Abstract

Cerebrovascular disease is a common comorbidity in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other dementias. Accumulating evidence suggests that dysfunction of the cerebral vasculature and AD neuropathology interact in multiple ways. Additionally, common variants in COL4A1 and rare variants in HTRA1, NOTCH3, COL4A1, and CST3 have been associated with AD pathogenesis. We aimed to search for rare genetic variants in genes associated with monogenic small vessel disease in a cohort of Portuguese early-onset AD patients. We performed whole-exome sequencing in 104 thoroughly studied patients with early-onset AD who lacked known pathogenic variants in the genes associated with AD or frontotemporal dementia. We searched for rare (minor allele frequency < 0.001) non-synonymous variants in genes associated with small vessel disease: NOTCH3, HTRA1, COL4A1, COL4A2, CSTA, GLA, and TREX1. We identified 12 rare variants in 18 patients (17.3% of the cohort). Three male AD patients carried a pathogenic GLA variant (p.Arg118Cys). One of these patients had a definite neuropathological study, confirming the diagnosis of AD and showing concomitant Fabry pathology in CA1-CA4 and the subiculum. We also found several rare variants in other genes associated with cSVD (NOTCH3, COL4A2 and HTRA1), corroborating previous studies and providing further support for the possibility that cSVD genes may play a role in AD pathogenesis. The presence of the same GLA variant in 3 early-onset AD patients, with no other genetic cause for the disease, together with the colocalization of Fabry disease pathology in areas relevant for AD pathogenesis, suggest GLA may have a role in its pathophysiology, possibly parallel to that of GBA in Parkinson’s disease, meriting further studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cerebrovascular pathology is highly prevalent in different degrees across general population1, acting as a comorbidity in other types of dementia2,3. It is still debated whether cerebrovascular lesions add incrementally to the cognitive burden, or if vascular dysfunction acts synergistically with other neurodegenerative disorders4. Besides the shared risk factors5 that may concur for the development of more than one disorder, some evidence supporting a role for blood-brain barrier dysfunction6 and other vascular changes preceding Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) changes also exists7.

For example, neuropathological studies have shown that cerebrovascular pathology is a major risk factor for clinically diagnosed AD8. In fact, 80% of patients diagnosed with AD have some degree of cerebrovascular pathology9, even if they do not meet the criteria for mixed (i.e. vascular) dementia. Vascular dysfunction also appears early in AD10 and is associated with several hallmarks of AD, such as amyloid-beta deposition11 and tau pathology12.

This overlap of cerebrovascular and traditional AD pathologies is not exclusive to the late-onset form of AD but is also present in autosomal dominant AD13. Recently, NOTCH3 (Neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 3, the gene associated with the most common cause of inherited vascular dementia - CADASIL) has been associated with AD14,15, indicating that genes associated with cerebral Small Vessel Disease (cSVD) may also play a role in neurodegenerative dementias. Other studies have also implicated COL4A1 (Collagen, type IV, Alpha 1) and HTRA1 (High Temperature Requirement serine protease A1) in AD pathogenesis16, further supporting this view. Proteins coded by these genes can impact on other pathways that may be involved in AD pathogenesis, such as NOTCH3, that is cleaved by the presenilins that cleave APP17, HTRA1 on APOE (Apolipoprotein E) metabolism18, or GLA (Galactosidase Alpha) on autophagy, lysosomal function, lipid metabolism and inflammation19.

In this study, we aimed to find rare variants in genes associated with monogenic small-vessel disease in a cohort of Portuguese early-onset AD patients.

Methods

Subjects

In this study, we included 104 index early-onset AD patients recruited from a memory clinic in Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra, Portugal, a tertiary reference hospital from the central region of Portugal. The diagnosis was performed according to the most widely accepted criteria for AD20 and supported by extensive characterization. Our clinical protocol includes (1) a complete and systematic clinical and neuropsychological evaluation; (2) a structural neuroimaging (computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)); (3) lumbar puncture to determine AD cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers, and/or amyloid PET (Positron Emission Tomography) in selected cases. Since we are studying genes leading to cSVD, patients who displayed signs of significant vascular burden (large cortico-subcortical infarct, extensive subcortical white matter lesions superior to 25%, uni- or bilateral thalamic lacunes, lacunes in the head of the caudate nucleus and more than 2 lacunes)21 demonstrated by brain computed tomography or MRI were not considered in this study.

