Abstract

Leakage is the most common issue encountered in earth–rock dam projects, with characteristics of strong concealment in the initial stage and rapid development and significant threat in the later stage. For a rapid and accurate detection of leakage in earth–rock dams, this paper introduces an infrared thermal imaging technology by fully considering the correlation between dam leakage and temperature. The principle behind the application of this technology for the noncontact detection of water leakage in earth–rock dams was expounded. Based on the theory of flow–heat coupling and combined with a numerical simulation test on the leakage detection of earth–rock dams under the effects of varying water heads and water–air temperature differences, the feasibility of the infrared thermal image technology in detecting leakages in these dams was verified, and the infrared image characteristics of leakage outlets in the dam and their influencing rules were thoroughly analyzed. The results showed that the leakage in the earth–rock dam led to low-temperature anomalies in the leakage outlet area. With the increase in the water air temperature difference and water head, these low-temperature anomalies became increasingly evident. The temperature and water head of the leakage outlet showed a decreasing trend that could be characterized by a quadratic polynomial. The infrared images captured by the UAV could vividly and intuitively present the temperature anomalies caused by leakage, manifesting as a temperature stratification phenomenon with low values inside and high values outside. The temperature measurement accuracy of an infrared thermal imager is positively correlated with reflectivity in a linear manner, whereas it is negatively correlated with the detection distance. Additionally, with an increase in the angle between the focal plane of the infrared thermal imager and the normal direction of the soil dam surface, the temperature measurement accuracy decreases. The development of an unmanned aerial vehicle utilizing the proposed technology for leakage detection in earth–rock dams, along with the identification of abnormal temperature fields indicative of leakage on the dam surface, holds significant importance. This technology contributes to the rapid and accurate detection of leakage hazards, ensuring the safety of earth–rock dam engineering projects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

China frequently witnesses catastrophic floods. Earth–rock dams are an important barrier against floods and play an important role in the development of the national economy1. During the flood season, earth–rock dams encounter dangerous situations, threatening the safety of the lives and properties of residents in protected areas. In addition, during the long-term service of dams, due to water-level fluctuations and complex geological and environmental factors, the damage, leakage, and other diseases that arise in the dam can become serious, particularly seepage deformation and leakage-induced damage2,3. Figure 1 shows that during the 2024 flood season, the first line of earth–rock dam in Tuanzhouwan, Huarong County, Hunan Province, breached due to leakage. The leakage problem of earth–rock dams is different from other safety issues. Due to the small amount of leakage in the initial stage, leakages are hidden and difficult to detect by manual inspection4,5. Moreover, leakage areas have a spatiotemporal randomness6, making it difficult to predict their location and specific time of occurrence. Therefore, when a leakage is discovered, the dam is typically in an extremely dangerous state7. Timely detection, accurate identification, and localization of leakage hazards are crucial for ensuring the safe operation of earth–rock dams.

Currently, there are many methods for monitoring earth–rock dams for possible leakages. Conventional leakage monitoring methods mainly rely on pressure-measuring tubes and water-measuring weirs8. These monitoring methods have a low coverage, and if the monitoring location is not appropriately selected, hidden leakage risks can be easily overlooked. Due to the high water content in areas with leakage hazards, these areas may exhibit physical and chemical properties that differ from those of other normal areas9. Based on this characteristic, extensive and in-depth research has been conducted on the detection and identification of leakage areas in earth and rock embankments10, promoting the development of disease detection, identification, and treatment methods for leakage in earth–rock dams. For example, the high-density resistivity method11 is based on determining the electrical characteristics of the medium in question, and leakage hazards are identified based on the low-resistance pattern of the soil and rock media with a high water content. This method has a high measurement accuracy and can be used to simultaneously obtain the resistivity distribution in both the vertical and horizontal directions, making it widely applicable in engineering practice. The transient electromagnetic method12,13,14 is based on utilizing the fact that the intensity of the eddy current generated by a rapidly changing magnetic field in a medium varies under different moisture contents, which can be used to calculate the internal moisture content of the soil; the higher the soil moisture content, the stronger the eddy current field generated. This method can effectively detect potential seepage hazards at a certain depth inside soil and rock embankments. The ground penetrating radar method15,16,17 is based on the high-frequency electromagnetic wave theory and has been used to analyze and study the waveform characteristics of transmission and reception, thereby inferring the location and morphology of leakage hazards. However, due to the high requirements of the above detection methods, they are mostly used during the dry season and are not very practical for the flood season, where frequent disasters occur. Due to the average efficiency and low degree of automation of the above methods, they are less commonly used in extreme weather and emergency situations. In recent years, the distributed fiber-optic temperature-sensing monitoring method18,19 has also been applied to the monitoring of leakage hazards. This method mainly detects abnormal seepage points inside earth–rock dams by monitoring the temperature field, thereby detecting leakage hazards. The advantages of this method are its good time continuity and wide spatial coverage. However, it requires pre-embedding optical fibers in the object to be monitored, and it has a poor applicability for existing old earth–rock dams. Currently, the fiber-optic temperature measurement-related instruments and equipment are relatively expensive, and the rather low monitoring accuracy can easily lead to misjudgment of leakage hazards. Hence, it is necessary to introduce fast and efficient technologies to provide strong support for flood and drought disaster prevention.

