Abstract

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) plays a critical role in immune tolerance and evasion within the tumor microenvironment, and anti-PD-1 immunotherapy has shown efficacy in treating advanced melanoma. However, response rates vary significantly among patients, necessitating the identification of reliable biomarkers to predict treatment efficacy. Based on within-sample relative expression orderings, we analyzed RNA sequencing data from melanoma patients to construct a predictive model comprising gene pairs associated with treatment response. The model’s performance was validated across multiple independent datasets and assessed for correlations with immune infiltration and survival outcomes. The constructed 15-pair model achieved a prediction accuracy of 100% in training datasets and 89.47% in validation sets. Validation in melanoma patients lacking treatment response data revealed significant differences between predicted responders and non-responders across datasets, with the model being an independent prognostic factor. Increased immune cell infiltration was observed in responders, correlating with higher expression levels of key immune checkpoint genes. The relative expression orderings-based model shows promise as a tool for predicting responses to anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients, supporting personalized treatment strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) is an important inhibitory receptor on immune cells1,2. Under normal conditions, PD-1 on T cells binds to programmed cell death-ligand 1(PD-L1) on normal cells, generating immune tolerance, inhibiting T cell activity, and preventing autoimmune reactions3. However, when tumor cells invade the body, they utilize PD-L1 to bind to PD-1, suppressing T-cell proliferation and activation, ultimately leading to immune evasion4. Notably, PD-1 is found on T cells, macrophages, B lymphocytes, and dendritic cells, suggesting a crucial role for PD-1 in regulating the tumor immune microenvironment and anti-tumor immunity5.

To overcome immune evasion by tumor cells, researchers have made significant efforts to develop anti-PD-1 immunotherapy drugs to prevent the interaction between PD-1 on immune cells and its ligand on tumor cells6. Currently, anti-PD-1 antibodies like nivolumab and pembrolizumab, approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, have improved patient outcomes, such as better treatment response, progression-free survival, and overall survival in patients with advanced cancer7. However, some patients develop resistance to PD-1 inhibitors, which may be attributed to several mechanisms, including the deficiency of strong cancer antigens or epitopes recognized by T cells, limited activation of cancer-specific T cells, insufficient infiltration of T cells into tumors, downregulation of the major histocompatibility complex on cancer cells, and the presence of immunosuppressive factors and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment8.

Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy has also demonstrated significant efficacy in treating advanced melanoma6,8, a highly invasive malignancy that occurs in the skin, oral cavity, intestines, and eyes9. Approximately 40% of melanoma patients completely or partially respond to this therapy, with significant tumor reduction or disappearance10. However, its effectiveness varies due to tumor and patient heterogeneity, with some patients not benefiting and others experiencing disease progression11. Cutaneous melanoma, which is closely linked to ultraviolet radiation exposure, has seen significant improvements in patient survival with the widespread use of PD-1 inhibitors, with median survival increasing to 23 months and an objective response rate of 40%12. In contrast, uveal melanoma, which originates in the choroid of the eye, exhibits unique biological characteristics and molecular genetic changes that distinguish it from cutaneous melanoma in terms of pathogenesis, metastasis patterns, and prognosis13. Patients with uveal melanoma generally have a poorer response to PD-1 inhibitors and face a worse prognosis due to the highly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment14. This variability, alongside the high cost of anti-PD-1 therapies, highlights a critical need for developing reliable biomarkers to predict treatment efficacy. Given that cutaneous melanoma is the most prevalent type of melanoma, accounting for the majority of cases, this study specifically focuses on patients with cutaneous melanoma to investigate the predictive impact of anti-PD-1 therapy.

Research has established a link between the effectiveness of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy and various molecular biomarkers, including the expression levels of PD-L1, LAG-3, and CXCR3, tumor mutation burden, extent of tumor lymphocyte infiltration, and presence of neoantigens15,16. However, the application of these biomarkers is hindered by challenges such as variability in gene expression and technical inconsistencies affecting reproducibility across different studies and platforms17. Therefore, future studies should explore more stable and reliable biomarkers for predicting efficacy.

During the disease process, changes in gene expression levels can disrupt the relative expression orderings (REOs) between genes. Analyzing these perturbations can help uncover molecular biomarkers for disease diagnosis and treatment18. Studies have demonstrated that REOs-based biomarkers offer advantages, such as reducing uncertainties from batch effects and data normalization issues, ensuring data stability and reliability, and simplifying complex gene quantitative information into qualitative data. In cancer prognostic prediction, signatures based on REOs have shown great promise. Yang et al.. developed a REOs-based signature comprising 64 gene pairs to predict prognosis and treatment response in metastatic colorectal cancer patients undergoing bevacizumab therapy19. Similarly, Bu et al. created a prognostic signature using 50 lncRNA pairs to assess the risk of recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma patients after surgery20. Therefore, biomarkers based on REOs are valuable for personalized prediction within a clinical setting. However, it remains unclear whether the REOs-based method can provide additional benefits for predicting the efficacy of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in advanced melanoma.

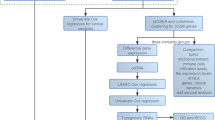

This study explores the correlation between perturbations in gene expression orderings and the response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. The primary objective is to identify potential biomarkers that accurately forecast an individual’s response to treatment. To achieve this, we analyzed an RNA-seq dataset specific to melanoma patients receiving anti-PD-1 immunotherapy using machine learning algorithms. We established a predictive model consisting of 15 gene pairs, demonstrating its effectiveness in predicting response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy across diverse, independent datasets. This model holds promise for facilitating more targeted and personalized treatment strategies for melanoma patients.