Ethics

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Coimbra University Hospital and biological samples were obtained following written informed consent from the patients’ legal representatives. Research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Exome sequencing

Exome sequencing was performed on all patients using a HiSeq2500 with 75–100 bp pair-end reads after library preparation with the SureSelect Exome Capture Kit v4 (Agilent). Exome data processing was done following GenomeAnalysisTK best practices. Alignment was done to the hg19 genome assembly using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (bwa-mem) v0.7.12. Duplicates were identified with samblaster v0.1.21 and bases were recalibrated with GenomeAnalysisTK v3.8-122. Variant Quality Score Recalibration23, and annotation with snpEff v4.2 and dbNSFP v2.9 were applied to all variants24,25. Variants were filtered according to their quality metrics as described by Patel and collaborators26. Identical by descent (IBD) statistics were inferred with KING27 and only unrelated patients were included.

Variant analysis

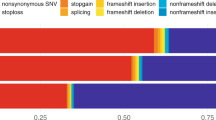

We explored variants in the nuclear genes associated with inherited cSVD28: NOTCH3 (associated with CADASIL), HTRA1 (associated with CARASIL), CTSA (Cathepsin A, associated with CARASAL), TREX1 (Truncated three prime Exonuclease-1, associated with Retinal Vasculopathy with Cerebral Leukodystrophy and Systemic manifestations), COL4A1 (associated with Pontine Autosomal Dominant Microangiopathy and Leukoencephalopathy), COL4A2 (encoding Alpha 2 chain of type IV Collagen) and GLA (encoding α-galactosidase A, associated with Fabry disease). All patients were previously screened for pathogenic mutations in APP (Amyloid Precursor Protein), PSEN1 (Presenilin 1), PSEN2 (Presenilin 2), GRN (Progranulin) and MAPT (Microtubule Associated Protein Tau), and C9ORF72 (chromosome 9 open reading frame 72) expansions, which were not found. Exome data was also surveyed for definite pathogenic changes in the other genes associated with frontotemporal dementia and other forms of dementia (listed in29), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (as reported in30).

Only rare variants were included in the study. Variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.001 in GnomAD v2.1.1 overall sample, or in any of the detailed subpopulations were excluded, except when the variants have been reported to be pathogenic before. In silico pathogenicity prediction was assessed using SIFT (Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant)31, Polyphen-232, PROVEAN (Protein Variation Effect Analyzer)33, Mutation Taster202134 and CADD (Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion)35. Cutt-offs were as defined by each tool. For CADD PHRED scores we did not classify as pathogenic or not, as there is not an established cut-off, the 10% most pathogenic variants have CADD of 10, the 1% most pathogenic variants have CADD 20 and so on. The relevant findings were comprehensively assessed by considering MAF (Minor allele frequency), predicted pathogenicity, disease association, and family history. Literature and available databases were also surveyed to check for previous reports on the found variants.

Neuropathological analysis

One patient donated his brain for research to the Portuguese Brain Bank of Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Santo António. It was fixed in a 4% aqueous solution of formaldehyde for three weeks prior to diagnostic cutting and selection of brain regions of interest for paraffin-embedded tissue blocks.

Histological studies with haematoxylin and eosin, Klüver- Barrera, and immunohistochemistry [\(\:{\upalpha\:}\)-synuclein, ubiquitin, SQSTM1/p62, phosphorylated tau (AT8), TDP-43, GFAP, amyloid-β, CD77] were performed in 6 μm paraffin-embedded formalin-fixed sections from selected brain regions. Appropriate consent procedures for the collection and use of human brain tissue by the PBB were approved by the National Ethics Committee.

Results

Sixty-four out of 104 (61.5%) early-onset AD patients were female. The average age of onset was 54.8 ± 5.5 years. We found 12 rare variants in 18 patients (17.3% of the cohort), as described in Table 1.

