree of interaction between the protein and the solvent in the given surface area37. SASA, in conjunction with the Rg, gives an understanding of the folding and bonding nature of the protein. In this study, the relative affinity of SASA was determined for the USP21 both before and after the binding of Ranmogenin A, Tokorogenin, and BAY-805. The data obtained revealed stabilization and no significant alterations during the simulation, suggesting that the conformation of USP21 did not change in the presence of these ligands (Fig. 4B). The agreement of the SASA results with the Rg pattern indicates that the folding and dynamics of USP21 were maintained throughout the simulation, and the binding of Ranmogenin A, Tokorogenin, and BAY-805 did not affect the structural stability of the protein. The Rg and SASA values of Apo-USP21 fluctuated slightly more than ligand-bound systems, indicating greater structural compactness upon ligand binding.

Structural compactness of USP21 with Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin along with the reference inhibitor BAY-805. (A) Rg plot demonstrates the USP21-Ranmogenin A, USP21-Tokorogenin, and USP21-BAY-805 complexes in the 500 ns simulation. (A) SASA plot shows the residual fluctuations of USP21 with Ranmogenin A, Tokorogenin, and BAY-805. The lower panels indicate the probability density function (PDF) graphs for RMSD and RMSF values, respectively. Black, orange, aqua and purple represent values for USP21, USP21-Ranmogenin A, USP21-Tokorogenin, and USP21-BAY-805, respectively.

Hydrogen binds dynamics

Hydrogen bond dynamics analysis in MD simulations plays a crucial role in drug discovery by providing insights into the stability and specificity of ligand-protein interactions38. To examine the hydrogen bond dynamics in the protein and the protein-ligand complexes, the ‘gmx bond’ utility in GROMACS was employed, and the distances between receptor-donor pairs were measured at the end of the simulation (Fig. 5). The free protein and all the protein-ligand complexes were used for the analysis, and the study looked at the hydrogen bonds within USP21. The analysis of these results showed that these hydrogen bonds remained almost undisturbed for the entire simulation (Fig. 5A). The consistency in hydrogen bond formation reveals good stability of USP21 and its complexes with the docked ligands, which means that the protein-ligand interactions are stable during the simulation (Fig. 5B). It also indicates that the stability of the protein-ligand complexes could be exploited in USP21 inhibitor development for further drug discovery investigation.

Intramolecular hydrogen bond dynamics. (A) Time-evolution of intramolecular hydrogen bonding in USP21 before and after ligand binding. (B) Probability distribution function (PDF) of intramolecular hydrogen bonds in USP21. Black, orange, aqua and purple represent values for USP21, USP21-Ranmogenin A, USP21-Tokorogenin, and USP21-BAY-805, respectively.

Intermolecular hydrogen bonds are critical in molecular recognition and the strength of protein-ligand interactions38. To evaluate the ability of hydrogen bonding between Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin with USP21, we have analyzed the time profile of these bonds. Ranmogenin A-USP21 and Tokorogenin-USP21 complexes had almost two hydrogen bonds per complex on average (Fig. 6, upper panel). Ranmogenin A forms 1–2 strong hydrogen bonds that may grow up to 4 with considerably less stability (Fig. 6A). Tokorogenin also has 1–2 very strong hydrogen bonds and can have up to 4 bonds with less stability (Fig. 6B). The reference inhibitor BAY-805 also showed to have 1–2 strong hydrogen bonds that may grow up to 6 with less stability (Fig. 6C). The PDF plot indicates that one hydrogen bond was formed with the highest frequency and strength in both systems (Fig. 6, lower panel). The findings of the study showed that both Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin did not move significantly from their starting points regarding USP21. This stability is beneficial in the structural conformation of the docked complexes and the possibility of stable interaction in drug development strategies.

Intermolecular hydrogen bond dynamics in USP21 and (A) Ranmogenin A, (B) Tokorogenin. and (C) BAY-805. The lower panels indicate the probability density function (PDF) graphs for hydrogen bonds. Black, orange, aqua and purple represent values for USP21, USP21-Ranmogenin A, USP21-Tokorogenin, and USP21-BAY-805, respectively.

