Abstract

Neonates with pneumonia (NWP) may experience unidentified life-threatening sepsis, yet distinguishing NWP from neonates with sepsis (NWS) based solely on clinical presentation remains challenging. This study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic utility of the C-reactive protein to platelet ratio (CPR) in distinguishing neonatal late-onset sepsis (LOS) among NWPs. From February 2016 to March 2022, a total of 1385 NWPs aged over 3 days were included. Of these, 174 neonates with confirmed positive blood cultures were categorized into the sepsis cohort, while the remainder formed the pneumonia cohort. All clinical data were retrospectively extracted from electronic medical records. CPR was calculated as the ratio of C-reactive protein levels to platelet count. Independent risk factors (IRFs) for neonatal LOS were identified through multivariate logistic regression. The diagnostic performance of CPR in identifying LOS among NWPs was analyzed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve metrics. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24.0 and MedCalc version 15.2.2. Neonates with NWS demonstrated significantly higher CPR compared to those with NWP alone. Further analysis revealed a notably increased incidence of sepsis among neonates exhibiting elevated CPR levels relative to those with lower values. Correlation analysis identified a direct association between CPR and elevated procalcitonin, creatinine, and urea nitrogen levels, as well as prolonged hospitalization. Multiple logistic regression analysis identified CPR as an IRF for late-onset NWS. ROC curve analysis demonstrated that CPR outperformed CRP and platelet count individually in diagnosing NWS, with a diagnostic sensitivity of 54% and specificity of 85%. CPR serves as an effective initial diagnostic marker with superior accuracy in distinguishing delayed NWS from NWP compared to CRP and platelet count alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Compared to adults, neonates are more susceptible to infections by pathogenic microbes, often resulting in respiratory illnesses or bloodstream infections due to their underdeveloped immune systems1. Neonates with sepsis (NWS) poses a substantial threat to infant health, ranking as the third leading cause of neonatal mortality globally and accounting for 13% of total neonatal deaths2,3,4. Additionally, cases of neonates with pneumonia (NWP) may involve undiagnosed sepsis, and the absence of timely interventions aligned with the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Physician’s guidelines could impede the efficacy of standardized treatment plans5. Differentiating between NWP and NWS remains challenging, as both conditions frequently present overlapping clinical features6. Furthermore, while blood culture is the diagnostic gold standard for NWS, it is time-intensive and demonstrates low sensitivity7. This highlights the need for more efficient and reliable biomarkers to facilitate the early detection of sepsis in neonates.

An acute-phase reactant, C-reactive protein (CRP), undergoes significant elevation during inflammatory processes within the body8. Extensive research has demonstrated strong associations between CRP levels and systemic inflammation9,10,11. Recognized as one of the most studied and clinically relevant biomarkers, CRP plays a key role in the early detection of sepsis, serving as a reliable prognostic indicator and a determinant of adverse outcomes in septic patients12,13. Moreover, CRP exhibits superior screening accuracy for late-onset NWS compared to early-onset sepsis, further establishing its diagnostic utility14. Platelets (PLTs), essential cellular components in the bloodstream, are integrally involved in hemostatic disruption and immunoinflammatory processes during sepsis. Enriched with pro-inflammatory cytokines, PLTs release highly reactive particles and interact with endothelial cells, contributing to microthrombus formation and subsequent organ dysfunction15,16,17,18. Clinical evidence indicates a frequent correlation between sepsis and thrombocytopenia in both adult and neonatal populations19,20,21. The C-reactive protein to platelet ratio (CPR) has emerged as a novel indicator reflecting both inflammatory and coagulation states. However, its clinical applicability in differentiating neonatal late-onset sepsis (LOS) from NWP remains insufficiently defined. This study aims to evaluate the diagnostic potential of CPR in distinguishing sepsis from pneumonia in neonates.

