Abstract

This paper addresses the industrial demand for precision and efficiency in metal surface defect detection by proposing SLF-YOLO, a lightweight object detection model designed for resource-constrained environments. The key innovations of SLF-YOLO include a novel SC_C2f module with a channel gating mechanism to enhance feature representation and regulate information flow, and a newly designed Light-SSF_Neck structure to improve multi-scale feature fusion and morphological feature extraction. Additionally, an improved FIMetal-IoU loss function is introduced to boost generalization performance, particularly for fine-grained and small-target defects. Experimental results demonstrate that SLF-YOLO achieves a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 80.0% on the NEU-DET dataset, outperforming YOLOv8’s 75.9%. On the AL10-DET dataset, SLF-YOLO achieves a mAP of 86.8%, striking an effective balance between detection accuracy and computational efficiency without increasing model complexity. Compared to other mainstream models, SLF-YOLO demonstrates strong detection accuracy while maintaining a lightweight architecture, making it highly suitable for industrial applications in metal surface defect detection. The source code is available at https://github.com/zacianfans/SLF-YOLO.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In contemporary industrial manufacturing, the surface quality of metallic materials is a crucial determinant that directly affects product performance and durability, highlighting the necessity for efficient identification of metal surface defects. Traditional manual inspection methods are often inefficient and prone to human error, leading to missed or false detections. Such limitations pose significant challenges in maintaining product quality and reliability. For instance, industry standards require defect detection systems to achieve a precision of 0.1 mm or better to ensure product safety, while high-speed production lines demand real-time detection within 100 ms per workpiece. Moreover, the diversity of defect types (e.g., cracks, scratches, and dents) and the vast amount of data (often involving millions of images) further complicate the task. Additionally, in resource-constrained industrial environments, detection models must operate within strict computational limits, such as inference speeds below 10 ms and memory footprints under 100 MB. These quantitative challenges underscore the need for robust, efficient, and lightweight automated detection systems.

Recent advancements in object detection have significantly improved the accuracy and efficiency of defect detection systems. Two-stage detection models, such as R-CNN (Region-based Convolutional Neural Network)1, Fast R-CNN2, Faster R-CNN3 and Mask R-CNN4, rely on region proposal techniques to achieve high accuracy but often suffer from high computational costs. In contrast, one-stage methods like SSD (Single Shot MultiBox Detector)5 and YOLO (You Only Look Once)6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 series, simplify the process by directly predicting bounding boxes and class probabilities, achieving real-time performance. Recently, transformer-based object detection frameworks, such as DETR(Detection Transformer)14, have garnered attention for their ability to leverage self-attention mechanisms and contextual information, thus improving detection accuracy and opening new research directions in the field. However, these methods still face challenges in detecting small targets and handling complex backgrounds, which are critical for metal surface defect detection.

In the domain of metal surface defect detection, researchers have explored various adaptations of mainstream object detection algorithms. For instance, Tang et al.15 enhanced Faster R-CNN with attention mechanisms and multi-scale pooling to improve feature extraction. Fang et al.16 introduced an attention module and Mix-NMS into Cascade R-CNN, boosting feature extraction capabilities. Ren et al.17 proposed lightweight backbone networks like LFEBNet to reduce computational complexity while maintaining performance. Lu et al.18 developed SS-YOLO, integrating MobileNetv3 and D-SimSPPF for efficient steel strip defect detection, achieving significant improvements in mAP and computational efficiency. Additionally, EDDNet19 focused on high-efficiency strip defect detection, while OSA-C320 replaced traditional modules to enhance feature representation. Efforts to optimize one-stage models have also been prominent. Yu et al.21 enhanced YOLOv5 with BottleneckCSP and Depthwise Separable Convolution for fine-grained defect detection. The lightweight Yolo-SPI model22 incorporated PANet-based neck modifications and a feature enhancement module to improve accuracy. Ning et al.23 refined YOLOv8 with pruning and lightweight modules to minimize resource usage. Zhu et al.24 improved YOLOv5s with cross-convolution feature connections and an attention module, significantly boosting small defect detection. The YOLO-MIF model25 leveraged multi-head attention mechanisms for subtle surface defect detection. Transformer-based solutions, such as MedDETR26, integrated spatial attention to recover lost details and improve detection speed. These advancements highlight the rapid evolution of techniques for metal surface defect detection, emphasizing the need for accurate, efficient, and lightweight models capable of addressing real-world industrial challenges.

To address these gaps, we propose SLF-YOLO, a lightweight object detection model specifically designed for metal surface defect detection. Our contributions include:

-

1.

SC_C2f Module: A novel module with a channel gating mechanism to enhance feature representation and regulate information flow.

-

2.

Light-SSF_Neck Structure: A newly designed structure to improve multi-scale feature fusion and morphological feature extraction.

-

3.

FIMetal-IoU Loss Function: A customized loss function to boost generalization performance, particularly for fine-grained and small-target defects.

Therefore, these innovations contribute significantly to industrial applications requiring efficient and precise detection of metal surface defects. The structure of the article is as follows: Section "Related work" reviews related works on activation units, multi-scale fusion networks, lightweight convolution techniques and IoU loss functions. Section Method presents a detailed analysis of the proposed SLF-YOLO network, including its architecture and strategies. Section Experiments evaluates the algorithm on two datasets and showcases the experimental results. Section Conclusion summarizes the article’s findings and conclusions.

Related work

YOLOv8

YOLO is a deep learning-based object detection algorithm that simplifies detection tasks by treating them as regression problems. By dividing images into grid cells and directly predicting detection results, YOLO significantly improves detection efficiency and real-time performance. YOLOv813, developed by Ultralytics, represents a significant evolution in this series, offering high performance and flexibility for a wide range of detection tasks. YOLOv8 consists of three main components: Backbone, Neck and Head, each with comprehensive optimizations compared to previous YOLO versions. In the Backbone component, YOLOv8 integrates the C2f module, which incorporates the ELAN structure from YOLOv712. This design enhances feature extraction and gradient flow while maintaining the model’s lightweight architecture. Additionally, the Backbone incorporates the SPPF module, a feature pooling mechanism that mitigates information loss by aggregating local and global features. In the Neck component, YOLOv8 employs a bi-directional feature pyramid network (BiFPN) and PANet structures, enabling efficient bidirectional information transfer and multi-scale feature fusion. This ensures that features from different scales are effectively integrated, improving the detection of multi-scale objects. The Head component adopts an anchor-free detection paradigm, simplifying the traditional detection pipeline while enhancing detection speed and flexibility, particularly for small object detection tasks. To further enhance model accuracy, YOLOv8 incorporates advanced loss functions for both classification and regression, including DFL27 and CIoU28. For specific tasks, additional techniques such as VFL29 have been utilized to improve accuracy and convergence. These innovations make YOLOv8 a versatile and powerful object detection framework that excels in both performance and efficiency, supporting a broad range of scenarios.

