Abstract

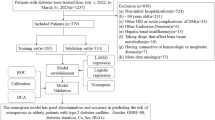

Hemodialysis patients (HD) frequently experience nausea and vomiting as side effects, which can make the procedure uncomfortable for them and cause it to end too soon. There are no known predictors of vomiting. We aim to create a nomogram that can anticipate vomiting in hemodialysis patients. We conducted a retrospective screening of patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who received regular hemodialysis at the First People’s Hospital of Nantong from January 1, 2023, to October 31, 2024. The outcome of the nomogram indicated vomiting, which was evaluated using the Korttila scale. The least absolute shrinkage selection operator (LASSO) method and Boruta feature selection were employed for the optimal prediction of predictors. Multiple logistic regression was employed to construct predictive models presented as nomograms. The efficacy of nomograms was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, calibration plots, and decision curve analysis (DCA). The model underwent internal validation by assessing the validation cohort’s performance. The study included 281 patients. Ninety-two patients, representing 32.74%, exhibited symptoms of vomiting. Participants were randomly assigned to training (n = 196) and validation (n = 85) groups. The nomogram incorporated predictors such as sex, height, heart rate, spKt.V, lymphocytes, and lactate dehydrogenase. The ROC curves for both the training and verification groups demonstrate strong recognition capability, while the calibration curves indicate that the correction outcomes for both groups are highly satisfactory. This nomogram assists clinicians in identifying high-risk populations and supports the formulation of effective preventive strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hemodialysis is the predominant form of renal replacement therapy for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients. It constitutes roughly 89% of all dialysis cases1,2,3. In 2018, a survey report encompassing 182 national populations indicated that the median hemodialysis utilization was 298.4 per million4. Patients undergoing hemodialysis may encounter a range of complications, such as hypotension, muscle cramps, imbalance syndrome, nausea and vomiting, and dyspnea. Nurses need to be well-acquainted with these complications. Preventing complications is crucial. Timely identification and management of critical complications can preserve patient life. Certain complications associated with hemodialysis do not pose an immediate threat to patient survival; however, an increase in intradialytic symptoms correlates with adverse outcomes, such as diminished quality of life, lower dialysis dosage, depression, and increased mortality5,6. Addressing these issues may prolong a patient’s lifespan and enhance the quality of life.

Nausea and vomiting represent prevalent complications associated with hemodialysis. Chong and Tan’s study examined the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms among Asian patients undergoing conventional hemodialysis, revealing a significant occurrence of anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and early satiety during meals. This study reported an incidence of nausea at 18.2% and vomiting at 9.8%7. In a study conducted in Iran, the incidence of nausea and vomiting during hemodialysis was found to be higher, with symptoms reported in up to 25.8% of cases8. Nausea and vomiting following the initiation of hemodialysis can arise from multiple factors7,9. Since nausea and vomiting cause problems for hemodialysis patients, they should be looked into further and avoided. Dehydration, or an imbalance in electrolytes and water, can be a severe consequence of vomiting. Even though dialysis is expensive, nausea and vomiting make it unpleasant for the patient and may cause them to stop it early, which can contribute to poor dialysis results10. For doctors to anticipate vomiting, a model must be developed. According to this paradigm, medical professionals are aware of the likelihood that a patient would experience excessive vomiting and take appropriate action.

There is currently a dearth of information evaluating the risk factors for vomiting in hemodialysis patients. Machine learning algorithms have been used more often in recent years to create prediction models as artificial intelligence has grown11. We believe that non-variable screening models are inappropriate for clinical practice, have significant computing costs during operation and subsequent maintenance, and are not very repeatable in various healthcare contexts. Also, given the high dimensionality of the data, we chose to use LASSO first for preliminary screening to reduce Boruta ‘s computational burden and to improve the efficiency of the overall analysis. Thus, after screening out risk factors using LASSO regression. we further screened variables using the Boruta feature screening method. We then iteratively processed random fluctuations in forest importance scores and factor interactions to screen for significant vomiting predictors. This approach is often employed in Diabetes Mellitus (DM) research for feature selection12,13. In addition, Zirui Meng et al. constructed a predictive model for severe novel coronavirus pneumonia using variant analysis and modeling with the least absolute contraction and selection operator (LASSO) and Boruta algorithm14. Xuexuan Ding et al. used five machine learning algorithms, LASSO, SVM-RFE, Boruta, XGBoost, and RF, to identify core genes in asthma15.