Methodologies and materials

Study design and population

This retrospective single-center observational study, conducted at Henan Children’s Hospital, China, from February 2016 to March 2022, focused on hospitalized NWPs aged 3–28 days admitted through the emergency department. Inclusion criteria were strictly applied, excluding neonates with hematological disorders, malignancies, major congenital anomalies, or incomplete data on body temperature, CRP levels, and PLT counts at admission. Premature neonates (gestational age < 37 weeks) were also excluded. The study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Hospital Ethics Review Board of Henan Children’s Hospital (No. 2024-009). Data collection was retrospective, with strict anonymization protocols ensuring confidentiality. Due to the study’s retrospective design, the requirement for informed consent was waived, as confirmed by the Hospital Ethics Review Board of Henan Children’s Hospital (No. 2024-009).

Clinical definitions

The neonates included in this study all met the diagnostic criteria for neonatal pneumonia22 and determined independently by two physicians based on patients’ medical history, clinical manifestations, and laboratory findings. Key factors evaluated included high-risk conditions for NWP, prior contact with infected individuals, irregular body temperature, cough, respiratory distress, snoring, deviations in peripheral blood immune cells, and inflammatory markers. Additionally, chest X-rays were utilized to detect pulmonary infiltrates, a characteristic feature in NWP cases. Neonatal LOS was defined by the presence of a positive blood culture alongside systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), occurring beyond 72 h post-birth. SIRS diagnosis necessitated meeting at least two of four criteria, one of which was an abnormal temperature or leukocyte count: (1) temperature deviation (> 38.5 °C or < 36 °C), (2) leukocyte abnormalities, (3) tachycardia or bradycardia, and (4) irregular respiratory rate. The criteria were established following the International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus23.

Data collection and laboratory evaluation

The study analyzed clinical and laboratory data extracted from patients’ electronic medical records during hospitalization. Key parameters recorded included age, sex, body weight, body temperature, respiratory and heart rates, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), length of hospital stay, and levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), creatinine (CREA), urea nitrogen (UREA), procalcitonin (PCT), and CRP. Additional hematological measures included white blood cells (WBC) count, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, and PLT count. ALT, AST, CREA, and UREA levels were quantified using standard clinical methods on a Beckman automatic biochemical analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). PCT concentrations were determined via electrochemiluminescence on the Elecsys® BRAHMS PCT platform, with a detection range of 0.02–100 ng/mL (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). CRP levels were measured through a latex-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay with a range of 0.08–320 mg/L (Ultrasensitive CRP kit; Upper Bio-Tech, Shanghai, China). Hematological parameters, including neutrophils, lymphocytes, and PLTs, were evaluated using a Sysmex automated CBC analyzer (Sysmex Corporation, Japan). To address assay detection limits, PCT concentrations exceeding 100 ng/mL or below 0.02 ng/mL were assigned values of 101 ng/mL and 0.01 ng/mL, respectively, while CRP levels under 0.8 mg/L were recorded as 0.7 mg/L. The CPR was calculated as the ratio of CRP (mg/L) to PLT count (× 10⁸ cells/L).

Statistical analysis

Data with normal distributions were expressed as means ± standard deviations and analyzed using independent t-tests or one-way ANOVA, while non-normally distributed variables were presented as medians (interquartile range) and evaluated through the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical data were described as frequencies and percentages and analyzed via chi-square tests. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was applied to determine associations between CPR and other continuous variables. To evaluate CPR’s potential as an early diagnostic marker for distinguishing sepsis from pneumonia, univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were constructed. Variables demonstrating statistical significance (P < 0.05) in univariate analyses were included in multivariate binary logistic regression. ROC curves were generated to evaluate CPR’s diagnostic performance in identifying sepsis within NWP, with the area under the ROC curve (AUC) calculated and compared using the DeLong test. The optimal CPR cutoff point was determined based on Youden’s index (sensitivity + specificity − 1)24. Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS (Version 24.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, URL: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-24) and MedCalc (Version 15.2.2, MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium, URL: https://www.medcalc.org). Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P value of < 0.05.

