Abstract

Klotho, a protein primarily expressed in the kidneys and brain, plays a critical role in aging, vascular health, and various metabolic processes. Lower serum Klotho levels have been associated with several chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and kidney disease. Although the role of Klotho in platelet regulation remains underexplored, thrombocytosis may be influenced by Klotho levels. Investigating this relationship could offer new insights into thrombocytosis pathogenesis. This study aimed to examine the relationship between serum Klotho levels and thrombocytosis in a U.S. cohort. We hypothesized that lower Klotho levels would be associated with an increased risk of thrombocytosis, potentially providing a novel perspective on thrombocytosis regulation. We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data from 12,700 participants in the NHANES 2007–2016 cohort. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to assess the association between serum Klotho levels and thrombocytosis, adjusting for relevant covariates. Of the 12,700 participants, 86 had thrombocytosis. The thrombocytosis group had significantly lower mean serum Klotho levels compared to the non-thrombocytosis group (p < 0.01). After adjusting for confounders, an inverse association between serum Klotho levels and thrombocytosis was observed (odds ratio 0.89, 95% CI 0.82–0.97, p = 0.007). Compared to the lowest Klotho quartile (≤ 700.7 pg/ml), the adjusted odds ratios for thrombocytosis in the second (700.8-915.3 pg/ml) and third (≥ 915.4 pg/ml) quartiles were 0.6 (95% CI: 0.36–1.01, p = 0.055) and 0.49 (95% CI: 0.29–0.84, p = 0.01), respectively. Our findings suggest an inverse correlation between serum Klotho levels and thrombocytosis in adults aged 40 and older. These results highlight the potential role of Klotho in thrombocytosis regulation, and future longitudinal studies are needed to establish causality and explore the underlying mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thrombocytosis is a global condition caused by various pathogenic factors1. In recent years, there has been a notable increase in its incidence. Characterized by an elevated platelet count, thrombocytosis is often identified through abnormal results in routine blood tests, leading to frequent referrals to hematologists2. Thrombocytosis is a common hematologic disorder associated with various pathological conditions, including inflammation, infection, and malignancy. Thrombocytosis, marked by elevated platelet counts, poses several risks3. First, increased platelet levels raise blood viscosity, promoting clot formation and leading to complications like myocardial infarction, stroke, and pulmonary embolism, which can be life-threatening4,5. Second, excessive platelets may cause dysfunction, paradoxically increasing bleeding risks, especially in the skin, mucous membranes, and gastrointestinal tract5. Lastly, endothelial damage may trigger systemic inflammation, potentially impairing vital organs such as the kidneys and liver6. Thrombocytosis is commonly categorized into essential thrombocythemia (ET) and secondary thrombocytosis2.

Primary thrombocytosis is frequently linked to myeloproliferative disorders like essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera. These conditions are often driven by genetic mutations, such as those in the JAK2, CALR, or MPL genes, which interfere with the regulation of platelet production5. Secondary thrombocytosis can arise from various factors, including infections, chronic inflammatory diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease), iron deficiency anemia, and stress responses following surgery or trauma, as well as certain malignancies. These factors can stimulate the bone marrow, resulting in an overproduction of platelets3,7. An increase in platelet count is associated with various factors, but it is often challenging to pinpoint the exact cause. Previous studies have revealed that 70% of thrombocytosis cases are secondary, while the precise etiology remains unclear8.

Alpha-klotho, also referred to as klotho, is a multifunctional protein encoded by the klotho gene9. Klotho is a multifunctional protein that plays a critical role in various physiological processes, including metabolism, aging, and mineral homeostasis10,11,12. It exists in both a membrane-bound form and a secreted form, the latter of which has been identified as a hormone influencing diverse cellular functions13. Klotho is essential for regulating calcium and phosphate metabolism, acting as a co-factor for fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), which lowers serum phosphate levels and inhibits renal phosphate reabsorption14. Moreover, it is often referred to as an “anti-aging” gene due to its association with increased lifespan in animal models, while lower levels of Klotho have been linked to age-related diseases15,16,17. Klotho also exerts protective effects on cardiovascular health by reducing vascular calcification and inflammation17. In the context of hematopoiesis, emerging research suggests that Klotho may influence hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) function, impacting their proliferation and differentiation18,19. Additionally, Klotho may interact with signaling pathways related to thrombopoietin (TPO), potentially modulating platelet production and affecting megakaryocyte function. Lan et al.20. found renal Klotho as a long-range regulator of platelet lifespan, shedding light on the molecular mechanisms underlying CKD-associated thrombocytopenia and hemorrhage, while also presenting a promising therapeutic avenue. Overall, Klotho is a significant regulatory protein whose diverse functions warrant further investigation to fully elucidate its roles in hematopoiesis and platelet production.