This study aimed to gather clinical data from adult hemodialysis patients to create a prediction model for vomiting based on machine learning algorithms and to determine the main variables influencing vomiting. With this technology, medical professionals will be able to recognize high-risk populations and take early action to enhance their quality of life.

Patients and methods

Study design and participants

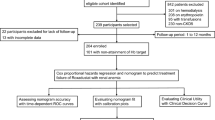

We conducted a retrospective analysis of a group of hemodialysis patients admitted to the First People’s Hospital of Nantong’s nephrology ward between January 1, 2023, and October 31, 2024. For an average of three to four hours, each patient had dialysis thrice weekly. Criteria for inclusion: (1) between the ages of 18 and 80; (2) maintenance hemodialysis lasting more than three months; (3) completing hemodialysis therapy with an arteriovenous fistula; (4) achieving a blood flow of 200 to 300 mL/min; and (5) they were providing crucial medical records and doing routine follow-up. The identical dialysate (dialysate sodium 140 mmol/L, dialysate potassium two mmol/L, dialysate calcium 1.5 mmol/L, and dialysate temperature 37 °C) was administered to each participant. The exclusion criteria were the difficulty accessing medical information, modifications to the dialysis modality, and the occurrence of an illness or trauma unrelated to hemodialysis within a month. A flow chart of the case selection and research procedure is shown in Fig. 1.

Ethics and informed consent

The Declaration of Helsinki’s tenets were followed throughout the study. The Ethics Committee of the First People’s Hospital Center of Nantong granted informed consent to all participants, and this consent was authorized (ethical approval number 2024KT435).

Data collection and variable definition

34 factors, comprising fundamental characteristics, dialysis-related data, and blood laboratory test data, were gathered from the hemodialysis management system after the data ratio was randomly split into training and validation sets by a 7:3 ratio. 34 factors, including essential variables like gender, age, height, weight, smoking history, and coupled hypertension or diabetes, were gathered from the hemodialysis management system after the entire dataset was randomly split into training and validation sets in a 7:3 ratio. Blood flow, hemodialysis duration, dialysis duration, blood volume, ultrafiltration volume, predialysis heart rate, predialysis systolic blood pressure, predialysis diastolic blood pressure, and dialysis adequacy measurements (Kt/V urea, URR) were among the data about dialysis. Neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, hemoglobin, platelet count, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, albumin, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, bile acids, lactate dehydrogenase, glutamyl transpeptidase, uric acid, β2 microglobulin, prealbumin, and prealbumin were among the blood laboratory tests. Moderate vomiting served as the study’s primary outcome assessment. Using the Korttila scale, vomiting severity was classified as follows: no vomiting, mild vomiting (less than three episodes of vomiting with or without gastric emptying), moderate vomiting (three to five episodes of vomiting with or without gastric emptying), and severe vomiting (more than five episodes of vomiting with or without gastric emptying)16.

Identify the best predictors

Feature selection was performed in the training cohort. We employed a rigorous feature selection approach to incorporate the predictors most relevant to model construction to ensure that only the most appropriate and robust variables were included in the prediction model. LASSO regression can obtain optimal constrained models by compressing feature coefficients through penalty functions; this approach has been effectively used to avoid overfitting and collinearity in classical analytical methods based on significant differences and enhance models’ generalization ability. Boruta’s algorithm is a wrapper algorithm using random forest classification. This practice can iteratively remove those features that are less relevant to random probing, thus aiming to retain variables associated with the response variable function. In addition, these two algorithms are particularly suitable for datasets with small sample sizes but large numbers of variables. Therefore, we further used the Boruta algorithm17 after using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) algorithm18 to obtain the final significant predictors.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test or Student’s t-test, and the results were displayed as the median and interquartile range or mean ± SD. The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was an alternate method for evaluating categorical data shown as numbers (%). To find risk factors for vomiting, we first screened the factors using univariate logistic regression analysis of the training group. Then, we used LASSO regression to reduce the dimension of high-dimensional data and find the best variables and predictive characteristics for vomiting (25). Their calibration (calibration graph) and discriminant capacity (C-statistic) are evaluated to validate nomograms. C-statistic values above 0.75 are generally seen as a sign of excellent discriminant ability. Lastly, we used decision curve analysis (DCA) and clinical impact curves (CIC) to gauge how applicable nomograms are in clinical practice. A significance level of p < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

Clinical features

Between January 1, 2023, and October 31, 2024, 281 patients who received hemodialysis at the Nephrology Clinic of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University provided us with data. 196 patients (67.26%) did not vomit during dialysis, while 92 patients (32.74%) did. The patients’ demographic details are included in Table 1.

