Abstract

Background: Unplanned readmissions are associated with increased mortality among older patients. This study investigated the effects of changes in physical function and frailty on unplanned readmissions in middle-aged and older patients after discharge. Methods: This longitudinal study recruited participants through convenience sampling from the general wards of a medical center in northern Taiwan. They were aged 50 years or older and identified as being at high risk for readmission or mortality following discharge. Baseline data were collected through interviews conducted the day before discharged, while follow-up data were obtained through interviews at 1, 2, and 3 months post-discharge. Generalized estimating equation (GEE) was used for statistical analysis, incorporating all tracked variables, including physical function and frailty. Results: A total of 230 participants were recruited, each followed three times after discharge. The unplanned readmission rates at 1, 2, and 3 months post-discharge were 2%, 8%, and 14%, respectively. Participants with poorer physical function (odds ratio [OR] = 1.60 [1.27–2.02]) and more severe frailty symptoms (OR = 3.16 [1.45–6.83]) had significantly higher odds of unplanned readmission. The interaction between the time and frailty indicated a significantly lower likelihood of unplanned readmission over time (OR = 0.73 [0.54–0.98]). Conclusions: Declining physical function and frailty are key risk factors for unplanned readmission in older patients. Effective strategies to reduce this risk include monitoring physical function and frailty symptoms and providing supportive care services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hospital readmissions are a major concern for older patients due to their impact on health, quality of life, and healthcare systems. In the United States, nearly 20% of discharged patients are readmitted within 30 days, and 50–70% of these patients are readmitted or deceased within one year. The annual cost of unplanned readmissions is estimated to be US$15 to 20 billion1. Research in Taiwan has reported a one-year readmission or mortality rate of 20–48% among elderly individuals after discharge2. Patients readmitted shortly after discharge face an increased risk of mortality3,4 and a decline in health-related quality of life5. Unplanned readmissions also contribute to psychological distress in older patients, leading to depression and anxiety6,7.

Several studies have demonstrated that discharge planning service can reduce readmission rates8,9. These services help prevent avoidable readmissions, improve post-discharge quality of life, and alleviate the financial burden on healthcare systems10. A meta-analysis of retrospective medical record reviews estimated a median avoidable readmission rate of 27%, ranging from 5 to 79%11. An observational study in the United States, which analyzed 1,000 inpatients across 12 medical centers, found that a quarter of readmissions could be prevented by enhancing communication between healthcare providers and patients, improving discharge preparation, strengthening disease monitoring, and supporting patient self-management12. Additional studies have shown that interventions such as medication safety counseling, advanced care planning, enhanced caregiver education, and improved continuity of post-discharge care can effectively reduce unplanned readmissions13,14. Addressing the root causes of unplanned readmissions requires not only identifying risk factors but also implementing evidence-based discharge planning services.

Risk factors for unplanned admissions include advanced age, comorbidities, infection during hospitalization, length of hospital stay, physical function, and frailty15,16,17. Identifying high-risk patients before discharge, providing comprehensive discharge planning services, and implementing interdisciplinary home care teams may help reduce readmissions18,19. However, the transition from hospital to home can impact patients’ access to care services and lead to functional changes, which may, in turn, influence health outcomes and readmission risk20,21.

Most previous studies on adverse discharge outcomes have focused on hospitalized elderly patients, but unplanned readmission among middle-aged patients have recently gained attention. Research indicates that the prevalence of comorbidities and mobility impairments is increasing in the middle-aged population22,23. Moreover, middle-aged patients with myocardial infarction have been shown to have a higher risk of readmission than elderly patients, adding strain to the healthcare system24. Additionally, while many studies have examined predictors of readmission using baseline data at discharge, few have accounted for time-series changes in patient conditions during the post-transition period. This study aims to bridge this gap by examining risk factors for unplanned readmission in middle-aged and older patients. Baseline patient data at discharge were used as fixed factors, while longitudinal data on care styles, follow-up appointments, the usefulness of care services, and changes in physical function and frailty at different time points after discharge were collected. Furthermore, generalized estimating equations (GEE) were applied to develop a predictive model for unplanned readmissions, enabling multivariate analysis of repeated measures to address data correlation issues inherent in generalized linear models25.