The relationship between serum Klotho levels and thrombocytosis in middle-aged and older adults remains poorly understood. We hypothesize that lower serum Klotho levels are associated with an increased risk of thrombocytosis in middle-aged and older adults, potentially mediated by mechanisms such as endothelial dysfunction, increased oxidative stress, and systemic inflammation—all of which play critical roles in platelet production and activation. In older adults, age-related physiological changes may disrupt Klotho-mediated regulatory pathways, leading to elevated platelet counts. Additionally, as organ function declines with age, particularly in the kidneys—the primary site of Klotho synthesis and secretion—serum Klotho levels decrease. This reduction may contribute to an imbalance in platelet homeostasis, further linking Klotho deficiency to thrombocytosis. Rather than focusing solely on individual symptoms, understanding how variations in serum Klotho levels influence different manifestations of thrombocytosis holds greater clinical significance. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the clinical and prognostic relevance of serum Klotho in middle-aged and older adults with thrombocytosis. To address this gap, we conducted a cross-sectional study utilizing data from 12,700 participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Methods.

Study population.

This cross-sectional study used data from the 2007–2016 NHANES, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention21. NHANES aimed to assess the health and nutritional status of non-institutionalized Americans. Survey participants were selected based on a stratified probability design using a multistage process22. NHANES collects various health-related data, including demographic characteristics, physical examination results, laboratory findings, and dietary habits23. The National Center for Health Statistics collected the information following ethics review board approval. All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the NHANES22. The data are publicly available at the NHANES website (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm). Participants between the ages of 40 and 79 from NHANES 2007–2016 cycles were included in the study (n = 12,700). Serum Klotho concentrations were only measured in this specific age group and cycles.

Pregnant females and individuals who lacked information about serum klotho, CBC, covariates, or weight were excluded. Data on demographics, physical examinations, and laboratory tests were gathered during in-home interviews and study visits conducted at a mobile examination center (MEC)21. Medication use was obtained through the interviewer’s observation of individual’s prescription medications.

Serum Klotho levels.

Serum Klotho concentrations were measured by a commercial ELISA kit (IBL International, Japan). As per the manufacturer’s instructions, the analysis of each sample was carried out twice, and the average of the two results was used as the final value. Each plate was analyzed with two quality control samples containing low and high concentrations of Klotho to ensure accuracy. Sample analyses were repeated when the assigned value of a quality control sample exceeded two standard deviations. The sensitivity of the assay was 4.33 pg/mL, with both the intra-assay and inter-assay coefficient of variation was under 5%. The detail description of laboratory methodology is available on the website at https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2007-2008/ SSKL_E. htm.

Platelet level and thrombocytosis assessment.

Blood counts, including platelet counts, were measured using Beckman Coulter Counter (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA, USA). Thrombocytosis is defined as a single platelet count > 450 × 10^9/L, based on the WHO diagnostic criteria for thrombocytosis4.

Covariates.

During the household interview, the computer-assisted personal interviewing system was used to collect sociodemographic data including age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, smoking status, and medical conditions. Self-reported race/ethnicity was classified into non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, Mexican American, and other race (including multi-racial and other Hispanic group). Educational achievement was divided into three categories: did not complete high school, graduate high school or obtained a General Educational Development (GED) certificate, and attended college or beyond. Income levels were categorized into three tiers based on the family’s income-to-poverty ratio (IPR): less than 1.30, 1.30 to 3.49, or 3.50 or greater. The smoking status was divided into three categories: never smokers, former smokers, and current smokers (those who have smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and continue to smoke). The alcohol questionnaire is administered during the physical exam at the MEC. The drinking status was classified into three categories: never drinkers, former drinkers, and current drinkers (who have consumed at least 12 alcoholic beverages in their lifetime and still continue to consume alcohol).

Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥ 140mmHg, DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg, a self-reported physician diagnosis, or currently taking antihypertensive medications24. Diabetes mellitus was defined as hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%, fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, random plasma glucose or 2 h plasma glucose (oral glucose tolerance test) ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, a self-reported physician diagnosis, or current use of antidiabetic medications or insulin25.

Statistical analysis

Histogram distribution, Q-Q plot, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test were employed to evaluate the normality of study variables. Normally distributed continuous variables were summarized as mean ± SD, whereas skewed continuous variables were shown as median (interquartile range [IQR]). Categorical variables were represented as frequencies and percentages. Statistical analyses included chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables, One-Way ANOVA for normally distributed continuous variables, and Kruskal-Wallis H test for skewed continuous variables to compare differences among various klotho groups.

A multivariate logistic regression model was used to assess the association between serum Klotho levels and thrombocytosis. Covariates were selected based on prior literature, clinical relevance, univariate analysis (p < 0.10), and collinearity diagnostics (VIF < 10). The final model included demographic factors (age, sex, race), lifestyle variables (smoking, alcohol consumption, BMI), hematologic markers (hemoglobin, white blood cell count), metabolic factors (phosphate, vitamin D), kidney function indicators (creatinine), and comorbidities (cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes). Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. Model robustness was assessed through collinearity diagnostics and model fit criteria, including the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and AIC/BIC comparisons. Four models were constructed for the analysis: Model 1 adjusted for age, and Model 2 included additional adjustments for race/ethnicity, marital status, poverty-income ratio (PIR) and education level. Model 3 further adjusted for smoking status, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, coronary heart disease, and body mass index. Model 4 further adjusted for hemoglobin, white blood cell count, phosphate, 25(OH)D and creatinine.

All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (Version 4.2.2, http://www.R-project.org, The R Foundation) and Free Statistics Analysis Platform (Version 1.9.2, Beijing, China, http://www.clinicalscientists.cn/freestatistics). The Free Statistics Analysis Platform is a user-friendly software package for common analyses and data visualization, leveraging R as the statistical engine and a graphical user interface (GUI) developed in Python. Most analyses can be executed with minimal effort, making it suitable for reproducible analysis and interactive computing. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the research sample

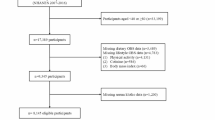

The present study used data from five NHANES periods (2007–2008, 2009–2010, 2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016). A total of 50,588 participants completed the survey. A total of 37,888 individuals were excluded, including 36,824 individuals with missing serum Klotho data, 40 individuals with missing complete blood count (CBC) data, 9 pregnant females and 1,015 individuals with missing demographic data. Thus, 12,700 participants were included in this study (Fig. 1).

A total of 12,700 participants with available data on serum Klotho and thrombocytosis were included in the analysis and 86 participants (0.7%) suffered from thrombocytosis. Table 1 presents the clinical and biochemical features of the study population based on Klotho levels. The mean age of participants was 57.9 ± 10.8 years, with 6,207 (48.9%) being men. Most participants self-identified as non-Hispanic White (5,610, 44.2%). Participants with higher Klotho concentrations had higher hemoglobin levels and were more likely to have a history of cardiovascular disease (CVD), coronary heart disease, stroke, and hypertension. Additionally, they were more likely to have never smoked and not consumed alcohol.

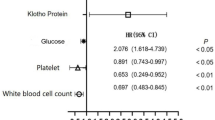

Associations between serum Klotho and thrombocytosis

An inverse association between serum klotho and thrombocytosis was observed after adjusting for potential confounders (Table 2). Multivariate logistic regression analysis, adjusted for potential confounders, revealed that each 100 pg/ml increase in serum Klotho levels was associated with a 11% decrease in the risk of thrombocytosis (95% CI = 0.82 ~ 0.97, P = 0.007) (Table 2, model 3). Compared to individuals in the lowest quartile (Q1) of serum klotho (≤ 700.7 pg/ml), the adjusted ORs for thrombocytosis in Q2(700.8915.3 pg/ml), and Q3 (≥ 915.4 pg/ml), were 0.6 (95% CI: 0.36–1.01, p = 0.055), and 0.49 (95% CI: 0.29–0.84, p = 0.01) respectively.