Risk factors associated with vomiting

Further univariate logistic regression analysis found Fifteen factors to be statistically significant (P < 0.05). The findings of the univariate analysis are summarized in Table 2. We used a 10-fold cross-validation strategy using pi incidence as the dependent variable and Lambda to internally validate the 15 significant factors for our subsequent univariate analysis because we had many covariates. Min was chosen as the filter variable for λ. The Lasso approach uses seven variable coefficients that change with penalty coefficients to filter variables, as shown in Fig. 2A numerically. The coefficient of the initial integration component is compressed and eliminated from the model when the coefficient is 0. Every row represents a different variable. The target variables were identified using the area under the ROC curve (ACU) with 10-fold cross-validation, as seen in Fig. 2B. Finally, seven factors were chosen: sex, height, diabetes, heart rate, spKt.V, lactate dehydrogenase, and lymphocytes (Table 3). We subsequently performed the Boruta feature selection algorithm on the optimum parameters. We ultimately chose six variables, including gender, height, heart rate, spKt.V, lymphocytes, and lactate dehydrogenase, to differentiate between vomiting and non-vomiting patients (Fig. 2C). After that, the six variables were given values and subjected to logistic multivariate regression analysis. Numerous collinearity diagnostics were used for the logistic regression analysis data to examine the collinearity between variables. The findings demonstrated no collinearity and that each index’s variance inflation factor (VIF) was less than 5. Six components were ultimately incorporated into the regression model after regression analysis was conducted using the complete inclusion approach.

While LASSO is used for significant variable selection, the Boruta method is employed for feature selection. (A) LASSO coefficient profiles of the clinical characteristics. (B) The optimal penalization coefficient lambda was obtained using tenfold cross-validation in LASSO. The graphic shows the lambda value of the most minor mean square error. The most minor absolute shrinkage and selection operator is known as LASSO. (C) The function selected by Boruta. The blue boxplots correspond to the minimum, mean and maximum Z-scores of the shaded attributes. Z-scores clearly distinguish between important and non-important attributes. Red and green represent attributes that Boruta chooses to reject and confirm, respectively.

Modal chart model for estimating the risk of vomiting

The enrolled patients were split into training and test groups in a 7:3 ratio using a randomized stratified grouping technique (Supplementary Data). We developed tailored nomogram estimates to predict the likelihood that patients will vomit during hemodialysis based on the risk variables chosen using Lasso regression and binary logistic regression (Fig. 3). On a scale of 0 to 100, each element was given a score on a modal plot representing its regression coefficient concerning the need for vomiting. The cumulative score, determined by summing the scores for each category, assesses a person’s risk of vomiting. A vertical line in this computation represents each factor axis that crosses the nomogram’s point axis. For explanation, the final total score can then be compared to the total score table.

Clinical nomograms based on multiple logistic regression analysis and Boruta’s method for feature selection were used to predict the likelihood of vomiting in HD patients. A line connecting the corresponding value to a “dot line” was constructed for each indication to assign points. We may determine the patient’s risk of vomiting by calculating the probability of identical “totals” and utilizing the individual score totals of the six measures that make up the nomogram.

Validation of nomogram models

For the training cohort model (Fig. 4A), the AUC was 0.847 (95% CI: 0.791–0.9027), and for the testing cohort model (Fig. 4B), it was 0.847 (0.7603–0.9333). Both the training and testing cohorts show that the model is calibrated correctly. The model was well adjusted based on the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for the validation cohort (χ2 = 4.4677, P = 0.8127) and the training cohort (χ2 = 3.9703, P = 0.8598). According to the calibration analysis, the model was calibrated using 500 Bootstrap internal sampling. Figure 5A shows the training set’s Brier score of 0.150 with a p-value of 0.957 (> 0.05), whereas Fig. 5B shows the validation set’s Brier score of 0.146 with a p-value of 0.645 (> 0.05). The calibration curve demonstrated a robust relationship between the actual likelihood of occurrence and the projected probability.

