Abstract

Network modeling are widely using in resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) research. Typically, Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) was widely applied to construct brain connectivity network from BOLD signals of regions of interest. However, it often results in significant intra-group variability and complicates the identification of disease-specific functional connectivity patterns. To address this issue, we propose a novel brain network construction strategy, called SNBG, which uses aggregated information from the control group to derive a single-sample network. We compare SNBG and the PCC based method on a dataset from an Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) study. SNBG method captures more stable connections between regions of interest (ROIs) and increases classification accuracy from 89.24% of PCC based method to 97.13%. In addition, in AD-related local networks, such as default mode network (DMN), medial frontal network (MFN) and frontoparietal network (FPN), SNBG demonstrates lower intra-group heterogeneity than the PCC based method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, brain network analysis based on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has become a widely used method in neuroscience research1,2. This approach helps researchers understand the fundamental principles of brain function and structure by examining the connections and topological structures between regions of interest (ROIs). It facilitates the exploration of information transfer, functional modularity, and other characteristics, revealing the role of brain networks in cognitive and behavioral processes. Studying the evolution and development of brain networks can illuminate changes during development and learning, as well as provide insights into the pathological mechanisms of brain diseases, offering new perspectives and methods for diagnosis and treatment.

As age increases, both the structural and functional network topologies of the brain undergo changes3. In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a neurodegenerative disorder, these networks exhibit characteristics such as impaired connectivity4,5, altered topology6, abnormal functional partitioning7, and reduced dynamics8. From the perspective of disease progression, differences in network structures have been observed in subregions related to information exchange and memory, such as gray matter, white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, hippocampus, and corpus callosum9,10, as patients progress from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to diagnosed AD. Changes in functional connectivity are seen not only in visual, auditory, and somatosensory areas but also in olfactory regions11. In two highly associated ROIs, the default mode network (DMN) and the executive control network, there is a combined effect of cerebrovascular disease and brain network degeneration12. Thus, changes in brain diseases can be effectively represented through network modeling, and brain network analysis provides a topological explanation for distinguishing AD13,14,15.

Many researchers integrate network topology with computer science to determine AD using network features. Whether using global and local topological properties of the entire brain network as features for training classification models or judging based on the topological features of key ROIs. Constructing brain functional connectivity networks based on the Pearson correlation coefficient is a common research method. Cao et al. explored the relationship between attention deficits after pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) and the topological properties and dynamic changes of brain functional networks by constructing brain networks using the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC), and identified abnormal networks related to the disease16. Chen et al. conducted an effective disease classification study on the data of MCI patients using the brain network constructed based on PCC17. In addition, many other studies have realized the analysis of connectivity between ROIs through the PCC, providing effective evidence for the research of brain functional networks18,19. However, the impact of differences between individual networks within the same group cannot be overlooked in complex real-world brain connections. Thus, in this work, we further explore constructing more representative functional networks and propose a group-based single-sample network construction method, named SNBG.

This study utilizes resting-state fMRI data to construct brain networks using both the PCC based method and our SNBG method. SNBG builds upon the PCC, using healthy control group data as a foundation. By applying linear interpolation, the matrix data of the target sample is horizontally concatenated with the overall sample matrix data of the healthy group. The connectivity between pairs of ROIs is then calculated, and the difference from the group correlation matrix of healthy samples yields the correlation matrix for the target sample. By statistically analyzing the frequency of connections between pairs of ROIs in the network, we demonstrate that the SNBG method can construct more stable ROI connections, making it easier to capture potential connections related to AD. For intra-group analysis, we calculated node degree and global efficiency on the constructed networks as indicators for comparing local and global network features. Results show that the SNBG method effectively reduces intra-group variability. In inter-group classification experiments, we used common features like node degree and network clustering coefficient for training and classification testing in an Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier. The results indicate that the SNBG method achieves higher classification accuracy, demonstrating its effectiveness.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and preprocessing

The Resting-state functional magnetic resonance image (rs-fMRI) data were sourced from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI). In order to avoid the influence of irrelevant factors in the original data on the method validation, we selected the rs-fMRI images with a time point of 140 collected by Philips instruments. The clinical data were not included in the database. To ensure the uniformity of the preprocessing methods, some data without T1 structural items were excluded from the data set. In addition, the quality of some data was too poor and the imaging was not clear enough. With a systematic quality assessment, only the available data were incorporated into the final experimental dataset (table S3), comprising 31 samples from Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients and 31 from healthy controls (CN) (Shown in Table 1).