Subgroup analysis

In our study, we conducted subgroup analyses to explore whether the relationship between serum Klotho levels and thrombocytosis varies across different demographic and clinical characteristics. Stability tests were performed on the results using subgroup analyses (Fig. 2) and interaction testing, but no significant interactions were observed. These subgroup analyses were based on factors such as age, gender, body mass index (BMI), education level, smoking, alcohol consumption, cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension, and diabetes. Overall, consistent trends were observed in most subgroups. We divided participants into two age groups: middle-aged individuals (40–60 years) and older adults (> 60 years). The association between Klotho levels and thrombocytosis was somewhat more apparent in the middle-aged group, suggesting that age-related changes in Klotho metabolism may influence platelet regulation. In the female subgroup, a significant correlation was found, with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.78–0.95), indicating that lower serum Klotho levels are associated with an increased risk of thrombocytosis in women. In contrast, no significant association was found in the male subgroup, suggesting that the relationship between Klotho and thrombocytosis may be more pronounced in women, potentially due to hormonal and physiological differences between genders. Among participants with cardiovascular disease and diabetes, lower Klotho levels were more strongly associated with thrombocytosis, suggesting that Klotho may play a critical role as a regulator in individuals with chronic inflammation. Additionally, a correlation between Klotho and thrombocytosis was observed among smokers and drinkers, further supporting the consistency of the results across these lifestyle factors.

The relation of serum Klotho concentration with the prevalence of thrombocytosis in various subgroups. Adjusted for sociodemographic (age, sex, marital status, race/ethnicity, education level, family income), smoking status, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, coronary heart disease, body mass index, if not stratified.

Discussion

Utilizing data from 12,700 participants aged 40 and older in the NHANES (2007–2016) dataset, this study is the first cross-sectional analysis to examine the relationship between serum Klotho levels and thrombocytosis in a nationally representative adult population. Our study demonstrated a significant inverse association between serum Klotho levels and thrombocytosis in middle-aged and older adults. Individuals with lower serum Klotho concentrations were more likely to present with thrombocytosis, and this association remained robust after adjusting for multiple confounders, including age, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and comorbid conditions such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes. Although we adjusted for major demographic, hematologic, metabolic, and comorbid conditions, residual confounding cannot be ruled out. Future studies with more comprehensive biomarker data may help further clarify these relationships. Subgroup analyses further confirmed the robustness of this association across various demographic and clinical groups. Notably, the inverse relationship between Klotho levels and thrombocytosis was more pronounced in females, while no significant association was observed in males. This suggests a potential sex-specific regulatory role of Klotho in platelet homeostasis, warranting further investigation. Given Klotho’s established involvement in endothelial function, oxidative stress reduction, and anti-inflammatory processes, our findings provide novel insights into its potential role in thrombocytosis. However, further mechanistic studies are needed to elucidate the exact pathways through which Klotho influences platelet production and activation.

