Abstract

Phase coherence and amplitude correlations across brain regions are two main mechanisms of connectivity that govern brain dynamics at multiple scales. However, despite the increasing evidence that associates these mechanisms with brain functions and cognitive processes, the relationship between these different coupling modes is not well understood. Here, we study the causal relation between both types of functional coupling across multiple cortical areas. While most of the studies adopt a definition based on pairs of electrodes or regions of interest, we here employ a multichannel approach that provides us with a time-resolved definition of phase and amplitude coupling parameters. Using data recorded with a multichannel µECoG array from the ferret brain, we found that the transmission of information between both modes can be unidirectional or bidirectional, depending on the frequency band of the underlying signal. These results were reproduced in magnetoencephalography (MEG) data recorded during resting from the human brain. We show that this transmission of information occurs in a model of coupled oscillators and may represent a generic feature of a dynamical system. Together, our findings open the possibility of a general mechanism that may govern multi-scale interactions in brain dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Functional connectivity (FC) is a measure of the statistical dependencies between the time series recorded from two neuronal populations or brain regions. Evidence supports the idea that FC reflects the communication at different scales in the brain and is highly relevant for brain dynamics. For electrophysiological recordings, a useful approach is to decompose the signals by their phase and amplitude. These representations have revealed the coexistence of two main modes or mechanisms of communication between brain regions. The first one corresponds to a fixed relation between the phases of two brain sources and is measured by coherence1,2. In the second one, the amplitude or envelope of the signals are correlated, suggesting coordinated excitability fluctuations between areas2,3,4. Both connectivity modes have been associated with a broad variety of brain disorders5 and cognitive processes6,7 and for many years the studies of FC have been focused on one or the other coupling mode. Whether both types of connectivity are equivalent or perhaps redundant has been addressed recently in studies showing that these coupling modes can differentiate strongly, especially during presence of stimulation7,8. Furthermore, patterns of both coupling modes differ across cortical areas and frequency bands. Although linear measures of phase-phase and amplitude-amplitude correlations may be mathematically equivalent for Gaussian-distributed signals9, neural signal distributions may be disrupted by external stimuli10, motor execution11, or changes in brain state12. Consequently, Gaussianity cannot be taken for granted, even during rest13. Thus, while there are two distinct coupling mechanisms, the nature of their relationship remains unclear. One possibility is that they are two representations of a more general mechanism, in which case their relationship would likely be limited to a statistical dependency. The other possibility, which presents a more dynamic perspective, is that one of the mechanisms drives the other.

Here, we explore the possibility that phase- and amplitude-coupling are related through a causal interaction. One difficulty that we faced when addressing this question is that the statistical dependencies that operationalize FC are defined during a certain time window, which ideally is determined by the frequency band of the underlying neural oscillations. This time window should be sufficiently long to allow for a significance testing. However, if the time window is much longer than the causal interaction there is a high risk that any causal effects may be blurred. To avoid this issue, we adopted an alternative strategy that consists of defining a parameter of similarity across signals in a multichannel manner. This approach allows us to obtain time-series that reflect how consistent phase and amplitude are across channels. These two time-series, that we called phase-consistency (PC) and amplitude consistency (AC), are defined for each time-sample, on which causality analysis can be applied without restrictions or further assumptions. We applied this approach to data recorded from the ferret brain using custom-made µECoG arrays with electrodes covering a large part of the left cerebral hemisphere. Furthermore, we tested whether the results can be confirmed in MEG recordings of resting activity from the human brain. Finally, we explored in a computational neural-mass-model whether such causality effects can be generated from a common neural mechanism.

Results

Time-resolved spatial phase and envelope consistencies

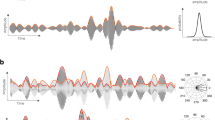

We hypothesized that if a causal interaction between phase and amplitude connectivity modes exists, then this should be in the time scales defined by the signal’s frequency. In this case, time scales of the order of one oscillatory cycle are clearly too short for the standard measures of connectivity14. To measure a causal relation with fine temporal resolution we defined magnitudes that describe the similarity in phase and amplitude across multiple channels at each time point t’. For this purpose, we replaced the standard pairwise window-based approach of connectivity1,3,4,15 with a multichannel measure of similarity across channels for each time t’. For phase, similarity is measured by the phase consistency (PC), defined in Eq. (3) (see Methods), which is a function of the instantaneous phases \(\:{\varphi\:}_{k}\left(t\right)\) (with \(\:k=\{1,\dots\:,\:9\}\:\), the channel index) and N, the total number of channels. Analogously, for the envelope we used the inverse of the coefficient of variation, defined in Eq. (4) (see Methods), where \(\:\mu\left(t\right)\) is the envelope’s mean and \(\:\sigma \left(t\right)\) is the standard deviation. Figure 1B displays example recording traces of 9 channels located over the visual cortex and filtered at 1–2 Hz (top) and their corresponding PC and AC time series (middle and bottom rows, respectively).