Results

Study population characteristics

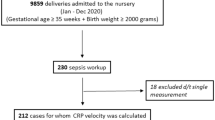

The study included 1385 NWPs who met the defined inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Of these, 174 neonates (12.6%) with positive blood cultures were diagnosed with sepsis and allocated to the sepsis cohort, while the remaining 1211 (87.4%) neonates without sepsis were assigned to the pneumonia cohort. Table 1 outlined the baseline characteristics of the participants. Compared with NWP alone, NWS demonstrated reduced gestational age, body weight, SBP, and DBP, alongside an increased frequency of mechanical ventilation (P < 0.01). Biochemical and CBC analyses indicated significantly higher levels of PCT, CRP, CREA, UREA, WBC, and neutrophil counts in NWS (P < 0.05), whereas lymphocyte and PLT counts were notably lower (P < 0.001). Additionally, CPR levels in NWS were significantly elevated compared with NWP alone (P < 0.001).

Association between CPR levels and the occurrence of NWS

Neonates were stratified into two cohorts based on the median CPR value. The high CPR cohort demonstrated greater age and elevated PCT levels compared to the low CPR cohort (Table 2). Analysis indicated a significantly higher incidence of sepsis in the high CPR cohort compared to the low CPR cohort (18.5% vs. 6.6%, P < 0.001), accompanied by a markedly lower incidence of pneumonia (81.5% vs. 93.4%, P < 0.001).

Association between CPR and clinical parameters

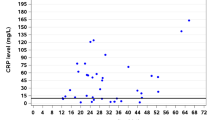

Spearman’s correlation analysis identified significant associations between CPR and various clinical parameters, as shown in Table 3. CPR exhibited inverse correlations with age (r = − 0.204, P < 0.001), body weight (r = − 0.151, P < 0.001), SBP (r = − 0.133, P < 0.001), DBP (r = − 0.083, P = 0.002), and lymphocyte count (r = − 0.388, P < 0.001). Positive correlations were observed with PCT (r = 0.371, P < 0.001), CREA (r = 0.209, P < 0.001), UREA (r = 0.067, P = 0.013), neutrophil count (r = 0.135, P < 0.001), and hospitalization duration (r = 0.188, P < 0.001). No significant correlations were detected between CPR and body temperature, heart rate, ALT, or AST levels.

Independence of CPR levels in identifying NWS

Variables with P < 0.05 identified in the univariate analysis included body temperature, heart rate, SBP, DBP, PCT, ALT, AST, CREA, UREA, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, and mechanical ventilation. Following adjustments for these factors, multivariate analysis revealed that CPR remained an independent predictor of NWS in NWP (odds ratio [OR] = 1.555, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.237–1.954, P < 0.001; Table 4). Additionally, CPR tertiles demonstrated an independent association with an increased likelihood of NWS (OR = 1.764, 95% CI 1.166–2.669, P = 0.007).

Diagnostic value of CPR in NWS

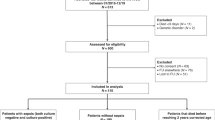

ROC curve analysis was performed to assess the diagnostic efficacy of CPR in differentiating sepsis from pneumonia in neonates. Figure 2 illustrated that the AUC for CPR demonstrated strong diagnostic performance in identifying NWS (AUC = 0.73, 95% CI 0.68–0.78, P < 0.001), exceeding the performance of CRP (AUC = 0.68, 95% CI 0.63–0.73, P < 0.001) and PLT count (AUC = 0.67, 95% CI 0.62–0.72, P < 0.001) (P < 0.05). The optimal CPR threshold for predicting NWS was determined to be 0.054, providing 54% sensitivity and 85% specificity. Based on this threshold, neonates were stratified into two groups: CPR ≤ 0.054 and CPR > 0.054. Table 5 indicated that the CPR ≤ 0.054 cohort comprised 1027 (92.8%) NWP and 80 (7.2%) NWS cases, whereas the prevalence of NWS in the CPR > 0.054 cohort was significantly higher compared to the CPR ≤ 0.054 group (33.8% vs 7.2%, P < 0.001).