Infrared thermography (IRT) is an advanced technology that employs photoelectric techniques to detect specific infrared signals emitted by objects. These signals are then converted into images and graphics that can be visually interpreted by humans, where different colors are used to depict the surface temperature distribution of objects20. The use of the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-based infrared thermal imaging technology for the leakage inspection of earth–rock dams not only allows for a noncontact measurement of the temperature (made possible by the infrared thermal imaging technology) and is not subject to the limitations of time and distance but also fully utilizes the high maneuverability, ease of operation, and complex terrain adaptability of UAVs. Currently, it is widely used in fields such as forest fire prevention21,22, wildlife search and rescue23, and fault detection24,25. In the application of this technology to the leakage detection of earth–rock dams, Bukowska-Belniak et al.26 demonstrated the feasibility of using IRT for detecting dam leakage through model experiments. Chen et al.27 conducted infrared thermal imaging experiments during the dam water storage and collapse processes, highlighting that leakage induces abnormal temperature variations on the dam surface. Zhou et al.28 conducted passive infrared thermal imaging experiments to detect leakage in soil and rock embankments, concluding that afternoon and nighttime are the optimal periods for using IRT to inspect such leakage. Xu et al.29 used UAVs equipped with thermal imaging equipment for dam leakage detection, image recognition, and other technologies to calculate the leakage area. Wang and Peng et al.30,31 observed the temperature distribution patterns on infrared thermal images and have extracted specific temperature values at certain points on the captured infrared images for data analysis; however, the above research has to some extent promote the application of infrared thermal imaging in the identification of earth–rock dam leakages; little attention has been paid to the texture and morphological features of these images.

In this paper, an infrared thermal imaging technology is introduced by fully considering the correlation between the leakage and temperature in earth–rock dams. The basic principle of non-contact leakage detection using infrared thermal imaging is discussed, and the effects of atmospheric transmittance, dam emissivity, wind force, and solar irradiation angle on the detection accuracy are analyzed. Additionally, numerical simulation experiments conducted on infrared thermal imaging for seepage detection in earth–rock dams under varying water heads and temperature differences are presented. The infrared image characteristics and influencing laws of the leakage outlets in the earth–rock dam are thoroughly analyzed, providing a theoretical support for the application of the UAV-based infrared thermal imaging technology in detecting leakages in earth–rock dams.

Infrared thermal imaging leak detection theory

Basic principles

According to Planck’s blackbody radiation law32, when the temperature of an object in nature is above absolute zero (− 273.15 °C), the object can automatically absorb, radiate, and reflect electromagnetic waves. The infrared radiation intensity of a substance is positively correlated with its own temperature, that is, the higher the temperature, the greater the amount of infrared radiation. The above Planck’s blackbody radiation law can be represented by Eq. (1)33:

Here, \(\lambda\)and \(T\) are the electromagnetic wavelength and thermodynamic temperature of the substance, respectively; \(h\) is the Planck’s constant, taking a value of 6.626 × 10−34 J·s; \(k\) is the Boltzmann constant, taking a value of 1.38 × 10−23 J/K; \(c\) is the propagation speed of electromagnetic waves in vacuum, taking a value of 2.998 × 108 m/s.

The specific heat capacity of water (approximately 4.2 × 103 J/kg) differs significantly from that of soil (approximately 0.84 × 103 J/kg), and areas with leakage in soil and rock embankments will exhibit different temperature change patterns from normal areas due to their high moisture content. By scanning and observing with an infrared thermal imager, it can be observed that the slope surface of the earth dam will form temperature zones of different colors. Therefore, the temperature field distribution on the surface of the earth dam can be measured by an infrared thermal imager to determine its leakage state. If the temperature field is abnormal, it is highly likely to be caused by leakage. Follow-up measures will be taken to conduct a secondary screening of the abnormal temperature field area, ultimately achieving identification and localization of the leakage area.

Numerical analysis of flow–heat coupling

Mathematical model

The governing equation, i.e., the Richards equations, for groundwater flow is as follows:

Here, P is the pressure; g is the gravitational acceleration; \(\mu\:\left(T\right)\) is the dynamic viscosity of water, which is a function of the temperature T; \(\rho\) is the density of water, assumed to be constant here; \(\theta\) is the moisture content; \(z\) is the elevation of the leakage point; \({C}_{m}\) is the water capacity; \({k}_{s}\) is the saturation rate of the permeable medium; \({S}_{e}\) is the relative saturation of the soil; \({S}_{s}\) is the elastic water storage rate; \({k}_{r}\:\left(\theta\right)\) is the relative permeability of the unsaturated zone (0 ≤ k_r (θ) ≤ 1), which is a function of the water content \(\theta\); \(\nabla\) is the Laplace operator; \({Q}_{m}\) represents the source and sink term of water flow.