Quantification of PC and AC in ferret LFP data. (A) Representation of our custom-made µECoG array on the left hemisphere of the ferret cortex. Colors indicate the three functional systems: visual (blue), auditory (green), parietal (yellow). (B) Top: Traces of LFP signals (2–4 Hz) of 9 channels located over the visual cortex. Middle: Phase consistency (PC) associated to the above signals. Bottom: associated amplitude’s consistency (AC). (C) The number of electrodes in PC and AC was chosen based on the similarity (correlation r) between the distributions with N and N + 1 electrodes. Between 9 and 10 electrodes the similarity was significantly strong. (D) Spectral characteristics of PC (orange) and AC (blue) for different frequency bands of the underlying oscillatory signals.

Clearly, time series, as defined in Eqs. (3) and (4), are sensitive to the size N. In our study, the selection of N is a trade-off between stability in the probability distributions of PC and AC and the number of channels. One of our goals was to perform the current analysis of the ferret LFP data for two distributions of channels located either within the same functional cortical system or in different systems. Therefore, we selected the smallest number of channels N for which the difference of the probability distribution was small compared with the distribution obtained for a N + 1 population. In this manner, we could establish the minimum number of channels required for the within-system condition. Figure 1C shows that the addition of one channel in the population becomes less relevant as the population increases, and that the correlation between N = 9 and N = 10 is highly significant (r > 0.97). Hence, further analyses on the ferret data were performed taking N = 9 electrodes.

Finally, we asked whether PC and AC conserve the spectral characteristics of the preprocessed signal. We found for all frequency bands that in general PC and AC spectral distributions were at lower frequencies than the frequency band from which they originated (Fig. 1D), implying that PC and AC act as low-pass filters. Any component in PC or AC with higher frequency than the LFP signal would suggest the presence of artifactual events.

Joint probability distribution of PC and AC

To characterize the statistical dependencies between both quantities we calculated the joint probability distribution \(\:p(PC;AC)\) across frequency bands for the ferret LFP data. First, we considered electrodes placed over visual areas according to the anatomical maps16 and Fig. 1A) and divided the corresponding PC and AC time series in intervals of 10 s. The resulting probability distribution across intervals and animals is shown on the top row of Fig. 2. The distributions show a clear relationship between measures that is highlighted by the cyan lines, which describe the path along which AC is maximal given a certain PC. This relation was stronger at low frequencies; however, it was maintained up to 128 Hz. As a control we computed the distributions when intervals were shuffled (Fig. 2, bottom row). Under this condition the time relation within each measure was conserved for each measure, but the time relation between intervals was eliminated. In other words, the joint distribution of AC and PC was the product of marginal distributions of AC and PC, demonstrating their statistical independence. This result supports the hypothesis of a relationship between both measures. Note that this relationship does not imply causality yet, but describes a mere statistical dependency between both measures.

Joint probability distribution of the time series PC and AC in ferret LFP data. To build these distributions we took 100 time-windows of 30 s each for all animals. Cyan lines describe the highest probability of AC given a PC. The distributions in the top row suggest a relation between PC and AC that extends to all frequency bands. Bottom row shows the distribution after shuffling the time-windows of both time-series. Note that the cyan line is almost flat, showing the absence of a relation.

Causal relation between phase- and amplitude consistencies

We hypothesized that the observed correlation might be more than a chance statistical dependency of multichannel phase and amplitudes and, rather, indicate a causal interaction between both coupling modes. To test this hypothesis, we measured causality between PC and AC using transfer entropy (TE), a model-free method that been used previously in neuroscience to estimate connectivity17,18. Again, we extended our analysis across frequency bands, as defined in the previous section. To rule out effects of the electrode selection, we calculated the causality considering electrodes placed over visual areas, over auditory areas and globally distributed across all three functional systems. We contrasted both directions in the causality, i.e., assuming that PC is the leader and AC is the follower (\(PC\to\:AC\)) and the inverse condition (\(AC\to\:PC\)). The dots in the distributions (Fig. 3) represent the TE during intervals of 30 s. Intervals were non-overlapping and randomly selected. We evaluated statistical significance against surrogate data for each interval individually18,19,20. The results show a consistent asymmetry in causality dominated by the flow of information \(\:AC\to\:PC.\) This result was statistically significant in frequency bands below 8 Hz (p < 10−4, N = 343). For higher frequencies (8 to 128 Hz) the flow of information in both directions was not significantly different from the random condition at all.

