Abstract

Zeugodacus cucurbitae (Coquillett) flies significantly impact vegetable production in many tropical regions. This study aimed to identify physiologically and behaviorally relevant volatiles from host plants that could potentially be used for future monitoring and control of female Z. cucurbitae flies. Volatile organic compounds were collected from flower, immature fruit, and mature fruit stages of Cucumis sativus L., Cucurbita pepo L., and Cucurbita mixta L. in field conditions, and were analyzed using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC–MS). A total of 81 compounds were identified from across the three species and their phenological stages. Volatilome diversity was higher within phenological stages of each species than between species. Electrophysiological responses of sexually mature Z. cucurbitae females to host volatiles were recorded using gas chromatography coupled electroantennogram detection (GC–EAD). Active compounds were then formulated into blends for behavioral assays conducted in a six-choice olfactometer. Synthetic blends based on physiologically active compounds from flower and immature fruit headspace attracted more females than blends derived from mature fruit and the paraffin oil control (P < 0.001). Some of the physiologically active compounds were found to be behaviorally redundant. The performance of these blends needs to be assessed under field conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The melon fly, Zeugodacus cucurbitae (Coquillett), is a serious pest of fruits and vegetables worldwide1. It is native to Asia and widely distributed in tropical, and subtropical regions2,3,4. While it shows a strong preference for plant species in the Cucurbitaceae family3, Z. cucurbitae has been recorded on 136 plant species across 30 families, with the highest infestation rates observed in Cucurbitaceae, followed by Solanaceae5.

Female melon flies lay their eggs in young fruits, flowers, and stems of host plants. Besides direct damage caused by larval feeding1,6, indirect damage results from pathogens that infest fruits through oviposition punctures and feeding galleries created by the larvae, ultimately reducing yield. Infestations are particularly severe in cucurbit fields, where unmanaged outbreaks can lead to yield losses of up to 100%1,3,7.

Growers commonly use cover sprays against fruit flies during the fruit’s susceptible stage8. However, synthetic insecticides pose significant risks to human health and the environment, highlighting the urgent need for sustainable alternatives9,10. In response, Integrated pest management (IPM) is a strategy through which the use of insecticides can be reduced. This requires careful monitoring of the pests and use of sustainable alternatives when needed. IPM has been established in selected areas, using a range of tools to target various developmental stages of tephritid flies worldwide11,12,13,14,15. Among the tools deployed in IPM of tephritid fruit flies are semiochemicals, which manipulate the behavior of insect pests16. Semiochemicals play a crucial role in IPM systems for many tephritid pests, often including male attractants used for male annihilation17, and food-based attractants that show a female-biased response18. Food-based attractants, such as fermenting sugars, hydrolyzed proteins, and yeast, tend to broadly attract non-target insects, have a limited field life, and can be challenging to handle18,19. Additionally, gravid Z. cucurbitae females that feed on natural protein sources may bypass borders treated with proteinaceous bait and infest cucurbit fields20. This creates a clear need for the development of specific gravid female attractants, which could be deployed in individual orchards or, particularly in smaller fields, as part of area-wide applications in an integrated manner.

Female tephritid fruit flies rely on host plant volatiles for host location and oviposition21. The preference of females for odors emanating from food sources versus host plants is influenced by their age and physiological state20,22,23,24,25. As female flies undergo ovarian development and mating, their search focus shifts from food to host plants. Developing lures based on volatiles from host plants that specifically attract gravid females could provide an effective strategy to reduce infestation.

Research on fruit flies with narrow host ranges, such as the apple maggot fly, Rhagoletis pomenella (Walsh)26 and the cucumber fly, Bactrocera cucumis (French), has led to the successful development of host-based female lures27. Similar efforts have been made to develop host volatile-based female lure for Z. cucurbitae. Since Z. cucurbitae females are attracted to cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.)20,28, physiologically and behaviorally active compounds have been identified from sources including: pureed cucumbers (Sidurhurst and Jang,19), three-month old cucumber and tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum cultivar “cal- J”, Njuguna et al.29, and mature fruits of ridge gourd (Luffa acutangula L. cv. Mallika, Shivaramu et al.30. These studies, however, primarily focused on mature fruits as the source of host volatiles. Melon flies, in contrast, lay eggs on flowers and young fruits of cucurbit plants6. To address this, the present study collected and analysed headspace volatiles emitted by cucurbit host plants at different phenological stages, highlighting similarities and variations. Moreover, this study compared physiologically and behaviorally relevant compounds from intact flowers, immature and mature fruits of cucurbitaceous plants. The attractiveness of volatile blends from flowers and fruits, differing in composition and component ratios, was tested using a six-choice olfactometer.

Results

Organic volatile compounds of cucurbitaceous plants at different developmental stages

A total of 81 compounds were identified across the flowering, immature, and mature stages of C. sativus, C. pepo and C. mixta. At the species level, C. sativus, C. pepo, and C. mixta shared 64.19%, 62.96%, and 51.85% of the total volatiles, respectively (Fig. 1). Among these, 22.22%, 15.51%, and 12.34% were unique to C. sativus, C. pepo, and C. mixta respectively. Immature fruits contributed the largest proportion of headspace volatiles (60.49%), followed by flowers (53.08%) and mature fruits (46.91%). Overall, 32.5% of the headspace volatiles were shared by all three cucurbitaceous species (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1).

From left to right, the heatmap shows (1) Name of the compounds, (2) chemical classes of the compounds, and (3) amount of the compounds in headspaces at different phenological stages (flower, immature fruit, and mature fruit) of C. mixta, C. pepo and C. sativus respectively. Volatiles are arranged in descending order based on sharedness. The relative abundance (surface area of GCMS peak) of the compounds represented by a gradient from light blue (lowest) to red (highest). Cas numbers of compounds shown in red text were confirmed via synthetic injection.

