Abstract

This study evaluated the adherence of bacteria, calcium, and magnesium to three different ureteral stents after endoscopic surgery for urinary calculi. We randomly assigned 61 patients requiring the insertion of ureteral stents after urinary calculi treatment into three groups: Percuflex with a coating composition of Hydroplus (n = 21); Tria with a coating composition of Percushied (n = 22); and InLay Optima, which had a proprietary pHreeCoat coating (n = 18). All stents were removed and evaluated 1 month after treatment. The primary outcome was biomineral attachment to the ureteral stent. Calcium and magnesium contents were measured using atomic absorption spectrometry after the stent had been vortexed in a solution of saline and hydrochloric acid at pH 2. Bacteria were measured through flow cytometry of the washing solution collected by decantation after stent fragments had been immersed and vortexed in a saline solution. Median amounts of calcium and magnesium adhered to Percuflex were significantly higher than those adhered to Tria and InLay Optima. The median number of bacteria adhered was also highest in Percuflex compared to that in the other two groups, although without a statistically significant difference. These findings suggest that selecting stents with superior coating materials enhances patient outcomes and reduces stent-related complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urinary calculi affect approximately 10% of the global population and contribute significantly to healthcare challenges due to recurrent pain and infections1,2. In recent years, the adoption of ureteroscopic lithotripsy (URSL) has grown significantly, driven by the increasing prevalence of urolithiasis3. Correspondingly, the use of ureteral stents has also expanded4. These medical devices are now routinely employed not only during endoscopic urinary calculi procedures but also in cases of ureteral strictures resulting from gastrointestinal or gynecological cancers.

Preoperative stenting leads to passive dilation of the ureter, decreasing operative time and reoperation rates in patients with large stone burden and decreasing the risk of acute distention of the renal capsule by irrigation during URSL5,6. Routine postoperative stent placement may ensure smooth passage of stone fragments and prevent ureteral obstruction6. Moreover, ureteral stents play a vital role in managing urinary tract complications by effectively relieving obstructions and facilitating urine flow from the kidneys to the bladder. This intervention can prevent potential kidney damage and alleviate associated symptoms, including the risk of infection.

Despite their clinical benefits, ureteral stents are prone to encrustation, which can lead to severe complications such as infection, stent blockage, and patient discomfort7,8,9. Furthermore, prolonged stent placement could be a risk factor for iatrogenic ureteral stenosis post endoscopic treatment for urolithiasis10. Stent encrustation presents a particularly challenging problem for urologists, as there is currently no consensus on the most effective approach to managing severely encrusted stents. Encrustation is influenced by several factors, including the duration of stent placement, the chemical composition of urine, and patient-specific variables like metabolic conditions9. Studies have identified bacterial colonization and mineral adherence, particularly of calcium and magnesium, as primary contributors to stent encrustation. Research has demonstrated that bacterial biofilms develop on the stent surface, serving as critical nucleation sites for subsequent mineral deposition9,11,12.

While new biomaterials and coatings have been designed to overcome these disadvantages, there remains a significant gap in the comparative evaluation of different stent materials regarding their susceptibility to bacterial, Ca, and Mg adherence. Furthermore, the long-term outcomes and effectiveness of various stent materials in mitigating encrustation-related complications have not been comprehensively studied, particularly in diverse patient populations. This lack of detailed, comparative data limits our ability to optimize stent design and material choice to reduce encrustation and improve patient outcomes. In this study, we prospectively evaluated the adherence of Ca, Mg, and bacteria to three different ureteral stents after endoscopic surgery for urinary calculi.

Patients and methods

Ethics statement

This study was registered in Japan Registry of clinical Trials (jRCT1042200004) on 21/04/2020 after the approval by Nagoya City University Hospital Clinical Research Review Board. All patients were provided with written informed consent after a thorough explanation of the procedures. This study was conducted between June 2020 to January 2021 in accordance with tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design and participants

This study was a single-center, randomized, single-blind clinical trial comparing biomineral encrustation of three different ureteral stents [group 1: Percuflex stent with a Hydroplus coating (Boston Scientific corporation, Watertown, USA), group 2: Tria stent with a Percushield coating (Boston Scientific corporation), group 3: InLay Optima stent with a pHreeCoat coating (Bard, New Providence, USA)] after endoscopic surgery including flexible-ureteroscopy (fURS) and endoscopic combined intrarenal surgery (ECIRS). The group characteristics are summarized in Fig. 1.

