Abstract

While the potential of immunological biomarkers as an alternative to aid in the diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of sarcopenia has been explored, there are still few studies evaluating their diagnostic accuracy. Specific biomarkers and diagnostic cutoff points remain unknown. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to verify the association between sarcopenia and a panel of inflammatory biomarkers and to investigate the diagnostic accuracy to propose cutoff points for this assessment. Accordance with EWGSOP2 guidelines, 71 community-dwelling older women participated in the study and were assessed for sarcopenia diagnosis. Dual-energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA), a Jamar dynamometer, and the Short Physical Performance Battery were used for diagnosis and classification of sarcopenia. A panel of biomarkers, including adiponectin, BDNF, IFN, IL-2, -4, -5, -6, -8, -10, leptin, resistin, TNF-α, and their soluble type 1 and 2 receptors, was measured using ELISA and flow cytometry. The associations between sarcopenia and a panel of biomarkers were verified by logistic regression analysis, and the cutoff points were determined using the ROC curve and Youden index. The sTNFr-2 was significantly associated with sarcopenia, showed good diagnostic accuracy and the optimal discriminatory cutoff point (AUC = 0.75) found was 2280 pg/ml in community-dwelling older women. These results provide valuable insights for the diagnosis, monitoring and understanding of the pathophysiology of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sarcopenia is a progressive, generalized, age-related muscle disease characterized by declines in muscle strength, lean muscle mass, and physical functional performance in older adults. This condition can lead to a loss of functional independence, increased disability, higher rates of hospitalization, and elevated mortality1,2. The European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2) has issued recommendations for screening and diagnosis of sarcopenia and its stages3. These guidelines include a diagnostic algorithm that involves evaluating muscle strength, muscle mass and functional physical performance in older individuals3. Muscle weakness is proposed as the primary indicator for this condition3. For diagnosis, reductions in muscle quantity and/or quality must be confirmed3. The severity of sarcopenia is then defined by the presence of muscle weakness, low muscle quantity/quality, and poor functional performance as assessed by Gait Speed (GS), Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), or Timed Up and Go test (TUG)3.

Sayer & Cruz-Jentoft (2022) highlighted that many healthcare professionals do not consistently use established criteria for sarcopenia screening and diagnosis, often lacking awareness of the most recommended diagnostic tools and instruments2. Additionally, access to essential tools, such as dynamometers for measuring muscle strength or techniques like Dual-energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA) for assessing muscle mass, is limited in many clinical settings2,3,4. Given these limitations, the development of alternative strategies, including the use of biomarkers to assess sarcopenia, has been strongly recommended5,6,7.

Inflammation and neuroinflammation are recognized is a key component of pathophysiological of sarcopenia in older8,9,10. Chronic low-grade inflammation, often referred to as inflammaging, progresses with age and is characterized by elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the bloodstream, which are associated with muscle catabolism and adverse health outcomes8. In this context, recent literature reviews have compiled evidence on potential biomarkers that may characterize inflammation in older individuals, aiding clinicians and researchers in detecting sarcopenia5,6,8,9,10,11.

Several inflammatory mediators have been studied and reported to be associated with sarcopenia and its stages in older adults, such as adiponectin, leptin, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), interleukins 6, 8 and 10, tumoral necrosis factor (TNF) and its soluble receptors (sTNFr) types 1 and 2,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Although associations between inflammatory mediators and sarcopenia have been reported, there are several gaps in literature regarding their diagnosis using blood biomarker analysis6,9,10,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Considering the multifactorial nature of sarcopenia and the numerous pathways involved in its development, no single biomarker or cutoff value has been identified for diagnosis via biomarker analysis10,11,20. Furthermore, exploratory research has been encouraged to investigate the potential of biomarker panels, which may allow for the examination of alternative inflammatory pathways involved in the etiology of sarcopenia6,10,11,20,22,23.