In NOTCH3, we found 6 rare variants in 9 patients (p.Met2280Val, p.Arg2234His, p.Arg1895Leu, p.Val1141Met, p.Leu691Ile, p.Glu74Lys). Of these, p.Arg1895Leu and p.Val1141Met, both present in two patients each, were predicted to be damaging by in silico tools. Further, two additional patients carried the p.Met2280Val variant.

We further identified 6 rare variants in 9 patients (1 patient carried 2 variants; and two variants were present in more than one patient) in GLA, COL4A2 and HTRA1, accounting for 8.7% of the cohort (Table 1). We did not find rare variants in COL4A1, CTSA or TREX1.

GLA variants

We identified a previously reported pathogenic GLA variant (p.Arg118Cys) in 3 male AD patients (Table 2). Two had CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) collected, with CSF biomarkers suggestive of AD. None of the patients had an ischemic lesion burden considered to be the cause of the dementia. None had other reported Fabry symptoms, but this was not systematically assessed, since Fabry disease was not suspected in any of the patients. Alpha-galactosidase levels were not assessed for any of the patients, as they had died prior to the present study. One had AD since the age of 61 and died of subarachnoid hemorrhage at the age of 71. Other had AD since the age of 62 years and the third one since the age of 64, none with clinical vascular events. All were APOE ε3ε3.

One of the patients (patient A) underwent postmortem neuropathological examination, which revealed a 1034 g brain with global atrophy, particularly involving the occipital-parietal and hippocampal regions (Fig. 1A). The locus coeruleus was severely depigmented. Histological examination revealed severe AD neuropathology (NIA – AD neuropathological change high likelihood: A3, B3, C3; NFT (Neurofibrillary tangle) stage V36; Aβ-amyloid phase 537; CERAD (Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease): frequent neuritic plaques) (Fig. 1B and C). Additionally, there was Aβ CAA (Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy) (Vonsattel grade 2)38, moderate atherosclerotic disease, small vessel change without vascular lesions, and Lewy body pathology (α-synuclein) in the medulla at the level of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve and medullary reticular formation compatible with stage 1 Parkinson’s Disease (PD)39.

After WES results, we performed immunohistochemistry with a monoclonal mouse antibody anti-CD77 (1:200; Clone 5B5; BioLegend, San Diego, CA) for recognition of Fabry disease-associated Gb3 deposits. We found CD77 immunoreactivity in hippocampal sectors CA1-CA4 and, to a lesser extent, in the subiculum (Fig. 1D and E).

Discussion

Here, we aimed to assess the possible role of genes associated with monogenic small vessel disease and AD. We identified three AD patients carrying a known pathogenic GLA variant (p.Arg118Cys), which causes Fabry disease, a monogenic cSVD. One of these patients had neuropathological data showing both AD and Fabry pathology, linking the two diseases for the first time. Fabry pathology was identified in regions typically associated with AD, further supporting the linking of both phenotypes.

We also found several rare variants in other genes associated with cSVD (NOTCH3, COL4A2 and HTRA1) in AD patients, corroborating previous studies and providing further support for the possibility that cSVD genes may play a role in AD pathogenesis.

GLA

GLA, located at the Xq22.1, encodes α-galactosidase A, a lysosomal enzyme classically associated with Fabry disease (FD). α-Galactosidase A main function is to catalyze the removal of terminal α-galactose groups from substrates such as glycoproteins and glycolipids. In FD, its deficiency leads to accumulation of neutral glycosphingolipids. The mechanism of tissue damage is considered to be at least partly due to poor perfusion caused by accumulation in the vascular endothelium, particularly in the kidneys, heart, nervous system, and skin. However, defects in autophagy, lysosomal function, lipid metabolism, and inflammation have also been implicated28. FD can present as a severe, classical phenotype, most often seen in males without residual enzyme activity, and a generally milder nonclassical phenotype40. This phenotype, also referred to as late-onset or atypical FD, is characterized by a more variable disease course, in which patients are generally less severely affected and disease manifestations may be limited to a single organ40.

