Abstract

In this study, Large Eddy Simulation (LES) has been employed to examine the influence of the Froude number (Fr) on the linearly stratified wake and internal waves behind a sphere at a subcritical Reynolds number of Re = 3700. Six distinct sets of models with varying Fr (Fr = 0.05, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, ∞) have been chosen to establish density linear stratification through the use of a User Defined Function (UDF). The analysis focuses on the impact of stratification on wake characteristics, velocity distribution, and the structure of internal waves within stratified flow. It is evident that density stratification plays a pivotal role in shaping wake structure. Notably, in stratified flows, wakes exhibit unique characteristics including the generation of internal waves, suppression of vertical velocity, and the emergence of oscillating wake patterns. The study reveals that a decrease in the Froude number leads to heightened vertical suppression of the wake and increased anisotropy of the velocity distribution. Furthermore, as the Froude number ascends from 0.05 to 2, the wake undergoes a transition from quasi-two-dimensional vortex shedding to three-dimensional turbulence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The study of the flow past a sphere has attracted widespread attention due to the intricate and fascinating characteristics of turbulent wake, unsteady vortex shedding, and the transition from laminar to turbulent flow. Kim and Durbin1, as well as Sakamoto and Haniu2, delved into the wake flow behind a sphere using flow visualization techniques to gain a deeper understanding of the complex phenomena involved. Their investigations encompassed a wide range of Reynolds numbers, shedding light on the significant impact of the Reynolds number (Re) on the wake flow behind the sphere. Kim and Durbin1 specifically focused on the flow past a sphere within a Reynolds number range of 500 to 60,000, uncovering two distinct unstable frequency modes within this range: a low-frequency mode attributed to large-scale vortex shedding and a high-frequency mode arising from the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability in the separating shear layer. Meanwhile, Sakamoto and Haniu2 conducted a comprehensive classification of the flow within the range 300 < Re < 370,000, identifying four distinct regions based on the vortex shedding modes. Their detailed observations revealed that within the range 300 < Re < 800, hairpin vortices begin to shed periodically with regular intensity and frequency, giving rise to laminar vortices. As the Reynolds number increases to 800 < Re < 370,000, the hairpin vortices undergo a transition from laminar to turbulent vortices, characterized by alternating fluctuations.

The development and widespread use of computational fluid dynamics have significantly advanced the analysis of subcritical turbulent wake flows through numerical simulation methods. Researchers such as Siedl et al.3, Tomboulides and Orszag4, Constantinescu5, Yun6, and Rodriguez7 have employed direct numerical simulation (DNS) and large eddy simulation (LES) to meticulously study wake flow, vortex shedding, and drag characteristics on a sphere at subcritical Reynolds numbers. Constantinescu5 specifically utilized LES to explore the flow around spheres at both subcritical and supercritical Reynolds numbers, identifying a strong correlation between the Reynolds number and the orientation and frequency of vortex shedding. Furthermore, Yun6 conducted LES to delve into the shear layer and wake instability, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of these complex phenomena.

The studies mentioned are based on simulations of homogeneous flow, which do not fully capture the complexities of real bodies of water such as the ocean8, rivers, and atmospheric conditions9. These natural environments are influenced by various factors including temperature, pressure, and salinity, leading to the development of density stratification in the vertical direction. In stratified flow, the formation of vortical structures and wake flow characteristics is not only dependent on the Reynolds number but is also impacted by the Froude number. Early studies on stratified flow by Lin10, Chomaz11, and Boyer et al.12 utilized towed spheres or circular cylinders to explore the near wake flow patterns across a wide range of Froude (Fr) and Reynolds numbers. These studies concluded that both Fr and Re play significant roles in governing wake characteristics in stratified flow.

In recent research, numerical simulations have been utilized to explore the impact of stratified turbulent wake. Various methods such as DNS, LES, and others have been employed by researchers13,14,15,16 to investigate how stratification affects the wake structure. They discovered that stratification changes the far wake structure and extends the wake lifetime at Froude numbers greater than the critical Fr. Specifically, Gourlay13, Pasquetti14, Diamessis15, Ortiz-Tarin16, and Pal17 conducted simulations to study submerged bodies at subcritical Reynolds numbers for different Froude numbers. Pal17 particularly advocated for further investigation of the vortical structure in stratified flow at high Re and low Fr. Chongsiripinyo18 and Cao19 used DNS and IDDES (Improved Delayed Detached Eddy Simulation) at Re = 3700 to examine the impact of stratification on the wake, finding that it influences the vortical structure behind the sphere, leading to changes in the shape of the vortex tube and anisotropic distribution of vorticity.