Materials and methods

Data source and data preprocessing

This study collected four melanoma datasets from the GEO and TCGA databases (Table 1). Dataset GSE91061 includes pre-treatment and on-treatment metastatic tumor samples, which were collected one week before and on the 29th day of the first cycle after receiving anti-PD-1 treatment. The pre-treatment samples were used for training (referred to as GSE91061_pre), and the on-treatment samples were used for validation (referred to as GSE91061_on). The GSE115821, GSE22153, and TCGA-SKCM datasets were served as independent validation sets. GSE115821 also contains pre-treatment and on-treatment metastatic tumor samples, collected up to one day before and up to 90 days after the start of treatment, while GSE22153 and TCGA-SKCM do not include anti-PD-1 treatment information. For melanoma patients, the response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy is categorized into complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD) according to the Solid Tumor Response Evaluation Criteria (version 1.1). In this study, patients with CR and PR were classified as responders, while those with PD were considered non-responders. The classification of SD as non-responders is debated21. Therefore, SD samples were excluded from the training set.

To enhance the reliability of the data, we employed a comprehensive preprocessing approach. First, we omitted genes expressed in less than 70% of the samples. Missing values were estimated using k Nearest Neighbors (k = 1). Next, we excluded all healthy samples from the TCGA-SKCM data. Lastly, we removed all non-protein-coding genes from the datasets. Gene expression analyses in the GSE22153 dataset were performed using Illumina BeadArrays, while in the other datasets were analyzed using different Illumina sequencing platforms. The array data were normalized using a cubic spline procedure and log2 transformed, and the RNA-sequencing data (FPKM values) were normalized to log2(FPKM + 1). To integrate findings across studies, we identified and selected genes consistently present across different datasets.

Identification of candidate predictive gene pairs

In the training set, genes were paired to form gene pairs, each consisting of two genes with expression levels denoted as genea and geneb. We defined the REOs of a gene pair within a sample as genea > geneb or genea ≤ geneb. For example, consider the gene pair ABCC5 and ARID1B: in non-responder samples, ABCC5 was mostly expressed at higher levels than ARID1B (ABCC5 > ARID1B, Fig.S1a). In responder samples, the trend of REOs was reversed, with ARID1B often expressed at higher levels than ABCC5 (ARID1B > ABCC5, Fig.S1b). We established the reference pattern of REOs as genea>geneb in non-responder samples (or genea≤geneb in responder samples). We then compared the within-sample REOs in non-responders to those in responders to identify candidate predictive gene pairs that demonstrated significant REOs reversals.

Identifying reference stable gene pairs in non-responder samples

A gene pair is termed a reference stable gene pair if the proportion of samples (p) showing REOs consistent with the reference pattern exceeds a predetermined threshold (Pt). The proportion P is calculated as k/m × 100%, where k represents the number of samples exhibiting reference pattern and m is the total number of samples in the group. In this study, Pt was set at 80% to ensure an adequate number of gene pairs and achieve high stability.

Identifying reversed gene pairs in responder samples

For each reference stable gene pair, the numbers of non-responder and responder samples showing the REOs of genea> geneb and genea ≤geneb can be denoted as n1, n2, and m1, m2, respectively. Fisher’s exact test was employed to determine whether the distribution of REOs in non-responders differed from that in responder samples. We used the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method to control the FDR across all tested gene pairs and thus minimize type I errors. A gene pair’s REOs was considered significantly reversed and defined as a reversed gene pair if the adjusted p-value was less than 0.05.

Determining candidate predictive gene pairs

For a reversed gene pair, the reversal rate △P was calculated using the formula △P = Pnon−responder (genea>geneb) - Presponder (genea>geneb). A greater △P indicates a larger difference in the REOs of the gene pair. △P = 1 indicates that the REOs of the gene pair in all non-responders are genea>geneb, while in all responders, they are genea≤geneb. A reversed gene pair with a ΔP value exceeding a threshold △Pt is identified as a candidate predictive gene pair. Here we chose △Pt = 70% to guarantee significant reversal patterns in REOs and exclude gene pairs with less consistent REOs patterns within group samples.

Determination of the predictive biomarker pairs

In the training set, for each candidate predictive gene pair, we counted the number of samples that matched the reference pattern to calculate the sample coverage of the gene pair using Eq. 1.

To identify gene pairs that can predict efficacy, we employed a greedy algorithm to find the combination of gene pairs that achieves maximum sample coverage. Initially, each candidate predictive gene pair served as a starting combination. We then sequentially added each remaining candidate gene pair to the current combination. After incorporating each gene pair, we recalculated the sample coverage of the new combination. This process continued until adding an additional gene pair no longer enhanced the sample coverage. The resultant combinations were identified as those with maximum sample coverage for each candidate predictive gene pair.

We calculated the frequency of occurrence of gene pairs across all combinations. Higher frequencies reflect the importance of the candidate gene pair. The frequencies were sorted from largest to smallest, and the top k pairs with the highest frequency were selected sequentially, where k is a predefined parameter ranging from 1 to n, with n being the total number of candidate gene pairs. The geometric mean of the negative predictive value (NPV) and positive predictive value (PPV) of the top k candidate gene pairs was calculated. The top k candidate gene pairs that first reached the maximum geometric mean and stabilized were selected to construct the final predictive model. Then, we use the “power.fisher.test” function from “statmod” package to estimate the power of each predictive pair to discriminate the REO patterns between non-responders and responders.

To predict a sample, we consider n gene pairs, represented as (geneia, geneib) for i = 1 to n. Here, geneia and geneib represent the two genes in the ith gene pair in the predictive model. We define a function f(i) to quantify the difference between the gene pairs, expressed as: f(i) = genei.a.−geneib. Next, we establish a classification function C defined as follows:

According to the voting rule, if the number of gene pairs exhibiting genea>geneb exceeds half, the sample is categorized as a non-responder; otherwise, it is categorized as a responder.

