Abstract

The elaboration of a new family of purine molecules bearing triazole-acetamide units is presented. The structure assigned to such molecules was verified by various techniques, including FT-IR, NMR (1H/13C), and HRMS analysis. The anticancer activity of the resulting compounds was evaluated in vitro against human lung cancer A549, cervical cancer HeLa, and colorectal cancer HCT116 cell lines. Some of the compounds were much more effective than the standard drug doxorubicin (DXN). Toxicity assessments using a healthy cell line indicated that most compounds displayed some level of toxicity, with only a few exceptions. Notably, compounds 5a, 5b, 5e, 5i, and 5j, unveiled significant cytotoxicity, resulting in notable inhibitory concentrations in cell survival against A549 (IC50 = 4.02 − 15.34 µM), HeLa (6.02–22.12 µM), and HCT116 (6.11 − 22.57 µM) at a concentration of 10 µM. Based on the results, the synthesized compounds 5e, 5a, and 5d were able to inhibit A549 cell line by IC50 of 4.02 ± 0.11, 5.20 ± 0.32, and 12.34 ± 0.25 µM, respectively. Additionally, the molecular docking approach was employed to correlate the in vitro anticancer inhibitory activity well with the in-silico study, and the result obtained corroborated that active analogues established several key interactions at positions Ala561(A), Ile559(A), Gly367(A), Cys513(A), Leu557(A), Arg470(A), Asn469(A), Thr560(A) with the active site of the lung cancer protein (PDB: 1 × 2 J). To further understand, the DFT studies have been explored. The results analysis revealed crucial information about the structure, electronic properties, and reactivity of these triazole scaffolds and identified the best inhibitor, 5e, in line with experimental observation. The experimental results were supported by molecular docking analysis, reinforcing the validity of the results. Extending our exploration, an analysis of the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADME-Tox) profiling confirmed the safe use of these newly synthesized compounds, paving the way for promising applications in the medical field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer causes big changes at the molecular and genomic levels, which cause cells to multiply and divide out of control. This makes more tissue in the affected area of the body1. Cancer cells proliferate uncontrolled without adhering to the regular processes of cell development and death, whereas cells normally expand and subsequently die through the process of apoptosis2,3. Skin (non-melanoma) cancer (1.20 million cases), colon and rectal cancer (1.93 million cases), prostate cancer (1.41 million cases), breast cancer (2.26 million cases), stomach cancer (1.09 million cases), and lung cancer (2.21 million cases) were the most prevalent tumour types4. Cancer is considered a multifactorial disease since it is caused by a combination of determining factors, such as ionizing radiation, viruses, chemicals, pollutants, genetic alterations, and contaminated food5. About 13% of all malignancies are lung cancers, and lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related fatalities globally, accounting for more deaths than colorectal, breast, brain, and prostate cancers combined6,7. According to the American Cancer Society, there were 130,180 lung cancer-related fatalities and 236,740 new cases in the US in 2022. Overall, individuals with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have a dismal prognosis and a low 5-year OS of about 17.4%8. About 85% of instances of lung cancer are NSCLC, making it the most prevalent kind. Global cancer statistics for 2023 predict that there will be 10 million cancer-related deaths and 20 million new instances of the disease9. These medications have different ways of working and are selective for different kinds of cancer, but even minor changes to their chemical makeup could negate their anti-cancer effects10,11,12,13.

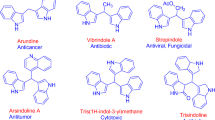

Particularly, nucleosides and modified nucleosides are families of chemicals with intriguing biological properties, such as antiviral, anticancer, and antimetabolic properties14,15,16. The most crucial element in anti-HIV medication combinations is tenofovir; acyclovir is an antiviral medication, and adefovir is used to treat Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections17,18. The most prevalent class of nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds found in nature are purines, including substituted purines and their tautomers19. Analogs of purine nucleosides have been demonstrated to primarily affect DNA synthesis in cells that are actively dividing by inhibiting DNA primase and DNA ligase, as well as by incorporating into and interfering with DNA polymerases and ribonucleotide reductase20. In recent years, nitrogen-containing aromatic heterocyclic compounds—especially imidazoles—have attracted a lot of interest in both industrial and research chemistry, primarily because of their diverse array of pharmacological and biological properties21,22,23. They play a pivotal role in the synthesis of biologically active molecules24, such as anticancer, antiallergic, antirheumatic, anticoagulant, anti-inflammatory, antiprotozoal, antimicrobial, antiaging, anti-tubercular, antidiabetic, antimalarial, antiviral drugs, and enzyme inhibitors25,26,27,28. They also serve as medicinal agents, fungicides, herbicides, and selective regulators of plant growth29. Pyrimidine is the most promising of the heterocycles that have been investigated for their anticancer potential. Since they have antiviral, anticancer, antihypertensive, antimycobacterial, antimicrobial, anti-diabetic, and anti-inflammatory properties, pyrimidines have drawn attention in recent years for their potential to treat a wide range of illnesses30,31,32,33,34.

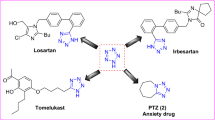

The synthesis and evaluation of a novel class of 1,2,3-triazole-based hybrids and conjugates have demonstrated the potential of 1,2,3-triazoles as “linkers.” They are effective against a wide range of diseases, including cancer, bacteria, TB, viruses, diabetes, malaria, leishmaniasis, and neuroprotection35,36,37. This study’s primary goal was to create a novel series of purine-1,2,3-triazolylacetamide derivatives (5a–5k), describe them, and assess their anticancer properties. In order to gain a better understanding of the electronic and molecular properties of the newly synthesized compounds, a computational analysis was carried out utilizing density functional theory (DFT) calculations. In order to explain the anticancer effect of the targeted compounds by demonstrating the likely binding manner of the molecules with their target protein, molecular docking experiments were also carried out against the best lung cancer that blocked the 1 × 2 J receptor. The compounds were analyzed using virtual screening, which included docking and ADME-Tox profile filters. While ADME-Tox evaluation will provide details on pharmacokinetic and toxicological aspects, docking will show molecular interactions with target proteins. Optimizing the design of physiologically active substances while maintaining their safety is the goal.

Results and discussion

Synthetic chemistry

The synthetic strategy has been developed by clubbing the 2-(4-(((9 H-purin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1 H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)acetyl chloride (3) with the corresponding amines (4a-4k) via HBTU as the coupling agent to furnish 1,2,3-triazole derivatives (5a-5k) as depicted in Scheme 1. This process resulted in the formation of purin-1,2,3-triazole acetamide compounds (5a–5k) by establishing amide bonds through the coupling of the prepared amines. First, we have synthesized 6-(prop-2-yn-1-yloxy)-9 H-purine (2) starting from 9 H-purine-6-ol and propargyl bromide in the presence of KOH, acetone, and using the synthetic method reported in the research article38. Later, utilizing Na-ascorbate and other CuSO4 catalysts at rt in DMF solvent media, we focused on the creation of the formation reaction conditions from 1,4-disubstituted terminal alkyne 2 with 2-azidoacetyl chloride as a model reaction. In order to create the new purine-bearing 1,2,3-triazole with acetamide linker groups in satisfactory yields, the synthesis of the acetamide functionalized 1,2,3-triazole 5a-5k depended on the reactivity of the chloroacetyl of 3 towards the corresponding amine linker in the presence of HATU and DIPEA in DMF, respectively. In order to obtain the light orange layer, the amidation reaction was completed by agitating the resulting mixture for 15 min at room temperature. The mixture was then diluted with water and extracted using DCM.