The temperature field is described by the thermal convection heat transfer equation:

Here, T is the ground temperature; \({\lambda}_{{eq}}\) is the equivalent heat transfer coefficient; \({{c}}_{{eq}}\) is the equivalent specific heat capacity; \({\rho}_{{eq}}\) is the equivalent density; \({c}_{w}\) is the specific heat capacity of the water; \({\rho}_{{w}}\) is the density of the water; \({{Q}}_{{s}}\) is the heat source–sink term; and \({u}\) is the average flow rate of the water, which is numerically \(u=v/\theta\).

Basic assumptions

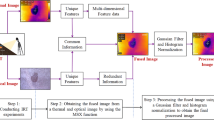

This numerical analysis focuses on the temperature field characteristics of the leakage outlet and solves the problem of rapid identification of the leakage outlet by coupling the seepage field and temperature field of the dam. Due to the seepage effect, it can promote the exchange and transfer of heat inside the dam body, thereby affecting the distribution of the entire dam temperature field. Figure 2 shows the simplified geometric model of dam leakage. In practice, there are many factors that affect the leakage of earth–rock dams, and the degree of influence of each factor is different. The mathematical methods and heat conduction theory used are not unconditional and absolute, they are established under certain conditions and premises. To simplify the solution while reflecting the key elements, the following assumptions and simplifications are made to the model:

-

(1)

The dam body is a homogeneous and isotropic continuous medium, and the seepage is also considered a continuous medium.

-

(2)

The thermal properties of the soil are uniform and do not vary with the soil temperature.

-

(3)

The seepage of the dam body follows Darcy’s law.

Model calculation parameters

When studying the temperature field distribution under different permeability coefficients of the dam body, Zhou et al.34 found that the temperature field is quite evidently affected by the seepage field when the permeability coefficient of the dam body is kd ≥ 5 × 10−5 m/s, and the temperature at each point on the dam body is close to that in the case of no seepage when the permeability coefficient of the dam body is kd ≤ 7 × 10−7 m/s. Wang et al.35 performed a 3D seepage stability analysis of buildings passing through a plain reservoir dam body; the permeability coefficient of the dam body was taken as 10−7 m/s, and the foundation permeability coefficient was taken as 5 × 10−5 m/s. A pressure boundary was set as the boundary condition and applied to the upstream surface, with a normal water storage level of 9 m. To simplify the model and perform calculations effectively, the downstream surface was set as the drainage boundary, and the remaining surfaces were taken as default impermeable boundaries. Referring to the above research results, the permeability coefficient of the normal dam body was fixed at kd = 2.94 × 10−7 m/s, and the permeability coefficient of the leakage channel was kc = 2.94 × 10−3 m/s. Table 1 presents the thermodynamic and physical mechanical parameters of the model dam body and leakage channel materials. Table 2 presents the unsaturated seepage parameters.

Field test

To demonstrate the applicability and reliability of the infrared thermal imaging technology onboard the UAV for dam leakage detection and to provide a theoretical basis and practical reference for the popularization and application of this technology, an experimental study on its application for the leakage identification of earth–rock dams was performed in a test site of earth–rock dams.

Dam leakage survey

Engineering overview

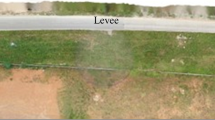

The dam studied herein was composed of a rockfill material located in Heihe City. The rockfill pressure body was set at the upstream and downstream toes of the dam. The length of the dam crest was approximately 385 m, the width of the dam crest was 5 m, the upstream dam slope was 1:1.65, and the downstream dam slopes were 1:1.5 and 1:1.55 from top to bottom. The slope changed at an elevation of 259.40 m, and a 4 m-wide bench berm was set up. Because the dike was built on the spot, the dike body was mainly composed of rockfill, and the miscellaneous fill was distributed locally. Due to the poor filling quality and anti-seepage performance, leakage occurred in the natural state of the downstream dam surface. The temperature of the UAV during the inspection was 12.4 °C, and the water temperature of the dam was 6 °C. Figure 3 shows the site map of the dam captured by the UAV equipped with the infrared thermal imager.

