Abstract

The CheckMate 649 trial demonstrated the clinical benefit of nivolumab plus chemotherapy in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative advanced gastric cancer. However, the background discrepancy between clinical practice and randomized controlled trials may impact the therapeutic strategy and prognosis of patients. This study aimed to assess the clinical significance of eligibility criteria determined by the CheckMate 649 trial and identify prognostic factors in clinical practice. A total of 160 patients with HER2-negative metastatic gastric cancer who underwent chemotherapy were retrospectively enrolled and classified into two groups based on eligibility criteria. Among the 160 patients, 76 (47.5%) and 84 (52.5%) were included in the eligible and ineligible groups, respectively. The ineligible group had a significantly lower induction of second- and third-line chemotherapy than the eligible group (P = 0.02 and P = 0.02, respectively). The median overall survival in the eligible and ineligible groups was 22.9 and 10.5 months, respectively, with the ineligible group having a significantly poorer prognosis than the eligible group (P < 0.01). Responders to first-line chemotherapy had a better prognosis than non-responders in both groups (P = 0.01 and P < 0.01, respectively). Multivariate analyses identified disease control as an independent prognostic factor in both groups (P < 0.01 and P < 0.01, respectively). Patients with a poor general condition who fulfilled the ineligibility criteria as determined using randomized controlled trials are included in clinical practice, and these criteria are related to tumor response and prognosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ATTRACTION-2 trial demonstrated the clinical utility of nivolumab as third-line chemotherapy for unresectable advanced or recurrent gastric cancer1. Based on this finding, nivolumab was introduced as third-line chemotherapy from September 2017 in Japan2. In contrast, the CheckMate 649 trial indicated that nivolumab plus chemotherapy resulted in superior overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and improved objective response rates compared to chemotherapy alone in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative unresectable or metastatic gastric cancer3,4. Therefore, nivolumab plus chemotherapy was introduced as first-line chemotherapy for HER2-negative advanced gastric cancer from November 2021 in Japan.

Recommended chemotherapy regimens are determined with randomized controlled trials (RCT). Moreover, most RCTs have established eligibility criteria for selecting suitable patients to undergo chemotherapy. The CheckMate 649 trial had the following exclusion criteria: performance status (PS) of 2 or 3, ascites uncontrolled by appropriate interventions, hematopoietic disorders, non-preserved liver or renal function, hypoalbuminemia, and untreated brain metastasis3,4. Even in the Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines, systemic chemotherapy is indicated for patients with a PS of 0–2, preserved major organ function, and no serious comorbidities2. However, in reality, because patients with poor general conditions already exist in clinical practice, it is often challenging to develop a therapeutic strategy for them. Accordingly, in patients with unresectable advanced gastric cancer, a discrepancy in clinicopathological features between clinical practice and RCTs may affect clinical management, including post-progression chemotherapy, tumor response, and prognosis. However, few studies have investigated this issue5,6.

This study aimed to examine the clinicopathological features and therapeutic strategy of patients with HER2-negative advanced gastric cancer who underwent chemotherapy based on the eligibility criteria determined by the CheckMate 649 trial. Moreover, we aimed to identify important factors associated with prognosis in clinical practice.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed 160 patients with HER2-negative metastatic gastric cancer who received chemotherapy at the Kagoshima University Hospital (Kagoshima, Japan) between February 2002 and November 2021. Patients with synchronous or metachronous cancer in other organs or disease recurrence were excluded from this study. All the patients underwent blood examinations, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and computed tomography before chemotherapy. The patients were classified and staged according to the tumor-lymph node-metastasis (TNM) classification for gastric carcinoma7. This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kagoshima University (approval number: 220136) and was conducted per the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of Kagoshima University waived the requirement for written informed consent due to the retrospective observational design, and an opt-out opportunity was provided on the institutional website.

Eligibility criteria determined by the CheckMate 649 trial

The CheckMate 649 trial excluded patients with a PS of 2 or 3, ascites uncontrolled by appropriate interventions, hematopoietic disorder (white blood cell count < 2,000/mm3, absolute neutrophil count < 1,500/mm3, platelet count < 100,000/mm3, or hemoglobin < 9.0 g/dL), non-preserved liver or renal functions (serum aspartate transaminase or alanine aminotransferase levels > 3 times the upper limit of normal [ULN], serum bilirubin level > 1.5 times ULN, serum creatinine level > 1.5 times ULN, or creatinine clearance < 50 mL/min), hypoalbuminemia (serum albumin < 3.0 g/dL), or untreated brain metastasis3. Patients were categorized into eligible and ineligible groups based on the eligibility criteria determined by the CheckMate 649 trial. Patients who met at least one ineligibility criterion were assigned to the ineligible group.