Currently, there is limited research on the relationship between Klotho and platelet levels. The Klotho gene was initially identified as a potential anti-aging gene9, with its overexpression extending lifespan and its deficiency accelerating aging26. The Klotho protein is involved in a wide range of physiological and pathological processes, playing a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis. Klotho is a co-receptor for fibroblast growth factor (FGF), which is involved in maintaining homeostasis of the endocrine system and plays a key role in vascular health and homeostasis27. The regulatory effects of Klotho on platelet production and activation may be mediated through multiple biological pathways, primarily by modulating oxidative stress and calcium signaling. Klotho proteins play a crucial role in regulating platelet activity and endothelial function through multiple biological pathways. They have been shown to reduce platelet overactivation induced by the uremic toxin indole sulfate (IS) by inhibiting reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and the p38MAPK signaling pathway28. In Klotho-deficient mice, the calcium signaling pathway is disrupted, as evidenced by the reduced expression of calcium release-activated calcium channels (CRACs) and their regulator STIM1/Orai1. This inhibition is partly attributed to the downregulation of NF-κB activity by 1,25(OH)₂ vitamin D₃, which subsequently affects platelet and megakaryocyte functions29. Klotho proteins are essential for maintaining endothelial integrity and preventing endothelial dysfunction, both of which are critical for inhibiting platelet overactivation and thrombocytosis. They significantly enhance the antioxidant capacity of endothelial cells and mitigate oxidative stress and inflammation by regulating the PI3K/AKT/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, thereby protecting endothelial cells from oxidative damage30,31. Additionally, Klotho regulates calcium influx, preserves endothelial cell integrity, and prevents endothelial apoptosis and hyperpermeability by interacting with VEGF receptor-2 and TRPC-1 calcium channels32. Furthermore, Klotho inhibits excessive proliferation of vascular endothelial cells and maintains normal vascular structure by modulating the AMPK and YAP signaling pathways33. Through these diverse mechanisms, Klotho proteins play a pivotal role in enhancing endothelial integrity and suppressing endothelial dysfunction, thereby contributing to the prevention of platelet overactivation and thrombocytosis. Due to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, Klotho may regulate platelet homeostasis in vivo by mitigating systemic inflammation and reducing oxidative stress-induced platelet hyperactivity. Klotho influences platelet generation and function by modulating calcium signaling and counteracting the effects of uremic toxins like indoxyl sulfate. This highlights its potential therapeutic role in managing platelet-related complications, especially in CKD.

A significant finding of our study is that the inverse association between Klotho levels and thrombocytosis was more pronounced in females, whereas no significant relationship was observed in males. This sex difference may be attributed to several biological mechanisms. A significant relationship exists between estrogen and Klotho expression. Estrogen regulates Klotho expression and has a protective effect on endothelial function. Research has shown that estrogen regulates Klotho gene expression, which plays a crucial role in various physiological and pathological processes34. In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), Klotho expression was positively correlated with estrogen receptor (ER)α expression, suggesting that Klotho may partially regulate the estrogenic pathway mediated through Erα35. Sex differences in immune responses may contribute to the observed variations in Klotho’s effects on thrombocytosis. Women generally exhibit a stronger immune response and higher baseline levels of inflammation than men36. Given Klotho’s anti-inflammatory properties, its deficiency may have a more pronounced impact on platelet overproduction in females17, further strengthening the observed inverse association. Klotho has been reported to exert antioxidant effects through the PI3K/AKT/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, reducing oxidative stress and preserving endothelial function37. Given that women are more vulnerable to oxidative stress-related damage due to hormonal fluctuations, the protective role of Klotho may be more pronounced in females38, potentially contributing to the stronger association observed in our study. Sex-based differences in platelet production may further explain the stronger association observed in females. Ranucci, M. et al.39showed that women typically have higher baseline platelet counts than men, which may enhance the regulatory role of Klotho in platelet homeostasis. The stronger inverse association between Klotho levels and thrombocytosis in females may be attributed to multiple biological mechanisms. Estrogen-mediated upregulation of Klotho expression, sex-specific differences in immune response and oxidative stress susceptibility, and inherent variations in platelet production may all contribute to this observed discrepancy. Further research is needed to elucidate these mechanisms and explore the potential clinical implications of Klotho-based interventions in thrombocytosis.

As a potential therapeutic target, Klotho may offer several advantages. Its ability to regulate platelet activity through various signaling pathways, such as ROS/p38MAPK, positions it as a key modulator in inflammatory conditions that often lead to platelet overactivation28. Additionally, Klotho supplementation or gene therapy could be explored as a means to restore its function in individuals with Klotho deficiency, potentially offering a novel approach to managing thrombocytosis, particularly in patients with underlying conditions such as chronic kidney disease, atherosclerosis, or cardiovascular disease. Future studies are needed to validate the feasibility of Klotho as a therapeutic target for thrombocytosis. These studies should focus on its ability to modulate platelet activity and assess its efficacy in reducing thrombotic events in animal models and human clinical trials. Moreover, exploring the potential of Klotho in combination with other treatments, such as anti-platelet therapies or inflammation-modulating drugs, could provide a more comprehensive therapeutic strategy for patients with thrombocytosis and related conditions. Klotho holds promise as a therapeutic target for thrombocytosis, particularly in patients with conditions that exacerbate platelet activation. Continued research into its mechanisms of action and clinical application will be essential in determining its viability as a treatment option for platelet-related disorders.

