Abstract

Pseudoexfoliation (PEX) syndrome is a systemic disorder characterized by the accumulation of fibrillar material in ocular and extraocular tissues, primarily affecting the eye’s anterior segment. While PEX is a known risk factor for open-angle glaucoma, its impact on retinal structures is less understood. This study aims to evaluate macular, circumpapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (cRNFL), and choroidal thickness in PEX patients without glaucoma. This cross-sectional study involved two groups: PEX group and a control group, both without glaucoma damage and with intraocular pressure (IOP) below 19 mmHg. Participants underwent full ophthalmic evaluations. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) was used to measure cRNFL, macular, Bruch’s membrane opening-minimum rim width (BMO-MRW), and choroidal thickness. A total of 60 eyes were included: 38 with PEX and 22 controls. Demographic and clinical characteristics were similar across groups. PEX group had a thinner nasal-inferior cRNFL compared to the control group (p < 0.05). Furthermore, PEX group exhibited significantly reduced thickness in superior, inferior, nasal-inferior, nasal-superior, and total ganglion cell layer (GCL), as well as in nasal-inferior, nasal-superior, and total inner plexiform layer (IPL) compared to the control group (p < 0.05). BMO-MRW thickness tended to be thinner across all sectors in PEX group, although no significant differences were found (p > 0.05). Regarding choroidal thickness, the temporal site was significantly thicker in PEX group (p < 0.05). This study highlights a significant association between PEX syndrome and the thickness reduction of the GCL and IPL, suggesting that these retinal changes could serve as early indicators of glaucoma or reflect broader neurodegenerative processes. Findings also reveal reduced cRNFL thickness in PEX eyes, further supporting the potential for early glaucomatous damage detection. These findings underscore the need for long-term studies to explore PEX-related neurodegeneration and its possible links to broader neurological conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pseudoexfoliation (PEX) syndrome is a complex systemic disorder characterized by the accumulation of fibrillar material affecting both ocular and visceral structures. Within the eye, this syndrome is marked by the deposition of pseudoexfoliative material (PEM) on anterior segment structures bathed by aqueous humor, specifically on the lens, iris, ciliary body, and zonules. These deposits can also accumulate on the corneal endothelium, trabecular meshwork, and within the aqueous humor1,2.

The incidence of PEX increases with age, with unilateral involvement observed in approximately two-thirds of patients1.

The accumulation of PEM also occurs in various extraocular tissues such as the skin, lungs, heart, liver, kidneys, and meninges3. The pathogenesis of these deposits remains unclear. However, previous studies have identified several extracellular matrix components, including fibrillin-1 and fibulin-2, within PEM. The abnormal aggregation of elastic microfibrils in PEX deposits exhibits similarities to the amyloid accumulation observed in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Interestingly, amyloid and alpha-1 antichymotrypsin, a regulator of amyloid formation, have been detected in PEM and in the aqueous humor of patients with PEX4.

Recent research indicates that patients with PEX experience a higher prevalence of brain atrophy and AD. It has been well-documented that individuals with early-stage AD often face impairments in visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, color perception, visual field, and motion detection. Initially, visual disorders in AD were thought to be exclusively due to parietal and primary visual cortex pathology. However, increasing evidence showed that the anterior visual pathway degeneration also plays a role in AD pathology4,5.

While PEX is a well-known risk factor for developing open-angle glaucoma (OAG), its impact on the retinal structure in the absence of glaucoma is less studied6. Recent advancements in spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) have enabled detailed examination of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL), ganglion cell layer (GCL), inner plexiform layer (IPL), Bruch’s membrane opening-minimum rim width (BMO-MRW) and choroid thickness, facilitating a better understanding of PEX’s effects on these structures7,8,9.

Compared to normal eyes, eyes with PEX may show subtle structural changes that can be detected using SD-OCT. These changes include alterations in macular thickness and the thickness of retinal layers such as the RNFL, GCL and IPL1,2.

Bruch’s membrane opening-minimum rim width (BMO-MRW) is a precise anatomical measurement of the neuroretinal rim, determined by measuring the shortest distance from the outer edge of the BMO to the internal limiting membrane (ILM). Research suggests that BMO-MRW offers valuable diagnostic accuracy in detecting glaucomatous damage9. Notably, recent studies indicate that BMO-MRW may exhibit alterations in PEX syndrome patients even before changes are detectable in the circumpapillary RNFL (cRNFL)10.

