Abstract

Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii) spawn in large aggregations, releasing gametes individually. It is unclear the mechanism of group spawning such as behavioral synchrony and persistence on fine scale due to the difficulty of direct observation. The present study used acceleration data loggers to examine the behavioral changes on a fine scale during a spawning event. We conducted the experiment using 911 fish in a large tank. Data loggers were attached to 15 males and 38 females. After the first individual changed behavior, the acceleration change occurred synchronously in many individuals within 30–40 min. This acceleration changes seemed to reflect the sequence of spawning behavior such as rising, milling, substrate testing, and releasing gametes. Additionally, these behavioral changes then occurred in cycles of 105–210 min. It seemed that pheromone stimulation triggered this behavioral synchrony, while habituation to pheromones caused the cycles of behavioral changes. We suggest that behavior synchrony on fine scale is essential for increasing fertilization rate. Additionally, timing the release of gametes may avoid the risks of wasting gametes by releasing them in adverse conditions. These mechanisms are essential for herring to increase their reproductive success.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reproductive behavior is fundamental to most species offspring success1,2,3. In species with sexual reproduction, mating behavior depends on the environment in which the species lives4. In general, mating behavior is directly related to reproductive success5 and sexual selection6; therefore, it is essential to understand these behaviors in each environment in the field of evolutionary ecology.

The mating behavior of fish is especially varied because of diverse offspring protection styles and the ability of some species to change sex7,8. Group spawning is a common system used by many species in which individuals form aggregations to spawn and both sexes repeatedly release sperm and eggs individually9. There are various forms of group spawning, such as in the blue sprat (Spratelloides gracilis), where many individuals individually repeat spawning10 and in the giant bumphead parrotfish (Bolbometopon muricatum), which repeatedly spawn in small groups of around 10 individuals11. In any form of spawning event, spawning by multiple individuals synchronously is considered advantageous for increasing the mate encounter rates and fertilization success9. The synchronization of the group spawning event is affected by the lunar cycle, tide cycle, water temperature, and salinity9,12,13,14. These spawning synchronizations occur several times during the spawning season15. The synchronized spawning behavior increases the fertilization rate and minimizes the risks of predation and environmental change as much as possible by dispersing the eggs and sperm within the spawning period. However, many previous studies of group spawning events have focused on the scale of days and months, while few studies have focused on a fine scale of hours and minutes because of the difficulty in tracking the behavior of individuals. Even on a fine scale, mechanisms may exist for behavioral synchronization and risk aversion. These mechanisms should be evaluated on a fine scale to obtain a greater understanding of individual reproductive success.

Among species that spawn in groups, Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii) form particularly large spawning aggregations of several hundred thousand to over a million fish and are essential for fishery resources in Hokkaido, Japan. Owing to the large number of individuals participating in spawning, complex mechanisms may underly the synchronization and dispersal of spawning behavior. Additionally, because the herring is a primitive teleost fish species, the species is used as an essential model in ecology and evolutionary research16. Therefore, herring are suitable for examining the mechanisms of behavioral synchronization and risk aversion on a fine scale. Herring migrate to coastal areas in large groups during the spawning season from winter to spring, and spawn on seaweed beds every year17,18. During their spawning event, they spawn individually rather than forming pairs. Stacey and Hourston (1982) observed and classified the behaviors of herring during a spawning event as rising and milling, papilla extension, substrate testing by placing their abdomen against the substrate, and releasing sperm and eggs by rubbing their body on the substrate19. It is thought that pheromones from released sperm induce other individuals to release gametes20,21. Therefore, studies suggest that males release sperm, followed by females releasing eggs, leading to large-scale group spawning20,21,22. However, because it is difficult to recognize the sex of fish based on their appearance and the water becomes cloudy due to sperm as the spawning event proceeds, the actual transition of the sexes during group spawning is unclear23. Although herring release gametes individually during group spawning, the release of gametes may be synchronized on an hour and minute scale to increase the fertilization rate. Additionally, it is unclear how long individual spawning behavior persists. Herring spawn in a large space and time scale24,25, but it is unclear whether an individual spawns for a long time. Previous studies of Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) have shown that a high density of eggs causes high mortality because of low oxygen supply26,27. In addition, because fertilized eggs are sensitive to environmental changes23,28, the eggs may be wasted if all gametes are released at once during adverse environmental conditions. Therefore, it is possible that individuals do not release gametes over a long period (hours) to avoid these risks.

The spatiotemporal analysis of behavior requires the continuous measurement of the behavior of several individuals. The biologging method in which a logger is attached to the animal body enables researchers to visualize the behavior in situations in which behavior is difficult to observe, such as underwater and in the dark29. This method has been used to visualize foraging behavior and migration, and has been introduced to measure spawning behavior in fish30,31,32. In particular, acceleration data loggers are suitable for recording behavioral changes during spawning33,34. Therefore, in the present study, acceleration data loggers were attached to several individual herrings, and a group spawning event was induced in an experimental tank. Because the data loggers record acceleration and depth over time, we were able to visualize the changes in behaviors during the spawning event: rising and milling, substrate testing, and releasing sperm and eggs. We evaluated these behavioral changes in individuals and examined the synchronicity and persistence of the behavioral changes during a spawning event on a fine scale.