Accordingly, the present study aimed to evaluate the association between sarcopenia and plasma concentrations of adiponectin, BDNF, IFN, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, leptin, resistin, TNF, sTNFr-1 and 2. Additionally, it sought to verify the diagnostic accuracy of these markers for sarcopenia screening in community-dwelling older women. The study also aimed to contribute to improved screening strategies, clinical diagnosis of sarcopenia, and understanding of its underlying pathophysiology.

Methods

Sample

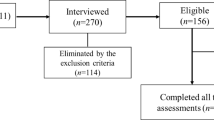

The sample name, address and telephone, was obtained through registrations in all primary health care units in Diamantina, MG, Brazil. A survey of the number of possibly eligible older women was carried out and all were visited in their homes. After checking the eligibility criteria, the informed consent was obtained from all subjects and they were invited to participate in the evaluation procedures in the laboratories of the integrated center for research and postgraduate studies in health (CIPQ) at Federal University of Jequitinhonha e Mucuri Valleys (UFVJM). The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Research and Ethics Committee of UFVJM (protocol code 1,461,306 on March 22, 2016). This manuscript was prepared according to the recommendations of the Standards for Reporting Diagnostic accuracy studies (STARD)24,25 and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE).

Procedures

The evaluations took place from June 2016 to June 2017 and occurred in 3 stages on 3 different days. The first involves a home visit to sign the consent form, provide guidance on upcoming procedures, and check the eligibility criteria. Inclusion criteria were women aged 65 years or older, functionally independent in the community and able to complete the study assessments. The exclusion criteria were: older women who presented cognitive dysfunction assessed by the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE); those with neurological sequelae; those who were hospitalized less than 3 months ago; who had fractures in the lower or upper limbs less than 6 months ago; who presented acute musculoskeletal disorders that interfered with the proposed physical assessments; patients with acute respiratory or cardiovascular diseases; who presented inflammatory disease in the acute phase; active neoplasia in the last 5 years; in palliative care; who used anti-inflammatory medications or those that act on the immune system; and those with significant visual or hearing deficits that made it impossible to carry out the proposed procedures.

Assessment of sarcopenia

On the second day, the participants were taken in the morning (8 a.m.) to the UFVJM laboratories where they were initially evaluated regarding weight (kg) and height (m) using a weighing-machine (Welmy) with an attached stadiometer. Subsequently, they underwent a body composition examination using Dual X-Ray Absorptiometry (Lunar Radiation Corporation, Madison, Wisconsin, EUA, model DPX) for assessment of Sarcopenia3. Afterwards, they had a standardized snack for all participants, and after 15 min they began strength and physical function tests. Muscle strength was assessed using a Jamar dynamometer, and physical performance was assessed using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB)3. The Classification followed the recommendations of EWGSOP2, using cutoff points of 20kgf to evaluate low muscle strength3,26, Skeletal Muscle Mass Index (SMI) ≤ 5.5 kg/m2 and physical performance SPPB < 8 points3. Thus, the sample was divided into 4 groups: No Sarcopenia, Probable Sarcopenia, Sarcopenia and Severe Sarcopenia.

Biomarker panel

On the third day, 24 h after body composition and physical function assessments, the participants were taken to the laboratory for blood collection. Blood was collected at 8 a.m., (10 ml from the antecubital fossa of the upper limb with disposable material) after the participants fasted from food, liquid, and medication for 10 h. Samples were collected in vacutainer bottles with heparin in a sterile environment. Immediately after this procedure, the samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm in a centrifuge for 10 min. Plasma samples were extracted and kept at − 80 °C for 6 months before being analyzed. Plasma concentrations of IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, TNF-α, adiponectin, leptin, resistin, BDNF, sTNFr-1 and sTNFr-2 were analyzed by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique (Duo- Sep, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA). Plasma levels of IL-6, IL-8, and IFN-γ were measured using cytometric bead arrays kit (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were acquired on a FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD Bioscience) and analyzed using the FCAP array v1.0.1 software (Soft Flow)27.