The eligibility criteria were as follows: patients aged between 16 and 85 years; Eastern cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0, 1, or 2; renal and/or upper ureteral calculi, that required treatment via URS or ECIRS. The exclusion criteria were as follows: pregnant or possibly pregnant women, difficult status for general anesthesia judged by an anesthesiologist, and patients with urinary diversion.

Randomization and outcomes

Patients who were planned to undergo fURS or ECIRS were recruited by the outpatient physicians. After informed consent for the study had been confirmed, block randomization was performed through an online computerized software by an independent investigator. Then, each participant was parallelly assigned as 1:1:1 allocation to groups 1, 2, and 3. The results of randomization were first informed to the surgeon during the procedure and were blinded to the patient until the end of the study. Randomization was performed by adjusting for age, sex, positive urinary culture, and surgical procedures (fURS or ECIRS). The flowchart of this study is summarized in Fig. 2.

The primary outcome was the evaluation of biomineral attachment to the ureteral stent including deposits of Ca, Mg, and bacteria. The secondary outcomes were stent encrustation at the time of ureteral stent removal and patients’ ureteral stent symptoms according to the Japanese version of the ureteral stent symptom questionnaire (USSQ)13 at the stent insertion point and on stent removal day. Stone-free status was divided into four categories as follows: completely stone free, 0–2 mm tiny dust, 2–4 mm small fragments, and > 4 mm residual stones on CT at 3 months after surgery. Distal ureteral stent position was evaluated through radiography to determine whether it crossed the bladder midline.

Stents were removed under sterile conditions. At first, stents were examined for discoloration and calcifications as visible signs of encrustation. Upon removal, each stent was sectioned into three equal segments for detailed analysis. Ca and Mg contents were measured using atomic absorption spectrometry after the stent had been vortexed in a solution of saline and hydrochloric acid at pH 2 and was subsequently immersed in a refrigerator at 4 °C overnight. Bacteria were measured through flow cytometry of the washing solution collected by decantation after the stent fragments had been immersed and vortexed in a saline solution.

Intervention and surgical technique

All patients underwent fURS and ECIRS performed by experienced urologists in a manner similar to that previously reported14,15. Pre-operative urine cultures were conducted, and antibiotics were changed based on their results. Following the operation, the allocated ureteral stent was inserted. The ureteral stent length was determined by the surgeons. The position of ureteral stent distal curl was determined by surgeons to ensure proper placement. The duration of stent placement was standardized at 4 weeks to clarify effects of each stent in preventing encrustation.

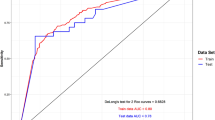

Statistical analysis

The preliminary study of 30 cases demonstrated that Ca attachment to the ureteral stents was 4.85 in Percuflex, 3.36 in Tria, and 2.14 in InLay Optima. We hypothesized that the Tria or InLayOptima stents prevented bacterial attachment more effectively than the Percuflex stent. Therefore, the sample size was calculated with a 0.05 type-1 error, 0.9 power, and 20% superior margin, which resulted in the minimum sample size of 22 for each group.

All statistical analyses were performed using EZR software16. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher exact tests and the Kruskal–Wallis test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using a liner regression model to predict Ca encrustation to the stent and to influence the USSQ urinary symptom index. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

In total, 61 patients (group 1 = 21, group 2 = 22, group 3 = 18) were enrolled. The median ages at the time of obtaining informed consent were 61.0, 55.5, and 59.0 years in groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Furthermore, 38.1%, 36.4%, and 55.6% of patients underwent fURS in groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. There were no significant differences in preoperative factors regarding patients and stone characteristics in the three groups (Table 1).