Discussion

Neonates are particularly vulnerable to infections due to the immaturity of their physiological systems, with various pathogens capable of inducing NWP1 upon lung invasion. Without timely intervention, NWP may progress to NWS25, characterized by systemic inflammation and multi-organ dysfunction, which significantly impairs neonatal health. NWS remains a leading cause of neonatal mortality and long-term disability, posing a critical global public health challenge26. According to the Global Sepsis Alliance, infection-related sepsis accounts for approximately 20% of neonatal deaths globally27 with sepsis-associated mortality rising to 37.2% during the late neonatal period (7–27 days)28. Early detection of NWS is essential to enable timely intervention, effective treatment, prevention of severe complications, and reduction of mortality5. Blood culture, recognized as the diagnostic gold standard for NWS, is hindered by limitations such as prolonged processing times, low positivity rates due to small blood sample volumes, potential contamination, or prior antibiotic use before hospitalization7,29,30. In contrast, peripheral blood circulation markers offer a more accessible and cost-effective alternative for diagnosis.

From a pathophysiological standpoint, sepsis is characterized as a systemic hypermetabolic inflammatory condition, with inflammatory cells and cytokines playing a central role in its progression31,32. Among these cytokines, CRP serves as a traditional biomarker that demonstrates significant elevation in response to inflammation, particularly during bacterial infections33. In the context of sepsis, CRP has been extensively validated as a prognostic marker and a contributing factor in both adult and neonatal sepsis13,34,35. However, its specificity is limited by physiological elevations following birth and increases linked to non-infectious conditions36,37. PLTs, specialized blood components essential for hemostasis and thrombosis38, have emerged as key players in immune regulation. They are now recognized for their capacity to activate other immune cells and promote the generation of coagulation factors and inflammatory cytokines39,40,41. Research indicates a strong association between PLTs and sepsis, with thrombocytopenia commonly observed in affected patients42,43,44.

Recent studies have explored biomarker ratios, including the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, CRP-to-albumin ratio, and PCT-to-albumin ratio45,46,47,48,49,50,51, for their diagnostic and prognostic relevance in sepsis. Our prior research identified CPR as clinically significant in diagnosing sepsis-related conditions among neonates with suspected sepsis52. However, limited data exist regarding the diagnostic value of CPR in distinguishing neonatal LOS (positive blood culture) in NWP. CPR, calculated as the ratio of CRP to PLT count, reflects both inflammatory and coagulation dynamics. This study evaluated the diagnostic efficacy of CPR in differentiating neonatal LOS in NWP. Consistent with earlier findings53, elevated CPR levels were observed in NWS compared to pneumonia cases, and higher CPR values correlated with prolonged hospital stays. Multivariate analysis identified CPR as an independent risk factor for sepsis detection in NWP, while ROC curve analysis demonstrated that CPR surpassed CRP levels and PLT count individually in differentiating NWS from NWP. However, CPR’s diagnostic accuracy remains moderate, necessitating cautious interpretation. CRP values below the threshold do not exclude NWS, and neonates with elevated CPR require further diagnostic evaluation to confirm sepsis.

This study demonstrates that elevated CPR is associated with a heightened risk of NWS, offering potential for improving clinical decision-making and optimizing resource allocation in neonatal care. This study highlights the relevance of CPR as a biomarker for distinguishing between NWS and NWP, suggesting its incorporation into existing clinical workflows to enable earlier and more precise diagnoses. Prioritizing CPR assessment in neonates at risk may strengthen the ability to initiate timely interventions, a critical factor in mitigating severe morbidity and mortality associated with diagnostic delays.