During the past decade, GLA has been increasingly associated with PD41,42,43, suggesting a role for it in neurodegeneration. In fact, reduced alpha-galactosidase A levels have been reported in PD patients and correlate with α-synuclein deposition, hinting at an association of GLA changes with autophagy-lysosome pathway dysfunction44, which has also been shown to be involved in the pathophysiology of AD. Interestingly, it has been shown that, in the brain, the accumulation of globotriaosylceramid is not restricted to vessels, but also occurs in the substantia nigra, neocortex, hippocampal formation, brainstem, amygdala, hypothalamus, and entorhinal cortex45,46, possibly suggesting that these areas may be more susceptible to alpha-galactosidase A dysfunction. In fact, Fabry disease has been linked with hippocampal atrophy and global atrophy47. Noteworthy, although sexual chromosomes have been largely understudied in AD48, X-chromosome appears to carry some of the risk for AD49.

All 3 of our patients carrying a rare variant in GLA had the same variant (Arg118Cys). Although this variant’s pathogenicity has been disputed50,51,52, it has been shown to lead to a mild/moderate deficiency of α-Galactosidase A activity50 and to some changes characteristic of the disorder50,52, with a later age of onset50,52. It is now postulated that this and other variants may be associated with milder forms with later onset of dysfunction53. Our neuropathological data supports this variant’s pathogenicity. Moreover, the localization of FD pathology in CA1, an area associated with early AD pathology neurodegeneration process36 raises the possibility of the association of this variant with AD and should prompt further studies to determine the frequency of AD-related pathology in FD patients. The presence of α-synuclein-positive lesions restricted to the medulla oblongata and corresponding to PD stage 1 indicates that FD patients also can display Lewy pathology and, thus, ultimately may be capable of developing parkinsonism46. Unfortunately, we were unable to assess the presence of Lewy body pathology at the level of the spinal cord and peripheral autonomic or enteric nervous systems. None had a positive first-degree family history.

We can draw a parallel with GBA, also a lysosomal enzyme. GBA homozygous pathogenic variants lead to Gaucher disease, whereas heterozygous carriers have an increased risk of PD54. Different mechanisms have been postulated for the association of GBA with PD, different from the one that causes Gaucher Disease. The most probable are (1) retainment of the misfolded protein in the endoplasmic reticulum, activating the unfolded protein pathway; (2) the lysosomal dysfunction and subsequent impairment of the autophagic-lysosomal pathway; (3) accumulation of aberrant lipid forms that affect the membrane composition; (4) neuroinflammation; and (5) accumulation of defective mithocondria55. In the case of GLA, we hypothesize that some (more disruptive) variants lead to the accumulation of neutral glycosphingolipids and FD. Some other less disruptive variants, which do not cause early-onset Fabry disease, can cause cellular dysfunction that increases the accumulation of misfolded proteins and, ultimately, AD (as well as PD). The same pattern of different phenotypes at different ages caused by different degrees of pathogenicity in the same gene is seen in other autosomal genes, such as GRN and TREM2.

NOTCH3

Mutations in the EGFr domain on the external surface of the NOTCH3 protein lead to misfolding and gradual accumulation in the vascular smooth muscle56. This mechanism fits the Cerebral Autosomal Recessive Arteriopathy with Subcortical infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) pathobiology, but does not fit well with the known AD mechanisms. NOTCH receptors undergo proteolytic processing via γ-secretase in a manner comparable to that of APP. This suggests that interactions between these signaling pathways may be related with AD mechanisms57. We found six rare NOTCH3 variants in nine patients (8.7% of the cohort). None of these variants involved cysteine residues in the EGFr domain of the protein, which are typically associated with CADASIL58.

The p.Arg1895Leu variant leads to a change in a residue in a highly conserved ANK domain59. Interestingly, this region is vital for GSK3β binding59. GSK3β is considered to be central in AD pathology, namely in tau phosphorylation60. The impact of NOTCH3 phosphorylation by GSK3β is yet to be determined, but this relationship may be relevant for AD pathogenesis. The Met2280Val has been found in one AD patient and none of the 95 controls in a previous study61. We found this variant in two of our patients. It changes a residue just before the PEST domain. Mutations in the PEST domain have been associated with activation of NOTCH signalling62, which has been implicated in adult hippocampal neurogenesis63. Interestingly, one of the other variants (p.Arg2234His) we found is located in the same region. A similar trend is seen in other similar studies64 adding interest to our findings.