Methods

Laboratory experiment

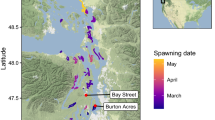

We collected 911 sexually mature Pacific herring using a coastal set net (43.650786, N, 145.170506, E) in Shibetsu in eastern Hokkaido on 20 April 2023 during the new moon (Fig. 1). The fish were carried by a live fish transporting truck (10 m long, 2.5 m wide) to the Hakodate Research Center for Fisheries and Oceans (Hokkaido, Japan) within 10 h (Fig. 1). The truck was equipped with four tanks (each with a 3 tonne volume) in which the water was kept clean by filter circulation and the water temperature was maintained at 4℃ (the same temperature as the seawater at the time of sampling). The fish were promptly transported to a large experimental tank (10 m wide × 5 m long × 3.4 m deep; Fig. 2) at the facility.

The experiment was conducted from 21 to 22 April 2023. From rearing to the experiment, the lights were kept on during the day and turned off at night. The fish were not provided with food from the time of capture until the conclusion of the experiment. Because the spawning event tend to occur in calm water18,35, there were no water flow in the tank. And we also didn’t use filtration circulation to avoid the noise from machine interfering with the induction of spawning. Two cameras (WTW-320 H, Wireless Tsukamoto Co., Ltd., Mie, Japan) were placed in the tank to observe a spawning event. In addition, two network cameras (Tapo C200, TP-Link Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) were placed in the front and side of the tank for the preliminary observation of the environment of the tank. A net was used to prevent the fish from contacting the filters in the tank (Fig. 2). Four 1-m-long artificial seaweed units (Mozya Mozya, Okabe Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were placed locally in the tank to provide spawning substrate for the herring and to encourage chain reactions of spawning behavior (Fig. 2A–D). We created the artificial seaweed by wrapping sheets of seaweed around cylinders (Fig. 3). After the experiment, we estimated the number of eggs attached to the seaweed. To estimate the number of eggs, we measured the total weight of 10 randomly selected eggs 10 times. We then averaged these values and divided the average value by 10 to calculate the approximate weight of one egg. Finally, the difference in the weight of the seaweed before versus after the experiment was divided by the weight of one egg to obtain the total number of eggs attached to the seaweed. To confirm the distribution of eggs, each of the four artificial seaweed units were numbered 1–4, and the number of eggs on each seaweed was counted (Fig. 3). Measurements of eggs and the seaweed were carried out under identical conditions after the water was thoroughly drained.

The plastic sheets were wrapped around cylinders (1 m long, 14 cm diameter) to make the artificial seaweed. Each artificial seaweed was wrapped by four plastic sheets. The seaweed units were numbered from 1 to 4, starting from the top of the cylinder to enable the estimation of the number of eggs deposited in each region of the seaweed.

Tagging

Of the 911 herring, 15 males (mean fork length 28.44 ± 1.47 cm; mean mass 275.50 ± 55.00 g) and 38 females (mean fork length 28.86 ± 2.03 cm; mean mass 317.06 ± 80.18 g) had acceleration data loggers (axy5Depth, TechnoSmArt Co., Ltd., Rome, Italy; 3.5 g in air) attached. Because of the sensitivity of the herring to handling, we used an external attachment method without using chemical anesthesia36,37. Each fish was measured to determine the body mass. Then, the upper side of the fish body in front of the dorsal fin was pierced using needles (3 mm diameter) and the logger was attached using a cable tie (3 mm wide). To prevent inflammation, two cushions were placed between the logger and the fish body. The entire process from measuring the body mass to tagging was conducted within less than 2 min. The fish with the attached loggers were promptly released into the experimental tank. The experiment began after 2-hour recovery period to avoid any impact of the tagging and release on the subsequent behavior. While a recovery period of approximately half a day to one day is generally recommended38, the risk of the spawning event beginning in the tank made it necessary to shorten the acclimation period to 2 h in this study. During the 2-hour recovery period, the fish were observed to swim normally and it was assumed that tagging did not have a significant impact on their swimming behavior. All researchers who participated in this study had completed an ethics course on animal experiments at Hokkaido University. All experiments were conducted following the ethical regulations for animal experiments of Hokkaido University.

Data analysis

Tri-axial acceleration was recorded at 1/25 second intervals with maximum values of ± 4 G, and the depth and temperature were recorded at 1 Hz. X-axis acceleration was recorded in the head-tail direction, Y-axis acceleration was recorded in the dorsoventral direction, and Z-axis acceleration was recorded in the lateral direction (Fig. 2). Gravity-delivered static acceleration reflected the postural changes, and motion-delivered dynamic acceleration was recorded in each axis39 (Fig. 2). Fish that propel themselves by fin movement, such as herring, often produce continuous and cyclic signals. In the present experiment, we measured cyclic signals with a high frequency component in 0.5 s; these values were separated as dynamic acceleration, while the other accelerations were measured as static acceleration using a running mean of 0.5 s40. Pitch acceleration was static acceleration of the X-axis, while roll acceleration was static acceleration of the Z-axis. Pitch acceleration reflected the up-down postural changes, while roll acceleration reflected the rotation of the fish body (Fig. 2). To convert the pitch acceleration (G) and roll acceleration (G) to an angle (°), we used the following equations.