This study has several limitations that require acknowledgment. First, as a single-center retrospective observational analysis, the generalizability of the results may be limited, highlighting the need for confirmation through multicenter studies. Second, the relatively small cohort of newborns diagnosed with LOS suggests that future research involving larger sample sizes is essential to derive more robust and reliable conclusions. Lastly, CPR measurements are restricted to admission values; longitudinal monitoring of CPR levels throughout disease progression could provide valuable insights into its diagnostic relevance for distinguishing sepsis from pneumonia in neonates.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the potential of CPR as a diagnostic marker for distinguishing sepsis from pneumonia in neonates. Results indicate that CPR offers superior diagnostic accuracy compared to CRP or platelet count individually in differentiating NWS from NWP.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- NWP:

-

Neonates with pneumonia

- NWS:

-

Neonates with sepsis

- CPR:

-

C-reactive protein to platelet ratio

- LOS:

-

Late-onset sepsis

- IRFs:

-

Independent risk factors

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- PLTs:

-

Platelets

- SIRS:

-

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- ALT:

-

Aminotransferase

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- CREA:

-

Creatinine

- UREA:

-

Urea nitrogen

- PCT:

-

Procalcitonin

- WBC:

-

White blood cells

- AUC:

-

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

References

Camacho-Gonzalez, A., Spearman, P. W. & Stoll, B. J. Neonatal infectious diseases: Evaluation of neonatal sepsis. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 60, 367–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2012.12.003 (2013).

Korang, S. K. et al. Antibiotic regimens for late-onset neonatal sepsis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 5, CD013836. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013836.pub2 (2021).

Lawn, J. E., Cousens, S., Zupan, J., Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering, T. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why?. Lancet (London, England). 365, 891–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5 (2005).

Liu, L. et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–15: An updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet (London, England) 388, 3027–3035. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31593-8 (2016).

Weiss, S. L. et al. Surviving sepsis campaign international guidelines for the management of septic shock and sepsis-associated organ dysfunction in children. Intensive Care Med. 46, 10–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05878-6 (2020).

Shane, A. L., Sánchez, P. J. & Stoll, B. J. Neonatal sepsis. Lancet (London, England) 390, 1770–1780. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)31002-4 (2017).

Iroh Tam, P. Y. & Bendel, C. M. Diagnostics for neonatal sepsis: Current approaches and future directions. Pediatr. Res. 82, 574–583. https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2017.134 (2017).

Black, S., Kushner, I. & Samols, D. C-reactive protein. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 48487–48490. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.R400025200 (2004).

Sproston, N. R. & Ashworth, J. J. Role of C-reactive protein at sites of inflammation and infection. Front. Immunol. 9, 754. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00754 (2018).

Dhingra, R. et al. C-reactive protein, inflammatory conditions, and cardiovascular disease risk. Am. J. Med. 120, 1054–1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.08.037 (2007).

Smilowitz, N. R. et al. C-reactive protein and clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. Eur. Heart J. 42, 2270–2279. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa1103 (2021).

Stocker, M. et al. C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and white blood count to rule out neonatal early-onset sepsis within 36 hours: A secondary analysis of the neonatal procalcitonin intervention study. Clin. Infect. Diseases 73, e383–e390. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa876 (2021).

Wang, H. E. et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and risk of sepsis. PLoS One 8, e69232. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069232 (2013).

Khan, F. C-reactive protein as a screening biomarker in neonatal sepsis. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 29, 951–953. https://doi.org/10.29271/jcpsp.2019.10.951 (2019).

Shannon, O. The role of platelets in sepsis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 5, 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/rth2.12465 (2021).

Greco, E., Lupia, E., Bosco, O., Vizio, B. & Montrucchio, G. Platelets and multi-organ failure in sepsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18102200 (2017).

Russwurm, S. et al. Platelet and leukocyte activation correlate with the severity of septic organ dysfunction. Shock (Augusta, Ga.) 17, 263–268. https://doi.org/10.1097/00024382-200204000-00004 (2002).