Detection system design

A UAV was equipped with an infrared thermal imager-based detection system, comprising three parts: a UAV platform, an infrared thermal imager, and a ground remote control station. Figure 4 shows the designed detection system. The UAV platform mainly performs two tasks: autonomous flight according to the flight plan and carrying of the infrared thermal imager. The infrared thermal imager was used to capture the thermal image of the downstream surface of the dam. The ground remote control station was responsible for sending control commands, receiving the operating state parameters of the UAV platform and the infrared thermal imager, and displaying the real-time images. Therefore, the DJ 350 RTK UAV and the Zenmuse H20T infrared thermal imager was selected in this study. Table 3 presents their main technical indicators. The UAV platform in a detection system has the advantages of portability, high free hovering accuracy, stable flight, high positioning accuracy, long image transmission distance, and a certain load capacity. To ensure the maneuverability and safety of the UAV, the operation in rainstorms, strong winds, and other complicated climatic conditions should be avoided. The infrared thermal imager in the detection system has high resolution, thus achieving identification of small temperature differences. The DJI GL900 ground remote control station was selected. Its signal transmission distance can reach 8 km, and the transmission signal is strong and stable. A thermometer with a range of 0–30 °C and an accuracy of 0.01 °C was used to measure and record the temperature difference.

Analysis of detection accuracy

The detection of leakage in a dam body from its infrared thermal image involves the use of a UAV equipped with an infrared thermal imager to capture the temperature field on the surface of the dam body. In this method, a possible leakage in the dam body is detected by analyzing the collected data. The infrared image captures the thermal radiation on the surface of the object. To ensure the accuracy of the temperature measurement of the UAV-borne infrared thermal imager, it is necessary to consider the effects of atmospheric transmittance, dam surface emissivity, wind force, and solar irradiation angle36,37.

(1) Atmospheric transmittance

The attenuation of infrared radiation is affected by atmospheric composition, mainly meteorological attenuation, such as carbon dioxide, water vapor, rain, and snow38. Floating particles in the atmosphere absorb infrared rays, which distort the image captured by the infrared thermal imager and cause errors. During rain, snow, or a sandstorm, due to the interference from water vapor and dust, the scattering phenomenon affects the accuracy of the temperature measurement. When using an infrared thermal imager to detect leakage, reducing the temperature measurement distance as much as possible on the basis of ensuring a wide field of view; when shooting, hazy, rainy, and snowy conditions must be avoided, and it is best to test under conditions with a humidity of no more than 75%39.

(2) Dam surface emissivity

The emissivity of a dam surface refers to the strength of the radiation capacity of the dam surface, which is the main factor affecting the temperature measurement accuracy of the infrared thermal imager. The temperature obtained by remote sensing is linearly positively correlated with the reflectance, and the higher the reflectance, the greater the temperature at the measuring point, as shown in Fig. 5. When the reflectivity is below 0.95, the remote sensing temperature of the dam surface will continuously decrease with a decrease in the reflectivity; when the reflectivity is higher than 0.95, as the reflectivity increases, the remote sensing temperature of the dam surface will be higher than the actual true value. The surface emissivity is related to the vegetation coverage, flatness, color, and roughness of the dam surface. A wide coverage of vegetation on the dam surface can decrease its emissivity, and when the dam surface is uneven, the emissivity will increase. The surface emissivity of common materials, such as soil, sand, and water, used in the construction of earth dams is above 0.9. The remote sensing detection of target temperature is done within an error of ± 15% of the actual real temperature, making them ideal infrared detection targets40.

(3) Shooting angle and distance

The angle between the focal plane of the infrared thermal imager and the slope surface of the earth dam can also affect the detection effect. The larger the angle between the focal plane of the infrared thermal imager and the normal direction of the earth dam surface, the lower the temperature measurement accuracy41. In addition, the temperature measurement accuracy of infrared thermal imagers is negatively correlated with the detection distance, as shown in Fig. 6. The farther the detection distance, the lower the temperature detected by the infrared thermal imager will be compared to the actual temperature of the target object, and the relationship between the two satisfies an exponential function. Therefore, close range detection should be ensured as much as possible42.

(4) Wind

The infrared detection of earth–rock dam is performed outdoors, and the wind force will significantly impact the infrared detection results. The greater the wind force, the faster the dissipation of the heat to the defect area of the target object, forming a strong cooling effect, resulting in a lower infrared detection temperature compared with the actual value43. In practical engineering exploration, it is advisable to choose a time period with lower wind speeds, which is also beneficial for maintaining the stability of drone travel and prolonging the travel time.

Results and discussion

Numerical calculation of the model

As the main purpose of this model experiment is to use the image technology to solve the problem of rapid identification of leakage outlets in earth–rock dams, the focus is on the infrared image characteristics and patterns of leakage outlets, and a quantitative analysis of the seepage field inside the dam body is not currently conducted. Therefore, assuming that the dam body is a homogeneous isotropic continuum, ignoring the heterogeneity and layering of the actual dam body filling material can not only simplify the model calculation but also not affect the infrared image characteristics and laws of the leakage outlet.

