Abstract

Landslides are well-known natural or quasi-natural hazards which can harm human lives, infrastructure, and the environment, particularly in mountainous regions like Spiti Valley, Himachal Pradesh, India. The Spiti Valley in Himachal Pradesh, India, is prone to landslides due to its fragile geology, steep slopes, and unpredictable climate. These dangers threaten life, infrastructure, and the environment, requiring comprehensive landslide susceptibility mapping (LSM) for mitigation and planning. Advanced machine learning and new sampling procedures may improve LSM accuracy and reliability in high-risk zones. This investigation aims to enhance LSM through a systematic evaluation of innovative sampling methodologies for non-landslide areas. This study focuses on assessing the effectiveness of two novel sampling methods: Buffer Zone Safe Points (BZSP) and Slope Buffer Safe Points (SBSP). Detailed susceptibility zonation maps were created employing advanced statistical techniques, specifically Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Random Forest (RF), and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), allowing for an in-depth comparison of their predictive performance. The findings clearly indicate the advantages of the SBSP technique, showcasing notable improvements in performance across all metrics. In the analysis of Category-II, XGBoost showed a significant rise in the Area Under Curve (AUC) from 0.91 to 0.97, RF increased from 0.89 to 0.97, and KNN improved from 0.87 to 0.94, with corresponding enhancements in accuracy, sensitivity, kappa values, and F1-scores. These advancements highlight the capability of the SBSP method to enhance susceptibility predictions and reduce overestimation in areas of high vulnerability. The Landslide Density Index (LDI) supports these findings, as Category-II sampling provides more dependable estimates across all susceptibility classes, minimizing variability and improving interpretive confidence. This study emphasizes the essential importance of sophisticated sampling techniques in enhancing the dependability of LSM and establishes a fundamental framework for upcoming research focused on reducing landslide hazards in intricate landscapes. The results highlight the importance of integrating various conditioning factors and flexible approaches to enhance regional hazard evaluations and strengthen disaster readiness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Landslides are significant natural or quasi-natural hazards that occur in hilly mountainous terrains when shear pressure surpasses shear quality in the incline, leading to the downslope movement of rock, soil, or debris due to gravity1. This geo-environmental hazard is observed in mountainous terrains worldwide, triggered by natural processes such as earthquakes and heavy rainfall, as well as human interventions like road cutting, urbanization, and deforestation, which can potentially cause slope failures2. Landslides are classified based on their component material (e.g., rock, debris, soil, or mud) and movement type (e.g., slide, flow, or topple), with triggering factors including natural events like heavy rainfall and earthquakes, and human activities such as road construction and irrigation3. In India, landslides caused significant fatalities, with historical events like the Guwahati landslip in 1948 claiming 500 lives and the Darjeeling landslip in 1968 resulting in over 1000 fatalities4. The Kedarnath landslide in 2013, triggered by heavy rainfall and floods, led to approximately 5700 fatalities and impacted 4200 villages, showcasing the devastating consequences of landslides in the country5. These incidents highlight the destructive nature of landslides in India, resulting in substantial loss of life and extensive damage to infrastructure, emphasizing the need for effective mitigation strategies6. Spiti Valley, located in the Indian Himalayan Region, is a significant area known for its diverse characteristics and susceptibility to landslides7. The valley holds a well-preserved Cambrian formation, the Parahio Formation, which provides insights into early tectonic events in the Himalayas7. The fluvial sedimentary record of the Spiti River highlights its responses to tectonic activity and climatic changes, with periods of aggradation associated with intensified monsoon phases occurring before the Last Glacial Maximum. Furthermore, the sedimentary successions in the Pin and Spiti valleys offer a comprehensive record of the Tethyan Triassic, aiding in understanding global eustatic changes and sequence stratigraphy concepts8. Research in Spiti Valley highlights the habitat drivers influencing the region and the importance of long-term data for environmental conservation. Previous research shows that surface temperature changes in Spiti Valley are significant, and increasing human activities, such as deforestation, further exacerbate the susceptibility of the region to landslides. These factors, combined with the valley’s rugged terrain, make it particularly prone to slope failures7. Given the region’s rugged terrain and geological characteristics, landslide susceptibility (LS) mapping in Spiti Valley is crucial for risk assessment and mitigation8. Various methodologies have been utilized in the field of LS mapping, encompassing fuzzy logic, the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), artificial intelligence (AI), bivariate statistical methods, and machine learning (ML) techniques. Among these approaches, ML methods such as K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Random Forest (RF), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) stand out as the most sophisticated in terms of predictive capabilities9,10.

While bivariate statistical methods serve a purpose, research has shown that they often fall short in predictive accuracy compared to the advanced models of ML11. For instance, studies have demonstrated that ML models, provide higher accuracy and better performance in LS mapping compared to traditional statistical methods12. In contrast, methodologies like fuzzy logic and AHP are essential for handling uncertainties and enabling multi-criteria decision-making13,14,15. However, they lack the predictive precision and scalability of machine learning approaches. Moreover, artificial intelligence techniques, such as neural networks and deep learning, show potential for landslide susceptibility mapping (LSM), although their application in this specific field is still developing1. However, limited research specifically focuses on optimizing non-landslide area sampling strategies in Spiti valley to enhance the performance of ML models for LS mapping11,16.

Landslides represent a critical natural hazard in mountainous areas, such as the Spiti Valley, where the combination of steep slopes, fluctuating climatic conditions, and human activities increases the likelihood of slope failures. Studies on landslide susceptibility (LS) have progressed significantly in recent years, emphasizing the incorporation of various environmental, geological, and hydrological factors. The significant impact of topographical variables on LS mapping, stressing the necessity of scale effects for precise delineation of hazard zones in intricate terrains such as the Sikkim Himalaya17. The rainfall-induced landslides are investigated in the Indo-Nepal-Bhutan Himalayan region, emphasizing the importance of integrating hydrological dynamics into future hazard assessments, especially in areas with significant monsoonal rainfall18.

Additionally, research conducted by19 illustrated how seismic activity can initiate landslides and pinpointed areas in the Sikkim Himalaya that are particularly vulnerable to earthquake-induced landslides, underscoring the importance of geotechnical and seismic elements in susceptibility assessments. Their study on mapping earthquake hotspot and coldspot zones20 offers a significant framework for pinpointing potential landslide-prone areas, highlighting the interaction of tectonic and environmental factors in the Himalayan region. The findings from these studies highlight the importance of tailored, region-specific strategies for LS mapping.

This study tackles the gaps found in existing literature by improving sampling methods for non-landslide regions, with the goal of increasing the precision and dependability of landslide maps. This work enhances our understanding of landslide dynamics by incorporating insights from previous studies and emphasizing the distinct geological and climatic conditions of the Spiti Valley, ultimately advancing risk mitigation strategies in high-altitude terrains. The present study focuses on evaluating various non-landslide area sampling tactics in the context of the Spiti valley to improve the performance of ML models by implementing XGBoost, RF, and KNN for landslide susceptibility mapping. In this region, landslides are influenced by heavy rainfall, seismic activity, and human interventions such as road construction and deforestation. The findings have important implications for disaster management and planning in landslide-prone regions, offering practical guidance for improving landslide prediction and risk mitigation efforts.