Furthermore, studies have reported that ocular blood flow may be compromised in PEX, which can manifest as changes in choroid thickness. Enhanced depth imaging OCT (EDI-OCT) can provide valuable information regarding choroid thickness and retinal blood flow, offering insights into the broader impacts of PEX on ocular health1.

In our study, we aimed to evaluate macular, GCL, IPL, cRNFL, BMO-MRW and choroid thickness in patients with PEX syndrome without OAG, compared to healthy controls. By focusing on these parameters, we seek to elucidate the structural changes associated with PEX and their potential implications for ocular health in the absence of glaucomatous damage.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted at the Ophthalmology Department of Unidade Local de Saúde de São João, adhering to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study received approval from the Institutional Ethics Review Board of the Unidade Local de Saúde de São João, Porto, Portugal. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Two groups were formed for the study: the PEX group and the control group, both consisting of individuals with no detectable functional or structural glaucoma damage and intraocular pressure (IOP) consistently below 19 mmHg (< 19 mmHg) across three consecutive visits. These subjects were selected independently from the general outpatient clinic.

Examination protocol

All participants underwent a full ophthalmic examination, including a review of medical history, slit-lamp biomicroscopy of the anterior segment, fundoscopic evaluation under farmacologic mydriasis and Goldmann applanation tonometry. IOP was measured using a calibrated Goldmann applanation tonometer (Haag-Streit, Switzerland) at the slit lamp, with the mean of three readings taken during three consecutive visits at different times of the day, all measured by the same examiner.

Inclusion criteria were best corrected visual acuity of 20/40 or better, refractive error within ± 5 diopters of sphere or ± 2 diopters of cylinder, clear media, and healthy optic discs. Visual acuity was measured using a Snellen chart and converted to logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) equivalents for statistical analysis.

For inclusion in the PEX group, the presence of exfoliative material on the pupil margin or lens capsule during biomicroscopic evaluation was required. If both eyes met the inclusion criteria in the PEX group, two eyes per subject were included; in the control group, one eye per subject was randomly selected if both eyes met the criteria.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria for both groups included a history of ocular hypertension, opaque media, age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy at any stage, previous intraocular surgery (except for cataract surgery performed more than 1 year prior), neurological diseases and abnormal visual field tests. An abnormal visual field test was defined as the presence of three or more adjacent points with a p-value < 5% on the pattern deviation plot, a pattern standard deviation (PSD) with a p-value < 5%, or a glaucoma hemifield test (GHT) result outside normal limits. Additionally, optic discs showing glaucomatous features, such as rim notching, focal or diffuse neuroretinal rim thinning, cup-to-disc ratio asymmetry > 0.2, or disc hemorrhages, were excluded. Additionally, in the PEX group, an asymmetry of 5 μm or more in the cRNFL thickness between the two eyes led to the exclusion of the eye with the thinner cRNFL.

Spectral‑domain optical coherence tomography

After pharmacological mydriasis with tropicamide 0.5%, OCT images were obtained by the same experienced technician using the SD-OCT Glaucoma Module Premium Edition software (Spectralis®, Heidelberg Engineering, Germany).

The cRNFL thickness was assessed using a 12° circular scan (3,5 mm diameter) centered on the BMO, and the results were collected in a 6-sector Garway-Heath based grid—temporal (315–45°), temporal-superior (45–90°), nasal-superior (90–135°), nasal (135–225°), nasal-inferior (225–270°), and temporal-inferior (270–315°). Global and sectorial measurements were collected from each patient.