Although cysteine-changing variants were absent from our cohort, we demonstrate that rare variants in NOTCH3 may be frequent in EOAD patients. Of the ones we report, those with the higher probability of association with disease lie outside the EGFr region, typically associated with CADASIL, and are located in regions associated with the intracellular NOTCH signaling.

COL4A2 and HTRA1

COL4A1 and COL4A2 encode the α1 and α2 chains of type IV collagen, a major component of the basement membrane65. Mutations in COL4A1 and COL4A2 are associated with a variety of diseases, including cSVD. COL4A2 is known to harbor less variants reported as pathogenic65, most of them changing a Glycine residue. We found 4 rare variants in our cohort (reported in Table 1). Most of these variants are predicted to be pathogenic by in silico tools, but further studies would be needed to assess their possible role in disease.

HTRA1 encodes a serine protease that is involved in a variety of cellular processes, including apoptosis, angiogenesis, and inflammation. Mutations in HTRA1 cause Cerebral Autosomal Recessive Arteriopathy with Subcortical infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy (CARASIL), a rare autosomal recessive cSVD. Heterozygous HTRA1 mutations have also been shown to cause autosomal dominant small vessel disease66, sometimes leading to dementia. HTRA1 is an allele-selective ApoE-degrading enzyme, that degrades ApoE ε4 faster than APOE ε3, having a potential role in the mechanisms underlying AD. We found one AD patient carrying the p.Val433Ile variant in HTRA1. This variant has not been previously reported in the literature67.

The findings of our study suggest that COL4A2 and HTRA1 variants may play a role in AD pathogenesis. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings and to elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Overall, our study provides new insights into the genetic overlap between cSVD and AD. Our findings suggest that cSVD associated genes may be a more important risk factor for AD than previously thought, and that targeting cSVD pathways may be a relevant therapeutic approach for AD. However, our study has some limitations. First, our sample size was relatively small. Second, we did not perform functional validation of the genetic variants that we identified, particularly of the association of the reported variants with the corresponding phenotype. These are thoroughly studied patients, most of them with very early onset dementias without a genetic cause identified by exome sequencing, increasing the potential for an association of these genes with the observed AD phenotype. Still, we can neither confirm pathogenicity nor establish a definite link between the changes and the phenotype. Third, we do not have pathological confirmation of the diagnosis of AD in the majority of patients. Yet, we combine CSF and/or PET biomarkers and a long follow-up from an experienced team. Moreover, the main finding of our study was corroborated by neuropathological data.

Conclusion

We found several rare variants on the genes of interest in our cohort. We show that three unrelated carriers of the GLA p.Arg118Cys variant, without other probable genetic cause responsible for the disease, have developed early-onset AD. One of these cases had post-mortem confirmation of the diagnosis and we further show the colocalization of Fabry pathology in areas relevant for AD pathogenesis, suggesting a role for GLA in AD. The association of GLA with AD suggested in this study relies on two main points. First, the finding of Fabry pathology in a patient’s brain carrying the GLA p.Arg118Cys variant supports the potential pathogenic role of this variant in the disease. Second, the fact that we identified this same GLA rare variant in 3 out of 104 early-onset AD patients (2.9% vs. 0.0008% of Non-Finnish European in gnomAD) where exome sequencing did not show any other probable genetic cause for the disease, and considering the rarity of the variants and the phenotype, indicates that this overlap is not likely to be an incidental finding.

In the future, functional data and animal models can give further support to this association. Fabry disease has some forms of treatment, and can indicate an additional genetic therapeutic target for EOAD patients. If confirmed, this association would also add stronger evidence to the role of lysosomal involvement in AD pathogenesis.

Data availability

Data is available by contacting the corresponding author (Miguel Tábuas-Pereira).

References

Petrovitch, H. et al. AD lesions and infarcts in demented and non-demented Japanese-American men. Ann. Neurol. 57, 98–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.20318 (2005).

Raz, L., Knoefel, J. & Bhaskar, K. The neuropathology and cerebrovascular mechanisms of dementia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 36, 172–186. https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2015.164 (2016).

De Reuck, J. et al. Aging and cerebrovascular lesions in pure and in mixed neurodegenerative and vascular dementia brains: a neuropathological study. Folia Neuropathol. 56, 81–87. https://doi.org/10.5114/fn.2018.76610 (2018).