Causal relations \(\:AC\to\:PC\) and \(\:PC\to\:AC\). The causal relation was measured by TE on interval basis (each dot represents an interval of 30 s). Horizontal bars show the median TE. (A) TE for different frequency bands in ferret LFP data. Top and middle rows represent conditions where we considered electrodes only over the visual and auditory cortex, respectively. Bottom row represents the sparse condition where we took electrodes from areas regardless of the functional system. We observe a prominent leader role of amplitude coupling (cyan color) with respect to the opposite condition, in particular at low frequency bands (< 8 Hz). (B) \(\:AC\to\:PC\) side-by-side comparison of between the three functional distributions for the ferret data. (C) Transfer entropy for \(\:AC\to\:PC\) and \(\:PC\to\:AC\) in human MEG during resting state. AC and PC were obtained from 9 sensors at the occipital region of the left hemisphere.

In the same analysis we asked whether the causality relations are specific to the electrode distribution or the cortical system. Similar patterns of distribution were observed if electrodes were located only in visual areas, only in auditory areas and globally distributed (Fig. 3B). Altogether, our results show a similar causal relation between global network properties based on phase and amplitude coupling modes, suggesting that the mechanisms involved are inherent to the dynamics of the neural networks and not specific to a particular functional brain system.

The above observations might be related to the recording approach, the spatial scale of the signals and the species under consideration. We therefore explored the validity of our results in magnetoencephalography (MEG) data recorded in humans during the resting state (Fig. 3C). We selected 9 sensors located above the occipital cortex of 10 healthy subjects. The selection of the frequencies of the filters were defined as for the ferret LFP data and the duration of the interval for TE computation (dots in Fig. 3C) was also 30 s. Interestingly, despite the strong differences in nature and spatial scale of the signals, the asymmetry of TE for AC to PC vs. PC to AC observed in the MEG recordings resembled closely the results obtained for the ferret data. However, this asymmetry extended up to 16 Hz, in contrast to 8 Hz of the ECoG signal. Thus, our results may reveal a fundamental mechanism that is independent of the spatial scale, the recording approach or the species.

Causal relation is brain-state independent

As we showed in a previous study12, the short duration of the sleep-wake cycle in the ferret al.lows the recording of several brain-states within a single recording session. We asked whether the different types of causality observed above were associated with functional states of the brain. For this we defined the asymmetry ratio \(\:AR=\frac{TE\left(AP\right)}{TE\left(PA\right)}\) for all intervals by which at least one of the causalities was significant. Thus, a ratio AR > 1 means that an alignment in amplitude across channels leads to an alignment in the respective phases, whereas AR < 1 means the opposite direction. A value AR close to 1 means bidirectionality. In addition, we classified the recordings in three main states using their spectral properties, as detailed in Methods. In general, statistical analysis showed no significant evidence that directionality in the causality might be related to the putative brain state (Kruskal-Wallis H test; p > 0.1). This result extended to all frequency bands and distributions of electrodes in the cortex.

Information transfer delay

Once demonstrated that the spatial consistency in amplitude may influence the spatial consistency in phase, we proceeded to determine the timescale for this interaction. In its original notation17, transfer entropy between two random processes is defined as \(\:TE\left(X\to\:Y\right)=I\left({Y}_{t+1};{X}_{t}|{Y}_{t}\right)\), where t = 1 is the delay between leader and follower. The true interaction delay between variables X and Y is equivalent to the reduction of uncertainty in Y when considering the past values of both Y and X, compared to considering the past values of Y alone21

We let the parameter \(\:k\) vary between 1ms and 5 s and determined the interaction delay \(\:\delta\:\) between both time series as

This analysis was separately done for the 3 frequency bands between 1 and 8 Hz (Fig. 4). First, we found similar curves that describe the transfer entropy as function of the delay, with maxima at 208 ms (1–2 Hz), 180 ms (2–4 Hz) and 176 ms (4–8 Hz). In all three bands, the delays correspond to half to one cycle of oscillation, suggesting a mechanism that occurs within a single oscillation cycle and sets an upper limit in the time-scale of the interaction.

Computational simulation

We explored whether the characteristics of multichannel coupling and information transfer, as shown above, are exclusively associated to biological processes or rather may reflect a more fundamental property of a dynamical system. To address this question, we used a model based on a non-biological approach. Our rationale here was, if a non-biological system is not able to reproduce characteristics such as the joint distribution of PC or AC, or the transfer of information, there is the possibility that the observed phenomena have their roots in the complexity of a biological network. On the other hand, if such characteristics were reproduced by a non-biological model, then the transfer of information might represent a general network property.