Surge acceleration reflected the acceleration and deceleration in the direction of swimming, whereas sway acceleration reflected the movement of the fins. From the sway acceleration, we calculated the tailbeat as the number of swings of the tail fin per second. In addition, we calculated the overall dynamic body acceleration (ODBA), which is often used as an indicator of activity41, as the sum of the dynamic acceleration from all three axes. Acceleration, depth, and temperature data were downloaded, visually observed, and analyzed using IGOR Pro ver. 6.37 (WaveMetrics Inc., Lake Oswego, OR, USA) and Ethographer software42.

When herring spawn, they mill around the substrate, test the substrate, and release sperm and eggs by moving their tail fins19. In addition, herring spawn on a large spatial scale in the wild and it has been suggested that they spawn widely so that they are not biased in one place24,25. Considering these spawning characteristics, we analyzed the following seven parameters: (1) pitch, (2) roll, (3) surge, (4) tailbeat, (5) ODBA, (6) average depth, (7) depth range. (1)–(3) To evaluate variations in postural changes and acceleration or deceleration changes in the direction of movement over time, we calculated the standard deviation (SD) every 5 min of the pitch, roll, and surge (hereafter referred to as pitch_SD, roll_SD, and surge_SD, respectively). (4) To evaluate changes in tail fin movement, we averaged the tailbeat every 5 min. (5) To evaluate changes in the activity level, we averaged the ODBA every 5 min. (6) To evaluate changes in depth, we averaged the depth every 5 min. (7) The depth range was calculated as the difference between the minimum and maximum depth every 5 min.

A generalized additive model (GAM) with smoothing splines was used to examine how the behavior of both sexes changed over time. Each of the seven parameters was used as a response variable, the elapsed time during the experiment was used as the explanatory variable, and the identity of the individual fish was used as the random factor. We used two-way ANOVA to examine the effects of time and sex on the predicted line from the GAM. In addition, to examine the cycle of spawning behavior, we examined the autocorrelation with the predicted lines of each parameter. By examining the differences between the lags where peaks were observed, we determined the cycles of the predicted lines from the GAM. For statistical analyses, we used R. ver.4.0.2 software with the GAM function in R packages mgcv and the acf function.

We also examined the percentage of individuals who changed their behavior during the time series. We determined a parameter of interest from the logger data, and judged whether individuals displayed the behavioral change every 10 s. The threshold values used to judge behavioral changes were based on comparisons of data between swimming and spawning. On the basis of the video camera observations, 10 min immediately after the start of the experiment (19:00–19:10) was used as the normal swimming period, while 2 h after the start of the experiment (21:00–21:10) was used as the spawning period.

After the experiment, we dissected 53 logger-tagged herring and 97 non-tagged herring and recorded the fork length, body weight, gonad weight, maturity stage, and sex. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the gonadosomatic index (GSI: the percentage of the total fish weight accounted for by the gonads) between males and females to determine the remaining unreleased gametes after the spawning event.

Results

Logger-equipped fish swam normally during this experiment from the observation. A total of 10 h of logger data were obtained from 19:00 on 21 April 2023 to 5:00 on 22 April 2023, including the spawning event. The video showed that several herring rubbed their abdomens against seaweed 1 h and 20 min after the start of the experiment (20:20; Supplementary Fig. 1). However, on the basis of the video observation, it was unclear whether this behavior was seaweed testing or gamete release. Then, 2–3 min later, several fish obviously released sperm and eggs. Many individuals then released sperm and eggs 30–40 min later (Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Movie 1). We could not make observations 2 h after start of the experiment (21:00) because the sperm made the water in the tank too cloudy. Thus, it was unclear whether the same individuals continued releasing gametes for a long period.

We used the GAM to examine the relationships between elapsed time during the experiment and seven parameters: (1) pitch_SD, (2) roll_SD, (3) surge_SD, (4) tailbeat, (5) ODBA, (6) average depth, (7) depth range. We used these parameters as explanatory variable, time as response variable, and individual number as random factor. For all parameters, the predicted line from the GAM did not increase or decrease monotonically but varied irregularly over time (Fig. 4). Two-way ANOVA showed that time had significant effects on each parameter, and sex had significant effects on some parameters (Table 1; Fig. 4(1)–(7)). The pitch_SD showed the most marked change of the seven parameters. 2 h after start of the experiment (21:00), which seemed to be the peak of the group spawning event, the vertical posture changed greatly (Fig. 4(1)). The change in the tailbeat showed a similar trend to the pitch_SD. 5 h after start of the experiment (1:00), the tailbeat tended to increase in both sexes (Fig. 4(4)). In addition, after the initiation of the spawning event, the average depth tended to be shallow and the depth range became wide. After 0:00, the fish swam deeply, but not as deep as before spawning (Fig. 4(6)). The depth range became narrow 4 h after start of the experiment (0:00), but still tended to be wider than before the spawning event (Fig. 4(7)).