To investigate the abnormal temperature field on the downstream dam surface caused by dam leakage. Based on the measured operating environment temperature of the dam during the flood season, the dam body temperature was set to 17 °C, the reservoir water temperature to 15 °C, and the atmospheric temperature to 25 °C. As shown in Fig. 7, when the temperature is greater than the reservoir water temperature, and if dam leakage occurs, the seepage field in the dam interacts with the temperature field, the temperature field in the dam changes, and the leakage outlet on the dam surface exhibits a low-temperature anomaly. This is because the earth–rock dam only has seepage phenomenon when there is no leakage, the flow velocity is low and stable, and there is time and space for heat exchange between the soil material and water; therefore, the temperatures of the soil material and water are the same. However, when there is a leakage channel, the flow rate of the water in the channel is accelerated. Compared with the seepage water in the stable seepage period, its temperature is closer to the water temperature at the entrance of the leakage channel. At this time, the temperature difference inevitably produces heat conduction. Due to the flow velocity, the heat exchange between the water and the soil in the channel is incomplete, and heat is exchanged only between the surrounding channel and the earth–rock mass and thereafter advances to the interior regions of the dam. Therefore, the original stable temperature field varies significantly due to the generation of leakage channels, forming a new temperature field. By comparing the temperature field with the original temperature field, the location of the leakage channel can be determined more intuitively.

Effects of water head and water–air temperature difference

Through the coupling analysis of the seepage and temperature fields, the temperature field distribution of the dam surface under various water–air temperature differences and water head was calculated, as listed in Table 4. When air temperature > reservoir water temperature, and there was leakage in the dam, the temperature field on the downstream dam surface of the model dam body exhibited an evident low-temperature anomaly, and the temperature at the outlet point was significantly lower than that of the normal dam body, exhibiting an elliptical low-temperature area. With the increase in the water–air temperature difference, the temperature anomaly of the downstream dam surface was higher, and the greater the water head, the more evident the anomaly of the elliptical low-temperature area. This is because the leakage degree of the dam model was affected by the water head. An increase in the water head strengthens the migration ability of the leakage channel, and the fluid flow rate and leakage amount in the leakage channel will also increase, thus reducing the heat transfer capacity of the dam leakage area. The outlet point of the leakage water was affected by the water temperature, resulting in a temperature drop. The temperature at the water outlet point was lower than that of the surrounding normal dam body, exhibiting a low-temperature anomaly. When the leakage was sufficiently large, the insufficient heat transfer of the soil made the temperature at the water leakage point closer to the water temperature, and the temperature gradient changed more evidently under the action of the water–air temperature difference.

As shown in Fig. 8, the temperature varies at the leakage outlet under different water heads and water temperature differences. Under the condition of temperature > reservoir water temperature, the temperature at the leakage outlet for each water temperature difference shows a gradually decreasing trend with the continuous increase in the water head. The smaller the water head, the closer the temperature of the leakage outlet is to the dam surface temperature. When the water head is 2.5 m, the water–air temperature difference is 10 °C is used to detect leakage. The temperature at the leakage outlet compared to the water–air temperature difference of 5 °C is slightly higher by 0.2 °C. As the water head continues to increase, the temperature value at the leakage outlet tends toward the reservoir water temperature but will not be lower than the reservoir water temperature by 15 °C.

According to the relationship between the temperature at the leakage outlet point and the permeability coefficient of the leakage channel, a quadratic polynomial Eq. (4) was used to fit it, and the fitting curve showed a trend of first rapidly decreasing and then gradually decreasing.

In the formula, \(\text{a}\), \(b\), and \(c\) are constants.

UAV equipped with an infrared thermal imager for leakage inspection of earth–rock dams

From the numerical simulation test of the dam leakage coupled with the seepage and temperature fields, it is known that the water temperature difference affects the degree of temperature field anomaly at the leakage outlet. Therefore, to better detect leakage in earth–rock dams, when conducting on-site inspections of earth–rock dams, priority should be given to selecting time periods with significant temperature differences. On September 13, 2023, a drone equipped with an infrared thermal imager was used for inspection, and a thermometer was used to measure the upstream water temperature of the reservoir at 5.8 °C and 13.6 °C.

Bench berm

The UAV equipped with the infrared thermal imager was used to detect possible leakage in a certain earth–rock dam. As shown in Fig. 9, when air temperature > reservoir water temperature, a low-temperature anomaly appeared in the leakage outlet area of the dam surface. Due to the significant difference between the specific heat capacity of the soil (approximately 0.84 kJ/kg) and the specific heat capacity of the water (approximately 4.2 kJ/kg), under the influence of solar radiation, a thermal difference is typically observed between the reservoir water and the earth–rock dam surface. The normal dam surface is affected by atmospheric radiation and environmental impact, and its temperature will be close to the air temperature, and the heat transfer is uniform. Therefore, when there is a leakage, local thermal anomalies typically occur at the leakage outlet. As shown in Fig. 9b, as the soil around the seepage point continues to absorb water, the surface of the seepage boundary will be soaked by the water, and heat is exchanged with the seepage water flow. The temperature of the soil around the seepage point also increases, forming a temperature zone, which is represented by different colors. As shown in Fig. 9c, the inner boundary of the leakage outlet temperature is 6.5 °C, which is slightly higher than the upstream water temperature due to the influence of thermal convection inside the dam body. The farther the soil is wetted by the seepage water flow at the outer boundary, the more heat is lost by the water flow to the low-temperature air during this process. Therefore, less heat is transferred to the distant soil, causing the temperature value at the outer boundary to be higher than the water temperature but slightly lower than the air temperature, ultimately resulting in a temperature stratification phenomenon characterized by lower values inside and higher values outside.