We used a simple model which consisted of an array of 9 masses coupled by Hooke’s law. We allowed interactions between all couples of masses, mimicking cortical connectivity in a highly simplified manner. The model does not explicitly include parameters such as synaptic delays or excitation and inhibition. However, one could interpret the amplitude of the oscillation of each mass as representing a local field potential. Example traces of simulated signals and the corresponding PC and AC are shown in Fig. 5A. Our model predicted a joint probability distribution of PC and AC (Fig. 5B) that resembled the experimental data (Fig. 2) with maximal probability at PCmax = 0.96 and ACmax = 3.7. Interestingly, this simple model not only reproduced the causal effect but also the direction of the causality (Fig. 5C), assigning the AC the role of the leader and PC the role of the follower as in the low frequency bands in neurophysiological data.

Computational model. For the simulation we considered a set of 9 coupled oscillators allowing pairwise all-to-all interaction. (A) Traces of PC and AC obtained for simulated traces of coupled oscillators. Note the similarity with the experimental data (Fig. 1B) (B) Joint probability distribution. The similarity with the experimental result is remarkable. (C) Contrast of TE between both directionalities. Our simulation reproduced the leading role of AC to PC.

Analysis of surrogate data

The fact that the time-delay between PC and AC has a relation to the oscillation cycle could be interpreted as an indication that the observed relationships reflect the type of signal, rather than a physical property of the system. To rule out this possibility, we contrasted the analysis of original data with surrogate data. Surrogate time series were generated using the Iterative Amplitude Adjusted Fourier Transform (IAAFT) algorithm22. This method allows the generation of surrogate time series preserving both the amplitude distribution of the original signal and its autocorrelation function, while introducing phase-shifts compared to the respective original data (Fig. 6A). We tested the model for the 1–2 Hz condition in two subjects, using the signals from the same 9 electrodes over the visual cortex as targets. Figures 6A to C show a segment, power spectrum, and autocorrelation function of an original signal (black) and a surrogate (red) time series, which illustrate their statistical equivalence. The resultant PC and AC, and their joint probability distributions, are displayed in Figs. 6D and E, respectively. Note the contrast with the joint probability distribution in original data (Fig. 2, panel top-left), which shows a larger correlation in phase and amplitudes across channels. For each original interval, extracted from two animals, we calculated 100 surrogates and the mean TEsurr and divided it by its original TEorig. The fact that the distribution of the values for the quotient TEsurr/TEorig was consistently lower than 1 (Fig. 6F) demonstrates that the result is not driven by the characteristics of the signals, but describes a property of the system, validating our results obtained on the original data.

Transfer entropy in surrogate data. (A) 15-seconds segment of an original LFP signal (black) and its surrogate (red), both band-pass filtered (4–8 Hz). (B) Power spectral distribution of the original signal (black) and a surrogate time series (red dashed). (C) Autocorrelation functions of the original (black) and surrogate (red-dashed) signals. The green line represents the cross-correlation between the two time series. (D) Segment of corresponding surrogate PC and AC. (E) Joint probability distribution of PC and AC. (F) Normalized TE. For each of the original 9 channel conditions, we generated 100 surrogate time series, filtered them, and calculated the corresponding TE(AC→PC) and TE(PC→AC). The figure shows the distribution of surrogate TE in which each dot represents the mean value (across the 100 repetitions) normalized by the original TE AP-> PC. The asterisks (***) indicate statistical significance p < < 0.001.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that the two major modes of FC that are known to exist in cortical networks, namely, phase- and amplitude-coupling of neural signals2,6, interact with each other in a causal manner in ongoing brain activity. Our study was carried out in awake freely moving ferrets using a custom-made µECoG array7,12 that allows distributed recordings over large cortical networks with small-sized electrodes that capture rather localized activity, presumably of only few cortical columns23. In addition, we analyzed the relation between phase- and amplitude-coupling in human resting state data recorded with whole-head MEG4,8.

Modes of phase and amplitude interaction have been studied for many years mostly in the context of cross-frequency coupling. In its most common version, the modulation of the amplitude at high frequencies by the phase of low frequency components is quantified24. This type of interaction, however, describes an instantaneous cross-frequency correlation between different features of signals from the same recording site.

Our study aimed to find a causal relation between different intrinsic coupling modes2 occurring across distributed areas in the cortex. We have introduced gross measures of spatial similarity in phase and amplitude across multiple channels to characterize phase and amplitude’s similarity at each time point t’, under the assumption that strong functional coupling results in high similarity of signals across recording sites. First, the interpretation of the resultant time series PC and AC must be taken carefully. Contrary to standard measures of connectivity, where values of 1 and 0 mean strong and no-coupling, respectively, PC may have any value in between even if the signals are perfectly coupled. For instance, if the signals have different phase, but the difference between them remains constant, then PC would be a number between 0 and 1 that remains constant over time. Similarly, a low AC does not necessarily mean low connectivity. Therefore, we assume that in both coupling modes the mean strength relates inversely with the variability of PC and AC across time, rather than their instantaneous value. In fact, we observed unexpected transient periods of desynchronization represented by sudden decreases of PC. This behavior exhibits similarities to the metastable oscillatory modes (MOMs) recently reported in Cabral et al.25, which arise at sub-gamma frequencies. These modes are influenced by global parameters such as mean oscillation frequency and mean coupling, rather than the connectomic structure itself.