Principal component analysis

The PCA of MD simulation trajectories can be used to assess the movement and stability of proteins39. PCA was used to analyze their dynamic properties to assess the structural stability of USP21 and its complexes with Ranmogenin A, Tokorogenin, and BAY-805. Figure 7 shows the conformational space of the important regions obtained by the projection of the Cα atoms of these systems. The conformational changes of all four states of USP21 are shown in Fig. 7B using two eigenvectors of the covariance matrix. When the protein is laid out on a 2-dimensional plane, there is some distortion of the conformations of the protein. The graph indicated that the structure of USP21 in complex with Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin has slight fluctuations but lies within the same range as the unbound form (Fig. 7A). However, USP21 in complex with Ranmogenin A showed a slightly different projection on EV2 for some time, shown in orange. Nevertheless, the data illustrate that all four systems are quite similar, indicating that the movement patterns and stability of USP21 are comparable in both the bound and unbound states (Fig. 7B).

Principal component analysis plots. (A) 2D projection of USP21, USP21-Ranmogenin (A), USP21-Tokorogenin, and USP21-BAY-805. (B) Time-evolution projection of USP21, USP21-Ranmogenin A, USP21-Tokorogenin, and USP21-BAY-805. Black, orange, aqua and purple represent values for USP21, USP21-Ranmogenin A, USP21-Tokorogenin, and USP21-BAY-805, respectively.

Free energy landscape analysis

FEL is an important tool to study the folding process of proteins and to evaluate the stability of proteins and their complexes with ligands40. In the present work, FELs were employed to generate energy minima and conformational maps of the USP21, USP21-Ranmogenin A, USP21-Tokorogenin, and USP21-BAY-805 complexes with reference to two PCs that were extracted from the MD simulation trajectories. The FELs of USP21, USP21-Ranmogenin A, USP21-Tokorogenin, and USP21-BAY-805 are shown in the contoured maps of Fig. 8. In these FELs, the regions that correspond to the conformations with low energy levels suggest that the conformation is close to the native state and is depicted in dark blue. The results indicated that Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin binding to USP21 had a negligible effect on the size and position of energy phases, which were placed within 1–2 stable global minima confined within 2–3 basins. The MD simulations and the essential dynamics imply that, in the case of the complex formed by USP21, Ranmogenin A, and Tokorogenin, only slight conformational changes occurred during the 500 ns of simulation. These findings are useful and can be exploited in the development of phytochemical-based small-molecule inhibitors for anticancer therapeutics targeting the aberrant activity of USP21.

Collectively, our integrated computational approach identifies Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin as high-affinity USP21 inhibitors with good pharmacokinetic properties. While these in silico findings constitute a robust basis, experimental validation is essential to validate their therapeutic potential. Future investigations should focus on (i) enzymatic assays to determine USP21 inhibition kinetics, (ii) cytotoxicity screening in multiple cancer cell lines to evaluate antiproliferative activity, and (iii) in vivo validation using murine xenograft models to identify antitumor activity. The bioavailability of these phytoconstituents, which is a critical consideration for plant-derived therapeutics, can be improved by structural optimization of these phytoconstituents, primarily through modifications of functional groups. However, while this study is limited to computational predictions, the convergence of molecular docking, MD simulations and ADMET profiling speaks to the credibility of Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin as lead candidates. Finally, future endeavors must address translational challenges involving scalable synthesis protocols and batch-to-batch consistency, perhaps through advanced formulation strategies like nanoencapsulation or lipid-based delivery systems.