Study area

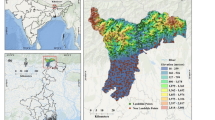

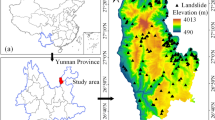

Spiti, located in the northeastern part of Himachal Pradesh, India, is a high-altitude region in the Himalayas. The study area includes the entire Spiti sub-division, which comprises the upper Spiti Valley and extends to Sumdo. The administrative center, Kaza, is situated at 3,650 m elevation on the bank of the Spiti River, while Kyelang in the Lahaul Valley serves as the district headquarters. Spiti and Lahaul are linked by NH-505 through the Kunzum Pass at 4,590 m, which remains snowbound for 5–6 months each year. Spiti sub-division spans 7,252,133,482 square meters with a population of 12,445 according to the 2011 Census. Recognized as a ‘Tribal Area,’ Spiti adheres to the Single-Line Administration system for streamlined communication between local and higher authorities7 (Fig. 1).

The geography of Spiti Valley is marked by steep mountains, deep gorges, and a combination of braided and incised river channels. The Spiti River, originating from the base of the K-111 peak at 6,118 m, flows through the valley and is joined by significant tributaries like the Pin and Lingti rivers.

Elevations in Spiti range from 2,325 m to 6,558 m, with the landscape shifting from wide, braided riverbeds in the upper valley to deeply incised channels and gorges in the lower valley. The cold desert environment of Spiti is characterized by arid conditions due to its location in the rain shadow of the Himalayas7. Spiti Valley lies in a seismically active zone, making it prone to earthquakes6. The region is influenced by the Main Central Thrust (MCT) and the Main Boundary Thrust (MBT), significant fault lines in the Himalayas, leading to frequent seismic activity and increasing the area’s landslide risk. Historical records show several significant earthquakes with epicenters near the MCT and MBT fault zones21. The combination of seismic activity, steep slopes, and loose sedimentary deposits heightens the landslide risk in Spiti6. The region’s geology, characterized by visible sedimentary strata due to sparse vegetation, makes it an excellent site for geological studies. Over time, the Spiti River and its tributaries, such as the Pin and Lingti rivers, have carved deep gorges into the uplifted sedimentary layers. The valley floor comprises ancient sedimentary deposits, with extensive scree slopes along the valley sides. The lower valley’s incised channels and gorges indicate neo tectonic activity in recent geological history7. This complex geological framework underscores the need for detailed landslide susceptibility zonation (LSZ) studies to effectively manage landslide risks and support sustainable development in Spiti Valley.

Materials and methods

The study was divided into two main phases: the initial phase involved data collection and thematic layer formation, while the subsequent phase included data analysis, modeling, and verification of the landslide susceptibility models. The first phase focused on collecting relevant data and creating thematic layers, while the second phase concentrated on analyzing the data, developing models, and ensuring the accuracy of the landslide susceptibility models (Fig. 2).

Data collection and thematic layer creation

The investigation was conducted in two separate stages: the initial phase involved data gathering and the development of thematic layers, which was succeeded by the analysis of data, modeling, and validation of the Landslide Susceptibility Models. The initial phase concentrated on collecting comprehensive data and establishing thematic layers, whereas the subsequent phase encompassed data analysis, model development, and model validation (Fig. 2).

Gathering Data and Developing Thematic Layers.

In the initial phase, data were gathered from multiple sources to create thematic maps of Landslide Conditioning Factors (LCFs), which were essential for comprehending the elements that affect landslide susceptibility. Thematic layers were produced utilizing ArcGIS Pro software. The information in Table 1 outlines the various data types along with their corresponding sources. This study primarily utilized elevation, slope, aspect, NDVI, rainfall, stream density, and various other pertinent environmental factors.

To enhance the precision of the models, two sampling strategies were applied for non-landslide areas:

Buffer Zone Safe Points (BZSP): This approach concentrated on identifying secure locations within buffer zones surrounding identified landslide regions, guaranteeing that the analysis encompassed both landslide-susceptible and secure areas.

Slope and Buffer Safe Points (SBSP): An advanced sampling methodology that takes into account slope gradients alongside their closeness to buffer zones. This guaranteed that the chosen non-landslide points exhibited diversity and encompassed a broad spectrum of environmental conditions.

The methodologies utilized aimed to guarantee that the training data for the models accurately represented both landslide-prone and safe regions in the Spiti Valley, thereby enhancing the overall precision of the models. This study employed a hybrid ensemble approach for landslide susceptibility mapping, integrating various models to improve the precision of the susceptibility maps. This ensemble method is well-regarded for its capacity to combine various datasets, providing more dependable and resilient predictions.

This study employs an ensemble approach that is informed by multiple pertinent studies. An innovative ensemble method has been presented for evaluating landslide susceptibility, which we utilized in our study to combine data from multiple landslide causative factors (LCFs) and produce detailed susceptibility maps22. An ensemble method was employed for mapping landslide susceptibility in the Sikkim Himalayan region, combining various modeling techniques to attain a high level of predictive accuracy. In this study, a hybrid approach was employed to integrate various spatial datasets, ensuring that the resulting maps accurately represented both topographical and environmental influences23.

The impact of rainfall on landslides in the eastern Himalayas has been examined, employing a blend of machine learning and statistical techniques. Their findings regarding the significance of climate data guided our choice to incorporate rainfall as an essential element in the development of the thematic layer24.

Landslide inventory

Creating a comprehensive LS map necessitates a detailed landslide inventory, which serves as a crucial repository for documenting past landslide events25. For the current study area, 1, 314 landslide locations were identified from various sources, including the Bhukosh-Geological Survey of India (GSI) website and Google Earth images4. These landslide events varied greatly in size, from several tens to several thousands of square meters, and were initially depicted in polygon form in the source data. From these polygonal landslide locations, 1,500 points were randomly chosen to represent a 30 × 30 pixel size, with the distance between these points maintained at a minimum of 100 meters to ensure spatial independence. The points randomly selected within the designated regions were marked as ‘1’ to signify areas that has experience landslides26.

Identifying regions that have not experienced landslides is equally important10, as these areas serve as the negative class in landslide risk assessments and can significantly influence the model’s performance16. Defining these zones accurately ensures the model learns from both landslide occurrences and non-occurrences27. Therefore, two specific strategies were developed for sampling non-landslide areas: Category-I: Buffer Zone Safe Points (BZSP) and Category-II: Slope and Buffer Safe Points (SBSP). Previous landslide history records show that the frequency of landslides in Spiti Valley was higher between slopes of 0 to 20 degrees (Fig. 3a, b). This historical data informed the development of the non-landslide sampling strategies. In Category-I, Buffer Zone Safe Points (BZSP) were identified by selecting random points in regions where the slope was less than 10 degrees and at least 300 m away from previous landslide events. Category-II, Slope and Buffer Safe Points (SBSP), were identified through a process that disregarded the slope angle, yet prioritized their location being a minimum distance of 300 m from past occurrences of landslides (Fig. 4a, b, c). The points chosen at random within the specified regions were denoted as “0”. Raster spatial analysis was used to define the slope and calculate proximity11, ensuring a robust and comprehensive dataset for the landslide susceptibility models.