Evaluation of tumor response to chemotherapy

Tumor response was assessed every two or three chemotherapy cycles and determined using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST)8. The tumor response was classified into the following categories: complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD). For this study, patients exhibiting CR or PR and SD or PD were defined as responders and non-responders, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The relationship between eligibility criteria and clinicopathological features, including tumor response and second- or third-line chemotherapy, was evaluated using the Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, or Wilcoxon rank-sum test. OS was defined as the period from the initiation of first-line chemotherapy to death or last follow-up. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated, and prognostic differences were assessed using the log-rank test. Prognostic factors were assessed using univariate and multivariate analyses (Cox proportional hazards regression modeling). All data were analyzed using JMP17 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Evaluation based on eligibility criteria determined by the CheckMate 649 trial

Among the 160 patients, 27 (16.9%), 17 (10.6%), 15 (9.4%), 23 (14.4%), four (2.5%), 34 (21.3%), 25 (15.6%), and one (0.6%) had a PS of 2, a PS of 3, uncontrolled ascites, hematopoietic disorders, non-preserved liver function, non-preserved renal function, hypoalbuminemia, and untreated brain metastasis, respectively. Consequently, 76 (47.5%) and 84 (52.5%) patients were classified into the eligible and ineligible groups, respectively.

Eligibility criteria and clinicopathological features

The median ages of the eligible and ineligible groups were 63 and 72 years, respectively (Table 1). Patients in the ineligible group were significantly older than those in the eligible group (P < 0.01). The ineligible group had a significantly higher PS than the eligible group (P < 0.01). Moreover, the ineligible group had a significantly higher rate of dose reduction than the eligible group in first-line chemotherapy initiation (P = 0.04). Additionally, the ineligible group had a significantly fewer number of administrations than the eligible group in first-line chemotherapy (P < 0.01). Conversion surgery was performed on 29 (38.2%) and 15 (17.9%) patients in the eligible and ineligible groups, respectively (Table 1). Therefore, the eligible group had a significantly higher conversion surgery induction rate than the ineligible group (P < 0.01). No significant relationships between eligibility criteria and other clinicopathological features, such as sex, tumor location, macroscopic type, tumor invasion depth, lymph node metastasis, number of distant metastatic sites, histological type, first-line chemotherapy regimen, and treatment-related adverse events were identified (all P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Eligibility criteria and tumor response to the first-line chemotherapy

Among these patients, 85 had target lesions, according to the RECIST. RECIST demonstrated that disease control was achieved in 33 (80.5%) and 18 (40.9%) patients in the eligible and ineligible groups, respectively (Table 2). Accordingly, the eligibility criteria were significantly correlated with tumor response (P < 0.01).

Eligibility criteria and second-line or third-line chemotherapy

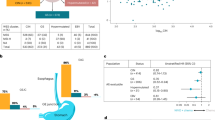

Table 3 shows the first, second, and third-line regimens of chemotherapy in both the eligible and ineligible groups. A total of 60 (79.0%) and 52 (61.9%) patients in eligible and ineligible groups, respectively, underwent second-line chemotherapy (Fig. 1a). Moreover, 39 (51.3%) and 27 (32.1%) patients in the eligible and ineligible groups, respectively, received third-line chemotherapy (Fig. 1b). Consequently, the ineligible group had a significantly lower rate of second-line and third-line chemotherapy than the eligible group (P = 0.02 and P = 0.02, respectively).

Eligibility criteria and prognosis

The median follow-up time was 14.4 months. The number of OS events was 56 and 77 in eligible and ineligible groups, respectively. The median OS of the eligible and ineligible groups was 22.9 and 10.5 months, respectively (Fig. 2). The ineligible group had a significantly shorter prognosis than the eligible group (P < 0.01). No significant prognostic difference based on the first-line regimen of chemotherapy was observed in either group (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Among the 85 patients who had target lesions according to RECIST, patients in each group were classified based on their tumor response to first-line chemotherapy (responders vs. non-responders). The median OS of responders and non-responders in the eligible group was 27.6 and 12.2 months, respectively (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, the median OS of the responders and non-responders in the ineligible group was 19.1 and 5.3 months, respectively (Fig. 4b). Accordingly, a significant prognostic difference between responders and non-responders was observed in both eligible and ineligible groups (P = 0.01 and P < 0.01, respectively).

