Abstract

Malaria continues to be a public health problem in Nigeria. Effective vector control has been acknowledged as one of the major strategies to combat malaria in Nigeria. In order to inform context-specific policies, there is need to understand the species niche/colonization and geographical distribution of local Anopheles mosquitoes in different geographical areas in Nigeria. Therefore, this study was designed to model the distribution of Anopheles gambiae s.l. in Osun State, Nigeria. Immature stages of Anopheles mosquitoes were collected from 17 Local Government Areas (LGAs) of Osun State between 2022 and 2023, resulting in the identification of over 20,000 Anopheline mosquitoes. Of these, 146 breeding sites were identified. Two sibling species of An. gambiae s.l were later confirmed using molecular techniques (An. gambiae s.s. and An. coluzzii) with 99% of the Anopheles being An. coluzzii in all the 17 LGAs. The results were modelled using Random Forest to predict their potentially suitable habitats across the entire state. A total of 23 environmental variables (19 bioclimatic and four topographic) were used in the model, resulting in maps of the potential geographical distribution of dominant vector species under current climatic conditions. The model suggests that members of the Anopheles gambiae s.l. encountered would be found in the three senatorial districts (from high to moderate), with more suitable areas in the central part of the state. Temperature-related climatic conditions seems to be ranked higher in order of variable importance that contributed to the distribution of these species. Mean diurnal range (monthly temperature fluctuation) and temperature of the coldest month seem to be strongly associated with the presence of these species. Our model suggested areas with higher monthly temperature fluctuations in the state (between 9 and 10 °C) to support the breeding of Anopheles species, and they are likely to be abundant in areas with lower temperature during the coldest month (wet season) of the year (between 18 and 19 °C). The results of this study provide a baseline data allowing decision-makers to monitor the distribution of these species and establish a management plan for future mosquito surveillance and control programs in Osun State.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global burden of vector-borne diseases (VBD) is alarming, causing serious public health concern. Malaria has been a common household name in Nigeria, and yet kills many children under 5 years old and pregnant women anually1. Nigeria accounted for almost half of the global cases of malaria in 20222 and recorded 31.1% of all deaths caused by malaria, globally2. One major reason for the high malaria prevalence reported in Nigeria, is the presence and abundance of female Anopheles mosquitoes, which transmits malaria from an infected person to another non-infected person. In Nigeria, members of the Anopheles gambiae s.l. has been incriminated as the major malaria vector, responsible for the continuing transmission of malaria in the country3. The sibling species of this complex often found in Nigeria include An. gambiae, An. arabiensis, and An. coluzzii3,4. These species are morphologically similar and can only be distinguished via molecular analysis5. The distribution and abundance of adult Anopheles mosquitoes are predicated on the presence and productivity of larval breeding habitats6.

Much of the success achieved in combating malaria has been through large investments in vector control, and many efforts have been put in place to support this strategy1,3. However, successful malaria vector control requires adequate knowledge of vector distribution and dynamics3. For instance, the members of Anopheles gambiae s.l. may share the same ecological niche but thrive in varying environmental conditions which in turn determines their geographical distribution7,8. Therefore, understanding the climatic and environmental factors influencing the distribution of dominant malaria vectors in the country will be a valuable tool for policymakers and implementers to develop targeted interventions.

The crux of vector control strategy in Nigeria has relied on the use of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) through mass distribution3. Despite the high number of LLINs distributed in the country, malaria prevalence is still high, with Nigeria accounting for 54% of African malaria burden1. Osun State is one of the endemic states for malaria in Nigeria, and recent malaria indicator surveys indicated that malaria is still prevalent in the State, with a prevalence of 27.6% among children under 5, ranking above many states in Nigeria, despite the over 72% net ownership rate recorded in the State9. This might be due to constant resistance demonstrated by malaria vectors to the active ingredient used in the LLINs, severely limiting targeted malaria vector control efforts3. In light of this, other vector control methods, such as larviciding and environmental modification, become important alternatives. Due to the limited movement of the mosquito’s immature stages compared to flying adults, the control of immature stages could be more efficient10 in comparison to adults. To effectively deploy any alternative control measure in Osun State, there is need for localized knowledge on the ecology, and spatial distribution of the malaria vectors in the state. Unfortunately, there is paucity of information in this regard.