This study utilized a single platelet count measurement to define thrombocytosis. However, we acknowledge that this approach may not fully reflect the true nature of thrombocytosis, especially since thrombocytosis can be transient or fluctuate, particularly when influenced by other clinical factors such as infection or stress. As a result, relying on a single measurement may introduce some risk of misclassification. To more accurately assess thrombocytosis, future studies could consider using multiple platelet count measurements or adopt criteria such as sustained elevation to define thrombocytosis. This would help reduce the potential for misclassification and provide a more robust reflection of the true state of thrombocytosis, thereby allowing a more precise examination of the relationship between Klotho levels and thrombocytosis. However, due to the limitations of the current dataset, we were unable to implement multiple measurements, and we acknowledge this as a limitation in the present study. This limitation should be addressed in future longitudinal research.

Strengthen and limitation

Due to the limitations of the cross-sectional design and the observed number of related events, this study cannot clearly establish a causal relationship between thrombocytosis and serum Klotho levels. The absence of data on Klotho levels in younger populations further underscores the need for additional clinical trials. Moreover, based on the current research, it remains difficult to distinguish whether thrombocytosis is of primary or secondary origin. This limitation hinders a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between thrombocytosis and serum Klotho levels, as well as the development of targeted research and treatment strategies, which should be addressed in future studies. Although most subgroup analyses yielded p-values below 0.05, some comparisons (e.g., Q2) resulted in borderline p-values (e.g., 0.073). While these do not meet the conventional threshold for statistical significance, the consistent trends observed across multiple models support the robustness of the findings. Future studies with larger sample sizes may help clarify these marginal associations. Additionally, due to the limitations of the NHANES dataset, we were unable to include certain important confounders, such as inflammatory markers (e.g., CRP, ferritin), which may affect both Klotho levels and platelet counts. Despite controlling for several relevant covariates, residual confounding remains a possibility. Furthermore, the lack of longitudinal data prevented us from exploring how changes in Klotho levels over time influence thrombocytosis. Future studies incorporating repeated measurements or longer follow-up periods will be crucial for understanding how Klotho levels fluctuate and affect platelet regulation over time. Despite these limitations, the consistent trends observed across different models offer valuable insights into the relationship between Klotho levels and thrombocytosis.

However, the main strength of our study is the robust evidence on the association of serum Klotho levels with thrombocytosis based on a nationally representative and noninstitutionalized US civilian population. The NHANES is a large-scale study that employs standardized study protocols, strict quality control metrics, and well-trained specialized technicians to collect and process data. Our research discovered a negatively association between serum Klotho levels and thrombocytosis, independent of other confounding factors, including such as educational level, race, BMI, smoking status, alcohol intake, history of CVD and hypertension. All adjusted models confirmed the robustness of this association.

Conclusion

Our study found an inverse association between serum Klotho levels and thrombocytosis in adults aged 40 and older. However, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, this association does not imply causality. Future longitudinal studies and clinical trials are necessary to assess the causal relationship and explore the mechanisms underlying this association.

Data availability

The data used in this study are publicly available from the NHANES database, which can be accessed through the NHANES website. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data used in this study is available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). You can access the data sets by visiting the NHANES website: URL: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx.

Abbreviations

- Klotho:

-

α-Klotho

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- FGF23:

-

Fibroblast growth factor 23

- HSC:

-

Hematopoietic stem cells

- NCHS:

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- PIR:

-

Poverty income ratio

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- METs:

-

Metabolic equivalents

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- Hb:

-

Hemoglobin

- EPO:

-

Erythropoietin

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

References

Schafer, A. I. Thrombocytosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 1211–1219 (2004).