Multivariate analysis revealed that sex, disease control, and conversion surgery were independent prognostic factors in the eligible group (P = 0.03, P < 0.01, and P < 0.01, respectively) (Table 4). Moreover, multivariate analysis identified PS, disease control, and conversion surgery as independent prognostic factors in the ineligible group (all P < 0.01) (Table 5).

Discussion

This study investigated the background of patients with HER2-negative unresectable or metastatic gastric cancer who fulfilled the ineligibility criteria determined by the CheckMate 649 trial. The following was shown: (1) over half of the patients had at least one ineligibility factor, (2) the induction rate of post-progression chemotherapy was extremely low in the ineligible group, and (3) even in the ineligible group, responders had a favorable prognosis, and disease control was an independent prognostic factor based on multivariate analysis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the prognostic significance of eligibility criteria determined by the CheckMate 649 trial in patients with HER2-negative advanced gastric cancer and demonstrate the importance of tumor response in clinical practice.

The first point to be discussed is the difference in the backgrounds of the populations between clinical practice and RCT. Therefore, we evaluated patients who underwent chemotherapy based on the eligibility criteria determined by the CheckMate 649 trial in this study. Over 50% of patients were ineligible for inclusion in this study. Moreover, a PS of 2 or 3 was observed in 27.5% of the patients, and poor PS was ranked as the most frequent ineligibility factor. Several previous studies have demonstrated poor PS or large amounts of ascites as an important prognostic factor in patients with metastatic gastric cancer9,10,11,12. Ando et al. reviewed the clinicopathological factors in 335 patients with unresectable or recurrent gastric cancer who underwent chemotherapy and classified them into those who met the eligibility criteria for clinical trials and those who did not5. They reported that 199 (59.4%) patients were categorized into the ineligible group5. These findings indicated a significant discrepancy in the clinicopathological properties of patients between clinical practice and RCT. Taken together, it is important to note how to successfully manage patients with poor general conditions in the chemotherapeutic strategy of clinical practice.

Next, we focused on the induction rates of second-line and third-line chemotherapy in both the eligible and ineligible groups. Predictably, the ineligible group had fewer patients who underwent second-line and third-line chemotherapy than did the eligible group. The induction rate of third-line chemotherapy in the ineligible group was 32.1%. Similarly, Ueno et al. reported that the induction rate of third-line chemotherapy was 26.2% in a real-world setting9. These results demonstrate the low induction rate of third-line chemotherapy in clinical practice. Accordingly, when the induction of nivolumab is planned as a third-line regimen, this strategy may result in unused nivolumab due to the low induction of post-progression chemotherapy in clinical practice. Nivolumab is a representative immune checkpoint inhibitor that has demonstrated clinical efficacy for improving prognosis in patients with unresectable or recurrent gastric cancer1,3,4,13,14,15,16. Therefore, early nivolumab induction may be recommended as a chemotherapeutic strategy.

In this study, a close relationship between the eligibility criteria and tumor response was observed, and the ineligible group had a significantly poorer tumor response than the eligible group (P < 0.01). We investigated upfront dose reduction and the number of administrations in the first-line chemotherapy. The eligibility criteria were significantly correlated with upfront dose reduction and the number of administrations in first-line chemotherapy (P < 0.05). Therefore, these results would have affected tumor response to first-line chemotherapy and prognosis between the eligible and ineligible groups. However, among the 44 patients in the ineligible group, 13 demonstrated a tumor response of CR or PR. The response rate in the ineligible group was 29.6%. These findings suggest that we can achieve a promising tumor response even in the ineligible group. Furthermore, the prognosis of responders was significantly better than that of non-responders in both the eligible and ineligible groups. Cox proportional hazards regression modeling demonstrated a hazard ratio of 0.37 and 0.26 between responders and non-responders in the eligible and ineligible groups, respectively. Additionally, multivariate analysis identified disease control as an independent prognostic factor in both ineligible and eligible groups. Consequently, a favorable tumor response leads to prognostic improvement in the eligible and ineligible groups. These findings emphasize the importance of tumor response in the therapeutic strategy of clinical practice. The present study showed that PS was selected as an important prognostic factor in multivariate analysis of the ineligible group (Table 5). Several investigators have demonstrated that better PS is one of favorable factors for survival in patients with metastatic gastric cancer undergoing chemotherapy without immune checkpoint inhibitors17,18. PS could be improved by multidisciplinary interventions including nutritional care and physical exercise19. Accordingly, the effective approach for a recovery of PS might contribute to the improvement of prognosis in patients with unresectable advanced gastric cancer who undergo chemotherapy.