Activation units with gating mechanisms

Activation units are fundamental components of neural networks, enabling models to effectively handle complex data. By applying nonlinear transformations, they enhance the representational power of the network. Common activation functions, such as Sigmoid, Tanh and ReLU, are widely used. However, in deep networks and high-dimensional data processing, traditional activation functions often introduce redundant computations and struggle to manage key features effectively. Gating mechanisms address this limitation by dynamically generating gating signals to adaptively control feature channels. These mechanisms optimize the flow of information, highlight critical features and suppress irrelevant ones. A notable example is the Gated Linear Unit (GLU)30, which uses the Sigmoid function to produce gating signals for element-wise gating. Originally introduced for natural language processing tasks, GLU splits inputs into feature and gate components, enabling efficient information control. An extended variant, the Channel-wise Gated Linear Unit (CGLU)31, applies gating at the channel level, making it particularly suited for multimodal tasks and image processing. Similarly, in recurrent neural networks, mechanisms like the Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)32 and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)33 employ gates, such as update and forget gates, to efficiently model long sequences and maintain temporal dependencies. Activation units with gating mechanisms not only enhance the nonlinear expressive power of models but also reduce computational overhead, improving resource utilization efficiency. This makes them powerful tools for advancing the capabilities of modern neural networks across various applications.

Multi-scale fusion networks

Multi-scale fusion networks play a pivotal role in deep learning by integrating features from various levels to enhance performance in tasks such as object detection and semantic segmentation. Convolutional neural networks extract features of varying scales at different levels: higher-level features focus on semantic information, while lower-level features retain spatial details and geometric structures. Fusion networks address the limitations of single-level information, enabling models to capture both global and local features effectively. Several multi-scale fusion architectures have been developed to tackle these challenges. Feature Pyramid Network (FPN)34 enhances feature integration across different scales using a pyramidal structure, balancing features from high and low levels. Path Aggregation Network (PANet)35 introduces path augmentation mechanisms to shorten information propagation paths, while Bi-directional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN)36 improves efficiency with bidirectional cross-layer connections and normalized fusion strategies. These architectures effectively integrate multi-scale information, optimizing detection tasks. Innovative approaches, such as the ScaleSeq Network37, further advance multi-scale fusion by proposing sequential feature fusion and skip connections. By employing 3D convolutions and adaptive weight allocation strategies, ScaleSeq improves information transmission paths, enhances the detection of small objects and reduces background interference. Additionally, it effectively addresses the gradient vanishing problem common in deep networks. These advancements demonstrate the critical role of multi-scale fusion in achieving robust and efficient deep learning models, making it indispensable for addressing advanced and multifaceted visual tasks.

Lightweight convolution techniques

With the rapid development of deep learning, detectors based on neural networks have been widely applied in the field of object detection. However, deep neural networks often involve a large number of parameters and require high computational demands, posing significant challenges in resource-constrained environments such as mobile devices and embedded systems. To address these limitations, lightweight convolution techniques have become a critical research focus, aiming to reduce computational complexity while meeting the demands of resource-constrained applications. Depthwise Separable Convolutions (DSC) are among the most widely used lightweight methods. By decomposing Standard Convolution (SC) into depthwise convolution (applied to each channel separately) and pointwise convolution (\(1 \times 1\) convolution), DSC significantly reduces floating-point operations and parameter counts. However, this decomposition can lead to a slight reduction in feature representation capability due to the separation of channel information. To overcome this limitation, Group Convolutions divide input channels into multiple independent groups, enabling efficient convolution operations while reducing computational costs. This technique has been widely adopted by models like ResNeXt38. Building on the concept of group convolutions, Shuffled Convolutions introduce a “channel shuffle” mechanism to enhance information exchange between different groups, further improving the model’s representational capacity while maintaining a low computational overhead. Lightweight convolution techniques are widely used in mobile devices and real-time applications, providing critical support for deploying deep learning models in resource-limited settings. They represent a key step forward in making advanced deep learning architectures accessible across various practical scenarios.

IoU loss functions

The Intersection over Union (IoU) loss function is a crucial metric in object detection, measuring the overlap between predicted and ground truth bounding boxes. Traditional IoU loss evaluates the localization accuracy by calculating the ratio of the intersection area to the union area. However, when the predicted and ground truth boxes do not overlap, the gradient becomes zero, providing no effective learning signal. To address this limitation, several improved IoU loss functions have been proposed to enhance the accuracy and stability of bounding box regression. Generalized IoU (GIoU)39 extends the traditional IoU by incorporating the smallest enclosing rectangle of the predicted and ground truth boxes. Even when there is no overlap, GIoU provides an optimization direction, improving convergence. Building on GIoU, Distance IoU (DIoU)28 introduces the Euclidean distance between the center points of the predicted and ground truth boxes, which accelerates convergence during training. Complete IoU (CIoU)28 further improves IoU by adding a constraint on aspect ratio consistency, ensuring that the predicted box not only aligns in position but also matches the scale and shape of the ground truth box. Efficient IoU (EIoU)40 directly minimizes the normalized differences in width, height and center position between the predicted and ground truth boxes, resulting in enhanced regression performance. Skew IoU (SIoU)41 modifies standard IoU to account for orientation differences between the predicted and ground truth boxes. This adjustment optimizes bounding box regression, especially in scenarios with rotated or skewed objects. These advanced IoU loss functions significantly improve the precision and stability of bounding box regression in complex scenarios. They enhance the robustness and generalization capabilities of YOLO models, providing reliable technical support for better performance in object detection tasks.