Thematic layers creation

In the thematic layer creation section, various landslide conditioning factors (LCFs) were developed from multiple data sources28. Landslide occurrences in a region are influenced by diverse factors, including geological, environmental, and human activities13,29. The selection of influencing factors is not governed by fixed criteria, as they often vary depending on the specific conditions and data availability of a given region30. The geo-environmental setting encompasses a location’s physical and environmental conditions, such as topography, geology, hydrology, vegetation, climate, and human activities31. In understanding this, 17 LCFs were chosen from areas with comparable geo-environmental conditions and the research area based on literature that was currently accessible.

The selected LCFs include slope, aspect, elevation, plan curvature (Pln_C), profile curvature (Prf_C), distance from faults (DFF), distance from roads (DFR), normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), rainfall, earthquakes, topographic wetness index (TWI), topographic roughness index (TRI), geomorphological unit (GU), land use land cover (LULC), soil texture (ST), road density (RD), and stream density (SD). Details of these LCFs are provided in Table 1. A geospatial database of these LCFs, with a 30-meter spatial resolution, was prepared using GIS21, utilizing the UTM Zone 43 N projected coordinate system and the WGS 1984 datum.

Slope, aspect, elevation, plan curvature, profile curvature

The digital elevation model (DEM) was used to extract elevation, slope, aspect, Pln_C, and Prf_C (Fig. 5a–e). The slope profile controls the shear force acting on soil or rock mass and water distribution, while aspect affects slope stability by influencing the amount of precipitation and solar radiation received32,33. Plan curvature (Pln_C) and profile curvature (Prf_C) impact surface runoff dispersion and convergence, affecting slope stability.

Topographic wetness index (TWI)

The TWI, calculated using the formula:

Where, AS is the specific contributing area and α is the slope angle, indicates the potential for water accumulation. Higher TWI values suggest areas prone to water saturation and increased landslide risk due to enhanced moisture content34 (Fig. 5f).

Topographic roughness index (TRI)

The Topographic Roughness Index (TRI) assesses terrain ruggedness based on elevation variation. It is calculated as formula as per8.

Where, \(\:{DEM}_{mean}\), \(\:{DEM}_{min}\), and \(\:{DEM}_{max}\) are the mean, minimum, and maximum elevations, respectively. TRI values range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating more rugged terrain, influencing water flow patterns and contributing to localized areas of water accumulation and potential instability35 (Fig. 5g).

Distance from roads (DFR), distance from faults (DFF)

Distances from faults and roads were calculated using the Euclidean Distance tool in ArcGIS Pro 3.3, based on fault data from Bhukosh-GSI and road network data from OpenStreetMap36 (Fig. 5h–i).

Rainfall

Rainfall, representing the climatological condition of a region and playing a vital role in landslides, can saturate soils, increase pore water pressure, and initiate mass movements on steep slopes37,38. Rainfall data spanning from 1990 to 2023 was obtained from the Climatic Research Unit (CRU) (Fig. 5j).

Earthquake

Earthquake data, sourced from the United States Geological Survey (USGS), highlights seismic events (Fig. 5k) that contribute significantly to slope instability by inducing ground shaking and potentially destabilizing already vulnerable terrain39.

Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI)

The NDVI, another crucial factor, signifies vegetation cover and health40. High-resolution Sentinel-2 multispectral images is used to compute it using the following formula as mentioned in40.

Where, NIR and R represent the near-infrared and red bands, respectively (Fig. 5l).

Geomorphological units (GU)

Originating from Bhukosh-GSI, geomorphological units were categorized into several types, including FluOri - Piedmont Alluvial Plain1, GlaOri - Snow Cover2, StrOri - Highly Dissected Hills and Valleys3, and others (Fig. 5m).

Land use land cover (LULC)

LULC, an important factor in LS studies, was extracted from the global LULC map provided by Esri4. The map categorizes the land into various classes: water1, tree2, flooded vegetation3, crop4, built area5, bare ground6, snow/ice7, and rangeland8. Each class has different implications for slope stability, with built areas and bare ground being more prone to landslides due to reduced natural vegetation, while tree and rangeland areas may offer more stability due to better root structure and soil reinforcement (Fig. 5n).

Soil texture (ST)

Soil texture (ST), another LCF, influences the intensity and nature of slope movement by affecting geotechnical properties such as pore water pressure, cohesion, and permeability41. This data was adapted from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) world soil map and includes soil types like loam1 and Unweathered Bedrock (UWB)2 (Fig. 5o).

Stream density (SD)

Stream density (SD) as given in (Fig. 5p) measures the total length of streams per unit area and reflects drainage network complexity38, derived from DEM. Higher SD values indicate a denser drainage network, influencing water flow dynamics and sediment transport, which are critical factors in landslide initiation and propagation42.

Road density (RD)

The road density (RD), indicating the intensity of road networks in an area, can exacerbate landslide risks due to increased human activity and alterations in natural drainage43. The road density for the study area was calculated using the kernel density tool derived from the road network data (Fig. 5q).

Data analysis, modeling and validations

The second phase focused on a detailed analysis, modeling, and validation process utilizing BIM SPSS and R software. The initial steps included identifying relevant landslide conditioning factors through correlation matrix and variance inflation factor (VIF) analyses to address multicollinearity issues. Following this, machine learning algorithms such as XGBoost, Random Forest (RF), and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) were applied to develop models predicting landslide susceptibility. The performance of these models was rigorously evaluated using metrics such as accuracy, precision, kappa coefficient, sensitivity, specificity, F1-score, and AUC-ROC (Area Under Curve-Reciever Operating Curve).

Data analysis

In preparation for model training, it is crucial to address potential multicollinearity issues among the selected LCFs43. Multicollinearity, where input parameters are highly correlated, can skew model outcomes44. Therefore, prior to training, multicollinearity analysis using indicators like Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), Tolerance (T), and Correlation Matrix was conducted using BIM SPSS V29.02.0 software for each category. A VIF value exceeding 10 and tolerance below 0.1 typically signifies significant multicollinearity between LCFs4. These results, crucial for refining the model’s input parameters, are summarized in Table 2. Notably, factors such as distance from streams, stream power index, and stream transport index, which exhibited VIF values exceeding 10, were intentionally excluded from further analysis. Following this refinement, all remaining 17 LCFs demonstrated VIF values below 10, ensuring robustness in model training and accuracy. Detailed correlation matrices for each category are visualized in Fig. 6 (a, b), providing insights into the interrelationships among the LCFs under consideration.

LS modeling

Three machine learning models—XGBoost, RF, and KNN—are employed in this work to examine the comparative susceptibility of landslides. Among them, KNN and RF are among the most widely used machine learning models in the field of landslide susceptibility45. The XGBoost, which is a tree-based boosting algorithm, is also getting traction in recent times46. These models are discussed in detail in the following section.

XGboost Model.