By means of transfer entropy we have observed a causal relation between AC and PC. This interaction occurs predominantly at low frequencies (1–8 Hz), with amplitude coupling assuming the leading role and phase coupling that of the follower. This result suggests that amplitude coupling, which likely reflects coordinated excitability fluctuations, can have a causal impact on more precise phase coupling in neural networks2,6. The leading role of amplitude at low frequencies contrasts with local cross-frequency phase-amplitude coupling, in which the phase at low-frequencies modulates the amplitude of high-frequency oscillations24.

One of the reasons that motivated the multi-channel approach was the definition of PC and AC at each time point. We found that the transfer of information occurs with a delay that is inversely proportional to the frequency of the signal, a time scale that is much shorter than the ideal time window used for the measures of connectivity. These time scales are much longer than the synaptic delay within areas, which are typically on the order of a few milliseconds26,27. Analyzing the delays relative to one oscillation period, we observed that within the 1–2 Hz band, this corresponds to approximately 2p/3 of the period. For the 2–4 Hz band, this equates to approximately p, and within the 4–8 Hz band, this value increases to approximately 2p. These findings lead us to two conclusions. First, they validate our hypothesis regarding causal interactions manifesting within time scales comparable to oscillation periods, emphasizing the necessity for time-resolved measurements. Second, the observed increase in relative delay at higher frequency bands implies the involvement of components at lower frequencies in the PC and AC, as illustrated in Fig. 1.D.

Our result that similar patterns of causality were observed in ongoing activity recorded by MEG as well is not obvious at all. First, the neural signal recorded by a single sensor in MEG reflects the activity of a much larger population than the recorded by our µECoG array, where the recorded signals are much better localized and arise from few cortical columns under the recording contact23,28. Second, the spatial extent covered by the 9 µECoG-electrodes and the 9 MEG-sensors was quite different; the separation between the most distant recording sites in the ferret was ~ 1 cm, whereas in the human data it was ~ 6 cm. The coverage proportion of the visual cortex was, however, comparable in both cases. This unveils a mechanism that operates across various scales and broad measures. Another result that reveals the scale-free properties of the mechanism is the similarity of the spectral characteristic for both, PC and AC across carrier frequency bands (Fig. 1.D). The character of the PC and AC as function of frequency resembles the ~ 1/f power-law distribution ubiquitous to self-organized criticality29.

Although the goal of our study was not the detailed computational simulation of the relation between PC and AC, we explored to what extent a simplistic, non-biological system can predict the observed phenomena. We started with a model of coupled linear oscillator with noise. Contrary to established models like Kuramoto’s model, our goal was not to explicitly describe effects like synchronization30. Our model, however, predicts statistical distribution of AC, PC and their joint probabilities that resemble the ones observed experimentally. We see two possible scenarios that may explain the transient events of desynchronization in PC observed in our model. The first one would be a variation in the delay that is different for each connection31. This scenario, though, would imply jittering in delay at least comparable with the time scale of the frequency band. For instance, jittering in 2–4 Hz band would require jittering of ~ 100 ms to introduce desynchronization. Since changes in the delay are not taken explicitly into account by our model, the fact that the simulation predicts such variation suggests to us that they are due to the close similarity in the spectral properties of the oscillators, which in our case are defined by mass mi and coupling constants kij. Furthermore, one possibility that may explain why our computational model reproduces the probability distributions and the causal relations is the fact that we considered all-to-all weak interactions. Finally, the fact that surrogate data do not emulate this result demonstrates that the causality is not induced by the statistical characteristics of the function, but reflects a physical property of the system.

In conclusion, our results show a causal relation between global representations of phase and amplitude consistency across neural populations. We hypothesize that this relation is an inherent mechanism of brain dynamics and its functional role may be the associated with events that require the coordinated action of global phase and amplitude. In a recent study, Galinsky and Frank32, using a network of nonlinear oscillatory propagating modes, demonstrated that the emergence of collective synchronized spiking activity was possible only when both phase and amplitude were taken into account. The present results clearly indicate a causal impact of amplitude coupling on phase coupling, which raises the question of the putative functional relevance of such an interaction. We have previously suggested that amplitude coupling modes, reflecting correlated excitability fluctuations, may serve to gate, or facilitate, faster phase coupling of neural oscillations2,33. This is compatible with recent modeling work indicating that scale-free amplitude fluctuations can have an important influence on long-range phase coupling. Such critical systems operate at the balance between excitation and inhibition, which enhances its dynamic range, allowing for fast reconfigurations of functional connectivity34. Thus, we may speculate that the transfer from AC to PC may be altered in neurological disorders with excessive excitation or synchronization, such as in epilepsy35. Resolving the origin and the potential functional implications of interactions between amplitude and phase coupling awaits future research, possibly requiring specific interventions that can separately target these coupling modes.