Validation of the predictive model

To evaluate the predictive efficacy, we meticulously analyzed its performance across various datasets. We assessed the model’s accuracy (ACC), specificity (SP), sensitivity (SE), PPV and NPV using the training set GSE91061_pre and validation sets GSE91061_on, GSE115821_pre, and GSE115821_on. This comprehensive evaluation aimed to determine the model’s effectiveness in discriminating between responders and non-responders to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy.

KEGG pathway analysis and GO functional enrichment analysis of the genes involved in the model were performed by the R package “clusterProfiler” with default parameters.

Since the GSE22153 and TCGA-SKCM datasets lack information on response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, the model’s validity was further interrogated through survival analysis, immune infiltration assessment, and examination of immune checkpoint-related gene expression. These approaches were designed to indirectly validate the model by exploring correlated outcomes.

We examined survival differences between the model-predicted responder and non-responder groups using Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival analysis, employing the “survival” and “survminer” R packages. Additionally, we performed a multivariate Cox regression analysis, incorporating variables such as age, gender and our model’s classifications, to determine the influence of individual prognostic factors on survival in melanoma patients. To verify the Cox proportional hazard model, we performed a Schoenfeld residual analysis. This involved plotting scaled residuals against time and testing their relationship. If no clear trend was observed and the p-value exceeded 0.05, the proportional risk assumption was considered valid. Schoenfeld residuals plots for each variable were generated using the “survival” R packages.

The assessment of immune cell infiltration levels in the predicted subgroups within the TCGA-SKCM and GSE22153 datasets employed the single sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) algorithm. This algorithm evaluates the relative abundance of various immune cell types in the samples, allowing for comparisons of immune cell infiltration between the responder and non-responder groups delineated by our model.

We examined the expression of ten published immune checkpoint-related genes (CD274 (PD-1)22, CTLA-423, CXCR324, LAG325, PDCD1 (PD-L1)26, CD8027, ICOS28, IFNG29, IL1030, TNFRSF931) in the model-predicted subgroups. A Wilcoxon test was performed to determine significant gene expression differences.

Comparison of the model with published predictive models

In this study, we compared out model with the published random forest model by Wang et al.32 and the TIDE model developed by Jiang et al.33. To ensure the models were comparable, we selected the TCGA-SKCM dataset, which had previously been utilized as both a validation set by Wang et al.. and a training set by Jiang et al.. for this analysis. We performed KM survival analysis for the two subgroups predicted by each model, subsequently comparing the survival curves using Log-rank test to determine p-values.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses in this study were performed with R 4.4.0 software.

Results

Constructing the 15-pair model based on within-sample reos

In this study, we analyzed pre-treatment melanoma samples from GSE91061 to identify candidate gene pairs for predicting response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy response (see Methods). Samples categorized as PD were used as non-responders to establish reference stable gene pairs.

Using a threshold of 80%, we obtained 83,634,592 stable gene pairs. Among these, 453,714 gene pairs showed significant reversal REOs in responder (PR or CR) samples (FDR < 5%, Fisher’s exact test). By applying a reversal rate threshold ΔPt of 70%, we identified 320 reversed gene pairs as candidate predictive gene pairs.

Using these candidates, we employed a greedy algorithm to construct a model of 15 predictive biomarker pairs, referred to as 15-pair (Table 2). For each of the 15 gene pairs in the model, we calculated the statistical power to detect REO reversal patterns between responders and non-responders using the power.fisher.test function (see Methods). All pairs demonstrated greater than 99% power (α = 0.05) to reject the null hypothesis (Table 2), based on the observed effect sizes in our cohorts (pre-treatment: 10 responders vs. 23 non-responders). The classification criteria are based on voting rules, where a sample is classified as a non-responder if the number of gene pairs exhibiting the reference REOs pattern is ≥ 8. The classification criteria are consistent across different datasets.

Functional enrichment analysis of the 27 genes involved in 15-pair showed no significant pathways. To directly explore their biological relevance, we interrogated these genes using GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/). Key genes in the model are mechanistically linked to melanoma progression and immune evasion (Supplementary Table S1). For example, ARID1B mutation leads to impaired DNA damage response and repair, altered chromatin accessibility, resulting in aberrant expression of tumor-associated antigens and reduced immunogenicity of tumor cells34. SOAT1 is positively regulated and provided several immune-related functions, which included cytokine production, adaptive immune response, cell activation involved in immune response35. KNOP1 is associated with cell cycle and MAPK-related pathways, which regulate cellular activities during cancer development, including cell proliferation, apoptosis and immune escape36. NUP43 promotes PD-L1/nPD-L1/PD-L1 feedback loop via TM4SF1/JAK/STAT3 pathway in cancer progression and metastasis37. THOC2 reduction repressed melanoma cell proliferation and invasion, and induced cell apoptosis in vitro38. These findings collectively highlight the 15-pair model’s mechanistic basis in tumor-immune interactions, linking genomic instability (ARID1B), immune dysregulation (SOAT1, NUP43), and oncogenic signaling (KNOP1, THOC2) to melanoma progression and immunotherapy outcomes.

The prediction accuracy of the 15-pair model was 100%, and the AUC was 100% (95%CI:1–1), F1-score was 100% in the training set GSE91061_pre. In the validation set GSE91061_on, the prediction accuracy was 89.47% and the AUC was 91.8%(95%CI:0.815-1), and F1-score was 84.6%. Both validation sets, GSE115821_pre and GSE115821_on, achieved a prediction accuracy of 100% (Table 3).

These results suggest the excellent prediction efficacy of the 15-pair for forecasting response to anti-PD-1 treatment in melanoma patients.

Validation of the 15-pair model in melanoma patients lacking treatment response information

In validating the 15-pair model for melanoma patients lacking treatment response data, we analyzed the differences in survival analysis, immune infiltration levels, and immune checkpoint-related gene expression between the two groups predicted in TCGA-SKCM and GSE22153 datasets.