Analysis of clinical practicability and rationality of prediction model

We used the incidence of vomiting during dialysis as a state variable and the projected likelihood of the calibration plot as a test variable to evaluate the nomogram’s clinical value. As seen in Fig. 6, we created a clinical decision curve (DCA) for the nomogram model. The threshold probability is shown on the X-axis, and the net benefit is shown on the Y-axis. A solid gray line means all the patients threw up, whereas a narrow, solid black line means none did. The decision curve indicates that the model is clinically useful throughout a relatively wide threshold probability range. In contrast, the red curve shows the advantage for patients utilizing the predictive model for this study. Furthermore, as demonstrated by the clinical effect curves (Fig. 7A, B), this prediction model performs well in clinical applications since the two curves nearly coincide when used to stratify a population of 1000 individuals.

Clinical impact curve. During training (A) and validation (B), the clinical impact curve of the model was observed. The red line indicates the number of individuals the model considers high risk based on different probability factors. The blue line shows how many individuals the model considers to be at high risk have an outcome event that falls below specific probability requirements.

To provide a more thorough assessment, we contrasted the ROC curves of the predicted nomograms with those of models that only used one predictor. When gender, height, heart rate, spKt.V, lymphocytes, and lactate dehydrogenase were used alone, the nomogram area under the curve was more significant than the model’s, indicating that vomiting was consistently lower for individual predictors than for the prediction model; This suggests that the model performed robustly. Figure 8 illustrates the model’s plausibility.

Discussion

Around the world, more than a million dialysis patients are still alive. The lives of hundreds of thousands of patients with end-stage renal illness have been prolonged by the widespread use of dialysis19. However, hemodialysis does not eliminate all of the difficulties brought on by renal failure, even though it is essential in saving the patient’s life. Therefore, Hemodialysis patients have several problems20,21. More than 25% of hemodialysis patients have common side symptoms, such as hypotension, muscular cramps, nausea and vomiting, headache, chest discomfort, back pain, fever, and shivering22. Predictive models are gaining more attention in several clinical domains, including sepsis, Kawasaki disease, and malignant tumors. Additionally, there is a growing body of pertinent research in these domains23,24,25,26. Predictive models for the onset of vomiting during hemodialysis are still lacking, nevertheless. Therefore, to support clinical decision-making and offer individualized treatment plans, we set out to create a prediction model for the onset of post-dialysis vomiting.

34 variables were included in our retrospective analysis of the clinical and laboratory data of 281 hemodialysis patients, including easily accessible laboratory, anthropological, and dialysis-related data. Gender, height, heart rate, spKt.V, lymphocytes, and lactate dehydrogenase were found to be independent predictors for vomiting in dialysis patients using several statistical techniques. We created a straightforward and precise nomogram, verified it internally, and demonstrated the model’s clinically solid applicability and effectiveness. They were vomiting to offer individualized treatment plans and to support clinical decision-making.

In our group, vomiting occurred 32.74% of the time, which aligns with earlier results9. Hemodialysis-induced nausea and vomiting have several etiologies. A fast decline in blood pressure or urea causes this problem in many dialysis patients9. The primary causes of nausea and vomiting are also thought to be a variety of factors, including the impact of ESRD and its treatment on the digestive system, the food of the patient, medication schedules, and developmental abnormalities. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal mucosal edema (with early satiety) are all linked to fluid excess7. Other early signs of disequilibrium syndrome include nausea and vomiting. Dialyzer responses of type A and type B both contribute to these symptoms. Dialysis patients may have worsening nausea and vomiting due to elevated dialysate sodium and calcium levels9. Hemodialysis patients may experience nausea if they eat on the dialysis machine or within an hour of beginning dialysis9. When Shahdadi et al. compared nausea and vomiting during hemodialysis in semi-sitting and supine postures, the majority of the participants were female9. Our prediction model also revealed a greater heart rate, spot, and a shorter height. Lower lymphocyte lactate dehydrogenase levels and V values may put patients at greater risk of vomiting. According to Feng et al., lymphocytes strongly predict postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) following total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and are an independent risk factor for this occurrence27. According to another study, heart rate is a significant predictor of post-spinal anesthesia PONV and an expected incidence of the condition28. According to research by Johansson et al., individuals who were shorter, lighter, and had a lower BMI were more likely to get PONV29. The hemodialysis population had higher lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, according to Fang et al. LDH was highly correlated with QTc prolongation, one of the frequent causes of patients’ sudden cardiac death30. Kt/V and URR are widely acknowledged as the most crucial metrics for measuring and tracking dialysis effectiveness31,32. Dialysis involves the removal of large volumes of fluid from the body. The circulatory system tightens the muscle arteries to compensate for the body’s loss of these fluids, which can cause vomiting and stomach pains. However, no studies have shown a direct association between urea levels, Kt/V, URR values, and vomiting. However, Kt/V is an essential measure of dialysis adequacy, where K represents urea clearance from the dialyzer, t represents dialysis time, and V represents urea volume of distribution. Higher values of Kt/V indicate adequate dialysis. Inadequate dialysis may lead to the accumulation of toxins in the body, causing symptoms such as nausea and vomiting. Urea is the end product of protein metabolism, and its level can reflect patients’ nutritional status and dialysis effect. High urea levels are usually associated with excessive protein intake or inadequate dialysis. High urea levels may cause uremic symptoms, including nausea and vomiting. URR measures urea removal efficiency during dialysis and is calculated as (pre-dialysis urea – post-dialysis urea)/pre-dialysis urea. Higher URR values indicate better dialysis. Low URR values may indicate poor dialysis results, causing urea to accumulate and increasing the risk of vomiting.