It is essential to recognize that only a few studies have examined the flow characteristics in strongly stratified wakes at moderate to high Reynolds numbers. To enhance our understanding of the near-wake properties of strongly stratified flow around a sphere at a moderate Reynolds number of Re = 3700, this study uses Large Eddy Simulation to numerically model the wake. The study aims to comprehensively explain the effects of stratification on the wake structure, covering the velocity field behind the sphere, vortical structures, internal wave, and wake instability.

Numerical methods

Computational domains and grids

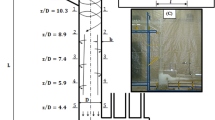

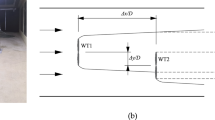

A cubic computational domain has been established with dimensions of length L = 80D, width W = 20D, and height H = 20D (D is the diameter of the sphere), as illustrated in Fig. 1. A Cartesian coordinate system is employed, with the origin positioned at the center of the sphere. In this system, the x, y, and z coordinates correspond to the horizontal, lateral, and vertical directions. The sphere is strategically located 20D from the inlet, 10D from the upper and lower walls, and 10D from each side wall. Additionally, the mesh configuration of the computational domain, shown in Fig. 2, features refined mesh elements in proximity to the sphere to enhance computational accuracy.

For validation purposes, a grid sensitivity analysis was performed using five grid resolutions, ranging from coarse (1.2 million cells) to fine (2.5 million cells). As shown in Fig. 3, the Strouhal number (St) obtained from simulations of the flow around a sphere in non-stratified conditions demonstrated negligible sensitivity to further refinement beyond 2.2 million cells. Therefore, a grid resolution of 2.2 million was selected to balance accuracy and computational efficiency.

Simulation settings

The Large Eddy Simulation20,21,22 is used with the Coupled algorithm to solve the discretized equations. The dynamic Smagorinsky-Lilly23 model was employed, which dynamically evaluates the Smagorinsky coefficient based on flow characteristics. The inlet is designated as a velocity inlet with a constant fluid velocity representing the sphere’s uniform motion relative to the surrounding fluid. The outlet is configured as a pressure outlet. The side walls are defined as symmetry planes, while the upper and lower walls are sliding walls moving at the inlet velocity. The corresponding temperatures are specified at the upper and lower walls. The unstratified flow over a sphere at a Reynolds number of Re = 3700 is verified against the previous experimental and numerical data1,2,6,7,24 (see Table 1), the time-averaged drag coefficient \(\overline {{{{\text{C}}_d}}}\), the base pressure coefficient \(\overline {{{{\text{C}}_{pb}}}}\), the Strouhal number \(St\), and the separation angle \(\overline {{{\Phi _s}}} (deg)\)shows good agreements among the present and previous results.

Six sets of simulations for sphere wakes with different Fr values (0.05, 0.2, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and \(\infty\)) have been selected for comparative study.

Results and discussion

Instantaneous flow fields

Figures 4(a) and (b) depict the near wake structures of the flowfields behind a sphere at a Froude number of Fr = 0.05. In the horizontal center planes (Fig. 4a), large-scale vortex shedding is evident. In the vertical center planes, the wake structure reveals a three-layer distribution: the upper boundary layer, the lower boundary layer, and the central layer of quasi-two-dimensional flow, as shown in Fig. 4(b). Within the central layer, the vertical flow velocity is nearly zero, and the flow field exhibits quasi-two-dimensional flow. This behavior is primarily attributed to buoyancy, which dominates inertial forces in flowfields at lower Froude numbers. Under the influence of buoyancy, the fluid’s inertial force is unable to overcome the buoyancy exerted by the surrounding fluid, preventing it from ascending over the sphere from a vertical direction. Consequently, the liquid can only flow horizontally around the two sides of the sphere, forming the central layer.

As the Froude number Fr increases from 0.05 to 0.25, a significant change in the wake structure is observed, as depicted in Fig. 4(c) and (d). The thickness of the central layer behind the sphere decreases, and simultaneously, oscillations occur in the upper and lower boundaries behind the sphere, resulting in lee waves. Unlike the behavior at Fr = 0.05, some fluids can ascend over the sphere in the vertical direction at Fr = 0.25. Subsequent to crossing the sphere, the fluid is influenced by gravity, resulting in oscillatory wakes that disrupt the initially stable density stratification and trigger the generation of internal waves.