Chen, Y., Zhong, H., Zhao, Y., Luo, X. & Gao, W. Role of platelet biomarkers in inflammatory response. Biomark. Res. 8, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-020-00207-2 (2020).

Guida, J. D., Kunig, A. M., Leef, K. H., McKenzie, S. E. & Paul, D. A. Platelet count and sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: Is there an organism-specific response?. Pediatrics 111, 1411–1415. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.6.1411 (2003).

Guclu, E., Durmaz, Y. & Karabay, O. Effect of severe sepsis on platelet count and their indices. Afr. Health Sci. 13, 333–338. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v13i2.19 (2013).

Claushuis, T. A. et al. Thrombocytopenia is associated with a dysregulated host response in critically ill sepsis patients. Blood 127, 3062–3072. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-11-680744 (2016).

Xiang, C. Zhufutang practical pediatrics (8th edition). Chin. J. Clin. Physicians. 43, 46–48 (2015).

Goldstein, B., Giroir, B. & Randolph, A. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: Definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 6, 2–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.Pcc.0000149131.72248.E6 (2005).

Hughes, G. Youden’s index and the weight of evidence. Methods Inf. Med. 54, 198–199. https://doi.org/10.3414/ME14-04-0003 (2015).

Nissen, M. D. Congenital and neonatal pneumonia. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 8, 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prrv.2007.07.001 (2007).

Boomer, J. S. et al. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA 306, 2594–2605. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1829 (2011).

World Sepsis Day 2017-Preventable Maternal and Neonatal Sepsis a Critical Priority for WHO and Global Sepsis Alliance. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58a7025b8419c215b30b2df3/t/59b1b9d52994caee6bc0eba7/1504819673100/Press_Release_WSD_WSC_English_Letterhead+(PDF).pdf (2017).

Oza, S., Lawn, J. E., Hogan, D. R., Mathers, C. & Cousens, S. N. Neonatal cause-of-death estimates for the early and late neonatal periods for 194 countries: 2000–2013. Bull. World Health Organ. 93, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.14.139790 (2015).

Scheer, C. S. et al. Impact of antibiotic administration on blood culture positivity at the beginning of sepsis: A prospective clinical cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 25, 326–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2018.05.016 (2019).

Lamy, B., Dargère, S., Arendrup, M. C., Parienti, J. J. & Tattevin, P. How to optimize the use of blood cultures for the diagnosis of bloodstream infections? A state-of-the art. Front. Microbiol. 7, 697. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00697 (2016).

Chen, X. H., Yin, Y. J. & Zhang, J. X. Sepsis and immune response. World J. Emerg. Med. 2, 88–92 (2011).

van der Poll, T., Shankar-Hari, M. & Wiersinga, W. J. The immunology of sepsis. Immunity 54, 2450–2464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2021.10.012 (2021).

Du Clos, T. W. Function of C-reactive protein. Ann. Med. 32, 274–278. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853890009011772 (2000).

Stocker, M. et al. C-Reactive protein, procalcitonin, and white blood count to rule out neonatal early-onset sepsis within 36 hours: A secondary analysis of the neonatal procalcitonin intervention study. Clin. Infect. Diseases. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa876 (2020).

Povoa, P. et al. C-reactive protein as an indicator of sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 24, 1052–1056. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001340050715 (1998).

Eschborn, S. & Weitkamp, J. H. Procalcitonin versus C-reactive protein: Review of kinetics and performance for diagnosis of neonatal sepsis. J. Perinatol. 39, 893–903. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-019-0363-4 (2019).

Hofer, N., Zacharias, E., Muller, W. & Resch, B. An update on the use of C-reactive protein in early-onset neonatal sepsis: Current insights and new tasks. Neonatology 102, 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1159/000336629 (2012).

Denorme, F. & Campbell, R. A. Procoagulant platelets: Novel players in thromboinflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 323, C951–C958. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00252.2022 (2022).