Methods

Participants

Taiwan has a national health insurance system and implements prioritized medical care system classified by the Ministry of Health and Welfare into medical centers, regional hospitals, district hospitals, and primary clinics. Medical centers are responsible for research, teaching, and the treatment of critically ill patients. This study was conducted in collaboration with a medical center in northern Taiwan, where inpatients from general medical and surgical wards were recruited. Patients from intensive care units, respiratory care wards, burn wards, and psychiatric wards were excluded.

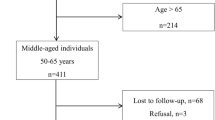

This was a longitudinal study. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they: (1) were aged 50 years and above, (2) were hospitalized in a general ward, (3) had not been hospitalized in any hospital within the past three months (to exclude readmissions related to recent hospitalizations), (4) were not hospitalized for routine treatments (e.g., chemotherapy for cancer) or notifiable infectious diseases that must be reported to the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control, (5) Were determined to require discharge planning services before discharge, and (6) were capable of communication. Patients were excluded if they were unconscious, had cognitive impairment, or were receiving hospice care upon admission. During hospitalization, each included patient was assessed for the need for discharge planning services using the hospital’s high-risk patient screening tool, which considered factors such as gender, age, BMI, disability certification, hospitalization history, diagnosis (internal medicine or surgery), toileting ability, and need for tube assistance. Patients identified as high-risk for readmission or mortality were referred to a case manager (discharge planning supervisor), who evaluated their eligibility for the study. If patients met the criteria and agreed to participate, the supervisor notified the research team, which then conducted three follow-up interviews. All questionnaire data were collected by the interviewer through paper-pencil records. Data collection period was from March 2021 to July 2022. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all interviews were conducted by telephone to minimize infection risks.

The GLIMMPSE program (URL:http://glimmpse.samplesizeshop.org/) was used to calculate the required sample size for longitudinal studies. With a significance level of 0.05, power of 0.8, and three measurement points, the required sample size was 82. We used the program GLIMMPSE for computing sample size for longitudinal designs26. A separate calculation for the prediction model used the expected readmission rate (0.4) and expected correlation strength (0.35), yielding a required sample size of 22427.

Data collection

First interview (baseline factors)

A senior research assistant conducted individual telephone interviews, including the baseline and follow-up interviews. Prior to formal data collection, 10 pilot interviews were conducted to refine the interview process. Any concerns during formal interviews were documented, and if necessary, a re-interview was conducted within two days to clarify responses. The first telephone interview was conducted before discharge to collect baseline data, including:

-

(1)

Demographic characteristics: age, sex (male and female), height, weight, and presence of a government-issued disability or severe illness certificate (yes/no).

-

(2)

Hospitalization indicators: main diagnosis, surgery (yes or no), use of a tube (nasogastric tube, tracheostomy, or urethral catheter), length of hospital stay, and functional mobility (rolling over, getting out of bed, and walking, as perceived by the patient).

-

(3)

Health status: medical history (high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes, stroke, kidney disease, liver disease, lung disease, malignant tumors, and dementia), history of hospitalization within the past year (yes/no), and BMI (calculated from self-reported height and weight).

Follow-up interviews (follow-up factors)

Three follow-up telephone interviews were conducted at 1, 2, and 3 months after discharge. The same variables were assessed in each interview:

-

(1)

Physical function: The activities of daily living (ADL) inventory was used to assess physical function28. Six activities were evaluated: eating, turning (getting up and down from a bed or chair), indoor walking, dressing, bathing, and toileting. Each activity was classified into three levels: needs help, needs assistive devices, and does not need help. Participants requiring assistance or assistive devices received 1 point per item (total score: 0–6, with higher scores indicating worse function). Monitoring ADL after discharge has been suggested to prevent functional deterioration, readmission, or death29.