15-pair model as an independent prognostic factor for anti-PD-1 immunotherapy response in melanoma

After removing samples with a survival time of under one month, we had 451 samples in TCGA-SKCM and 47 in GSE22153. In TCGA-SKCM, 193 samples were predicted as non-responders and 258 as responders. In GSE22153, 31 were non-responders, and 16 were responders. KM survival curves showed significant survival differences in both datasets (Fig. 1a and b), with non-responders exhibiting poorer survival (p < 0.05, Log-rank test).

Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival analysis and Cox regression analysis for responder and non-responder groups. (a,b) KM survival analysis comparing survival differences between responders and non-responders predicted in the TCGA-SKCM and GSE22153 datasets. (c,d) Forest plot based on multivariate Cox regression analysis using the TCGA-SKCM and GSE22153 datasets. (e,f) Survival differences between responders and non-responders predicted by the random forest model and TIDE model in the TCGA dataset. The light shaded area displays the confidence interval of the survival curve. NR: non-responders; R: responders; CI: confidence interval.

Our analysis of the Schoenfeld residuals revealed that the tests for age, gender, and the 15-pair model did not show significant time dependence (p > 0.05). Furthermore, the smooth line of the residual diagram was basically parallel to the time axis, indicating that the covariate effect did not change with time (Fig.S2 a-b). These results showed that all covariates adhere to the proportional hazards assumption. The multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that the 15-pair model was significantly associated with the overall survival of patients in both datasets (HR = 9.5, 95% CI: 3.44–26.5, p-value < 0.001, Fig. 1c; HR = 51.1, 95% CI: 2.73–954.9, p-value = 0.008, Fig. 1d), indicating it is an independent prognostic factor for anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma.

Relation between the 15-pair model and tumor microenvironment

To investigate the association between the 15-pair model and immune infiltration, we assessed 28 immune subpopulations. The ssGSEA analysis of the TCGA-SKCM dataset revealed significant differences in the proportions of T cells, B cells, macrophages, eosinophils, neutrophils, and natural killer cells between the responder and non-responder groups (p < 0.05, Wilcoxon test, Fig. 2a), with the responder group showing higher infiltration levels. In the GSE22153 dataset, significant differences in the infiltration levels of B cells, macrophages, eosinophils, regulatory T cells, and natural killer cells were also observed between the two groups predicted by the 15-pair model (p < 0.05, Wilcoxon test, Fig. 2b), again with the responder group showing higher infiltration levels.

Radar plot showing differences in immune subpopulation infiltration between responder and non-responder groups. (a) TCGA-SKCM. (b) GSE22153. p-values were estimated using the Wilcoxon test: *indicates p < 0.05; **indicates p < 0.01; ***indicates p < 0.001; ****indicates p < 0.0001. NR: non-responders; R: responders.

15-pair as a predictor of immunotherapeutic responses

Given the significant difference in immune infiltration between the responder and non-responder groups, we investigated the predictive capability of the 15-pair model for immunotherapeutic responses.

In the TCGA-SKCM dataset, analysis of the expression values of 10 published immune checkpoints revealed that CD274, CTLA-4, CXCR3, LAG3, PDCD1, CD80, ICOS, IFNG, IL10, and TNFRSF9 were significantly higher in the responder group compared to the non-responder group (p < 0.05, Wilcoxon test, Fig. 3a). Due to the unavailability of CD274 and IFNG in GSE22153, we focused on the remaining eight immune checkpoints. The results showed that, except LAG3, the expression values of all seven genes were significantly higher in the responder group relative to the non-responder group (p < 0.05, Wilcoxon test, Fig. 3b). For LAG3, there was a trend towards a significant difference (p = 0.07), hinting at a potential role for LAG3 in immune responses.

Comparison of the 15-pair model with previously established predictive models

We evaluated the predictive performance of 15-pair using the TCGA-SKCM dataset, comparing it against the random forest model established by Wang et al. and the TIDE model proposed by Jiang et al.

Wang’s model showed a significant difference in survival between the responder and non-responder groups (p-value = 0.006, Log-rank test, Fig. 1e). In contrast, Jiang’s model did not exhibit a significant difference (p = 0.27, Log-rank test, Fig. 1f). Notably, the 15-pair model demonstrated a more significant difference in survival between these two groups (p = 0.00074, Fig. 1a) compared to both Wang and Jiang’s models.

Discussion

In our exploring predictive biomarkers for melanoma anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, this study analyzed the reversibility of REOs in responders and non-responders using gene expression data. We identified a 15-pair model exhibiting notable predictive accuracy, demonstrating effectiveness across four distinct datasets with predictive accuracies of 100%, 89.47%, 100%, and 100%. These results suggest the model’s potential in forecasting anti-PD-1 immunotherapeutic response in melanoma patients.