Spatial modeling, such as species distribution modeling (SDM) can be used to bridge knowledge gaps in the distribution of organisms. Its application in malaria vector distribution can be used to bridge data gaps, especially in areas where no data are available. This will allow evidence-based estimates to be made on the risk of malaria transmission in areas not covered by routine surveillance11. SDM is a useful tool that extracts and identifies the fundamental boundaries of a species’ niche at each occurrence location in a selected dataset from a set of relevant environmental covariates. Predictions from SDM can fill the voids resulting from surveillance data shortages12. This study, therefore, presents the spatial distribution of malaria vectors sampled in 17 LGAs and the predicted species distribution model that addresses information gaps on malaria vectors distribution in Osun state, Nigeria. The overall aim is to provide evidence-based predictions on malaria vectors distribution for public health decision-makers to guide future state surveillance and control programs in Osun State.

Materials and methods

Study area

Mosquito larval sampling was carried out in 17 local government areas (LGAs) of Osun State, Nigeria, representing the three senatorial districts. Osun State, Nigeria (7.5629° N, 4.5200° E) has 30 LGAs with an estimated population of about 4.7 million as at 201613. The state is divided into three senatorial districts, namely: Osun East, Osun West and Osun Central (Fig. 1). Geographically, the state is divided between the Nigerian lowland forests in most of the state and drier Guinean forest-savanna mosaic in the North. Generally, the climate in the state is typically tropical with two distinct seasons: rainy (May to October) and dry (November to April). The mean annual temperature in the state ranges from 24.0 °C to 28.35 °C, with approximately 127.75 millimeters of annual rainfall and has about 237.62 rainy days (65.1% of the time). The main method of vector control in the study areas is insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs). In the past 5 years, more ITNs have been deployed in the state through free mass distributions, resulting into high coverage (over 70%) in the study areas9.

Mosquito collection and identification

The World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s entomological protocols for field and laboratory studies on malaria vectors were employed in carrying out the studies14. For larval sampling, breeding sites were first identified through local knowledge and larval prospection. Anopheles larvae were collected weekly between 0700 h and 1100 h between January 2022 to December 2023 (spanning both dry and wet seasons) from identified breeding sites such as permanent water bodies, rice fields, small water pools, or impoundments, using a dipping method described by WHO14 and the location of all sites were georeferenced using a GPS device. Sampling was done proportionally to the size of the breeding site, ensuring larger sites were adequately represented. Standard dippers were used to collect larvae, with three dips per square meter taken from the edges and middle of each site to ensure representative sampling. Information on the larval habitat characteristics (types, size, presence or absence of vegetation, presence of Anopheles spp., exposure to sunlight) were also recorded (Supplementary file 1).

More than 25,000 mosquito larvae were collected and about 20,000 morphologically identified to confirm they are Anopheles gambiae s.l larvae. Collected larvae were transported to the insectary. The larvae were reared to adult under ambient laboratory conditions and the emerged adults were identified morphologically by trained personnel and finally validated by the Principal Investigator using the keys of Gilles and Coetzee15 under × 1000 Dino-lite HD color CMOS sensor high speed digital microscope (model number, AD4113T-12 V). After identification, the mosquitoes were sorted into Anopheline and Culicines. Mosquitoes belonging to the Anopheles gambiae s.l. were further identified using the An. gambiae species specific PCR16.

Environmental data

Climatic variables such as temperature and precipitation influence species distribution at global and meso scales, topographic variables such as altitude and aspect have more influence at meso and topo-scales whereas land-cover variables such as percent canopy cover can influence distributions at the micro-scale17. Hence, climatic and topographic level variables were used here to predict the distribution of Anopheles gambiae. We considered 19 environmental and four topographical variables as potential predictors of the target species habitat distribution3,18,19,20. These variables were chosen based on their biological relevance to the target species distributions3,21,22,23. The nineteen bioclimatic variables with a 30 s spatial resolution (about 1 km) were downloaded from the WorldClim database (http://www.worldclim.org/)24. Elevation data 1 km2 - resolution was obtained from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM). The elevation data was used to generate slope, aspect, and hillshade (all in degrees) using the Spatial Analyst tool/surface in using ArcGIS 10.7.1 software. The coordinates for all presence and absence data were taken in decimal degrees (to five decimal places) and plotted using Google Earth to check for annotation errors. After downloading the climatic files, the Osun layer was extracted by using a boundary mask (Table 1).