-

(2)

Frailty: The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) index was used to assess frailty symptoms. It includes: weight loss (≥ 3 kg or ≥ 5% body weight lost unintentionally in the past year), lower extremity function (unable to stand from a chair five times without hand support), decreased energy (lack of energy to perform daily activities in the past week), participants answered yes/no, with 1 point per “yes” response (range: 0–3). A Taiwanese study found a moderate correlation (r = 0.51)* between the SOF and Fried’s Frailty Phenotype Index30.

-

(3)

Use of care services after discharge: participants reported whether they had received home-based care services (e.g., nursing care, rehabilitation, transportation, or assistive aids) since the last interview.

-

(4)

Use of medical services after discharge: Participants were asked about outpatient visits and unplanned readmissions since the last interview. Unplanned readmissions were defined as unscheduled hospital admissions to the same specialty via the emergency department within a specified period after discharge.

To assess data stability across interviews, we calculated the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC). The ICC values for ADL (72.3%) and frailty (75.4%) indicated adequate reliability for intra-rater consistency.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill., USA). Frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations were used to summarize participants’ demographic data, hospitalization indicators, and health status. Variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to check for multi-collinearity in regression models.

The follow-up data were repeated measures at multiple time points. The associations between independent variables (baseline characteristics, hospitalization indicators, health status, physical function, frailty, care services, and medical services) and the dependent variable (unplanned readmission, OR) were examined by Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) Analysis. Interacting effects between time points and frailty were incorporated to assess time-dependent influences.

Ethical considerations

Participants were informed of the study purpose, data collection methods, their right to withdraw at any time, and privacy protection. Before participation, oral informed consent was obtained from both participants and service supervisors. Participants could contact the research team for further inquiries. Ethical approval was granted by the Taipei Medical University - Joint Institutional Review Board (TMU-JIRB) (N201901029).

Results

Data were collected from 230 participants. Regarding the participants’ demographic characteristics, 140 (60.9%) were women; the average age was 74.7 years (standard deviation [SD] = 10.2), and 40 (17.4%) participants had a disability or severe illness. Regarding current hospitalization indicators, 65.6% of the patients had undergone surgery, 47.8% had used tubes during hospitalization, and 66.5% were unable to move on their own. The average length of stay was 8.3 days, and the median length of stay was 6 days. Regarding health status indicators, hypertension occurred most frequently (in 57.4% of patients), followed by heart disease (34.8%) and diabetes (31.3%). Furthermore, 26.1% of the participants had been hospitalized within 1 year of their current hospitalization. In accordance with the World Health Organization definitions, 42.2% of the participants were considered to have a normal BMI (18.5–24.0 kg/m2), 5.2% were considered underweight (< 18.5 kg /m2), and 52.6% were considered overweight (> 24.0 kg/m2). The unplanned readmission rates at 1, 2, and 3 months after discharge were 2%, 8%, and 14%, respectively (Table 1).

The collinearity diagnosis results of ADL and frailty in the three follow-up data were 1.275–1.285, showing that there was no obvious collinearity problem between these two variables. All baseline and follow-up factors were incorporated into the GEE model to enable analysis of the effects of the independent variables on unplanned readmissions at each time point (Table 2). Among the baseline factors, significant effects were identified for age (OR = 1.04 [1.00–1.08]), operation (OR = 0.44 [0.21–0.93]), functional mobility (OR = 0.39 [0.15–0.98]), comorbidity (OR = 1.37 [1.06–1.76]), and hospitalization experience (OR = 2.72 [1.27–5.82]). Among the follow-up factors, worse physical function (OR = 1.63 [1.37–1.93]) and more symptoms of frailty (OR = 1.96, [1.44–2.68]) were associated with a significantly higher likelihood of unplanned readmission. Participants who returned to an outpatient clinic after discharge had a lower likelihood of unplanned readmission (OR = 0.80 [0.29–2.24]) but no significant. Use of home care services, transportation, and assistive aids after discharge had no significant effect on the likelihood of an unplanned readmission.