Solis, E., Hascup, K. N. & Hascup, E. R. Alzheimer’s disease: the link between Amyloid-β and neurovascular dysfunction. J. Alzheimers Dis. 76, 1179–1198. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200473 (2020).

Serrano-Pozo, A. & Growdon, J. H. Is Alzheimer’s disease risk modifiable?? J. Alzheimers Dis. 67, 795–819. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD181028 (2019).

Yamazaki, Y. & Kanekiyo, T. Blood-Brain barrier dysfunction and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. IJMS 18, 1965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18091965 (2017).

The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative et al. Early role of vascular dysregulation on late-onset Alzheimer’s disease based on multifactorial data-driven analysis. Nat. Commun. 7, 11934. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11934 (2016).

Arvanitakis, Z., Capuano, A. W., Leurgans, S. E., Bennett, D. A. & Schneider, J. A. Relation of cerebral vessel disease to Alzheimer’s disease dementia and cognitive function in elderly people: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 15, 934–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30029-1 (2016).

Toledo, J. B. et al. Contribution of cerebrovascular disease in autopsy confirmed neurodegenerative disease cases in the National Alzheimer’s coordinating centre. Brain 136, 2697–2706. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awt188 (2013).

Sweeney, M. D. et al. Vascular dysfunction – the disregarded partner of Alzheimer’s disease, Alzheimers Dement 15 158–167. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.07.222

Gottesman, R. F. et al. Mosley, association between midlife vascular risk factors and estimated brain amyloid deposition. JAMA 317, 1443–1450. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.3090 (2017).

Vemuri, P. et al. Age, vascular health, and alzheimer disease biomarkers in an elderly sample. Ann. Neurol. 82, 706–718. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25071 (2017).

Lee, S. et al. Dominantly inherited alzheimer network, white matter hyperintensities are a core feature of alzheimer’s disease: evidence from the dominantly inherited alzheimer network. Ann. Neurol. 79, 929–939. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24647 (2016).

Sassi, C. et al. Mendelian adult-onset leukodystrophy genes in Alzheimer’s disease: critical influence of CSF1R and NOTCH3. Neurobiol. Aging. 66, 179e17–179179. .e29 (2018).

Patel, D. et al. Association of rare coding mutations with alzheimer disease and other dementias among adults of European ancestry. JAMA Netw. Open. 2, e191350. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1350 (2019).

Pang, C. et al. Identification and analysis of Alzheimer’s candidate genes by an amplitude deviation algorithm. J. Alzheimers Dis. Parkinsonism. 9, 460. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0460.1000460 (2019).

De Strooper, B. et al. A presenilin-1-dependent gamma-secretase-like protease mediates release of Notch intracellular domain. Nature 398, 518–522. https://doi.org/10.1038/19083 (1999).

Chu, Q. et al. HtrA1 proteolysis of ApoE in vitro is allele selective. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 9473–9478. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.6b03463 (2016).

Li, X. et al. Fabry disease: mechanism and therapeutics strategies. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 1025740. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1025740 (2022).

McKhann, G. M. et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 7, 263–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005 (2011).

van Straaten, E. C. W. et al. Operational definitions for the NINDS-AIREN criteria for vascular dementia. Stroke 34, 1907–1912. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000083050.44441.10 (2003).

McKenna, A. et al. The genome analysis toolkit: A mapreduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.107524.110 (2010).

Auwera, G. A. et al. From FastQ data to High‐Confidence variant calls: the genome analysis toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr. Protocols Bioinf. 43 https://doi.org/10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43 (2013).

Cingolani, P. et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of drosophila melanogaster strain W 1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 6, 80–92. https://doi.org/10.4161/fly.19695 (2012).

Liu, X., Jian, X. & Boerwinkle, E. DbNSFP v2.0: A database of human Non-synonymous SNVs and their functional predictions and annotations. Hum. Mutat. 34, E2393–E2402. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.22376 (2013).

Patel, Z. H. et al. hbGerard The struggle to find reliable results in exome sequencing data: filtering out Mendelian errors, Front. Genet. 5 (2014). https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2014.00016

Manichaikul, A. et al. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 26, 2867–2873. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq559 (2010).