Results of the generalized additive model with smoothing splines. We examined the following seven parameters: (1) pitch_SD, (2) roll_SD, (3) surge_SD, (4) tailbeat, (5) ODBA, (6) average depth, (7) depth range. Each parameter was used as a response variable, time was used as the explanatory variable, and individual identification numbers were used as random factors. Red and blue lines show the predicted values of females and males. Gray areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. The y-axis of the graph is inverted for (6) average depth only.

We examined the cycle of behavior using correlograms. A significant autocorrelation was found from the correlograms of all parameters. The correlograms of the roll_SD and depth range had one peak, the correlograms of the pitch_SD, surge_SD, tailbeat, ODBA, and average depth had two peaks, and the correlogram of the tailbeat had three peaks (Fig. 5; Table 2). We also calculated the differences between the lags where peaks were observed. The difference between the lags ranged from 21 to 42. One point of lag represented 5 min; therefore, the parameters had a cycle in the range of 105–210 min.

We analyzed the ratio of spawning individuals as the group spawning event proceeded. The data from three males and three females that were thought to have spawned based on the differences in their body weights before versus after the experiment showed that the pitch_SD was more than twice as large during spawning than during swimming (Supplementary Fig. 2). Therefore, we defined the threshold of the behavioral change as twice the value of the pitch_SD during normal swimming. The result supported the observation, as the figure showed that the number of spawning individuals increased (Fig. 6). Each mark on the x-axis represents 10 s. One hour and 20 min after the start of the experiment (20:20), approximately 13% of both males and females changed their behavior (Fig. 6). This shows that the change in behavior did not differ between sexes at the start of the spawning event. The increase in the ratio started in the same manner as that on the video when we visually confirmed the first behavioral changes at about 20:20. After 2 h (21:00), which seemed to be the peak of the spawning event, 40% of males and 42% of females changed their behavior. We did not evaluate the difference in the timing of the peak of the spawning event and the trends of increased behavior between sexes.

Red and blue bars show the ratio of spawning individuals. We defined a spawning individual as an individual with a pitch_SD that was more than twice as large as that recorded during normal swimming. The ratio was calculated by dividing the counted results by the number of individuals with loggers and multiplying by 100. Each mark on the x-axis represents 10 s.

We found eggs on all four artificial seaweed units (Supplementary Fig. 3a), with an estimated one million eggs in total on seaweed. In addition, many eggs were found on the separate net, suggesting that more eggs were actually laid (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Many eggs were laid on the seaweed and the net at a depth of 1–2 m (Supplementary Fig. 3b), while few eggs were laid at position 4 on the seaweed and on the lower part of the net at a depth of about 3 m (Table 3).

The dissection of 97 non-tagged fish revealed that 45 were males and 52 were females. Among the 53 fish with loggers attached, 15 were males and 38 were females. We created a histogram using 60 males and 90 females. The GSI showed bimodal peaks at 0 and 20% in both sexes (Fig. 7). The female GSI was significantly greater than the male GSI (p < 0.01; Mann-Whitney U test; Fig. 7).

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the mechanisms of group spawning such as the synchrony and persistence of behavioral changes. We conducted the experiment in a large tank using 911 fish with data loggers on 15 males and 38 females. The spawning event occurred in the experiment at nearly new moon at night, consistent with findings reported in a previous study14. Additionally, because herring are more likely to spawn in calm environments18,35, we didn’t use filtration circulation to eliminate water flow and noise, established a quiet environment that closely resembled natural conditions. On the other hand, it should be noted that the tank was completely enclosed as a result. In addition, it also should be noted that short time of acclimation period post-capture and transport (about 24 h) in this experiment. Likewise, this experiment began after 2 h recovery period from tagging whereas previous study have required 24 h37. A 2-hour acclimation period is generally insufficient for cortisol levels to decrease, indicating that the fish had not fully acclimated from tagging38. However, due to the high densities and the calm environment in the tank, which increased the risk of an early spawning event43, we were compelled to shorten the acclimation period to 2 h. Despite this limitation, from our observation, there was no difference in swimming behavior between the tagged and untagged herring, and, as observed in previous studies, we were able to confirm the sequence of spawning behavior such as rising and milling, substrate testing, and releasing gametes19. Additionally, we did not conduct chemical anesthesia, which is considered to have a significant impact. Therefore, while full recovery might not have been achieved within this time frame, we propose the short time of acclimation did not significantly affect the interpretation of our results.