XGBoost, built on gradient-boosted regression tree (GBRT) algorithms, stands out as a robust supervised ensemble machine learning method47. Unlike other boosting techniques, its strength lies in effectively handling vast, sparse datasets and being straightforward to implement4. This approach ensures scalability across diverse scenarios while delivering high performance with minimal computational resources. By integrating multiple classification and regression tree models (CART) through gradient boosting, XGBoost achieves superior model accuracy48. Central to its operation is the minimization of the objective function, which comprises the sum of the loss function and a regularization term, crucial for mitigating overfitting11. Mathematically, the objective function is expressed as follows in Eq. 4.

Where, L represents a differentiable loss function that quantifies the dissimilarity between predicted values, \(\:{\widehat{y}}_{i}^{(t-1)}\) and the actual target values \(\:{y}_{i}\), \(\:{\widehat{y}}_{i}^{(t-1)}\) is the predicted value at the (t − 1)th iteration, \(\:{y}_{i}\) is target values of the ith instance of the tth iteration, \(\:{f}_{t}\left({x}_{i}\right)\) represents the prediction of the th tree in the ensemble for the input xi. \(\:{\Omega\:}\left({f}_{t}\right)\:\) serves as a regularization term that penalizes the complexity of the model, thus controlling overfitting. This penalty term is a function of the weights assigned to each decision tree in the ensemble and is stated in Eq. 5.

Where, \(\:{w}_{J}\) is the optimal weight for the Jth leaf and.

T is the number of leaves in a tree t.

The second-order Taylor approximation can be applied for quick optimization, as in Eq. 6 as per4.

Where, \(\:{g}_{i}\) and \(\:{h}_{i}\) is the first and second derivative of the loss function, respectively. In this study, the XGBoost algorithm is implemented using the xgboost package within the R 3.6.2 environment. The model training process involves tuning several key hyperparameters to enhance performance and mitigate overfitting11. These hyperparameters include the maximum tree depth (max depth), the number of boosting iterations (nrounds), the learning rate (η) or shrinkage, the minimum loss reduction (γ) which controls tree-splitting to prevent overfitting, subsample (which determines the percentage of data used per tree), and L2 regularization. Details of these hyperparameters are outlined in Table 3.

RF model

Random Forest (RF) is an ensemble learning model that operates on the bagging principle, suitable for both regression and classification tasks involving large datasets containing numerical and/or categorical data48. The RF model aggregates predictions from these individual trees through majority voting, effectively combining their decisions41. Key parameters such as the number of variables randomly sampled at each split (mtry) and the number of trees in the forest (ntree) are optimized to minimize the out-of-bag error13. Details regarding the search range and optimal values for these parameters can be found in Table 3.

KNN model

K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) is a straightforward algorithm that performs binary classification based on the k nearest neighboring training elements in an n-dimensional input space. It is characterized as a non-parametric and instance-based method4. The KNN model in this study is implemented using the e1071 package within the R 3.6.2 environment. The primary hyperparameter tuned is the k value (Table 3), with the Euclidean distance metric, optimized using a 10-fold repeated cross-validation method.

Validation of model performance

Following model development, the predictive performance of susceptibility models is evaluated using a dataset containing known landslide data points (true points) that were not exposed to the model during training (testing data). In this study, evaluation metrics include the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, along with several statistical measures such as sensitivity (recall), specificity, accuracy, kappa, and F1-score based on (Eqs. 7–11) viz13,16,36,48,49. Sensitivity assesses the model’s ability to correctly classify landslide pixels relative to all actual landslide occurrences41. Kappa statistics quantify the agreement between predicted and actual classifications in binary scenarios (landslide or non-landslide), serving as a reliability measure where values nearing 1 indicate high reliability46. The F1-score amalgamates sensitivity and precision into a single metric, balancing their contributions through harmonic mean calculation31.

Where,

TP (True Positive): The number of landslides correctly classified by the model.

FN (False Negative): The number of actual landslides mistakenly classified as non-landslides.

FP (False Positive): Non-landslide pixels incorrectly classified as landslides.

TN (True Negative): Non-landslide pixels correctly classified as non-landslides.

The precision can be evaluated as per (Eq. 12) as mentioned in4.

Where, \(\:{P}_{C}\) (Proportion Correct): The proportion of pixels correctly classified, which includes both true positives (TP) and true negatives (TN).

\(\:{P}_{\text{exp\:}}\)(Expected Agreements): The expected agreements based on the model’s predictions.

The ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve is a widely used method to evaluate the performance of landslide susceptibility models40. Sensitivity measures the proportion of actual positives that are correctly identified as such, while specificity measures the proportion of negatives that are correctly identified11. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) is the primary metric used to assess the model’s performance. AUC values range from 0.5 to 1, where higher values indicate better model discrimination and predictive capability13.

Evaluating model reliability

In this study, the testing landslide data was employed to assess the model’s reliability using the Landslide Density Index (LDI). The LDI represents the ratio between the percentage of landslide pixels and the percentage of class pixels in each class on the LS map50. If the LDI value increases from a low to a very high susceptibility class, the LS map is considered reliable. LDI calculations are provided in (Eq. 13) as per28. The reliability of each susceptibility map is confirmed if high and very high susceptibility zones experience more landslide exposure than other zones.

The consistency of the landslide susceptibility map is also crucial, ensuring that the majority of landslide data falls within the high or very high susceptibility classes. This consistency indicates that the LSM effectively captures areas most prone to landslides, ensuring its accuracy and reliability in predicting future landslide-prone regions4.

Result and discussion

The study explored the variable importance of LCFs during the model creation. Models were developed for two categories, Category-I and Category-II, using 70% of the data for training and validated with the remaining 30% for testing. The consistency of susceptibility maps was also assessed using the Landslide Density Index (LDI).

LS maps

This investigation focused on creating Landslide Susceptibility Maps for Spiti Valley by utilizing two types of landslide training data. The examination revealed the crucial topographical and environmental elements affecting landslide susceptibility in the area. The Landslide Susceptibility Maps for both Category-I and Category-II landslides were developed through a thorough evaluation of the significance of different Landslide Causative Factors (LCFs), as demonstrated in Figs. 7(a, b), 8(a, b), and 9(a, b).

Elevation was identified as the primary factor influencing landslide susceptibility in both categories. In Category-I, elevation accounted for 31.81%, 16.07%, and 15.02% across various models, while in Category-II, it represented 35.18% and 14.25% significance in different models. This finding underscores the important influence of elevation on landslide dynamics, especially in mountainous regions, as emphasized by17,19. Slope emerged as a significant element in Category-II, accounting for 12.03% in specific models. This aligns with the observations made by Chowdhuri et al. (2022b), who highlighted the role of slope in initiating landslides as a result of gravitational forces. Alongside elevation and slope, various other factors including aspect, NDVI, rainfall, and stream density demonstrated considerable impact in both categories. Aspect showed significant differences among categories, demonstrating an influence of 4.23% in Category-I and 10.28% in Category-II. The NDVI, reflecting vegetation cover, showcased its significance, especially in Category-I, where it had a notable impact of 7.39%. In Category-II, the contribution of NDVI was 8.99%. The role of vegetation in stabilizing slopes and preventing erosion is crucial, as evidenced by extensive documentation in landslide studies.