Mancuso, M. et al. Monogenic cerebral small-vessel diseases: diagnosis and therapy. Consensus recommendations of the European academy of neurology. Eur. J. Neurol. 27, 909–927. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14183 (2020).

Guerreiro, R. et al. Genetic architecture of common non-Alzheimer’s disease dementias. Neurobiol. Dis. 142, 104946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2020.104946 (2020).

Tábuas-Pereira, M. et al. Exome sequencing of a Portuguese cohort of frontotemporal dementia patients: looking into the ALS-FTD continuum. Front. Neurol. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.886379 (2022).

Ng, P. C. & Henikoff, S. Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genome Res. 11, 863–874. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.176601 (2001).

I. Adzhubei, D.M. Jordan, S.R. Sunyaev, Predicting Functional Effect of Human Missense Mutations Using PolyPhen-2, Current Protocols in Human Genetics / Editorial Board,Jonathan L. Haines … et Al.] 0 7 (2013) Unit7.20. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76.

Choi, Y., Sims, G. E., Murphy, S., Miller, J. R. & Chan, A. P. Predicting the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. PLoS One. 7, e46688. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0046688 (2012).

Steinhaus, R. et al. MutationTaster Nucleic Acids Research 49 (2021) W446–W451. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab266

Schubach, M., Maass, T., Nazaretyan, L., Röner, S. & Kircher, M. CADD v1.7: using protein Language models, regulatory CNNs and other nucleotide-level scores to improve genome-wide variant predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D1143–D1154. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad989 (2024).

Braak, H. et al. Staging of alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 112, 389–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z (2006).

Thal, D. R., Rüb, U., Orantes, M. & Braak, H. Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 58, 1791–1800. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.58.12.1791 (2002).

Vonsattel, J. P. et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy without and with cerebral hemorrhages: a comparative histological study. Ann. Neurol. 30, 637–649. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410300503 (1991).

Braak, H. et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 24, 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9 (2003).

Arends, M. et al. Characterization of classical and nonclassical Fabry disease: A multicenter study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28, 1631–1641. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2016090964 (2017).

Lackova, A. et al. Prevalence of Fabry disease among patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2022, 1014950. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/1014950 (2022).

Gago, M. F. et al. Parkinson’s disease and Fabry disease: clinical, biochemical and neuroimaging analysis of three pedigrees. J. Parkinsons Dis. 10 (n D) 141–152. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-191704

Müller, S. et al. Del Tredici, Morbus Fabry and Parkinson’s Disease-More evidence for a possible genetic link. Mov. Disord. 39, 449–451. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.29686 (2024).

Nelson, M. P. et al. The lysosomal enzyme alpha-Galactosidase A is deficient in Parkinson’s disease brain in association with the pathologic accumulation of alpha-synuclein. Neurobiol. Dis. 110, 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2017.11.006 (2018).

Okeda, R. & Nisihara, M. An autopsy case of Fabry disease with neuropathological investigation of the pathogenesis of associated dementia. Neuropathology 28, 532–540. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1789.2008.00883.x (2008).

Del Tredici, K. et al. Fabry disease with concomitant lewy body disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 79, 378–392. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnen/nlz139 (2020).

Cocozza, S., Russo, C., Pontillo, G., Pisani, A. & Brunetti, A. Neuroimaging in Fabry disease: current knowledge and future directions. Insights Imaging. 9, 1077–1088. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13244-018-0664-8 (2018).

Moreno-Grau, S. et al. GR@ACE study group, DEGESCO consortium,,,,,,, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, Long runs of homozygosity are associated with Alzheimer’s disease, Transl Psychiatry 11 142. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-01145-1

Tábuas-Pereira, M. et al. Exploring first-degree family history in a cohort of Portuguese Alzheimer’s disease patients: population evidence for X-chromosome linked and recessive inheritance of risk factors. J. Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-024-12673-x (2024).

Ferreira, S. et al. The alpha-galactosidase A p.Arg118Cys variant does not cause a Fabry disease phenotype: data from individual patients and family studies. Mol. Genet. Metab. 114, 248–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.11.004 (2015).