In order to delve deeper into the characteristics of the vortical structure behind the sphere, we employed the Q criterion to identify the vortex formations in the wake behind the sphere, as illustrated in Figs. 5 and 6. Figure 5 reveals that at Fr = 0.05, the vortex sheet displays a three-layer structure, shedding periodically along the flow direction. The upper and lower boundary layers detach in an inclined manner, while the central layer detaches horizontally. The interconnected three-layer vortex structures form a V-shaped11 vortical pattern due to the vertical coherence of the flow. Additionally, fine-scale structures near the sphere were identified, indicated by the red dashed box in Fig. 5(b). These structures are believed to be caused by “turbulence regeneration” due to an increase in horizontal shear stress25. At Fr = 0.05, minimal fluid passing over the sphere resulted in less disturbance of density stratification in the vertical direction, and consequently, no significant internal waves were observed.

As depicted in Fig. 6, the vortex structures behind the sphere did not exhibit significant large-scale vortex shedding at Fr = 0.25. Vortex structures within the hump of the internal wave were observed in Fig. 6(a), indicated by the black dashed box. Additionally, slender vortices on both sides of the sphere in Fig. 6(a) are related to the shear layers covering the recirculation zone behind the sphere. Furthermore, Fig. 6(b) illustrates the generation and excitation of internal waves due to the wake oscillation formed by the fluid crossing the sphere, as shown by the black dashed line.

At a Froude number of Fr = 0.5 (as depicted in Fig. 7a–b), the wake behind the sphere is characterized by the prevalence of saturated Lee waves11. At this juncture, the amplitude of the Lee waves reaches its peak, giving rise to a stable and symmetrical wake structure under the influence of the Lee waves. This phenomenon is accompanied by an increased flow of fluid over the sphere from a vertical direction, leading to the disappearance of the central layer. In comparison to Fr = 0.25 (Fig. 4d), the amplitude and the wavelength of the internal wave are heightened at Fr = 0.5. In the horizontal center plane, the fluid traverses horizontally through both sides of the sphere and converges at a dimensionless streamwise location of X/D = 2.5, creating a hollow region at \(1 \leqslant X/D \leqslant 2.5\). Notably, unlike the wake structures formed at Fr = 0.05 and 0.25, no shedding vortices were observed at Fr = 0.5. According to Chomaz11, saturated Lee waves are believed to suppress the generation of vortex shedding.

As the Froude number increases to Fr = 1 (as illustrated in Fig. 7c–d), the wake enters a transitional phase from a saturated Lee waves-dominated regime to a turbulent wake regime unaffected by density stratification. During this transition, the influence of buoyancy gradually diminishes, while the impact of inertial force intensifies. The wake continues to oscillate in the vertical direction (Fig. 7d), and a recirculation zone emerges behind the sphere in comparison to Fr = 0.5.

At Fr = 2, the wake behind the sphere shows only a slight impact from stratification effects, with inertial forces prevailing over buoyancy. As a result, the turbulent structure in the wake becomes more pronounced, resembling an unstratified state similar to the near wake structure observed at Fr=∞. This phenomenon is visually represented in Fig. 8, wherein a discernible recirculation zone forms behind the sphere, encircled by asymmetric vortex structures. Despite the minimal impact of stratification on the wake behind the sphere, it still contributes to the generation and propagation of internal waves. Notably, researchers such as Chomaz25, Hopfinger27, Lin28, and Robey29 have documented through towed-sphere experiments that internal waves generated at Fr = 2 are predominantly influenced by the wake effect.

Figure 9 illustrates the wake structure in a uniform flow at Fr=∞. A recirculation zone is observed to develop behind the sphere, resulting in an asymmetric vortex structure. Vortex shedding occurs at the streamwise position of X/D = 1.5. For improved insight into the changes in the wake structure, Q-criterion visualization was conducted at Fr=∞, as depicted in Fig. 10. Vortex rings are generated on the sphere’s surface, subsequently expanding and, influenced by the shear layer, transforming into detached hairpin vortices.