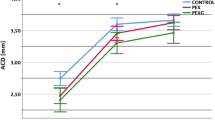

Macular thickness measurements were obtained using the Glaucoma Module Premium Posterior Pole scan software, which employs 61 B-scans spaced 120 μm apart (30° × 25° volume scan) to segment the retina into eight distinct layers. The macula was subsequently analyzed using two classification systems: the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) grid and the 6-sector Garway-Heath-based grid. For this study, the 6-sector Garway-Heath-based grid was recorded. The 6-sector Garway-Heath-based grid utilizes the Anatomic Positioning System (APS) software to align the macula according to the Bruch’s membrane opening (BMO)–fovea axis. It segments the macula into the three ganglion cell complex layers: the retinal nerve fiber layer (mRNFL), the ganglion cell layer (GCL), and the inner plexiform layer (IPL). The macula is then divided into six sectors: superior, temporal-superior, temporal-inferior, inferior, nasal-inferior, and nasal-superior (Fig. 1). Global and sector-specific values were collected from each patient.

To assess the BMO-MRW, the pie charts on the commercial reports were used. The pie chart in the BMO-MRW report based upon 24 angularly equidistant radial B-scans and indicates the average thicknesses of BMO-MRW in six sector areas around the optic disc (temporal, superotemporal, superonasal, nasal, inferonasal and inferotemporal).

Choroidal thickness was assessed by EDI-OCT. Each section, comprising an average of 30 scans, was captured within a 15 × 30-degree rectangle centered on the macula. The choroidal thickness was measured as the distance between the outer surface of the hyper-reflective retinal pigment epithelium layer and the hyper-reflective line at the inner scleral border. Scans were taken at the fovea, as well as 1500 μm temporal and 1500 μm nasal to the fovea along a horizontal plane, as depicted in the scan results from two of our patients (Fig. 2). Two different measurements were conducted by the same ophthalmologist, and the mean value was used for analysis. All measurements were taken at the same time of day to minimize the impact of diurnal variations.

All images were reviewed for disc centration, foveal fixation, segmentation errors, and image artifacts. Minor segmentation errors were manually corrected with the device’s built-in software. The analysis did not include SD-OCT scans with major segmentation errors, poor centering, or quality (signal strength < 20 dB). Macular thickness collection was performed by two investigators to guarantee the agreement of the data.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normal distribution of numerical data. Differences in cRNFL, GCL, IPL, BMO-MRW, macular and choroidal thicknesses were evaluated using the independent samples t-test and the Mann–Whitney U-test. The Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables between groups. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Frequencies and percentages were used to describe qualitative variables and quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Results

A total of 60 eyes (38 with PEX and 22 controls) were included in the study. Table 1 compares the demographic and clinical characteristics between the two groups. The proportions of male to female, eye laterality, and lens status were similar between the groups (p > 0.05). Additionally, the mean IOP values and BCVA showed no significant statistical differences between the groups (p > 0.05).

The patient cohort presented the following systemic comorbidities: 23 patients with hyperlipidemia (17 of the PEX group and 6 of control group), 22 with hypertension (15 of the PEX group and 7 of control group), 11 with diabetes mellitus (8 of the PEX group and 3 of control group), 7 with heart disease (5 of the PEX group and 2 of control group), 6 patients with prostatic disease (4 of the PEX group and 2 of control group), 4 with obesity (2 of the PEX group and 2 of control group), 4 with thyroid disease (3 of the PEX group and 1 of control group), 3 PEX patients with sleep apnea, 1 PEX patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), 1 PEX patient with chronic kidney disease and 1 control patient with an autoimmune disease.

cRNFL measurements obtained by SD-OCT showed that the PEX group had a significantly thinner nasal-inferior cRNFL compared to the control group (p < 0.05). Although cRNFL thickness was generally reduced across all sectors in the PEX group, the differences in other sectors were not statistically significant (Table 2).

The PEX group also exhibited significantly thinner superior, inferior, nasal-inferior, nasal-superior, and total GCL thickness, as well as reduced nasal-inferior, nasal-superior, and total IPL thickness compared to the control group (p < 0.05) (Tables 3 and 4). Differences were observed in all other sectors as well, though they were not statistically significant.

In the BMO-MRW evaluation, no significant differences were found between the two groups in any of the analyzed sectors (p > 0.05). However, the BMO-MRW thickness appeared to be thinner across all sectors in the PEX group compared to the control group (Table 5).

Regarding choroidal thickness, the temporal site was significantly thicker in the PEX group compared to the control group (p < 0.05). However, no significant differences were observed between the PEX and control groups in central macular thickness or in subfoveal and nasal site choroidal thickness (Table 6).