Modelling

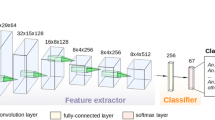

To model the distribution of the target species and predict its presence probability, we employed a Random Forest (RF) algorithm, a widely-used ensemble machine learning technique known for its robust performance in handling complex relationships between predictor variables and response variables. RF constructs an ensemble of decision trees (non-linear models) using bootstrap samples from the original values and outputs an average of their prediction results25. Within a tree, each node considers a randomized subset of the original variables. Bootstrapping, variable randomization and averaging are critical features that make RF a robust machine learning technique especially for analysis of complex, nonlinear and highly dimensional data25,26,27. The analysis was conducted in R programming language, utilizing the ‘dismo’, ‘raster’, ‘pROC’, and ‘Radom Forest’ packages. For the study area, it requires both species presence and absence data and environmental variable (continuous or categorical) layers. For modeling presence/absence, we built a Random Forest regression using the predictor variables and the binary response variable, indicating species presence (1) or absence (0), which generates an estimates of the probability of the presence of the species that varies from 0 (unsuitable) to 0.99 (best habitat suitability)3. The Random Forest model was trained on 500 decision trees, and we applied cross-validation techniques to assess the model’s performance. To further investigate the relationship between each environmental predictor and the probability of species presence, we generated response curves for top ranked predictor variable. These response curves illustrate how changes in the predictor values influence the predicted probability of species occurrence. The output map for the average model for the target species was loaded in ArcGIS 10.7.1, where the prediction models of habitat suitability were divided into classes3: Very low or Not suitable (0–0.1), low (> 0.1–0.2), moderate (> 0.2–0.4), high (> 0.4–0.6) and very high (> 0.6) using natural breaks in the symbology tools to produce the habitat suitability model picture3.

Model performance evaluation to assess the performance of the presence/absence model

The spatial validation method was used to evaluate the predictive performance of our model. This involved leave-one-LGA-out cross-validation (i.e., recursively leaving out the data from one LGA, training the model with the data from the other LGAs, and assessing the predictive performance of the model on the left-out LGA, followed by averaging the performance metrics across ten folds). We performed Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis using the ‘pROC’ package. The ROC analysis evaluated the model’s sensitivity and specificity, and we computed the Area Under the Curve (AUC) as a measure of model accuracy. A higher AUC value indicates better discriminatory power (AUC values 0.5 = random to 1 = perfect discrimination) of the model in distinguishing between presence and absence points. Additionally, we computed the root mean of squared residuals a parameter that estimates model accuracy and fitness. The mean of squared residuals and the percentage of variations explained indicate how well the model fits the data. Furthermore, we computed the mean decrease Gini to determine variable importance for the models27.

Study area across the three senatorial districts of Osun State. This figure was created by the authors in Arc GIS software (version 10.7). Available at https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/. The Nigerian shapefile was obtained from World Bank Data Catalog (an Open license standardized resource of boundaries (i.e., state, county) for every country in the world).

Results

Distribution of sibling species of Anopheles gambiae s.l. collected across the study locations

An. coluzzii was the predominant species collected across all the study areas, occurring in approximately 99% of the study sites in each LGAs, while the remaining 1% were An. gambiae s.s. Of the 120 sites visited, 65 were positive for Anopheles species. The site positivity status is shown in Fig. 2a. The number of Anopheles mosquitoes collected ranged from fewer than 2,000 to over 8,000 at different locations within the state (Fig. 2b). Most of the positive breeding sites were located near residential areas (less than 50 m from houses), while most of the negative sites were farther away from human residences (between 100 and 500 m from houses) (Supplementary file). Most of the positive breeding sites were puddles of relatively small to medium size, with rainwater serving as the primary source of water supply. Additional information about the breeding sites can be found in the supplementary file.

Habitat suitability model for Anopheles gambiae species in Osun state

The model predicted a wide range of suitable breeding sites of Anopheles gambiae s.l. in Osun State. The probability range varies from 0.05 (very low or unsuitable) to 0.99 (very high suitability) (Fig. 3a). The results further showed that virtually all areas in the central and, to large extent, the western parts of the state were predicted to be highly suitable for Anopheles mosquito breeding compared to the eastern part of the state (Fig. 3a and b). Only five of the LGAs (Obokun, Ilesa west, Ilesa east, Ife south, Ife north) in the eastern parts have larger areas that were predicted to show very high suitability. All other LGAs in the eastern parts of the state were predicted to demonstrate very low to low suitability with a few pockets of moderate suitability, while more LGAs in the western part of the state have larger areas that were predicted to be highly and moderately suitable for the breeding of Anopheles gambiae s.l. (Fig. 3b).