Decanal, 1H-indole, nona-2,6-dien-1-ol and (E)-non-2-enal were the most abundant compounds in the flower headspace. In contrast, benzyl alcohol, linalool, and benzaldehyde were abundant in the headspace of both flowers and immature fruits. The amount of these compounds in the headspace decreased from the flower to the immature fruit stage. Compounds such as 2-cyclopentylcyclopentan-1-one, 1-(4-ethylphenyl) ethenone, 3-ethylbenzaldehyde and cyclopentanone were abundant across all growth stages (Fig. 1). Overall, the volatilome of C. sativus, C. pepo, and C. mixta exhibited more diversity within the developmental stages than between species (Fig. 2).

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis of C. sativus, C. pepo and C. mixta headspaces at different developmental stages (flower, immature, and mature). The diversity within the volatilomes of different phenological stages was relatively higher than the diversity among species; the stress value for the analysis was 0.081.

Chemical class of cucurbitaceous plants

The flower headspace of both C. sativus and C. pepo was quantitatively dominated by ketones, followed by terpenoids, whereas C. mixta was dominated by terpenoids, followed by aldehydes. In all three species, the headspace of immature and mature fruits was dominated by ketones (Fig. 3).

Chemical class of headspace volatiles of three cucurbitaceous plants at different phenological stages. The graph shows that ketones are the dominant chemical class in the sampled cucurbit plants headspace across all developmental stages. The numbers at the top of each bar indicate the number of compounds in each chemical class. Carboxylic acid, amine, amide and unknown chemical classes are grouped under the " others " category.

Physiologically active compounds

Fourteen GC-EAD active compounds were tentatively identified, of which 10 were confirmed with synthetic standards. Decanal, benzaldehyde, linalool, benzyl alcohol, (E)-non-2-enal, 1,4-dimethoxybenzene, 4-ethylbenzaldehyde, nona-2,6-dien-1-ol, nonanal and propanoic acid were confirmed with synthetics (Figs. 4, 5, and Supplementary Fig. S1-6). Across developmental stages, flowers had the highest number of EAD active compounds (9/10), while immature fruits had six. Five EAD active compounds of immature fruits were also present in the flower headspace, except for 1,4-dimethoxybenzene. Fifty % of the antenna-active compounds were shared by all three cucurbit species. The antenna-active compounds in the headspace of flowers and immature fruits were more similar to each other than to those found in mature fruits (Figs. 5, 6). Regression analysis showed no correlation between the amount of a given volatile compound and the strength of the EAD response (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Representative GC-EAD traces of Z. cucurbitae females in response to C. pepo flower headspace volatiles. The top trace represents the FID chromatogram, while the three lower traces show antennal responses. Gray vertical lines connect antennal responses to their corresponding FID peaks. The time base was 2.00 min, scale: FID = 0.5 mV, EAD = 2 mV. RT refers to the retention time of the compounds.

Z. cucurbitae antennal sensitivity to headspace volatiles of C. mixta, C. pepo, and C. sativus at flowering, immature, and mature fruit stages. The heatmap shows the normalized strength of antennal responses, calculated using the overall antennal response to each plant species and developmental stage (flower, immature fruit, and mature fruit) as the denominator. Compounds are arranged in descending order based on their sharedness and the strength of the antennal response. Compounds labelled in red text were confirmed with synthetic standards.

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis of Z. cucurbitae antenna-active compounds to headspace volatiles from C. sativus, C. pepo and C. mixta at different developmental stages (flower, immature fruits, and mature fruits). Responses to flower and immature fruit stages are more similar to each other (closer in ordination space) compared to those from the mature fruit stage; the stress value for the analysis was 0.079.

Flower and immature fruit volatiles attract females

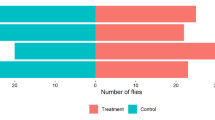

In six-choice assays, both the flower blend (FB) and immature fruit blend (IFB) were more attractive than the mature fruit blend (MFB) and the control (P < 0.001). The highest mean fly catch was recorded for FB (2.29) and IFB (2.14), with no significant difference between them (Fig. 7).

Behavioral preference of sexually mature Z. cucurbitae females for blends of antenna-active compounds in ratios corresponding to each phenological stage of cucurbit hosts. Three paraffin oil controls were placed in between each treatment. The box plots display the median, interquartile ranges, and outliers for fly catches across the different blends and the control. The experiment included 14 replicates, each with 30 sexually mature female flies. Different letters indicate significant differences between means at p < 0.05 means-Kramer, followed by Tukey post hoc tests.

Fly catch comparison among different blends

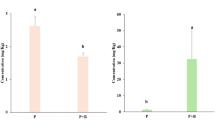

The All_active, Tephri_active, and Zeugo_active blends attracted significantly higher number of flies than the controls (P < 0.001). Moreover, there was no significant difference in mean fly catch among Zeugo_active, Tephri_active and All_active blends. The highest mean fly catch was recorded from the All_active blend (3.27). However, it was not significantly different from Zeugo_active and Tephri_active blends (Fig. 8).

Behavioral preference of sexually mature Z. cucurbitae females to All_active, Tephri_active and Zeugo_active blends. Three paraffin oil controls were placed between each treatment. Box plots show the median, interquartile ranges, and outliers of fly catches for the different blends and control. Number of replicates = 11, with 30 sexually mature female flies per replicate. Different letters indicate significant differences between means at p < 0.05 means-Kramer, followed by Tukey post hoc tests.

The two-component blend caught significantly fewer flies than the All_active (P = 0.007), but did not differ from the control (Fig. 9).

Behavioral response of sexually mature Z. cucurbitae females to 2- component, Zeugo_active and All_active blends. Three paraffin oil controls were placed between each treatment. Box plots show the median, interquartile ranges, and outliers of fly catches for the different blends and controls. Number of replicates = 8, with 30 sexually mature female flies per replicate. Different letters indicate significant differences between means at p < 0.05 means-Kramer, followed by Tukey post hoc tests.