Discussion

Our main results show a significant association between PEX syndrome and GCL and IPL thickness reduction. In our study, superior, inferior, nasal-inferior, nasal-superior and total GCL thicknesses and nasal-inferior, nasal-superior, and total IPL thicknesses in PEX eyes were significantly lower than the control group. This indicates that diffuse or focal macular areas could be affected in PEX syndrome. While there were no prominent differences in the remaining sectors of GCL and IPL when evaluated solely, there was a significant reduction in all of them in PEX eyes.

This result can be interpreted in two ways. First, it suggests that GCL and IPL analysis can be more sensitive in the early detection of glaucoma. Previous research with experimental primate glaucoma models indicates that retinal ganglion cell loss within the central 12° of the retina can occur even in the presence of mild glaucomatous damage. The macula, which houses over 50% of all retinal ganglion cells, is a key area for detecting early cell loss and monitoring changes over time due to its high cell density11. Second, it may reflect retinal neurodegeneration associated with neurodegenerative diseases. There is growing evidence of AD pathology in the retina of AD patients, particularly within the GCL. This is supported by the known association between brain atrophy in AD and PEX syndrome, as well as the resemblance between the elastic microfibrils in PEX deposits and the amyloid accumulation seen in AD5,12.

cRNFL thickness tends to decrease in conditions marked by ganglion cell loss, such as glaucoma. Measuring RNFL thickness is crucial for the early diagnosis and monitoring of glaucoma. A reduction in cRNFL thickness, even before visual field defects appear, can indicate potential progression to glaucoma, enabling earlier diagnosis and intervention1,13,14. This method is advantageous over visual field testing due to its ease of use and reduced dependence on patient adherence1. Vergados et al.15 studied RNFL thickness in 110 patients with PEX syndrome and healthy volunteers, finding that RNFL thickness was lower in the PEX group. Similarly, in studies comparing PEX patients with healthy controls, both Cankaya et al.16 and Mohammed et al.17 observed a decrease in RNFL thickness in the PEX group. Yuksel et al.18 compared eyes with PEX to contralateral eyes and to normal control eyes in a study of 40 patients, finding that RNFL thickness was reduced in PEX-affected eyes compared to both contralateral eyes and controls. Rao et al.19 also reported that RNFL thickness was significantly lower in patients with bilateral PEX compared to those with unilateral PEX. In our study, cRNFL thickness was generally reduced across all sectors in the PEX group, although it was only significantly thinner in the nasal-inferior sector, which may suggest early glaucomatous damage in eyes with PEX syndrome, aligning with findings reported in the literature15,16,17,18,19.

Regarding BMO-MRW analysis, research suggests that it may offer diagnostic accuracy in detecting glaucomatous damage, mainly if combined with cRNFL analysis9. Notably, recent studies indicate that BMO-MRW may exhibit alterations in PEX syndrome patients even before changes are detectable in the cRNFL10. In our study, BMO-MRW thickness appeared to be thinner across all sectors in the PEX group compared to the control group, although no significant differences were found between the two groups in any of the analyzed sectors.

The choroid, composed of vascular and connective tissue and supplied by branches of the ophthalmic artery, is integral to maintaining the circulation for the outer retinal layer and retinal pigment epithelium. It also contributes to temperature regulation and the removal of ocular waste20. Choroidal circulation can be influenced by a range of intraocular and extraocular inflammatory and vascular disorders, including choroidal neovascular membrane, Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease, central serous chorioretinopathy, angioid streaks, uveal effusion syndrome, and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, as well as systemic diseases and the use of systemic and topical medications21,22,23. A reduction in vessel caliber typically manifests as decreased choroidal thickness, which in turn results in functional impairment of the corresponding retinal segments1.

Goktas et al.24 compared 34 patients with PEX to 30 healthy individuals and found a significant thinning in the choroid thickness at subfoveal, nasal and temporal sites 3 mm away from the fovea in the PEX group. This thinning was attributed to increased vascular resistance and decreased blood flow by the authors. Zengin et al.25 compared the choroid thicknesses in 35 patients with PEX syndrome with those in 35 control individuals and found a lower mean choroid thickness in the PEX syndrome group, but the difference was not statistically significant. In a prevalence study of 3022 patients, You et al.26 found no statistically significant correlation between the presence of PEX and the choroid thickness. In our study, choroidal thickness in the temporal site was significantly thicker in the PEX group compared to the control group. This variation from other studies is most likely attributable to the fact that we did not control for the use of medications or the presence of systemic diseases that could influence choroidal thickness. Nevertheless, we opted to include these patients in our sample to ensure a more accurate representation of the general population, particularly given that we are dealing with PEX patients, who are typically older.