Model performance and influencing factors

The Mean Decrease Gini of the 23 variables used in modeling the distribution of An. gambiae s.l. in this study were presented in Fig. 4a. The receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve, obtained as an average of the 10 replication runs, is shown in Figure. 4b. The average value of the AUC for the 10 replicate runs was 0.7 for the model. Furthermore, the mean squared residuals (MSR) and the percentage of variation explained by the models are approximately 0.1 and greater than 70%, respectively, for the model. These values indicate a relatively good model performance. An AUC value of 0.7 reflects moderate sensitivity and specificity, while an MSR of less than 0.1 signifies a good model fit, thereby increasing confidence in the models. The plot of the variables’ importance (Fig. 4a) shows that mean diurnal range, mean temperature of the coldest month, elevation, temperature annual range, isothermality, and mean temperature of the coldest quarter were the top six variables that are important and may explain the distribution of An. gambiae s.l. in Osun State (Fig. 4a).

Larval Site Positivity (a) and Number of larvae collected (b) from each site, in Osun State. This figure was created by the authors in Arc GIS software (version 10.7). Available at https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/. The Nigerian shapefile was obtained from World Bank Data Catalog (an Open license standardized resource of boundaries (i.e., state, county) for every country in the world).

Predicted Anopheles larva habitat suitability for Osun Sate (a) habitat suitability unclassified (b) habitat suitability classified. This figure was created by the authors in R programming software (R version 4.1.2, Vienna, Austria). Available at https://www.R-project.org/. The Nigerian shapefile was obtained from World Bank Data Catalog (an Open license standardized resource of boundaries (i.e., state, county) for every country in the world).

Influencing factors that explains the distribution of Anopheles gambiae s.l. in Osun state

The mean diurnal range had the highest contribution with Mean Decrease Gini of 5.2, followed by mean temperature of the coldest month (Mean Decrease Gini of 3.5), elevation (Mean Decrease Gini of 3.2), Temperature annual range (Mean Decrease Gini of 2.9), Isothermality (Mean Decrease Gini of 2.5), and mean temperature of the coldest quarter (Mean Decrease Gini 2.4). The results showed that these variables are strong predictors of An. gambiae s.l. distribution in Osun State (Fig. 4). It is noteworthy to state that temperature ranked higher than precipitation as factors that affect the distribution of these mosquitoes. However, among all the precipitation variables used, precipitation seasonality and precipitation of the wettest month seem to be the most relevant variables that may explain the potential distribution of Anopheles gambiae s.l. in the State (Fig. 4a).

Figure 5 shows the main highest estimated environmental variables (contributions) that determine the distribution of An. gambiae s.l. in Osun State. Spatial analysis was conducted to determine the geographical variability regarding the selected environmental variables in the country. The ranges for the top six environmental variables are presented in Fig. 5a. The response curves of the six variables and the two important precipitation variables to the species’ habitat suitability are shown in Fig. 5b. These curves demonstrate that a mean diurnal range between 9.5 and 10 °C favors the potential distribution of An. gambiae s.l. Furthermore, lower mean temperature of the coldest month values between 18 and 19 °C significantly and potentially favor their distribution (potential distribution decreases with an increase in temperature of the coldest month), while areas with high elevation seem to potentially favor their distribution (Fig. 5b). Their potential distribution seems to increase with the annual temperature range (13.8 to 15 °C potentially favors their distribution), isothermality (66 to 69 °C) potentially favors their distribution), mean temperature of the coldest quarter (24.5 to 25 °C potentially favors their distribution), precipitation seasonality (67.5 to 70 mm potentially favors their distribution), and precipitation of the wettest month (215 to 240 mm potentially favors their distribution) (Fig. 5b).