Statistical analysis

Openepi software (www.openepi.com) was used to determine the sample size, considering a prevalence of sarcopenia of 16%28, an effect size of 0.80, a significance level of 5% and a confidence interval of 80%, a sample size of 71 was achieved. More details about the sample calculation have already been published elsewhere29. For the statistical analyzes of this work, the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Statistics, version 22.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and Med-Calc Statistical (Med-Calc Software, version 13.1, Ostend, Belgium) software were used. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to verify data normality. In the present work, logistic regression analysis was conducted to verify the association between the biomarker panel and Sarcopenia. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were checked to test the sensitivity and specificity of the biomarker panel in identifying sarcopenia. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) and the 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for all tests and the optimal cut-off points were determined by the Youden Index30. An AUC greater than 0.7 was considered acceptable, while an area greater than 0.8 was considered excellent for the proposed cutoff points31. The level of statistical significance adopted was 5%.

Results

Seventy-one older women completed all assessment procedures and participated in the present study. The diagnosis of probable sarcopenia was 23.9%, confirmed sarcopenia was 19.7%, and severe sarcopenia was 11.3% of the sample. The baseline characteristics of sample and the distribution of the biomarker panel among the groups of older women without sarcopenia, with probable, confirmed and severe sarcopenia have been previously published14,29. In the logistic regression analysis, probable and confirmed sarcopenia were significantly associated with sTNFr-2 concentrations, and no biomarker was significantly associated with severe sarcopenia (Table 1).

The associations between sTNFr-2 and confirmed sarcopenia remained significant after the model was adjusted for participants’ age, % of fat and BMI. Figure 1 graphically presents the area under the curve (AUC) with its respective value along with the asymptotic 95% confidence interval.

To assess the discriminatory power for identifying older individuals with sarcopenia, we compared the diagnostic outcomes when the sample was classified using the EWGSOP2 algorithm against detection based on plasma sTNFr-2 concentrations. The methods were concordant in 58% of cases, correctly ruling out sarcopenia, and in 18% of cases, correctly identifying its presence. In this comparison, we observed that the sTNFr-2-based diagnosis yielded 11% of false positives and 12% of false negatives (Table 2). Nevertheless, the measures demonstrated significant agreement (kappa = 0.43; p < 0.001).

Table 3 summarizes the values of the positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV), sensitivity and specificity regarding the ability of sTNFr-2 to discriminate sarcopenia. No biomarker presented an acceptable area under the curve (AUC > 0.7) in detecting probable Sarcopenia and severe sarcopenia. In detecting confirmed Sarcopenia, sTNFr-2 demonstrated good specificity (84%), with an 82% probability of sarcopenia not being present when the values obtained are lower than 2280 pg/ml (Table 3).

The Youden index to present the ideal cutoff point for biomarkers, which presented acceptable (AUC > 0.7) and significant (p < 0.05) AUC for detecting confirmed sarcopenia in community dwelling older woman (Fig. 1).

Discussion

This study demonstrated a significant association between sarcopenia and plasma sTNFr-2 concentrations, highlighting its potential utility as a biomarker for the detection of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older women. The analysis revealed a specificity of 84%, indicating that sTNFr-2 could serve as a promising tool for sarcopenia screening. Moreover, plasma sTNFr-2 concentrations exceeding 2280 pg/ml were identified as a discriminatory cutoff threshold, which could be integrated into diagnostic strategies for sarcopenia in this population.

Sarcopenia is recognized and widely studied, but there is still extensive discussion in the literature regarding its clinical diagnosis, and the most accurate tools for its detection6,32,33,34,35. For example, a study demonstrated that the main instruments recommended by EWGSOP2 for assessing the stages of sarcopenia do not present good agreement with each other36,37. And studies that compare the prevalence of sarcopenia using the same assessment instruments, but different algorithms find substantially different results, under-diagnosis or misdiagnosis of the disease may occur36,38,39. In this context, practical and accurate alternatives for diagnosing sarcopenia have been a topic of significant relevance in the literature6,10,20.