It is well established that PEX is a significant independent risk factor for glaucoma, and our findings regarding cRNFL and BMO-MRW align with this understanding and with the current literature6. However, our study provides further evidence of a significant association between PEX and the reduced thickness of the GCL and IPL, offering valuable insights into the pathological impact of PEX, as previously demonstrated by Eltutar et al.2.

Is the reduced thickness of the GCL and IPL attributable to early glaucomatous damage, or is it linked to neurodegenerative processes in the context of an initiating or progressing neurological disease? Could PEX, in the absence of glaucoma, serve as an early marker of neurodegenerative disease in presymptomatic patients?

Study limitations include potential inaccuracies due to IOP fluctuations and the inclusion of both eyes from some subjects, which may affect result validity. While a statistically significant difference in IPL and GCL thickness was observed between PEX patients and controls, these values may still fall within the normal range, as all subjects had normal IOP, and no progressive thinning was detected over the follow-up period. Future research should focus on long-term follow-up to confirm and investigate the mechanisms underlying neurodegeneration in PEX. Furthermore, incorporating brain imaging techniques alongside comprehensive clinical assessments for dementia would significantly enhance our understanding of the interplay between retinal neurodegeneration and PEX.

Conclusion

Our main finding was the significant association between PEX and GCL and IPL thickness, measured by SD-OCT. Based on our results, the nasal sectors of the macula in the GCL and IPL may offer the greatest potential for early screening. However, this hypothesis needs to be tested through sequential studies involving larger populations to assess its clinical utility. Future research should include larger sample sizes and prospectively analyze spatiotemporal changes in OCT measurements to enhance the diagnostic capabilities of retinal imaging in early glaucoma detection and/or the diagnosis of preclinical neurodegenerative diseases.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Demircan, S. et al. The effect of pseudoexfoliation syndrome on the retinal nerve fiber layer and choroid thickness. Semin. Ophthalmol. 32(3), 341–347 (2017).

Eltutar, K., Acar, F., Kayaarasi Ozturker, Z., Unsal, E. & Ozdogan, E. S. Structural changes in pseudoexfoliation syndrome evaluated with spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Curr. Eye Res. 41(4), 513–520 (2016).

Schlotzer-Schrehardt, U. & Naumann, G. O. Ocular and systemic pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 141(5), 921–937 (2006).

Jeong, W. C., Min, J. Y., Kang, T. G. & Bae, H. Association between pseudoexfoliation and Alzheimer’s disease-related brain atrophy. PLoS One 18(6), e0286727 (2023).

Lopez-de-Eguileta, A. et al. Ganglion cell layer thinning in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease defined by amyloid PET. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 5, 570–578 (2019).

Grodum, K., Heijl, A. & Bengtsson, B. Risk of glaucoma in ocular hypertension with and without pseudoexfoliation. Ophthalmology. 112(3), 386–390 (2005).

Bayhan, H. A., Bayhan, S. A. & Can, I. Evaluation of the macular choroidal thickness using spectral optical coherence tomography in pseudoexfoliation glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 25(2), 184–187 (2016).

Budenz, D. L. Symmetry between the right and left eyes of the normal retinal nerve fiber layer measured with optical coherence tomography (an AOS thesis). Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 106, 252–275 (2008).

La Bruna, S. et al. A topographic comparison of OCT minimum rim width (BMO-MRW) and circumpapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (cRNFL) thickness measures in eyes with or suspected glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 29(8), 671–680 (2020).

Azimi, A. et al. Evaluation of the inner macula layers, circumpapillary retinal nerve fiber layer, and minimum rim width thickness in patients with pseudoexfoliation syndrome without glaucoma compared to controls. J. Glaucoma https://doi.org/10.1097/IJG.0000000000002471 (2024).