Method

SLF-YOLO model

Fig. 1 illustrates the YOLOv8 model architecture for a clearer comparison with our model structure. SLF-YOLO is an enhanced lightweight object detection model specifically designed for efficient detection in resource-constrained environments, such as mobile devices. The framework integrates several key improvements to achieve high performance with minimal computational requirements. An overview of the model architecture is provided in Fig. 2. In the backbone network, the SC_C2f module replaces YOLOv8’s C2f structure. This modification incorporates the Bottleneck Block and SC Block, along with the addition of the CGLU activation mechanism to adaptively regulate feature flow. These enhancements improve feature representation, nonlinear expressiveness and adaptability to complex inputs, while maintaining computational efficiency. Within the neck, the GSConv module combines SC with DSC, leveraging rich information from convolutional layers while reducing computational costs. This ensures improved feature extraction under constrained conditions. The model further adopts the VoVGSCSP_1 structure, which optimizes the feature extraction process through cross-layer sharing and reduces the computational burden. The Scale-Sequence Fusion (SSF) module enhances the model’s multi-scale object detection capabilities by integrating features across different scales, significantly benefiting small-object detection in various scenarios. To further improve detection performance, SLF-YOLO introduces an enhanced loss function by integrating concepts from FocalIoU-Loss and Inner-IoU. This novel approach improves localization precision, accelerates convergence and ensures robust detection of targets across scales. These improvements make SLF-YOLO particularly effective for detecting small defects and handling complex scenarios. By combining these innovations, SLF-YOLO delivers significant improvements in detection speed and accuracy, making it well-suited for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

SC_C2f block

To address challenges such as insufficient feature representation, loss of convolutional features, reduced computational efficiency and gradient vanishing in deep networks caused by limited channel numbers and network depth in lightweight object detection networks, this study draws inspiration from existing works42,43 and proposes a novel SC_C2f module, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The SC_C2f module is designed to enhance feature fusion and nonlinear expression by leveraging the Star Block. The Star Block achieves efficient feature integration through star operation-based computations. Features are hierarchically combined along the channel dimension in the input of the Star Block, followed by two linear transformations and element-wise multiplication to achieve low-rank dimensional expansion. This approach ensures improved feature representation while maintaining computational efficiency. The specific formulation is:

Here, \(W_1\) and \(W_2\) are learnable linear transformation matrices, and \(\odot\) denotes element-wise multiplication, facilitating complex nonlinear interactions between different channels. To enhance precision and stability, the Star Block employs residual connections, directly transmitting input features to the output, thereby improving the robustness of feature representation.

The design incorporates the CGLU activation unit and residual structure to enhance feature expression capability with low computational overhead, effectively addressing channel selection in network design. Within the SC Block, the CGLU is dynamically added to the end of the Star Block to achieve channel-level dynamic feature control. CGLU performs dynamic feature selection by controlling the activation mechanism, splitting the input features into \(X_1\) and \(X_2\), mapping them into weights through a Sigmoid activation, and then performing element-wise multiplication with \(X_1\). The specific formulation is:

Here, \(\sigma (\cdot )\) represents the Sigmoid activation function. CGLU dynamically adjusts the activation state of channels, highlighting key features and suppressing redundant information. By splitting the output of the Star Block along the channel dimension, the generated gated weights are element-wise multiplied with another part, thereby achieving channel selection. This improves feature selectivity while maintaining high computational efficiency, endowing the model with stronger nonlinear expression capabilities.

The SC Block, which integrates the lightweight characteristics of the Star Block and the dynamic gating mechanism of CGLU, significantly enhances feature extraction capabilities while enabling structural adaptability. This allows the network to self-regulate based on input feature information, improving its ability to handle complex cross-transformations. Moreover, the combination of residual connection and CGLU effectively mitigates the gradient vanishing problem, ensuring stable training convergence. This design strikes an excellent balance between feature representation capability and computational cost, enhancing inference efficiency and making it highly suitable for lightweight object detection tasks.

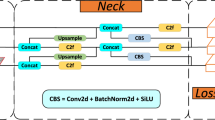

Light-SSF_Neck

This study draws inspiration from existing research37,44 to propose a novel Neck structure, Light-SSF_Neck, designed to achieve lightweight design, efficient feature fusion and multi-scale detection integration. This structure significantly reduces computational overhead, enhances feature representation accuracy and facilitates multi-scale feature interaction, providing robust support for lightweight detection models in practical applications. The specific architecture is illustrated in Fig. 4. Retaining the core structure of FPN-PANet, Light-SSF_Neck introduces the SSF module for initial feature fusion, enabling a lightweight and efficient feature integration process through a modular design. The GSConv module combines SC with DSC to significantly reduce computational complexity. The VoVGSCSP module optimizes the reuse and transmission of multi-scale features through cross-layer sharing, further enhancing feature expressiveness. Additionally, the SSF module improves multi-scale feature integration, excelling in small object detection tasks. Through a bidirectional feature fusion pathway, Light-SSF_Neck effectively balances detection performance and computational efficiency, making it highly suitable for real-time object detection in complex scenarios and resource-constrained environments. The three innovative modules comprising this structure are detailed in the following sections.

GSConv

GSConv is a lightweight convolution module designed to combine the strengths of SC and DSC, achieving a balance between computational efficiency and feature representation capability. The structures of SC and DSC are illustrated in Fig. 5. Using a parallel structure, GSConv divides the input features into two distinct paths, where SC and DSC are applied separately. This design effectively enhances inter-channel information interaction, as shown in Fig. 6. For a given input feature \(\mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C_\text {in}}\), the SC operation is defined as follows:

Here, \(W_{\text {sc}} \in \mathbb {R}^{K \times K \times C_\text {in} \times C_\text {out}/2}\) is the SC kernel, and the output feature size is \(\mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C_\text {out}/2}\). DSC processes the input features in two steps: depthwise convolution followed by point-wise convolution, as shown below:

Here, \(W_{\text {DSC-d}} \in \mathbb {R}^{K \times K \times 1 \times C_\text {in}}\) is the depthwise convolution kernel, and \(W_{\text {DSC-p}} \in \mathbb {R}^{1 \times 1 \times C_\text {in} \times C_\text {out}/2}\) is the pointwise convolution kernel. The output features from the two branches are concatenated and then fused through channel shuffling:

This fusion strategy enhances feature expression capability while reducing computational complexity. Compared to traditional convolution, GSConv significantly decreases computational overhead. The computational cost per layer is calculated as follows:

GSConv maintains a high level of feature representation capability while significantly reducing computational load and parameter usage. The shuffling operation facilitates efficient information exchange between features, addressing the limitations of DSC in channel information fusion. This approach brings the feature expression capability of GSConv closer to that of SC. Additionally, the design of GSConv, which first propagates features and then fuses them, further improves inference time and reduces resource consumption, making it particularly suitable for lightweight object detection tasks. When integrated into the Neck component of YOLOv8, the module significantly enhances multi-scale feature fusion efficiency. This ensures an optimal balance between complex multi-scale detection performance and computational efficiency, providing robust technical support for constructing efficient lightweight detection networks.