After evaporation of organic crude material and filtration, the process was purified by flash chromatography; a 60:40 mixture of hexane and ethyl acetate was used as eluent. For amidation products (5a-5k), we just change the reagent quantity following the procedure mentioned above. Following synthesis, all products underwent purification using flash chromatography. The structures of these compounds were determined using analytical methods including 1H and 12C-NMR spectroscopy and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS).

Evidence of NH functionality emerged through a stretching band range of 3356–3348 cm−1. The presence of C = N functionality was established within a stretching band range of 1485–1420 cm−1, while the spectrum’s range of 1380–1340 cm−1 confirmed C–N stretching. Distinctive peaks emerged at 3020–3090 cm−1 and 2835–2873 cm−1, signifying sp2-CH and aliphatic sp3-CH stretching vibrations, respectively. Furthermore, the -C = O stretching peak corresponding to aldehyde was observed at 1730 cm−1, and the -C = O stretching peak corresponding to the amide group appeared at 1680 cm−1. Meanwhile, the C = C, and -COC groups exhibited the stretching vibrations, resonating around 1520–1580 cm−1 and 1165 cm−1, respectively. In the 1H-NMR spectrum, the presence of two singlets of methylene proton intensity at δ 5.65 and 5.59 ppm in the aliphatic region, a sharp singlet at δ 9.85 ppm integrating for one proton corresponding to aldehyde, and a peculiar pattern of phenyl protons in the aromatic region 8.37–7.50 ppm confirm the formation of 5b. In addition, the 1H NMR spectrum of the resulting product displayed a broad singlet at δ 12.81 ppm integrated for the one proton consigned to the purine group and a broad singlet at δ 10.18 ppm integrated for the − CONH proton, whereas another singlet near to δ 7.58 ppm indicated the 1,2,3-triazole proton, respectively13. C-NMR spectrum of compound 5b showed three signals at δ 56.49, and 70.90 due to two methylene carbons of -NCH2 and -OCH2 and ten resonance signals in chemical shift range of 117.23-149.36 ppm due to aromatic carbons and a signal at δ 196.85 ppm due to carbonyl carbon respectively, which clearly indicated the successful condensation of reactants into product 5b. Besides the required number of aromatic signals, the13C-NMR spectrum showed the signals at δ 168.02, 165.33, 152.79, and 152.30 ppm allocated to the amide carbonyl carbon and purine carbons, respectively. The HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C17H14N8O3 is 378.0922 and was observed at 379.1721 for (M + H)+, which also confirmed the product formation. The NMR (1H/13C) and HRMS spectroscopic results obtained for all the final compounds 5a-5k are presented in the supplementary material (Figure S1-S33).

Anticancer activity

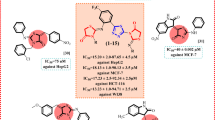

In order to determine whether the type of substituent would impact the selective toxicity for the human lung adenocarcinoma cell line (A549), the human cervical cancer cell line (HeLa), and the human colorectal cancer cell line (HCT116) by MTT assay, a number of structural changes were made to compounds (5a-5k) in relation to the substitution at the acetamide of the 1,2,3-triazole moiety39,40. The well-known chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin is utilized as a standard medicament; it is a reasonable standard cytotoxic agent. A549 (human Lung cancer cell line), HeLa (human cervical cancer cell line), and HCT116 (human colorectal carcinoma cell line) used in the present study were procured from the National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, India. Remarkably, when tested against the A549 cell line, compounds 5a, 5e, 5i, and 5j exhibited the strongest anti-proliferative activity, with IC50 values ranging from 4.02 to 15.34 µM. Additionally, their potency against HeLa and HCT116 cell lines was comparable to that of doxorubicin (IC50 = 6.89 and 7.27 µM, respectively, Table 1), with IC50 values ranging from 6.02 to 8.85 and 6.11 to 22.57 µM, respectively. The chemical 5e, which contains 3-chloro-4-fluorophenyl substituted acetamide, demonstrated high growth anticancer viability properties in the A549 cancer cell line, with IC50 values of 4.02 ± 0.11 µM, as predicted. Excellent cell survival qualities against the A549 cell line were obtained by substituting 5-methylpyridin-3-yl on triazole 5a and 2,4-dimethylphenyl core on triazole 5d (Fig. 1, IC50 of 5.20 ± 0.32 and 12.34 ± 0.25 µM), while 5b, 5k showed moderate anticancer activity against A549 cell line with IC50 values of 13.90 ± 0.34 and 14.20 ± 0.25 µM respectively as compared to the standard doxorubicin (IC50 = 5.86 ± 0.11 µM). Here, the activity was enhanced; this could be because the triazole’s phenyl ring was swapped for the benzyl ring. Compounds 5a, 5e, and 5i demonstrated good anticancer activity against human cervical cancer, their inhibitory concentrations being 7.10 ± 0.19, 8.85 ± 1.09, and 6.02 ± 0.62 µM in relation to the test HeLa cell line (Figs. 2 and 3). The studied cell line for human cervical cancer showed the highest resistance to these substances’ effects. With the exception of compounds 5 g and 5j, which displayed a modest IC50 > 100 µM, none of the investigated compounds had anticancer properties against the HeLa cell line. Samples 5a, 5e, 5f, 5 h, and 5i showed moderate to good anticancer activity against the human colorectal cancer cell line (HCT116); their IC50s were 6.23 ± 0.23, 6.11 ± 0.29, 13.92 ± 0.19, 12.33 ± 0.52, and 7.88 ± 0.60 µM. Compounds 5b and 5j showed a slight anticancer effect against the human colorectal cancer cell line (HCT116) at inhibitory concentrations of 15.60 ± 0.45 and 22.57 ± 0.38 µg/mL, which were lower than the activity of the comparison drug DXN (MIC = 7.27 ± 0.39 µM).

Accordingly, the anticancer potential of the new purine-triazole compounds was examined. Compound 5e, which has -Cl at the p-position and -F at the m-position of the phenyl ring, was found to be significantly active, even more potent than standard DXN. This was because a closer examination of the structure of newly synthesized purine-based triazole-acetamide derivatives and their IC50 values suggested that compounds bearing substituent(s) of accomplishing strong interactions with cancer cells or substituent(s) having strong EW nature, such as -Cl and -F groups at the aryl ring, may aid in better inhibition. Compounds 5c, 5f, and 5i’s inhibitory potential against the human lung adenocarcinoma cell line (A549) was significantly reduced by the attachment of m-tolyl, p-nitrophenyl, and p-hydroxybenzyl. Interestingly, the cell viability profile was further increased by substitution of the -CH3 moiety from its meta-position to the CHO-moiety as in the case of compound 5b. It was noted that the addition of a strong EW substituent, such as -CHO, increased the inhibitory concentration potential; as a result, compound 5b exhibited better anticancer activity than compound 5c, which contains a -CH3 substitution of ED character. The development of the human colorectal cancer cell line (HCT116) was moderately inhibited by electron-donating groups like -OH at the SAR research 1,2,3-triazole with substituted purine (compound 5 h) and (compound 5i). Purines did not exhibit anticancer action against the applicable human colorectal cancer cell line (HCT116) when they were fused to o, p-dimethylphenyl, m-methoxyphenyl, and p-methoxybenzyl with triazolyl acetamide skeletons of 5d, 5 g, and 5k, respectively.