Garraud, O. & Cognasse, F. Are platelets cells? And if yes, are they immune cells?. Front. Immunol. 6, 70. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2015.00070 (2015).

Mandel, J., Casari, M., Stepanyan, M., Martyanov, A. & Deppermann, C. Beyond hemostasis: Platelet innate immune interactions and thromboinflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23073868 (2022).

Duerschmied, D., Bode, C. & Ahrens, I. Immune functions of platelets. Thromb. Haemost. 112, 678–691. https://doi.org/10.1160/TH14-02-0146 (2014).

Morrell, C. N., Aggrey, A. A., Chapman, L. M. & Modjeski, K. L. Emerging roles for platelets as immune and inflammatory cells. Blood 123, 2759–2767. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-11-462432 (2014).

Thiery-Antier, N. et al. Is thrombocytopenia an early prognostic marker in septic shock?. Crit. Care Med. 44, 764–772. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001520 (2016).

de Stoppelaar, S. F., van ‘t Veer, C. & van der Poll, T. The role of platelets in sepsis. Thromb. Haemost. 112, 666–677. https://doi.org/10.1160/TH14-02-0126 (2014).

Li, T. et al. Association of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and the presence of neonatal sepsis. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 7650713. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7650713 (2020).

Kriplani, A. et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and lymphocyte-monocyte ratio (LMR) in predicting systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and sepsis after percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PNL). Urolithiasis 50, 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-022-01319-0 (2022).

Russell, C. D. et al. The utility of peripheral blood leucocyte ratios as biomarkers in infectious diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 78, 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2019.02.006 (2019).

Wang, Q. Y., Lu, F. & Li, A. M. (2022) The clinical value of high mobility group box-1 and CRP/Alb ratio in the diagnosis and evaluation of sepsis in children. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 26, 6361–6366. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202209_29662

Wang, X., Jing, M., Li, L. & Xu, Q. The prognostic value of procalcitonin clearance and procalcitonin to albumin ratio in sepsis patients. Clin. Lab. https://doi.org/10.7754/Clin.Lab.2022.220613 (2023).

Li, T. et al. Association of procalcitonin to albumin ratio with the presence and severity of sepsis in neonates. J. Inflamm. Res. 15, 2313–2321. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S358067 (2022).

Li, T. et al. Predictive value of C-reactive protein-to-albumin ratio for neonatal sepsis. J. Inflamm. Res. 14, 3207–3215. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S321074 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Clinical value of C-reactive protein/platelet ratio in neonatal sepsis: A cross-sectional study. J. Inflamm. Res. 14, 5123–5129. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S334642 (2021).

Aggarwal, S., Sangle, A. L., Siddiqui, M. S., Haseeb, M. & Engade, M. B. An observational study on C-reactive protein to platelet ratio in neonatal sepsis. Cureus 16, e62230. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.62230 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Bullet Edits Limited for their editorial assistance and manuscript revision services.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82200097), the Key Research, Development, and Promotion Projects of Henan Province (252102310054 and 232102310122), and the Medical Science and Technology Project of Henan Province (LHGJ20220774).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaojuan Li and Tiewei Li were responsible for project design and administration, manuscript writing, and funding acquisition. Fatao Lin, Ci Li, and Qingdao Bai contributed to data collection and statistical analysis. Tiewei Li, Hui Fu and Zhipeng Jin provided overall guidance and managed the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The investigation was executed per the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was approved by the Hospital Ethics Review Board of Henan Children’s Hospital (No. 2024-009). The research ensures that participant identities and associated information remain anonymous and protected. Informed consent was waived due to its retrospective nature along with the institution name by which it has been waived.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Li, T., Fu, H. et al. C-reactive protein to platelet ratio as an early biomarker in differentiating neonatal late-onset sepsis in neonates with pneumonia. Sci Rep 15, 10760 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94845-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94845-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Staged identification of CAP in fever patients across epidemic environments: modeling & validation

Scientific Reports (2025)