Materials and methods

Electrophysiological recording of ferret data

Data recorded from 7 freely behaving female ferrets (Mustela putorius furo) were used for the present study. A detailed description of housing, implantation of µECoG arrays and recording procedures have been already reported in12. Briefly, a custom designed µECoG with 64 electrodes array was implanted over the cortex of the left hemisphere (Fig. 1). Before the excised piece of bone was place back in place, we took photographs of the distribution of array contacts on the cortex to assign the position of each electrode to one of 16 anatomical areas based on the map generated by16. For later analysis we assigned the anatomical areas into 3 main groups comprising visual, auditory and parietal areas, respectively. After recovery (~ 7 days) the animal was accustomed to a sound attenuated chamber where the experiments were performed. ECoG signals were digitized at 1.4 kHz (0.1 Hz high pass and 357 Hz low pass filters), and sampled simultaneously with a 64 channel AlphaLab SnRTM recording system (Alpha Omega Engineering, Israel). During the recording sessions the animals were able to move freely, and movements were monitored with an accelerometer mounted to the cable-interface attached to the head. Further information on animal’s preparation, housing and array implantation can be found in12.

MEG recording of human resting state data

MEG resting state data were acquired using a 275-channel whole-head system (CTF MEG International Services LP, Coquitlam, Canada) in a magnetically shielded chamber. For this study, we used resting-state measurements in 10 healthy adult subjects, each of whom maintained the eyes closed for an approximate duration of 10 min. Prior to their involvement, all participants provided their informed consent in written form. The local ethics committee (Ethik-Kommission der Ärztekammer Hamburg) granted approval for all employed methods, and all procedures were executed in strict adherence to the stipulations of the Declaration of Helsinki. The data utilized in this study were originally collected for a distinct research project. Data acquisition was conducted at a sampling rate of 1200 Hz, and data were offline down-sampled to 300 Hz for subsequent analysis.

Analysis of ferret data and brain state classification

All data analysis procedures were implemented either with MatLab (Mathworks, Natick, MA) or in Python. All intervals in which recorded signals were larger than 10 standard deviations were considered as noise and consequently rejected for further analysis. Each signal was re-referenced by subtracting the average signal across all 64 channels to remove potential artifacts and reduce effects of volume conduction. Signals were filtered in steps of 2 Hz with a butterworth filter (2th and 4th order). To reduce dimensionality for the analysis, the filtered signals were gathered into 7 frequency bands ranging from 1 to 2, 2–4, 4–8, 8–16, 16–32, 32–64 and 64–128 Hz, respectively. Within each frequency the resultant signal was z-scored to normalize amplitude fluctuations across frequency bands and electrodes.

Ongoing behaviors display fluctuations in power spectral characteristics that often can be associated with changes in states of the brain. To classify brain states we used a procedure that we have applied previously12. We performed a power spectral analysis for all individual channels on sliding time-windows (30 s) and calculated the global mean spectrogram. This procedure was repeated in sliding windows of 5 s. Subsequently, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to reduce dimensionality and, finally, a clustering analysis was applied (k-means) to extract 3 main clusters that we identified as distinct brain states. The number of states was based on the quality of different number of clusters, as we showed in a previous study12.

Analysis of MEG data

In order to make a fair comparison with the ferret data, we selected a cluster of 9 sensors located in the most occipital region of the left hemisphere. The signals were down-sampled to 300 Hz and then filtered into 7 frequency bands as follows: 1–2, 2–4, 4–8, 8–16, 16–32, 32–64, and 64–100 Hz. Within each frequency band, the resultant signal was z-scored to normalize amplitude fluctuations across electrodes. Brain-state analysis was not performed in the human data as the recording duration was too short for this purpose.

Time resolved phase- and amplitude consistency

Standard measures of connectivity, such as amplitude correlations or coherence, are defined for pairs of recording sites (e.g., electrodes or brain regions of interest) during a time-window which can vary in duration from sub-seconds to minutes. However, for the study of the causal relation between phase and amplitude coupling modes we considered it convenient to introduce instantaneous measures that can be defined at each time t’, rather than for an extended time window. Here, we propose an approach based on the assumption that strong phase (amplitude) coupling is reflected in a less variable relation of phases (amplitudes) across sets of recording sites. Conceptually similar to the phase-locking value (PLV), which reflects how consistent the phase related to a particular stimulus event is across trials15, we took signals of multiple electrodes and measured the consistency of the phase relation across recording sites defined as:

with \(\:{\varphi}_{k}\left(t\right)\) the phase of channel k at time t, and N the number of channels. This value by itself does not say much about the connectivity. Assuming that there is a perfect phase correlation between the signals, the PC can take any value between 0 and 1. Applying the same rationale to the signal amplitudes, we defined amplitude consistency (AC) as:

where \(\:\mu\left(t\right)\) denotes the mean amplitude at time t, computed by averaging the instantaneous amplitudes derived from the absolute values of the Hilbert transform. σ represents the standard deviation at time t. Instantaneous phase and amplitude were computed after applying the Hilbert transform to the filtered signal s. Note that a consistent phase relation between channels can take any arbitrary value between 0 and 1, and whether the phase-relation remains constant (as an indicator of connectivity) is indicated by a low temporal variation of PC.