The brain rs-fMRI signal was collected using the Philips Medical Systems Intera scanner with a magnetic field strength of 3 Tesla. The flip angle was set at 80.0°, with both Matrix X and Matrix Y being 64.0 pixels. The pixel spacing was 3.3 mm for both X and Y directions. In our work, a single scan of the data we collected will obtain 48 slices, and the original data has a total of 140 acquisition time points, so each sample consisted of 6720 slices with a slice thickness of 3.3 mm, an echo time (TE) of 30 ms, and a repetition time (TR) of 3001 ms, with a total of 140 time points collected.

In the preprocessing of rs-fMRI images, we used the DPABI (DPARSF5.4)20 tool in the MATLAB toolbox and selected parameters according to the standardized processing procedures. The first 10 time points were removed, and 24 head motion parameters were introduced to exclude signals from white matter and cerebrospinal fluid. Spatial smoothing was applied using a Gaussian kernel function with a full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of 4 mm. Band-pass filtering was performed within the range of 0.01–0.10 Hz to reduce the effects of head motion, physiological noise, and low-frequency drift. Additionally, during the registration process, manual adjustments were made to improve the accuracy of alignment, segmentation, and normalization, and the quality of the scanning images was rechecked. After preprocessing, each brain sample was represented as a 4D data matrix of 91 × 109 × 91 × 130, where the first three dimensions denote spatial information and the fourth dimension denotes temporal information.

Using the brain atlas defined by Shen et al.21, the rs-fMRI images were segmented into 268 ROIs, which were categorized into 8 functional groups. This study focuses on three ROI functional networks associated with AD: Frontoparietal22, Medial Frontal23, and Default Mode24,25,26. The Medial Frontal includes 29 ROIs, the Frontoparietal includes 34 ROIs, and the Default Mode includes 20 ROIs.

SNBG: single network based group

For each ROI, the voxel signals were averaged to obtain the mean BOLD time series corresponding to each ROI, denoted as b = (b1, b2, …, bL )T. Using.

a sliding window with a window size W (default 20) 27,28and a step size S, the BOLD time series was sliced to obtain K = 1 + (L-W)/S BOLD window sequences {x1, x2, …, xK}. Among them, the \({k}^{th}\) (k = 1, 2, 3, …, K) sequence is denoted as xk = \({({b}_{1+\left(k-1\right)S},{b}_{2+\left(k-1\right)S},\dots ,{b}_{W+(k-1)S})}^{T}\).

Let \({\mathbb{X}}=\left\{{\mathbf{x}}_{n,k,m}^{g}\left|g=\text{0,1};n=\text{1,2},\dots Ng;k=\text{1,2},\dots K;m=\text{1,2},\dots ,M\right.\right\}\) denote the signal data of K BOLD window sequences for M ROIs in Ng samples of group \({\mathbb{G}}^{g}\). If \({\mathbb{G}}^{0}\) represents the healthy control group and \({\mathbb{G}}^{1}\) represents the disease group, a ROI interaction network for each sample is constructed. In this network, the M ROIs serve as nodes, and the ROI-ROI relationships are represented as edges in the ROI network \({\mathbb{N}}=\{{\mathcal{N}}^{g,n,k}|g=\text{0,1};n=\text{1,2},\dots ,{N}_{g};k=\text{1,2},\dots ,K\}\), here \({\mathcal{N}}^{g,n,k}\) refers to the ROI interaction network for the \({k}^{th}\) window of the \({n}^{th}\) sample in the \({g}^{th}\) group, and the connectivity matrix of the network is \({\mathbf{E}}^{g,n,k}={\left({\text{e}}_{a,b}^{g,n,k}\right)}_{M\times M}\).