Time-averaged flow fields

The time-averaged flow fields in the horizontal and vertical center planes are depicted in Figs. 11 and 12, respectively. Comparison of Fig. 11(a) and Fig. 12(a) reveals that at Fr=∞, the wake flow field exhibits isotropy, leading to nearly identical wake patterns in both the vertical and horizontal planes. As the Froude number (Fr) decreases to Fr = 2, the wake is progressively influenced by the fluid stratification effect. In the vertical direction (Fig. 12b), the vertical height of the recirculation zone diminishes gradually, while the wake width in the horizontal direction marginally increases in comparison to Fr=∞, owing to density stratification. The wake distribution in both horizontal and vertical planes displays anisotropy due to the density stratification, with the vertical flow being suppressed and some fluids tending to flow around the sphere from the horizontal direction. Consequently, the size of the horizontal recirculation zone increases. At Fr = 1, the impact of stratification intensifies, further decreasing the vertical size of the recirculation zone. The time-averaged flow field at Fr = 1 in the vertical direction is characterized by vertically oscillating Lee wave structures.

At Fr = 0.5, the time-averaged wake structure resembles the transient wake structure (as shown in Fig. 7), with saturated Lee waves dominating the wake structure, resulting in a stable wake. Comparing with the scale of Lee waves formed at Fr = 1, it is observed that at Fr = 0.5, the wavelength of Lee waves decreases and the amplitude increases.

At Fr = 0.05, owing to the significant effect of stratification, the size and amplitude of the Lee wave are significantly reduced, with only weak Lee waves observed within a 2D range behind the sphere. Simultaneously, the time-averaged flow fields of Fig. 11(e) and (f) reveal conspicuous acceleration zones on both sides of the sphere (indicated by black dashed boxes), where the flow exhibits significantly higher time-averaged velocity than the background fluid. This suggests that at small Froude numbers, the flow is more inclined towards horizontal flow around the sphere.

Vortical structures

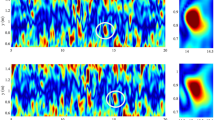

Figures 13 and 14 illustrate the contours of vorticity in the horizontal and vertical central planes at varying Fr numbers. In Figs. 13 (a) and 14 (a), it is evident that at Fr=∞, the vortex rings are formed behind the sphere and subsequently shed into the wake in a spiral mode. Kim and Durbin1 noted that in uniform flow, the wake instability is highly related to the Reynolds number. When the Reynolds number exceeds 800, the wake experiences simultaneous effects from Kelvin-Helmholtz instability and helical instability. Chomaz11 conducted an analysis of the spatiotemporal characteristics of the uniform flow wake in a Reynolds range of \(150 \leqslant Re \leqslant 30,000\) using flow visualization techniques, further affirming Kim and Durbin’s1 findings by identifying three distinct unstable modes within this Reynolds number range. At the present Reynolds number Re = 3700, the wake is subject to both Kelvin-Helmholtz instability and spiral instability. At Fr = 2, the vortex structure in the wake mirrors that of Fr=∞, which is shed in a spiral mode after its formation, as depicted in Figs. 13 (b) and 14 (b).

At Fr = 1, the wake undergoes a transition from a saturated Lee wave regime to a 3D turbulent wake. This transition is characterized by the presence of turbulent structures in the wake and the disappearance of spiral shedding. Additionally, the decrease in the Froude number results in an enhanced anisotropy of the vortex structure behind the sphere, accompanied by the generation of weak waves in the vertical direction due to the Lee wave (Fig. 14c).

As the Froude number decreases to Fr = 0.5, it is observed that the shedding of vortex structures is suppressed by saturated Lee waves, leading to the distribution of slender shear layers horizontally on both sides of the sphere (Fig. 12d). Under the influence of buoyancy, the separated shear layer contracts towards the center in the vertical direction, followed by the formation of steady waves. Lee waves are prominently visible in the contour (Fig. 14d).

Further scrutiny at Fr = 0.25 reveals that the wake tends to flow horizontally due to the suppression by stratification in the vertical direction. This is accompanied by an increase in the streamwise size of the recirculation zone (Fig. 13e). In the vertical direction (Fig. 14e), the wake is observed to be divided into three layers, with distinct Lee waves at \(0.5 \leqslant X/D \leqslant 3\).

As the Froude number decreases to 0.05, the wake undergoes significant changes. The sphere becomes surrounded by fine-scale turbulent structures at \(0.5 \leqslant X/D \leqslant 1\), and weak Lee wave traces can be observed in Fig. 14(f). At \(X/D>1\), the vortex structure behind the sphere transforms into a two-dimensional vortex that alternately sheds into the wake. In the vertical direction, it is suppressed by the stratification effect and still maintains a three-layer structure. The separation of the upper and lower boundary layers causes the shedding speed to increase, pulling the vortex structure of the central layer and forming a “V” shaped structure in the vertical central plane (Fig. 14f).