Baptista, M. V. et al. PORTuguese young STROKE investigators, mutations of the GLA gene in young patients with stroke: the PORTYSTROKE study–screening genetic conditions in Portuguese young stroke patients. Stroke 41, 431–436. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.570499 (2010).

Cerón-Rodríguez, M., Ramón-García, G., Barajas-Colón, E., Franco-Álvarez, I. & Salgado-Loza, J. L. Renal globotriaosylceramide deposits for Fabry disease linked to uncertain pathogenicity gene variant c.352C > T/p.Arg118Cys: A family study. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 7, e981. https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.981 (2019).

Vieitez, I. et al. Fabry disease in the Spanish population: observational study with detection of 77 patients. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 13, 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-018-0792-8 (2018).

Sidransky, E. et al. Multicenter analysis of glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl. J. Med. 361, 1651–1661. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0901281 (2009).

Smith, L. & Schapira, A. H. V. Variants and Parkinson disease: mechanisms and treatments. Cells 11, 1261. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11081261 (2022).

Tikka, S. et al. Congruence between NOTCH3 mutations and GOM in 131 CADASIL patients. Brain 132, 933–939. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awn364 (2009).

Hartmann, D., Tournoy, J., Saftig, P., Annaert, W. & De Strooper, B. Implication of APP secretases in Notch signaling. J. Mol. Neurosci. 17, 171–181. https://doi.org/10.1385/JMN:17:2:171 (2001).

Xu, X. et al. Insights into autoregulation of Notch3 from structural and functional studies of its negative regulatory region. Structure 23, 1227–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2015.05.001 (2015).

C, B. P. L. J. O., K, P. & U, L. The origin of the Ankyrin repeat region in Notch intracellular domains is critical for regulation of HES promoter activity. Mech. Dev. 104 https://doi.org/10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00373-2 (2001).

Llorens-Martín, M., Jurado, J., Hernández, F. & Avila, J. GSK-3β, a pivotal kinase in alzheimer disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 7, 46. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2014.00046 (2014).

Guerreiro, R. J. et al. Exome sequencing reveals an unexpected genetic cause of disease: NOTCH3 mutation in a Turkish family with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 33, 1008e17–1008e23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.10.009 (2012).

Wang, K. et al. PEST domain mutations in Notch receptors comprise an oncogenic driver segment in triple-negative breast cancer sensitive to a γ-secretase inhibitor. Clin. Cancer Res. 21, 1487–1496. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1348 (2015).

Ehret, F. et al. Mouse model of CADASIL reveals novel insights into Notch3 function in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Neurobiol. Dis. 75, 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2014.12.018 (2015).

Guo, L. et al. The role of NOTCH3 variants in Alzheimer’s disease and subcortical vascular dementia in the Chinese population. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 27, 930–940. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.13647 (2021).

Meuwissen, M. E. C. et al. The expanding phenotype of COL4A1 and COL4A2 mutations: clinical data on 13 newly identified families and a review of the literature. Genet. Med. 17, 843–853. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2014.210 (2015).

Verdura, E. et al. Heterozygous HTRA1 mutations are associated with autosomal dominant cerebral small vessel disease. Brain 138, 2347–2358. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv155 (2015).

Uemura, M. et al. HTRA1-Related cerebral small vessel disease: A review of the literature. Front. Neurol. 11, 545. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00545 (2020).

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG067426. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author roles 1) conception and design of the study, 2) acquisition and analysis of data or 3) drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures. Miguel Tábuas-Pereira: 1,2,3. José Brás: 1, 2, 3. Ricardo Taipa: 2. Kelly del Tredici: 2. Kimberly Paquette: 2. Sophia Chaudhry: 2. Kaitlyn Westra: 2. João Durães: 2. Marisa Lima: 2. Catarina Bernardes : 2. Inês Baldeiras: 2. Maria Rosário Almeida: 2. Isabel Santana: 1,2,3. Rita Guerreiro: 1,2,3.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tábuas-Pereira, M., Brás, J., Taipa, R. et al. Exome sequencing of a Portuguese cohort of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease implicates the X-linked lysosomal gene GLA. Sci Rep 15, 11653 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95183-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95183-8