Discussion

The melon fly Z. cucurbitae, is among the most destructive horticultural pests worldwide4. Current control strategies that target females mainly depend on food baits, which are broadly attractive to insects and thus affect non-target species, including beneficials18. A species-selective tool that targets the damaging sex is sorely needed19. This study identified antennally active and behaviorally attractive volatiles from different phenological stages of cucurbitaceous host plants of Z. cucurbitae that could be of use in novel control strategies.

Most of the antenna-active compounds identified in this study, including decanal, benzaldehyde, linalool, nonanal, benzyl alcohol, (E)-non-2-enal, and nona-2,6-dien-1-ol, have been previously reported to elicit physiological responses in Z. cucurbitae19,30, and attracted both females and males19. Three of these antenna-active compounds, 1,4-dimethoxybenzene, 4-ethylbenzaldehyde, and propanoic acid, are reported for the first time. Out of the 81 compounds that were individually identifiable, 10 were antenna-active, and 50% of these were shared among C. sativus, C. pepo and C. mixta. This supports the notion of Biasazin et al.31 that the probability of antennal detection by tephritid fruit flies increased for shared volatiles of ripe fruits, even for volatiles from closely related hosts.

Among the antenna-active compounds, linalool, benzaldehyde, and benzyl alcohol have been reported in the floral headspace of more than half of the seed plant species sampled32, while decanal and nonanal are ubiquitous and shared among different plant families32,33. The presence of typical floral volatiles like linalool and methoxybenzene in immature fruit headspace might indicate that decaying flowers carry these volatiles in the course of fruit development. The characteristic cucumber-like odor in cucumber fruits is associated with the aroma of nona-2,6-dien-1-ol and (E)-non-2-enal34. However, these two compounds were only present in flower headspace and absent from both immature and mature fruit headspace, possibly due to their very low release in the latter. Atiama-Nurbel et al.35 reported that both nona-2,6-dien-1-ol and (E)-non-2-enal were present in low amounts in the headspace of mature cucumber pieces. These two compounds increase when the fruit is mechanically ruptured in the presence of oxygen36.

The chemical class of volatiles showed slight differences among the headspaces of flowers. Ketones and terpenoids dominated the flower headspaces of C. sativus and C. pepo, whereas terpenoids and aldehydes predominated in the flower headspace of C. mixta. In all three species studied, ketones dominated the headspace of immature and mature fruit. Previous studies have found that aldehydes and alcohols dominated the headspace of mature cucumbers19,35. The variation in chemical classes might be due to differences in sampling. Damaged and macerated mature cucumber fruits36 release many oxygenated volatiles that are only present in very low amounts in intact fruits (this study). Such variations due to level of damage of the plant material has been reported previously for, for instance, Brassica and Sinapis species37.

In agreement with Siderhurst and Jang19, the physiologically active compounds in this study were dominated by aldehydes, while the number and quantity of esters were very low and responses to these were absent. The headspaces of mini-watermelons Citrullus lanatus and Cucumis melo L. fruits also had low abundances of esters38,39. Esters are typical of mature fruits, and dominate the olfactome of four tephritid fruit fly species31. The amount of ester volatiles increases throughout the ripening of sweet fruits, and synthetic blends of these volatiles were attractive to tephritid females31,40,41. Interestingly, Z. cucurbitae showed lower overall sensitivity to esters compared to other fruit fly species31, indicating that their olfactory receptor repertoire has shifted to other compounds to accommodate the Cucurbitaceae niche, which typically has very low levels of esters (with perhaps the exception of ripe sweet melons which may be abundant in esters)42,43.

Unlike B. dorsalis and C. capitata, which prefer ripe fruits for oviposition44, Z. cucurbitae females preferentially infest flowers, immature, while mature fruits are less preferred1,6,45. This study investigated whether this phenomenon is due to the overlap of odor profiles and antennal sensitivity to those of flowers and immature fruits and mature fruits, while the plants were intact in the field. Indeed, the antenna active compounds from flowers and immature fruits headspace did not differ (Fig. 6), and the flower blend (FB) and immature fruit blend (IFB) attracted a significantly higher number of females than mature fruit blend (MFB). The preference for younger fruit might be due to the hard epidermis of mature fruits6. According to reports, B. dorsalis also showed a low preference for infestation of fruits with a tough pericarp46,47. The difficulty to penetrate the pericarp of ripe fruit may have led to an increased preference for volatiles in earlier development stages, such as aldehydes, to which the melon fly responds. Most aldehydes were high at the early stages of cantaloupe fruits (Cucumis melo var. reticulatus cv. Sol Real) and decreased towards the harvesting stage48. However, mechanically damaging mature fruit has been shown to restore the attraction of gravid Z. cucurbitae females20, which makes sense, as this damage causes the release of large amounts of volatiles typical of early developmental stages, while also offering oviposition sites through bypassing the pericarp.

Insects display defined host preferences, and even within a host, insects are selective in their niche. The olfactory correlate of this behavior is differential attraction to host volatiles that emanate from different niches or phenological stages of the host plant49. For instance, the pea moth Cydia nigricana (Fabricius) can distinguish different phenological stages of its host Pisum sativum L. by headspace extract volatiles in a wind tunnel bioassay, showing a preference for the flowering stage50. Späthe et al.51 also reported that Manduca sexta L. females can rank different host plants and even choose quality plants from individuals of the same species using olfactory cues. Similarly, the west Indian fruit fly Anastrepha obliqua (Macquart) differentiated mango cultivars and ripeness stages using synthetic blends in multilure traps in a semi-natural conditions40. Considering that females are under strong selection to maximize the fitness of their offspring52, immature fruits should be preferable over flowers due to their size and ability to support many larvae to reach adulthood. However, in this study, there was no significant difference between FB and IFB in attracting Z. cucurbitae females. There are several possible explanations for the equal attractiveness of FB and IFB blends in the olfactometer. 1) Flowering and fruiting seasons in cucurbit plants do not show temporal differences; even flowers and harvestable fruits are available on a single plant. Thus, flower volatiles might indicate the presence of a suitable oviposition site for foraging females. In a wind tunnel bioassay, mature females of the tomato fruit fly Neoceratitis cyanescens (Bezzi), which doesn’t oviposit on flowers and infests unripe fruits of Solanaceae, were attracted to flower odor53. Flower odor might thus be used as a cue for the presence of a suitable host at a relatively long distance. Once in close contact with the host, tephritid females use additional sensory inputs to olfaction before accepting the plant part for oviposition50,51,54,55,56. Piñero et al.55 reported that Z. cucurbitae females synergistically use olfaction and vision to locate host plants. Therefore, a bioassay that includes olfaction and vision might reveal whether flowers are equally attractive as immature fruits. 2) Z. cucurbitae might not discriminate between the two blends (FB and IFB) since the physiologically active compounds of flower and immature fruit stages overlapped. This may be ecologically relevant as senescing flowers remain attached to developing immature cucurbits for many days and thus may indicate a suitable oviposition site.