All baseline and follow-up significant variables and the interaction between the time points and frailty were included in the GEE model (Table 3). The results revealed that patients with worse physical function (OR = 1.60 [1.27–2.02]) and more symptoms of frailty (OR = 3.16 [1.45–6.83]) had a significantly higher likelihood of unplanned readmission and that patients who undergone surgery at baseline had a significantly lower likelihood of unplanned readmission (OR = 0.30 [0.11–0.83]). The interaction between the time effect and frailty also indicated a significantly lower likelihood of unplanned readmission (OR = 0.73 [0.54–0.98]). We estimated a statistical power of 81.02% from power analysis.

Discussion

This longitudinal study examined the risk factors for unplanned readmissions in high-risk middle-aged and older patients using the GEE model. The results identified surgery during the baseline hospitalization as a protective factor, whereas poor physical function and frailty at follow-up were significant risk factors for unplanned readmissions. Additionally, the interaction between time and frailty was a key predictor of readmission.

Older patients with poorer physical function and more symptoms of frailty were more likely to experience unplanned readmissions after discharge. Previous studies have demonstrated that mobility limitations and frailty are strong predictors of readmission; however, these studies often assessed these factors only at discharge without longitudinal follow-ups16,18,19. A US study using Medicare claims data identified functional status as a crucial patient-level predictor of readmission16,31. A cohort study in Israel highlighted that functional assessment at discharge could help detect patients at risk of readmission32. A nested case-control study in Spain found that frailty was a key predictor of heart failure readmission within one month of discharge, though it did not find an association between functional activity and readmission33. A review article reported that functional status at discharge could also predict post-discharge mortality in older patients34. Many patients have poor mobility and frailty symptoms at discharge, as they are still recovering from an acute phase of illness. Their readmission may stem from severe health complications developed during hospitalization.

In this study, ADL and SOF scores were assessed at three time points post-discharge to track changes in physical function and frailty. Patients with declining physical function and worsening frailty had significantly higher readmission rates. A retrospective observational study in Japan found that ADL limitations at discharge and ADL decline were associated with poor outcomes, including mortality and readmission in older pneumonia patients35. Reduced ADL ability can impair disease management and self-care, increasing the likelihood of injury and readmission. This study also found that inability to use the toilet independently was the most predictive ADL factor for readmission. This may be due to an increased risk of infection, falls, and other complications. Identifying toileting difficulties in ADL assessments could help healthcare professionals develop discharge planning strategies to prevent readmission.

The study revealed that the interaction between time and frailty was negatively associated with unplanned readmissions. Longer time post-discharge combined with increased frailty symptoms may act as barriers to seeking medical treatment due to progressive functional decline, making travel and hospital visits more difficult, increased dependence on caregivers, requiring more manpower and transportation assistance. A study by Garcia-Gutierrez et al. found that frailty predicted short-term readmission, but its predictive ability for long-term adverse outcomes was unclear33. The interaction between time and frailty suggests that reduced healthcare accessibility and willingness to seek treatment may lead to more severe health complications and higher long-term medical costs.

A major strength of this study was its longitudinal design, which allowed for robust estimations of the associations between physical function, frailty, and readmissions over time. This design enabled the verification of risk factors beyond baseline assessments, providing a more comprehensive understanding of post-discharge readmission risks. However, this study has several limitations. The study focused on patients meeting specific criteria, excluding those with certain diseases or different diagnoses. Disease severity was not included as a hospitalization indicator, limiting control over this variable. While surgery at baseline was identified as a protective factor, the study did not classify specific types of surgery, which may have influenced post-discharge physical activity and recovery. Many outpatient visits post-discharge were linked to chronic disease management. It was challenging to distinguish whether return visits were due to the original hospitalization diagnosis or other chronic conditions. The SOF index may introduce estimation bias, as it lacks a universally agreed-upon cut-off point. More validated instruments with strong reliability and validity could yield more robust frailty assessments. Self-assessments of ADL and frailty may differ from in-person evaluations, introducing potential response bias. Data collection from one hospital may introduce sampling bias and limit generalizability to other healthcare settings.