Rainfall exhibited a steady yet moderate impact across both categories and all factors, supporting the findings of19 that precipitation is a crucial factor in the initiation of landslides. The findings regarding the moderate impact of rainfall in this study indicate that landslide susceptibility may be heightened by extreme weather events. The influence of stream density was significant in Category-I, especially with notable contributions in specific categories (13.53% for certain models and 11.20% for others). This highlights the crucial influence of water channels on slope stability and the heightened risks of landslides. Additional elements like profile curvature, plan curvature, and proximity to fault lines showed differing degrees of impact, with some factors proving to be more critical in one category compared to another (Fig. 10a, b).

The findings of this study reveal numerous similarities with earlier investigations into landslide susceptibility. The elevation, slope, and stream density as critical factors affecting landslide susceptibility in the Lachung River basin in North Sikkim51.

This study similarly identified elevation and slope as the most significant factors, with stream density also contributing importantly in Category-I. The results underscore the significance of topographic factors in evaluating landslide susceptibility in elevated regions. The influence of climatic factors has been examined on hazard modeling for cultural heritage sites52. This study, while not incorporating future climate scenarios, supports previous findings by demonstrating the persistent impact of rainfall, thereby strengthening the connection between precipitation and landslide events. Integrating future climate projections may improve the predictive capabilities of susceptibility models, offering a more precise representation of landslide risk. The impact of storm rainfall and alterations has been highlighted in land use within the Himalayan region on the susceptibility to landslides24. In alignment with their study, this investigation recognized NDVI as a crucial element in mitigating landslide risks, especially in areas with vegetation. Nonetheless, this study noted a moderate effect of rainfall, which contrasts with their findings. This may be linked to variations in regional rainfall intensity and its interplay with various environmental factors.

This study offers important insights; however, it is essential to acknowledge the limitations that future work should address. The investigation depends on specific input factors, and the accuracy and quality of these data—especially regarding rainfall and stream density—may influence the precision of the susceptibility maps. Incorporating higher-resolution, time-series data on rainfall events into future studies is recommended to enhance accuracy and address dynamic landslide triggers. Furthermore, the emphasis on Spiti Valley in this study restricts the applicability of the findings to other areas that may possess varying geological or climatic characteristics. Future studies may investigate temporal datasets and utilize combined methodologies that incorporate topographic, climatic, and human-related factors for a more comprehensive approach to landslide susceptibility mapping. It is essential to consider soil characteristics and human activities, including deforestation and road construction, as these elements can greatly influence landslide risk and enhance the precision of susceptibility models.

This study plays a crucial role in enhancing the comprehension of landslide susceptibility in Spiti Valley, an area that has experienced limited previous exploration. The analysis emphasizes that elevation and slope are the primary determinants of landslide occurrences, while NDVI and stream density contribute notably to risk reduction. Through a comparative analysis with the current body of literature, it is evident that topographical factors are essential in the mapping of landslide susceptibility. Future investigations ought to incorporate temporal and more comprehensive datasets, along with human and soil variables, to enhance the precision and relevance of landslide susceptibility models, thus enabling more informed land-use planning and risk management approaches.

LS maps performance validation

The prediction performances of the models are evaluated based on the widely used AUC-ROC47,53 as shown in (Fig. 11a, b) and other statistical metrics such as sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, F1-score, and kappa using the testing dataset (30% of the total landslide inventory)27 for both categories. Table 4 presents the results of these statistical metrics for all models.

The kappa index for Category-I models varied between 0.58 (KNN) and 0.63 (XGBoost), suggesting a moderate level of agreement with the observed landslide occurrences. Nonetheless, the implementation of Category-II sampling led to a notable enhancement in kappa values throughout all models, underscoring the efficacy of the SBSP sampling technique in improving landslide susceptibility evaluations. This enhancement corresponds with results from investigations such as54, which indicated that sophisticated sampling techniques significantly boost the dependability of susceptibility models in intricate geological environments. In a similar vein55, highlighted that the integration of advanced sampling techniques enhances the classification accuracy of susceptibility maps. In this study, XGBoost was identified as the most effective model, demonstrating superior metrics, especially in Category-II. In Category-II, XGBoost demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.95, specificity of 0.87, accuracy of 0.92, kappa of 0.83, F1-score of 0.93, and an AUC of 0.97, outperforming all other models in terms of these metrics. The findings align with the results of56, who showed that improved classification methods lead to greater reliability in areas susceptible to landslides. The RF model demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.95, specificity of 0.82, accuracy of 0.90, kappa of 0.79, F1-score of 0.92, and AUC of 0.97. The KNN method demonstrated strong performance in Category-II, with a sensitivity of 0.88, specificity of 0.86, accuracy of 0.87, kappa of 0.73, F1-score of 0.89, and AUC of 0.94, albeit with slightly lower effectiveness relative to the other techniques employed. The performance of Category-I models.

was notably lower in comparison. For instance, XGBoost in Category-I demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.83, specificity of 0.81, accuracy of 0.82, kappa of 0.63, F1-score of 0.85, and AUC of 0.91. The RF model demonstrated sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy values of 0.83, 0.76, and 0.80, respectively. Additionally, it achieved a kappa of 0.59, an F1-score of 0.83, and an AUC of 0.89. The KNN model demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.77, specificity of 0.82, accuracy of 0.79, kappa of 0.58, F1-score of 0.81, and an AUC of 0.87. The findings support previous research, including that of57, which emphasizes the shortcomings of conventional sampling methods in regions characterized by complex geological structures. The SBSP sampling technique in Category-II markedly improved model performance, minimizing uncertainties and yielding more dependable susceptibility maps. The results highlight the importance of implementing sophisticated sampling frameworks to address the shortcomings of traditional methods, a perspective also reflected in the studies conducted by58. This study adds to an expanding collection of findings that support enhanced methods aimed at increasing the accuracy and relevance of landslide susceptibility models.

LS maps reliability assessment

Examining the dependability of LS maps plays a pivotal role in evaluating the accuracy of landslide occurrence predictions made by a model33. Within the scope of this research, it has been observed that LDI values (Table 5) consistently exhibited an upward trend across susceptibility categories from “Low” to “Extremely High” for all maps generated, with the exception of the XGBoost model in Category-I. An interesting anomaly emerged in Category-I, where a lower LDI value of 0.71 was recorded for “High” susceptibility in comparison to “Moderate” susceptibility with a value of 0.90. Nevertheless, this discrepancy was notably rectified in Category-II. Table 5 expands on the spectrum of LDI values, varying from 0.02 to 14.64 for Category-I and 0.07 to 7.00 for Category-II.

Particularly intriguing is the observation that LDI values generally exhibit a decrease in Category-II when contrasted with Category-I for areas categorized as “Extremely High” susceptibility. Nevertheless, there is a noticeable surge in LDI values within the “High” and “Very High” susceptibility classes across all three models. This phenomenon hints at a slight tendency of Category-I to overestimate landslide susceptibility zones, while Category-II showcases enhanced reliability. Consequently, the maps produced through the employment of the Category-II sampling method involving Slope and Buffer Safe Points (SBSP) serve to enhance the dependability of LS maps compared to those generated solely through buffer-based sampling utilizing data from landslide-free zones as shown in (Fig. 12a, b).