Estimates of the highest contributing variables that determines the geographical distribution of An. gambiae (a) The highest environmental variables that estimate to control the geographical distribution in Nigeria. (b) Response curves of six temperature and two precipitation predictors used in Random Forest model for An. gambiae. This figure was created by the authors in R programming software (R version 4.1.2, Vienna, Austria). Available at https://www.R-project.org/. The Nigerian shapefile was obtained from World Bank Data Catalog (an Open license standardized resource of boundaries (i.e., state, county) for every country in the world.

Discussion

In this study, we presented model-based estimates of distribution of major malaria vectors in Osun State to aid policymakers and programmers in decision-making towards malaria vector control, which is crucial in the fight against malaria. The sampling locations have a fair representation across the three senatorial districts of Osun State. It is noteworthy to observe an extremely high proportion of An. coluzzii across all the study LGAs indicating that the species is the major malaria vector in Osun State. Earlier reports from other studies in Osun State28,29, and Nigeria4,30,31 reported dominance of An. gambiae s.s. over other members of the gambiae complex. Even then, it is not unlikely that An. coluzzii was the main vector as it was previously known as M-Form of An. gambiae s.s. until recently when it occupied a sibling species status30,31. Unfortunately, only few of the previous studies analyzed the An. gambiae s.s into M and S forms.

The dominance of An. coluzzii across the state may be attributed to its ability to withstand ecological stress, coupled with the effects of climate change3,32. This observation has serious epidemiological implications in the transmission of malaria in the state due to high vectorial capacity and dynamic behaviour3,33,]. For instance, An. coluzziii has been known as efficient vector of Plasmodium malariae in addition to P. falciparium and P. ovale33. Recent studies in Benin Republic also implicated An. coluzziii of higher involvent in malaria transmission as compared with An. gambiae s.s.33. These findings justify the need for active vector surveillance in providing adequate information to control programmers and policymakers.

Our model results suggest that the members of Anopheles gambiae s.l. (specifically An. gambiae s.s. and An. coluzzii) might be widespread across all the three senatorial districts (from high to moderate), with more areas in the central parts of the state being potentially and highly suitable for these species. Species distribution, including mosquitoes, is a function of the relationship that exists between factors such as climate, landforms, soil types and the human settlement patterns in different ecological zones34,35. However, our work is restricted to examining effect of climatic and topographic factors on the distribution pattern of major malaria vector in Osun State. Temperature-related climatic conditions seem to be ranked higher as a major variable contributing to the distribution of these species in the state. This is quite expected, as ambient temperature is crucial to the survival and development of arthropods, and their distribution range is often limited by temperature36.

The monthly temperature, including mean diurnal range (monthly temperature fluctuation) and temperature of the coldest month seems to be strongly associated with the presence of these species. The annual monthly temperature fluctuation in Nigeria is between 6 and 17 °C3, while that of Osun State ranged from 8 to 10 °C indicating a relatively lower range compared to some other states in the country. However, our response curves suggested areas with higher monthly temperature fluctuations in the State (between 9 and 10 °C) to support the breeding of An. coluzzii, and they are likely to be abundant in areas with lower temperature during the coldest month (rainy season) of the year (between 18–19 °C). A study also reported that malaria transmission is high in areas with high temperature fluctuations (between 6 to 11 °C)37. Understanding how temperature affects the distribution of Anopheles mosquitoes is complex; studies have shown that while higher temperature (above 30 °C) may speed up the development of mosquito immature stages, it often leads to low survival rates38,39. This may explain the reasons for the lower temperature in the wet season (with higher temperature fluctuations) serving as major factors influencing their distribution in Osun State.

Another outcome in our model is that elevation emerged as the third highly ranked variable contributing to the distribution of Anopheles species in Osun State, and the mosqutioes were predicted to be more present in highly elevated areas of the State. More recently, evidences that climate change is promoting the emergence and re-emergence of vector-borne diseases (VBDs) are now emerging40,41. It has been reported that climate change alters the life cycles of pathogens and vectors, expanding their geographical distributions, and changing the dynamics of disease transmission. Moreover, previous studies have suggested that the spatial distribution of malaria, which is transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes, has shifted toward higher elevations42 and that the length of its transmission season has increased in highland regions43,44.