Characteristics of logger data during the spawning event

The change in the roll_SD was smaller than that in the pitch_SD. This result may reflect the characteristics of the artificial seaweed. Although most eggs were deposited on the artificial seaweed, eggs were also deposited on the tank walls and the separate net. Because the cylinders wrapped with sheets of seaweed were elongated vertically, the fish may have moved vertically and rubbed their abdomens on the seaweed. Pacific herring usually lay eggs on seaweed around coastal areas, but rarely spawn on rocks23. The changes in the pitch or roll may depend on the substrate on which the herring lay their eggs or release sperm. In addition, the fish were swimming in a narrow area before spawning, and swam in a wide area after spawning (Fig. 4). Studies have suggested that many fish, including herring, use visual sensations to form a group37,44,45. In the present experiment, it was thought that the herring swam widely after spawning because their ability to form a group decreased due to the tank becoming cloudy after the release of sperm.

Synchronization and cyclicity during the group spawning event

Many fish species perform synchronized spawning events46,47,48. In the case of Pacific herring, although it varies between locations, the group spawning frequently occurs in the neap tide following a new moon and at night14,24. As egg mortality is affected by many factors49, a few spatiotemporal differences may be related to egg mortality. Therefore, individuals may release gametes over time to disperse the risks of wasting gametes by releasing them in adverse environmental conditions. Previous studies have evaluated these phenomena only on a large time scale14,50, while the present study is the first to track individuals and evaluate their behavioral changes during a spawning event on a fine time scale.

Our experiment showed that the behavior of both sexes changed synchronicity. One hour and 20 min after the start of the experiment (20:20), the behavior of many individuals changed within a short period of only 30–40 min; therefore, the sequence of the rising and milling behavior, seaweed testing behavior, and spawning behavior seemed to occur in a short period (Figs. 4 and 6). We think that the pheromones from released sperm were diluted and spread throughout the tank, which caused other individuals to respond by rubbing on and testing seaweed and releasing sperm and eggs. Although it was unclear whether individuals actually released gametes, it seemed that they were sensitive to pheromones released from other fish, even though the pheromones were diluted. Thus, it is thought that individuals detected the release of sperm and eggs by other individuals and then performed rising and milling behavior or seaweed testing behavior and were ready to release gametes. The spawning event then peaked 2 h and 10 min after the start of the experiment (21:10), and the behavioral changes became small after 3 h and 30 min (22:30) (Fig. 4). In addition, the correlograms showed that the behavior changed in cycles of 105–210 min (Fig. 5). A previous study suggested that exposure to high pheromone concentrations in a short period is more essential for inducing the release of gametes than exposure to diluted pheromones for a long period20. Additionally, it has been suggested that even individuals exposed to high concentrations of pheromones become gradually accustomed to the pheromones, making it difficult to induce gamete release from about 2 h after the first pheromone stimulation20. Considering these previous findings, we suggest that the behavioral change in the cycle of 105–210 min was associated with the fish becoming accustomed to the pheromones in the present experiment (Fig. 5). We think that the control of behavior by pheromone habituation might lead to the dispersal of the risks of gamete destruction. Previous studies have shown that the egg survival rate is affected by environmental factors such as salinity and temperature, which are influenced by slight spatiotemporal differences, as well as by predation from other fish and birds23,28,49. Additionally, many studies have shown that a high egg density of Atlantic herring causes an increased mortality rate because of a lack of oxygen to the eggs on the inside of the clutch26,27. Therefore, distributing the release of gametes over time avoids the risks of wasting gametes, which is essential for the individual to increase their reproductive success. The mechanism of suppression of spawning behavior at a specific time by habituation to pheromones, which we found in the present study, has merit in that an individual does not release all their gametes at once and can thus release gametes in different environments. As a result, the individual can spatiotemporally distribute the release of gametes, even on a fine scale, which disperses the risks of wasting gametes. In conclusion, we suggest that in the spawning event of Pacific herring, the synchronization occurs because of the stimulation of pheromones, which might be related to increasing the fertilization rate, while the behavior is also controlled due to habituation to the pheromones, which might be related to the avoidance of the risks of gamete destruction.

Scale of the group spawning event

In the present study, we observed the spawning behavior of many individuals until the tank water became too cloudy with sperm and found that the group spawning of herring could be reproduced in the experimental tank. The dissection showed that some individuals had a low GSI, which suggests that some individuals released all of their gametes in this spawning event (Fig. 7). In contrast, several individuals had a high GSI, which suggests that there were also some individuals that released only a few gametes (Fig. 7). There was enough space for the herring to lay their eggs after the experiment (Table 3). Additionally, the sex ratio in the present experiment was approximately 1:1 and the fish matured just before spawning. Thus, although all the necessary factors for a spawning environment seemed to be present, not all individuals released all of their gametes. This may be because the artificial seaweed spawning grounds were concentrated in one area, which meant that only individuals that swam near the seaweed were exposed to high concentrations of pheromones and induced to spawn. Therefore, the pheromones may induce other individuals to spawn when seaweed is widely distributed, as occurs in a large-scale spawning event17,24,50.