To justify the sample sizes used in our study, we conducted a systematic review and analysis of previous studies in related fields. We found that sample sizes for cancer biomarker screening studies vary widely, depending on the specific biomarker, population, and study design39. Wang et al., in a study similar to our research direction, used 33 samples for training and 508 samples for validation, achieving reliable research results. To enhance the representativeness of our small sample data, we implemented a rigorous standardization process, which mitigates the effects of significant variations in gene expression levels. This standardization ensures that the data is more comparable and reliable. Additionally, we employed a maximum coverage algorithm to screen gene pairs, prioritizing those with higher stability and representativeness within the constraints of our limited sample size. This approach not only reduces the dimensionality of the data and simplifies the model but also enhances its adaptability to small datasets. Specially, we utilized the recently developed “power.fisher.test” function in R to calculate the power of the predictive gene pairs in distinguishing non-responders from responders. The results demonstrated that under current sample size, the statistical power of each predictive gene pair in the final model was all above 99% power. Based on this information and the characteristics and objectives of our study, we determined that our sample sizes—10 pre-treatment responder samples for training and 23 pre-treatment non-responder samples for validation, along with 590 additional samples in independent validation sets—were sufficient for robust biomarker discovery. Once we constructed the prediction model, we validated its performance using independent validation sets that were carefully selected to reflect the broader population we aimed to study. This allowed us to assess the model’s effectiveness in practical applications more accurately. As demonstrated in our results, the predictive model achieved an accuracy of 100% in training dataset and at least 89.47% in validation sets. Collectively, while our REOs framework demonstrates robustness in small cohorts, we acknowledge that very limited samples (e.g., N < 5 per group) may still introduce stochastic bias. Future multi-center studies with standardized protocols will further validate these findings. Nevertheless, our large-scale external validation (N = 590) confirm that the current sample sizes are sufficient for clinical biomarker discovery, particularly given REOs’s inherent resistance to technical variability40.

For the two independent data sets lacking immunotherapy response data, we performed survival and immune infiltration analyses. These analyses revealed significant differences in survival and immune cell infiltration between the predicted responder and non-responder groups, with responders showing higher infiltration levels and immune checkpoint gene expression. These findings further validate the predictive capability of the 15-pair model.

When selecting candidate predictive biomarker gene pairs, we first established a threshold of Pt = 80% for stability to guarantee robustness. While a higher cutoff might theoretically enhance stability, the limited size of our training sample was a crucial consideration, as it may not adequately capture the full range of characteristics present in the population. Then, significantly reversed gene pairs were identified using the Fisher’s exact test. Given the small sample size of the training set, Fisher’s exact test is more suitable than other statistical tests such as the Chi-Squared test. Additionally, for the threshold △Pt used to select reversed gene pairs, we conducted tests with various cutoffs. Our results indicated that as △Pt increased, the number of candidate gene pairs decreased significantly. Specifically, with Pt fixed at 80%, the number of candidate gene pairs decreased dramatically from 320 to 2 when △Pt was increased from 70 to 90% (Supplementary Table S2). This decrease could potentially lead to the loss of valuable gene pairs. Therefore, based on our findings, we concluded that setting Pt at 80% and △Pt at 70% provided a balance between ensuring stability and reversibility of gene pairs while minimizing the risk of losing valuable gene pairs due to the limited size of our training sample.

Pre-treatment samples, which are less impacted by confounding factors than post-treatment samples, accurately reflect a patient’s baseline biological status41. To investigate the impact of including post-treatment samples in our analysis, we combined the GSE91061_pre and GSE91061_on datasets for training purposes. When applying thresholds of Pt = 80% and △Pt = 70%, we observed a reduction in the number of detected gene pairs, with only 140 candidate gene pairs identified. Using a greedy algorithm, we selected 14 of these gene pairs for prediction. Although this model demonstrated accuracy of 100% in the validation sets GSE115821_pre and GSE115821_on, KM survival analysis revealed no significant difference between the two predicted groups in the external datasets GSE22153 and TCGA-SKCM (TCGA-SKCM: p = 0.41, Fig.S3a; GSE22153: p = 0.96, Fig.S3b). These findings indicate that the inclusion of post-treatment data may have introduced noise and confounding factors, likely due to the effects of treatment on gene expression42. In contrast, our previous results demonstrated that the 15-pair model, developed using only pre-treatment samples, effectively stratifies samples without treatment response information into groups with significant survival differences. This highlights the advantage of using these samples helps identify biomarkers that can predict treatment outcomes43. Consequently, based on these findings and the improved performance of the 15-pair model, our study exclusively used pre-treatment samples in its training set. Nonetheless, the potential tradeoffs of excluding post-treatment data deserve careful consideration and further research to fully understand the impact of training data composition on model generalizability and performance.

RECIST 1.1-defined SD has ambiguous therapeutic implications. In our study, we also evaluated 16 pre-treatment samples with SD that were initially excluded from the analysis. The decision to exclude SD samples from the training set was based on their complex biological characteristics. In anti-PD-1 immunotherapy for melanoma, the status of stable SD samples is complex. Their status can change during treatment, potentially transforming into PD or partial/complete response. This uncertainty makes it difficult to predict their outcome accurately, although they are clinically important. The unstable nature of SD samples’ biological characteristics and response patterns can interfere with the model learning process, reducing the model’s ability to capture universal patterns and features, and its predictive accuracy44. For example, by combining SD samples with PD samples to define non-responders, we identified 67 candidate gene pairs with Pt = 80% and △Pt = 70%. Using the greedy algorithm, we selected 11 gene pairs that achieved prediction accuracies of 35.71%, 37.5% and 44.4% across the validation sets GSE91061_on, GSE115821_pre and GSE115821_on, respectively. Notably, merging SD samples with responder samples to define responders resulted in only 16 reversed gene pairs under the same thresholds. Therefore, we chose to exclude SD samples from training. However, recognizing the clinical significance of SD outcomes, we partially analyzed these samples to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the study population. Our analysis revealed that among these SD samples, which are known to exhibit varied responses to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy21, 13 were predicted to be non-responders and three were predicted to be responders. The 13 SD samples identified as non-responders were subsequently compared with the non-responders and responders in the GSE91061_pre dataset. The KM survival analysis showed no significant difference in survival time when compared with the non-responders (p-value = 0.13) but demonstrated a significant difference when compared with responders (p-value = 0.0059, Fig.S4 a-b). Furthermore, differential expression analysis of these 13 SD samples revealed 29 differentially expressed genes compared to non-responders and 483 compared to responders in GSE91061_pre. These genes were enriched in 12 and 338 functional terms correlated with the immune response, respectively, with the top 20 terms detailed in Fig.S4 c-d. These findings align with our predicted outcomes, further confirming the predictive accuracy and validity of the 15-pair model. However, while SD exclusion enhances model interpretability, its real-world predictive value requires prospective validation in SD-enriched cohorts.