Causality measure

We used transfer entropy (TE) to determine the causal relation between phase-based (PC) and amplitude-based (AC) time series. TE measures the directed transfer of information between two non-parametric time-series X and Y, and is defined as the information shared between the past of X and the present of Y present, given Y’s past17:

Here we calculated TE in both directions, namely, PC playing the role of leader and AC the follower, and vice versa. Both quantities were calculated separately for non-overlapping time-windows of 30 s and for all frequency bands. The statistical significance test was based on the null-hypothesis of no source-target interaction19,36, with time-randomized leader and follower. These surrogates were created from the same set of observations (leader’s interval) maintaining the same distribution but with temporal dependency of the source destroyed. For each individual interval we selected the significance level as the mean plus two times the standard deviation. We selected the highest significance level across intervals and animals. TE was calculated in Python using the open-source implementation PyIF37.

Computational simulation

To study whether a relation between PC and AC, if any, is caused by some biological effect or not, we simulated a non-biological system of coupled oscillators or springs, in which the interaction obeys Hooke’s law:

where mi is the mass, kij the coupling constant between nodes i and j, and εi is a noise factor. In the model, we allowed all-to-all interactions between oscillators, rather than only first neighbors. To directly compare with the experimental results, we simulated a system of 9 oscillators randomizing the parameters in each run. Parameter’s estimation ki, mi and εi was achieved after applying a modest amount of hand-tuning that delivered reasonable predictions. We implemented the following set of parameters: \(\:{k}_{i}=3\pm\:0.1\), \(\:{m}_{i}=4\pm\:0.2\) and \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}=0\pm\:0.5\). We solved the system of coupled differential equations using the function ODE45 in MatLab.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Change history

23 July 2025

This article has been updated to amend the license information.

References

Nolte, G. et al. Identifying true brain interaction from EEG data using the imaginary part of coherency. Clin. Neurophysiol. 115, 2292–2307 (2004).

Engel, A., Gerloff, C., Hilgetag, C. & Nolte, G. Intrinsic coupling modes: multiscale interactions in ongoing brain activity. Neuron 80, 867–886 (2013).

Brookes, M. J. et al. Measuring functional connectivity using MEG: methodology and comparison with FcMRI. NeuroImage 56, 1082–1104 (2011).

Hipp, J., Hawellek, D., Corbetta, M., Siegel, M. & Engel, A. Large-scale cortical correlation structure of spontaneous oscillatory activity. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 884–890 (2012).

Fornito, A., Zalesky, A. & Breakspear, M. The connectomics of brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 159–172 (2015).

Siegel, M., Donner, T. H. & Engel, A. K. Spectral fingerprints of large-scale neuronal interactions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 121–134 (2012).

Galindo-Leon, E. et al. Context-specific modulation of intrinsic coupling modes shapes multisensory processing. Sci. Adv. 5, eaar7633 (2019).

Siems, M. & Siegel, M. Dissociated neuronal phase- and amplitude-coupling patterns in the human brain. NeuroImage 209, 116538 (2020).

Nolte, G., Galindo-Leon, E., Li, Z., Liu, X. & Engel, A. Mathematical relations between measures of brain connectivity estimated from electrophysiological recordings for Gaussian distributed data. Front. Neurosci. 14, 577574 (2020).

Mercier, M. R. et al. Auditory-driven phase reset in visual cortex: human electrocorticography reveals mechanisms of early multisensory integration. NeuroImage 79, 19–29 (2013).

Rule, M. E., Vargas-Irwin, C., Donoghue, J. P. & Truccolo, W. Phase reorganization leads to transient β-LFP Spatial wave patterns in motor cortex during steady-state movement Preparation. J. Neurophysiol. 119, 2212–2228 (2018).

Stitt, I. et al. Dynamic reconfiguration of cortical functional connectivity across brain States. Sci. Rep. 7, 8797 (2017).

Hindriks, R. & Tewarie, P. Dissociation between phase and power correlation networks in the human brain is driven by co-occurrent bursts. Commun. Biol. 6, 286 (2023).