Docking study against lung cancer

Molecular docking is a primary and initial approach for evaluating novel therapeutic agents. This method is a promising and emergent field for the reduction of complexities that occur during the drug discovery process. In the process of drug development, the assessment of lead molecules having drug-likeness and good pharmacological activities is a tedious job. The fundamental concept of rational drug designing is the analysis of ligand-receptor interaction, and such interactions can be predicted by molecular docking and have gained a lot of importance in the area of structure-based drug design and discovery41,42,43,44. The current work demonstrated the in vitro anticancer activity of the synthesized compounds against lung cancer cell lines, and an in-silico evaluation of the synthesized compounds was executed to find out their correlation with the results obtained from in vitro anticancer activity studies. A molecular docking was conducted to investigate the probable binding modes of the most active compounds 5a, 5e, and 5i on the 1 × 2 J protein of the lung cancer cell line (A549), and results are expressed compared to DXN. It was reported that Val561(A), Ile559(A), Gly367(A), Cys513(A), Leu557(A), Arg470(A), Asn469(A), Thr560(A), and Ile421(A) amino acid residues are involved in binding with 1 × 2 J [36, 37]. The formed hydrogen bonds are established within distances of 2.56–3.16 Å, and binding free energies (∆G) revealed were in the range of (‒7.88 to ‒8.96 kcal/mol), with corresponding inhibition constants (Ki) being 2.29 nM to 522.32 µM. As can be seen in Table 2, molecular docking studies of synthesized compounds were performed using Autodock 4.2, and the binding affinities of 5a, 5e, and 5i showed the highest binding interactions in the present study with lung protein.

5a demonstrating energy score at ΔG = − 7.88 kcal/mol and showed an H-bond interaction with Val561(A), Ile559(A), Gly367(A), and Val514(A) at a distance of 2.89, 3.02, 2.98, and 2.56 Å in the human lung complex. In addition, compound 5a showed many van der Waals stackings within the active site of residues Val324(A), Val608(A), Val604(A), Gly605(A), Gly558(A), Gly511(A), Ala510(A), Val512(A), Ala607(A), Ala366(A), Cys368(A), Ala466(A), and Thr560(A). Additionally, one carbon–hydrogen bond was detected between m-methyl pyridine and the residue of Leu557(A) at distance 3.06 Å. The side chain of Ile559(A) was participated in a Pi–donor H-bond interaction with the heterocyclic ring of m-methyl pyridine. Two conventional Pi–alkyl bonds were observed between purine and the residues of Val514(A), Val561(A), other two hydrophobic Pi–alkyl interactions of 1,2,3-triazole and pyridine were detected with the side chains of Val606(A) and Cys513(A). The results obtained from docking imitation are presented in Fig. 4a, b. Similarly, 5e demonstrates highest binding affinity at -8.96 kcal/mol, and purine nucleoside has two H-bonds with the amino acid Val608(A) (distance 2.67 Å, 2.82 Å) respectively, as opposed to standard DXN, which demonstrated binding affinity at -8.25 kcal/mol and has hydrogen bonds with the amino acids Val467(A), Val514(A), Val420(A), His516(A) in lung cancer protein. Additionally, 3-chloro-4-fluorophenyl-acetamide demonstrates good binding interactions with the active pocket of 1 × 2 J via two conventional hydrogen bonds with the residues Val418(A) [2.76 Å], and Gly367(A) [2.52 Å], in addition to Pi-alkyl interaction with Ala366(A). The 1,2,3-triazole fragment interacts through CH-bonding and Pi-alkyl interactions with Gly419(A), Val420(A), and Val467(A) (Fig. 5). The hydrophobic Pi-alkyl and van der Waals interactions of 5e were detected with the side chains of Val369(A), Val608(A), Ala607(A) x 2, Cys368(A), Ala366(A) x 2, Val324(A), Val465(A), Ala466(A), Gly417(A), Thr560(A), Cys513(A), Val512(A), Val606(A), and Gly605(A).

Figure 5 displays the docking results of compound 5i towards the human lung cancer and presents a binding score of -8.73 kcal/mol. On the other hand, purine nucleoside, triazole established a good Pi-alkyl binding interaction Val467(A) x 2, Ala466(A) x 2, Val561(A), Val514(A), and p-hydroxy phenyl ring exhibited two Pi-alkyl stackings Ala607(A), Cys368(A) within the active pocket of 1 × 2 J protein. In addition, 4-hydroxybenzyl-acetamide showed two H-bond possessing’s with the residues Val369(A), and Thr560(A) at a distance 2.64 Å, 2.80 Å respectively, whereas purine motif showed two H-bond interactions with the amino acids Val420(A), Val418(A) at a distance 2.68 Å, 2.91 Å. Additionally, these interactions are stabilized by Pi-sulfur and Pi-donor H-bond interactions with Cys513(A), Val369(A), and van der Waals interactions with Gly419(A), Val608(A), and Ile559(A). The docking of reference ligand DXN within the human lung cancer binding receptor allowing energy score − 8.25 kcal/mol, it was found that 4-amino-5-hydroxy-6-methyltetrahydro-2 H-pyran played a vital role in the binding through a monodentate hydrogen, unfavorable donor-donor bonded interaction with the backbone of the 1 × 2 J protein with amino acids Val420(A), Asp422(A) (distance: 2.51 Å, 2.57 Å). Moreover, the tetrahydrotetracene-5,12-dione ring shared fixation through H-bond interactions with Val467(A) x 2, Val514(A) residues at distance of 2.27 Å, 2.10 Å, and 2.60 Å accordingly. This pyran, and tetrahydrotetracene were stabilized by CH‒bond stackings with Val467(A) and Val514(A), whereas Pi-sigma bonding was shown by tetrahydrotetracene with Val514(A). In addition, it was established hydrophobic interactions with Arg470(A), Asn469(A), Gly419(A), Val418(A), Val465(A), Val512(A), Ile559(A), Thr560(A), Val561(A), Leu515(A), Leu468(A), Gly423(A), and Ile421(A) via van der Waals stackings as shown in Fig. 6a, b. It should be emphasized that this pattern of interactions is visible between the purine, 1,2,3-triazole and substituted phenyl fragments in the synthesised molecules and the amino acids of the lung cancer binding site (1 × 2 J).