Larsson, A. E., Andréasson, B., Holmberg, H., Liljeholm, M. & Själander, A. Erythrocytosis, thrombocytosis, and rate of recurrent thromboembolic event-a population based cohort study. Eur. J. Haematol. 110, 608–617 (2023).

Tefferi, A. & Barbui, T. Polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: 2021 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification and management. Am. J. Hematol. 95, 1599–1613 (2020).

Harrison, C. N. et al. Guideline for investigation and management of adults and children presenting with a thrombocytosis. Br. J. Haematol. 149, 352–375 (2010).

Tefferi, A. & Pardanani, A. Essential thrombocythemia. N Engl. J. Med. 381, 2135–2144 (2019).

Vainchenker, W. & Kralovics, R. Genetic basis and molecular pathophysiology of classical myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood 129, 667–679 (2017).

Vannucchi, A. M. & Barbui, T. Thrombocytosis and thrombosis. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program. 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.363 (2007).

Tremblay, D., Alpert, N., Taioli, E. & Mascarenhas, J. Prevalence of unexplained erythrocytosis and thrombocytosis – an NHANES analysis. Leuk. Lymphoma. 62, 2030–2033 (2021).

Kuro-o, M. et al. Mutation of the mouse Klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature 390, 45–51 (1997).

Akhiyat, N. et al. Patients with coronary microvascular dysfunction have less circulating α-klotho. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 13, e031972 (2024).

Wang, Y., Hu, B. & Yang, S. Association between serum Klotho levels and hypothyroidism in older adults: NHANES 2007–2012. Sci. Rep. 14, 11477 (2024).

Xiao, Y., Hou, Y., Zeng, J., Gong, Y. & Ma, L. Association between the serum α-klotho level and insulin resistance in adults: NHANES 2007–2016. Endocr. Res. 49, 145–153 (2024).

Xu, Y. & Sun, Z. Molecular basis of Klotho: from gene to function in aging. Endocr. Rev. 36, 174–193 (2015).

Agoro, R. & White, K. E. Regulation of FGF23 production and phosphate metabolism by bone-kidney interactions. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 19, 185–193 (2023).

Buchanan, S., Combet, E., Stenvinkel, P. & Shiels, P. G. Klotho, aging, and the failing kidney. Front. Endocrinol. 11, 560 (2020).

Kuro-o, M. Klotho as a regulator of fibroblast growth factor signaling and phosphate/calcium metabolism. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 15, 437–441 (2006).

Prud’homme, G. J. & Wang, Q. Anti-Inflammatory role of the Klotho protein and relevance to aging. Cells 13, 1413 (2024).

Vadakke Madathil, S., Coe, L. M., Casu, C. & Sitara, D. Klotho deficiency disrupts hematopoietic stem cell development and erythropoiesis. Am. J. Pathol. 184, 827–841 (2014).

Du, C. et al. Renal Klotho and inorganic phosphate are extrinsic factors that antagonistically regulate hematopoietic stem cell maintenance. Cell. Rep. 38, 110392 (2022).

Lan, Q. et al. Renal Klotho safeguards platelet lifespan in advanced chronic kidney disease through restraining Bcl-xL ubiquitination and degradation. J. Thromb. Haemost JTH. 20, 2972–2987 (2022).

Akinbam, L. et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2017–March 2020 Prepandemic File: Sample Design, Estimation, and Analytic Guidelines. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/115434https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc:115434 (2022).

Zipf, G. et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Plan and Operations, 1999–2010. Vital Health Stat. Ser 1 Programs Collect1–37 (Proced, 2013).

Liu, H., Wang, Q., Dong, Z. & Yu, S. Dietary zinc intake and migraine in adults: a cross-sectional analysis of the National health and nutrition examination survey 1999–2004. Headache J. Head Face Pain. 63, 127–135 (2023).

Bakris, G., Ali, W. & Parati, G. ACC/AHA versus ESC/ESH on hypertension guidelines: JACC guideline comparison. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73, 3018–3026 (2019).

Cosentino, F. et al. 2019 ESC guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur. Heart J. 41, 255–323 (2020).

Ullah, M. & Sun, Z. Klotho deficiency accelerates stem cells aging by impairing telomerase activity. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 74, 1396–1407 (2019).