Conclusion

Physical function deterioration and frailty were significant risk factors for unplanned readmissions in older patients. Providing transportation services can facilitate timely access to medical care, potentially reducing readmissions. Healthcare providers should actively monitor patients’ physical function and frailty symptoms post-discharge to identify high-risk individuals.

Supportive care services (e.g., home care, rehabilitation, assistive aids) should be incorporated into discharge planning to reduce readmission risk. By implementing targeted interventions based on functional status and frailty progression, healthcare professionals can improve post-discharge outcomes and reduce the burden of unplanned readmissions among middle-aged and older patients.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the relevant research is still in progress, but they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Jencks, S. F., Williams, M. V. & Coleman, E. A. Rehospitalizations among patients in the medicare Fee-for-Service program. N. Engl. J. Med. 360 (14), 1418–1428 (2009).

Yen, H. Y., Lin, S. C. & Chi, M. J. Exploration of Risk Factors for High-Risk Adverse Events in Elderly Patients After Discharge and Comparison of Discharge Planning Screening Tools.. Vol. 54(1). 7–14 (2022).

Yen, H. Y., Chi, M. J. & Huang, H. Y. Effects of discharge planning services and unplanned readmissions on post-hospital mortality in older patients: A time-varying survival analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 128, 104175 (2022).

Shaw, J. A. et al. Thirty-Day hospital readmissions: A predictor of higher All-cause mortality for up to two years. Cureus 12 (7), e9308 (2020).

Kim, H. S., Kim, Y. & Kwon, H. Health-related quality of life and readmission of patients with cardiovascular disease in South Korea. Perspect. Public. Health. 141 (1), 28–36 (2019).

Alzahrani, N. The effect of hospitalization on patients’ emotional and psychological well-being among adult patients: an integrative review. Appl. Nurs. Res. 61, 151488 (2021).

Blakey, E. P. et al. What is the experience of being readmitted to hospital for people 65 years and over? A review of the literature. Contemp. Nurse. 53 (6), 698–712 (2017).

Braet, A., Weltens, C. & Sermeus, W. Effectiveness of discharge interventions from hospital to home on hospital readmissions: A systematic review. JBI Evid. Synth. 14(2), 106–173 (2016).

Zuckerman, R. B. et al. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital. Readmissions Reduct. Program. 374 (16), 1543–1551 (2016).

Alper, E., O’Malley, T. A. & Greenwald, M. Hospital Discharge and Readmission. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/hospital-discharge-and-readmission#H14. Accessed 15 June 2022 (2022).

van Walraven, C. et al. Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: A systematic review. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. 183(7), E391–E402 ( 2011).

Auerbach, A. D. et al. Preventability and causes of readmissions in a National cohort of general medicine patients. JAMA Intern. Med. 176 (4), 484–493 (2016).

Facchinetti, G. et al. Continuity of care interventions for preventing hospital readmission of older people with chronic diseases: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 101, 103396 (2020).

Leonhardt-Caprio, A. M. et al. A Multi-Component transition of care improvement project to reduce hospital readmissions following ischemic stroke. Neurohospitalist 12 (2), 205–212 (2022).

Ghosh, A. K. et al. Association between Racial disparities in hospital length of stay and the hospital readmission reduction program. Health Serv. Res. Managerial Epidemiol. 8, 23333928211042454–23333928211042454 (2021).

Keeney, T. et al. Frailty and function in heart failure: predictors of 30-Day hospital readmission?? J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 44 (2), 101–107 (2021).