Conclusions

USP21 has been identified as involved in tumorigenesis and is an established drug target for anticancer therapy. Phytoconstituents have been identified as potential therapeutic agents given their multiple biological actions and ability to influence disease-related molecular targets. In this study, we have used a structure-guided integrated virtual screening technique to identify phytochemicals with inhibitory potential against USP21. To assess the interaction and stability of phytoconstituents with USP21, our approach consisted of in silico molecular docking, ADMET predictions, and MD simulations followed by essential dynamics analyses. The study pinpointed two phytoconstituents, Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin, with high binding affinities toward USP21 and appreciable pharmacokinetic profiles. The PASS analysis proved their potent anticancer activity, further supporting their candidacy for anticancer agents. The simulation analyses inferred that both compounds have stable binding potential for the USP21 binding pocket with minimal conformational changes. The data obtained in the present study can be a basis for additional experimental investigation of the anti-USP21 activity of Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin. Overall, this study adds new potential leads to the USP21 targeted therapy and emphasizes the importance of natural products in modern pharmacotherapy. Future studies should synthesize Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin derivatives to enhance potency, validate USP21 inhibition via enzymatic assays, and evaluate antitumor efficacy in murine xenograft models. Furthermore, studies should be directed towards the in vitro and in vivo confirmation of these phytoconstituents to enhance the pharmacological profile and assessment of the therapeutic potential of these phytoconstituents.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J. Clin. 74 (3), 229–263 (2024).

Kaur, R., Bhardwaj, A. & Gupta, S. Cancer treatment therapies: traditional to modern approaches to combat cancers. Mol. Biol. Rep. 50 (11), 9663–9676 (2023).

Roma-Rodrigues, C., Mendes, R., Baptista, P. V. & Fernandes, A. R. Targeting tumor microenvironment for cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (4), 840 (2019).

Park, J., Cho, J. & Song, E. J. Ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) as a target for anticancer treatment. Arch. Pharm. Res. 43 (11), 1144–1161 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Deubiquitinases in cancers: aspects of proliferation, metastasis, and apoptosis. Cancers 14 (14), 3547 (2022).

Gao, H. et al. Targeting ubiquitin specific proteases (USPs) in cancer immunotherapy: from basic research to preclinical application. J. Experimental Clin. Cancer Res. 42 (1), 225 (2023).

An, T., Lu, Y., Yan, X. & Hou, J. Insights into the properties, biological functions, and regulation of USP21. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 944089 (2022).

Shi, Z-Y. et al. The emerging role of deubiquitylating enzyme USP21 as a potential therapeutic target in cancer. Bioorg. Chem. :107400. (2024).

Zhou, P. et al. USP21 upregulation in cholangiocarcinoma promotes cell proliferation and migration in a deubiquitinase-dependent manner. Asia‐Pacific J. Clin. Oncol. 17 (6), 471–477 (2021).

Dagar, G., Kumar, R., Yadav, K. K., Singh, M. & Pandita, T. K. Ubiquitination and deubiquitination: Implications on cancer therapy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. :194979. (2023).

Antao, A. M., Tyagi, A., Kim, K-S. & Ramakrishna, S. Advances in deubiquitinating enzyme inhibition and applications in cancer therapeutics. Cancers 12 (6), 1579 (2020).

Göricke, F. et al. Discovery and characterization of BAY-805, a potent and selective inhibitor of ubiquitin-specific protease USP21. J. Med. Chem. 66 (5), 3431–3447 (2023).

Spano, D. & Catara, G. Targeting the ubiquitin–proteasome system and recent advances in cancer therapy. Cells 13 (1), 29 (2023).

Anjum, F. et al. Phytoconstituents and medicinal plants for anticancer drug discovery: Computational identification of potent inhibitors of PIM1 kinase. Omics: J. Integr. Biology. 25 (9), 580–590 (2021).

Vijayan, Y., Sandhu, J. S. & Harikumar, K. B. Modulatory Role of Phytochemicals/Natural Products in Cancer Immunotherapy. Curr. Med. Chem. (2024).

Vivek-Ananth, R., Mohanraj, K., Sahoo, A. K. & Samal, A. IMPPAT 2.0: an enhanced and expanded phytochemical atlas of Indian medicinal plants. ACS omega. 8 (9), 8827–8845 (2023).

Lipinski, C. A. Lead-and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug discovery today: Technol. 1 (4), 337–341 (2004).

Huey, R., Morris, G. M. & Forli, S. Using AutoDock 4 and AutoDock vina with AutoDockTools: a tutorial. Scripps Res. Inst. Mol. Graphics Lab. 10550 (92037), 1000 (2012).

Mohammad, T., Mathur, Y., Hassan, M. I. & InstaDock: A single-click graphical user interface for molecular docking-based virtual high-throughput screening. Brief. Bioinform. 22 (4), bbaa279 (2021).