VOVGSCSP

Building upon GSConv, this study introduces the GS Bottleneck structure and integrates a one-shot aggregation strategy to design a Cross-Stage Partial (CSP) module, termed VoVGSCSP. The aim is to enhance feature representation capability and computational efficiency in Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). VoVGSCSP integrates the CSP and VoVNet modules, achieving a substantial reduction in computational complexity and inference time while maintaining high accuracy. This is accomplished through cross-stage feature sharing and parallel convolution operations, as illustrated in Fig. 7.

The core of VoVGSCSP lies in the feature reuse of the CSP module and the efficient convolution of VoVNet, further optimized by GSConv to enhance computational performance and reduce redundancy. The module divides the input feature X into multiple paths, enabling information sharing and fusion, thereby improving the model’s learning capability and inference efficiency. To further reduce model complexity, this study employs a lightweight version, VoVGSCSP_1. The computational flow of VoVGSCSP is based on branching and fusion strategies for input features, balancing feature representation capability and computational efficiency. Initially, the input feature \(X \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C_{in}}\) is split into two parts, \(X_1\) and \(X_2\), which are processed through different paths. In the main path, \(X_1\) is processed by the GS Bottleneck module to capture rich high-level semantic features. The computation can be expressed as:

Meanwhile, the feature \(X_2\) is processed in the auxiliary path using a SC kernel to retain part of the input features and reduce redundant computations. This is represented as:

Subsequently, the outputs \(Y_1\) and \(Y_2\) from the two paths are fused through concatenation, followed by a \(1 \times 1\) convolution to compress the number of channels, resulting in the final output:

VoVGSCSP leverages the strengths of CSP and VoVNet by maximizing feature reuse through feature branching and cross-path sharing, effectively reducing redundant computations and enhancing information exchange between networks. The integration of efficient convolution via GSConv further decreases the number of parameters and computational load, ensuring an optimal balance between performance and resource efficiency. Additionally, the channel-shuffling mechanism facilitates effective information exchange between channels, addressing the limitations of DSC in channel information fusion and improving model stability in complex scenarios. Compared to traditional convolutional networks, VoVGSCSP significantly reduces inference time while maintaining high accuracy, making it highly suitable for real-time object detection tasks.

Scale sequence fusion

The SSF module is an innovative design for multi-scale feature fusion, aimed at enhancing the model’s ability to detect targets of varying scales and ensuring efficient and accurate detection in complex scenarios. The structure of this module is illustrated in Fig. 8. SSF extracts features from three levels of the backbone network (P3, P4 and P5) and achieves feature alignment and fusion through convolution, upsampling and concatenation operations, enabling efficient interaction at the same scale. Initially, the features extracted from P3, P4 and P5 are processed through CBS modules, which combine Convolution, Batch Normalization and SiLU activation functions. This enhances the expressive capability of each layer’s features, denoted as:

These features are then aligned through layer-wise upsampling and concatenation. Specifically, the features from P5 are upsampled to match the spatial dimensions of P4, and subsequently, the features from P4 are further upsampled to match those of P3. This ensures that all features are fused at the same scale. The specific computations are represented as:

After upsampling, the feature maps are concatenated with the features from the P3 layer along the channel dimension and further processed through a 3D convolution to capture the complex contextual information among multi-scale features:

Subsequently, the fused features are further optimized through max pooling and channel compression operations to reduce redundant information and enhance computational efficiency:

The modular design of the SSF module ensures effective interaction between fine-grained layer information and deep global semantic information. The integration of 3D convolution not only strengthens the connections between different scales but also enhances the model’s adaptability to variations in target size and orientation. This multi-scale fusion strategy reduces information loss while minimizing computational complexity, thereby supporting the inference process of subsequent detection heads and achieving an optimal balance between detection accuracy and inference speed.

FIMetal-IoU

To enhance optimization performance across various sample types, this paper proposes an IoU loss function specifically designed for metal surface defect detection, termed FIMetal-IoU. This loss function achieves efficient optimization through adaptive weighting and differentiated processing. Drawing inspiration from existing works45,46, FIMetal-IoU not only focuses on the internal coverage of bounding boxes but also dynamically adjusts loss weights based on the depth of the bounding boxes. This approach enhances the model’s ability to recognize complex scenes and detect hard-to-identify targets effectively.

Firstly, \(\text {IoU}^{Inner}\) introduces an auxiliary bounding box mechanism to extend the applicability of the IoU loss, enabling more precise handling of samples with high and low IoU, as illustrated in Fig. 9. Specifically, the auxiliary bounding boxes are adjusted in size by setting a scaling factor ratio within the range [0.5, 1.5]. The boundary coordinates of the auxiliary bounding box for the ground truth are calculated as:

The boundary coordinates of the auxiliary bounding box for the predicted box are calculated as:

Here, \(x_{\text {gt}}\) and \(y_{\text {gt}}\) denote the center coordinates of the ground truth bounding box, while \(w_{\text {gt}}\) and \(h_{\text {gt}}\) represent the width and height of the ground truth bounding box. Similarly, \(x_{\text {c}}\) and \(y_{\text {c}}\) are the center coordinates of the predicted bounding box, and w and h are the width and height of the predicted bounding box. The overlapping area and the union area of the auxiliary bounding boxes are calculated as follows:

Finally, the calculation formula for \(\text {IoU}^{Inner}\) is:

On top of this, \(\text {IoU}^{Inner}\) is integrated with \(\text {IoU}^{Focaler}\) to form a new IoU loss function. According to the piecewise interval mapping strategy of \(\text {IoU}^{Focaler}\), the new loss function is divided into three intervals, where \([d, u] \subset [0, 1]\). When \(\text {IoU}^{Inner}\) is below the lower bound parameter d, its loss is set to 0 to ignore the interference from invalid samples. In the moderate IoU interval (i.e. \(d \ll \text {IoU}^{Inner} \ll u\)), \(\text {IoU}^{Inner}\) is linearly mapped to the [0, 1] interval with the following computation:

This linear mapping significantly increases the gradient weight within the moderate IoU interval, enhancing the model’s focus on difficult samples within this range. For high IoU samples (i.e. \(\text {IoU}^{Inner} > u\)), the loss is mapped to 1, thereby reducing the loss weight for well-localized samples. Combining the aforementioned piecewise handling, the newly defined IoU loss function is expressed as:

The final loss is defined as \(L_{{FIMetal-IoU}} = 1 - \left( FIMetal-IoU\right)\). FIMetal-IoU is a specialized IoU loss function designed to improve metal defect detection, particularly for challenging cases such as small, complex, or partially occluded defects like cracks and dents. It incorporates three key innovations: an auxiliary bounding box mechanism to ensure gradient signals even without overlap, dynamic weight adjustment to prioritize difficult samples and reduce background interference, and a piecewise mapping strategy to optimize learning based on IoU intervals. These features enhance sensitivity to small objects and edge targets, minimizing false positives and missed detections, while improving overall accuracy and robustness, especially in scenarios with class imbalance or complex defect shapes.