It seems that environmental differences in factors such as the aggregation size and seaweed distribution determine whether each individual releases all of their gametes. If the individual is in a suitable environment, it can release all of its gametes and produce offspring; however, if the spawning environment is not suitable, the release of gametes may be stopped until the next spawning event or to be used as energy source. Skip-spawning has been observed in Atlantic herring, suggesting that gametes are reabsorbed and used as energy for the following year51,52. Thus, we think that when and how many gametes an individual releases are essential to increase the reproductive success of individuals, and that the release of gametes is affected by pheromone-induced behavior and the suppression of such behaviors due to habituation to pheromones.

Behaviors of males and females during the spawning event

Pheromones from released sperm induce the spawning behavior of other individuals, and therefore some studies have suggested that pheromones trigger the spawning event19,20,21,22. However, in our study, there was no difference in the change of behavior between sexes (Fig. 6). When a few males release sperm, individuals of both sexes near the males that released the sperm are induced to release gametes. Therefore, the difference between sexes in the release of gametes may only appear in the first few individuals that spawn at the beginning of the event. This may explain why there were no differences between sexes in our experiment in which many individuals were used. However, to increase the fertilization rate, it is essential that there are no differences in behavioral changes between sexes (Figs. 4 and 6). Herring sperm can survive for 2 days, as the sperm are normally less motile and become more active in the presence of eggs53,54,55. Additionally, herring eggs are able to be fertilized for 5 h56. Previous studies have suggested that the sperm and eggs must exist in a fine spatiotemporal scale for fertilization, which supports our result that the behavior of both sexes changed synchronously on a fine scale during the spawning event (Figs. 4 and 6). However, it should be noted that the present experiment only revealed changes in the behavior of both sexes, and it was not possible to determine the actual time scale of synchrony of the behaviors of releasing sperm and eggs. In further study, using the biologging method to characterize the acceleration data (such as the tailbeat frequency during sperm and egg release) will enable the frequency and timing of sperm and egg release to be determined in detail, which will reveal the reproductive biology of the sexes.

We found that the females had a significantly larger GSI than the males (Fig. 7). This may be because female gametes are heavier than male gametes24,57,58, even without considering the effects of the present experiment. However, the distribution of the male GSI was also more widely varied than that of the female GSI; therefore, it is possible that the males released small amounts of sperm at a high frequency. Further study is needed to determine whether the amount of gametes released differs between the sexes during one spawning event. The amount of released gametes may be related to the difference between sexes in the number of spawning events in which herring participate during their lifetime, and the differences between sexes in the pattern of migration to spawn.

Future perspectives about group spawning

In the present study, we examined the behavioral cycles using the biologging method and found that the behavior of Pacific herring was synchronous, even on a fine scale. However, observing fish behavior during this experiment was particularly challenging because the water became cloudy due to sperm and the mixing of many individuals. Additionally, it was difficult to identify individual fish tags under these conditions. For these reasons, it was not possible to focus on the detailed behavior of individual fish. In the future, conducting small-scale experiments to identify acceleration changes associated with behaviors such as seaweed testing and gamete release could help reveal the mechanisms of group spawning in detail. This may also provide insights into the timing of spawning events in the wild.

During the group spawning event of these fish, it has been assumed that they mate with as many individuals as possible. However, as shown in the present study, it is possible that individuals do not fully release all of their gametes in a single spawning event to avoid the risks of gamete destruction as a result of predation or adverse environmental conditions. Among fish with extensive mating opportunities, the timing of sperm and egg release may be determined by many factors; further research is needed to reveal these factors, which may be elucidated using the biologging method to record individual behavior.

Data availability

The datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Barrett, S. C. H. & Harder, L. D. Ecology and evolution of plant mating. Trends Ecol. Evol. 11, 73–79 (1996).

Bonduriansky, R. The evolution of male mate choice in insects: a synthesis of ideas and evidence. Biol. Rev. 76, 305–339 (2001).

Clutton-Brock, T. H. Review Lecture: Mammalian Mating Systems. The Royal Society Proceedings B 236, 339–372 (2024).

Emlen, S. T. & Oring, L. W. Ecology, sexual selection, and the evolution of mating systems. Science 197, 215–223 (1977).

Anholt, R. R. H., O’Grady, P., Wolfner, M. F. & Harbison, S. T. Evolution of Reproductive Behavior. Genetics 214, 49–73 (2020).

Andersson, M. & Iwasa, Y. Sexual selection. Trends Ecol. Evol. 11, 53–58 (1996).

Sefc, K. M. Mating and Parental Care in Lake Tanganyika’s Cichlids. Int J Evol Biol 2011, 470875 (2011).

Kuwamura, T., Sunobe, T., Sakai, Y., Kadota, T. & Sawada, K. Hermaphroditism in fishes: an annotated list of species, phylogeny, and mating system. Ichthyol. Res. 67, 341–360 (2020).

de Yvonne, S. M., Patrick L., C. Reef Fish Spawning Aggregations: Biology, Research and Management, Chap. 3. (Springer, New York, USA, 2012).

Takeuchi, N. & Gushima, K. Promiscuous spawning behaviour of the tropical herring spratelloides gracilis. J. Fish Biol. 68, 310–317 (2006).