Density functional theory analysis

The density functional theory and the quantum expressor calculations have been employed to examine the structures, electronic properties, quantum capacitance, and surface storage charge of graphene-based materials. The top dietary phytochemicals with better docking affinity were used to predict the prominent biological activities, and quantum chemical calculations using density functional theory (DFT)45. All the calculations were carried out using the Gaussian 16 suite of program. Furthermore, the HOMO-LUMO energy gap was determined using DFT calculations at the Lee-Yang-Parr correlation (B3LYP) functional method and the 6–31 g(d) basic level46. In order to understand the nature of stability and reactivity of the studied interaction 5a, 5e, 5i and reference compound DXN respectively, the frontier molecular orbital (FMO) theory which consists of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), energy gap (Egap), and the quantum chemical descriptors was employed for the study (Fig. 7; Table 3)47,48. According to the FMO theory, the highest occupied molecular orbital acts as an electron donor, while the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital acts as an electron acceptor49. As presented in Table 3, the observed HOMO-LUMO energy value of the prepared triazole 5a is -6.19 eV and − 1.07 eV with an energy gap value of -5.12 eV (Fig. 8). After the interaction of 5e, the energy gap value (-6.17 eV and − 1.08 eV) was observed to decrease slightly with value of -5.09 eV. However, an increase in energy gap (-6.22 eV and − 0.45 eV)) was observed for 5i with an energy gap value of -5.77 eV (Fig. 9). These trends of results indicate that 5a and 5i interaction exhibits greater stability as a result of a higher energy gap when compared to the reference compound DXN (Fig. 10). Compounds 5a, 5e, and 5i were discovered to have the highest binding affinity to the target protein based on computational analysis. Based on the aforementioned information, these scaffolds may be proposed as a critical structure for the development and synthesis of new and potent medications.

Drug likeness parameters

ADME-T is a five-letter acronym for Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and toxicity. An analysis was performed on all the potent scaffolds to assess their drug likeness characteristics. This analysis is aimed at verifying the drug’s potency along with examining specific drug-likeness attributes. All the scaffolds studied in this research are conforming to these guidelines, like existing market drugs. These rules include various parameters such as log Kp, Lipinski, Ghose, Veber, Egan, and Muegge, Bioavailability, PAINS, Brenk, and lead likeness. The drug-likeness of the synthesized derivatives was evaluated using the SwissADME online toolkit and ADMETlab3.0 property explorer50,51,52. The analysis was conducted using the SMILES notation of the synthesised compounds and elucidating their drug-likeness attributes. ADME-T properties help us to predict the properties of specific molecules, which show drug-like properties. Adhering to Lipinski’s rule of five, a compound is deemed drug-like if it possesses a molecular weight of 500 Daltons or less, fewer than 5 hydrogen bond donors, a log P value not exceeding 5, and fewer than 10 hydrogen bond acceptors. More than two violations of these criteria may imply potential bioavailability issues. A polar surface area exceeding 140 Å2 often indicates poor cell membrane penetration, while a TPSA value below 140 Å2 suggests superior intestinal absorption. Substances with a TPSA of less than 60 Å2 typically traverse the blood-brain barrier and exhibit favorable bioavailability. The results in Fig. 11 confirm that expect for 5f, all the derivatives conform to Lipinski’s rules. Veber, Ghose, Egan, and Muegge’s rules further support these compounds, indicating that these molecules with ten or fewer rotatable bonds and a TPSA of 140 Å2 or less are considered drug-like53,54.

Permeability, evaluated using the Caco-2 cell system, indicated values < 4 for poor, 4–70 for medium, and > 70 for significant permeability. MDCK cellular arrangement was utilized for quick permeability screening, with values < 25 for minimal, 25–500 for intermediate, and > 500 for significant permeability. Additionally, the percentage of drugs binding to plasma proteins was considered, with values < 90% indicating weak binding and > 90% significant binding. The “BB” symbol denoted blood-brain barrier penetration, where values less than 0.1 indicated poor absorption, 0.1-2.0 signified mild absorption, and greater than 2.0 indicated significant absorption into the CNS55. Regarding crossing the blood-brain barrier in vivo, the compounds showed a range from 0.10 to 2.45, indicating moderate to good penetration ability, facilitating their distribution in vivo. Table 4 provides a comprehensive assessment of the distribution and potential absorption risks associated with a series of novel synthesized purine-1,2,3-triazole acetamide (5a-5k) derivatives. In vitro permeability assessments using MDCK and Caco-2 cells yielded diverse results, with permeability values ranging from 0.01 to 62.81 nm/s and 1.84 to 54.09 nm/s, suggesting these results from poor to medium permeability. Regarding metabolism, the compounds were found to interact differently with CYP1A2, 2C19, 2C9, 2D6, and 3A4 enzymes56. While they were mostly non-inhibitors and non-substrates of CYP2D6, some were substrates of CYP3A4 (5c, 5f, and 5j), implicating potential liver metabolism. In terms of carcinogenicity, most compounds were deemed non-carcinogenic in mice. The risk of hERG and AMES inhibitions, which can lead to cardiac side effects, AMES was found to be high for DXN and moderate for 5a–5k, whereas hERG was found to be low for DXN and high for 5a–5k (Table 4). The results of the ADME revealed six physicochemical properties: lipophilicity, size, polarity, solubility, saturation, and flexibility. Compounds 5a-5k and doxorubicin showed no deviation in all physicochemical properties, while 5e and DXN showed a slight deviation in saturation and polarity, respectively (Fig. 12). In addition, our prepared purine-1,2,3-triazole acetamide (5a-5k) and doxorubicin were good substrates for P-glycoprotein. Furthermore, all these analogues showed high GI absorption as they were located in the boiled egg white, but 5f and DXN showed low GI absorption. Finally, all the compounds are located outside of the boiled egg yolk, so they cannot penetrate the blood–brain barrier (Fig. 13).

Materials and methods

All chemicals [9 H-purin-6-ol (98%), propargyl bromide (97%), 2-azidoacetyl chloride (97%), sodium ascorbate (99%), HATU (98%), and 5-methylpyridin-3-amine (97%)] were procured from Sigma-Aldrich, and Merck and used as they are without any further purification. Analytical grade (AR) solvents and double distilled water were used throughout the biological studies. The1H13, C-NMR data for prepared compounds were recorded on a Varian Unity INOVA500MHz FT NMR spectrometer (Varian, Germany) using CDCl3/DMSO-d6 as solvent (Cambridge Isotopic Labs, USA). The1H and13C-NMR chemical shift values were reported on the δ scale, TMS as an internal standard, and coupling constants (J) are given in Hz. The infrared spectrum for these analogues was obtained from 4000 cm−1 to 500 cm−1 in the Perkin Elmer FT-IR instrument connected with Spectrum v.2 software using a dried potassium bromide pellet as a medium. The instrument is calibrated using polystyrene film 0.038 μm. Electrospray ionization mass spectra (ESI-MS) were recorded on an LCQ Fleet mass spectrometer; Thermo Fisher Instruments Limited US was used for recording mass spectra. Shimadzu UV-1800 UV-vis spectrometer was used for UV absorption (for biological studies). The progress and completion of reactions were checked by TLC on 2 × 5 cm pre-coated silica gel 60 F254 plates of a thickness of 0.25 mm (Merck). The TLCs were visualized under UV 254–366 nm and/or iodine. The anticancer activity of the purine based 1,2,3-triazole compounds and DXN was assessed using the MTT assay. A549 (Human Lung cancer cell line), HeLa (Human cervical cancer cell line), and HCT116 (Human colorectal carcinoma cell line) used in the present study were procured from National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, India.