Since we were unable to enrich KEGG pathways for the 27 genes in the 15-pair model, we selected the top 500 genes that exhibited strong correlations with these 27 genes for KEGG and GO analysis (Relevance R > 0.6, Pearson correlation test, p < 0.0001). The KEGG analysis45 revealed significant enrichment in pathways related to T cell, B cell and others (Fig.S5a). Specially, SOAT1 in 15-pair was involved in the PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer (Fig.S5b). Emerging evidence supports its role in immune evasion and therapy resistance. The inhibition of SOAT1, which participates in cholesterol metabolism, can enhance the anti-tumor activity of CD8+ T cells, thereby potentiating immune checkpoint blockade46. SOAT1 also plays a role in drug resistance and has been proposed as a target for modulation of BRAFi response in melanoma47. The Gene Ontology analysis also showed a significant enrichment of GO terms such as cellular response to tumor necrosis factor, negative regulation of programmed necrotic cell death, and negative regulation of immune response (Fig.S6). These pathways have potential synergistic effects with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, which works by restoring the anti-tumor activity of T cells through the blockade of the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1.

Additionally, utilizing the UALCAN platform (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html), we assessed the expression data from 104 primary melanoma patients versus 368 metastatic melanoma patients, revealing significant expression differences in 14 genes constituting the 15-pair model (Fig.S7). This analysis suggests a potential role for these genes in metastatic melanoma.

Comparing our 15-pair model to Jiang’s model, which includes various cancer types and treatments, Jiang’s model showed no significant difference, whereas the 15-pair model demonstrated a more significant difference in survival between the two groups. One possible reason for these discrepancies could be the specific feature selection utilized in our 15-pair model, which focuses explicitly on biomarkers associated with anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma. This tailored approach likely enhances its sensitivity in identifying relevant subgroups that respond to treatment. Additionally, the inherent complexity and heterogeneity of cancer responses may mean that broader models, like Jiang’s TIDE, struggle to capture the nuances of individual patient responses to specific therapies. The inclusion of more targeted variables in our model may have led to the observed improvement in predictive performance. Moreover, variations in sample size and patient characteristics across the different models could further contribute to the differences in survival outcomes. These factors collectively underscore the importance of model specificity in the context of personalized cancer therapy. Another potential contributing factor is that the models presented by Wang et al. and Jiang et al. were not retrained using the same datasets as our 15-pair model. This shortcoming can undermine the direct comparability of the models. The performance differences we observed might stem from the composition of the datasets rather than the intrinsic superiority of any particular model.

While our 15-pair model showed superior performance in identifying survival differences among melanoma patients treated with anti-PD-1 therapy, its generalizability to other immunotherapies or cancer types remains a question. To assess this, we utilized the GSE168204 dataset, which included eight melanoma patients undergoing pre- or on-treatment with anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Our model correctly predicted all seven non-responders but failed to identify the single responder sample (Supplementary Table S3). When tested on anti-PD1 treated patients with renal cell carcinoma (GSE67501) or non-small cell lung cancer (GSE126044), predictive accuracy dropped below 50% (Supplementary Table S4), which is comparable to random chance. This confirms that our model’s effectiveness is specific to melanoma, likely attributable to biological distinctions such as melanoma’s higher tumor mutational burden or unique immune microenvironment48. To explore broader applicability, we conducted an exploratory muti-cancer analysis combining melanoma (GSE91061_pre), non-small cell lung cancer (GSE126044), and renal cell carcinoma (GSE67501) datasets as training set. This approach yielded a preliminary 9-gene pair biomarker (Supplementary Table S5) with 100% accuracy, though external validation is required. This suggests our research methodology can be strategically adapted to other cancers—for example, by incorporating cancer specific molecular drivers or immune features—to improve clinical utility. Our findings highlight the necessity of cancer-type-specific models while demonstrating that methodological adaptations (e.g., multi-cancer training) may enable broader applicability. Future work should focus on validating these findings in prospective cohorts and refining models for distinct cancer contexts. Therefore, we highlight the importance of developing predictive models tailored to specific immunotherapy responses and cancer types, as variations in tumor biology and treatment mechanisms across different cancers may significantly impact predictive accuracy.

A natural extension of this work is to determine whether the model can also predict responses to anti-PD-L1 therapy. Given that both anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies aim to restore the body’s anti-tumor immune response by blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway, it is plausible that our model could be adapted for anti-PD-L1 therapy. While our model was validated in anti-PD-1 therapy cohorts, its applicability to anti-PD-L1 therapy (e.g., atezolizumab) warrants further investigation. Key challenges may limit generalizability. First, anti-PD-L1 agents block ligand-receptor interactions within the tumor microenvironment, whereas anti-PD-1 acts on T cells. This could differentially impact immune cell recruitment, cytokine profiles, or compensatory pathways, altering the model’s predictive performance. Second, tumor-intrinsic factors (e.g., PD-L1 expression levels) and extrinsic factors (e.g., stromal cell interactions) may uniquely modulate therapeutic responses in anti-PD-L1 contexts. To address these challenges, we propose the following strategies in the future: to validate the 15-pair model in future independent datasets of anti-PD-L1-treated patients to assess its robustness across therapies.