The concatenated signal for the \({a}^{th}\) ROI at the \({k}^{th}\) BOLD window of N0 samples in group \({\mathbb{G}}^{0}\) is denoted as sequence \({\widehat{\mathbf{x}}}_{k,a}^{{\mathbb{G}}^{0}}=({\mathbf{x}}_{1,k,a}^{0};{\mathbf{x}}_{2,k,a}^{0};...;{\mathbf{x}}_{{N}_{0},k,a}^{0})\), after including sample q from group \({\mathbb{G}}^{1}\),the new signal be denoted as \({\widehat{\mathbf{x}}}_{k,a}^{\left\{{\mathbb{G}}^{0},q\right\}}=\left({\widehat{\mathbf{x}}}_{k,a}^{{\mathbb{G}}^{0}};{\mathbf{x}}_{q,k,a}^{1}\right)\). The correlation between the ROI a and ROI b in the \({k}^{th}\) BOLD window for sample q in group \({\mathbb{G}}^{1}\) is calculated using Eq. (1):

where

Similarly, for each sample in the reference group \({\mathbb{G}}^{0}\),the group concatenated signals are computed by sequentially removing one sample. Specifically, the concatenated signal is calculated for the remaining N0-1 samples after removing a sample, and compared to the concatenated signal of the original N0 samples. This process allows for the computation of the sample network for each sample in the reference group (Fig. 1).

Network edge binarization and topological stability

The network connectivity is binarized using either absolute or proportional thresholding methods. The absolute thresholding method retains edges with absolute values exceeding a specified threshold, resulting in binarized networks with varying numbers of connections. The proportional thresholding method sets a soft threshold to retain a specified proportion of the edges in each network. Here, we select the commonly used α as the threshold for network stability analysis, retaining the top α of connections by strength.

To measure the network topology stability within the same group, node degree and global efficiency are chosen as the features for comparison. The relative standard deviation (RSD) is used to assess the stability of the topology, defined as Eq. (5):

and \({\mathbf{d}}^{g,n,k}= {({d}_{m}^{g,n,k})}_{M\times 1}\) is the feature vector of network \({\mathcal{N}}^{g,n,k}\). The RSD coefficient for the networks of K BOLD window sequences of the same sample is averaged and denoted as Eq. (7):

A smaller value of \(\overline{{\text{RSD} }_{m}^{g}}= \frac{{\sum }_{k=1}^{K}{\text{RSD}}_{m}^{g,k}}{K}\) indicates higher stability within the group.

Results and discussion

Comparison of network topological stability

Typically, there is a shared topological structure among individuals within the same group. However, due to noise affecting BOLD signals during data acquisition, there can be significant differences in brain functional network structures even among healthy individuals. Network modeling, which focuses on the relationships between ROIs, can effectively reduce noise interference. In this study, we compared the intra-group topological differences of sample brain networks under the aforementioned network modeling methods.

First, we assessed the stability of node degrees in the FPN, MFN, and DMN for both CN and AD group samples. The network binarization coefficient α was set at 15% which was recommended as keeping the topological structure of the brain network at the maximize level and filtering out most of the irrelevant connections29. Besides, we also tried other two threshold 10% and 20% (Supplementary Fig.S4 and Fig.S5). As shown in Table 2, in the DMN, the RSD values of nodes for single-sample networks constructed using the PCC-based method are higher compared to those using the SNBG method for both CN and AD groups. Consistent results were observed in the FP and MF functional group regions (as detailed in the supplementary materials Table S1 and Table S2). This indicates that networks constructed using the SNBG method exhibit greater stability, with more consistent local connections at the same node among samples within the group, leading to smaller differences between intra-group sample networks.