Desatnik, H., Quigley, H. A. & Glovinsky, Y. Study of central retinal ganglion cell loss in experimental glaucoma in monkey eyes. J. Glaucoma 5(1), 46–53 (1996).

Lopez-de-Eguileta, A. et al. The retinal ganglion cell layer reflects neurodegenerative changes in cognitively unimpaired individuals. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 14(1), 57 (2022).

Palazon-Cabanes, A. et al. Normative database for all retinal layer thicknesses using SD-OCT posterior pole algorithm and the effects of age, gender and axial lenght. J. Clin. Med. 9(10), 3317 (2020).

Pawar, N., Maheshwari, D., Ravindran, M. & Ramakrishnan, R. Interocular symmetry of retinal nerve fiber layer and optic nerve head parameters measured by Cirrus high-definition optical coherence tomography in a normal pediatric population. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 65(10), 955–962 (2017).

Vergados, A. et al. Correlation between optic nerve head parameters, RNFL, and CCT in patients with bilateral pseudoexfoliation using HRT-III. Semin. Ophthalmol. 30(1), 44–52 (2015).

Cankaya, A. B. & Beyazyildiz, E. Scanning laser ophthalmoscopic parameters of eyes with exfoliation syndrome. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 54(4), 300–304 (2010).

Mohamed, M. M. Detection of early glaucomatous damage in pseudo exfoliation syndrome by assessment of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness. Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 16(3), 141–145 (2009).

Yuksel, N., Altintas, O., Celik, M., Ozkan, B. & Caglar, Y. Analysis of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in patients with pseudoexfoliation syndrome using optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmologica 221(5), 299–304 (2007).

Rao, A. Clinical and optical coherence tomography features in unilateral versus bilateral pseudoexfoliation syndrome. J. Ophthalm. Vis. Res. 7(3), 197–202 (2012).

Nickla, D. L. & Wallman, J. The multifunctional choroid. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 29(2), 144–168 (2010).

Yeung, S. C., Park, J. Y., Park, D., You, Y. & Yan, P. The effect of systemic and topical ophthalmic medications on choroidal thickness: A review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 88(6), 2673–2685 (2022).

Nakai, K. et al. Choroidal observations in Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease using high-penetration optical coherence tomography. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 250(7), 1089–1095 (2012).

Koizumi, H., Yamagishi, T., Yamazaki, T., Kawasaki, R. & Kinoshita, S. Subfoveal choroidal thickness in typical age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 249(8), 1123–1128 (2011).

Goktas, S. et al. Choroidal thinning in pseudoexfoliation syndrome detected by enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 24(6), 879–884 (2014).

Zengin, M. O. et al. Choroidal thickness changes in patients with pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Int. Ophthalmol. 35(4), 513–517 (2015).

You, Q. S. et al. Pseudoexfoliation: Normative data and associations—the Beijing eye study 2011. Ophthalmology 120(8), 1551–1558 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This manuscript does not include any nonauthor contributors to acknowledge.

Funding

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ana Faria Pereira (ophthalmologist): conceptualized and designed the study; developed the research methodology; supervised data collection; and drafted the initial manuscript. Pedro Mota Moreira (ophthalmologist): assisted with patient recruitment and data collection; provided clinical expertise and insights; and contributed to manuscript writing and editing. Inês Coelho-Costa (ophthalmologist): assisted with patient recruitment and data collection; provided clinical expertise and insights; and contributed to manuscript writing and editing. Rita Teixeira-Martins (ophthalmologist): assisted with patient recruitment and data collection; provided clinical expertise and insights; and contributed to manuscript writing and editing. Sérgio Estrela (ophthalmologist): managed data entry and quality control; conducted preliminary data analysis; and reviewed the manuscript for accuracy and completeness. Cláudia Oliveira-Ferreira (ophthalmologist): conceptualized and designed the study; provided substantial input on the interpretation of results; and helped with the preparation of the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board of the Unidade Local de Saúde de São João, Porto, Portugal. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study adhered to tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Faria Pereira, A., Mota Moreira, P., Coelho-Costa, I. et al. Retinal neurodegeneration, neuroretinal rim analysis and choroid thickness in pseudoexfoliation syndrome with spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Sci Rep 15, 11576 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95082-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95082-y