Kanbay, M. et al. Role of Klotho in the development of essential hypertension. Hypertens. Dallas Tex. 1979. 77, 740–750 (2021).

Yang, K. et al. Indoxyl sulfate induces platelet hyperactivity and contributes to chronic kidney disease-associated thrombosis in mice. Blood 129, 2667–2679 (2017).

Borst, O. et al. 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3-dependent Inhibition of platelet Ca2 + signaling and thrombus formation in klotho-deficient mice. FASEB J. Off Publ Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 28, 2108–2119 (2014).

Cui, W., Leng, B. & Wang, G. Klotho protein inhibits H2O2-induced oxidative injury in endothelial cells via regulation of PI3K/AKT/Nrf2/HO-1 pathways. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 97, 370–376 (2019).

Yao, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Liu, C. Klotho ameliorates oxidized low density lipoprotein (ox-LDL)-induced oxidative stress via regulating LOX-1 and PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathways. Lipids Health Dis. 16, 77 (2017).

Kusaba, T. et al. Klotho is associated with VEGF receptor-2 and the transient receptor potential canonical-1 Ca2 + channel to maintain endothelial integrity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 107, 19308–19313 (2010).

Luo, L., Guo, J., Li, Y., Liu, T. & Lai, L. Klotho promotes AMPK activity and maintains renal vascular integrity by regulating the YAP signaling pathway. Int. J. Med. Sci. 20, 194–205 (2023).

Tan, Z. et al. Klotho regulated by Estrogen plays a key role in sex differences in stress resilience in rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 1206 (2023).

Huang, S., Wang, W., Cheng, Y., Lin, J. & Wang, M. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of Klotho and Estrogen receptors expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. Off J. Turk. Soc. Gastroenterol. 32, 828–836 (2021).

Mathad, J. S. et al. Sex-related differences in inflammatory and immune activation markers before and after combined antiretroviral therapy initiation. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 73(2), 123–129 (2016).

Wen, X. et al. Recombinant human Klotho protects against hydrogen peroxide-mediated injury in human retinal pigment epithelial cells via the PI3K/Akt-Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Bioengineered 13, 11767–11781 (2022).

Wu, S. E. & Chen, W. L. Soluble Klotho as an effective biomarker to characterize inflammatory States. Ann. Med. 54, 1520–1529 (2022).

Ranucci, M. et al. Gender-based differences in platelet function and platelet reactivity to P2Y12 inhibitors. PloS One. 14, e0225771 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for providing the data used in this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Education Foundation of Jilin Province of China (Grant No. JJKH20211193KJ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YQ served as the first author and was responsible for the conception and design of the study, data collection, and statistical analysis. YQ also took the lead in drafting the manuscript and interpreting the results. MJB played a key role in the acquisition and processing of data, contributed to the statistical analysis, and was involved in the interpretation of the findings. MJB also provided critical revisions to the manuscript. MZM contributed to the study design, provided expertise in the biochemical assays, and assisted in data interpretation. MZM also reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. SG, as the corresponding author, supervised the entire project, including the study design and execution. SG provided significant intellectual input and was responsible for the final approval of the manuscript before submission. Additionally, SG handled all correspondence and communication with the journal.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

All authors consent to the submission and publication of this manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research conducted using NHANES data complies with ethical standards and guidelines. Although NHANES data are publicly available and do not require individual informed consent, the analysis of these data was performed in accordance with ethical principles for research involving human subjects. Specifically, this study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, which provides guidelines for conducting research with respect for the rights and welfare of participants.

Ethics and consent statement

All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines, ensuring that participants were fully informed about their rights and the purpose of the research. The computer-assisted personal interviewing system was utilized during the household interview to collect sociodemographic data, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, smoking status, and medical conditions. Prior to participation, individuals were fully informed about the purpose of the household interview and the use of the computer-assisted personal interviewing system for data collection. Informed consent was obtained from all participants to ensure they understood their rights and the confidentiality of their responses.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, Q., Ma, J., Ma, Z. et al. Association between serum Klotho levels and thrombocytosis in aging adults based on evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Sci Rep 15, 10763 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95241-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95241-1