Primary outcome

The data of biomineral attachment to ureteral stent is shown in Table 1. The median amount [IQR] of Ca adhered to the stents in group 1 was significantly higher than that in groups 2 and 3 (5.42 [2.28–6.04] vs. 1.92 [0.53–4.48] and 1.98 [0.82–3.36] mg/dL, respectively, p = 0.02). The median amount [IQR] of Mg in group 1 was significantly higher than that in groups 2 and 3 (0.20 [0.16–0.29] vs. 0.07 [0.04–0.21] and 0.05 [0.03–0.18] mg/dL, respectively, p < 0.01). The median number [IQR] of bacteria was also highest in group 1 (45.92 [25.33–171.49] vs. 17.80 [6.49–91.33] and 11.90 [5.93–152.91], respectively, p = 0.17); however, there were no significant differences in bacterial adhesion.

Secondary outcomes

In terms of macroscopic observation, the frequency of stent discoloration was significantly higher in group 1 than in groups 2 and 3 (61.9% vs. 40.9% and 22.2%, respectively, p = 0.04). The incidence of stone encrustation was also higher in group 1 than in groups 2 and 3 (25.0% vs. 13.6% and 0.0%, respectively, p = 0.08); however, there were no significant differences in bacterial adhesion (Table 1). As for the relative USSQ domain, the postoperative urinary symptom score on stent removal day was significantly lower in groups 2 and 3 than in group 1 (25.0 [22.0–29.5] and 22.0 [19.8–26.5] vs. 31.5 [28.2–35.8], respectively; p-value < 0.01). There were no significant differences with regard to other domains including pain symptoms, general health, work performance, and sexual matters (Table 2). Statistical analysis was not performed for the domain of sexual matters due to the small number of respondents.

Associated factors with calcium encrustation on the stent

Post hoc exploratory analyses were performed to analyze factors related to the tendency of Ca encrustation on the stent (Table 3a). The univariate analysis showed that patients with higher pH, small residual fragments, and stent type were the risk factors of Ca encrustation. After adjusting for statistically relevant factors (p-value of < 0.1 in the univariate analysis), preoperative ureteral stenting and stent type were identified as independent risk factors for Ca encrustation on the stent.

Associated factors influencing the USSQ urinary symptom index

The factors influencing the USSQ urinary symptom index were evaluated by linear regression analysis. The univariate analysis showed hypertension and stent type were the factors influencing urinary symptom score. Distal ureteral stent position did not affect the USSQ urinary symptoms. After adjusting for statistically relevant factors, hypertension and stent type were found as independent factors (Table 3b).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to provide significant insights into the effectiveness of different ureteral stent coatings in reducing encrustation and bacterial adherence following endoscopic lithotripsy. Our results revealed that stents with Percushield and pHreeCoat coatings significantly outperformed Hydroplus-coated stents in minimizing Ca and Mg adherence. The stent coating material appears to play a crucial role in biomineral encrustation, potentially impacting patients’ quality of life after ureteral stent insertion.

Ureteral stent encrustation may include the following multi-stage process, involving a complex interplay between biological, chemical, and mechanical factors. First, proteins and ions attach to the stent, forming a membrane called a conditioning film. Then, bacteria adhere via protein receptors, forming biofilms. The biofilm acts as a scaffold for the deposition of urinary material. Once a biofilm is formed, production of urease leads to the formation of ammonia, increasing the pH. Next, Ca and Mg aggregate, forming crystals such as struvite and hydroxyapatite9,17.

The material and surface properties of the stent are also thought to be important factors that influence the extent of encrustation. Hydrophobic surfaces tend to promote bacterial adherence and biofilm formation, whereas hydrophilic surfaces (those treated with hydrophilic coatings that accumulate water in their polymer) reduce bacterial adhesion and subsequent mineral deposition18. Recently, some unique ureteral stents have been developed with technology to prevent stent encrustation, including the Tria and InLay Optima stents. The Tria stent has Percushield technology on the hydrophobic inner lumen and outer surface (Fig. 1), which prevents Ca and Mg attachment. Based on the company’s data from an in vitro study, which analyzed biomineral attachment to ureteral stents with an indwelling time of 2 weeks in artificial urine, the Tria stent had less deposition of Ca and Mg salts compared to competitor stents. The InLay Optima stent has pHreeCoat coating that works as a pH stabilizing solution and inhibits urinary Ca salt accumulation. However, the lack of significant differences in bacterial adherence among the groups, despite numerical differences, suggests that while material coatings can reduce mineral deposits, their impact on bacterial colonization might be less pronounced. This finding is consistent with studies suggesting that while hydrophilic coatings can reduce bacterial adhesion, they do not completely prevent it. Future studies focusing on antimicrobial coatings could provide further insights into reducing bacterial colonization on stents.