Analyzing LS Maps Reliability is crucial to determine if a model is overpredicting or underpredicting landslide occurrences5,33,47. In this study, LDI values (Table 5) consistently increased from “Low” to “Extremely High” susceptibility classes for all generated maps, except for the XGBoost model in Category-I, where the anomaly was observed with a lower LDI (0.71) for the “High” class susceptibility compared to the “Moderate” class (0.90) Susceptibility. But that is significantly improve Category-II.

Table 5 indicates LDI values ranging from 0.02 to 14.64 for Category-I and 0.07 to 7.00 for Category-II. This implies that LDI values are lower in Category-II than in Category-I for “Extremely High” susceptibility. However, in High and Very High Susceptibility class it is significantly increased in all three models. Therefore, Category-I slightly overestimated landslide susceptibility zones, while Category-II demonstrated greater Reliability. Consequently, maps generated using Category-II sampling technique Slope and Buffer Safe Points (SBSP) sampling improve the reliability of LS maps compared to only buffer-based sampling for landslide-free zone data (Fig. 12a, b).

Limitations

The findings of this study show potential; however, it is important to acknowledge several limitations that must be taken into account. The landslide inventory utilized for model testing was confined to a particular geographical area. The study area provides important insights; however, the effectiveness of the models may differ when implemented in other regions characterized by varying geological, climatic, or environmental conditions. Future studies ought to focus on evaluating the models using a broader spectrum of landslide data from various regions to enhance comprehension of their overall applicability and reliability.

Furthermore, although we incorporated essential environmental elements like slope, land cover, and proximity to fault lines, there could be additional significant factors that were overlooked in this study, potentially affecting the precision of predictions. Incorporating extra environmental or temporal factors may enhance the overall understanding of landslide dynamics and potentially lead to better model efficacy. The enhancement noted with the SBSP technique is significant; however, it is crucial to recognize that these sampling methods might not be appropriate for all situations. The success of this approach is contingent upon the accessibility and caliber of data, and its influence may differ across various areas. Consequently, subsequent investigations ought to explore alternative sampling methods to evaluate their efficacy relative to SBSP.

Future scope

Given these findings, subsequent investigations ought to examine the implementation of the models across various geographic regions and utilize larger, more diverse landslide inventories. Exploring the integration of various prediction techniques may lead to improved accuracy. Furthermore, the integration of real-time data and the creation of models capable of adjusting to fluctuating environmental conditions will enhance future studies in landslide prediction. This study’s findings mark a notable progression in predicting landslide susceptibility, showcasing the importance of employing more advanced techniques and refined sampling methods. The advancements made enhance our comprehension of landslide dynamics and facilitate the execution of more precise landslide hazard evaluations, potentially supporting disaster management and mitigation strategies.

Conclusions

This study successfully created landslide susceptibility maps for the Spiti Valley using two types of landslide training data: Buffer Zone Safe Points (BZSP) and Slope and Buffer Safe Points (SBSP). Among the machine learning models employed—XGBoost, Random Forest (RF), and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)—the SBSP sampling technique (Category-II) demonstrated exceptional performance. In Category-II, the XGBoost model demonstrated impressive performance metrics: sensitivity (0.95), specificity (0.87), accuracy (0.92), kappa (0.83), F1-score (0.93), and AUC (0.97), highlighting its capability in effectively pinpointing high-risk areas. The Landslide Density Index (LDI) values further corroborated these findings, demonstrating a steady rise from “Low” to “Extremely High” susceptibility classes in Category-II, suggesting that this method reduces overestimation and improves the dependability of landslide suceptibility maps. Key conditioning factors, including elevation, slope, NDVI, rainfall, and stream density, were identified as crucial predictors in all models, highlighting the necessity of integrating various environmental variables for enhanced accuracy. The methodologies and insights gained from this study extend beyond the geographical confines of the Spiti Valley, providing significant applications for landslide susceptibility mapping in other mountainous areas that share comparable geophysical and environmental characteristics. The combination of the SBSP sampling technique with cutting-edge machine learning models establishes a benchmark for enhancing accuracy and dependability in global hazard mapping. The methodologies hold significant relevance in areas susceptible to landslides, especially in light of climate-induced alterations like heightened rainfall variability and shifts in land use.

The findings significantly enhance the global scientific conversation surrounding natural hazard management, showcasing how machine learning and geospatial technologies can effectively reduce risks linked to landslides. Enhancing the accuracy of landslide susceptibility maps contributes to the protection of lives, infrastructure, and ecosystems, in accordance with the objectives of sustainable development and disaster risk reduction, as highlighted by global initiatives like the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Nonetheless, this study recognizes specific limitations. The dependence on accessible remote sensing data could constrain the depth of analysis, given that data resolution and accuracy may differ across regions. Future investigations ought to concentrate on the integration of higher-resolution datasets, the examination of temporal variations in landslide occurrences, and the inclusion of supplementary conditioning factors, such as soil properties and human influences. Furthermore, studies across different regions could confirm the versatility of the SBSP approach in various terrains and climates.

In summary, this study highlights the essential importance of innovative sampling techniques and machine learning models in enhancing landslide susceptibility mapping. The implications reach far beyond local contexts, providing a solid foundation for assessing landslide hazards on a global scale. This study enhances risk management strategies and informs sustainable land use planning, contributing to a more resilient and adaptive approach to mitigating natural hazards globally.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- LCF:

-

Landslide conditioning factors

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factor

- RF:

-

Random forest

- KNN:

-

K-nearest neighbors

- XGBoost:

-

Extreme gradient boosting

- GBRT:

-

Gradient boosted regression tree

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- LDI:

-

Landslide density index

- NDVI:

-

Normalized difference vegetation index

- DFF:

-

Distance from fault lines

- DFR:

-

Distance from roads

- TWI:

-

Topographic wetness index

- TRI:

-

Terrain ruggedness index

- TP:

-

True positive

- TN:

-

True negative

- FP:

-

False positive

- FN:

-

False negative

- LULC:

-

Land use and land cover

- ST:

-

Stream transport

- GU:

-

Geological units

- RD:

-

Road density

- SD:

-

Stream density

- Prf_C:

-

Profile curvature

- Pln_C:

-

Plan curvature

- η:

-

Learning rate (in XGBoost)

- γ:

-

Minimum loss reduction (in XGBoost)

- AUC-ROC:

-

Area under the curve-receiver operating characteristic

- SBSP:

-

Stratified balanced sampling procedure

- F1-Score:

-

F1 score (harmonic mean of precision and recall)

- Kappa:

-

Kappa index (Cohen’s kappa)

- Sensitivity:

-

Sensitivity (true positive rate)

- Specificity:

-

Specificity (true negative rate)

- Accuracy:

-

Accuracy (overall correct classification rate)

- LSI_Pix:

-

Landslide susceptibility pixels

- LS_T_Pix:

-

Total landslide pixels

- LSI_Pix %:

-

Landslide susceptibility pixels percentage

- LS_T_Pix%:

-

Total landslide pixels percentage

References

Feizizadeh, B., Jankowski, P. & Blaschke, T. A GIS based spatially-explicit sensitivity and uncertainty analysis approach for multi-criteria decision analysis. Comput. Geosci. 64, 81–95 (2014).