Velocity fluctuation

In Fig. 15, the diagram illustrates the distribution of lateral and vertical fluctuating velocities in the direction of flow. At Fr = 0.05, depicted in Fig. 15(a), the amplitude of lateral fluctuating velocity \({v^\prime }/{U_\infty }\) is notably larger than that at other Fr values, gradually diminishing along the flow direction. With the increase of the Froude number, the amplitude of the velocity fluctuation decreases rapidly. At Fr = 0.05 and 0.25, the periodic shedding of the vortices induces significant lateral fluctuations. At Fr = 0.5, the wake is dominated by Lee waves, resulting in near-zero lateral fluctuation. As Fr further increases to 1, 2, and ∞, the lateral fluctuation gradually recovers due to the transition of the flow field to turbulent flow.

Figure 15(b) reveals the streamwise distribution of the vertical fluctuating velocity \({w^\prime }/{U_\infty }\). The amplitude of vertical fluctuating velocity at Fr = ∞ surpasses that of other Fr values and resembles the amplitude of lateral fluctuating velocity. The distribution of the vertical fluctuating velocity at other Fr values is considerably smaller, especially at Fr values of 0.05, 0.25, and 0.5, indicating the suppression of vertical motion by stratification.

Conclusions

In this study, an in-depth numerical investigation into the wake characteristics of the stratified flow past a sphere has been undertaken, analyzing six distinct sets of internal Froude numbers (Fr = 0.05, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and ∞) at a moderate Reynolds number of Re = 3700. The study provides a comparative analysis of the impact of Fr numbers on the characteristics of the wake flowfield.

The density stratification plays a crucial role in shaping the characteristics of wake structure. As the Froude number (Fr) increases from 0.05 to 2, the wake undergoes a transition from quasi-two-dimensional vortex shedding to three-dimensional turbulence. In stratified flows, the wakes display unique features such as the generation of internal waves, suppression of vertical velocity, and the emergence of oscillating wake patterns. These distinctive characteristics are primarily influenced by the balance between inertial and buoyancy forces. When buoyancy dominates (observed at Fr = 0.05, 0.25), the vertical movement of the fluid is suppressed, resulting in quasi-two-dimensional flow. As the influence of inertial force grows (notably at Fr = 0.25, 0.5, 1), the vertical fluid overflow intensifies, leading to the development of oscillating wakes and the excitation of internal waves. When inertial force becomes dominant, the wake becomes less affected by stratification and more susceptible to Reynolds effects. In the context of this study, with Re = 3700, the wake structure transitions to a hairpin vortex helix shedding pattern, resembling that of unstratified wakes at Fr = 2. The findings of this study can enhance our understanding of wakes around underwater vehicles such as submarines. This research supports the development of flow control technologies aimed at reducing drag and minimizing wake visibility.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request. If someone wants to request the data from this study, they can contact corresponding author (Liuliu Shi).

References

Kim, H. J. & Durbin, P. A Observations of the frequencies in a sphere wake and of drag increase by acoustic excitation. Phys. Fluids, 31: 3260–3265 (1998) .

Sakamoto, H. & Haniu, H. A study on vortex shedding from spheres in a uniform flow. ASME J. Fluids Eng. 112 (4), 386–392 (1990).

Seidl, V., Muzaferija, S. & Perić M. Parallel DNS with local grid refinement. Flow Turbul. Combust. 59, 379–394 (1997).

Tomboulides, A. G. et al. Direct and Large-Eddy Simulation of the Flow Past a Sphere. Engineering Turbulence Modelling and Experiments, Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Engineering Turbulence Modelling and Measurements, Pages 273–282. (1993).

Constantinescu, G. & Squires, K. Numerical investigations of flow over a sphere in the subcritical and supercritical regimes. Phys. Fluids. 16 (5), 1449–1466 (2004).

Yun, G. Kim, D. & Choi, H. Vortical structures behind a sphere at subcritical Reynolds numbers. Phys. Fluids, 18:015102 (2006).

Rodriguez, I., Borelli, Y., Lehmkuhl, O. & Perez Sefarra, C. D. & Olliva, A. Direct numerical simulation of the flow over a sphere at re = 3700. J. Fluid Mech., 679:263–287 (2011).