Roff, G., Doropoulos, C., Mereb, G. & Mumby, P. J. Mass spawning aggregation of the giant Bumphead Parrotfish Bolbometopon muricatum. J. Fish Biol. 91, 354–361 (2017).

Takemura, A., Rahman, M. S., Nakamura, S., Park, Y. J. & Takano, K. Lunar cycles and reproductive activity in reef fishes with particular attention to rabbitfishes. Fish Fish. 5, 317–328 (2004).

Colin, P. L. Reproduction of the Nassau Grouper, epinephelus striatus (Pisces: Serranidae) and its relationship to environmental conditions. Environ. Biol. Fish. 34, 357–377 (1992).

Hay, D. E. Tidal influence on spawning time of Pacific herring (Clupea harengus pallasi). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 47, 2390–2401 (1990).

Donahue, M. J., Karnauskas, M., Toews, C. & Paris, C. B. Location isn’t everything: timing of spawning aggregations optimizes larval replenishment. PLOS ONE 10, e0130694 (2015).

Geffen, A. J. Advances in herring biology: from simple to complex, coping with plasticity and adaptability. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 66, 1688–1695 (2009).

Haegele, C. W., Humphreys, R. D. & Hourston, A. S. Distribution of eggs by depth and vegetation type in Pacific herring (Clupea harengus pallasi) spawnings in Southern British Columbia. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 38, 381–386 (1981).

Hoshikawa, H. et al. Characteristics of a Pacific herring Clupea Pallasii spawning bed off Minedomari, Hokkaido, Japan. Fisheries Sci. 70, 772–779 (2004).

Stacey, N. E. & Hourston, A. S. Spawning and feeding behavior of captive Pacific herring, Clupea harengus pallasi. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 39, 489–498 (1982).

Carolsfeld, J., Tester, M., Kreiberg, H. & Sherwood, N. M. Pheromone-Induced spawning of Pacific herring. I. Behavioral characterization. Horm. Behav. 31, 256–268 (1997).

Carolsfeld, J., Scott, A. P. & Sherwood, N. M. Pheromone-Induced spawning of Pacific herring. II. Plasma steroids distinctive to fish responsive to spawning pheromone. Horm. Behav. 31, 269–279 (1997).

Yanagimachi, R. Studies of fertilization in Clupea pallasii. II. Structure and activity of spermatozoa. Zoological Soc. Japan 66, 222–225 (1957). (in Japanese with English summary).

Haegele, C. W. & Schweigert, J. F. Distribution and characteristics of herring spawning grounds and description of spawning behavior. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 42, 39–55 (1985).

Hay, D. E. Reproductive biology of Pacific herring (Clupea harengus pallasi). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 42, s111–s126 (1985).

Hay, D. E., McCarter, P. B., Daniel, K. S. & Schweigert, J. F. Spatial diversity of Pacific herring (Clupea pallasi) spawning areas. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 66, 1662–1666 (2009).

Kanstinger, P. et al. What is left? Macrophyte meadows and Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) spawning sites in the Greifswalder Bodden, Baltic sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 201, 72–81 (2018).

von Nordheim, L., Kotterba, P., Moll, D. & Polte, P. Impact of spawning substrate complexity on egg survival of Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus, L.) in the Baltic sea. Estuaries Coasts. 41, 549–559 (2018).

Jones, B. C. Effect of intertidal exposure on survival and embryonic development of Pacific herring spawn. J. Fish. Res. Bd Can. 29, 1119–1124 (1972).

Chung, H., Lee, J. & Lee, W. Y. A. Review: Marine Bio–logging of Animal Behaviour and Ocean Environments. Ocean Science Journal 56, 117–131 (2021).

Manco, F., Lang, S. D. J. & Trathan, P. N. Predicting foraging dive outcomes in chinstrap Penguins using biologging and animal-borne cameras. Behav. Ecol. 33, 989–998 (2022).

McKinnon, E. A. & Love, O. P. Ten years tracking the migrations of small landbirds: lessons learned in the golden age of bio-logging. Auk 135, 834–856 (2018).

Tsuda, Y. et al. Vertical movement of spawning cultured Chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus) in a net-cage. Aquaculture 422–423, 136–140 (2014).

Whitney, N., Pratt, H., Pratt, T. & Carrier, J. Identifying shark mating behaviour using three-dimensional acceleration loggers. Endang Species Res. 10, 71–82 (2010).

Seki, K., Ichimura, M., Ihara, N. & Makiguchi, Y. Changes in courtship prior to oviposition in Chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) and male preference for female body size. Ecol. Freshw. Fish. 33 (2), 1–11 (2023).

Lee, Y. D., Choi, J. H., Moon, S. Y., Lee, S. K. & Gwak, W. S. Spawning characteristics of Clupea Pallasii in the coastal waters off Gyeongnam, Korea, during spawning season. Ocean. Sci. J. 52, 581–586 (2017).