Dam slope

As shown in Fig. 10a, there is a leakage on the dam slope. When air temperature > reservoir water temperature, and there is leakage on the earth–rock dam surface, the specific heat capacities of the water and earth–rock medium are quite different, leading to an abnormal temperature distribution. Figure 10b shows that the temperature in the water outlet point area of the leakage channel is lower than that in the surrounding normal dam body, and the infrared thermal imaging diagram shows a dark-blue low-temperature area, which is the leakage area found in this detection. The leakage in the dam will also be due to the existence of a slope, resulting in a “trailing” phenomenon of the leakage in the image. In addition, as shown in Fig. 10c, the isotherm of the leakage area exhibits a temperature stratification phenomenon with low values inside and high values outside. The outer boundary temperature of the leakage area was close to the air temperature of 13.6 °C, and the inner boundary temperature was slightly greater than the reservoir water temperature. This is due to the heat conduction between the dam surface and the atmosphere so that the dam surface and the atmosphere maintain a thermal balance, and the dam body is affected by the thermal convection of the reservoir water temperature and the air temperature, and the water temperature at the leakage outlet will slightly increase. Therefore, the temperature field distribution on the earth dam surface can be measured using the infrared thermal imager for the identification and positioning of the leakage area.

Due to the different degrees of leakage in the raceway and dam slope, the temperature anomaly at the leakage outlet varies. Therefore, it is still possible to measure the temperature field distribution on the surface of the earth–rock dam through UAVs equipped with infrared thermal imagers, achieving identification of the leakage area. As a surface sensing technology, IRT does not have internal detection capability. This technique is only effective when the seepage effect approaches or reaches the slope surface. Currently, the main reliance is on manual inspections to detect leakage risks, which may only be effective after the leakage has escaped. In contrast, IRT has the advantages of intuitive visualization, wide coverage, high work efficiency, and can operate normally at night. The rapid identification of leakage hazards in soil and rock embankments during flood season has important application value.

Conclusions

A UAV equipped with an infrared thermal imager was used as a new nondestructive testing technology to detect leakages in earth–rock dams in a natural environment. Based on the coupling theory of the seepage and temperature fields and considering the effects of the water vapor temperature difference and water head, the spatial distribution characteristics of the thermal image of the leakage area were obtained. Better conditions for identifying leakages in earth–rock dams using the infrared thermal imager were explored. The main results and conclusions drawn are as follows:

-

(1)

Based on the flow–heat coupling theory, when there is leakage in an earth–rock dam, the temperature field of the downstream dam surface of the model dam is evidently abnormal, and the temperature field of the dam surface leakage exhibits elliptical spatial distribution characteristics. This proves the feasibility of using the temperature field to identify leakages in the earth–rock dam, and it represents a new technical means to study possible leakages in dams.

-

(2)

Considering the influence of the water head and water–air temperature difference, when the temperature was greater than the water temperature of the reservoir, a low-temperature anomaly appeared at the leakage outlet point on the dam surface. With the increase in the water–air temperature difference and water head, this low-temperature anomaly became increasingly evident, providing a scientific basis for identifying possible leakage in earth–rock dams using the UAV equipped with the infrared imaging technology.

-

(3)

When the UAV-borne infrared imaging method is applied to the actual leakage risk identification in earth–rock dam projects, it is affected by environmental factors related to engineering service. Therefore, the effects of atmospheric transmittance, dam surface emissivity, wind force, and solar irradiation angle were analyzed to ensure the accuracy of the temperature measured by the UAV-borne infrared thermal imager.

-

(4)

In the application of the UAV equipped with the infrared thermal imager to detect leakage on the surface of the earth–rock dam, a low-temperature anomaly appeared in the leakage outlet area, manifesting as a temperature stratification phenomenon with low values inside and high values outside. Due to the existence of the dam slope, a “trailing” phenomenon of leakage was evident in the infrared thermal image.