Xu, H., He, X., Pradhan, B. & Sheng, D. A pre-trained deep-learning surrogate model for slope stability analysis with Spatial variability. Soils Found. 63 (3), 101321 (2023).

Feizizadeh, B., Shadman Roodposhti, M., Jankowski, P. & Blaschke, T. A GIS-based extended fuzzy multi-criteria evaluation for landslide susceptibility mapping. Comput. Geosci. 73, 208–221 (2014).

Agrawal, N. & Dixit, J. GIS-based landslide susceptibility mapping of the Meghalaya-Shillong plateau region using machine learning algorithms. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82 (5), 170 (2023).

Nandi, A. & Shakoor, A. A GIS-based landslide susceptibility evaluation using bivariate and multivariate statistical analyses. Eng. Geol. 110 (1), 11–20 (2010).

Singh, K. & Kumar, V. Hazard assessment of landslide disaster using information value method and analytical hierarchy process in highly tectonic Chamba region in bosom of himalaya. J. Mt. Sci. 15 (4), 808–824 (2018).

Kumar, P., Husain, A., Singh, R. B. & Kumar, M. Impact of land cover change on land surface temperature: A case study of Spiti Valley. J. Mt. Sci. 15 (8), 1658–1670 (2018).

Nandy, S., Singh, C., Das, K. K., Kingma, N. C. & Kushwaha, S. P. S. Environmental vulnerability assessment of eco-development zone of great Himalayan National park, Himachal Pradesh, India. Ecol. Ind. 57, 182–195 (2015).

Dhakal, D., Abdi, S. O., Singh, K. & Sharma, A. Applications of GIS and remote sensing in highway project: a review. J. Min. Environ. 14 (2), 375–388 (2023).

Wubalem, A. & Meten, M. Landslide susceptibility mapping using information value and logistic regression models in Goncha Siso Eneses area, Northwestern Ethiopia. SN Appl. Sci. 2 (5), 807 (2020).

Agboola, G., Beni, L. H., Elbayoumi, T. & Thompson, G. Optimizing landslide susceptibility mapping using machine learning and Geospatial techniques. Ecol. Inf. 81, 102583 (2024).

Cook, M. E. et al. Investigating slow-moving shallow soil landslides using Sentinel-1 InSAR data in Gisborne, new Zealand. Landslides 20 (2), 427–446 (2023).

Ali, S. A. et al. GIS-based landslide susceptibility modeling: A comparison between fuzzy multi-criteria and machine learning algorithms. Geosci. Front. 12 (2), 857–876 (2021).

Asmare, D. Application and validation of AHP and FR methods for landslide susceptibility mapping around choke mountain, Northwestern Ethiopia. Sci. Afr. 19, e01470 (2023).

Panchal, S. & Shrivastava, A. K. Landslide hazard assessment using analytic hierarchy process (AHP): A case study of National highway 5 in India. Ain Shams Eng. J. 13 (3), 101626 (2022).

Gu, T., Duan, P., Wang, M., Li, J. & Zhang, Y. Effects of non-landslide sampling strategies on machine learning models in landslide susceptibility mapping. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 7201 (2024).

Saha, A., Pal, S. C., Chowdhuri, I., Chakrabortty, R. & Roy, P. Understanding the scale effects of topographical variables on landslide susceptibility mapping in Sikkim himalaya using deep learning approaches. Geocarto Int. 37 (27), 17826–17852 (2022).

Chowdhuri, I. et al. Application of novel framework approach for assessing rainfall induced future landslide hazard to world heritage sites in Indo-Nepal-Bhutan Himalayan region. Geocarto Int. 37 (27), 17742–17776 (2022).

Aladejana, O. O., Oraegbu, A. J. & Fagbohun, B. J. An improved multi-criteria decision analysis approach for watershed soil erosion susceptibility assessment. Geocarto Int. 37 (27), 17853–17889 (2022).

Chowdhuri, I., Pal, S. C., Saha, A., Chakrabortty, R. & Roy, P. Mapping of earthquake hotspot and coldspot zones for identifying potential landslide hotspot areas in the Himalayan region. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 81 (7), 257 (2022).

Sweta, K., Goswami, A., Peethambaran, B., Bahuguna, I. & Rajawat, A. Landslide susceptibility zonation around Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh, India: an artificial intelligence model–based assessment. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 81 (8), 310 (2022).

Chakrabortty, R., Pal, S. C., Roy, P., Saha, A. & Chowdhuri, I. Novel ensemble approach for landslide susceptibility index assessment in a mountainous environment of India. Geocarto Int. 37 (26), 13311–13336 (2022).

Chowdhuri, I. et al. Ensemble approach to develop landslide susceptibility map in landslide dominated Sikkim Himalayan region, India. Environ. Earth Sci. 79, 1–28 (2020).

Majeed, K. F., Salama, E., Elfiki, S. A. & Al-Bakhat, Y. M. Z. Natural radioactivity assessment around the petroleum-producing areas of The-Qar Province, Iraq. Environ. Earth Sci. 80 (2), 64 (2021).

Kamran, M. & Yamamoto, K. Evolution and use of remote sensing in ecological vulnerability assessment: A review. Ecol. Ind. 148, 110099 (2023).

Roy, J. & Saha, S. Ensemble hybrid machine learning methods for gully erosion susceptibility mapping: K-fold cross validation approach. Artif. Intell. Geosci. 3, 28–45 (2022).

Achour, Y. & Pourghasemi, H. R. How do machine learning techniques help in increasing accuracy of landslide susceptibility maps? Geosci. Front. 11 (3), 871–883 (2020).

Wei, R. et al. Combining Spatial response features and machine learning classifiers for landslide susceptibility mapping. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 107, 102681 (2022).

Badola, S., Mishra, V. N., Parkash, S. & Pandey, M. Rule-based fuzzy inference system for landslide susceptibility mapping along National highway 7 in Garhwal Himalayas, India. Quaternary Sci. Adv. 11, 100093 (2023).

Ullah, K., Wang, Y., Fang, Z., Wang, L. & Rahman, M. Multi-hazard susceptibility mapping based on convolutional neural networks. Geosci. Front. 13 (5), 101425 (2022).

Khaliq, A. H. et al. Spatiotemporal landslide susceptibility mapping using machine learning models: A case study from district Hattian Bala, NW Himalaya, Pakistan. Ain Shams Eng. J. 14 (3), 101907 (2023).

Chowdhury, M. S. A review on landslide susceptibility mapping research in Bangladesh. Heliyon (2023).

Das, J., Saha, P., Mitra, R., Alam, A. & Kamruzzaman, M. GIS-based data-driven bivariate statistical models for landslide susceptibility prediction in upper Tista basin, India. Heliyon 9(5) (2023).