DeLano, W. L. & Pymol An open-source molecular graphics tool. CCP4 Newsl. Protein Crystallogr. 40 (1), 82–92 (2002).

Visualizer, D. Discovery Studio Visualizer. 2. Accelrys software inc. (2005).

Myung, Y., de Sá, A. G. & Ascher, D. B. Deep-PK: deep learning for small molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. :gkae254. (2024).

Baell, J. B. Feeling nature’s PAINS: natural products, natural product drugs, and pan assay interference compounds (PAINS). J. Nat. Prod. 79 (3), 616–628 (2016).

Filimonov, D. et al. Prediction of the biological activity spectra of organic compounds using the PASS online web resource. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 50, 444–457 (2014).

Van Der Spoel, D. et al. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 26 (16), 1701–1718 (2005).

Schuler, L. D., Daura, X. & Van Gunsteren, W. F. An improved GROMOS96 force field for aliphatic hydrocarbons in the condensed phase. J. Comput. Chem. 22 (11), 1205–1218 (2001).

Van Aalten, D. M. et al. PRODRG, a program for generating molecular topologies and unique molecular descriptors from coordinates of small molecules. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 10, 255–262 (1996).

Mark, P. & Nilsson, L. Structure and dynamics of the TIP3P, SPC, and SPC/E water models at 298 K. J. Phys. Chem. A. 105 (43), 9954–9960 (2001).

Turner, P. & XMGRACE Version 5.1. 19. Center for Coastal and Land-Margin Research2 (Oregon Graduate Institute of Science and Technology, 2005).

Monks, S. SigmaPlot 8.0. Biotech Software & Internet Report: The Computer Software Journal for Scientists. ;3(5–6):141-5. (2002).

Naqvi, A. A., Mohammad, T., Hasan, G. M. & Hassan, M. I. Advancements in docking and molecular dynamics simulations towards ligand-receptor interactions and structure-function relationships. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 18 (20), 1755–1768 (2018).

Ferreira, L. L. & Andricopulo, A. D. ADMET modeling approaches in drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today. 24 (5), 1157–1165 (2019).

Ernst, A. et al. A strategy for modulation of enzymes in the ubiquitin system. Science 339 (6119), 590–595 (2013).

Shamsi, A., Khan, M. S., Yadav, D. K. & Shahwan, M. Structure-based screening of FDA-approved drugs identifies potential histone deacetylase 3 repurposed inhibitor: molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulation approaches. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1424175 (2024).

Lobanov, M. Y., Bogatyreva, N. & Galzitskaya, O. Radius of gyration as an indicator of protein structure compactness. Mol. Biol. 42, 623–628 (2008).

Hong, L. & Lei, J. Scaling law for the radius of gyration of proteins and its dependence on hydrophobicity. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 47 (2), 207–214 (2009).

Durham, E., Dorr, B., Woetzel, N., Staritzbichler, R. & Meiler, J. Solvent accessible surface area approximations for rapid and accurate protein structure prediction. J. Mol. Model. 15, 1093–1108 (2009).

Bitencourt-Ferreira, G., Veit-Acosta, M. & de Azevedo, W. F. Hydrogen bonds in protein-ligand complexes. Docking screens drug discovery :93–107. (2019).

Tharwat, A. Principal component analysis-a tutorial. Int. J. Appl. Pattern Recognit. 3 (3), 197–240 (2016).

Papaleo, E., Mereghetti, P., Fantucci, P., Grandori, R. & De Gioia, L. Free-energy landscape, principal component analysis, and structural clustering to identify representative conformations from molecular dynamics simulations: The myoglobin case. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 27 (8), 889–899 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the generous support from the Research Supporting Project (RSP2025R352) by King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The authors are grateful to Ajman University for supporting the publication through IRG (2024-IRG-PH-1).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anwar, S., Khan, M.S., Yadav, D.K. et al. Exploring bioactive phytoconstituents as USP21 inhibitors for therapeutic development against cancer. Sci Rep 15, 15625 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94825-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94825-1