REOs-based biomarkers have been reported to help improve the accuracy of cancer detection and monitor treatment responses. For example, Yang et al.. have developed a web-based tool named rankDetect, which is also based on the REOs of gene intensity. This tool allows users to upload peripheral blood expression data and receive predictive results indicating whether the samples are associated with cancer or healthy status49. This innovative approach demonstrates the practical application of the REOs-based model in clinical settings, facilitating non-invasive cancer diagnostics. In immunotherapy for melanoma patients, predicting treatment response in advance can also help doctors avoid unnecessary treatment for unresponsive patients, reduce treatment-related side effects and medical costs50. In our study, we emphasize the promise of our REOs-based model in evaluating melanoma patients’ responses to immunotherapy, which could facilitate more targeted and personalized treatment strategies. Bridging the gap between current clinical practices and emerging immunotherapy approaches is crucial, and our model offers clinicians a valuable tool for identifying patient subsets most likely to benefit from specific immunotherapeutic interventions. Furthermore, we intend to validate our model using real-time PCR (RT-PCR) on a separate cohort of melanoma patients, which will be recruited in the future, focusing on the expression of individual mRNAs within the 15-pair model. This validation aims to demonstrate the predictive efficacy of our model and its potential role in guiding treatment decisions. We believe that these efforts will significantly contribute to the ongoing advancements in melanoma immunotherapy and facilitate the translation of our research findings into clinical practice.

Despite the promising results, the limited sample size for training the 15-pair model may lead to potential over fitting. Furthermore, uneven responder and non-responder distributions in training datasets may lead to potential biases, resulting in decreased accuracy of the model in predicting response and non-response groups. In leveraging TCGA/GEO datasets, we further recognize three interrelated bias: selection bias from prioritized inclusion of late-stage melanoma stages with complete treatment records, which may underrepresent early-stage cases; technical bias arising from platform heterogeneity (RNA-seq vs. microarray) that introduces batch effects in cross-dataset comparisons; and reporting bias due to inconsistent immunotherapy regimen documentation across retrospective cohorts, potentially compromising non-responder classification reliability. These limitations collectively highlight the need for caution in generalizing findings and underscore the necessity of larger datasets to ensure ongoing optimization and validation. Future research should aim to establish the utility across diverse patient groups and melanoma stages, facilitating personalized immunotherapy approaches.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE91061, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE115821, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE22153) and in TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/projects/TCGA-SKCM). We have included all necessary code in the manuscript as Supplementary File.

References

Ishida, Y., Agata, Y., Shibahara, K. & Honjo, T. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the Immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 11 (11), 3887–3895. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05481.x (1992).

Topalian, S. L., Drake, C. G. & Pardoll, D. M. Targeting the PD-1/B7-H1(PD-L1) pathway to activate anti-tumor immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 24 (2), 207–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2011.12.009 (2012).

Keir, M. E., Butte, M. J., Freeman, G. J. & Sharpe, A. H. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 26, 677–704. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331 (2008).

Xu-Monette, Z. Y., Zhang, M., Li, J. & Young, K. H. PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade: have we found the key to unleash the antitumor immune response?? Front. Immunol. 81597. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01597 (2017).

Henry, L., Nguyen, N., Asokan, G., Hoh, S. M. & Gandhi, J. PD-1 inhibitors in metastatic colorectal cancer. ANZ J. Surg. 91 (12), E758–E759. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.16878 (2021).

Long, G. V. et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy in resected stage IIB or IIC melanoma (KEYNOTE-716): distant metastasis-free survival results of a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 23 (11), 1378–1388. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00559-9 (2022).

Weber, J. S. et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 16 (4), 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(15)70076-8 (2015).

Brahmer, J. R. et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and Immunologic correlates. J. Clin. Oncol. 28 (19), 3167–3175. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609 (2010).

Hounye, A. H. et al. Evaluation of drug sensitivity, immunological characteristics, and prognosis in melanoma patients using an Endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated signature based on bioinformatics and pan-cancer analysis. J. Mol. Med. 101 (10), 1267–1287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00109-023-02365-w (2023).

Robert, C. et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl. J. Med. 372 (26), 2521–2532. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1503093 (2015).

Carretero-Gonzalez, A. et al. Analysis of response rate with ANTI PD1/PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies in advanced solid tumors: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Oncotarget 9 (9), 8706–8715. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.24283 (2018).

Eikenes, G. et al. Therapeutic and adverse effect of Anti-PD1 immunotherapy in melanoma: A retrospective, Single-Institute study of 222 patients. Cancers 15 (15). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15153966 (2023).

Bertolotto, C. Cutaneous and uveal melanoma: two different cancers in therapeutic needs. C.R. Biol. 344 (3), 219–231. https://doi.org/10.5802/crbiol.63 (2021).

Chattopadhyay, C. et al. Uveal melanoma: from diagnosis to treatment and the science in between. Cancer 122 (15), 2299–2312. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29727 (2016).

Legrand, F. A. et al. Association of high tissue TMB and Atezolizumab efficacy across multiple tumor types. J. Clin. Oncol. 36 (15). https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.12000 (2018).

Maibach, F., Sadozai, H., Seyed Jafari, S. M., Hunger, R. E. & Schenk, M. Tumor-Infiltrating lymphocytes and their prognostic value in cutaneous melanoma. Front. Immunol. 11, 2105. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.02105 (2020).

Qi, L. et al. Critical limitations of prognostic signatures based on risk scores summarized from gene expression levels: a case study for resected stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Brief. Bioinform. 17 (2), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbv064 (2016).

Wang, H. et al. Individual-level analysis of differential expression of genes and pathways for personalized medicine. Bioinf. (Oxford England). 31 (1), 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu522 (2015).

Yang, J. et al. A qualitative transcriptional signature for predicting prognosis and response to bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 19 (7), 1497–1505. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-19-0864 (2020).

Bu, X. et al. A novel qualitative signature based on LncRNA pairs for prognosis prediction in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 22 (1), 95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-022-02507-z (2022).

Riaz, N. et al. Tumor and microenvironment evolution during immunotherapy with nivolumab. Cell 171 (4), 934–949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.028 (2017).