Our results can serve as a basis for advancing the application of drone technology for the inspection and maintenance of hydraulic infrastructure. Despite these achievements, some shortcomings remain in the existing work. In the process of leakage identification, the human eye must observe the image to achieve leakage identification. Therefore, studying automatic leakage identification algorithms and models is an urgent problem to be solved. Given that the infrared images of dam leakage have distinct contour and brightness features, it is possible to consider transforming the problem of leakage identification into a classification problem of infrared images. In the field of image classification, deep learning has produced advanced results, which can be used for reference. Utilizing pre-trained deep neural networks for transfer learning is a research method worth considering.

Data availability

Some or all data, models, or codes generated or used during the study are available from the corresponding authors by request.

References

Xu, L. et al. Leakage channel outlet detection and diameter estimation for earth-rock dam using ROTDR. Opt. Fiber Technol. 80, 103406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yofte.2023.103406 (2023).

Kiwanuka, M. et al. Dam breach analysis of Kibimba dam in Uganda using HEC-RAS and HEC-GeoRAS. Environ. Syst. Res. 12 (1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40068-023-00317-4 (2023).

Li, P. et al. Research progress on temperature field leakage detection of earth-rock dams and new exploration in leakage point detection. Nondestr. Test. Eval. 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/10589759.2023.2280896 (2023).

Omofunmi, O. et al. A review on effects and control of seepage through earth-fill dam. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 22 (5), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.9734/CJAST/2017/28538 (2017).

Liu, X. & Zhang, X. Study on the characteristics of self-electric field of adjacent multiple leakage paths embankment dams and dikes under variable water levels. Nondestr Test. Eval. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10589759.2024.2327630 (2024).

Zhou, R., Wen, Z. & Su, H. Automatic recognition of Earth rock embankment leakage based on UAV passive infrared thermography and deep learning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. 191, 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2022.07.009 (2022).

Chen, S. S., Zhong, Q. M. & Shen, G. Z. Numerical modeling of earthen dam breach due to piping failure. Water Sci. Eng. 12 (3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wse.2019.08.001 (2019).

Liang, G. Q. et al. Analysis model and method of seepage observation data for Earth rock-fill dams. J. Hydraul. Eng. 02, 83–87. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:0559-9350.2003.02.016 (2003).

Nan, S. et al. Geotechnical, geoelectric and tracing methods for earth/rock-fill dam and embankment leakage investigation. Surv. Geophys. 45 (2), 525–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-023-09806-8 (2024).

Zhou, R., Su, H. & Wen, Z. Experimental study on leakage detection of grassed Earth dam by passive infrared thermography. NDT E Int. 126, 102583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ndteint.2021.102583 (2022).

Gan, J. J., Zhang, Y. X. & Liu, X. An application of the high-density electrical resistivity method for detecting slide zones in deep-seated landslides in limestone areas. J. Appl. Geophys. 177, 104013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jappgeo.2020.104013 (2020).

Danielsen, J. E. et al. The application of the transient electromagnetic method in hydrogeophysical surveys. J. Appl. Geophys. 53 (4), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jappgeo.2003.08.004 (2003).

Feng, R. et al. Electromagnetic tomography: Consistency of images and groundwater prospecting. Acta Seismol. Sin. 10 (5), 649–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11589-997-0028-9 (1997).

Leng, Y. B. et al. The current status and prospects of dam hidden dangers and leakage detection technology in China. Adv. Sci. Technol. Water Resour. 02, 59–62 (2002).

Daniels, D. J. A review of GPR for landmine detection. Sens. Imag. 7 (3), 90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11220-006-0024-5 (2006).

Benedetto, A., Benedetto, F. & Tosti, F. GPR applications for geotechnical stability of transportation infrastructures. Nondestr. Test. Eval. 27 (3), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/10589759.2012.694884 (2012).

Kadioglu, S. & Ulugergerli, E. U. Imaging karstic cavities in transparent 3D volume of the GPR data set in Akkopru dam. Mugla Turk. Nondestr. Test. Eval. 27 (3), 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/10589759.2012.694885 (2012).

Su, H. & Kang, Y. Design of system for monitoring seepage of levee engineering based on distributed optical fiber sensing technology. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/358784 (2013).

Golnabi, H. & Azimi, P. Design and performance of a plastic optical fiber leakage sensor. Opt. Laser Technol. 39 (7), 1346–1350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2006.11.003 (2007).

Bagavathiappan, S. et al. Infrared thermography for condition monitoring-A review. Infrared Phys. Technol. 60, 35–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2013.03.006 (2013).

Hua, L. & Shao, G. The progress of operational forest fire monitoring with infrared remote sensing. J. Res. 28 (2), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-016-0361-8 (2017).

Yu, Y., Zhao, H. L. & Han, L. J. Research on forest fire identification technology based on infrared thermal imaging. Mod. Electron. Tech. 40 (24), 77–79. https://doi.org/10.16652/j.issn.1004-373x.2017.24.025 (2017).

Jadin, M. S. & Taib, S. Recent progress in diagnosing the reliability of electrical equipment by using infrared thermography. Infrared Phys. Technol. 55 (4), 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2012.03.002 (2012).