Using gender, height, heart rate, spKt.V, lymphocytes, and lactate dehydrogenase as predictors, we created a nomogram for the first time in this study’s development of a prediction model for vomiting in hemodialysis patients. The nomograms and the validation set’s risk prediction abilities were 0.847. The three primary benefits of this study are as follows: first, prediction models are built using straightforward and objective clinical data; second, the variables used to create the models are easily accessible, significantly enhancing the model’s universality and making it easier to apply in clinical practice. Finally, our nomograms demonstrated significant calibration, stability, and distinction.

Several restrictions exist on the current investigation. The small sample size of this single-center cross-sectional study raises the possibility of selection bias. We will further conduct a multicenter study to include patients from different regions and medical institutions to improve the diversity and representativeness of the sample. Furthermore, we only validated nomogram models internally; external validation was also necessary for further research. Large, multicenter, prospective studies may be conducted to find other risk factors for vomiting issues in HD patients. This would allow for the early implementation of appropriate strategies to prevent vomiting during dialysis, which would prevent dialysis from continuing and alleviate patient suffering. In addition, we will further mine the medical records of patients and collect more perfect variable data to improve the comprehensiveness and accuracy of prediction models; secondly, methods to improve existing models, including the introduction of machine learning algorithms (such as random forests, support vector machines, or deep learning) to deal with nonlinear relationships and complex interactions, while optimizing model performance in combination with feature selection techniques.

Conclusion

We established a prediction model for vomiting risk in HD patients, which provides a valuable reference for identifying and preventing vomiting risk.

Data availability

Datasets of the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Pecoits-Filho, R. et al. Capturing and monitoring global differences in untreated and treated end-stage kidney disease, kidney replacement therapy modality, and outcomes. Kidney Int. Suppl. 10, e3–e9 (2011).

Bello, A. K. et al. Assessment of global kidney health care status. JAMA 317, 1864–1881 (2017).

Bello, A. K. et al. Status of care for end stage kidney disease in countries and regions worldwide: International cross sectional survey. BMJ 367, l5873 (2019).

Htay, H. et al. Hemodialysis use and practice patterns: an international survey study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 77, 326–335 (2021).

Rocha, A., Sousa, C., Teles, P., Coelho, A. & Xavier, E. Effect of Dialysis day on intradialytic hypotension risk. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 41, 168–174 (2016).

Abdel-Kader, K., Unruh, M. L. & Weisbord, S. D. Symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in chronic and end-stage kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 4, 1057–1064 (2009).

Chong, V. H. & Tan, J. Prevalence of Gastrointestinal and psychosomatic symptoms among Asian patients undergoing regular Hemodialysis. Nephrology (Carlton) 18, 97–103 (2013).

Patel, N., Dalal, P. & Panesar, M. Dialysis disequilibrium syndrome: a narrative review. Semin. Dial. 21, 493–498 (2008).

Asgari, M. R. et al. Incidence and severity of nausea and vomiting in a group of maintenance Hemodialysis patients. J. Ren. Inj. Prev. 6, 49–55 (2017).

Barth, C. et al. Characteristics of hypotension-prone haemodialysis patients: is there a critical relative blood volume? Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 18, 1353–1360 (2003).

Badet, T., Fouché, S., Hartmann, F. E., Zala, M. & Croll, D. Machine-learning predicts genomic determinants of meiosis-driven structural variation in a eukaryotic pathogen. Nat. Commun. 12, 3551 (2021).

Zhou, H., Xin, Y. & Li, S. A diabetes prediction model based on Boruta feature selection and ensemble learning. BMC Bioinform. 24, 224 (2023).