The attraction to different blends, with varying numbers of components according to the natural ratio at different phenological stages of host plants, shows the redundancy of some components in the blends and the behavioral plasticity of the females. Studies on Tephritidae and other insects have reported some physiologically active compounds that were behaviorally redundant41,57,58. The concept that herbivores depend on a ratio of ubiquitous plant compounds to locate hosts or oviposition sites is well documented33,59,60. At the same time, herbivore insects can also rank their hosts and use taxa-specific odors51,61,62. In this study, the IFB that contains ubiquitous volatiles was as attractive as the FB, which contain both ubiquitous volatiles and compounds that are more characteristic of ‘cucumber-like’ aroma in cucurbitaceous fruits (nona-2,6-dien-1-ol and (E)-non-2-enal). Since none of the components of IFB were taxa-specific (to cucurbitaceous plants), our results suggest that Z. cucurbitae females can locate their host plants based on volatiles shared by different plant families at a particular ratio. However, more specific volatiles may play a role in further defining the attractiveness. In a wind tunnel assay, Lobesia botrana (Denis and Shiffermüller) females were attracted to synthetic blends shared by two host plants and blends specific to each host plant. At the same time, higher attraction was recorded when the specific volatiles were added to the shared synthetic blends63.

A controlled and charcoal-filtered laboratory bioassay environment is different from the field, where the insect is exposed to a complex mixture of odors. This may give rise to conflicting results in the performance of blends as observed for the apple fruit moth, Argyresthia conjugella (Zeller)64,65. The interaction of behaviorally relevant blends with background odor can have synergistic or antagonistic effects, and there are examples for both scenarios. Knudsen and Tasin66 reported a difference in the attraction of apple fruit moth A. conjugella, to two-component blends and seven-component blends in the presence of background odor. In the absence of background odor, the two-component blend is equally attractive as the seven-component blend. However, in the presence of background odor at the field, seven-component blend traps attracted three-fold of the two-component blend. On the other hand, background odor enhanced the attraction of moths to a synthetic blend by forming synergy65. Therefore, the performance of the cucurbit flower and fruit-based synthetic blends in attracting females should be evaluated in the field. This study identified behaviorally relevant volatiles from different phenological stages of cucurbitaceous hosts. These findings will contribute to the ongoing efforts to develop female-biased lures for Z. cucurbitae. It will be fascinating to further investigate how generalist tephritids such as B. dorsalis and C. capiata respond physiologically and behaviorally to cucurbit host odor that are low in esters.

Materials and methods

Experimental plants

Cucumis sativus L., Cucurbita pepo L., and Cucurbita mixta L. grown in Alnarp were used for odor sampling. Sampling was performed at the field while the plants were intact. Volatiles were collected from three developmental stages of each species. Stage 1: at a flowering stage when the corollas were still intact; stage 2: when the fruits were young and tender; and stage 3: when the fruits were mature and ready for harvesting.

Experimental insects

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) provided startup material to establish colonies in Sweden and Ethiopia. Flies were held in bugdorm cages (325 × 325 × 325) at 24–28 °C, 60–65% RH, and a 12:12 L:D photoperiod. Honeydew melon (Sweden) or cucumber (Ethiopia) served as the oviposition medium. Adult flies were fed on a standard 1:3 yeast-sugar ratio and provided cotton balls soaked with water.

Odor collection

A 6 cm Teflon tube was filled with 35 mg of Porapak TM type Q 50–80 mesh, with two stoppers and polypropylene wool at both ends. Before collection, the adsorption columns were rinsed with 1 ml of distilled n-hexane and 1 ml of methanol. The column washes were saved in vials and used to assess the cleanliness of the columns. Host flowers and fruits were enclosed in polyamide bags (Toppits Stekpåsar, Mingen, Germany, 35 × 43 cm), and charcoal-filtered air was pumped through the system. The column was placed in the bag and connected to a pump through Teflon tubing. Aerations were run for four hours, and adsorbed compounds were extracted with 0.5 ml of n-hexane into glass vials. The samples were stored at -20 °C until analysis. Each stage of the three cucurbit species was sampled five times.

Gas chromatography coupled electroantennogram (GC-EAD)

The antennal response of sexually mature Z. cucurbitae females to host volatiles was recorded using gas chromatography coupled electroantennogram (GC-EAD) software GC-EAD 2011 (V.1.2.3, Syntech, Kirchzarten, Germany). This software received input from a high impedance GC amplifier interface box (IDAC-2; Syntech, Kirchzarten, Germany), which synced incoming antennal (OpAmp preamplifier probe, Syntech, Kirchzarten, Germany) and GC-Flame Ionization detector (FID) (Agilent Technologies 6890 GC (Santa Clara, CA, USA) signals. The GC was equipped with a DB-Wax column (30 m 0.32 mm 0.25 µm, Agilent Technologies). Hydrogen was used as the carrier gas for the mobile phase. The GC oven temperature was programmed to start at 40 °C (held for 3 min), increase by 10 °C/min–1 to 240 °C, and hold at 240 °C for 5 min. The effluent was split 1:1 between the GC flame ionization detector (FID, at 250 °C) and the EAD. A humidified airstream (1500 ml/min) delivered the effluent to the mounted antenna. Amplified signals from both the FID and EAD were converted to digital signals and displayed on a computer.