Although the main global consensuses on sarcopenia (AWGS, EWGSOP, FNIH, IWGS) encourage studies with biomarkers3,40,41,42, and advances in research point to possible diagnostic markers3,32,41,42,43, diagnostic accuracy studies with inflammatory mediators are relatively recent and scarce, and a marker with an established cutoff point has not been found either6,10,11,22,44. Therefore, our results may be useful for clinicians, researchers and for updating new recommendations on the screening and diagnosis of sarcopenia in older women.

No studies were identified that established a reference range for sTNFr-2 concentrations, especially in community-dwelling older women, making it challenging to compare our findings with previous literature. Nevertheless, in the present investigation, among a panel of inflammatory biomarkers, only sTNFr-2 levels showed a significant association with sarcopenia. This finding allows us to hypothesize that sTNFr-2 can contributes to muscle damage, characterized by reductions in muscle strength and mass, potentially through mechanisms that remain poorly understood6,8,10,45.

It is well-established that TNF-α is an inflammatory cytokine that plays a central role in modulating inflammation and signaling pathways involved in macrophage survival and apoptosis, both of which are critical to the immune response and inflammatory processes46. Beyond its immunological functions, TNF-α interferes with muscle regeneration by suppressing the differentiation and proliferation of satellite cells, which are essential for muscle repair and growth45,47. Additionally, TNF-α can activate the ubiquitin–proteasome system, a primary pathway responsible for muscle proteins degradation, contributing to muscle mass loss8,45,48. Wang et al.49, demonstrated that myeloid cell-derived TNF-α contributes to muscle aging by affecting sarcopenia and muscle cell fusion with aged muscle fibers. Their findings further suggest that muscle-intrinsic TNF-α and immune cell-secreted TNF-α act synergistically to exacerbate muscle aging49. Similarly, TNF-α and its receptors, are associated with the activation of pathways that promote muscle protein degradation9,45, suggesting a role in age-related inflammation and sarcopenia, although the specific mechanisms remain unknown.

TNF-α exerts its effects through its receptors, sTNFr-1 and sTNFr-2, which mediate a range of inflammatory responses, and have been reported to play distinct yet interrelated roles46. Studies show a complex and paradoxical interplay between the action of sTNFr-1 and 2 in inflammatory contexts50. Evidence indicates that both receptors exhibit pro-inflammatory characteristics and are found in higher concentrations in individuals with chronic inflammatory conditions, such as fibromyalgia51, osteoarthritis52, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease27, and in older people with chronic low back pain48. While sTNFr-1 appears to mediate inflammatory cross talk between muscle and adipose tissue potentially contributing to decrease intrinsic capacity and sarcopenia53, previous studies have suggested that sTNFr-2 have as a biomarker related to the diagnosis and its severity in older women14,15.

The sTNFr-2 is a soluble form of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor type 2, capable of binding to and modulating circulating TNF46. This receptor regulates TNF activity by preventing its interaction with cellular receptors, thereby influencing the inflammatory response45,46. Elevated levels of sTNFr-2 may signal prolonged TNF-α activity, which impairs the body’s ability to regenerate muscle tissue effectively45,46,47,52. However, its role in inflammation remains controversial, as evidence in the literature presents conflicting perspectives54,55. Some studies suggest that sTNFr-2 functions as an anti-inflammatory mediator, playing a role in oligodendrocyte survival and axonal myelination. Furthermore, recent findings highlight its therapeutic potential in managing Multiple Sclerosis and cancer56,57,58. In preclinical studies, this marker has demonstrated dose-dependent effects on skeletal muscle atrophy, modulation of neuropathic pain, and potential as an anti-tumor therapy46,47,57,59.