The current study has certain limitations. First, this was a single-center retrospective study with a small sample size (n = 160). Second, chemotherapeutic regimens and dose adjustments were clinically determined based on the registration proposed by the clinical trials, patient conditions, or the physician’s discretion. In particular, the present study did not include patients who used immunotherapy as the first-line treatment. Accordingly, this study provides a first step in assessing the clinical utility of conventional chemotherapy without immune checkpoint inhibitors based on eligibility criteria of the CheckMate 649 trial. However, it is important to assess the clinical utility of immunotherapy based on eligibility criteria of the CheckMate 649 trial in the clinical practice. We therefore hope to explore this key issue in future research. Third, data on relative dose intensity during treatments and severe toxicity of grade 3 or higher was not available. These limitations may have resulted in a bias that could have affected our results. Furthermore, multivariate analyses showed conversion surgery as an independent prognostic factor in both the eligible and ineligible groups (Tables 4 and 5). However, the clinical significance of conversion surgery after chemotherapy remains unclear in patients with advanced gastric cancer2. Further studies are required to confirm our conclusions, including the prognostic impact of conversion surgery.

In conclusion, this study indicates that patients with a poor general condition who fulfilled the ineligibility criteria determined by RCT are included in clinical practice, and these criteria are related to tumor response and prognosis.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as they contain personal patient information, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kang, Y. K. et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 390, 2461–2471 (2017).

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2021. Gastric Cancer. 26, 1–25 (2023). 6th ed.

Janjigian, Y. Y. et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 398, 27–40 (2021).

Janjigian, Y. Y. et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy for advanced gastric, gastroesophageal junction, and esophageal adenocarcinoma: 3-year follow-up of the phase III checkmate 649 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 2012–2020 (2024).

Ando, T. et al. Factors, including clinical trial eligibility, associated with induction of third-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer. Oncology 101, 59–68 (2023).

Satake, S. et al. Clinical significance of eligibility criteria determined by the SPIRITS trial in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Oncology 101, 12–21 (2023).

Amin, M. B. et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual 8th edn (Springer, 2017).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST Guideline, version 1.1. Eur. J. Cancer. 45, 228–247 (2009).

Takahari, D. et al. Determination of prognostic factors in Japanese patients with advanced gastric cancer using the data from a randomized controlled trial, Japan clinical oncology group 9912. Oncologist 19, 358–366 (2014).

Takahari, D., Mizusawa, J., Koizumi, W., Hyodo, I. & Boku, N. Validation of the JCOG prognostic index in advanced gastric cancer using individual patient data from the SPIRITS and G-SOX trials. Gastric Cancer. 20, 757–763 (2017).

Zheng, L. N., Wen, F., Xu, P. & Zhang, S. Prognostic significance of malignant Ascites in gastric cancer patients with peritoneal metastasis: A systemic review and meta-analysis. World J. Clin. Cases. 7, 3247–3258 (2019).

Iwai, N. et al. Prognostic value of moderate or massive Ascites in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Oncol. Lett. 27, 116 (2024).

Ueno, M. et al. Delivery rate of patients with advanced gastric cancer to third-line chemotherapy and those patients’ characteristics: an analysis in real-world setting. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 10, 957–964 (2019).

Kono, K., Nakajima, S. & Mimura, K. Current status of immune checkpoint inhibitors for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 23, 565–578 (2020).

Kang, Y. K. et al. Nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy in patients with HER2-negative, untreated, unresectable advanced or recurrent gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ATTRACTION-4): a randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 23, 234–247 (2022).

Takahari, D. & Nakayama, I. Perioperative immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy for gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancers: a review of current approaches and future perspectives. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 1431–1441 (2023).

Yoshida, M. et al. Long-term survival and prognostic factors in patients with metastatic gastric cancers treated with chemotherapy in the Japan clinical oncology group (JCOG) study. Jpn J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 654–659 (2004).

Lee, J. et al. Prognostic model to predict survival following first-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 18, 886–891 (2007).

Wei, W., Chen, F. & Wang, Y. Effect of multidisciplinary team-style continuity of care and nutritional nursing on lung cancer: randomized study. Future Oncol. 20, 3009–3018 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid (No. 23K08198) for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: TA; Data curation: TA, DM, MS, YH, YT; Formal analysis: TA; Investigation: TA, KS, KB, YK; Visualization: TA, DM; Supervision: TO; Project administration: TO; Writing–original draft preparation: TA; Writing–review and editing: all authors. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

TA received lecture fees from Bristol Myers Squib and Daiichi Sankyo, Japan. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arigami, T., Matsushita, D., Shimonosono, M. et al. Prognostic impact of clinical trial eligibility in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Sci Rep 15, 10961 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95501-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95501-0