In this study, we first clarified if the Percushield and pHreeCoat coating technologies reduced the biomineral attachment more efficiently than the Hydroplus coating in a clinical setting, using an indwelling time of 4 weeks. These technologies may contribute to reduced stent encrustation and stent-related infection by preventing the initial process of encrust formation. On the other hand, Yoshida et al. reported micro-CT analysis at 14 days after insertion and showed that the Tria stent had similar inner and outer encrustation amount to the Polaris Ultra with a HydroPlus coating19. Their results differ slightly from the present study, possibly due to the shorter follow-up period and the fact that they were analyzing the actual calcification rather than biomineral encrustation.

Previous reports have demonstrated that the risk factors for stent encrustation include the urinary pH, bacteriuria, positive urinary culture, and duration of stent indwelling time, along with patient-specific factors9,19,20. Our study revealed preoperative ureteral stenting and Hydroplus-coated stents as independent risk factors for Ca attachments after endoscopic surgeries. This study may be the first to show the possible interaction between the differences in stent coating and stent Ca encrustation. On the other hand, there were no significant differences regarding positive urinary culture. Preoperative antibiotics might contribute to decreasing the postoperative infection associated with ureteral stents. The interactions between Ca encrustation and preoperative ureteral stenting have never been reported. Nonetheless, prolonged preoperative ureteral stenting contributes to bacterial colonization and proliferation on the stent surface and can result in urinary tract infections following endoscopic surgeries21. This biofilm formation might be a risk factor for Ca encrustation.

In this study, the USSQ domain scores were evaluated among the three groups. The urinary symptom score was significantly worse in group 1 than the other groups. Multivariate analysis revealed that stent type was an independent factor influencing urinary symptom score. A previous study comparing the USSQ scores between the Percuflex and soft-tipped Polaris stents demonstrated that there were significant differences in terms of voiding symptoms, but the soft-tipped Polaris stent had some advantages with respect to pain and physical activities22. In addition, from the randomized study, Joshi et al. concluded that there were no significant differences in the impact on patient quality of life between ureteral stents composed of firm or soft polymers23. Thus, this study is the first to show that stents with specific coatings, including Tria and InLay Optima, improved patients’ quality of life scores for voiding symptoms. The reasons for this result are unclear, but the amount of Ca attachment did not have a direct relationship with the voiding symptom score. The stent material and coating characteristics might have an impact on the voiding symptom score.

This study has some limitations. First, this study was a randomized, single-blind, and single-center analysis, and the majority of participants were patients with Ca stones and few uric-acid or cystine stones. The efficacy of the pHreeCoat coating against uric-acid and cystine stones, which are likely formed in acidic urine, is unknown. Second, as the position of the ureteral stent was decided by the physician, there the possibility that the physician’s technique bias influenced the patients’ USSQ scores. However, the distal ureteral position did not affect the USSQ urinary symptom score in this study. Third, the relatively short duration of stent placement may not capture long-term encrustation patterns. Further multicenter studies with extended follow-up periods are necessary to validate these findings and evaluate the long-term performance of different stent materials. Lastly, the proximal curl section of the stent, for which encrustation might be the most important in clinical situations, was not evaluated individually in this study. In the future, it may be useful to analyze data only for the proximal curl section of each stent.

In conclusion, this randomized study showed that stents with Percushield and pHreeCoat coatings decreased the adherence of Ca and Mg after endoscopic treatment compared to that when using Hydroplus-coated stents. These findings suggest that selecting stents with superior coating materials may enhance patient outcomes and reduce stent-related complications in clinical practice.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chewcharat, A. & Curhan, G. Trends in the prevalence of kidney stones in the united States from 2007 to 2016. Urolithiasis 49, 27–39 (2021).

Abufaraj, M. et al. Prevalence and trends in kidney stone among adults in the USA: analyses of National health and nutrition examination survey 2007–2018 data. Eur. Urol. Focus. 7, 1468–1475 (2021).

Geraghty, R. M., Jones, P. & Somani, B. K. Worldwide trends of urinary stone disease treatment over the last two decades: A systematic review. J. Endourol. 31, 547–556 (2017).