On the other hand, there is growing evidence suggesting that sTNFr-2 can play a dichotomous role in the control or exacerbation of inflammation50,60. Recent studies clarify that this biomarker is involved in various conditions, including diabetic neuropathy, lupus, and cancer46,50,60,61. In many of these contexts, sTNFr-2 contributes to an inflammatory environment that favors the worsening of all these conditions46,50,62,63. Studies investigating its therapeutic potential demonstrate that suppressing sTNFr-2 expression pathways positively impacts the regulation of the inflammatory environment, potentially hindering metastasis progression in cancer60,63. Another study highlights the complex and contrasting roles of soluble TNF receptors 1 and 2, particularly in natural killer (NK) cells within inflammatory responses60. Results revealed a dichotomous effect of sTNFr-1 and sTNFr-2 on NK cells, with sTNFr-1 inducing NK cell death and reduced their accumulation, while sTNFr-2 promoted their accumulation50,60. Therefore, it is reasonable to suggest that relationship between sarcopenia and sTNFr-2 is mediated by its role in modulating inflammation, contributing to an inflammatory environment that favors inflammatory exacerbation and muscle catabolism, and may serve as an indicator of the chronic inflammatory response associated with muscle wasting and weakness in sarcopenia18,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71.

Although our results refer to the diagnostic components of sarcopenia, they may be useful in the diagnosis of other conditions in which loss of lean muscle mass, muscle strength and functional physical performance are involved6,10,20. In clinical practice the cutoff point of 2280 pg/ml for plasmatic concentrations of sTNFr-2 can be used in screening and diagnostic strategies for sarcopenia, and for monitoring the inflammatory status of older women. Contributing to early diagnosis strategies and integrated care for the older people72, considering that inflammation can contribute to the development of a series of chronic conditions, especially in the aging.

Our study has some limitations that need to be considered. These results should be considered preliminary due to the cross-sectional design that prevents inferring a cause-and-effect relationship between the variables. The sample was small, so it is important to replicate these analyses in nationally representative samples, and represented only by females can also be considered a limitation, but also a strength, as the differences in the inflammatory profile during aging between females and males are different12,21,64,73. Another point that can be highlighted is the fact that the population is community-dwelling older women, and these results cannot be extended to older people in other environments, such as clinics and outpatient clinics, hospital or institutionalized, or older with secondary sarcopenia. Finally, further research is necessary to address the existing gap in understanding the role of sTNFr-2 and inflammatory pathways activated in sarcopenia and/or their interactions with other inflammatory mediators, which collectively contribute to the exacerbation of inflammation in skeletal muscle.

Conclusion

Soluble TNF type 2 receptors showed good diagnostic accuracy and specificity in screening for sarcopenia in community-dwelling older women. These insights may be useful in clinical sarcopenia screening strategies, especially when gold standard instruments are not available.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available to protect the privacy of participants but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yuan, S. & Larsson, S. C. Epidemiology of sarcopenia: Prevalence, risk factors, and consequences. Metabolism https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2023.155533 (2023).

Sayer, A. A. & Cruz-Jentoft, A. Sarcopenia definition, diagnosis and treatment: consensus is growing. Age Ageing https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac220 (2022).

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the extended group for EWGSOP2. Age Ageing 48, 16–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy169 (2019).

Cho, M. R., Lee, S. & Song, S. K. A review of sarcopenia pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment and future direction. J. Korean Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e146 (2022).

Kalinkovich, A. & Livshits, G. Sarcopenia—The search for emerging biomarkers. Ageing Res. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2015.05.001 (2015).

El-Sebaie, M. & Elwakil, W. Biomarkers of sarcopenia: An unmet need. Egypt. Rheumatol. Rehabil. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43166-023-00213-w (2023).

Aronson, J. K. & Ferner, R. E. Biomarkers—A general review. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpph.19 (2017).

Wang, T. Searching for the link between inflammaging and sarcopenia. Ageing Res. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2022.101611 (2022).

Pan, L. et al. Inflammation and sarcopenia: A focus on circulating inflammatory cytokines. Exp. Gerontol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2021.111544 (2021).