Females aged 14–21 days were mounted by immobilizing the fly’s body in a 200 µl micropipette tip. Part of the head and antennae were exposed outside the pipette tip for recording. To create conduction between the silver electrodes and the insect antennae, glass capillaries filled with Beadle-Ephrussi ringer solution were used. The ringer solution had salts dissolved with different concentrations (7.5 g NaCl, 0.35 g KCl, and 0.29 g CaCl dissolved in 1 L of distilled water). The recording electrode was connected to the medio-central part of the antenna, while the reference electrode was inserted into the head of the fly. Antennal depolarizations were analyzed using Syntech data acquisition software. A minimum of three repeatable recordings were conducted for each of the three cucurbit plant species and the three developmental stages.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS)

Samples were analyzed individually by GC/mass spectrometry (MS) using an Agilent 6890/ 5975 GC–MS system with two different columns: a polar DB-Wax and a non-polar HP-5 (both Agilent), each 30 m × 0.25 mm id × 0.25 µm film thickness. Then, samples were pooled after confirming their similarity. The use of both columns enabled complementary separation of compounds, as some compounds that co-elute on one column could be resolved on the other. This approach ensured a more comprehensive identification of volatile compounds. Kovats alkanes (c8–c20) were injected under the same conditions to calculate Kovats retention indices (KI) for the detected compounds. Helium was used as the carrier gas, and the GC temperature was set the same as in the GC-EAD. The peaks were identified by comparing their mass spectra and Kovats retention indices (KI) with the NIST14 database and published values. For estimating the relative amont of compounds, 10 ng of heptyl acetate (Cas # 112-06-1) was added as an internal standard to the pooled headspace extracts. The relative amount of each analyte in the pooled samples was determined by comparing the peak areas of the analyte of interest to the peak area of the internal standard. Then, amount of analytes in the non-polar column was used for further analysis, including comparisons across phenological stages, as most of the analytes were well separated. Further, the pooled samples were used for electrophysiological assay.

Description of six choice olfactomete

The six-choice olfactometer was made up of a reinforced glass cage (420 mm × 420 mm × 420 mm3) and was developed by Tephri Group at SLU, Alnarp. It was described and used by Biasazin et al.31 to evaluate the attraction of tephritid fruit flies to fruit volatiles and different synthetic blends. Later, Figueroa67 used this olfactometer to evaluate the attraction of fermentation products and repellence of plant essential oils against C. capitata.

The olfactometer setup had six circular openings on its top surface, each 70 mm in diameter. Fitted onto these openings are conical glasses with 10 mm holes at the aperture, providing entry points for the flies. At the top of the six circular openings, two cylindrical glasses were positioned, separated by a glass plate with a 2 mm opening to facilitate air passage. The upper cylinder housed the odor source, while the lower cylinder functioned as a collection chamber for flies that had made a choice (Fig. 10b). A single glass plate encompassing six 5-mm holes served both as a conduit for Teflon tubing and a cover for all six chambers. A pump-generated air stream, charcoal-filtered and humidified, was directed to reach each of the chambers at a 0.5 l/min flow rate. Positioned centrally at the top was the light source, strategically placed to minimize bias. Teflon tubing was used throughout the system, and the setup contained five large holes with a 120 mm diameter on the sides and bottom part of the cube, used for releasing and collecting flies (Fig. 10a).

Source67

(a) The six-choice olfactometer setup was used to compare the attractiveness of different cucurbitaceous host odor-based blends to Z. cucurbitae females. (b) Close-up view of the fly-catching and odor-source glass cylinders.

Electrophysiologically active synthetic compounds were diluted to a 10–4 concentration and prepared according to their respective ratios in the headspace. Paraffin oil (prepared by Fine Chemical G. T. PLC, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia) was used to formulate the blends (Table 1). Prior to the experiments, flies underwent an 18 h starvation period with access to water only. Thirty sexually mature females were released for each experiment, with the positions of the treatments rotated to mitigate any potential biases. A volume of 10 µl from each treatment was placed in a plastic bottle cap with a diameter of 30 mm and a height of 10.2 mm.

Bioassay experiments

Experiment one

A blend of antenna-active volatile compounds was prepared for each stage based on the ratio of the components found in the headspace. Although most of the antenna-active components of flowers and immature fruits overlap in presence, the ratio of the components in the headspace varied. Therefore, the blends were prepared to reflect the specific ratio characteristics of each stage. The flower blend (FB) comprised nine compounds including decanal, 1,4-dimethoxybenzene, nona-2,6-dien-1-ol, linalool, benzyl alcohol, benzaldehyde, (E)-non-2-enal, nonanal and propanoic acid, in the following ratio of 55:32:27:18:14:6: 6:0.5:0.1. The immature fruit blend (IFB) contained six components, including linalool, benzyl alcohol, benzaldehyde, nonanal, 4-ethylbenzaldehyde, and propanoic acid in the ratio of 108:114:8:5:4:1. The mature fruit blend (MFB) contained only two components: nonanal and benzaldehyde in a ratio of 29:1, respectively (Table 1). This experiment compared the response of females Z. cucurbitae to the three blends (FB, IFB and MFB) in a 6-choice olfactometer assay.