Tavares, M. G., Tedesco-Silva Junior, H. & Pestana, J. O. M. Early hospital readmission (EHR) in kidney transplantation: a review Article. J. Bras. Nefrol. 42 (2), 231–237 (2020).

Cunha Ferré, M. F. et al. 72-hour hospital readmission of older people after hospital discharge with home care services. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 38 (3), 153–161 (2019).

Ma, C. et al. Hospital readmission in persons with dementia: A systematic review. 34(8), 1170–1184 (2019).

Kumar, A. et al. Comparing post-acute rehabilitation use, length of stay, and outcomes experienced by medicare fee-for-service and medicare advantage beneficiaries with hip fracture in the united States: A secondary analysis of administrative data. PLoS Med. 15 (6), e1002592 (2018).

Levi, S. J. Posthospital setting, resource utilization, and self-care outcome in older women with hip fracture. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 78 (9), 973–979 (1997).

Kim-Dorner, S. J. et al. Age- and gender-based comorbidity categories in general practitioner and pulmonology patients with COPD. Npj Prim. Care Respiratory Med. 32 (1), 17 (2022).

Avendano, M. et al. Health disadvantage in US adults aged 50 to 74 years: A comparison of the health of rich and poor Americans with that of Europeans. Am. J. Public Health. 99 (3), 540–548 (2009).

Khera, R. et al. Comparison of readmission rates after acute myocardial infarction in 3 patient age groups (18 to 44, 45 to 64, and ≥ 65 Years) in the united States. Am. J. Cardiol. 120 (10), 1761–1767 (2017).

Liang, K. Y. & Zeger, S. L. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 73 (1), 13–22 (1986).

Guo, Y. et al. Selecting a sample size for studies with repeated measures. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13 (1), 100 (2013).

Riley, R. D. et al. Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model. BMJ 368, m441 (2020).

Katz, S. et al. Studies of illness in the aged: the index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185 (12), 914–919 (1963).

Sager, M. A. et al. Functional outcomes of acute medical illness and hospitalization in older persons. Arch. Intern. Med. 156 (6), 645–652 (1996).

Hu, B. et al. The validity of the study of osteoporotic fractures index (SOF) index for assessing community-based older adults in Taiwan. 16(2)(Suppl 1), 1015 (2018).

Greysen, S. R. et al. Functional impairment and hospital readmission in medicare seniors. JAMA Intern. Med. 175 (4), 559–565 (2015).

Tonkikh, O. et al. Functional status before and during acute hospitalization and readmission risk identification. J. Hosp. Med. 11 (9), 636–641 (2016).

Garcia-Gutierrez, S. et al. Factors related to early readmissions after acute heart failure: a nested case–control study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 23 (1), 17 (2023).

Preyde, M. & Brassard, K. Evidence-based risk factors for adverse health outcomes in older patients after discharge home and assessment tools: A systematic review. J. Evid. Based Soc. Work. 8 (5), 445–468 (2011).

Yamada, K. et al. Activities of daily living limitation and functional decline during hospitalization predict 180-day readmission and mortality in older patients with pneumonia: A single-center, retrospective cohort study. Respir. Med. 234, 107830 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The funding sources of this work was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan under grants MOST 108-2314-B-038-074-MY3, and National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan under grants NSTC 113-2314-B-038-093-MY3.

Funding

This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (Grant numbers [MOST 108-2314-B-038-074-MY3]) and National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (Grant numbers [NSTC 113-2314-B-038-093-MY3]).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Sheau-Wen Kan, Mei-Ju Chi and Hsin-Yen Yen. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Sheau-Wen Kan, Hao-Yun Huang and Hsin-Yen Yen and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Taipei Medical University-Joint Institutional Review Board (N201901029).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kan, SW., Yen, HY., Chi, MJ. et al. Influence of physical function and frailty on unplanned readmission in middle-aged and older patients discharged from a hospital: a follow-up study. Sci Rep 15, 10003 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94945-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94945-8