Ladang, A. et al. Biochemical markers of musculoskeletal health and aging to be assessed in clinical trials of drugs aiming at the treatment of sarcopenia: Consensus paper from an expert group meeting organized by the European Society for Clinical. Calcif. Tissue Int. 112, 197–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-022-01054-z (2023).

Curcio, F. et al. Biomarkers in sarcopenia: A multifactorial approach. Exp. Gerontol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2016.09.007 (2016).

Komici, K. et al. Adiponectin and sarcopenia: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.576619 (2021).

Yang, Z. Y. & Chen, W. L. Examining the association between serum leptin and sarcopenic obesity. J. Inflamm. Res. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S320445 (2021).

da Costa Teixeira, L. A. et al. Inflammatory biomarkers at different stages of sarcopenia in older women. Sci. Rep. 13, 10367. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-37229-3 (2023).

Lustosa, L. P. et al. Comparison between parameters of muscle performance and inflammatory biomarkers of non-sarcopenic and sarcopenic elderly women. Clin. Interv. Aging https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S139579 (2017).

Rong, Y. D., Bian, A. L., Hu, H. Y., Ma, Y. & Zhou, X. Z. Study on relationship between elderly sarcopenia and inflammatory cytokine IL-6, anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. BMC Geriatr. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-1007-9 (2018).

Bian, A. L. et al. A study on relationship between elderly sarcopenia and inflammatory factors IL-6 and TNF-α. Eur. J. Med. Res. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-017-0266-9 (2017).

Teixeira, L. A. C. et al. Inflammatory biomarkers in older women with obesity, sarcopenia, and sarcopenic obesity. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2023.05.022 (2023).

Rossi, F. E. et al. Influence of skeletal muscle mass and fat mass on the metabolic and inflammatory profile in sarcopenic and non-sarcopenic overfat elderly. Aging Clin. Exp. Res 31, 629–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-018-1029-3 (2019).

Jones, R. L., Paul, L., Steultjens, M. P. M. & Smith, S. L. Biomarkers associated with lower limb muscle function in individuals with sarcopenia: A systematic review. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13064 (2022).

Singh, T. & Newman, A. B. Inflammatory markers in population studies of aging. Ageing Res. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2010.11.002 (2011).

Kwak, J. Y. et al. Prediction of sarcopenia using a combination of multiple serum biomarkers. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26617-9 (2018).

Karim, A., Iqbal, M. S., Muhammad, T. & Qaisar, R. Evaluation of sarcopenia using biomarkers of the neuromuscular junction in Parkinson’s disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12031-022-01970-7 (2022).

Bossuyt, P. M. et al. STARD 2015: An updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. Clin. Chem. 2015, 61. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2015.246280 (2015).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013 (2014).

Soares, L. A. et al. Accuracy of handgrip and respiratory muscle strength in identifying sarcopenia in older, community-dwelling, Brazilian women. Sci. Rep. 13, 1553. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28549-5 (2023).

Neves, C. D. C. et al. Inflammatory and oxidative biomarkers as determinants of functional capacity in patients with COPD assessed by 6-min walk test-derived outcomes. Exp. Gerontol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2021.111456 (2021).

Diz, J. B. M. et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia in older Brazilians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12720 (2017).

Augusto Costa Teixeira, L. et al. Clinical medicine adiponectin is a contributing factor of low appendicular lean mass in older community-dwelling women: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 7175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237175 (2022).

Youden, W. J. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1%3c32::AID-CNCR2820030106%3e3.0.CO;2-3 (1950).

Hajian-Tilaki, K. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for medical diagnostic test evaluation. Caspian J. Intern. Med. 4, 627 (2013).

Petermann-Rocha, F. et al. Global prevalence of sarcopenia and severe sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12783 (2022).

Kirk, B. et al. The conceptual definition of sarcopenia: Delphi Consensus from the global leadership initiative in sarcopenia (GLIS). Age Ageing https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afae052 (2024).

Coletta, G. & Phillips, S. M. An elusive consensus definition of sarcopenia impedes research and clinical treatment: A narrative review. Ageing Res. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.101883 (2023).