Experiment two

In the second experiment, three additional blends were formulated. The first blend, termed “All_active,” encompassed all antenna-active compounds. The second blend, termed “Tephri_active,” consisted of compounds identified as bioactive in our studies and previously reported as attractive in other Tephritidae fruit flies. The third blend, termed “Zeugo_active,” consisted of compounds that are antenna-active in our assays and have been reported as attractants only in Z. cucurbitae. These compounds contribute to a distinctive cucumber-like aroma34,68. For each blend, the compounds were prepared in a ratio similar to those found in the headspace of immature fruits. Additionally, compounds exclusively present in the headspace of flowers were incorporated at the ratio observed in flower headspace.

The All_active blend contained all the synthetically confirmed antenna-active compounds from the three cucurbit species. Decanal, 1,4-dimethoxybenzene, nona-2,6-dien-1-ol, benzyl alcohol, linalool, (E)-non-2-enal, 4-ethylbenzaldehyde, benzaldehyde, nonanal and propanoic acid at the ratio of 152:90:76:32:30:16:2:2:1:1, respectively. The Tephri_active blend contained antenna-active components that elicited response from flowers and fruits, excluding two compounds (propanoic acid and 4-ethylbenzaldehyde) from the All_active blend. These exclusions were made as these two compounds were not previously reported in the attraction of tephritid fruit flies, either individually or synergistically with other compounds. The components of the Tephri_active blend include decanal, 1,4-dimethoxybenzene, nona-2,6-dien-1-ol, benzyl alcohol, linalool, (E)-non-2-enal, benzaldehyde, and nonanal at the ratio of 152: 90: 76: 32: 30: 16: 2: 1, respectively. The Zeugo_active blend contains decanal, nona-2,6-dien-1-ol, benzyl alcohol, (E)-non-2-enal and nonanal are mixed at the ratio of 152: 76: 32: 16: 1, respectively (Table 1).

Experiment three

The two-component blend was compared with the Zeugo_active and All_active blends. The two-component blend is composed of nona-2,6-dien-1-ol and (E)-non-2-enal, which are known to be released upon mechanical damage of cucurbit fruits, and are among those compounds responsible for the distinctive cucumber-like aroma34,68. The ratio of the blends was similar to those in experiments two and three (Table 1).

Data analysis

Generalized linear model (GLM)-ANOVA fitted with Poisson distribution (for experiments 1 and 2) and gaussian distribution (for experiment 3) were carried out to compare the mean response of females to different synthetic blends in the six-choice olfactometer. Emmeans package was used for pair-wise mean comparison and mean separation (Tukey Test). Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis using Jaccard dissimilarity index in vegan package was used to compare similarity in the headspaces of the three species (C. sativus, C. pepo and C. mixta) and the three developmental stages (flower, immature fruit and mature fruit). The average relative response of EAD amplitudes was computed using three replicates of antennal responses of female Z. cucurbitae. To normalize the responses, each response in each EAD trace was divided by the weighted mean of all the responses in that trace. The weighted mean was obtained by using the back transformed (exp) average of the ln transformed depolarization values of each response in that trace. Then, normalized responses were averaged across traces by dividing them by the total sum of average normalized responses, in order to scale the responses from 0 to 1 as seen in the heatmap. Moreover, regression analysis was conducted to determine whether the amount of volatile had an impact on response strength. To produce the heatmap, bar chart, box plots, and NMDS plots; ggplot2 package in R software version 4.1.2 was used.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dhillon, M. K., Singh, R., Naresh, J. S. & Sharma, H. C. The melon fruit fly, Bactrocera cucurbitae: A review of its biology and management. J. Insect Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/jis/5.1.40 (2005).

White, I. & Elson-Harris, M. Fruit Flies of Economic Significance: Their Identification and Bionomics (CABI, 1992). https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851987903.0000.

Vayssières, J.-F., Rey, J.-Y. & Traoré, L. Distribution and host plants of Bactrocera cucurbitae in West and Central Africa. Fruits 62, 391–396 (2007).

De Meyer, M. et al. A review of the current knowledge on Zeugodacus cucurbitae (Coquillett) (Diptera, Tephritidae) in Africa, with a list of species included in Zeugodacus. Zookeys 540, 539–557 (2015).

Mcquate, G. T., Liquido, N. J. & Nakamichi, K. A. A. Annotated World Bibliography of Host Plants of the Melon Fly, Bactrocera cucurbitae (Coquillett) (Diptera: Tephritidae). Insecta Mundia (2017).

Mwatawala, M. et al. Preference of Zeugodacus cucurbitae (Coquillett) for three commercial fruit vegetable hosts in natural and semi natural conditions. Fruits 70, 333–339 (2015).

Ryckewaert, P., Deguine, J. P., Brévault, T. & Vayssières, J. F. Fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) on vegetable crops in Reunion Island (Indian Ocean): State of knowledge, control+ methods and prospects for management. Fruits 65, 113–130 (2010).

Deguine, J. P. et al. Agroecological management of cucurbit-infesting fruit fly: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 35, 937–965 (2015).

Bourguet, D. & Guillemaud, T. The hidden and external costs of pesticide use. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews (ed. Lichtfouse, E.) 35–120 (Springer International Publishing, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26777-7_2.

Sheahan, M., Barrett, C. B. & Goldvale, C. Human health and pesticide use in Sub-Saharan Africa. Agric. Econ. (United Kingdom) 48, 27–41 (2017).

Jang, E. B. et al. Targeted trapping, bait-spray, sanitation, sterile-male, and parasitoid releases in an areawide integrated melon fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) control program in Hawaii. Am. Entomol. 54, 240–250 (2008).

Lloyd, A. C. et al. Area-wide management of fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) in the Central Burnett district of Queensland. Australia. Crop Prot. 29, 462–469 (2010).

Vargas, R. I. et al. Area-wide suppression of the mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata, and the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis, in Kamuela Hawaii. J. Insect Sci. 10, 1–17 (2010).

Vargas, R. I., Piñero, J. C. & Leblanc, L. An overview of pest species of Bactrocera fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) and the integration of biopesticides with other biological approaches for their management with a focus on the pacific region. Insects 6, 297–318 (2015).