Experiments

Datasets and experimental environment

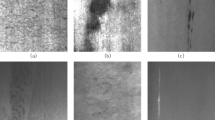

The NEU-DET dataset47, released by Northeastern University, is a standard benchmark widely used for steel surface defect detection and machine learning research. It includes six common defect types: Crazing (Cr), Patches (Pa), Inclusion (In), Pitted Surface (PS), Rolled-in Scale (RS) and Scratches (Sc). Each defect category consists of 300 grayscale images with a resolution of \(200 \times 200\) pixels. The dataset is divided into training, validation and testing sets in an 8:1:1 ratio, with the category distribution illustrated in Fig. 10(a).

The AL10-DET dataset48, provided by the Alibaba Cloud Tianchi platform, is specifically designed for aluminum surface defect detection. It contains over 10,000 high-resolution images (\(2560 \times 1920\) pixels) covering ten defect types, including Leaky-Bottom (LB), Non-Conductivity (NC), Orange-Peel (OP), Scratch (Sc), Dirty-Spots (DP), Variegated-Color (VC), Paint-Bubble (PB), Jet-Stream (JS), Pitting (Pi) and Corner-Leaky-Bottom (CLB). For this study, approximately 3,700 images were selected and annotated. To improve the model’s generalization ability, we applied extensive data augmentation techniques, including random rotation (\(\pm 10^\circ\)), random scaling (0.9 to 1.1 times), random cropping, weather simulations (rain and fog) and noise addition (Gaussian and salt-and-pepper noise), expanding the dataset to around 4,650 images. These augmentations help the model better handle real-world variations and improve its robustness in diverse industrial scenarios. This augmented dataset, referred to as AL10-DET, was similarly divided into training, validation and testing sets in an 8:1:1 ratio, with the category distribution shown in Fig. 10(b).

The experiments were conducted using PyTorch 2.2.2 as the deep learning framework to ensure efficient and flexible model development. Training was accelerated using an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU with CUDA 11.8 and cuDNN 7.0, optimizing both training speed and performance. The development environment was based on Python 3.10.14, with dependencies managed via pip to ensure consistency across implementations. To improve the model’s detection capability across scales, particularly for small objects, the input sizes were adaptively adjusted to \(640 \times 640\) pixels, significantly optimizing model performance. And Table 1 illustrates some experimental details of each framework.

Evaluation metrics

To evaluate the detection performance of the model, this study employs multiple metrics, including mAP, Precision (P), Recall (R), FLOPs and Params. R reflects the model’s ability to identify positive samples accurately. It is calculated as follows:

Here, TP represents the number of correctly detected positive samples, and FN represents the number of missed positive samples.

P evaluates the reliability of the model’s predictions and is calculated as follows:

Here, FP represents the number of negative samples incorrectly classified as positive. Average Precision (AP) quantifies the detection performance for a single class by calculating the area under the Precision-Recall (P-R) curve. The mAP metric averages the AP values across all classes to measure the overall performance of multi-class detection. The calculations are as follows:

Here, p(k) represents the precision at the k-th position, \(\Delta R(k)\) is the change in recall at position k, and C is the total number of classes. AP is the average precision for a specific class. These metrics balance precision and recall while using mAP to provide an overall evaluation, making them effective for assessing the accuracy and robustness of the model across multi-class scenarios.

FLOPs measure the computational complexity of the model, indicating the number of floating-point operations required for a single forward pass. For a convolutional layer, FLOPs can be calculated as:

Where \(H\) and \(W\) are the height and width of the output feature map, \(C_{\text {in}}\) is the number of input channels, \(C_{\text {out}}\) is the number of output channels, and \(K_h\) and \(K_w\) are the height and width of the convolutional kernel. Lower FLOPs values generally indicate higher computational efficiency.

Params represent the total number of trainable parameters in the model. For a convolutional layer, Params can be calculated as:

Where \(C_{\text {in}} \times C_{\text {out}} \times K_h \times K_w\) represents the parameters of the convolutional kernel, and \(C_{\text {out}}\) represents the bias terms. A lower number of parameters typically indicates a more lightweight model, which is advantageous for deployment in resource-constrained environments. By combining these metrics, we comprehensively evaluate the model’s detection accuracy, computational efficiency and suitability for practical applications.

Selection of the baseline model

In this study, we selected YOLOv8 as the baseline model primarily due to its exceptional performance across various applications, especially in metal surface defect detection. YOLOv8 effectively balances detection accuracy and computational efficiency, which is crucial for meeting the real-time demands of industrial inspections. To further enhance the model’s computational efficiency and detection accuracy, we conducted an experimental comparison between two lightweight variants of YOLOv8 and ultimately chose YOLOv8s as our baseline model.

In selecting YOLOv8s, we compared its performance with YOLOv8n on the NEU-DET and AL10-DET datasets, as summarized in Table 2. The experimental results indicate that, although YOLOv8n has a lower parameter count and computational cost, YOLOv8s demonstrates superior performance in terms of recall and mAP. Notably, YOLOv8s shows a clear advantage in detection accuracy. Specifically, on the NEU-DET dataset, YOLOv8n slightly outperforms YOLOv8s in mAP50 (76.6% vs. 75.9%), but YOLOv8s achieves a higher recall (71.8% vs. 71.2%), which means it is more reliable in detecting positive samples, particularly in identifying small defects on metal surfaces. Moreover, YOLOv8s outperforms YOLOv8n across all key metrics on the AL10-DET dataset, including precision, recall, mAP50 and mAP50:95.