Rainfall pattern is one of the important variables that determines the abundance of Anopheles mosquitoes. It has been reported that risk of malaria transmission can also be heightened by rainfall, as it increases the availability and productivity (conditional on ambient temperatures) of mosquito breeding sites45,46. Our model revealed that the precipitation of the wettest month and precipitation seasonality were the highest-ranking precipitation factors in this analysis. In Osun State, the precipitation of the coldest month ranged from 200 to 240 mm, indicating low to moderate precipitation in the wettest month across the state. This is very low compared to other states in Nigeria, where precipitation levels during the wettest month can exceed 3000 mm, particularly in the northern part of the country. Our model suggests that this low range of precipitation during the wettest month, observed across Osun State, supports the breeding and survival of Anopheles species, provided that the required temperature conditions are met. This is in agreement with another study which reported that excess rainfall can lead to the flushing out of Anopheles breeding sites47, thereby reducing the mosquito population.

These findings further buttress the importance of environmental factors, particularly climate and topography, in designing and implementing malaria control strategies in Osun State. When policy makers and implementers are equipped with information on distributional patterns and environmental preferences of Anopheles species in the State, it becomes relatively easier to target when and where to deploy interventions. Some of these interventions include insecticide-treated bed nets, indoor residual spraying, and larval source management, especially to the areas most at risk3. For instance, larviciding in areas where there is a wide range of monthly temperature variations and lower temperatures during the rainy season (coldest month of the year, i.e. mostly in the first to second week of August in Nigeria) will help in targeting the dominant malaria vector species in Osun State with high precision. Therefore, monitoring and adapting control efforts in response to environmental variability and vector behavior can promote the effectiveness of malaria control efforts3 in Osun State and other similar settings.

This work, however, has limitations. One of the limitations of this study is that the model did not consider anthropogenic factors, physciochemical properties of breeding sites (e.g. pH, dissolved oxygen, total dissolved solids, electrical conductivity, and turbidity), land use, soil temperature and pH, presence of cattle and human population density in our model. These variables are also important, and may contribute to explaining species distribution3. Therefore, our future work will incorporate these factors into our study design and evaluate their effects on distribution of Anopheles mosquitoes in the entire State.

For the first time, we have been able to predict the potential distribution of Anopheles gambiae s.l. across Osun State using data from standardized and uniform method of larval collection, employing the Random Forest modeling algorithm.

Conclusion

We have generated a model-based baseline species distribution of the major malaria vector population in Osun State. Knowing that country-wide mapping of vector distribution can be time-consuming and expensive, the maps presented here could be used by the State Malaria Program and other major stakeholders to allocate resources for vector control.

Data availability

The data sets in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World health organization

- LLIN:

-

Long Lasting Insecticidal Net

- IRS:

-

Indoor residual spraying

- LSM:

-

Larval source management

- SDM:

-

Species distribution modeling

- CDC:

-

Centers for disease control and prevention

- PCR:

-

Polymerize chain reaction

- LGA:

-

Local government area

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristics

- AUC:

-

Area under curve

- SRTM:

-

Shuttle radar topography mission

- GIS:

-

Geographic information system

- GPS:

-

Global positioning system

References

World malaria report 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO (World Health Organization, 2022).

World malaria report 2023. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO (World Health Organization, 2022).

Adeogun, A. et al. Spatial distribution and ecological niche modeling of geographical spread of Anopheles gambiae s.l. in Nigeria using real time data. Sci. Rep. 13, 13679. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40929-5 (2023).

Awolola, T. S., Oyewole, I. O., Koekemoer, L. L. & Coetzee, M. Identification of three members of An. funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) group and their role in malaria transmission in two ecological zones in Nigeria. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 99, 525–531 (2005).

Coetzee, M. et al. Anopheles coluzziii and Anopheles amharicus, new members of the Anopheles Gambiae S.l. Zootaxa 3619, 246–274 (2013).

Rejmánková, E. et al. Ecology of larval habitats. In Anopheles Mosquitoes—New Insights into Malar Vectors (Manguin, S. ed), 397–446 (InTech Open, 2013).

Sinka, M. E. et al. The dominant Anopheles vectors of human malaria in Africa, Europe and the middle East: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic. Parasit. Vectors. 3, 117 (2010).

Hemming-Schroeder, E. et al. Ecological drivers of genetic connectivity for African malaria vectors An. gambiae and An. arabiensis. Sci. Rep. 10, 19946 (2020).

National Malaria Elimination Programme (NMEP). [Nigeria], National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria], and ICF. 2022. Nigeria Malaria Indicator Survey 2021 Final Report. (NMEP, NPC, and ICF, 2022).