Synthesis of 6-(prop-2-yn-1-yloxy)-9 H-purine (2)

To a stirred solution of 9 H-purin-6-ol (1) (1.5 g, 10.94 mmol) in acetone (10 mL), 3-bromoprop-1-yne (1.5 g, 13.13 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) in 10 mL of acetone was added dropwise through a dropping funnel to the reaction mass at 10 ˚C for 20 min. Stirred the reaction mass at room temperature for 7 h and monitored the reaction progress by TLC (DCM: MeOH; 9:1). Following the reaction process, the solution was allowed to cool, and then it was acidified using dil. hydrochloric acid. The reaction mass was washed with water (100 mL) and then extraction was done by twice addition of methylene chloride (2 × 50 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulphate and solvent was removed under reduced pressure to obtain the desired product. After the evaporation and filtration process, the product was purified by flash chromatography; a 60:40 mixture of hexane and ethyl acetate was used as eluent (yield 83%; mp. 102 ˚C).

Synthesis of 2-(4-(((9 H-purin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1 H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)acetyl chloride (3)

In a 250 mL round bottom flask, a solution containing 1.3 g of 6-(prop-2-yn-1-yloxy)-9 H-purine (2) (equivalent to 7.42 mmol) dissolved in 15 milliliters of N, N-dimethylformamide was combined with 2-azidoacetyl chloride (1.15 g, 9.65 mmol, 1.3 equiv.) at below rt. Subsequently, 1.32 g of sodium ascorbate (6.68 mmol, 0.9 equiv.) and 1.47 g of copper sulphate (5.94 mmol, 0.8 equiv.) were introduced into the solution at 15 ˚C. The resulting mixture was subjected to rt for a duration of 6 h, and the reaction progress was monitored by TLC (DCM: MeOH; 9:1). After completion of the reaction, it was diluted with deuterated water (100 mL) and ethyl acetate (2 × 50 mL), and the resulting precipitate was collected via filtration, washed with water, and subsequently dried under vacuum conditions. To purify the crude product, it was recrystallized from acetone using decolorizing charcoal. The final yield was 80%, and the product obtained was a pale-yellow hue with a melting point of 108–110 ˚C and an Rf value of 0.6 (MeOH: CHCl3 1:9).

General procedure for the synthesis of 5a-5k

2-(4-(((9 H-purin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1 H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)acetyl chloride (3) (1.2 g, 4.06 mmol) and HATU (1.3 g, 4.06 mmol, 1 equiv.) were dissolved in 15 mL of N, N-dimethylformamide in a 250 mL RBF equipped with a mechanical stirrer. In a separate flask, a solution of 5-methylpyridin-3-amine (4a) (0.62 g, 5.69 mmol, 1.4 equiv.), in 1.04 g of N, N-diisopropylethylamine (8.12 mmol, 2 equiv.) was prepared and was added to the reaction mixture all at once, keeping the temperature below 25 ˚C. The resulting mixture was refluxed for 8 h to complete the amide coupling reaction. The amidation reaction was finished off by stirring the resultant mixture and letting it stand for 15 min at rt, and the resultant mixture was diluted with water (150 mL) and extracted with DCM (2 × 50 mL) to obtain the light orange layer. After evaporation of organic crude material and filtration, the process was purified by flash chromatography; a 60:40 mixture of hexane and ethyl acetate was used as eluent (5a; yield 78%; mp. 169–170 ˚C). For remaining amidation products (5b-5k), we just change the reagent quantity following the procedure mentioned above. Following synthesis, all products underwent purification using flash chromatography.

2-(4-(((9 H-purin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1 H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-(5-methylpyridin-3-yl)acetamide (5a)

Brown solid; yields: 67%, mp: 169–171 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO − d6) δ ppm: 12.35 (s, 1 H, purine-NH), 10.03 (s, 1 H, CONH), 8.61 (s, 1 H, pyridine-H), 8.34 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.25 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.09 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.85 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.75 (s, 1 H, triazole-H), 5.51 (s, 2 H, −NCH2), 4.91 (s, 2 H, −OCH2), 2.77 (s, 3 H, −ArCH3). 12C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm: 167.99, 165.23, 153.08, 150.83, 149.18, 136.50, 130.12, 126.42, 124.61, 123.29, 121.13, 118.38, 117.26, 72.11, 59.48, 20.59. IR (KBr, cm−1): 3413 (NH), 3101 (= CH), 2950 (CH), 1694 (CO), 1560 (C = C), 1464 (CN), 1169 (C–O–C). HRMS: 366.1165 [M + H]+.

2-(4-(((9 H-purin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1 H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-(3-formylphenyl)acetamide (5b)

Light yellow solid; yields: 72%, mp: 172–174 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO − d6) δ ppm: 12.81 (s, 1 H, purine-NH), 10.18 (s, 1 H, CONH), 9.85 (s, 1 H, CHO), 8.37 (s, 1 H, pyridine-H), 8.19 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.04 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.38 (d, 1 H, J = 9.2 Hz, Ar-H), 7.24 (d, 1 H, J = 9.2 Hz, Ar-H), 7.58 (s, 1 H, triazole-H), 7.50 (t, 1 H, J = 9.4 Hz, Ar-H), 5.65 (s, 2 H, −NCH2), 5.59 (s, 2 H, −OCH2). 12C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm: 196.85, 168.02, 165.33, 152.79, 152.30, 149.36, 139.52, 132.72, 129.79, 126.16, 123.01, 121.12, 120.69, 118.26, 117.23, 70.90, 56.49. HRMS: 379.1721 [M + H]+.

2-(4-(((9 H-purin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1 H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-(m-tolyl)acetamide (5c)

Gummy solid; yields: 63%, mp: 152–154 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO − d6) δ ppm: 13.01 (s, 1 H, purine-NH), 10.29 (s, 1 H, CONH), 8.77 (s, 1 H, pyridine-H), 8.60 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.23 (s, 1 H, triazole-H), 8.09 (d, 1 H, J = 9.2 Hz, Ar-H), 7.91 (d, 1 H, J = 9.2 Hz, Ar-H), 7.73 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.69 (t, 1 H, J = 9.4 Hz, Ar-H), 5.50 (s, 2 H, −NCH2), 5.34 (s, 2 H, −OCH2), 2.80 (s, 3 H, ArCH3).

12C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm: 168.03, 165.32, 152.72, 152.33, 149.39, 139.50, 132.72, 129.72, 126.19, 123.06, 121.15, 120.63, 118.25, 117.26, 71.90, 57.49, 21.36. HRMS: 365.1865 [M + H]+.