The global efficiency of a network is defined as the average of the inverse shortest paths30 between all pairs of nodes, which measures the efficiency of information transfer and overall connectivity of the network. As shown in Table 3, we calculated the RSD of global efficiency for networks constructed from 31 samples with both methods. The results indicate that networks constructed with the SNBG method exhibit more stable global topological features, further validating the method’s effectiveness in reducing intra-group differences.

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of global efficiency values across three networks in the CN group, the result of AD is presented in Fig. S3. As can be seen from Fig. 2, the global efficiency values obtained by the SNBG method in the three networks are more concentrated among the 31 samples. Considering the influence of the network binarization coefficient α on the results, we selected and compared the results of three different α, as shown in Figs. S3 and S4. It can be seen the global efficiency of the SNBG method almost all higher than that of the PCC-based method. Moreover, the results obtained based on the SNBG method are more compact with smaller within-group differences. Therefore, it can be demonstrated that the single-sample networks constructed using the SNBG method have higher global efficiency compared to those constructed using the PCC-based method, confirming the superiority of the SNBG method in network construction.

Connections between ROIs represent pathways for information exchange. As local ROIs deteriorate, associated connections may change, making network analysis crucial for studying neurodegenerative diseases. Here, we set the binarization threshold α to 15% and calculated the frequency of each edge’s occurrence across 31 sample networks in each group, using these frequencies as weights. Higher frequencies indicate more critical connections. Edges with frequencies above 0.5 were selected to create the network connection diagrams, as shown for the MFN in Fig. 3 (other networks are shown in the supplementary materials Figs. S1 and S2).

The connectivity diagram of the MFN, where the length of the arcs represents the proportion of the total frequency of connections between ROIs, and the width of the connecting edges indicates the proportion of the total frequency of those connections across the sample networks. (a) AD group by PCC-based method; (b) AD group by SNBG method; (c) CN group by PCC-based method and (d) CN group by SNBG method.

In both AD and CN groups, networks constructed using the SNBG method exhibited higher frequencies for key edges compared to those constructed using Pearson’s method, indicating greater stability in identifying network connections. Additionally, in the MFN, the connection frequency between dlPFC (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex)-R and dlPFC-L increased with the SNBG method. Previous studies have confirmed that the dlPFC is associated with AD31,32, demonstrating that our method can more precisely capture stable ROI connections related to AD.

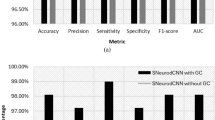

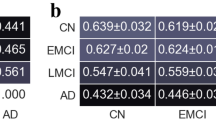

Comparison of differences between groups

Sample networks can effectively represent the associative patterns between individual ROIs, which is crucial for identifying disease-specific patterns. Here, we extract the clustering coefficient and node degree features from each sample network to construct classification models for the sample groups. We then compare the classification accuracy of models based on different network construction methods. For a more comprehensive analysis, we applied multiple proportion thresholds, ranking the edges by their weights and selecting the top α of the edges, with α ranging from 5 to 45% in increments of 5%, resulting in a total of 9 threshold sets. Each sample network was binarized using these 9 thresholds, and their topological features were calculated and concatenated. If a single threshold is used for classification, due to the incompleteness of the features, when comparing two different methods, the difference in the results is not significant enough. The results are shown in Supplementary Table S4 and Table S5. These features were then used to construct SVM models with a Gaussian kernel, and tenfold cross-validation was employed to compute the model’s prediction accuracy. The results are shown in Table 4.