Tomczak, M. Island wakes in deep and shallow water. J. Phys. Res. 93 (C5), 5153–5154 (1988).

Rotunno, R., Grubisic, V. & Smolarkiewicz, P. K. Vorticity and potential vorticity in mountain wakes. Atmospheric Sci. Lett. 56 (16), 2796–2810 (1999).

Lin, Q., Lindberg, W. R., Boyer, D. L., Fernando, H. & J S. Stratified flow past a sphere. J. Fluid Mech. 240, 315–354 (1992).

Chomaz, J. M., Bonneton, P. & Hopfinger, E. J. The structure of the near wake of a sphere moving horizontally in a stratified fluid. J. Fluid Mech. 254, 1–21 (1993).

Boyer, D. L. et al. (1989)Linearly Stratified Flow Past a Horizontal Circular Cylinder. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 328:1601. (1934)–1990.

Gourlay, M. J., Arendt, S. C. & Fritts D. C. & Werne, J. Numerical modeling of initially turbulent wakes with net momentum. Phys. Fluids, 13:3783–3802 (2001).

Pasquetti, R. Temporal/spatial simulation of the stratified Far wake of a sphere. Comput. Fluids. 40 (1), 179–187 (2011).

Diamessis, P. J., Spedding, G. R. & Domaradzki, J. A. Similarity scaling and vorticity structure in high Reynolds number stably stratified turbulent wakes. J. Fluid Mech. 671, 52–95 (2011).

Ortiz Tarin, Jose, L. & Chongsiripinyo, K. C. & Sarkar S(2019)Stratified flow past a prolate spheroid. Phys. Rev. Fluids, 4 (9): 094803 .

Pal, A., Sarkar, Sutanu, Posa, A. & Balaras, E. Regeneration of turbulent fluctuations in low-froude-number flow over a sphere at a Reynolds number of 3700. (2016). Journal of Fluid Mechanics,804.

Chongsiripinyo, K., Pal, A. & Sarkar, S. On the vortex dynamics of flow past a sphere at re = 3700 in a uniformly stratified fluid. Phys. Fluids. 29 (2), 020704 (2017).

Cao, L. S. et al. Vortical structures and wakes of a sphere in homogeneous and density stratified fluid. Jounal Hydrodynamics. 33 (2), 207–215 (2021).

Kumari, R., Das, B. S. & Mohanty, M. P. Hydrodynamic performance of raceway pond using k-ω and LES turbulence models. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy. 16 (6), 063101 (2024).

Kumar, N., Sandilya, S. S. & Das, B. S. Velocity and shear distribution in converging compound channel using large eddy simulation (LES) turbulence model. Hydraulics Fluid Mech. 1, 321–333 (2025).

Inoue, T., Hirotsugu, Y., Kashiwada, J. & Nihei, Y. Interaction between horseshoe vortex structure and sediment transport around a river rectangular pier using a solid-liquid two-phase turbulent LES model. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 186, 105153 (2025).

Shi, L. L., Yang, G. E. & Yao, S. C. Large eddy simulation of flow past a square cylinder with rounded leading corners: A comparison of 2D and 3D approaches. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 32 (6), 2671–2680 (2018).

Schlichting, H. Boundary layer Theory(Seventh Edition. J. Fluid Mech. 102 (1), 125 (1980).

Spedding, G. R. Wake signature Detection[J]. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 46, 273–302 (2014).

Chomaz, J. et al. Gravity wave patterns in the wake of a sphere in a stratified fluid. In Turbulence and Coherent Structures, 2: 489–503. (1991).

Hopfinger, E. J., Flor, J. B., Chomaz, J. M. & Bonneton, P. Internal waves generated by a moving sphere and its wake in a stratified fluid[J]. Exp. Fluids. 11, 255–261 (1991).

Lin, Q., Boyer, D. L. & Fernando, H. J. S. Internal waves generated by the turbulent wake of a sphere. Exp. Fluids. 15, 147–154 (1993).

Robey, H. F. The generation of internal waves by a towed sphere and its wake in a thermocline. Phys. Fluids. 9 (11), 3353–3367 (1997).

Funding

This research is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12172227);

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Tianci Xia, Na Wei and Liuliu Shi. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Na Wei and Liuliu Shi and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, T., Wei, N. & Shi, L. Large eddy simulation on the wake characteristics of linearly stratified flow past a sphere. Sci Rep 15, 9970 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94870-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94870-w