2-(4-(((9 H-purin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1 H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-(2,4-dimethylphenyl)acetamide (5d)

Gummy solid; yields: 60%, mp: 155–157 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO − d6) δ ppm: 12.91 (s, 1 H, purine-NH), 10.17 (s, 1 H, CONH), 8.52 (s, 1 H, pyridine-H), 7.80 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.53 (s, 1 H, triazole-H), 7.34 (d, 1 H, J = 9.2 Hz, Ar-H), 7.10 (d, 1 H, J = 9.2 Hz, Ar-H), 6.81 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 5.07 (s, 2 H, −NCH2), 4.78 (s, 2 H, −OCH2), 2.20 (s, 3 H, ArCH3), 1.92 (s, 3 H, ArCH3). 12C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm: 167.27, 164.16, 156.84, 153.91, 149.11, 137.88, 137.19, 131.47, 129.06, 125.72, 123.11, 120.38, 119.46, 111.75, 72.63, 61.78, 23.66, 17.39. HRMS: 379.0872 [M + H]+.

2-(4-(((9 H-purin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1 H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-(3-chloro-4-fluorophenyl)acetamide (5e)

Brownish solid; yields: 72%, mp: 160–162 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO − d6) δ ppm: 12.05 (s, 1 H, purine-NH), 9.98 (s, 1 H, CONH), 8.40 (s, 1 H, pyridine-H), 8.12 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.75 (s, 1 H, triazole-H), 7.46 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.17 (d, 1 H, J = 9.2 Hz, Ar-H), 6.98 (t, 1 H, J = 9.4 Hz, Ar-H), 5.17 (s, 2 H, −NCH2), 4.68 (s, 2 H, −OCH2). 12C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm: 165.96, 165.05, 155.90, 151.15, 150.96, 144.45, 135.61, 129.34, 129.32, 126.87, 125.96, 122.64, 120.50, 119.39, 71.18, 62.11. HRMS: 403.1374 [M + H]+.

2-(4-(((9 H-purin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1 H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-(4-nitrophenyl)acetamide (5f)

Yellow solid; yields: 74%, mp: 168–170 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO − d6) δ ppm: 12.82 (s, 1 H, purine-NH), 9.88 (s, 1 H, CONH), 8.55 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.84 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.56 (d, 2 H, J = 9.4 Hz, Ar-H), 7.31 (s, 1 H, triazole-H), 7.10 (d, 2 H, J = 9.4 Hz, Ar-H), 5.07 (s, 2 H, −NCH2), 4.46 (s, 2 H, −OCH2). 12C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm: 168.03, 167.50, 154.82, 153.40, 149.10, 142.45, 139.05, 131.16, 124.82, 123.40, 122.05, 120.16, 112.48, 70.50, 61.34. HRMS: 396.1134 [M + H]+.

2-(4-(((9 H-purin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1 H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-(3-methoxyphenyl)acetamide (5 g)

Gummy solid; yields: 62%, mp: 141–143 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO − d6) δ ppm: 13.05 (s, 1 H, purine-NH), 10.26 (s, 1 H, CONH), 8.90 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.61 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.88 (s, 1 H, triazole-H), 7.52 (d, 1 H, J = 9.2 Hz, Ar-H), 7.28 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.12 (t, 1 H, J = 9.4 Hz, Ar-H), 6.80 (d, 1 H, J = 9.2 Hz, Ar-H), 5.28 (s, 2 H, −NCH2), 4.83 (s, 2 H, −OCH2), 3.50 (s, 3 H, OCH3). 12C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm: 169.01, 167.44, 155.00, 153.61, 144.78, 143.40, 140.35, 139.88, 135.12, 125.61, 121.69, 120.43, 114.81, 110.92, 72.41, 61.67, 54.42. HRMS: 381.1741 [M + H]+.

2-(4-(((9 H-purin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1 H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)acetamide (5 h)

White solid; yields: 71%, mp: 187–189 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO − d6) δ ppm: 12.33 (s, 1 H, purine-NH), 10.42 (s, 1 H, CONH), 9.94 (s, 1 H, OH), 8.58 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.37 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.78 (s, 1 H, triazole-H), 7.35 (d, 2 H, J = 9.4 Hz, Ar-H), 7.10 (d, 2 H, J = 9.4 Hz, Ar-H), 5.69 (s, 2 H, −NCH2), 5.25 (s, 2 H, −OCH2). 12C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm: 167.67, 167.28, 157.34, 155.41, 153.59, 143.41, 140.57, 130.06, 124.61, 121.36, 120.20, 117.28, 67.20, 61.79. HRMS: 367.1551 [M + H]+.

2-(4-(((9 H-purin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1 H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-(4-hydroxybenzyl)acetamide (5i)

White solid; yields: 68%, mp: 218–220 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO − d6) δ ppm: 12.85 (s, 1 H, purine-NH), 10.71 (s, 1 H, CONH), 10.09 (s, 1 H, OH), 8.55 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.38 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.90 (s, 1 H, triazole-H), 7.64 (d, 2 H, J = 9.4 Hz, Ar-H), 7.35 (d, 2 H, J = 9.4 Hz, Ar-H), 5.58 (s, 2 H, −NCH2), 5.01 (s, 2 H, −OCH2), 4.28 (s, 2 H, −NCH2). 12C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm: 168.42, 165.87, 156.61, 153.22, 149.83, 142.81, 131.55, 128.91, 127.63, 124.77, 122.06, 120.14, 72.61, 61.59, 44.05. HRMS: 381.1456 [M + H]+.

2-(4-(((9 H-purin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1 H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-(4-chlorobenzyl)acetamide (5j).

White solid; yields: 78%, mp: 175–177 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO − d6) δ ppm: 12.55 (s, 1 H, purine-NH), 10.83 (s, 1 H, CONH), 8.53 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.34 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.59 (s, 1 H, triazole-H), 7.39 (d, 2 H, J = 9.4 Hz, Ar-H), 6.91 (d, 2 H, J = 9.4 Hz, Ar-H), 5.18 (s, 2 H, −NCH2), 4.84 (s, 2 H, −OCH2), 4.35 (s, 2 H, −NCH2). 1C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm: 169.56, 167.04, 159.26, 148.33, 145.17, 140.24, 137.17, 134.36, 130.64, 128.78, 127.27, 115.85, 71.31, 61.66, 44.47. HRMS: 399.1806 [M + H]+, 400.1632 [M + 2 H]+.

2-(4-(((9 H-purin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1 H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-(4-methoxybenzyl)acetamide (5k).

Light Brown solid; yields: 66%, mp: 170–172 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO − d6) δ ppm: 12.35 (s, 1 H, purine-NH), 8.78 (s, 1 H, CONH), 8.50 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.25 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.52 (s, 1 H, triazole-H), 7.24 (d, 2 H, J = 9.4 Hz, Ar-H), 6.98 (d, 2 H, J = 9.4 Hz, Ar-H), 5.44 (s, 2 H, −NCH2), 4.86 (s, 2 H, −OCH2), 4.47 (s, 2 H, −NCH2), 3.70 (s, 3 H, −OCH3). 12C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm: 169.37, 166.96, 160.33, 155.64, 151.91, 140.20, 139.38, 131.96, 124.17, 121.55, 120.49, 114.92, 70.16, 61.70, 56.84, 42.48. HRMS: 395.0968 [M + H]+. You will find general experimental details (biological evaluation, docking research) and characterization data of all the final synthesised purine scaffolds along with copies of 1H-NMR, 12C-NMR, and mass spectra (See supporting information (Fig. S1-S33)).