For the DMN, FPN, MFN, and combined DMN + FPN + MFN groups, the classification accuracy of samples using the SNBG method is consistently higher than that of the PCC-based method, regardless of whether clustering coefficients or node degree features are used. Although the accuracy for both methods is relatively low when using clustering coefficients, our method still demonstrates superior intergroup classification performance. As shown in the Table 4, our method demonstrates superior classification performance across various network features. Specifically, when classifying features extracted from the combined DMN + FPN + MFN group, our method improves classification accuracy from 79.04 ± 5.41% to 83.52 ± 3.14%, and from 89.24 ± 3.11% to 97.13 ± 1.83%. To further verify the effectiveness of the classification results, we conducted 70% sampling for 50 times on the original two sets of data. We then spliced the network features of the DMN, MFN, and the FPN following the same steps and used the SVM for learning and classification. The results are shown in the Fig. 4. During the 50 rounds of cyclic experiments, the classification results based on the SNBG method were all higher than those based on the PCC-based network construction method.

The PCC-based method suffers from high intra-group variability in sample networks due to the significant influence of noise on BOLD signals, which negatively impacts intergroup classification performance. In contrast, the SNBG method, based on the group network of the healthy control group, effectively suppresses noise interference and extracts valid association patterns between ROIs, thus achieving better classification performance.

Conclusion

Using node degree and global efficiency as features for intra-group difference stability analysis, we found that the SNBG method exhibits superior stability in capturing ROI functional consistency, effectively reducing differences between samples within the group. This method significantly outperforms the PCC-based method in both local and global feature extraction. In classification, the SNBG method is more adept at identifying disease related network topological features, enhancing the extraction of sample category features. Both single-network features and combined network features demonstrate higher classification accuracy in SVM models. Overall, the proposed SNBG method reduces intra-group variability and achieves higher classification accuracy compared to the traditional PCC-based method, confirming its effectiveness. Additionally, SNBG can construct brain networks with more stable connections, which aids in uncovering potential connections related to the disease, offering new research perspectives for processing rs-fMRI data. However, our study has limitations, including a relatively small dataset and a broad age range among participants. Further research is needed to explore whether these methods can reveal more potential network features. Additionally, multimodal data such as demographic information, neuropsychological tests, and various AD biomarkers play a crucial role in AD diagnosis. Integrating multimodal data not only enhances the accuracy of AD diagnosis but also helps establish relationships between different modalities, providing valuable insights for clinical diagnosis and the investigation of disease mechanisms. Integrating fMRI single-sample network data with various multimodal datasets will be a key focus of our future research.

Data availability

All time-series data utilized in this study have been uploaded to GitHub: https://github.com/nohidenname/SNBG/tree/main/example%20data.

Code availability

The code used in the research has been uploaded to GitHub: https://github.com/nohidenname/SNBG

References

Teng, J., Mi, C., Shi, J. & Li, N. Brain disease research based on functional magnetic resonance imaging data and machine learning: A review. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1227491 (2023).

Wei, W. et al. Analyzing 20 years of resting-state fMRI research: trends and collaborative networks revealed. Brain Res. 1822, 148634 (2024).

Sang, F., Xu, K. & Chen, Y. Brain network organization and aging. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1419, 99–108 (2023).

Gu, Y. et al. Abnormal dynamic functional connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 26, 962–971 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Zhang, H., Chen, X., Lee, S. W. & Shen, D. Hybrid high-order functional connectivity networks using resting-state functional MRI for mild cognitive impairment diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 7, 6530 (2017).

Chen, P. et al. Altered global signal topography in Alzheimer’s disease. Ebiomedicine 89, 104455 (2023).

Cai, L. et al. Functional integration and segregation in multiplex brain networks for Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 14, 51 (2020).

Zhao, C. et al. Abnormal characterization of dynamic functional connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen Res. 17, 2014–2021 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Brain network construction and analysis for patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease based on a highly-available nodes approach. Brain Behav. 11, e02027 (2021).

Penalba-Sánchez, L., Oliveira-Silva, P., Sumich, A. L. & Cifre, I. Increased functional connectivity patterns in mild Alzheimer’s disease: A RsfMRI study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 1037347 (2023).

Chong, J. S. X. et al. Influence of cerebrovascular disease on brain networks in prodromal and clinical Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 140, 3012–3022 (2017).