Niassy, S. et al. Insight on fruit fly IPM technology uptake and barriers to scaling in Africa. Sustainability 14, 29–54 (2022).

El-Sayed, A. M., Suckling, D. M., Byers, J. A., Jang, E. B. & Wearing, C. H. Potential of ‘Lure and kill’ in long-term pest management and eradication of invasive species. J. Econ. Entomol. 102, 815–835 (2009).

Tan, K. H., Nishida, R., Jang, E. B. & Shelly, T. E. Pheromones, male lures, and trapping of tephritid fruit flies. In Trapping and the Detection, Control, and Regulation of Tephritid Fruit Flies: Lures, Area-Wide Programs, and Trade Implications (eds Shelly, T. et al.) 15–74 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9193-9_2.

Epsky, N. D., Kendra, P. E. & Schnell, E. Q. History and development of food-based attractants. In Trapping and the Detection, Control, and Regulation of Tephritid Fruit Flies: Lures, Area-Wide Programs, And Trade Implications (eds Shelly, T. et al.) 75–118 (Springer Netherlands, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9193-9_3.

Siderhurst, M. S. & Jang, E. B. Cucumber volatile blend attractive to female melon fly, Bactrocera cucurbitae (Coquillett). J. Chem. Ecol. 36, 699–708 (2010).

Miller, N. W., Vargas, R. I., Prokopy, R. J. & Mackey, B. E. State-dependent attractiveness of protein bait and host fruit odor to Bactrocera cucurbitae (Diptera: Tephritidae) females. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 97, 1063–1068 (2004).

Quilici, S., Atiama-Nurbel, T. & Brévault, T. Plant odors as fruit fly attractants. In Trapping and the Detection, Control, and Regulation of Tephritid Fruit Flies: Lures, Area-Wide Programs, And Trade Implications (eds Shelly, T. et al.) 119–144 (Springer Netherlands, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9193-9_4.

Prokopy, R. J., Resilva, S. S. & Vargas, R. I. Post-alighting behavior of Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) on odor-baited traps. Florida Entomol. 79, 422–428 (1996).

Jang, E. B., McInnis, D. O., Kurashima, R. & Carvalho, L. A. Behavioural switch of female Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata: Mating and oviposition activity in outdoor field cages in Hawaii. Agric. For. Entomol. 1, 179–184 (1999).

Cornelius, M. L., Nergel, L., Duan, J. J. & Messing, R. H. Responses of female oriental fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) to protein and host fruit odors in field cage and open field tests. Environ. Entomol. 29, 14–19 (2000).

Roh, G.-H., Kendra, P. E. & Cha, D. H. Preferential attraction of oviposition-ready oriental fruit flies to host fruit odor over protein food odor. Insects 12, 909 (2021).

Zhang, A. et al. Identification of a new blend of apple volatiles attractive to the apple maggot Rhagoletis pomonella. J. Chem. Ecol. 25, 1221–1232 (1999).

Royer, J. E., De Faveri, S. G., Lowe, G. E. & Wright, C. L. Cucumber volatile blend, a promising female-biased lure for Bactrocera cucumis (French 1907) (Diptera: Tephritidae: Dacinae), a pest fruit fly that does not respond to male attractants Jane. Austral Entomol. 53, 347–352 (2014).

Piñero, J. C., Jácome, I., Vargas, R. & Prokopy, R. J. Response of female melon fly, Bactrocera cucurbitae, to host-associated visual and olfactory stimuli. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 121, 261–269 (2006).

Njuguna, P. K. et al. Cucumber and tomato volatiles: Influence on attraction in the melon fly zeugodacus cucurbitate (Diptera: Tephritidae). J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 8504–8513 (2018).

Shivaramu, S., Parepally, S. K., Chakravarthy, A. K., Pagadala Damodaram, K. J. & Kempraj, V. Ridge gourd volatiles are attractive to gravid female melon fly, Zeugodacus cucurbitae (Coquillett) (Diptera: Tephritidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 146, 539–546 (2022).

Biasazin, T. D., Larsson Herrera, S., Kimbokota, F. & Dekker, T. Translating olfactomes into attractants: Shared volatiles provide attractive bridges for polyphagy in fruit flies. Ecol. Lett. 22, 108–118 (2019).

Knudsen, J. T., Eriksson, R., Gershenzon, J. & Ståhl, B. Diversity and distribution of floral scent. Bot. Rev. 72, 1–120 (2006).

Webster, B., Gezan, S., Bruce, T., Hardie, J. & Pickett, J. Between plant and diurnal variation in quantities and ratios of volatile compounds emitted by Vicia faba plants. Phytochemistry 71, 81–89 (2010).

Forss, D. A. & Ramshaw, E. H. The flavor of cucumbers molecular structure and flavor. J. Food Sci. 27, 90 (1961).

Atiama-Nurbel, T. et al. Volatile constituents of Cucumis sativus: Differences between five tropical cultivars. Chem. Nat. Compd. 51, 771–775 (2015).

Fleming, H. P., Cobb, W. Y., Etchells, J. L. & Bell, T. A. The formation of carbonyl compounds in cucumbers. J. Food Sci. 33, 572–576 (1968).

Tollsten, L. & Bergström, G. Headspace volatiles of whole plants and macerated plant parts of Brassica and Sinapis. Phytochemistry 27, 2073–2077 (1988).

Dima, G., Tripodi, G., Condurso, C. & Verzera, A. Volatile constituents of mini-watermelon fruits. J. Essent. Oil Res. 26, 323–327 (2014).

Majithia, D., Metrani, R., Dhowlaghar, N., Crosby, K. M. & Patil, B. S. Assessment and classification of volatile profiles in melon breeding lines using headspace solid-phase microextraction coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Plants 10(10), 2166. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10102166 (2021).

Neri Benítez-Herrera, L., Cruz-López, L. C., Malo, E. A., Romero-López, A. A. & Rojas, J. C. Olfactory responses of anastrepha obliqua (Diptera: Tephritidae) to mango fruits as influenced by cultivar and ripeness stages. Environ. Entomol. 52, 210–216 (2023).