Conclusion

In this paper, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of the design, synthesis, characterization, anticancer properties, and in silico analysis of novel purine-1,2,3-triazole hybrid conjugates. These compounds were prepared by combining 2-(4-(((9 H-purin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)acetyl chloride with corresponding amines having diverse substituents. The anticancer efficacy of these compounds was evaluated in vitro against three important cancer cell lines, lung cancer (A549), cervical cancer (HeLa), and colorectal cancer (HCT116) with doxorubicin used as a reference drug. Among the compounds tested, 5e showed the highest inhibitory potency against A549 (IC50 = 4.02 ± 0.11 µM), while 5i, and 5a exhibited significant inhibitory effects on HeLa (IC50 = 6.02 ± 0.62 µM) and HCT116 (IC50 = 6.23 ± 0.23 µM) cell growth, with their activities surpassing that of DXN. Furthermore, molecular modelling studies have spotlighted the anchoring role of 1,2,3-triazole substituted purine moiety in H-bonding and hydrophobic interaction with the key amino acid residues. Therefore, these results can provide promising starting points for further development of best anti-cancer agents. Furthermore, in-silico pharmacokinetic and physiochemical profiling of the compounds showed that most adhered to minimal toxicity, and significant inhibitory potential for CYP enzymes, and Lipinski’s rule of five (RO5). Additionally, density functional theory calculations at the B3LYP/6–31 g(d) level in the gas phase were employed to analyze atom charges, EHOMO–ELUMO, electrostatic potential, and other parameters of the triazoles, providing insights to support and elucidate the underlying mechanisms. After careful examination of the results, it is possible to draw the conclusion that these molecules serve as lead molecules for additional synthetic and biological analysis. These synthetic methodologies provide a controlled, modular, and facile access to purine heterocyclic scaffolds with high efficiency, broad substrate scope, and excellent functional group compatibility.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Jafari, A., Babajani, R., Sarrami, F. M., Yazdani, M. & Rezaei, T. Clinical applications and anticancer effects of antimicrobial peptides: from bench to bedside. Front. Oncol. 12, 819563 (2022).

Saxena, M., van der Burg, S. H., Melief, C. J. M. & Bhardwaj, N. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 21, 360–378 (2021).

Siegel, R. L., Giaquinto, A. N. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 12–49 (2024).

Raj Kumar, C. et al. Current research status of anti-cancer peptides: mechanism of action, production, and clinical applications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 164, 114996 (2023).

Graziano, G. et al. Multicomponent Reaction-Assisted drug discovery: A Time-and Cost-Effective green approach speeding up identification and optimization of anticancer drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 6581 (2023).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer Stat. CA 70:7–30 (2020).

Alam, A. et al. Flurbiprofen clubbed Schiff’s base derivatives as potent anticancer agents: in vitro and in Silico approach towards breast cancer. J. Mol. Struct. 1321, 139743 (2025).

Majeed, U., Manochakian, R., Zhao, Y. & Lou, Y. Targeted therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: current advances and future trends. J. Hematol. Oncol. 14, 108 (2021).

Uttpal, A. et al. Cancer chemotherapy and beyond: current status, drug candidates, associated risks and progress in targeted therapeutics. Genes Dis. 10, 1367–1401 (2023).

Uttpal, A. et al. Emerging connectivity of programmed cell death pathways and its physiological implications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 678–695 (2020).

Chaudhary, A., Kalra, R. S. & Malik, V. 2,3-dihydro-3β-methoxy withaferin-A lacks anti-metastasis potency: bioinformatics and experimental evidences. Sci. Rep. 9, 17344 (2019).

Alam, A. et al. Synthesis of novel (S)-flurbiprofen-based esters for cancer treatment by targeting thymidine phosphorylase via biomolecular approaches. J. Mol. Struct. 1316, 138970 (2024).

Samiullah, A. et al. Ketorolac-based ester derivatives as promising hits for malignant glioma: synthesis, brain cancer activity, molecular docking, dynamic simulation and DFT investigation. J. Mol. Struct. 1326, 141128 (2025).

De Clercq, E. Highlights in the discovery of antiviral drugs: a personal retrospective. J. Med. Chem. 53, 1438–1450 (2010).

Shankaraiah, M., Naveen, P., Tejeswara Rao, A. & Kalyani Ch, Jaya Shree, A. Synthesis, characterization and biological evaluation of purine nucleoside analogues. Tetrahedron Lett. 58 (44), 4166–4168 (2017).

Parker, W. B. Enzymology of purine and pyrimidine antimetabolites used in the treatment of cancer. Chem. Rev. 109, 2880–2893 (2009).

Matsuda, A. & Sasaki, T. Antitumor activity of sugar-modified cytosine nucleosides. Cancer Sci. 95, 105–111 (2004).

Mahmoud, S., Hasabelnaby, S., Hammad, S. F. & Sakr, T. M. Antiviral nucleoside and nucleotide analogs: a review. J. Adv. Pharm. Res. 2, 73–88 (2018).

Rosemeyer, H. The chemodiversity of purine as a constituent of natural products. Chem. Biodivers. 1 (3), 361–401 (2004).

Dinesh, S., Shikha, G., Bhavana, G., Nidhi, S. & Dileep, S. Biological activities of purine analogs. J. Pharm. Sci. Innov. 1 (2), 29–34 (2012).

Frank, C. L. et al. Oxalyl boronates enable modular synthesis of bioactive imidazoles. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 6264–6267 (2017).

Zainab, F. et al. Synthesis, anticancer, α-glucosidase inhibition, molecular Docking and dynamics studies of hydrazone-Schiff bases bearing polyhydroquinoline scaffold: in vitro and in Silico approaches. J. Mol. Struct. 1321, 139699 (2025).

Ayaz, M. et al. Biooriented synthesis of Ibuprofen-Clubbed novel Bis-Schiff base derivatives as potential hits for malignant glioma: In vitro anticancer activity and In Silico approach. ACS Omega. 51, 49228–49243 (2023).

Delia, H. R., Víctor, E. T. H., Oscar, G-B., Elizabeth, M. M. L. & Esmeralda, S. Synthesis of imidazole derivatives and their biological activities. J. Chem. Bio. 2, 45–83 (2014).

Ling, Z., Xin, M. P., Guri, L. V. D., Rong, X. G. & Cheng, H. Z. Comprehensive review in current developments of imidazole-based medicinal chemistry. Med. Res. Rev. 34, 340–437 (2013).

alman, A. S., Abdel-Aziem, A. & Alkubbat, M. J. Design, synthesis of some new thio-substituted imidazole and their biological activity. Am. J. Org. Chem. 5, 57–72 (2015).

Zala, S. P., Badmanaban, R., Sen, D. J. & Patel, C. N. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 2,4,5-triphenyl-1H-imidazole-1-yl derivatives. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2 (7), 22 (2012).

Romero, D. H., Heredia, V. E. T., García-Barradas, O., López, M. E. M. & Pavón, E. S. Synthesis of imidazole derivatives and their biological activities. J. Chem. Biochem. 2 (2), 45–83 (2014).

Alzhrani, Z. M., Alam, M. M. & Nazreen, S. Recent advancements on benzimidazole: A versatile scaffold in medicinal chemistry. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 22, 365–386 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. 2-Arylthio-5-iodo pyrimidine derivatives as Non-nucleoside HBV polymerase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 26, 1573–1578 (2018).