Buchbinder, E. I. & Desai, A. CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways: similarities, differences, and implications of their Inhibition. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 39 (1), 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1097/coc.0000000000000239 (2016).

Willsmore, Z. N. et al. Combined anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 checkpoint Blockade: treatment of melanoma and immune mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Immunol. 51 (3), 544–556. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.202048747 (2021).

Han, X. et al. Role of CXCR3 signaling in response to anti-PD-1 therapy. EBioMedicine 48, 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.08.067 (2019).

Tawbi, H. A. et al. Relatlimab and nivolumab versus nivolumab in untreated advanced melanoma. N Engl. J. Med. 386 (1), 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2109970 (2022).

Nishino, M., Ramaiya, N. H., Hatabu, H. & Hodi, F. S. Monitoring immune-checkpoint Blockade: response evaluation and biomarker development. Nat. Reviews Clin. Oncol. 14 (11), 655–668. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.88 (2017).

Scarpa, M., Marchiori, C., Scarpa, M. & Castagliuolo, I. CD80 expression is upregulated by TP53 activation in human cancer epithelial cells. Oncoimmunology 10 (1), 1907912. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402x.2021.1907912 (2021).

Li, D. Y. & Xiong, X. Z. ICOS(+) Tregs: A functional subset of Tregs in immune diseases. Front. Immunol. 11, 2104. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.02104 (2020).

Ayers, M. et al. IFN-γ-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 Blockade. J. Clin. Investig. 127 (8), 2930–2940. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci91190 (2017).

Bentebibel, S. E. & Diab, A. Cytokines in the treatment of melanoma. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 23 (7), 83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-021-01064-4 (2021).

Hashimoto, K. CD137 as an attractive T cell Co-Stimulatory target in the TNFRSF for Immuno-Oncology drug development. Cancers 13 (10). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13102288 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Identification of potential biomarkers for Anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma by weighted correlation network analysis. Genes 11 (4). https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11040435 (2020).

Fu, J. et al. Large-scale public data reuse to model immunotherapy response and resistance. Genome Med. 12 (1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-020-0721-z (2020).

Zhu, G. et al. ARID1B deficiency leads to impaired DNA damage response and activated cGAS-STING pathway in Non-Small cell lung cancer. J. Cancer 15 (9), 2601–2612. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.91955 (2024).

Huang, Y. et al. A pan-cancer analysis identifies SOAT1 as an immunological and prognostic biomarker. Oncol. Res. 31 (2), 193–205. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2023.027112 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Wang, G. & Wang, M. Identification of KNOP1 as a prognostic marker in hepatocellular carcinoma. Translational cancer Res. 12 (7), 1684–1702. https://doi.org/10.21037/tcr-23-4 (2023).

Wu, F. et al. NUP43 promotes PD-L1/nPD-L1/PD-L1 feedback loop via TM4SF1/JAK/STAT3 pathway in colorectal cancer progression and metastatsis. Cell. Death Discovery 10 (1), 241. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-024-02025-z (2024).

Zhou, X. et al. Knockdown THOC2 suppresses the proliferation and invasion of melanoma. Bioengineered 10 (1), 635–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/21655979.2019.1685727 (2019).

Nakayasu, E. S. et al. Tutorial: best practices and considerations for mass-spectrometry-based protein biomarker discovery and validation. Nat. Protoc. 16 (8), 3737–3760. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-021-00566-6 (2021).

Tian, T. et al. Exploring the influence of pre-analytical variables on gene expression measurements and relative expression orderings in cancer research. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 4489. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88756-0 (2025).

Wang, J. et al. CD74 is associated with inflamed tumor immune microenvironment and predicts responsiveness to PD-1/CTLA-4 bispecific antibody in patients with solid tumors. Cancer Immunol. Immunotherapy: CII 73 (2), 36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-023-03604-2 (2024).

Holder, A. M. et al. Defining clinically useful biomarkers of immune checkpoint inhibitors in solid tumours. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 24 (7), 498–512. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-024-00705-7 (2024).

Gibney, G. T., Weiner, L. M. & Atkins, M. B. Predictive biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 17 (12), e542–e551. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30406-5 (2016).

Seymour, L. et al. iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol. 18 (3), e143–e152. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30074-8 (2017).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D1), D672. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Zhou, X. et al. Increases in 4-Acetaminobutyric Acid Generated by Phosphomevalonate Kinase Suppress CD8(+) T Cell Activation and Allow Tumor Immune Escape. Advanced science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany) 11(43):e2403629. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202403629 (2024).

Vergani, E. et al. Targeting of the lipid metabolism impairs resistance to BRAF kinase inhibitor in melanoma. Front. Cell. Dev. Biology. 10, 927118. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.927118 (2022).

Teixido, C., Castillo, P., Martinez-Vila, C., Arance, A. & Alos, L. Molecular markers and targets in melanoma. Cells 10 (9). https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10092320 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. Platform-independent approach for cancer detection from gene expression profiles of peripheral blood cells. Brief. Bioinform. 21 (3), 1006–1015. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbz027 (2020).

Havel, J. J., Chowell, D. & Chan, T. A. The evolving landscape of biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 19 (3), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-019-0116-x (2019).

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Thousand Talents Program of Jiangxi for High-level talents in innovation and entrepreneurship (No. Jxsq2020101096).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yaru Gao: Writing - review & editing, Writing - original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Data curation. Yue Huo: Methodology, Data curation. Lingli Wang: Software. Jiayi Ruan: Software. Lanzhen Chen: Writing - review and editing. Hongdong Li: Writing - review & editing, Software, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. Guini Hong: Writing - review and editing, Supervision, Formal analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Y., Huo, Y., Wang, L. et al. Relative expression orderings based prediction of treatment response to Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in advanced melanoma. Sci Rep 15, 10235 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94931-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94931-0