Hiller, S. C. et al. Ureteral stent placement following ureteroscopy increases emergency department visits in a statewide surgical collaborative. J. Urol. 205, 1710–1717 (2021).

Shields, J. M., Bird, V. G., Graves, R. & Gómez-Marín, O. Impact of preoperative ureteral stenting on outcome of ureteroscopic treatment for urinary lithiasis. J. Urol. 182, 2768–2774 (2009).

Chew, B. H. & Seitz, C. Impact of ureteral stenting in ureteroscopy. Curr. Opin. Urol. 26, 76–80 (2016).

Geavlete, P. et al. Ureteral stent complications—experience on 50,000 procedures. J. Med. Life. 14, 769–775 (2021).

Chew, B. H. & Lange, D. Ureteral stent symptoms and complications: a review. J. Urol. 181, 424–430 (2009).

Tomer, N., Garden, E., Small, A. & Palese, M. Ureteral stent encrustation: epidemiology, pathophysiology, management and current technology. J. Urol. 205, 68–77 (2021).

Moretto, S. et al. An international Delphi survey and consensus meeting to define the risk factors for ureteral stricture after endoscopic treatment for urolithiasis. World J. Urol. 42, 412 (2024).

Wollin, T. A., Tieszer, C., Riddell, J. V., Denstedt, J. D. & Reid, G. Bacterial biofilm formation, encrustation, and antibiotic adsorption to ureteral stents indwelling in humans. J. Endourol. 12, 101–111 (1998).

Riedl, C. R. et al. Bacterial colonization of ureteral stents. Eur. Urol. 36, 53–59 (1999).

Matsuzaki, J. et al. Japanese linguistic validation of the ureteral stent symptom questionnaire. Int. J. Urol. 29, 332–336 (2022).

Hamamoto, S. et al. Prospective evaluation and classification of endoscopic findings for ureteral calculi. Sci. Rep. 10, 12292 (2020).

Hamamoto, S. et al. Comparison of the safety and efficacy between the prone split-leg and Galdakao-modified supine Valdivia positions during endoscopic combined intrarenal surgery: a multi-institutional analysis. Int. J. Urol. 28, 1129–1135 (2021).

Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software EZR for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 48, 452–458 (2013).

Mosayyebi, A., Manes, C., Carugo, D. & Somani B.K. Advances in ureteral stent design and materials. Curr. Urol. Rep. 19, 35 (2018).

Moher, D. et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340, c869 (2010).

Yoshida, T. et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating the shortterm results of ureteral stent encrustation in urolithiasis patients undergoing ureteroscopy: microcomputed tomography evaluation. Sci. Rep. 11, 10337 (2021).

Singha, P., Locklin, J. & Handa, H. A review of the recent advances in antimicrobial coatings for urinary catheters. Acta Biomater. 50, 20–40 (2017).

Şahin, M. F. et al. The impact of preoperative ureteral stent duration on retrograde intrarenal surgery results: a rirsearch group study. Urolithiasis 52, 123 (2024).

Park, H. K., Paick, S. H., Kim, H. G., Lho, Y. S. & Bae, S. The impact of ureteral stent type on patient symptoms as determined by the ureteral stent symptom questionnaire: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. J. Endourol. 29, 367–371 (2015).

Joshi, H. B. et al. A prospective randomized single-blind comparison of ureteral stents composed of firm and soft polymer. J. Urol. 174, 2303–2306 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. N. Kasuga for her experimental support for processing stents.

Funding

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan (no. 22K09455), the grants of the Nitto Foundation, and CASIO Science Promotion Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: S.H., I.T., and S.O. Data analysis and interpretation: S.H. and R.C. Data acquisition: R.C., M.I., K.K., R.U., and K.T. Drafting the manuscript: S.H. and R.C. Critical revision of the manuscript for scientific and factual content: K.T., I.T., S.O., C.B., and A.O. Statistical analysis: R.C. Supervision: T.A.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamamoto, S., Chaya, R., Taguchi, K. et al. Ureteral stent biomaterial encrustation after endoscopic lithotripsy: a randomized, single-blind study. Sci Rep 15, 10614 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95095-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95095-7