Perlíková, P. & Hocek, M. Pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (7-deazapurine) as a privileged scaffold in design of antitumor and antiviral nucleosides. Med. Res. Rev. 37, 1429–1460 (2017).

Ismail, M., El-Sayed, N., Rateb, H., Ellithey, M. & Ammar, Y. Synthesis and evaluation of some 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydropyrimidine-2-Thione and condensed pyrimidine derivatives as potential antihypertensive agents. Arzneimittelforschung 56, 322–327 (2006).

Khandazhinskaya, A. et al. Novel 5′-Norcarbocyclic pyrimidine derivatives as antibacterial agents. Molecules 23, 3069–3087 (2018).

Fang, Y. et al. Design and synthesis of novel Pyrimido[5,4-d]pyrimidine derivatives as GPR119 agonist for treatment of type 2 diabetes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 26, 4080–4087 (2018).

Bozorov, K., Zhao, J. & Aisa, H. A. 1,2,3-Triazole-Containing hybrids as leads in medicinal chemistry: A recent overview. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 27, 3511–3531 (2019).

Basireddy, A., Basireddy, S., Allaka, T., Afzal, M. & PVVN Kishore New Tetrazole-Annulated Pyrazolyl-Pyrimidine derivatives as antimycobacterial targets: design, synthesis, molecular docking, and ADME profiling. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 94 (8), 2008–2017 (2024).

Rani, S., Teotia, S. & Nain, S. Recent advancements and biological activities of Triazole derivatives: a short review. Pharm. Chem. J. 57, 1909–1917 (2024).

Gogisetti, G. et al. Quinolone tethered 1,2,3-Triazole conjugates: design, synthesis, and molecular Docking studies of new heterocycles as potent antimicrobial agents. Russ J. Gen. Chem. 93, S978–S992 (2023).

Othman, D. I. A., Hamdi, A., Tawfik, S. S., Elgazar, A. A. & Mostafa, A. S. Identification of new benzimidazole-triazole hybrids as anticancer agents: Multi-target recognition, in vitro and in Silico studies. J. Enzym Inhib. Med. Chem. 38, 2166037 (2023).

Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 65, 55–63 (1983).

Laskowski, R. A., Jabłońska, J., Pravda, L., Vařeková, R. S. & Thornton, J. M. PDBsum: structural summaries of PDB entries. Protein Sci. 27 (1), 129–134 (2018).

O’Boyle, N. M. et al. Open babel: an open chemical toolbox. J. Chem. Inf. 3, 33 (2011).

Morris, G. M. et al. Autodock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated Docking with selective receptor flexiblity. J. Comput. Chem. 16, 2785–2791 (2009).

Sudhakar Reddy, B. et al. Design, synthesis and in Silico molecular Docking evaluation of novel 1,2,3-triazole derivatives as potent antimicrobial agents. Heliyon 10 (7), e27773 (2024).

Vidya Sagar Reddy, A. et al. Novel 1,2,3-triazole derivatives containing benzoxazinone scaffold: synthesis, Docking study, DFT analysis and biological evaluation. Results Chem. 11, 101800 (2024).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate Ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Bava Bohurudeen, S. Z. et al. Novel benzothiophene–tethered 1,3,4–oxadiazoles as potent antimicrobial targets: design, synthesis, biological evaluation, DFT exploration and in Silico Docking study. J. Mol. Struct. 1322, 140251 (2025).

Miar, M., Shiroudi, A., Pourshamsian, K., Oliaey, A. R. & Hatamjafari, F. Theoretical investigations on the HOMO–LUMO gap and global reactivity descriptor studies, natural bond orbital, and nucleus-independent chemical shifts analyses of 3-phenylbenzo[d]thiazole-2(3H)-imine and its para-substituted derivatives: solvent and substituent effects. J. Chem. Res. 45, 147–158 (2021).

Olowosoke, C. B. et al. Multi-regulator of EZH2-PPARs therapeutic targets: a hallmark for prospective restoration of pancreatic insulin production and cancer dysregulation. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 195, 7520–7552 (2023).

Ye, N., Yang, Z. & Liu, Y. Applications of density functional theory in COVID-19 drug modeling. Drug Discov Today. 27, 1411–1419 (2022).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. Sci. Rep. 7:42717–42729. (2017).

Alegaon, S. G. et al. Synthesis, molecular Docking and ADME studies of thiazolethiazolidinedione hybrids as antimicrobial agents. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 40 (14), 6211–6227 (2022).

Ranade, S. D. et al. Design, synthesis, molecular dynamic simulation, DFT analysis, computational Pharmacology and decoding the antidiabetic molecular mechanism of sulphonamide-thiazolidin-4-one hybrids. J. Mol. Struct. 1311, 138359 (2024).

Lipinski, C. A., Lombardo, F., Dominy, B. W. & Feeney, P. J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 46, 3–25 (2001).

Nam, Q. H. D. et al. Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular modeling studies of 1-Aryl-1H-pyrazole-Fused Curcumin analogues as anticancer agents. ACS Omega. 7, 33963–33984 (2022).

Kakakhan, C. et al. Exploration of 1,2,3-triazole linked benzene sulfonamide derivatives as isoform selective inhibitors of human carbonic anhydrase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 77, 117111 (2023).

Acknowledgements

One of the Author (KMS) is thankful to Reva University for providing required facilities for completion of the research work. The authors extend their appreciation to Ongoing Research Funding Program, (ORF-2025-728), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for financial assistance.

Funding

This work is funded by Researchers Supporting Project number (ORF-2025-728), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KM. Shaik, K. Pandurangan, A. Tejeswara Rao: selected the literature data on the review topic, performed the experiments, supervision and wrote the original paper. Mohammad Z. Ahmed, Seshadri Nalla, Srinivas Ganta and PVVN Kishore: Biological experiments and review the paper. S. Venkatesan: performed the docking, DFT experiments and review the paper; All authors participated in the manuscript preparation and discussions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

You probably are aware that the present manuscript was transferred from the Molecular Diversity (Submission ID 70b55640-d884-4976-aa7f-d92313db7b08) as it fits better to your Journal. For this work, we just need a regular subscription, we don’t need to open access option. We like this journal very much and the scientific works published in it are very good because I am also a reviewer in this Journal. I have requested letter to editorial board at this time of transfer of my submission. In that respect we would like to request you to please consider waiving the processing fee if the article is accepted. During the transfer process, nothing was mentioned regarding article processing charge for your open access Journal. While we really want this paper published in your journal as we now also strongly feel that it is most suitable for that, it is not possible for us to pay the fee presently. In that respect we would like to request you to please consider waiving the processing fee if the article is accepted. Unfortunately, despite best efforts from our side, we are unable to find any alternative solutions to this presently. However, we may also be interested to hear from you regarding other available options, if any. Hope that you will consider our request.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shaik, K.M., Pandurangan, K., Allaka, T.R. et al. Novel purine-linked 1,2,3-triazole derivatives as effective anticancer agents: design, synthesis, docking, DFT, and ADME-T investigations. Sci Rep 15, 26853 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95669-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95669-5