Based on these experimental findings, despite YOLOv8n being more lightweight in terms of computational resources, YOLOv8s offers a better overall balance, particularly in terms of detection accuracy and recall. Given the high precision requirements for metal surface defect detection, YOLOv8s was ultimately chosen as the baseline model for its robust performance and efficiency across the datasets.

Ablation study

To evaluate the individual contributions of each module and their combined effects, a series of comprehensive ablation experiments were conducted on the NEU-DET and AL10-DET datasets. These studies aimed to analyze the impact of the SC_C2f module, the Light-SSF_Neck structure, and the improved FIMetal-IoU loss function on the overall performance of the proposed SLF-YOLO. Table 3 summarizes the experimental design, and the category-specific AP results, shown in Table 4 and Table 5, further demonstrate the robustness of the SLF-YOLO.On both the NEU-DET and AL10-DET datasets, the SC_C2f module and other proposed components significantly enhanced detection performance across challenging categories, with the complete SLF-YOLO achieving the highest AP values, including 97.1% for “Scratches” and 65.1% for “Paint-Bubble”.

Regarding overall evaluation metrics (Table 6 and Table 7), the SLF-YOLO demonstrated substantial improvements in both datasets while maintaining computational efficiency. On the NEU-DET dataset, incorporating the SC_C2f module (Model A) led to a mAP50 of 78.1%, compared to the baseline model’s 75.9%. Adding the Light-SSF-Neck structure (Model B) resulted in a mAP50 of 77.6%, highlighting its effectiveness in multi-scale feature fusion and improving detection accuracy for objects of varying sizes. The inclusion of the FIMetal-IoU loss function (Model C) further enhanced bounding box regression precision, particularly for small-object detection, achieving a mAP50 of 77.4%. Combining these modules revealed their synergistic effects: Model D, integrating the SC_C2f module and Light-SSF_Neck structure, achieved a mAP50 of 79.3%, while Model E, combining the SC_C2f module and the FIMetal-IoU loss function, reached 78.5%. Model F, integrating the Light-SSF_Neck structure and the FIMetal-IoU loss function, achieved a mAP50 of 78.5%, demonstrating the complementary benefits of these two components. The SLF-YOLO outperformed all others, achieving a mAP50 of 80.0% and improving P and R to 75.9% and 76.1%, respectively. Additionally, mAP50:95 improved from 41.1% to 49.0%, while computational cost was reduced, with parameters dropping to 9.65M and FLOPs decreasing to 24.6G compared to YOLOv8s’ 11.12M parameters and 28.4G FLOPs.

On the AL10-DET dataset, the baseline model’s mAP50 of 83.0% was significantly improved through the integration of the proposed modules. Model A, incorporating the SC_C2f module, achieved a mAP50 of 84.3%, while Model B, featuring the Light-SSF_Neck structure, reached 84.9%. Adding the FIMetal-IoU loss function in Model C further improved performance to 85.2%. When modules were combined, performance gains were even more pronounced. Model D achieved a mAP50 of 85.6%, followed by Model E, which attained a mAP50 of 86.4%. Model F, integrating the Light-SSF Neck structure and the FIMetal-IoU loss function, reached a mAP50 of 85.5%. Ultimately, the SLF-YOLO model demonstrated superior performance, securing the highest mAP50 of 86.8%. These results validate the efficiency and effectiveness of the proposed modules in improving detection performance, particularly for small objects and challenging categories, while significantly reducing computational overhead.

In summary, the ablation experiments highlight the critical contributions of the SC_C2f module, the Light-SSF_Neck structure, and the FIMetal-IoU loss function. Each component independently enhances feature extraction, multi-scale fusion, and regression accuracy, while their integration delivers substantial synergistic improvements.

Comparative analysis with other models

Table 8 and Table 9 present the comparative results of the SLF-YOLO against several representative methods-SSD, Faster-RCNN, RTDETR, YOLOv3-tiny, YOLOv4, YOLOv5s, YOLOv6s and YOLOv7-on the NEU-DET and AL10-DET datasets, using consistent experimental settings and environments. Similarly, Table 10 and Table 11 show the comparison of other evaluation metrics. The visualization results are shown in Fig. 11 and Fig. 12.

On the NEU-DET dataset, SLF-YOLO achieved the highest mAP50 of 80.0% and mAP50:95 of 49.0%, significantly outperforming YOLOv8s, which reached only 75.9% and 41.1%, respectively. SLF-YOLO also delivered exceptional results across individual categories. For example, the AP for “Scratches” achieved an outstanding 97.1%, surpassing all baseline models. In other challenging categories such as “Rolled-in Scale” and “Crazing,” SLF-YOLO demonstrated superior performance, achieving AP values of 69.6% and 47.6%, respectively, indicating its robustness in detecting diverse defect types. Similarly, on the AL10-DET dataset, SLF-YOLO reached an mAP50 of 86.8% and an mAP50:95 of 68.9%, outperforming YOLOv8s, which achieved 83.0% and 65.3%, respectively. Specific improvements were noted in categories such as “Leaky-Bottom” and “Jet-Stream,” where SLF-YOLO achieved AP values of 98.9% and 92.2%, respectively.

In terms of overall evaluation metrics, SLF-YOLO demonstrated a remarkable balance between detection accuracy and computational efficiency. On the NEU-DET dataset, SLF-YOLO achieved a P of 75.9% and R of 76.1%, outperforming RTDETR, which achieved 67.4% Precision and 62.5% Recall. Additionally, SLF-YOLO exhibited a significantly lower parameter count of 9.65M and FLOPs of 24.6G compared to RTDETR’s 41.9M parameters and 125.6G FLOPs, showcasing its lightweight design and suitability for resource-constrained applications. Similarly, on the AL10-DET dataset, SLF-YOLO maintained superior performance with a P of 85.7% and R of 81.4%. Compared to other models, SLF-YOLO consistently outperformed YOLOv3-tiny and YOLOv5s in both datasets. For instance, YOLOv5s achieved an mAP50 of 74.7% and an mAP50:95 of 41.7% on the NEU-DET dataset. Furthermore, compared to the two-stage model RTDETR, SLF-YOLO demonstrated clear advantages in both accuracy and computational efficiency. While RTDETR achieved an mAP50 of 64.0% on the NEU-DET dataset, it required 125.6G FLOPs, making it unsuitable for lightweight deployment. In contrast, SLF-YOLO’s lightweight design and reduced computational complexity make it ideal for real-time detection tasks in industrial applications.