Banerjee, P., Ghose, M. K. & Pradhan, R. Analytic hierarchy process and information value method-based landslide susceptibility mapping and vehicle vulnerability assessment along a highway in Sikkim himalaya. Arab. J. Geosci. 11, 1–18 (2018).

Veerappan, R., Negi, A. & Siddan, A. (eds) Landslide Susceptibility Mapping and Comparison Using Frequency Ratio and Analytical Hierarchy Process in Part of NH-58, Uttarakhand, India. Advancing Culture of Living with Landslides: Volume 2 Advances in Landslide Science (Springer, 2017).

Dhungana, G., Ghimire, R., Poudel, R. & Kumal, S. Landslide susceptibility and risk analysis in Benighat rural municipality, Dhading, Nepal. Nat. Hazards Res. 3 (2), 170–185 (2023).

Dahal, R. K. et al. GIS-based weights-of-evidence modelling of rainfall-induced landslides in small catchments for landslide susceptibility mapping. Environ. Geol. 54, 311–324 (2008).

Kamal, A. M., Ahmed, B., Tasnim, S. & Sammonds, P. Assessing rainfall-induced landslide risk in a humanitarian context: the Kutupalong Rohingya camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Nat. Hazards Res. 2 (3), 230–248 (2022).

Shao, X. & Xu, C. Earthquake-induced landslides susceptibility assessment: A review of the state-of-the-art. Nat. Hazards Res. 2 (3), 172–182 (2022).

Ikram, Q. D., Jamalzi, A. R., Hamidi, A. R., Ullah, I. & Shahab, M. Flood risk assessment of the population in Afghanistan: A Spatial analysis of hazard, exposure, and vulnerability. Nat. Hazards Res. 4 (1), 46–55 (2024).

Saha, S., Majumdar, P. & Bera, B. Deep learning and benchmark machine learning based landslide susceptibility investigation, Garhwal himalaya (India). Quaternary Sci. Adv. 10, 100075 (2023).

Zhang, Q., Yu, H., Li, Z., Zhang, G. & Ma, D. T. Assessing potential likelihood and impacts of landslides on transportation network vulnerability. Transp. Res. Part. D: Transp. Environ. 82, 102304 (2020).

Mandal, K., Saha, S. & Mandal, S. Applying deep learning and benchmark machine learning algorithms for landslide susceptibility modelling in Rorachu river basin of Sikkim Himalaya, India. Geosci. Front. 12 (5), 101203 (2021).

Gadtaula, A. & Dhakal, S. Landslide susceptibility mapping using weight of evidence method in Haku, Rasuwa district, Nepal. J. Nepal. Geol. Soc. 58, 163–171 (2019).

Saha, A. & Saha, S. Integrating the artificial intelligence and hybrid machine learning algorithms for improving the accuracy of Spatial prediction of landslide hazards in Kurseong Himalayan region. Artif. Intell. Geosci. 3, 14–27 (2022).

Youssef, A. M. & Pourghasemi, H. R. Landslide susceptibility mapping using machine learning algorithms and comparison of their performance at abha basin, Asir region, Saudi Arabia. Geosci. Front. 12 (2), 639–655 (2021).

Chang, Z. et al. Landslide susceptibility prediction using slope unit-based machine learning models considering the heterogeneity of conditioning factors. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 15 (5), 1127–1143 (2023).

Yuvaraj, R. & Dolui, B. Statistical and machine intelligence based model for landslide susceptibility mapping of Nilgiri district in India. Environ. Challenges. 5, 100211 (2021).

Paryani, S., Neshat, A. & Pradhan, B. Improvement of landslide Spatial modeling using machine learning methods and two Harris Hawks and Bat algorithms. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 24 (3), 845–855 (2021).

Huang, F., Teng, Z., Guo, Z., Catani, F. & Huang, J. Uncertainties of landslide susceptibility prediction: influences of different Spatial resolutions, machine learning models and proportions of training and testing dataset. Rock. Mech. Bull. 2 (1), 100028 (2023).

Pal, S. C. & Chowdhuri, I. GIS-based Spatial prediction of landslide susceptibility using frequency ratio model of Lachung river basin, North Sikkim, India. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1–25 (2019).

Saha, A. et al. Modelling multi-hazard threats to cultural heritage sites and environmental sustainability: the present and future scenarios. J. Clean. Prod. 320, 128713 (2021).

Xu, C. Preparation of earthquake-triggered landslide inventory maps using remote sensing and GIS technologies: principles and case studies. Geosci. Front. 6 (6), 825–836 (2015).

Skuzovatov, S. Nature and (in-) coherent metamorphic evolution of subducted continental crust in the neoproterozoic accretionary collage of SW Mongolia. Geosci. Front. 12 (3), 101097 (2021).

Yalcin, A., Reis, S., Aydinoglu, A. & Yomralioglu, T. A GIS-based comparative study of frequency ratio, analytical hierarchy process, bivariate statistics and logistics regression methods for landslide susceptibility mapping in Trabzon, NE Turkey. Catena 85 (3), 274–287 (2011).

Pradhan, B. & Lee, S. Delineation of landslide hazard areas on Penang Island, Malaysia, by using frequency ratio, logistic regression, and artificial neural network models. Environ. Earth Sci. 60, 1037–1054 (2010).

Guzzetti, F., Galli, M., Reichenbach, P., Ardizzone, F. & Cardinali, M. Landslide hazard assessment in the Collazzone area, Umbria, central Italy. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 6 (1), 115–131 (2006).

Süzen, M. L. & Doyuran, V. A comparison of the GIS based landslide susceptibility assessment methods: multivariate versus bivariate. Environ. Geol. 45, 665–679 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2025R804), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2025R804), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, supported this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.D. has performed all the modelling work and writing the manuscript. K.S. helped in database preparation and overall supervision of the work. K.C.O. helped for finalizing the paper. S.A.S.C. helped to revise the manuscript. A.S. performed the validation part of the study. N.A. helped in revision work of the manuscript. F.I. also helped in the revision of the manuscript. R. performed new amendments in the manuscript and helped in detailed analysis. K.P.A. have thoroughly edited the revised version of the manuscript. Y.M.Y. also helped for Indepth revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dhakal, D., Singh, K., Onyelowe, K.C. et al. Enhancing landslide disaster prediction by evaluating non landslide area sampling in machine learning models for Spiti Valley India. Sci Rep 15, 12242 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95087-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95087-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Machine learning-based global landslide susceptibility analysis: spatiotemporal variability and dominant environmental associations

Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment (2026)

-

National-scale landslide susceptibility and risk mapping of India using a hybrid data-driven approach

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

AHP-based landslide susceptibility assessment along National highway 7 (651.000 KM to 731.000 KM) in India

Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy (2025)

-

Integrating GIS and ensemble learning models to predict landslide-prone zones in Chamoli District, India

Discover Applied Sciences (2025)

-

Demystifying the predictive capability of advanced heterogeneous machine learning ensembles for landslide susceptibility assessment and mapping in the Eastern Himalayan Region, India

Natural Hazards (2025)