Blaustein, L. & Kotler, B. P. Oviposition habitat selection by the mosquito, Culiseta longiareolata: effects of conspecifics, food and green Toad tadpoles. Ecol. Entomol. 18 (2), 104–108 (1993).

Escobar, L. et al. Declining prevalence of disease vectors under climate change. Sci. Rep. 6, 39150 (2016).

Omar, K. et al. Ecological niche modeling for predicting the potential geographical distribution of Aedes species (Diptera: Culicidae): A case study of Enugu state Nigeria. Parasite Epidemiol. Control 15, e00225 (2021).

National Bureau of Statistics. Nigeria Population 2006–2016 Report. https://nigerianstat.gov.ng/download/474 (2016).

WHO. Test procedures for insecticide resistance monitoring in malaria vector mosquitoes. (2016). https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjtzPvi8rr9AhUohv0HHcLaDdYQFnoECAsQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fapps.who.int%2Firis%2Fbitstream%2Fhandle%2F10665%2F250677%2F9789241511575-eng.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2mfib4euOS-XutiHogtHS6. Accessed 14 Feb 2023.

Gillies, M. T. & Coetzee, M. A Supplement To the Anophelinae of Africa South of the Sahara (Afro-Tropical Region, Vol. 55 (South African Institute for Medical Research, 1987).

Scott, J., Brogdon, W. & Collins, F. Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae s.l. by PCR. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 49, 520–529 (1993).

Phillips, S. J., Anderson, R. P. & Schapire, R. E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 190, 231–259 (2006).

Khafagi, O., Hatab, E. E. & Omar, K. Ecological niche modeling as a tool for conservation planning: suitable habitat for Hypericum Sinaicum in South Sinai. Egypt. Univers. J. Environ. Res. Technol. 2 (6), 515–524 (2013).

Khafagi, O., Hatab, E. E. & Omar, K. Predicting the potential geographical distribution of Nepeta septemcrenata in saint Katherine protectorate, South Sinai, Egypt using maxent. Academ Arena. 3 (7), 45–50 (2011).

Surakat, O. A. et al. Geospatial distribution and predictive modeling of onchocerciasis in Ogun State, Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 18 (3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281624 (2023). e0281624.

Guisan, A., Graham, C. H., Elith, J. & Huettmann, F. The NCEAS species distribution modelling group. Sensitivity of predictive species distribution models to change in grain size. Divers. Distrib. 13, 332–340 (2007).

Pearson, R. G., Raxworthy, C. J., Nakamura, M. & Peterson, A. T. Predicting species distributions from small numbers of occurrence records: A test case using cryptic geckos in Madagascar. J. Biogeogr. 34, 102–117 (2007).

Olabimi, I. O., Ileke, K. D. & Adu, B. W. Potential distribution of the primary malaria vector An. gambiae Giles [Diptera: Culicidae] in Southwest Nigeria under current and future climatic conditions. J. Basic. Appl. Zool. 82, 63 (2021).

Hijmans, R. J., Cameron, S. E., Parra, J. L., Jones, P. G. & Jarvis, A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 1965–1978 (2005).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Segal, M. Machine learning benchmarks and random forest regression. Cent. Bioinf. Mol. Biostat., 1–15 (2004).

Cutler, D. R. et al. Random forests for classification in ecology. Ecology 88, 2783–2792 (2007).

Adeleke, M. A. et al. Molecular Characterization and Insecticide Susceptibility Status of Anopheles gambiae s.l. (Giles, 1902) in Osun State, Southwestern Nigeria. Nigeria J. Entomol. 34, 69–76 (2018).

Oduola, A. O. et al. Entomological and transmission risk indices of malaria vectors in selected communities in Osun State, Nigeria. Anim. Res. Int. 10 (3), 1805–1808 (2013).

N Okorie, P., E McKenzie, F., G Ademowo, O., Bockarie, M. & Kelly-Hope, L. Nigeria an. vector database: an overview of 100 years’ research. PLoS One. 6 (12), e28347 (2011).

Onyabe, D. Y. et al. The distribution of M and S molecular forms of An. Gambiae Nigeria Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 97, 605–608 (2003).

Zoh, D. D. et al. Role of An. gambiae S.s. And An. coluzziii (Diptera: Culicidae) in human malaria transmission in rural areas of Bouaké, in Côte D’Ivoire. J. Med. Entomol. 57 (4), 1254–1261 (2020).