The comparative analysis highlights SLF-YOLO’s superior accuracy, robustness, and efficiency across diverse defect types and challenging scenarios, validating its practicality for high-precision detection with limited computational resources.

In this research, we meticulously evaluated the performance of YOLOv949, YOLOv1050, and YOLOv1151, benchmarking them against the foundational model YOLOv8s and the advanced SLF-YOLO model. YOLOv8s was selected as the baseline due to its significant enhancements in performance within the YOLO series, offering a stable and efficient standard for gauging advancements in newer iterations. Each subsequent model-YOLOv9, YOLOv10, and YOLOv11-incorporated specific technological improvements built on this baseline. These enhancements included optimized feature fusion mechanisms, expanded network architectures, and novel attention mechanisms, all tailored to enhance detection capabilities in targeted scenarios. Experimental assessments on the NEU-DET and AL10-DET datasets yielded insightful outcomes. Table 12 lists the specific experimental results. YOLOv9s recorded a mean Average Precision of 74.9% on NEU-DET and 82.0% on AL10-DET, showcasing robust detection capabilities for medium to large-sized targets. YOLOv10s demonstrated an mAP of 72.5% on NEU-DET and 81.1% on AL10-DET, emphasizing its advantages in processing speed and streamlined architecture. Meanwhile, YOLOv11s achieved an mAP of 75.2% on NEU-DET and 83.3% on AL10-DET, underscoring its exceptional performance in complex environments. These findings not only reaffirm the appropriateness of selecting YOLOv8s as the baseline model but also distinctly highlight the superior technological prowess of SLF-YOLO in metal surface defect detection within the object detection domain.

Conclusion

This study introduces SLF-YOLO, an improved YOLO-based model for accurate and efficient metal surface defect detection. Built upon YOLOv8, SLF-YOLO incorporates several key optimizations, including the SC_C2f module and the Light-SSF_Neck structure, to strengthen multi-scale feature fusion capabilities. Additionally, the improved FIMetal-IoU loss function is introduced to boost precision, particularly in small object detection tasks.Experimental results demonstrate that SLF-YOLO achieves mAP50 and mAP50:95 scores of 80.0% and 49% on the NEU-DET dataset and 86.8% and 68.9% on the AL10-DET dataset, significantly outperforming comparative models. These results validate the effectiveness of its enhancements in multi-scale feature fusion and bounding box regression, meeting the demands of high-precision detection. SLF-YOLO leverages lightweight convolution modules and channel shuffle mechanisms, maintaining low computational costs while achieving excellent feature representation capabilities. With outstanding performance in terms of parameters and FLOPs, SLF-YOLO is well-suited for real-time detection scenarios, surpassing traditional YOLO models in efficiency and precision. It demonstrates a robust balance between detection accuracy and inference speed, offering an efficient and reliable solution for surface defect detection in steel and other industrial applications. These findings provide valuable insights for industrial defect detection technologies. The generalizability and practicality of the SLF-YOLO make it highly applicable in fields such as autonomous driving, video surveillance and industrial inspection. Future research will focus on further optimizing the model’s architecture and exploring its application in more real-world scenarios, particularly in small object detection and complex background conditions, to advance the development of industrial inspection technologies.

Despite its strong performance in metal surface defect detection, SLF-YOLO has several limitations. First, the model’s performance is highly dependent on the quality and diversity of the training data, and class imbalance may lead to suboptimal detection for certain defect categories. Second, there is room for improvement in detecting extremely small targets (e.g., pixel-level defects) and handling complex backgrounds. Additionally, although SLF-YOLO is designed as a lightweight model, its inference speed and memory footprint may still pose challenges in highly resource-constrained environments. Future work will focus on enhancing the model’s robustness and efficiency through advanced data augmentation, optimized multi-scale feature fusion, the integration of attention mechanisms and model compression techniques such as pruning and quantization, aiming to address more complex industrial scenarios.

Data availability

The datasets can be accessed at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/arcanine9/net-det and https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/arcanine9/al10-det.

References

Girshick, R., Donahue, J., Darrell, T. & Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation, in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition , pp. 580–587. (2014) https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2014.81

Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN, in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision , pp. 1440–1448. (2015) https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2015.169

Ren, S., He, K., Girshick, R. & Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 39(6), 1137–1149. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031 (2017).

He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollár, P. & Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 42(2), 386–397. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2844175 (2020).

Liu, W., et al. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector, in European Conference on Computer Vision (Springer, 2016), pp. 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46448-0_2

Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R. & Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection, in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition , pp. 779–788. (2016) https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.91

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger, in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition , pp. 6517–6525. (2017) https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2017.690

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An incremental improvement. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.02767 (2018). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1804.02767

Bochkovskiy, A., Wang, C.Y. & Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.10934 (2020). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2004.10934

Jocher, G. et al. YOLOv5 by Ultralytics. https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5 (2020)

Li, C.Y. et al. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.02976 (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2209.02976

Wang, C.Y., Bochkovskiy, A. & Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.02696 (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2207.02696

Jocher, G., et al. YOLO by Ultralytics. https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (2023)

Carion, N., Massa, F., Synnaeve, G., Usunier, N., Kirillov, A. & Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.12872 (2020). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2005.12872

Tang, M. et al. A strip steel surface defect detection method based on attention mechanism and multi-scale maxpooling. Measurement Science and Technology 32(11), 115401. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6501/ac14ea (2021).

Fang, J., Tan, X. & Wang, Y. ACRM: Attention Cascade R-CNN with Mix NMS for Metallic Surface Defect Detection, in 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR) (IEEE, 2021), pp. 423–430. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPR48806.2021.9413248

Ren, X. et al. YOLO-Lite: An efficient lightweight network for SAR ship detection. Remote Sensing 15(15), 3771. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15153771 (2023).

Jianbo Lu, .L. & Yu, MiaoMiao. Lightweight strip steel defect detection algorithm based on improved yolov7. Scientific reports p. 13267 (2024)

Qin, R., Chen, N. & Huang, Y. EDDNet: An Efficient and Accurate Defect Detection Network for the Industrial Edge Environment, in 2022 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability and Security (QRS) (IEEE, 2022), pp. 854–863. https://doi.org/10.1109/QRS57344.2022.00097

Zhong, H., et al., Steel surface defect detection based on an improved YOLOv5 model, in 2023 5th International Conference on Intelligent Control, Measurement and Signal Processing (ICMSP) (IEEE, 2023), pp. 51–55. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMSP57120.2023.10052203

Yu, T., Luo, X., Li, Q. & Li, L. CRGF-YOLO: An optimized multi-scale feature fusion model based on YOLOv5 for detection of steel surface defects. International Journal of Computational Intelligence Systems 17(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44196-022-00192-4 (2024).