Liuzzi, L. et al. How sensitive are conventional MEG functional connectivity metrics with sliding windows to detect genuine fluctuations in dynamic functional connectivity? Front. Neurosci. 13, 797 (2019).

Lachaux, J., Rodriguez, E., Martinerie, J. & Varela, F. Measuring phase synchrony in brain signals. Hum. Brain Mapp. 8, 194–208 (1999).

Bizley, J., Nodal, F., Bajo, V., Nelken, I. & King, A. Physiological and anatomical evidence for multisensory interactions in auditory cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 17, 2172–2189 (2007).

Schreiber, T. Measuring information transfer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 461–464 (2000).

Vicente, R., Wibral, M., Lindner, M. & Pipa, G. Transfer entropy—a model-free measure of effective connectivity for the neurosciences. J. Comput. Neurosci. 30, 45–67 (2011).

Lizier, J., Heinzle, J., Horstmann, A., Haynes, J. & Prokopenko, M. Multivariate information-theoretic measures reveal directed information structure and task relevant changes in fMRI connectivity. J. Comput. Neurosci. 30, 85–107 (2011).

Ursino, M., Ricci, G. & Magosso, E. Transfer entropy as a measure of brain connectivity: A critical analysis with the help of neural mass models. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 14, 45 (2020).

Keskin, Z. & Aste, T. Information-theoretic measures for nonlinear causality detection: application to social media sentiment and cryptocurrency prices. R Soc. Open. Sci. 7, 200863 (2020).

Schreiber, T. & Schmitz, A. Improved surrogate data for nonlinearity tests. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 635–638 (1996).

Bockhorst, T. et al. Synchrony surfacing: epicortical recording of correlated action potentials. Eur. J. Neurosci. 48, 3583–3596 (2018).

Canolty, R. & Knight, R. The functional role of cross-frequency coupling. Trends Cogn. Sci. 14, 506–515 (2010).

Cabral, J. et al. Metastable oscillatory modes emerge from synchronization in the brain spacetime connectome. Commun. Phys. 5, 184 (2022).

Feldmeyer, D., Roth, A. & Sakmann, B. Monosynaptic connections between pairs of spiny stellate cells in layer 4 and pyramidal cells in layer 5A indicate that lemniscal and paralemniscal afferent pathways converge in the infragranular somatosensory cortex. J. Neurosci. 25, 3423–3431 (2005).

Gourévitch, B. & Eggermont, J. Evaluating information transfer between auditory cortical neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 97, 2533–2543 (2007).

Bockhorst, T., Engel, A. & Galindo-Leon, E. What do ECoG recordings tell us about intracortical action potentials? in Intracranial EEG (ed. Axmacher, N.) 283–295Springer International Publishing, Cham, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20910-9_18

Shew, W. & Plenz, D. The functional benefits of criticality in the cortex. Neuroscientist 19, 88–100 (2013).

Kuramoto, Y. Self-entrainment of a population of coupled non-linear oscillators. in International Symposium on Mathematical Problems in Theoretical Physics (ed. Araki, H.) vol. 39 420–422 (Springer-Verlag, Berlin/Heidelberg, (1975).

Haken, H. Effect of delay on phase locking in a pulse coupled neural network. Eur. Phys. J. B. 18, 545–550 (2000).

Galinsky, V. & Frank, L. Collective synchronous spiking in a brain network of coupled nonlinear oscillators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 158102 (2021).

Engel, A. K. & Gerloff, C. Dynamic functional connectivity: causative or epiphenomenal? Trends Cogn. Sci. 26, 1020–1022 (2022).

Palva, S. & Palva, J. M. Roles of brain criticality and multiscale oscillations in Temporal predictions for sensorimotor processing. Trends Neurosci. 41, 729–743 (2018).

Arnulfo, G., Hirvonen, J., Nobili, L., Palva, S. & Palva, J. M. Phase and amplitude correlations in resting-state activity in human stereotactical EEG recordings. NeuroImage 112, 114–127 (2015).

Verdes, P. Assessing causality from multivariate time series. Phys. Rev. E. 72, 026222 (2005).

Ikegwu, T. & Brunner, R. J. McMullin PyIF: A fast and light weight implementation to estimate bivariate transfer entropy for Big Data. (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the DFG (SFB936-178316478-A2/Z3, SPP1665-EN533/13-1, SPP2041-EN533/15-1) and by the European Union (project cICMs, ERC-2022-AdG-101097402).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EEGL, FP, and AKE conceived and designed experiments. FP surgically implanted arrays. FP, EEGL and GE performed experiments. EEGL and GN analyzed data. GE wrote the animals ethics permission. EEGL and AKE wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Galindo-Leon, E.E., Nolte, G., Pieper, F. et al. Causal interactions between amplitude correlation and phase coupling in cortical networks. Sci Rep 15, 11975 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95306-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95306-1