Akogbéto, M. C. et al. Blood feeding behaviour comparison and contribution of An. coluzziii and An. gambiae, two sibling species living in sympatry, to malaria transmission in Alibori and Donga region, Northern Benin, West Africa. Malar. J. 17, 307 (2018).

Moffett, A., Shackelford, N. & Sarkar, S. Malaria in Africa: Vector species’ niche models and relative risk maps. PLoS ONE 2 (9), e824 (2007).

Siteti, M. C., Injete, S. D. & Wanyonyi, W. A. Malaria parasite species prevalence and transmission dynamics at selected sites in the Western highlands of Kenya. CHRISMED J. Health Res. 3, 45–50 (2016).

Afrane, Y. A., Githeko, A. K. & Yan, G. The ecology of Anopheles mosquitoes under climate change: case studies from the effects of environmental changes in East Africa highlands. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1249, 204–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06432.x (2012).

Agusto, F. B., Gumel, A. G. & Parham, P. E. Qualitative assessment of the role of temperature variations on malaria transmission dynamics. J. Biol. Syst. 23 (4), 1550030 (2015).

Bayoh, M. N. & Lindsay, S. W. Temperature-related duration of aquatic stages of the Afrotropical malaria vector mosquito Anopheles Gambiae in the laboratory. Med. Vet. Entomol. 18, 174–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0269-283X.2004.00495.x (2004).

Kirby, M. J. & Lindsay, S. W. Effect of temperature and inter-specific competition on the development and survival of Anopheles Gambiae sensu stricto and An. arabiensis larvae. Acta Trop. 109, 118–123 (2009).

Rocklov, J. & Dubrow, R. Climate change: an enduring challenge for vector-borne disease prevention and control. Nat. Immunol. 21 (5), 479–483 (2020).

Ogden, N. H. & Lindsay, L. R. Effects of climate and climate change on vectors and vector-borne diseases: ticks are different. Trends Parasitol. 32 (8), 646–656 (2016).

Siraj, A. S. et al. Altitudinal changes in malaria incidence in highlands of Ethiopia and Colombia. Science 343 (6175), 1154–1158 (2014).

Caminade, C. et al. Impact of climate change on global malaria distribution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111 (9), 3286–3291 (2014).

Park, J. W. et al. Time trend of malaria in relation to climate variability in Papua new Guinea. Environ. Health Toxicol. 31, e2016003 (2016).

Githeko, A. K. Malaria and climate change: special feature, in Commonwealth Health Ministers’ Update 2009, Commonwealth Secretariat: Pro-Brook Publishing, London, UK (2009).

LeSueur, D. et al. Towards an atlas of malaria risk in africa: first technical report of the mara/arma collaboration (1998). https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/31644/114833.pdf?sequence=1

Paaijmans, K. P. et al. Unexpected high losses of Anopheles Gambiae larvae due to rainfall. PLoS One 2 (11), e1146 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the numerous entomological technicians and mosquito collectors for their efforts during the state-wide mosquito breeding sites sampling. We want to appreciate the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation for supporting S.A Babalola and T.A Adekunle on Geo-computation and species distribution modeling using Random Forest approach.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization : M.A.A, A.S.B and L.O.B Data Curation: A.S.B, T.A.A and Y.A.A Mapping, geospatial modeling and visualization: A.S.B and T.A.A Investigation: M.A.A, O.A.S, A.M.R, K.A.F, A.A Writing original draft: A.S.B and M.A.A Resources, review and editing: M.A.A, A.S.B, L.O.B, O.A.S, A.M.R, K.A.F, T.A.A, Y.A.A, A.A and G.O Supervision: M.A.A, O.A.s, A.M.R, K.A.F, A.A and G.O Project administration: M.A.A, A.S.B, L.O.B, O.A.S, A.M.R, K.A.F, T.A.A, Y.A.A, A.A and G.O.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adeleke, M.A., Babalola, A.S., Busari, L.O. et al. Modelling species distribution of Anopheles gambiae s.l. in Osun state using random forest modeling approach. Sci Rep 15, 16524 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95001-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95001-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Spatial distribution and insecticide resistance of Aedes mosquitoes in Osun State: implications for vector control

Tropical Medicine and Health (2025)