Kylili, A. et al. Infrared thermography (IRT) applications for Building diagnostics: A review. Appl. Energy. 134, 531–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.08.005 (2014).

Huda, A. S. N. & Taib, S. Application of infrared thermography for predictive/preventive maintenance of thermal defect in electrical equipment. Appl. Therm. Eng. 61 (2), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2013.07.028 (2013).

Bukowska-Belniak, B. & Lesniak, A. Image processing of leaks detection in sequence of infrared images. Pomiary Autom. Kontrola. 63 (4), 131–134 (2017).

Chen, C. Y. et al. Thermal monitoring and analysis of the large-scale field earth-dam breach process. Environ. Monit. Assess. 190 (8), 483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-018-6869-y (2018).

Zhour, R. L. et al. Experimental study on leakage detection of Earth rockfill dams using passive infrared thermography. J. Hydraul. Eng. 53 (1), 14 (2022).

Xu, L. et al. Identification method of dam leakage and layered diseases based on infrared imaging technology. Electron. Technol. Softw. Eng. (08), 134–135. https://doi.org/10.20109/j.cnki.etse.2020.08.057 (2020).

Wang, Y. L., Tang, L. & Qian, S. R. Early unsteady leakage detection system of small reservoir dam based on UAV and infrared thermal image. Nondestr. Test. 42 (12), 61–65. https://doi.org/10.11973/wsjc202012015 (2020).

Peng, B. & Zhang, D. X. Study on detecting concentrated leakage in earth-rock dam by infrared imaging technique. Sci. Technol. Eng. 16 (11), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-1815.2016.11.017 (2016).

Jordan, R., Kinderlehrer, D. & Otto, F. The variational formulation of the Fokker-Planck equation. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 29 (1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1137/S0036141096303359 (1998).

Planck, M. On the law of distribution of energy in the normal spectrum. Ann. Phys. 4 (553), 1 (1901).

Yan, W. Q., Duan, X. B. & Zhou, Z. W. Study on mechanism about influence of seepage field on temperature field. Chin. J. Hydrodyn. 28 (1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn1000-4874.2013.01.006 (2013).

Wang, Y., Zhang, C. & Zhong, J. Three dimensional seepage stability analysis of Earth rock dam crossing structures in plain reservoir. Tech. Superv. Water Resour. 5, 159–163 (2020).

He, Z. P. et al. Influence of distance and fog on infrared temperature measurement accuracy. Infrared Technol. 46 (06), 681–690 (2024).

Guo, P. C. et al. High precision infrared temperature measurement correction algorithm based on multi-channel state perception. Electron. Des. Eng. 31 (08), 105–109. https://doi.org/10.14022/j.issn1674-6236.2023.08.022 (2023).

Zhang, Y. C. et al. The research on the effect of atmospheric transmittance for the measuring accuracy of infrared thermal imager. Infrared Phys. Technol. 77, 375–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2016.06.025 (2016).

Li, Y. H. et al. Theoretical analysis on the technics of temperature measurement precision with infrared thermal imager. J. Xi’an Polytech. Univ. (05), 635–639. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-649X.2007.05.017 (2007).

Mineo, S. & Pappalardo, G. Rock emissivity measurement for infrared thermography engineering geological applications. Appl. Sci. 11 (9), 3773. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11093773 (2021).

Herve, P., Cedelle, J. & Negreanu, I. Infrared technique for simultaneous determination of temperature and emissivity. Infrared Phys. Technol. 55 (1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2010.09.001 (2012).

Sugiura, R., Noguchi, N. & Ishii, K. Correction of low-altitude thermal images applied to estimating soil water status. Biosyst. Eng. 96 (3), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2006.11.006 (2007).

Ma, J. J. et al. Experimental study on leakage detection of Earth dam with infrared thermography. J. Changjiang River Sci. Res. Inst. 40 (03), 131–137 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research has been partially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (SN: 2021YFC3090103), Water Conservancy Technology Demonstration Project (SN: SF-202309), Graduate Thesis Development Fund of Nanjing Hydraulic Research Institute (SN: Yy424006), and Special Fund Project of Basic Scientific Research Business Fee for Central Public Welfare Scientific Research Institutes (SN: Y422009). The authors would like to thank all the reviewers who participated in the review, as well as MJEditor (www.mjeditor.com) for providing English editing services during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.L.: conceived the idea of the article and manuscript writing. L.T.: provided financial support for the work. S.H.Z.: performed experiments and assisted in analyzed the data. P.Z.L. and H.T.: supervised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, P., Tang, L., Zhang, S. et al. Analysis and identification of the temperature field of dam leakage based on infrared thermal imaging. Sci Rep 15, 10551 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95117-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95117-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Comprehensive Evaluation Approach for Earth-Rock Dam Performance Based on Variable Weight Extension Cloud Model

Water Resources Management (2026)