Fielding, R. A. et al. Sarcopenia: An undiagnosed condition in older adults. Current consensus definition: Prevalence, etiology, and consequences. International Working Group on Sarcopenia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2011.01.003 (2011).

Sutil, D. V. et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia in older women and level of agreement between the diagnostic instruments proposed by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-06287-z (2023).

Purcell, S. A. et al. Sarcopenia prevalence using different definitions in older community-dwelling Canadians. J. Nutr. Health Aging https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1427-z (2020).

Shafiee, G. et al. Comparison of EWGSOP-1and EWGSOP-2 diagnostic criteria on prevalence of and risk factors for sarcopenia among Iranian older people: The Bushehr Elderly Health (BEH) program. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-020-00553-w (2020).

Fernandes, L. V. et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia according to EWGSOP1 and EWGSOP2 in older adults and their associations with unfavorable health outcomes: A systematic review. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-021-01951-7 (2022).

Chen, L. K. et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: Consensus report of the Asian working group for sarcopenia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.025 (2014).

Studenski, S. A. et al. The FNIH sarcopenia project: Rationale, study description, conference recommendations, and final estimates. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glu010 (2014).

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. et al. Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing adults: A systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS). Age Ageing https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu115 (2014).

Chen, L. K. et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.012 (2020).

Guo, A., Li, K. & Xiao, Q. Sarcopenic obesity: Myokines as potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets?. Exp. Gerontol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2020.111022 (2020).

Zelová, H. & Hošek, J. TNF-α signalling and inflammation: Interactions between old acquaintances. Inflamm. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-013-0633-0 (2013).

Wajant, H. & Siegmund, D. TNFR1 and TNFR2 in the control of the life and death balance of macrophages. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2019.00091 (2019).

Li, J. et al. TNF receptor-associated factor 6 mediates TNFα-induced skeletal muscle atrophy in mice during aging. J. Bone Miner. Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.4021 (2020).

Arrieiro, A. N. et al. Inflammation biomarkers are independent contributors to functional performance in chronic conditions: An exploratory study. Int. J. Med. Sci. Health Res. https://doi.org/10.51505/ijmshr.2021.5404 (2021).

Wang, Y., Welc, S. S., Wehling-Henricks, M. & Tidball, J. G. Myeloid cell-derived tumor necrosis factor-alpha promotes sarcopenia and regulates muscle cell fusion with aging muscle fibers. Aging Cell https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.12828 (2018).

Williams, R. O., Clanchy, F. I. L., Huang, Y. S., Tseng, W. Y. & Stone, T. W. TNFR2 signalling in inflammatory diseases. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 38, 101941. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BERH.2024.101941 (2024).

Ribeiro, V. G. C. et al. Inflammatory biomarkers responses after acute whole body vibration in fibromyalgia. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-431x20176775 (2018).

Simão, A. P. et al. Soluble TNF receptors are produced at sites of inflammation and are inversely associated with self-reported symptoms (WOMAC) in knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatol. Int. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-014-3016-0 (2014).

Augusto da Costa Teixeira, L. et al. The strong inverse association between plasma concentrations of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors type 1 with adiponectin/leptin ratio in older women. Cytokine https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2024.156512 (2024).

Xu, R. et al. TNFR2+ regulatory T cells protect against bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia by suppressing IL-17A-producing γδ T cells in the lung. Cell Rep. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112054 (2023).

Camara, M. L. et al. TNF-α and its receptors modulate complex behaviours and neurotrophins in transgenic mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.09.010 (2013).

Medler, J. & Wajant, H. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-2 (TNFR2): An overview of an emerging drug target. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets https://doi.org/10.1080/14728222.2019.1586886 (2019).

Medler, J., Kucka, K. & Wajant, H. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2): An Emerging target in cancer therapy. Cancers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14112603 (2022).

Fiedler, T. et al. Co-modulation of TNFR1 and TNFR2 in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroinflammation https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-023-02784-z (2023).