Yuting, S. & Hongxing, L. A deep learning based dislocation detection method for cylindrical silicon growth process. Applied Intelligence 53(8), 9188–9203 (2023).

Ning, T., Wu, W. & Zhang, J. Small object detection based on YOLOv8 in UAV perspective. Pattern Analysis and Applications 27(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10044-023-01052-7 (2024).

Zhu, X., Liu, J., Zhou, X., Qian, S. & Yu, J. Enhanced feature fusion structure of YOLOv5 for detecting small defects on metal surfaces. International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics 14(6), 2041–2051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13042-022-01682-w (2023).

Wan, D. et al. YOLO-MIF: Improved YOLOv8 with multi-information fusion for object detection in gray-scale images. Advanced Engineering Informatics 62, 102709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2023.102709 (2024).

Wang, C. & Xie, H. MeDERT: A metal surface defect detection model. IEEE Access 11, 35469–35478. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3272922 (2023).

Li, T., Wang, Y., Shen, C. et al. Generalized focal loss: Learning qualified and distributed bounding boxes for dense object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.04388 (2020). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2006.04388

Zheng, Z., et al. Distance-IoU Loss: Faster and Better Learning for Bounding Box Regression, in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 34 , pp. 12993–13000. (2020) https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v34i07.6999

Zhang, H., Wang, Y., Dayoub, F. & Sünderhauf, N. VarifocalNet: An IoU-aware dense object detector, in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition , pp. 8514–8523. (2021) https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.00841

Dauphin, Y.N., Fan, A., Auli, M. & Grangier, D. Language modeling with gated convolutional networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1612.08083 (2017). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1612.08083

Arik, S.Ö., Chrzanowski, M., Coates, A. et al. Conditional Gated Linear Units for Speech and Language Processing, in 2017 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) (IEEE, 2017), pp. 5000–5004. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2017.7953075

Cho, K., van Merrienboer, B., Gulcehre, C. et al. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder–decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1406.1078 (2014). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1406.1078

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Computation 9(8), 1735–1780. https://doi.org/10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735 (1997).

Lin, T.Y., Dollár, P., Girshick, R., He, K., Hariharan, B. & Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection, in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition , pp. 2117–2125. (2017) https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2017.106

Liu, S., Qi, L., Qin, H., Shi, J. & Jia, J. Path Aggregation Network for Instance Segmentation, in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition , pp. 8759–8768. (2018) https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2018.00913

Tan, M., Pang, R. & Le, Q.V. EfficientDet: Scalable and Efficient Object Detection, in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition , pp. 10781–10790. (2020) https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.01080

Kang, M., Ting, C. M., Ting, F. F. & Phan, R. C. W. ASF-YOLO: A novel YOLO model with attentional scale sequence fusion for cell instance segmentation. Image and Vision Computing 147, 105057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imavis.2023.105057 (2024).

Xie, S., Girshick, R., Dollár, P., Tu, Z. & He, K. Aggregated Residual Transformations for Deep Neural Networks, in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition , pp. 5987–5995. (2017) https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2017.634

Rezatofighi, H., Tsoi, N., Gwak, J., Sadeghian, A., Reid, I. & Savarese, S. Generalized Intersection over Union: A Metric and a Loss for Bounding Box Regression, in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition , pp. 658–666. (2019) https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2019.00075

Zhang, Y. F. et al. Focal and efficient IoU loss for accurate bounding box regression. Neurocomputing 506, 146–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2022.07.004 (2022).

Bochkovskiy, A. SIoU loss: More powerful learning for bounding box regression. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.12740 (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2205.12740

Ma, X., Dai, X., Bai, Y., Wang, Y. & Fu, Y. Rewrite the Stars, in 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (2024)

Shi, D. TransNeXt: Robust Foveal Visual Perception for Vision Transformers, in 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (2024)

Li, H., Li, J., Wei, H. et al. Slim-neck by GSConv: a lightweight-design for real-time detector architectures. Journal of Real-Time Image Processing 21(3) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11554-023-01263-0

Zhang, H., Xu, C. & Zhang, S. Inner-IoU: More effective intersection over union loss with auxiliary bounding box (2023)

Zhang, H. & Zhang, S. Focaler-IoU: More focused intersection over union loss (2024)

Wu, C. & He, T. Efficient minor defects detection on steel surface via res-attention and position encoding. The Visual Computer https://doi.org/10.1007/s00371-024-03583-0 (2024).

Zhang, H., et al. Surface defect detection of hot rolled steel based on multi-scale feature fusion and attention mechanism residual block. Scientific Reports 14(7671) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57990-3

Wang, C.Y., Yeh, I.H. & Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.13616 (2024). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.13616

Wang, A., et al. YOLOv10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14458 (2024). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.14458

Jocher, G. & Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLOv11 (2024). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2412.14790

Acknowledgements

The study is supported by the Shaanxi Basic Science Research Institute under the Research Program on the Dynamics of Neural Systems under Noise Perturbation and Micro/Nano Regulation (Project No. 22JSZ008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuan Liu: Methodology, Investigation, Software, Writing - Original Draft, Visualization. Yilong Liu: Methodology, Investigation, Software, Writing - Original Draft, Visualization. Xiaoyan Guo: Investigation, Validation, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision. Xi Ling: Conceptualization, Data Curation. Qingyi Geng: Conceptualization, Data Curation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics Approval

This study does not involve any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Liu, Y., Guo, X. et al. Metal surface defect detection using SLF-YOLO enhanced YOLOv8 model. Sci Rep 15, 11105 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94936-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94936-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Few-shot cross-episode adaptive memory for metal surface defect semantic segmentation

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Real-time hybrid AI for strip steel surface monitoring in industry 4.0

The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology (2026)

-

Concrete slump detection based on light-AWGAM-YOLOv8n

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Navigating beyond sight: a real-time 3D audio-enhanced object detection system for empowering visually impaired spatial awareness

Signal, Image and Video Processing (2025)