Li, M. et al. Development and assessment of novel machine learning models to predict medication non-adherence risks in type 2 diabetics. Front. Public. Health 10, 1000622 (2022).

Meng, Z. et al. Development and validation of a predictive model for severe COVID-19: A case-control study in China. Front. Med. 8, 663145 (2021).

Ding, X., Qin, J., Huang, F., Feng, F. & Luo, L. The combination of machine learning and untargeted metabolomics identifies the lipid metabolism-related gene CH25H as a potential biomarker in asthma. Inflamm. Res. 72, 1099–1119 (2023).

Korttila, K. The study of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br. J. Anaesth. 69 (7 Suppl 1), 20S–23S (1992).

Speiser, J. L., Miller, M. E., Tooze, J. & Ip, E. A comparison of random forest variable selection methods for classification prediction modeling. Expert Syst. Appl. 134, 93–101 (2019).

Vasquez, M. M. et al. Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator type methods for the identification of serum biomarkers of overweight and obesity: simulation and application. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 16, 154 (2016).

Mahdavi-Mazdeh, M. et al. Renal replacement therapy in Iran. Urol. J. 4, 66–70 (2007).

Yamada, S., Tsuruya, K., Kitazono, T. & Nakano, T. Emerging cross-talks between chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD) and malnutrition-inflammation complex syndrome (MICS) in patients receiving Dialysis. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 26, 613–629 (2022).

Ahmad, M. M. & Al Nazly, E. K. Hemodialysis: stressors and coping strategies. Psychol. Health Med. 20, 477–487 (2015).

Marengo, M. et al. Role of the CD40-CD40 ligand pathway in cardiovascular events, neurological alterations, and other clinical complications of chronic Hemodialysis patients: protective role of adsorptive membranes. Blood Purif. 52, 27–42 (2023).

Ren, C. et al. Development and external validation of a dynamic nomogram to predict the survival for adenosquamous carcinoma of the pancreas. Front. Oncol. 12, 927107 (2022).

Zeng, W. et al. Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting postoperative distant metastasis in patients with cervical cancer. Med. Sci. Monit. 28, 1 (2022).

Lu, B. et al. Development of a nomogram for predicting mortality risk in sepsis patients during hospitalization: A retrospective study. IDR 16, 2311–2320 (2023).

Yang, S., Song, R., Zhang, J., Li, X. & Li, C. Predictive tool for intravenous Immunoglobulin resistance of Kawasaki disease in Beijing. Arch. Dis. Child. 104, 262–267 (2019).

Feng, D. et al. Effectiveness of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios in predicting the incidence of nausea and vomiting after total knee arthroplasty in patients with hemophilia A. Front. Surg. 10, 1120930 (2023).

Ju, J-W., Kwon, J., Yoo, S. & Lee, H-J. Retrospective analysis of the incidence and predictors of postoperative nausea and vomiting after orthopedic surgery under spinal anesthesia. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 76, 99–106 (2023).

Johansson, E., Hultin, M., Myrberg, T. & Walldén, J. Early post-operative nausea and vomiting: A retrospective observational study of 2030 patients. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 65, 1229–1239 (2021).

Fang, X-X. et al. Correlation between lactate dehydrogenase and QTc interval prolongation in maintenance Hemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional study. Ann. Palliat. Med. 11, 3444–3454 (2022).

Tattersall, J. et al. EBPG guideline on Dialysis strategies. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 22 (Suppl 2), 5–21 (2007).

National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for Hemodialysis adequacy: 2015 UPDATE. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 66, 884–930 (2015).

Funding

The present study was supported by the Nantong Science and Technology Bureau (JCZ21099, JC22022021), Jiangsu Health Committee Project (Z2022014), Nantong Science and Technology Bureau (MS22022085), Clinical special research fund of Nantong University (2024LQ019), Nantong Health Commission Directive Project (MS2024036), Nantong Health Commission Scientific Research Project (QA2021015), and Nantong Health Committee Project (QA2021015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JJC wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CS, HYX, BYY, BZ, and JJC collected and analyzed the data. LLS, XXF supervised the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The research involving human subjects was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committee of the First People’s Hospital of Nantong, in strict adherence to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Shen, C., Xue, H. et al. Development of an early prediction model for vomiting during hemodialysis using LASSO regression and Boruta feature selection. Sci Rep 15, 10434 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95287-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95287-1