Zhu, B. et al. Local brain network alterations and olfactory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease: An fMRI and graph-based study. Brain Sci. 13, 631 (2023).

Islam, J. & Zhang, Y. A novel deep learning based multi-class classification method for Alzheimer’s disease detection using brain MRI data. in Brain Informatics: International Conference, BI Beijing, China, November 16–18, 2017, Proceedings 213–222 (Springer, 2017).

Jiang, S., Feng, Q., Li, H., Deng, Z. & Jiang, Q. Attention based multi-task interpretable graph convolutional network for Alzheimer’s disease analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 180, 1–8 (2024).

Shan, X. et al. Spatial–temporal graph convolutional network for alzheimer classification based on brain functional connectivity imaging of electroencephalogram. Hum. Brain Mapp. 43, 5194–5209 (2022).

Cao, M., Halperin, J. M. & Li, X. Abnormal functional network topology and its dynamics during sustained attention processing significantly implicate post-TBI attention deficits in children. Brain Sci. 11, 1348 (2021).

Chen, H., Zhang, Y., Zhang, L., Qiao, L. & Shen, D. Estimating brain functional networks based on adaptively-weighted fMRI signals for MCI identification. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 595322 (2021).

Hutchison, R. M. et al. Dynamic functional connectivity: Promise, issues, and interpretations. Neuroimage 80, 360–378 (2013).

Rubinov, M. & Sporns, O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: Uses and interpretations. Neuroimage 52, 1059–1069 (2010).

Yan, C. G., Wang, X. D., Zuo, X. N. & Zang, Y. F. DPABI: Data processing & analysis for (resting-state) brain imaging. Neuroinformatics 14, 339–351 (2016).

Shen, X., Tokoglu, F., Papademetris, X. & Constable, R. T. Groupwise whole-brain parcellation from resting-state fMRI data for network node identification. Neuroimage 82, 403–415 (2013).

Badhwar, A. et al. Resting-state network dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 8, 73–85 (2017).

Cui, X. et al. Classification of Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, and normal controls with subnetwork selection and graph kernel principal component analysis based on minimum spanning tree brain functional network. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 12, 31 (2018).

Banks, S. J. et al. Default mode network lateralization and memory in healthy aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 66, 1223–1234 (2018).

Cai, S. et al. Altered functional brain networks in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: A resting-state fMRI study. Brain Imaging Behav. 11, 619–631 (2017).

Xue, C. et al. Distinct disruptive patterns of default mode subnetwork connectivity across the spectrum of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 11, 483881 (2019).

Ghanbari, M., Li, G., Hsu, L. M. & Yap, P. T. Accumulation of network redundancy marks the early stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum. Brain Mapp. 44, 2993–3006 (2023).

Zalesky, A. & Breakspear, M. Towards a statistical test for functional connectivity dynamics. Neuroimage 114, 466–470 (2015).

Hu, Q., Li, Y., Wu, Y., Lin, X. & Zhao, X. Brain network hierarchy reorganization in Alzheimer’s disease: A resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 43, 3498–3507 (2022).

Callow, D. D. & Smith, J. C. Physical fitness, cognition, and structural network efficiency of brain connections across the lifespan. Neuropsychologia 182, 108527 (2023).

Jones, D. T. & Graff-Radford, J. Executive dysfunction and the prefrontal cortex. Contin Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 27, 1586–1601 (2021).

Ma, S. et al. Molecular and cellular evolution of the primate dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Science 377, eabo7257 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82372087 and 82360363), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian province, China (2022Y0003), and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi province, China (20232BAB206136).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Y.K worte the main manuscript text, G.S , D.L.L and L.G.J edited the manuscript, D.J.Y reviewed the manuscript.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Gao, S., Deng, L. et al. A group based network analysis for Alzheimer’s disease fMRI data. Sci Rep 15, 10888 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95190-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95190-9