Cunningham, J. P., Carlsson, M. A., Villa, T. F., Dekker, T. & Clarke, A. R. Do fruit ripening volatiles enable resource specialism in polyphagous fruit flies?. J. Chem. Ecol. 42, 931–940 (2016).

Aubert, C. & Pitrat, M. Volatile compounds in the skin and pulp of queen anne’s pocket melon. J. Agric. Food Chem. 54, 8177–8182 (2006).

Shi, J. et al. Comparative analysis of volatile compounds in thirty nine melon cultivars by headspace solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 316, 126342 (2020).

Clarke, A. R. Why so many polyphagous fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae)? A further contribution to the ‘generalism’ debate. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 120, 245–257 (2017).

Piñero, J. C., Souder, S. K., Cha, D. H., Collignon, R. M. & Vargas, R. I. Age-dependent response of female melon fly, Zeugodacus cucurbitae (Diptera: Tephritidae), to volatiles emitted from damaged host fruits. J. Asia. Pac. Entomol. 24, 759–763 (2021).

Oi, D. H. & Mau, R. F. L. Relationship of fruit ripeness to infestation in ‘sharwil’ avocados by the mediterranean fruit fly and the oriental fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 82, 556–560 (1989).

Rattanapun, W., Amornsak, W. & Clarke, A. R. Bactrocera dorsalis preference for and performance on two mango varieties at three stages of ripeness. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 131, 243–253 (2009).

Boué, S. M., Shih, B. Y., Carter-Wientjes, C. H. & Cleveland, T. E. Identification of volatile compounds in soybean at various developmental stages using solid phase microextraction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51, 4873–4876 (2003).

Piñero, J. C. & Dorn, S. Response of female Oriental fruit moth to volatiles from Apple and Peach trees at three phenological stages. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 131, 67–74 (2009).

Thöming, G., Norli, H. R., Saucke, H. & Knudsen, G. K. Pea plant volatiles guide host location behaviour in the pea moth. Arthropod. Plant. Interact. 8, 109–122 (2014).

Späthe, A. et al. Plant species-and status-specific odorant blends guide oviposition choice in the moth Manduca sexta. Chem. Senses 38, 147–159 (2013).

Jaenike, J. Host specialization in phytophagous insects. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 21, 243–273 (1990).

Brevault, T. & Quilici, S. Flower and fruit volatiles assist host-plant location in the Tomato fruit fly Neoceratitis cyanescens. Physiol. Entomol. 35, 9–18 (2010).

Reeves, J. L. Vision should not be overlooked as an important sensory modality for finding host plants. Environ. Entomol. 40, 855–863 (2011).

Piñero, J. C., Souder, S. K. & Vargas, R. I. Vision-mediated exploitation of a novel host plant by a tephritid fruit fly. PLoS ONE 12, 1–17 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Behavioral and genomic divergence between a generalist and a specialist fly. Cell Rep. 41, 111654 (2022).

Tasin, M. et al. Synergism and redundancy in a plant volatile blend attracting grapevine moth females. Phytochemistry 68, 203–209 (2007).

Cortés-Martínez, F., Cruz-López, L., Liedo, P. & Rojas, J. C. The ripeness stage but not the cultivar influences the attraction of Anastrepha obliqua to guava. Chemoecology 31, 115–123 (2021).

Bengtsson, M. et al. Plant volatiles mediate attraction to host and non-host plant in apple fruit moth. Argyresthia conjugella. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 118, 77–85 (2006).

Bruce, T. J. A. & Pickett, J. A. Perception of plant volatile blends by herbivorous insects - Finding the right mix. Phytochemistry 72, 1605–1611 (2011).

Conchou, L., Anderson, P. & Birgersson, G. Host plant species differentiation in a polyphagous moth: olfaction is enough. J. Chem. Ecol. 43, 794–805 (2017).

Silva, R. & Clarke, A. R. The, “sequential cues hypothesis”: A conceptual model to explain host location and ranking by polyphagous herbivores. Insect Sci. 27, 1136–1147 (2020).

Tasin, M. et al. Attraction of female grapevine moth to common and specific olfactory cues from 2 host plants. Chem. Senses 35, 57–64 (2010).

Cai, X. et al. Field background odour should be taken into account when formulating a pest attractant based on plant volatiles. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–10 (2017).

Knudsen, G. K., Norli, H. R. & Tasin, M. The ratio between field attractive and background volatiles encodes host-plant recognition in a specialist moth. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 315184 (2017).

Knudsen, G. K. & Tasin, M. Spotting the invaders: A monitoring system based on plant volatiles to forecast apple fruit moth attacks in apple orchards. Basic Appl. Ecol. 16, 354–364 (2015).

Figueroa, C. I. A. Ethological control of the Mediterranean fruit fly Ceratitis capitata (Wied .). (Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae, (2019: 45)., 2019).

Kemp, T. R., Knavel, D. E. & Stoltz, L. P. Identification of some volatile compounds from cucumber. J. Agric. Food Chem. 22, 717–718 (1974).

Acknowledgements

We thank AAU, Department of Zoological Sciences, for financial support from the post-graduate program and Thematic Research Project, Grant No. TR/038/2021 and for facilitating this study. The study was supported by two grants from the Swedish research council (VR), 2019-04421 (TDB), and Swedish Research Links grants 2020-05344 (TD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.B., Y.W.,T.D.B. and T.D. conceptualization. Y.B. and T.D.B, data Collection. Y.B. and T.D.B data Analysis. Y.B, Writing the draft, and all authors, reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baraki, Y., Woldehawariat, Y., Dekker, T. et al. Phenological stage dependent sensory and behavioral responses of Zeugodacus cucurbitae (Coquillett) to cucurbit volatiles. Sci Rep 15, 18072 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94928-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94928-9