Tomiyasu, M. et al. Sonic tagging reveals age and size-specific Spatial variation during Pacific herring spawning migrations in Northern Japan. Fish. Res. 242, 106020 (2021).

Tomiyasu, M. et al. Can Swimming Depth Data from Multiple Pacific Herring Individuals Be Used to Estimate Characteristics of Their School? Verification by Micro Bio-loggers. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 27, (2019).

Lower, N. et al. A non-invasive method to assess the impact of electronic Tag insertion on stress levels in fishes. J. Fish Biol. 67, 1202–1212 (2005).

Yoda, K. et al. A new technique for monitoring the behaviour of free-ranging Adélie Penguins. J. Exp. Biol. 204, 685–690 (2001).

Shepard, E. et al. Derivation of body motion via appropriate smoothing of acceleration data. Aquat. Biol. 4, 235–241 (2008).

Gleiss, A. C., Wilson, R. P. & Shepard, E. L. C. Making overall dynamic body acceleration work: on the theory of acceleration as a proxy for energy expenditure. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2, 23–33 (2011).

Sakamoto, K. Q. et al. Can ethograms be automatically generated using body acceleration data from Free-Ranging birds?? PLoS ONE 4, e5379 (2009).

Tomiyasu, M. et al. Utilization of artificial seaweed and fishing net as spawning bed of Pacific herring Clupea Pallasii in natural habitats. Fisheries Eng. 55 (3), 193–197 (2019).

Partridge, B. L. & Pitcher, T. J. The sensory basis of fish schools: relative roles of lateral line and vision. J. Comp. Physiol. 135, 315–325 (1980).

Larsson, M. Why do fish school. Curr. Zool. 58, 116–128 (2012).

Ohta, I. & Ebisawa, A. Inter-annual variation of the spawning aggregations of the white-streaked grouper epinephelus Ongus, in relation to the lunar cycle and water temperature fluctuation. Fish. Oceanogr. 26, 350–363 (2017).

Motohashi, E., Yoshihara, T., Doi, H. & Ando, H. Aggregating behavior of the grass puffer, Takifugu niphobles, observed in aquarium during the spawning period. Zoolog. Sci. 27, 559–564 (2010).

Hoque, M. M., Takemura, A., Matsuyama, M., Matsuura, S. & Takano, K. Lunar spawning in Siganus canaliculatus. J. Fish Biol. 55, 1213–1222 (1999).

Rooper, C. N., Haldorson, L. J. & Quinn, I. I. Habitat factors controlling Pacific herring (Clupea pallasi) egg loss in Prince William sound, Alaska. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 56, 1133–1142 (1999).

Hay, D. E. & Kronlund, A. R. Factors affecting the distribution, abundance, and measurement of Pacific herring (Clupea harengus pallasi) spawn. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 44, 1181–1194 (1987).

Engelhard, G. H. & Heino, M. Dynamics in frequency of skipped reproduction in Norwegian spring-spawning herring. 2004 ICES Annual Science Conference, Vigo, Spain. (2004).

Kennedy, J. et al. Evaluation of the frequency of skipped spawning in Norwegian spring-spawning herring. J. Sea Res. 65, 327–332 (2011).

Griffin, F. J. et al. Effects of salinity on sperm motility, fertilization, and development in the Pacific herring, Clupea pallasi. Biol. Bull. 194, 25–35 (1998).

Yanagimachi, R., Cherr, G. N., Pillai, M. C. & Baldwin, J. D. Factors controlling sperm entry into the micropyles of salmonid and herring eggs. Dev. Growth Differ. 34, 447–461 (1992).

Cherr, G. N. et al. Two egg-derived molecules in sperm motility initiation and fertilization in the Pacific herring (Clupea pallasi). Int. J. Dev. Biol. 52, 743–752 (2008).

Yanagimachi, R. Studies of fertilization in Clupea pallasii. I. Extension of the fertilizable life of the unfertilized eggs by means of isotonic Ringer’s solution. Zoological Soc. Japan. 66, 218–221 (1957).

Rajasilta, M., Paranko, J. & Laine, P. T. Reproductive characteristics of the male herring in the Northern Baltic sea. J. Fish Biol. 51, 978–988 (1997).

Ware, D. M. & Tanasichuk, R. W. Biological basis of maturation and spawning waves in Pacific herring (Clupea harengus pallasi). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 46, 1776–1784 (1989).

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. T. Onose and the members of Shibetsu Fisheries Cooperative Association and the staff of the Shibetsu Salmon Museum for their help with fieldwork. We also thank Mr. T. Iwamori and the laboratory members who contributed to this experiment. This work was supported by JST SPRING, Grant Number JPMJSP2119. Finally, we thank Kelly Zammit, BVSc, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K. S., M. T., M. K., and K. M. designed the experiment. K. S. and M. I. performed the field work. K. S., Z. Y., and K. M. conducted the experiment. K. S., M. T., and N. S. analyzed the data. K. S. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seki, K., Tomiyasu, M., Kuroda, M. et al. Temporal changes in behavior during the group spawning event of Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii). Sci Rep 15, 11337 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95189-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95189-2