Fischer, R. et al. TNFR2 promotes Treg-mediated recovery from neuropathic pain across sexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1902091116 (2019).

McCulloch, T. R. et al. Dichotomous outcomes of TNFR1 and TNFR2 signaling in NK cell-mediated immune responses during inflammation. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54232-y (2024).

Li, M., Zhang, X., Bai, X. & Liang, T. Targeting TNFR2: A novel breakthrough in the treatment of cancer. Front. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.862154 (2022).

Patel, J. R. & Brewer, G. J. Age-related changes to tumor necrosis factor receptors affect neuron survival in the presence of beta-amyloid. J. Neurosci. Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.21663 (2008).

Li, L. et al. Targeting TNFR2 for cancer immunotherapy: Recent advances and future directions. J. Transl. Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-05620-x (2024).

Park, M. J. & Choi, K. M. Interplay of skeletal muscle and adipose tissue: Sarcopenic obesity. Metabolism https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2023.155577 (2023).

Donini, L. M. et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria for sarcopenic obesity: ESPEN and EASO consensus statement. Obes. Facts https://doi.org/10.1159/000521241 (2022).

Ma, L. et al. High serum tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 levels are related to risk of low intrinsic capacity in elderly adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1533-y (2021).

Lu, W. H. et al. Plasma inflammation-related biomarkers are associated with intrinsic capacity in community-dwelling older adults. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13163 (2023).

Wilson, D., Jackson, T., Sapey, E. & Lord, J. M. Frailty and sarcopenia: The potential role of an aged immune system. Ageing Res. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2017.01.006 (2017).

Nguyen, A. D. et al. Serum progranulin levels are associated with frailty in middle-aged individuals. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238877 (2020).

Kochlik, B. et al. Frailty is characterized by biomarker patterns reflecting inflammation or muscle catabolism in multi-morbid patients. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13118 (2022).

de Campos, G. C., Lourenço, R. A. & Molina, M. D. C. B. Mortality, sarcopenic obesity, and sarcopenia: Frailty in Brazilian Older People Study—FIBRA—RJ. Rev. Saude Publica https://doi.org/10.11606/S1518-8787.2021055002853 (2021).

Ferriollia, E. et al. Assessment of intrinsic capacity in the Brazilian older population and the psychometric properties of the WHO/ICOPE screening tool: A multicenter cohort study protocol. Geriatr. Gerontol. Aging https://doi.org/10.53886/gga.e0000166_EN (2024).

Westbury, L. D. et al. Relationships between markers of inflammation and muscle mass, strength and function: Findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Calcif. Tissue Int. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-017-0354-4 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the laboratory evaluation team, the professionals from the Health Department and the Basic Health Units of the municipality of Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG APQ-00277-24 e APQ-01328-18), for Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (Universal CNPq-402574/2021-4 e CNPq-151412/2024-3) and the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES PROEXT-PG 88881.926996/2023-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.A.C.T. was responsible to conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; roles/writing—original draft; and writing - review & editing. L.A.S contribution to conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; visualization; and writing—review & editing. H.S.C was responsible for design, interpretation of the study and critical review. J.N.P.N contribution to design, execution, draft, interpretation of the study and critical review. A.A.V with design, execution, interpretation of the study and critical review. N.C.P.A with design, interpretation of the study and critical review. P.H.S.F contributing to design, interpretation of the study and critical review. A.N.P collaborated with conceptualization, data curation; investigation; methodology; project administration; supervision; validation; visualization; roles/writing—original draft; and writing—review & editing. V.A.M with conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; roles/writing—original draft; and writing—review & editing; and ACRL was responsible to conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; roles/writing—original draft; and writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

da Costa Teixeira, L.A., Soares, L.A., Silveira Costa, H. et al. Analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of plasma sTNFr-2 concentrations in identifying sarcopenia in community-dwelling older women. Sci Rep 15, 19545 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95368-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95368-1